Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. BMI Calculation

2.4. Fat Mass

2.5. Nutritional Behavior

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Anthropometric Measurements

3.2.1. Anthropometric Characteristics of Children at Baseline and Follow-Up

3.3. Nutritional Bahavior

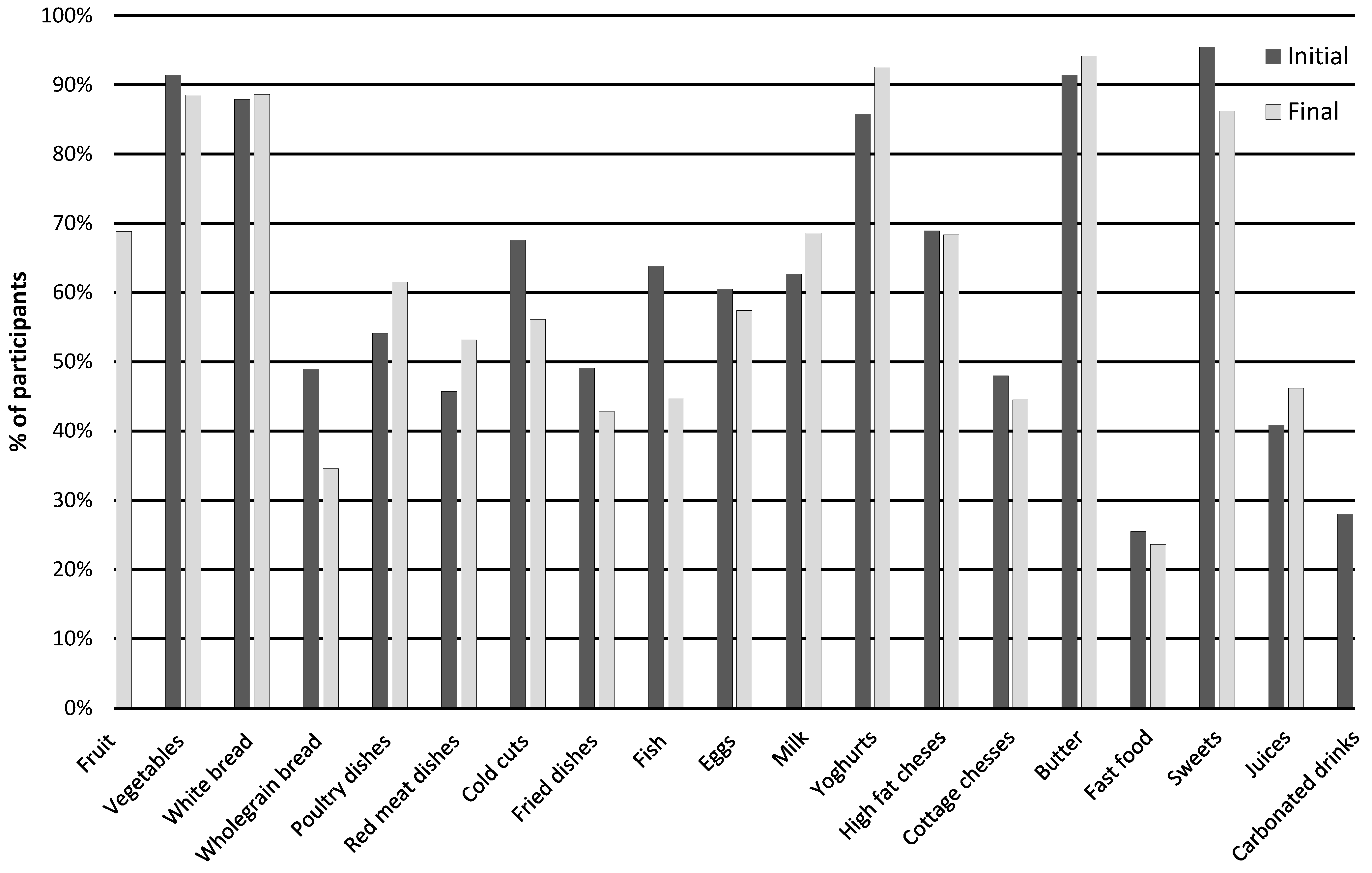

3.3.1. Baseline

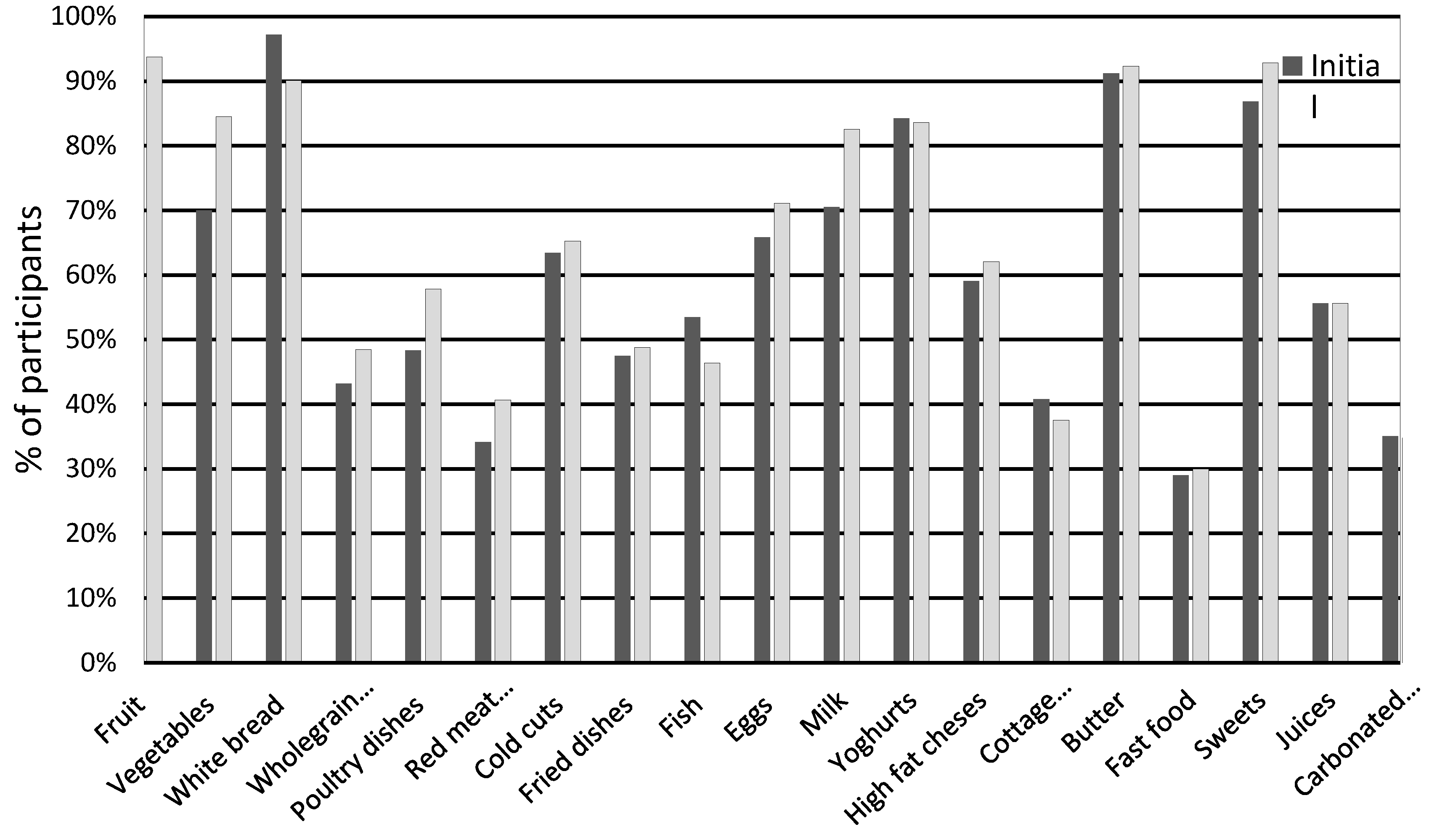

3.3.2. Final

3.3.3. Changes in Nutritional Behavior

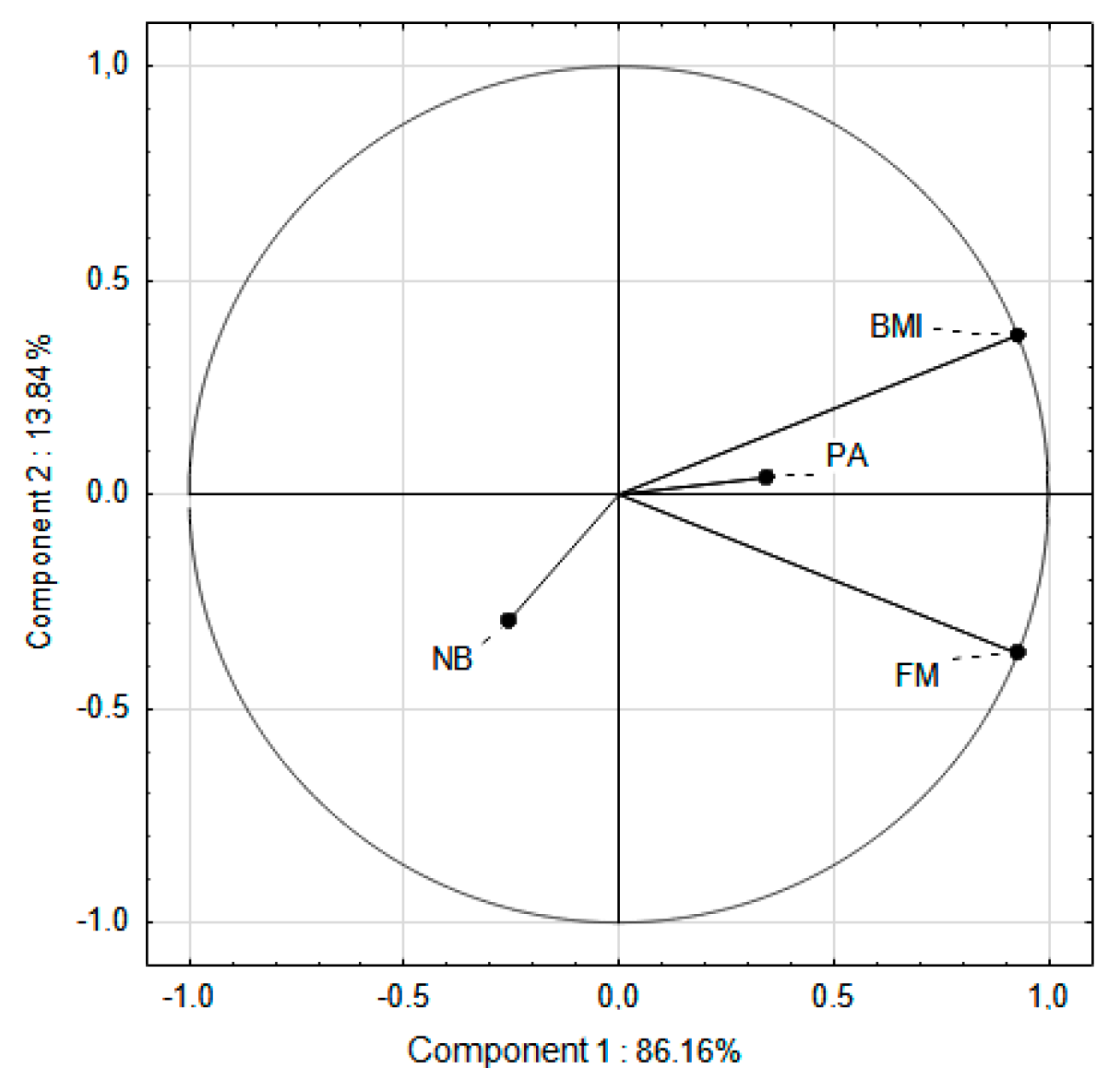

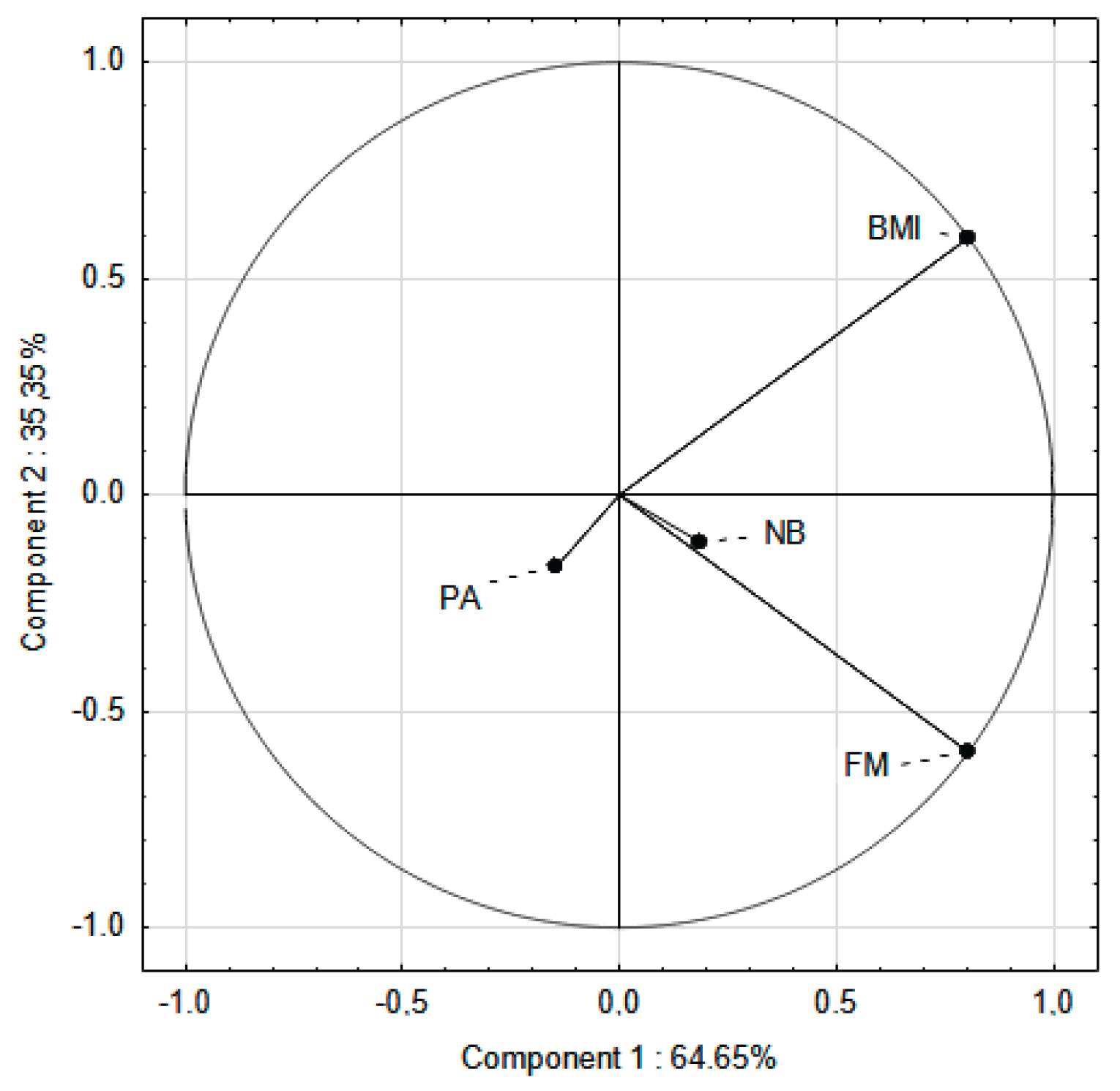

3.4. PCA Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Increased PA on BMI and FM

4.2. The Impact of Increased PA at School on Reducing Body Fat

4.3. The Impact of Increased PA at School on Nutritional Behawior

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| EPA | Elevated Physical Activity group |

| FM | Fat Mass |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PE | Physical Education |

| PF | Physical Fitness |

| SPA | Standard Physical Activity group |

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020.

- Wąsacz, M.; Sarzyńska, I.; Ochojska, D.; Błajda, J.; Bartkowska, O.; Brydak, K.; Stańczyk, S.; Bator, M.; Kopańska, M. Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblacińska, A. Rozwój fizyczny i samoocena masy ciała. In Pupils’ Health in 2018 against the New HBSC Research Model; Mazur, J., Małkowska-Szkutnik, A., Eds.; Instytut Matki i Dziecka: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, M.; Charzewska, J.; Wolnicka, K.; Wajszczyk, B.; Chwojnowska, Z.; Taraszewska, A.; Jaczewska-Schuetz, J. Nutritional status of children and adolescents-preliminary results the programme KIK/34 “Preventing overweight and obesity” in Swiss-Polish Cooperation Programme. Polish J. Human. Nutr. 2016, 43, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Oblacińska, A.; Stalmach, M. Nadwaga i Otyłość u Polskich 8-Latków w świetle Uwarunkowań Biologicznych, Behawioralnych i Społecznych. Raport z Międzynarodowych Badań WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). Warszawa. 2017. Available online: http://www.imid.med.pl/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/country/poland-173/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- World Obesity. Global atlas on childhood obesity. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/membersarea/global-atlas-on-childhood-obesity (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Ngouo, A.T.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tianyi, F.L.; Foka, A.J.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; et al. Global, Regional, and Country Estimates of Metabolic Syndrome Burden in Children and Adolescents in 2020: A Systematic Review and Modelling Analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2022, 6, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.; Jin, M.; Mao, W.; Zhu, G.; Wang, D.; Liang, J.; Shen, B.; et al. The Associations of Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and Lifestyle with the Risk of Developing Hyperuricaemia in Adolescents. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2024, 24, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprio, S.; Santoro, N.; Weiss, R. Childhood Obesity and the Associated Rise in Cardiometabolic Complications. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettlaff-Dunowska, M.; Brzeziński, M.; Zagierska, A.; Borkowska, A.; Zagierski, M.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Changes in Body Composition and Physical Performance in Children with Excessive Body Weight Participating in an Integrated Weight-Loss Programme. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, W.; Ługowska, K. The Effectiveness of Physical Activity Intervention at School on BMI and Body Composition in Overweight Children: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity Among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1. 6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzęk, A.; Sołtys, J.; Gallert-Kopyto, W.; Gwizdek, K.; Plinta, R. Body Posture in Children with Obesity—The Relationship to Physical Activity (PA) Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gil, J.F.; Garcia-Hermoso, A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V.; Kales, S.N. Mediterranean Diet-Based Interventions to Improve Anthropometric and Obesity Indicators in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lacoba, R.; Pardo-Garcia, I.; Amo-Saus, E.; Escribano-Sotos, F. Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: A systematic meta-review. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, S.G.; Herrera Fernández, N.; Rodríguez Hernández, C.; Nissensohn, M.; Román-Viñas, B.; Serra-Majem, L. KIDMED test; prevalence of low adherence to the Mediterranean diet in children and young; a systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 2390–2399. [Google Scholar]

- National Center of Nutrition Education. Healthy Eating Plate. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- FoodandAgriculture Organization of the United Nations. Influencing Food Environments for Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/1c4161e0-8858-4183-b39f-4c76cba27304/content (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Malczyk, Ż.; Pasztak-Opiłka, A.; Zachurzok, A. Different Eating Habits Are Observed in Overweight and Obese Children Than in Normal-Weight Peers. Children (Basel). 2024, 11, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioxari, A.; Amerikanou, C.; Peraki, S.; Kaliora, A.C.; Skouroliakou, M. Eating Behavior and Factors of Metabolic Health in Primary Schoolchildren: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greek Children. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.; Petrou, I.; Manou, M.; Tragomalou, A.; Ramouzi, E.; Vourdoumpa, A.; Genitsaridi, S.-M.; Kyrkili, A.; Diou, C.; Papadopoulou, M.; et al. Dietary and Physical Activity Habits of Children and Adolescents before and after the Implementation of a Personalized, Intervention Program for the Management of Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. The Impact of Physical Activity at School on Children’s Body Mass during 2 Years of Observation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanowski, W.; Ługowska, K.; Trafialek, J. The Impact of Physical Activity at School on Eating Behaviour and Leisure Time of Early Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. Increasing Physical Activity at School Improves Physical Fitness of Early Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aychiluhm, S.B.; Mondal, U.K.; Isaac, V.; Ross, A.G.; Ahmed, K.Y. Interventions for childhood central obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e254331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivel, D.; Tremblay, M.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Fogelholm, M.; Hu, G.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; Olds, T.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Standage, M.; et al. Associations between meeting combinations of 24-hour movement recommendations and dietary patterns of children: A 12-country study. Prev. Med. 2019, 118, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Diamantis, D.V.; Notara, V.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Extracurricular sports participation and sedentary behavior in association with dietary habits and obesity risk in children and adolescents and the role of family structure: A literature review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, T.F.; Stovitz, S.D.; Thomas, M.; LaVoi, N.M.; Bauer, K.W.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Do youth sports prevent pediatric obesity? A systematic review and commentary. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2011, 10, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisinskiene, A.; Lochbaum, M. The Coach-Athlete-Parent Relationship: The Importance of the Sex, Sport Type, and Family Composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułaga, Z.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Góźdź, M.; Wojtyło, M.; Świąder, A.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Litwin, M. Polish 2012 growth references for preschool children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Kułaga, Z.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Góźdź, M; Wojtyło, M.; Świąder-Leśniak, A.; Litwin, M.; Grupa Badaczy OLAF i OLA. Height, weight and body mass index references for growth and nutritional status assessment in children and adolescents 3-18 year of age. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2013, 1, 11–12.

- Kułaga, Z.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Wojtyło, M.; Góźdź, M; Świąder-Leśniak, A.; Litwin, M. Siatki centylowe dla oceny wzrastania i stanu odżywienia polskich dzieci i młodzieży od urodzenia do 18 roku życia. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2015, 12, 119–135.

- McCarthy, H.D.; Cole, T.J.; Fry, T.; Jebb, S.A.; Prentice, A.M. Body fat reference curves for children. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ługowska, K.; Krzęcio-Nieczyporuk, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Kolanowski, W. Changes in BMI and Fat Mass and Nutritional Behaviors in Children Between 10 and 14 Years of Age. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gawęcki, J.; Wądołowska, L.; Czarnocińska, J.; Galiński, G.; Kołłajtis-Dołowy, A.; Roszkowski, W.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Stasiewicz, B. Kwestionariusz do Badania Poglądów i Zwyczajów Żywieniowych dla Osób w Wieku od 16 do 65 lat. Polish Academy of Nciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2020, 22–34.

- Orsso, C.E.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Maisch, M.J.; Haqq, A.M.; Prado, C.M. Using bioelectrical impedance analysis in children and adolescents: Pressing issues. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Bull World Health Organ. 2013, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Marfell-Jones, M.; Old, T.; Steward, A.; Carter, J.E.L. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment; ISAK: Palmerston North, New Zeland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tanita SC-240MA Instruction Manual. Tanita User Manual SC 240 MA. Available online: https://www.manualslib.com/manual/1065295/Tanita-Sc-240ma.html (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- McCarthy, H.D.; Cole, T.J.; Fry, T.; Jebb, S.A.; Prentice, A.M. Body fat reference curves for children. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2013, 23, 143–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, H.S.; Şahin, F.N.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P.; Bianco, A. School-based intervention programs for preventing obesity and promoting physical activity and fitness: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, H.; Chen, S.; Ma, J.; Kim, H. The Association of Body Mass Index and Fat Mass with Health-Related Physical Fitness among Chinese Schoolchildren: A Study Using a Predictive Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, C.; Cherouveim, E.D.; Skouras, A.Z.; Antonakis-Karamintzas, D.; Czvekus, C.; Halvatsiotis, P.; Savvidou, O.; Koulouvaris, P. The Impact of Obesity on the Fitness Performance of School-Aged Children Living in Rural Areas-The West Attica Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzewska, J.; Pastuszak, A.; Lewandowska, J.; Piechaczek, H.; Kęsicka, E. Relationship between physical activity and obesity in adolescents. In: Charzewska, M.; Bregman, P.; Koczanowski, K.; Piechaczek, H.; editors. Obesity as an Epidemic of the 21st Century. PAN; Warszawa, Polan: 2006. pp. 74–81. (In Polish).

- Nowaczyk, M.; Cieślik, K.; Waszak, M. Assessment of the Impact of Increased Physical Activity on Body Mass and Adipose Tissue Reduction in Overweight and Obese Children. Children (Basel). 2023, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in schoolaged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, T.; Sobiech, K.A.; Chwałczyńska, A. The effect of karate training on changes in physical fitness in school-age children with normal and abnormal body weight. PQ. 2019, 27, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Hernández, L.D.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Barrera-Gálvez, R.; Cabrera-Morales, M.D.C.; Reynoso-Vázquez, J.; Flores-Chávez, O.R.; Morales-Castillejos, L.; Cruz-Cansino, N.D.S.; Jiménez-Sánchez, R.C.; Arias-Rico, J. Effects of Strength Training on Body Fat in Children and Adolescents with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Children 2022, 9, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.; Brasil, I.; Monteiro, W.; Farinatti, P. Effects of physical activity on body mass and composition of school-age children and adolescents with overweight or obesity: Systematic review focusing on intervention characteristics. J. Bodyw. Mov. Therap. 2023, 33, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.A.; Davies, P.S. Habitual physical activity and physical activity intensity: Their relation to body composition in 5.0–10.5-y-old children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, X.; Xue, H.; Ni, X.; Yang, J.; Zou, Z.; Du, W. Association of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity with Childhood and Adolescent Overweight/Obesity: Findings from a Surveillance Project in Jiangsu Province of China. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratto, P.S.; Sangalli, C.N.; Leffa, P.D.S.; Valmorbida, J.L.; Vitolo, M.R. Associations between children's dietary patterns, excessive weight gain, and obesity risk: cohort study nested to a randomized field trial. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2025, 43, e2024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebestreit, A.; Intemann, T.; Siani, A.; De Henauw, S.; Eiben, G.; Kourides, Y.A.; Kovacs, E.; Moreno, L.A.; Veidebaum, T.; Krogh, V.; Pala, V.; Bogl, L.H.; Hunsberger, M.; Börnhorst, C.; Pigeot, I. Dietary patterns of European children and their parents in association with family food environment: Results from the I. Family Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Peláez, C.C.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Montero-Alonso, M.A.; González-Jiménez, E. Effect of Dietary and Physical Activity Interventions Combined with Psychological and Behavioral Strategies on Preventing Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Ferrão, J.; Fernandes, T. Nutritional Guidelines and Fermented Food Frameworks. Foods 2017, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, E.; Brown, T.; Rees, K.; Azevedo, L.B.; Whittaker, V.; Jones, D.; Olajide, J.; Mainardi, G.M.; Corpeleijn, E.; O’Malley, C.; Beardsmore, E.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Baur, L.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Demaio, A.; Ells, L.J. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD012651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, K.M.; Barnes, C.; Yoong, S.; Campbell, E.; Wyse, R.; Delaney, T.; Brown, A.; Stacey, F.; Davies, L.; Lorien, S.; Hodder, R.K. School-Based Nutrition Interventions in Children Aged 6 to 18 Years: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouardi, M.; Garcia-Llorens, G.; Valls-Belles, V. Childhood Obesity and Its Physiological Association with Sugar-Sweetened, Free-Sugar Juice, and Artificially Sweetened Beverages. Beverages. 2025, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Cena, H.; Magenes, VC; Vincenti, A.; Comola, G.; Beretta, A.; Di Napoli, I.; Zuccotti, G. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Metabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 702. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C.; Hall, A.; Nathan, N.; Sutherland, R.; McCarthy, N.; Pettet, M.; Brown, A.; Wolfenden, L. Efficacy of a school-based physical activity and nutrition intervention on child weight status: Findings from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2021, 153, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | SPA | EPA | ||||

| Completed (n=69) |

Dropped out (n=88) |

p | Completed (n=43) |

Dropped out (n=60) |

p | |

| Height (cm) | 155.95 | 156.26 | 0.78 | 153.15 | 153.06 | 0.940 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.59 | 62.37 | 0.620 | 54.11 | 54.08 | 0.987 |

| FM (kg) | 19.13 | 19.61 | 0.470 | 14.94 | 14.72 | 0.800 |

| Fat Mass (%) | 31.03 | 31.44 | 0.651 | 27.53 | 27.21 | 0.681 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.08 | 25.63 | 0.401 | 23.07 | 23.11 | 0.910 |

|

Measurement session |

SPA | EPA |

p* |

|||||

| Girls | Boys | Mean | Girls | Boys | Mean | |||

| Overweight | ||||||||

| Initial |

58.95% | 57.50% | 58.22% | 59.25% | 55.20% | 57.22% | 0.170 | |

| Final | 53.50% | 58.25% | 55.87% | 61.50% | 62.80% | 62.15% | 0.071 | |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| Initial | 41.05% | 42.50% | 41.77% | 40.75% | 48.80% | 44.77% | 0.245 | |

| Final | 46.50% | 41.75% | 44.13% | 38.50% | 37.24% | 37.87% | 0.050 | |

| A change in the BMI category from overweight to normal | ||||||||

| Entire study period | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.70% | 12.5% | 8.10% | 0.000 | |

| Indicator | Baseline all group (95% CI) |

Final all group (95% CI) |

p | SPA | EPA | ||||

| Baseline (95% CI) |

Final (95% CI) |

P | Baseline (95% CI) |

Final (95% CI) |

P | ||||

| Height (cm) | 151.42 (4.75-8.31) |

157.65 (7.68-9.25) |

0.061 | 152.50 (6.29-8.18) |

159.41 (7.02-9.02) |

0.077 | 150.42 (5.03-8.52) |

155.88 (5.66-7.67) |

0.067 |

| Weight (kg) | 54.38 (7.63-9.29) |

61.32 (9.25-10.15) |

0.042 | 57.81 (5.61-9.47) |

65.37 (8.12-11.18) |

0.034 | 50.94 (3.85-5.16) |

57.28 (5.33-9.25) |

0.060 |

| FM (kg) | 29.35 (4.00-5.31) |

29.21 (6.25-9.02) |

0.871 | 30.62 (2.32-3.19) |

31.44 (6.12-7.18) |

0.069 | 28.08 (4.19-5.85) |

26.98 (4.25-8.25) |

0.074 |

| Fat Mass (%) | 16.01 (3.31-4.32) |

18.07 (7.54-9.45) |

0.074 | 17.67 (2.77-4.68) |

20.59 (7.66-9.14) |

0.057 | 14.35 (2.81-5.75) |

15.54 (3.35-6.69) |

0.087 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.58 (1.09-2.90) |

24.57 (2.40-3.19) |

0.690 | 24.65 (1.34-2.26) |

25.51 (3.74-6.25) |

0.097 | 22.51 (1.26-2.59) |

23.62 (1.70-3.47) |

0.098 |

| BMI (percentile) | 90th (2.14-3.80) |

97th (2.35-3.14) |

0.078 | 97th (3.18-4.36) |

97th (2.55-3.17) |

0.740 | 90th (2.97-3.14) |

90th (1.58-2.66) |

0.840 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).