Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Body Mass Index

2.4. Questionnaire

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group Characteristics

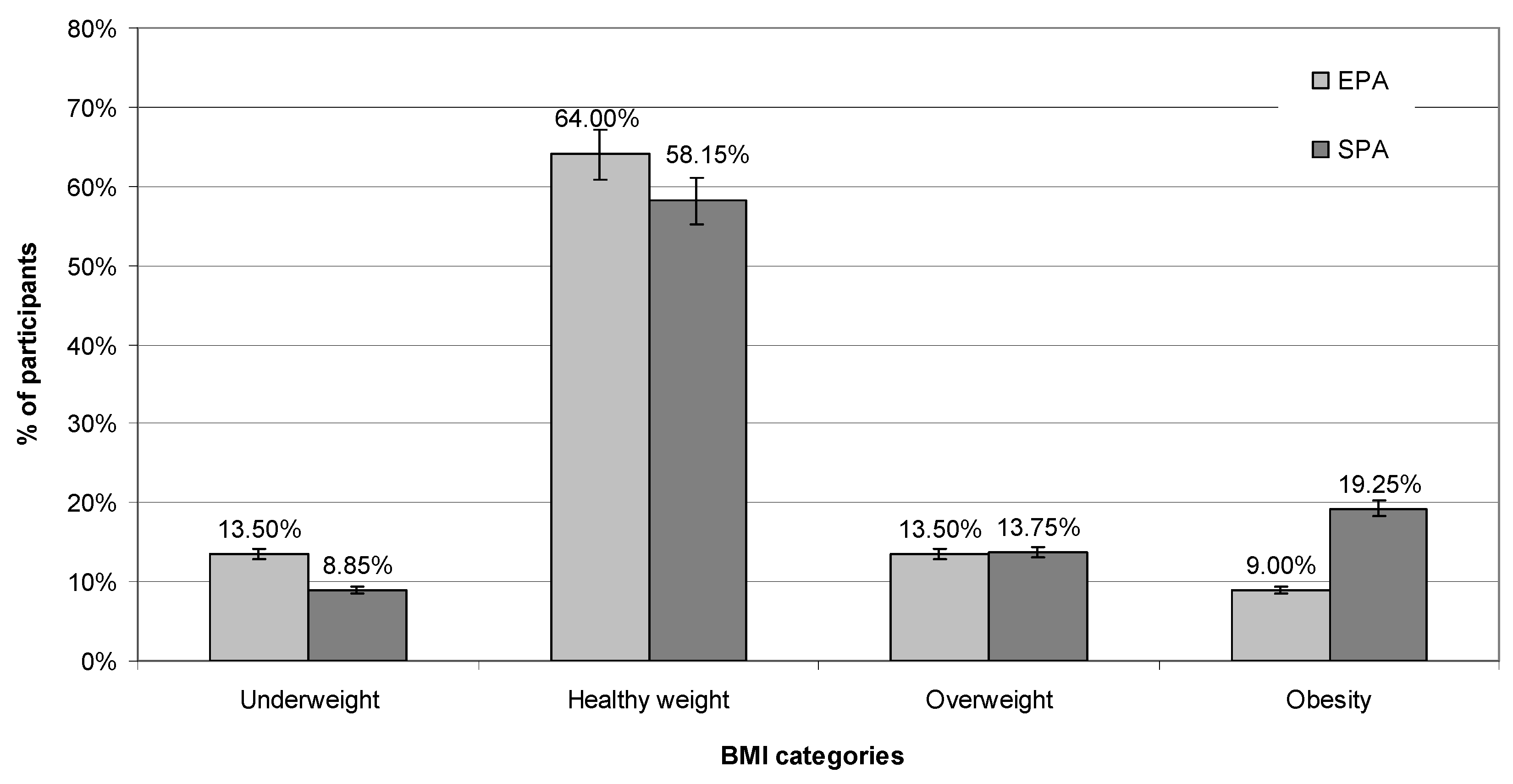

3.2. BMI

3.1. BMI

3.2. Nutritional behavior

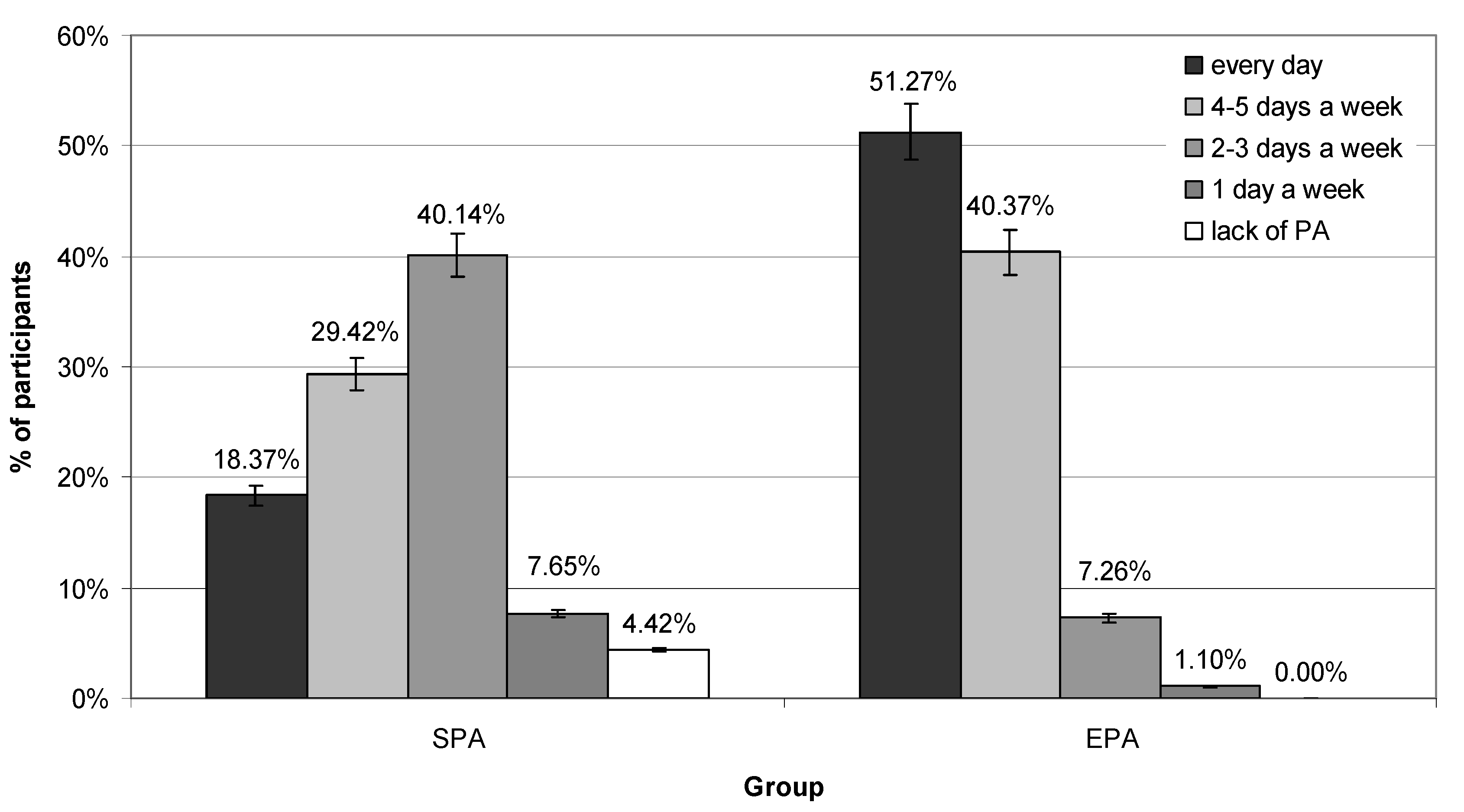

3.3. Extra-Curricular PA

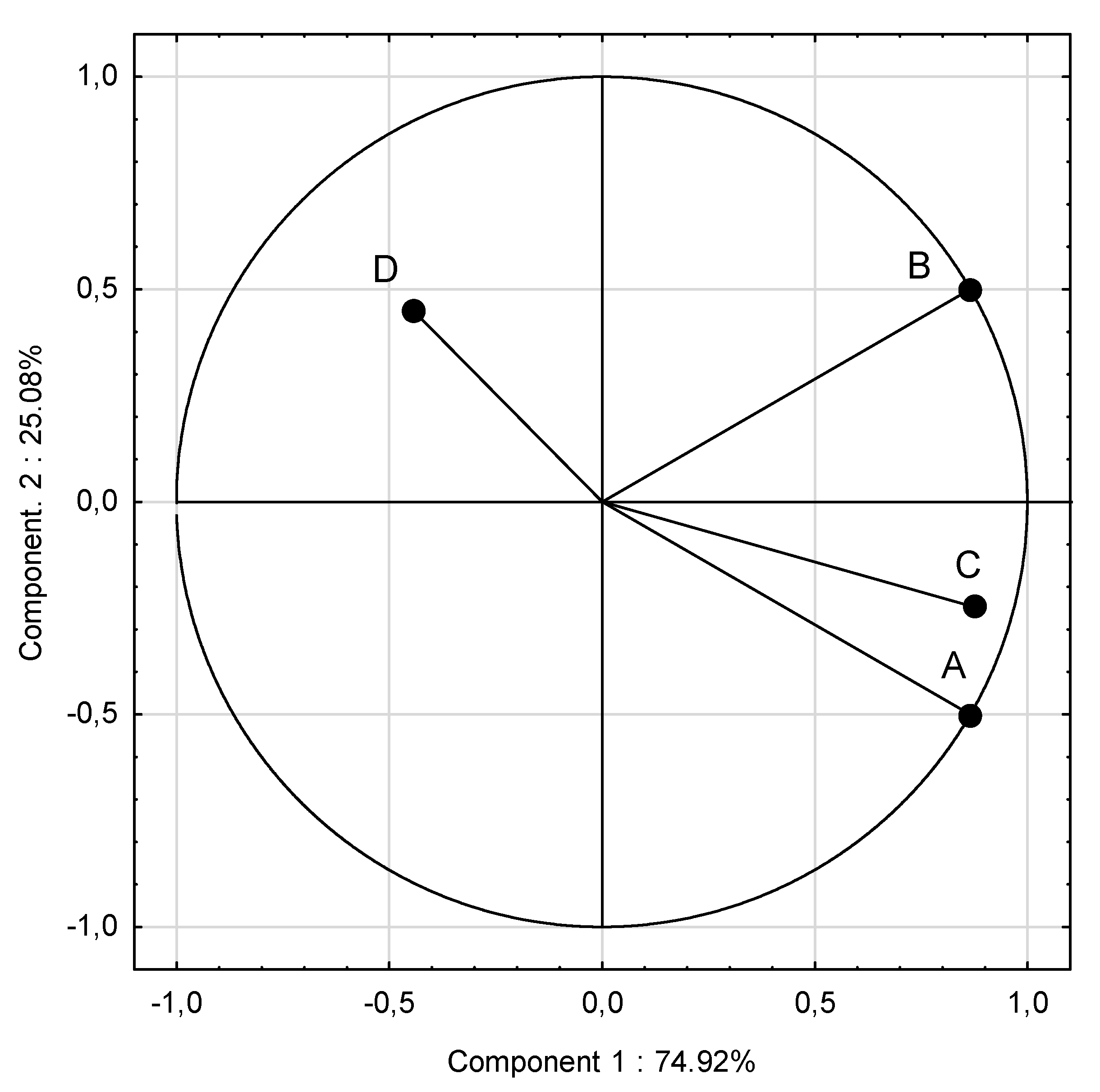

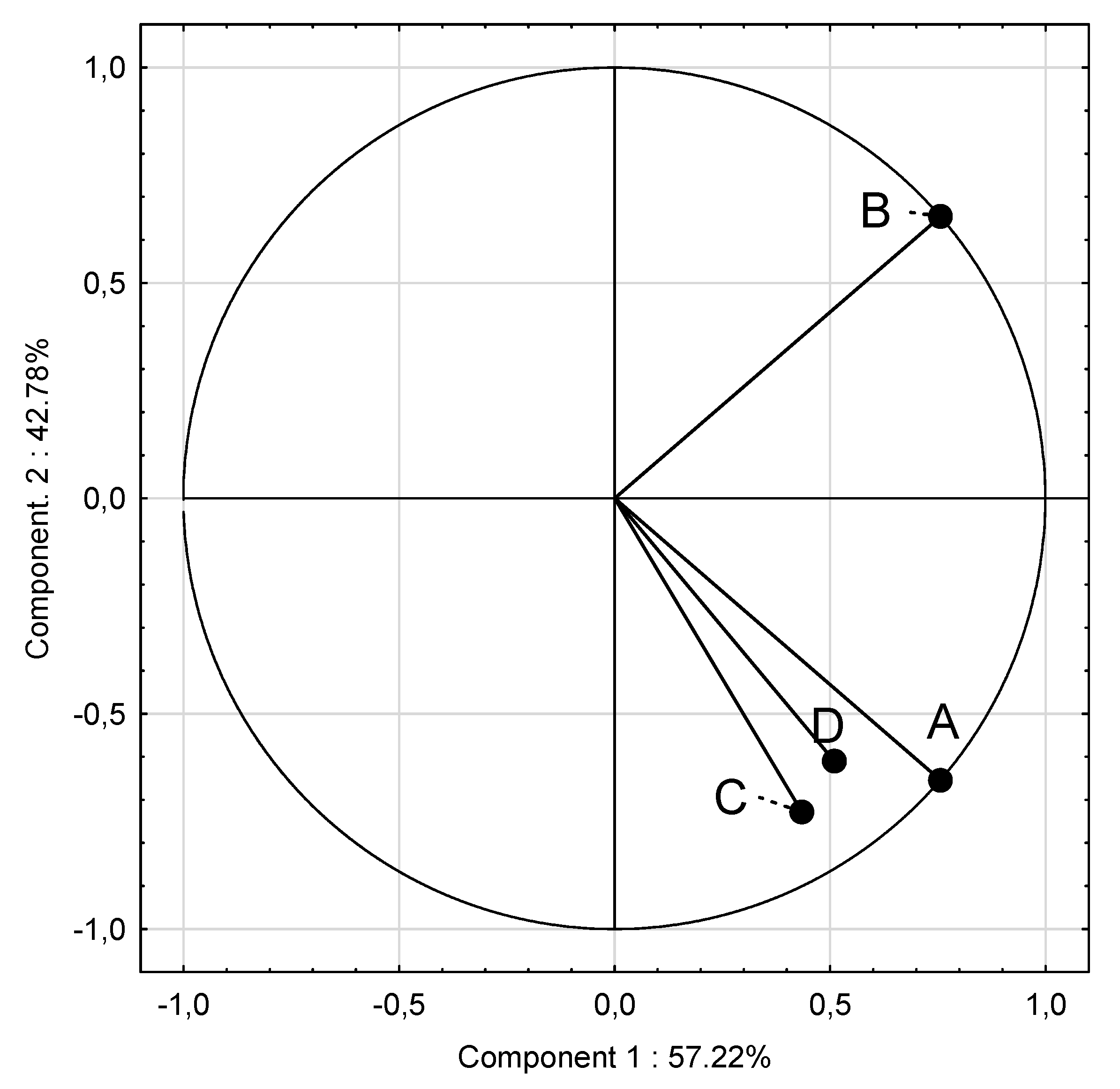

3.4. PCA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DiPietro, L.; Buchner, D.M.; Marquez, D.X.; Pate, R.R.; Pescatello, L.S.; Whitt-Glover, M.C. New scientific basis for the 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines. J Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; Kakuma, R.; Kennedy, E.; Mahon, J.; McGovern, T.; Mokdad, A.H.; Patel, V.; Petroni, S.; Reavley, N.; Taiwo, K.; Waldfogel, J.; Wickremarathne, D.; Barroso, C.; Bhutta, Z.; Fatusi, A.O.; Mattoo, A.; Diers, J.; Fang, J.; Ferguson, J.; Ssewamala, F.; Viner, R.M. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.C.; Lawlor, D.A.; Kimm, S.Y. Childhood obesity. Lancet. 2010, 375, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Obesity Federation, World Obesity Atlas 2023. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=19 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen 2022. (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; Dempsey, P.C.; DiPietro, L.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Garcia, L.; Gichu, M.; Jago, R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lambert, E.; Leitzmann, M.; Milton, K.; Ortega, F.B.; Ranasinghe, C.; Stamatakis, E.; Tiedemann, A.; Troiano, R.P.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Wari, V.; Willumsen, J.F. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górna, S.; Pazdro-Zastawny, K.; Basiak-Rasała, A.; Krajewska, J.; Kolator, M.; Cichy, I.; Rokita, A.; Zatoński, T. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors in Polish children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr. 2023, 30, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. WHO.; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020.

- Eddolls, W.T.B.; McNarry, M.A.; Stratton, G.; Winn, C.O.N.; Mackintosh, K.A. High-Intensity Interval Training Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2363–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. The Impact of Physical Activity at School on Children’s Body Mass during 2 Years of Observation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.K.; Hairi, N.N.; Jalaludin, M.Y.; Majid, H.A. Dietary intake, physical activity and muscle strength among adolescents: The Malaysian Health and Adolescents Longitudinal Research Team (MyHeART) study. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e026275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Carrasco, S.; Felipe, J.L.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J.; Hernandez-Martin, A.; Clavel, I.; Gallardo, L.; Garcia-Unanue, J. Relationship between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Body Composition with Physical Fitness Parameters in a Young Active Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, L.K.; Canadian Paediatric Society. Paediatric Sports and Exercise Medicine Section Sport nutrition for young athletes. Paediatr. Child Health. 2013, 18, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. Eating Behaviour and Physical Fitness in 10-Year-Old Children Attending General Education and Sports Classes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortch, K.S.; Gay, J.; Springer, A.; Kohl, H.W.; Sharma, S.; Saxton, D.; Wilson, K.; Hoelscher, D. The Association between Sport Participation and Dietary Behaviors among Fourth Graders in the School Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey, 2009–2010. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2014, 29, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1·6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygas, W.; Gajewska, M.; Zdrojewski, T. Niedostateczny Poziom Aktywności Fizycznej w Polsce Jako Zagrożenie i Wyzwanie Dla Zdrowia Publicznego. Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego—Państwowy Zakład Higieny; Warsaw, Poland: 2021.

- López-Gil, J.F.; García-Hermoso, A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Kales, S.N. Mediterranean Diet-Based Interventions to Improve Anthropometric and Obesity Indicators in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv Nutr. 2023, 14, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lacoba, R.; Pardo-Garcia, I.; Amo-Saus, E.; Escribano-Sotos, F. Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: a systematic meta-review. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018, 28, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E.; Singer, M. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change. Lancet. 2019, 393, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Dallolio, L.; Sanmarchi, F.; Lovecchio, F.; Falato, M.; Longobucco, Y.; Lanari, M.; Sacchetti, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Children and Adolescents and Association with Multiple Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodowe Centrum Edukacji Żywieniowej. Talerz zdrowego żywienia. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz-zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Mazur, J.; Małkowska-Szkutnik, A.; editor. Zdrowie uczniów w 2018 roku na tle nowego modelu badań HBSC. Mother and Child Institute, Warsaw. Available online: https://imid.med.pl/files/imid/Aktualnosci/Aktualnosci/raport%20HBSC%202018.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułaga, Z.; Różdżyńska, A.; Palczewska, I. Percentile charts of height, body mass and body mass index in children and adolescents in Poland—Results of the OLAF study. Stand. Med. Pediatr. 2010, 7, 690–700. [Google Scholar]

- Kułaga, Z.; Grajda, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Góźdź, M.; Wojtyło, M.; Świąder, A.; Różdżyńska-Świątkowska, A.; Litwin, M. Polish 2012 growth references for preschool children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gawęcki, J.; Wądołowska, L.; et al. Kwestionariusz do badania poglądów i zwyczajów żywieniowych dla osób w wieku od 16 do 65 lat. KomPAN, Warsaw: 2020. p. 22–34.

- Ługowska, K.; Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J. The Impact of Physical Activity at School on Children’s Body Mass during 2 Years of Observation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Bull World Health Organ. 2013, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski, W.; Ługowska, K. The Effectiveness of Physical Activity Intervention at School on BMI and Body Composition in Overweight Children: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfell-Jones, M.; Old, T.; Steward, A.; Carter, J.E.L. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment; ISAK: Palmerston North, New Zeland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tanita SC-240MA Instruction Manual. Tanita User Manual SC 240 MA. Available online: https://www.manualslib.com/manual/1065295/Tanita-Sc-240ma.html (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Orsso, C.E.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Maisch, M.J.; Haqq, A.M.; Prado, C.M. Using bioelectrical impedance analysis in children and adolescents: Pressing issues. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaczyk, M.; Cieślik, K.; Waszak, M. Assessment of the Impact of Increased Physical Activity on Body Mass and Adipose Tissue Reduction in Overweight and Obese Children. Children (Basel). 2023, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, D.; He, M.; Han, D.; Su. D.; Zhang, R. Food and Nutrient Intake in Children and Adolescents with or without Overweight/Obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, A.; Łuszczki, E.; Kuchciak, M.; Bobula, G.; Oleksy, Ł.; Stolarczyk, A.; Dereń, K. Children’s Body Mass Index Depending on Dietary Patterns, the Use of Technological Devices, the Internet and Sleep on BMI in Children. Int. J. Environ. Re.s Public Health. 2020, 17, 7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, C.; Mascherini, G.; Bini, V.; Anania, G.; Calà, P.; Toncelli, L.; Galanti, G. Integrated total body composition versus Body Mass Index in young athletes. Minerva Pediatr. 2020, 72, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, N.M.D.S.; Leal, V.S.; Oliveira, J.S.; Andrade, M.I.S.; Santos, NF.D.; Pessoa, J.T.; Aquino, N.B.; Lira, P.I.C. Excess weight in adolescents and associated factors: data from the ERICA study. J. Pediatr. (Rio J). 2021, 97, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with health education to reduce body mass index in adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Skolmowska, D.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Nałęcz, H.; Mellová, B.; Żywczyk, K.; Baj-Korpak, J.; Gutkowska, K. Influence of Food Habits and Participation in a National Extracurricular Athletics Program on Body Weight within a Pair-Matched Sample of Polish Adolescents after One Year of Intervention-goathletics Study. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słowik, J.; Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Maciejewska-Paszek, I.; Kardas, M.; Niewiadomska, E.; Szostak-Trybuś, M.; Palka-Słowik, M.; Irzyniec, T. Nutritional Status Assessment in Children and Adolescents with Various Levels of Physical Activity in Aspect of Obesity. Obes. Facts. 2019, 12, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, T.; Akcam, M.; Serdaroglu, F.; Dereci, S. Breakfast habits, dairy product consumption, physical activity, and their associations with body mass index in children aged 6–18. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, B.; Tombeau Cost, K.; Fuller, A.; Birken, C.S.; Anderson, L.N. Sex and gender differences in childhood obesity: Contributing to the research agenda. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health. 2020, 3, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, S.; Neuenschwander, M.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Bechthold, A.; Boeing, H.; Schwingshackl, L. Food Groups and Risk of Overweight, Obesity, and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato-Carretero, P.; Roncero-Martín, R.; Pedrera-Zamorano, J.D.; López-Espuela, F.; Puerto-Parejo, L.M.; Sánchez-Fernández, A.; Canal-Macías, M.L.; Moran, J.M.; Lavado-García, J.M. Long-Term Dietary and Physical Activity Interventions in the School Setting and Their Effects on BMI in Children Aged 6-12 Years: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Healthcare (Basel). 2021, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M.K.; Johansen, B.T.; Haugland, S.H.; Stea, T.H. Participation in organized sports is associated with decreased likelihood of unhealthy lifestyle habits in adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2018, 28, 2384–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulka, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Hoffmann, M.; Kowalkowska, J.; Gutkowska, K. Effect of an Education Program on Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes toward Nutrition, Diet Quality, Lifestyle, and Body Composition in Polish Teenagers. The ABC of Healthy Eating Project: Design, Protocol, and Methodology. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Diamantis, D.V.; Notara, V.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Extracurricular Sports Participation and Sedentary Behavior in Association with Dietary Habits and Obesity Risk in Children and Adolescents and the Role of Family Structure: a Literature Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröberg, A.; Lindroos, A.K.; Moraeus, L.; Patterson, E.; Warensjö Lemming, E.; Nyberg, G. Leisure-time organised physical activity and dietary intake among Swedish adolescents. J. Sports. Sci. 2022, 40, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, I.Y.; Reicks, M. Relationship between whole-grain intake, chronic disease risk indicators, and weight status among adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archero, F.; Ricotti, R.; Solito, A.; Carrera, D.; Civello, F.; Di Bella, R.; Bellone, S.; Prodam, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among School Children and Adolescents Living in Northern Italy and Unhealthy Food Behaviors Associated to Overweight. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Ramírez, L. Exploring the Influence of a Physical Activity and Healthy Eating Program on Childhood Well-Being: A Comparative Study in Primary School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2024, 21, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hammond-Bennett, A.; Hypnar, A.; Mason, S. Health-related physical fitness and physical activity in łelementary school students. BMC Public Health. 2018, 18, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán Carrillo, V.J.; Sierra, A.C.; Jiménez Loaisa, A.; González-Cutre, D.; Martínez Galindo, C.; Cervelló, E. Diferencias según género en el tiempo empleado por adolescentes en actividad sedentaria y actividad física en diferentes segmentos horarios del día (Gender differences in time spent by adolescents in sedentary and physical activity in different day segmen. Retos. Digit. 2016, 31, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Pino, I.; López-Castedo, A.; Martínez-Patiño, M.J.; Valverde-Esteve, T.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Gender Differences in Motivation and Barriers for The Practice of Physical Exercise in Adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnberg, J.; Perez-Farinos, N.; Benavente-Marin, J.C.; Gomez, S.F.; Labayen, I.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Gonzalez-Valeiro, M.; et al. Screen Time and Parents’ Education Level Are Associated with Poor Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish Children and Adolescents: The PASOS Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, F.; Varnaccia, G.; Zeiher, J.; Lange, C.; Jordan, S. Influencing factors of obesity in school-age children and adolescents—A systematic review of the literature in the context of obesity monitoring. J. Health Monit. 2020, 5, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Llargues, E.; Franco, R.; Recasens, A.; Nadal, A.; Vila, M.; Perez, M.J.; Manresa, J.M.; Recasens, I.; Salvador, G.; Serra, J.; et al. Assessment of a school-based intervention in eating habits and physical activity in school children: The AVall study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2011, 65, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyniak, A.; Traczyk, I. Nutrition-Related Knowledge and Nutrition-Related Practice among Polish Adolescents-A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | Groups | |||||||||||

| Mean total |

SPA | EPA | p | |||||||||

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | SD | Mean | Median | Min | Max | SD | |||

| Height (cm) | 167.23 | 167.57 | 166.50 | 147.00 | 186.00 | 8.39 | 166.83 | 167.00 | 146.00 | 182.00 | 7.01 | 0.148 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.90 | 61.24 | 58.85 | 37.80 | 109.20 | 14.78 | 58.36 | 57.90 | 29.90 | 93.20 | 120.02 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.30 | 21.70 | 21.00 | 15.40 | 36.50 | 4.46 | 20.84 | 20.50 | 14.00 | 30.00 | 3.44 | 0.012 |

| Girls | ||||||||||||

| Height (cm) | 164.67 | 164.82 | 164.00 | 152.00 | 180.00 | 5.90 | 164.52 | 164.00 | 149.00 | 182.00 | 5.92 | 0.217 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.19 | 58.61 | 55.65 | 37.80 | 99.50 | 12.99 | 55.60 | 53.80 | 40.10 | 80.10 | 10.09 | 0.041 |

| BMI (kg/m2) / percentile |

21.06 | 21.58 75th |

20.20 | 16.20 | 36.50 | 4.73 | 20.48 50th |

20.30 | 14.80 | 29.40 | 3.26 | 0.035 |

| Boys | ||||||||||||

| Height (cm) | 169.76 | 170.24 | 170.00 | 147.00 | 186.00 | 9.55 | 169.20 | 170.00 | 146.00 | 182.00 | 7.30 | 0.723 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.58 | 63.78 | 61.05 | 37.80 | 109.20 | 16.02 | 61.17 | 61.00 | 29.90 | 93.20 | 13.23 | 0.021 |

| BMI (kg/m2) / percentile |

21.53 | 21.81 75th |

21.15 | 15.40 | 33.70 | 4.23 | 21.20 50th |

21.20 | 14.00 | 30.00 | 3.60 | 0.043 |

| BMI categories | Mean | Groups | |||||

| SPA | EPA | ||||||

| Boys | Girls | p | Boys | Girls | p | ||

| Underweight | 11.17 | 7.00 | 10.70 | 0.001 | 15.00 | 12.00 | 0.001 |

| Normal | 61.07 | 61.00 | 55.30 | 0.000 | 65.00 | 63.00 | 0.041 |

| Overweight | 13.63 | 15.00 | 12.50 | 0.024 | 12.00 | 15.00 | 0.034 |

| Obesity | 14.13 | 17.00 | 21.50 | 0.001 | 8.00 | 10.00 | 0.000 |

|

No |

Foods |

Group |

Frequency of consumption [%] |

p* |

|||||

| Never | 1–3 times a month | Once a week | Several times a week | Once a day | Several times a day | ||||

| 1. | Milk | SPA | 3.00 | 5.00 | 23.00 | 38.00 | 19.00 | 12.00 |

0.415 |

| EPA | 2.00 | 6.00 | 15.00 | 36.00 | 29.00 | 13.00 | |||

| 2. | Yoghurts (natural and flavoured) | SPA | 13.00 | 18.00 | 17.00 | 41.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 |

0.221 |

| EPA | 7.00 | 14.00 | 20.00 | 46.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | |||

| 3. | Cottage chesses | SPA | 17.00 | 27.00 | 29.00 | 21.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 |

0.000 |

| EPA | 15.00 | 25.00 | 20.00 | 30.00 | 8.00 | 4.00 | |||

| 4. | High fat cheses (including processed and blue cheses) | SPA | 4.00 | 11.00 | 23.00 | 43.00 | 16.00 | 4.00 |

0.078 |

| EPA | 4.00 | 13.00 | 21.00 | 41.00 | 18.00 | 5.00 | |||

| 5. | White bread and rolls | SPA | 1.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 13.00 | 29.00 | 52.00 |

0.431 |

| EPA | 2.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 16.00 | 26.00 | 48.00 | |||

| 6. | Whole grain bread and rolls | SPA | 13.00 | 20.00 | 28.00 | 21.00 | 11.00 | 8.00 |

0.001 |

| EPA | 15.00 | 23.00 | 15.00 | 26.00 | 13.00 | 10.00 | |||

| 7. | White rice, white pasta, fine-grained groats | SPA | 5.00 | 10.00 | 61.00 | 20.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

0.611 |

| EPA | 2.00 | 17.00 | 55.00 | 19.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |||

| 8. | Oatmeal, whole grain pasta, coarse-grained groats, buckwheat groats | SPA | 9.00 | 19.00 | 43.00 | 26.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

0.012 |

| EPA | 1.00 | 17.00 | 57.00 | 17.00 | 4.00 | 5.00 | |||

| 9. | Poultry dishes | SPA | 3.00 | 10.00 | 43.00 | 36.00 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 0.024 |

| EPA | 5.00 | 11.00 | 31.00 | 40.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | |||

| 10. | Red meat dishes | SPA | 7.00 | 18.00 | 56.00 | 18.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

0.041 |

| EPA | 13.00 | 27.00 | 45.00 | 13.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 11. | Cold cuts, sausages, frankfurters | SPA | 17.00 | 6.00 | 17.00 | 21.00 | 19.00 | 20.00 |

0.047 |

| EPA | 11.00 | 6.00 | 16.00 | 33.00 | 19.00 | 16.00 | |||

| 12 | Canned meats | SPA | 60.00 | 35.00 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.069 |

| EPA | 78.00 | 21.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 13. | Fried meat or flour dishes | SPA | 0.00 | 4.00 | 21.00 | 47.00 | 26.00 | 4.00 | 0.067 |

| Fried meat or flour dishes | EPA | 0.00 | 2.00 | 24.00 | 54.00 | 20.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 14. | Eggs | SPA | 5.00 | 19.00 | 50.00 | 26.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.023 |

| EPA | 7.00 | 18.00 | 59.00 | 10.00 | 6.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 15. | Fish | SPA | 20.00 | 30.00 | 49.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.021 |

| EPA | 8.00 | 35.00 | 56.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 16. | Legumes | SPA | 33.00 | 44.00 | 15.00 | 9.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.067 |

| EPA | 29.00 | 39.00 | 19.00 | 11.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 17. | Fruit | SPA | 3.00 | 3.00 | 8.00 | 29.00 | 26.00 | 33.00 | 0.003 |

| EPA | 0.00 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 25.00 | 28.00 | 41.00 | |||

| 18. | Vegetables | SPA | 3.00 | 4.00 | 14.00 | 24.00 | 30.00 | 26.00 | 0.027 |

| EPA | 2.00 | 1.00 | 17.00 | 10.00 | 25.00 | 36.00 | |||

| 19. | Butter as an addition to bread or dishes, for frying, baking, etc. | SPA | 3.00 | 4.00 | 14.00 | 21.00 | 40.00 | 19.00 | 0.044 |

| EPA | 6.00 | 10.00 | 14.00 | 18.00 | 36.00 | 18.00 | |||

| 20. | Lard as an addition to bread or dishes, for frying, baking, etc. | SPA | 89.00 | 12.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.067 |

| EPA | 95.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 21. | Fast food, different types | SPA | 2.00 | 33.00 | 53.00 | 13.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.041 |

| EPA | 6.00 | 45.00 | 47.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 22. | Sweets, candies, chocolate, bars | SPA | 2.00 | 8.00 | 16.00 | 22.00 | 36.00 | 18.00 | 0.001 |

| EPA | 2.00 | 13.00 | 21.00 | 36.00 | 17.00 | 12.00 | |||

| 23. | Juices | SPA | 10.00 | 19.00 | 45.00 | 21.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 0.065 |

| EPA | 8.00 | 18.00 | 47.00 | 16.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | |||

| 24. | Sweetened carbonated or non-carbonated drinks | SPA | 14.00 | 22.00 | 32.00 | 19.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 0.003 |

| EPA | 22.00 | 41.00 | 24.00 | 9.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 25. | Energy drinks | SPA | 65.00 | 24.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.062 |

| EPA | 73.00 | 19.00 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

|

No |

Foods |

Group |

Frequency of consumption [%] |

p* |

|||||

| Never | 1–3 times a month | Once a week | Several times a week | Once a day | Several times a day | ||||

| 1. | Milk | Girls | 4.00 | 7.00 | 19.00 | 30.00 | 29.00 | 12.00 |

0.415 |

| Boys | 1.00 | 5.00 | 19.00 | 43.00 | 19.00 | 13.00 | |||

| 2. | Yoghurts (natural and flavoured) | Girls | 10.00 | 17.00 | 21.00 | 41.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 |

0.061 |

| Boys | 10.00 | 15.00 | 16.00 | 46.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | |||

| 3. | Cottage chesses | Girls | 18.00 | 23.00 | 27.00 | 22.00 | 8.00 | 3.00 |

0.078 |

| Boys | 14.00 | 29.00 | 22.00 | 29.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | |||

| 4. | High fat chesses (including processed and blue chesses) | Girls | 4.00 | 11.00 | 24.00 | 40.00 | 17.00 | 5.00 |

0.072 |

| Boys | 4.00 | 13.00 | 19.00 | 44.00 | 17.00 | 4.00 | |||

| 5. | White bread and rolls | Girls | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 20.00 | 31.00 | 42.00 |

0.010 |

| Boys | 2.00 | 3.00 | 6.00 | 9.00 | 24.00 | 58.00 | |||

| 6. | Whole grain bread and rolls | Girls | 16.00 | 21.00 | 19.00 | 22.00 | 13.00 | 11.00 |

0.023 |

| Boys | 12.00 | 22.00 | 23.00 | 26.00 | 11.00 | 7.00 | |||

| 7. | White rice, white pasta, fine-grained groats | Girls | 6.00 | 15.00 | 56.00 | 18.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 |

0.920 |

| Boys | 3.00 | 12.00 | 58.00 | 22.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | |||

| 8. | Oatmeal, whole grain pasta, coarse-grained groats, buckwheat groats | Girls | 5.00 | 20.00 | 53.00 | 17.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

0.028 |

| Boys | 5.00 | 15.00 | 46.00 | 25.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | |||

| 9. | Poultry dishes | Girls | 6.00 | 11.00 | 43.00 | 30.00 | 8.00 | 3.00 |

0.035 |

| Boys | 2.00 | 10.00 | 39.00 | 37.00 | 5.00 | 7.00 | |||

| 10. | Red meat dishes | Girls | 9.00 | 26.00 | 54.00 | 12.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

0.020 |

| Boys | 8.00 | 17.00 | 51.00 | 20.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 11. | Cold cuts, sausages, frankfurters | Girls | 19.00 | 9.00 | 21.00 | 27.00 | 11.00 | 13.00 |

0.001 |

| Boys | 10.00 | 4.00 | 11.00 | 26.00 | 27.00 | 23.00 | |||

| 12 | Canned meats | Girls | 70.00 | 29.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

0.201 |

| Boys | 68.00 | 27.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 13. | Fried meat or flour dishes | Girls | 0.00 | 6.00 | 24.00 | 48.00 | 21.00 | 3.00 |

0.580 |

| Boys | 0.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 52.00 | 25.00 | 2.00 | |||

| 14. | Eggs | Girls | 6.00 | 24.00 | 53.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

0.068 |

| Boys | 7.00 | 13.00 | 56.00 | 19.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 15. | Fish | Girls | 20.00 | 35.00 | 42.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

0.047 |

| Boys | 13.00 | 35.00 | 52.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 16. | Legumes | Girls | 31.00 | 40.00 | 18.00 | 11.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

0.091 |

| Boys | 32.00 | 43.00 | 16.00 | 9.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 17. | Fruit | Girls | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 24.00 | 23.00 | 46.00 |

0.010 |

| Boys | 3.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 28.00 | |||

| 18. | Vegetables | Girls | 2.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 | 20.00 | 25.00 | 37.00 |

0.023 |

| Boys | 3.00 | 5.00 | 15.00 | 24.00 | 30.00 | 25.00 | |||

| 19. | Butter as an addition to bread, dishes, for frying, baking, etc. | Girls | 5.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 22.00 | 35.00 | 18.00 |

0.028 |

| Boys | 4.00 | 4.00 | 17.00 | 17.00 | 41.00 | 19.00 | |||

| 20. | Lard as an addition to bread, dishes, for frying, baking, etc. | Girls | 90.00 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

0.810 |

| Boys | 94.00 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 21. | Fast food, different types | Girls | 6.00 | 41.00 | 46.00 | 9.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

0.043 |

| Boys | 2.00 | 37.00 | 55.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 22. | Sweets, candies, chocolate, bars | Girls | 2.00 | 9.00 | 17.00 | 30.00 | 27.00 | 17.00 |

0.240 |

| Boys | 2.00 | 11.00 | 21.00 | 28.00 | 27.00 | 12.00 | |||

| 23. | Juices | Girls | 11.00 | 19.00 | 43.00 | 17.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 |

0.610 |

| Boys | 7.00 | 18.00 | 49.00 | 21.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |||

| 24. | Sweetened carbonated or non-carbonated drinks | Girls | 23.00 | 33.00 | 29.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 0.020 |

| sweetened carbonated or non-carbonated drinks | Boys | 14.00 | 30.00 | 26.00 | 18.00 | 9.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 25. | Energy drinks | Girls | 76.00 | 19.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.038 |

| Boys | 62.00 | 24.00 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).