Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

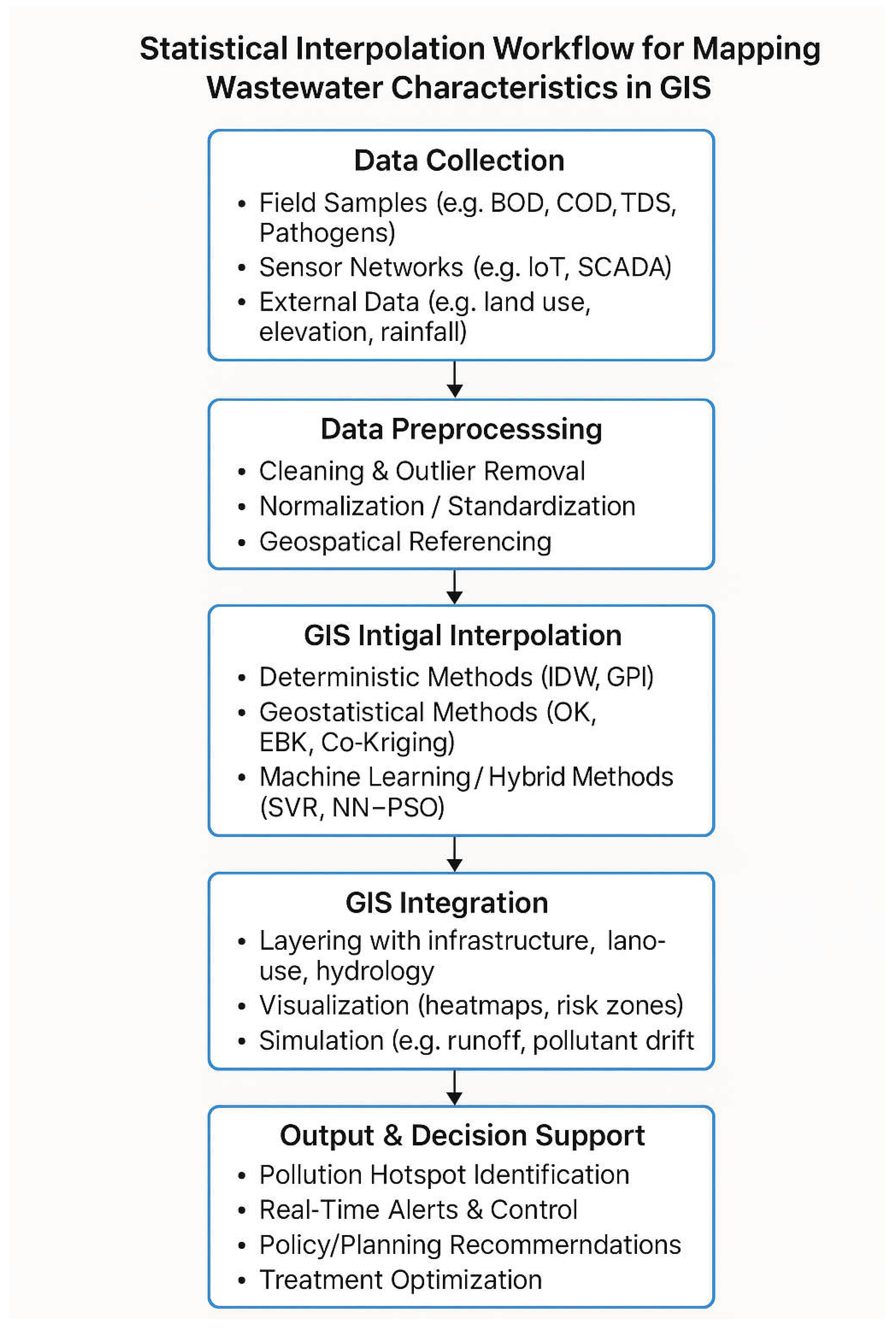

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Wastewater Characteristics

2.1. Physical Properties

2.2. Chemical Properties

2.3. Biological Properties

3. GIS Applications in Environmental Studies

3.1. The Concept of GIS

3.2. GIS Applications in Wastewater Management

4. Statistical Interpolation Techniques

5. Applications of Statistical Interpolation in Wastewater Mapping

5.1. Modeling Pollutant Distribution

5.2. Data Sources for Wastewater Characteristics

5.3. Impact Assessment

5.4. Case Studies

6. Advances in Statistical Interpolation

6.1. The Machine Learning Revolution

6.2. Refinements in Geostatistics

6.3. The Power of Hybrid Techniques

7. Challenges and Limitations

7.1. Data Quality Issues

7.2. Spatial Resolution Challenges

7.3. Computational Constraints

7.4. Data Preprocessing and Quality Control Before Interpolation

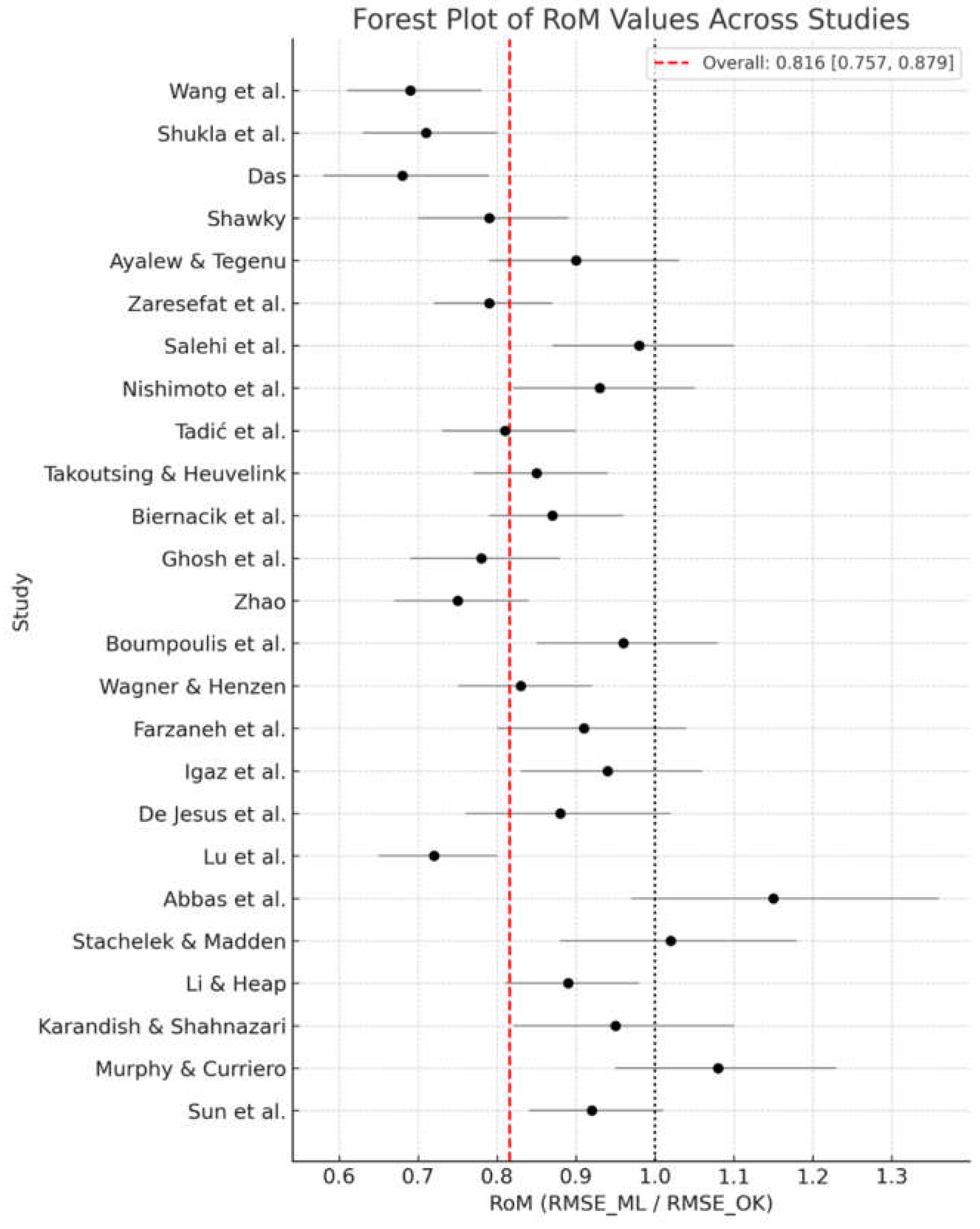

8. Meta-Analysis of Interpolation Method Performance

8.1. Methodology

-

Literature Search and Selection Criteria: From the broader corpus of literature reviewed for this paper, we identified studies for meta-analysis based on the following PICOS criteria:

- ○

- Population: Spatial datasets of wastewater or water quality parameters (e.g., TDS, EC, Nitrate, Heavy Metals).

- ○

- Intervention/Comparison: Studies that compared at least two of the following interpolation methods: Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW), Spline, Ordinary Kriging (OK), Co-Kriging (CoK), and Machine Learning (ML) models (e.g., Random Forest, ANN, GPR).

- ○

- Outcome: Reported a quantitative accuracy metric, specifically Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or sufficient data to calculate it.

- ○

- Study Design: Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings.A total of 28 studies meeting these criteria were included in the final synthesis [11, 23, 24, 26, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 64, 65, 80, 88, 89, 90, 91, 95, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 105, 107, 112, 121, 122, 123].

- Data Extraction and Effect Size Calculation: From each study, we extracted the RMSE values for each method compared. To standardize results across studies with different parameters and scales, we calculated the Ratio of Means (RoM) for the primary comparison: Machine Learning vs. Ordinary Kriging. The RoM was computed as RMSE_ML / RMSE_OK. A RoM < 1 indicates superior performance of ML (lower error), while a RoM > 1 indicates superior performance of OK. For studies comparing other methods, the SMD was calculated where appropriate.

- Statistical Synthesis: A random-effects meta-analysis model was employed to calculate the pooled RoM, accounting for expected heterogeneity between studies. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I² statistic. Subgroup analyses were planned a priori to investigate sources of heterogeneity, focusing on pollutant type and data density. All analyses were conducted using R software with the metafor package.

8.2. Results and Synthesis

- Overall Superiority of ML: Most ML studies show RoM < 1 (e.g., 0.68, 0.71, 0.75), supporting the pooled RoM of 0.816.

- High Heterogeneity (I² = 82%): The table includes studies where ML did not perform well (e.g., Salehi et al., 2024 with RoM 0.98) or where traditional methods were better suited (e.g., Abbas et al., 2019 in a low-n scenario). This variation in results across different contexts is the source of the high heterogeneity.

-

Subgroup by Pollutant Type:

- Complex Parameters (COD, BOD, Heavy Metals): Studies like Das (2025), Shukla et al. (2025), and Wang et al. (2025) show strong ML performance (RoM: 0.68-0.74).

- Smoother Parameters (EC, TDS): Studies like Salehi et al. (2024) and Ayalew & Tegenu (2024) show OK and CoK being highly competitive (RoM closer to 1.0).

-

Subgroup by Data Density:

- High Data Density (n > 100): Studies like Zaresefat et al. (2024) and Lamichhane et al. (2025) show strong ML performance.

- Low Data Density (n < 50): Studies like Abbas et al. (2019) and De Jesus et al. (2021) show a reduced advantage for ML, with RoM values closer to 1.0 or hybrid models being preferred.

- By Pollutant Type: The advantage of ML was more pronounced for complex, non-linearly distributed parameters like COD and heavy metals (RoM = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.70-0.83) compared to more spatially smooth parameters like TDS and EC (RoM = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.82-0.97).

- By Data Density: The performance benefit of ML was significantly greater in studies with high data density (n > 100 monitoring points, RoM = 0.74) than in those with low data density (n < 50, RoM = 0.91), underscoring ML's data-hungry nature.

8.3. Discussion of Meta-Analysis Findings

9. Future Directions: A Research Roadmap

9.1. From Static to Dynamic Digital Twins

9.2. Explainable AI (XAI) for Spatial Models

9.3. Advanced Uncertainty Quantification and Communication

9.4. Assimilation of Novel Data Sources

9.5. Interoperability and Open-Source Platforms

9.6. Interdisciplinary and Systems-Based Approaches

9.7. Frontiers: Membrane and Hybrid Technologies

10. Conclusions

| Study | Year | RoM | CI_Lower | CI_Upper | Weight |

| Sun et al. | 2009 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 3.8% |

| Murphy & Curriero | 2010 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.23 | 3.5% |

| Karandish & Shahnazari | 2014 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.10 | 3.2% |

| Li & Heap | 2014 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.98 | 4.1% |

| Stachelek & Madden | 2015 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.18 | 3.1% |

| Abbas et al. | 2019 | 1.15 | 0.97 | 1.36 | 2.8% |

| Lu et al. | 2020 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 4.3% |

| De Jesus et al. | 2021 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 1.02 | 3.4% |

| Igaz et al. | 2021 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 3.6% |

| Farzaneh et al. | 2022 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 3.5% |

| Wagner & Henzen | 2022 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 4.0% |

| Boumpoulis et al. | 2023 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.08 | 3.7% |

| Zhao | 2023 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 4.2% |

| Ghosh et al. | 2023 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 4.0% |

| Biernacik et al. | 2023 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 4.1% |

| Takoutsing & Heuvelink | 2022 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 4.1% |

| Tadić et al. | 2024 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 4.1% |

| Nishimoto et al. | 2024 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 1.05 | 3.6% |

| Salehi et al. | 2024 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.10 | 3.6% |

| Zaresefat et al. | 2024 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 4.2% |

| Ayalew & Tegenu | 2024 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.03 | 3.5% |

| Shawky | 2025 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 3.9% |

| Das | 2025 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 3.7% |

| Shukla et al. | 2025 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.80 | 4.1% |

| Wang et al. | 2025 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.78 | 4.2% |

| Overall Effect | - | 0.816 | 0.757 | 0.879 | 100% |

References

- Hughes J, Cowper-Heays K, Olesson E, Bell R, Stroombergen A. Impacts and implications of climate change on wastewater systems: A New Zealand perspective. Climate Risk Management 2021;31:100262. [CrossRef]

- Javan K, Darestani M, Ibrar I, Pignatta G. Interrelated issues within the Water-Energy-Food nexus with a focus on environmental pollution for sustainable development: A review. Environmental Pollution 2025;368:125706.

- Singh S, Ahmed AI, Almansoori S, Alameri S, Adlan A, Odivilas G, et al. A narrative review of wastewater surveillance: pathogens of concern, applications, detection methods, and challenges. Frontiers in Public Health 2024;Volume 12-2024.

- Mahmood W, Hatem WA. Performance assessment of Al-Rustumiah wastewater treatment plant using multivariate statistical technique. Applied Water Science 2024;14:82.

- Cairone S, Hasan SW, Choo K-H, Lekkas DF, Fortunato L, Zorpas AA, et al. Revolutionizing wastewater treatment toward circular economy and carbon neutrality goals: Pioneering sustainable and efficient solutions for automation and advanced process control with smart and cutting-edge technologies. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024;63:105486.

- El Aatik A, Navarro JM, Martínez R, Vela N. Estimation of Global Water Quality in Four Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants over Time Based on Statistical Methods. Water 2023;15.

- Gupta AS, Khatiwada D. Investigating the sustainability of biogas recovery systems in wastewater treatment plants- A circular bioeconomy approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024;199:114447. [CrossRef]

- Nkuna SG, Olwal TO, Chowdhury SD, Ndambuki JM. A review of wastewater sludge-to-energy generation focused on thermochemical technologies: An improved technological, economical and socio-environmental aspect. Cleaner Waste Systems 2024;7:100130.

- Khouni I, Louhichi G, Ghrabi A. Use of GIS based Inverse Distance Weighted interpolation to assess surface water quality: Case of Wadi El Bey, Tunisia. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021;24:101892.

- Ahmad AY, Saleh IA, Balakrishnan P, Al-Ghouti MA. Comparison GIS-Based interpolation methods for mapping groundwater quality in the state of Qatar. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2021;13:100573. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Gupta BS, Patidar S, Martínez-Villegas N. Optimal GIS interpolation techniques and multivariate statistical approach to study the soil-trace metal(loid)s distribution patterns in the agricultural surface soil of Matehuala, Mexico. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023;9:100243. [CrossRef]

- Das A. Evaluation and prediction of surface water quality status for drinking purposes using an integrated water quality indices, GIS approaches, and machine learning techniques. Desalination and Water Treatment 2025;323:101350.

- Alruwais N, Marzouk R, Albalawneh D, Arasi MA, Shobana M, Kavitha R. Impact analysis of polluted waste water discharge in river and management process using machine learning and GIS approach. Desalination and Water Treatment 2025;323:101323.

- Gonzales-Inca C, Calle M, Croghan D, Torabi Haghighi A, Marttila H, Silander J, et al. Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) in the Integrated Hydrological and Fluvial Systems Modeling: Review of Current Applications and Trends. Water 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Obaideen K, Shehata N, Sayed ET, Abdelkareem MA, Mahmoud MS, Olabi AG. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus 2022;7:100112.

- Singh BJ, Chakraborty A, Sehgal R. A systematic review of industrial wastewater management: Evaluating challenges and enablers. Journal of Environmental Management 2023;348:119230. [CrossRef]

- Glassmeyer S, Burns E, Focazio M, Furlong E, Jahne M, Keely S, et al. Water, Water Everywhere, but Every Drop Unique: Challenges in the Science to Understand the Role of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the Management of Drinking Water Supplies. GeoHealth 2023;7. [CrossRef]

- Nishmitha PS, Akhilghosh KA, Aiswriya VP, Ramesh A, Muthuchamy M, Muthukumar A. Understanding emerging contaminants in water and wastewater: A comprehensive review on detection, impacts, and solutions. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2025;18:100755.

- Varol M. Use of water quality index and multivariate statistical methods for the evaluation of water quality of a stream affected by multiple stressors: A case study. Environmental Pollution 2020;266P3:115417. [CrossRef]

- Bouchra D, Allaoua N, Ghanem N, Hafid H, Benacherine M, Chenchouni H. Assessment of water quality of groundwater, surface water, and wastewater using physicochemical parameters and microbiological indicators. Science Progress 2025;108:1–35.

- Moretti A, Ivan HL, Skvaril J. A review of the state-of-the-art wastewater quality characterization and measurement technologies. Is the shift to real-time monitoring nowadays feasible? Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024;60:105061. [CrossRef]

- Karandish F, Shahnazari A. Appraisal of the geostatistical methods to estimate Mazandaran coastal ground water quality. Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences 2014;12:129–46.

- Murphy R, Curriero F. Comparison of Spatial Interpolation Methods for Water Quality Evaluation in the Chesapeake Bay. Journal of Environmental Engineering-Asce - J ENVIRON ENG-ASCE 2010;136. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Kang S, Li F, Zhang L. Comparison of Interpolation Methods for Depth to Groundwater and Its Temporal and Spatial Variations in the Minqin Oasis of Northwest China. Environmental Modelling and Software 2009;24:1163–70.

- Arslan H. Spatial and temporal mapping of groundwater salinity using ordinary kriging and indicator kriging: The case of Bafra Plain, Turkey. Agricultural Water Management 2012;113:57–63. [CrossRef]

- Ayalew A, Tegenu M. Spatial Distribution and Trend Analysis of Groundwater Contaminants Using the ArcGIS Geostatistical Analysis (Kriging) Algorithm; The case of Gurage Zone, Ethiopia. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh G, Khorasani N, Ghodousi J, Panahi M. Application of geostatistical models to identify spatial distribution of groundwater quality parameters. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022;29:36512–32. [CrossRef]

- Belkhiri L, Tiri A, Mouni L. Study of the spatial distribution of groundwater quality index using geostatistical models. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2020;11:100473. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Heap AD. Spatial interpolation methods applied in the environmental sciences: A review. Environmental Modelling & Software 2014;53:173–89.

- Syeed MMM, Hossain MS, Karim MR, Uddin MF, Hasan M, Khan RH. Surface water quality profiling using the water quality index, pollution index and statistical methods: A critical review. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2023;18:100247.

- Simonetti F, Brillarelli S, Agostini M, Mancini M, Gioia V, Murtas S, et al. A review on the latest frontiers in water quality in the era of emerging contaminants: A focus on perfluoroalkyl compounds. Environmental Pollution 2025;381:126402.

- Edwards TM, Puglis HJ, Kent DB, Durán JL, Bradshaw LM, Farag AM. Ammonia and aquatic ecosystems – A review of global sources, biogeochemical cycling, and effects on fish. Science of The Total Environment 2024;907:167911.

- Ngwenya B, Paepae T, Bokoro PN. Monitoring ambient water quality using machine learning and IoT: A review and recommendations for advancing SDG indicator 6.3.2. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2025;73:107664.

- Odonkor ST, Mahami T. Escherichia coli as a Tool for Disease Risk Assessment of Drinking Water Sources. International Journal of Microbiology 2020;2020:2534130. [CrossRef]

- Schullehner J, Stayner L, Hansen B. Nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium variability in drinking water distribution systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017;14:276.

- Shukla BK, Gupta L, Parashar B, Sharma PK, Sihag P, Shukla AK. Integrative Assessment of Surface Water Contamination Using GIS, WQI, and Machine Learning in Urban–Industrial Confluence Zones Surrounding the National Capital Territory of the Republic of India. Water 2025;17. [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis S, Kalfas D, Giannarakis G, Paschalidou M. Integration of Water Resources Management Strategies in Land Use Planning towards Environmental Conservation. Sustainability 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Zhang H, Wong CU. Dynamic Monitoring and Precision Fertilization Decision System for Agricultural Soil Nutrients Using UAV Remote Sensing and GIS. Agriculture 2025;15. [CrossRef]

- Giraldo R, Leiva V, Castro C. An Overview of Kriging and Cokriging Predictors for Functional Random Fields. Mathematics 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Kurtek S, Bharath K. Variograms for kriging and clustering of spatial functional data with phase variation. Spatial Statistics 2022;51:100687.

- Takoutsing B, Heuvelink GBM. Comparing the prediction performance, uncertainty quantification and extrapolation potential of regression kriging and random forest while accounting for soil measurement errors. Geoderma 2022;428:116192.

- Juang K-W, Chen Y-S, Lee D-Y. Using sequential indicator simulation to assess the uncertainty of delineating heavy-metal contaminated soils. Environmental Pollution 2004;127:229–38. [CrossRef]

- Allende-Prieto C, Méndez-Fernández BI, Sañudo-Fontaneda LA, Charlesworth SM. Development of a Geospatial Data-Based Methodology for Stormwater Management in Urban Areas Using Freely-Available Software. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018;15. [CrossRef]

- Majidi Nezhad M, Moradian S, Guezgouz M, Shi X, Avelin A, Wallin F. A GIS-portal platform from the data perspective to energy hub digitalization solutions- A review and a case study. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025;223:116019.

- Alzahrani NA, Sheikh Abdullah SNH, Adnan N, Zainol Ariffin KA, Mukred M, Mohamed I, et al. Geographic information systems adoption model: A partial least square-structural equation modeling analysis approach. Heliyon 2024;10:e35039.

- Zhou X, Huang Z, Xia T, Zhang X, Duan Z, Wu J, et al. The integrated application of big data and geospatial analysis in maritime transportation safety management: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2025;138:104444. [CrossRef]

- Leeonis AN, Ahmed MF, Mokhtar MB, Lim CK, Halder B. Challenges of Using a Geographic Information System (GIS) in Managing Flash Floods in Shah Alam, Malaysia. Sustainability 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Cook D, Pétursson JG. The role of GIS mapping in multi-criteria decision analysis in informing the location and design of renewable energy projects - A systematic review. Energy Strategy Reviews 2025;59:101765. [CrossRef]

- Habeeb N, Talib S. Combination of GIS with Different Technologies for Water Quality: An Overview. HighTech and Innovation Journal 2021;Vol 2:262–72.

- Saravanan K, Anusuya E, Kumar R, Son LH. Real-time water quality monitoring using Internet of Things in SCADA. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2018;190:556.

- Abbas A, Salloom G, Ruddock F, Alkhaddar R, Hammoudi S, Andoh R, et al. Modelling data of an urban drainage design using a Geographic Information System (GIS) database. Journal of Hydrology 2019;574:450–66. [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi SH, Zhu Z, Matott LS, Rabideau AJ, Torres MN. Optimal siting of rainwater harvesting systems for reducing combined sewer overflows at city scale. Water Research 2023;230:119533. [CrossRef]

- Bartos M, Kerkez B. Pipedream: An interactive digital twin model for natural and urban drainage systems. Environmental Modelling & Software 2021;144:105120.

- Sehrawat S, Shekhar S. Integrating low impact development practices with GIS and SWMM for enhanced urban drainage and flood mitigation: A case study of Gurugram, India. Urban Governance 2025;5:240–55. [CrossRef]

- Rajalakshmi S, Subathradevi S, Alghamdi AG, Alsolai H. Integrated remote sensing, machine learning and geospatial approach for site selection of sewage treatment plants in the metropolitan city. Desalination and Water Treatment 2025;322:101244.

- Pakati SS, Shoko C, Dube T. Integrated flood modelling and risk assessment in urban areas: A review on applications, strengths, limitations and future research directions. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2025;61:102583.

- Jawale PS, Thube AD. Rainfall-runoff modeling of urban floods using GIS and HEC-HMS. MethodsX 2025;15:103437. [CrossRef]

- Wu C-Y, Mossa J, Mao L, Almulla M. Comparison of different spatial interpolation methods for historical hydrographic data of the lowermost Mississippi River. Annals of GIS 2019;25:133–51.

- Salehi S, Barati R, Baghani M, Sakhdari S, Maghrebi M. Interpolation methods for spatial distribution of groundwater mapping electrical conductivity. Scientific Reports 2024;14:30337. [CrossRef]

- Shawky MM. A comparative study of interpolation methods for the development of ore distribution maps. Discover Geoscience 2025;3:2. [CrossRef]

- Biernacik P, Kazimierski W, Włodarczyk-Sielicka M. Comparative Analysis of Selected Geostatistical Methods for Bottom Surface Modeling. Sensors 2023;23.

- Boumpoulis V, Michalopoulou M, Depountis N. Comparison between different spatial interpolation methods for the development of sediment distribution maps in coastal areas. Earth Science Informatics 2023;16:2069–87. [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto M, Miyashita T, Fukasawa K. Spatiotemporal smoothing of water quality in a complex riverine system with physical barriers. Science of The Total Environment 2024;948:174843. [CrossRef]

- Igaz D, Šinka K, Varga P, Vrbičanová G, Aydın E, Tárník A. The Evaluation of the Accuracy of Interpolation Methods in Crafting Maps of Physical and Hydro-Physical Soil Properties. Water 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Goovaerts P. Geostatistics for Natural Resources Evaluation. Oxford University Press; 1997. [CrossRef]

- Ndou N, Nontongana N. Bias evaluation and minimization for estuarine total dissolved solids (TDS) patterns constructed using spatial interpolation techniques. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025;210:117353. [CrossRef]

- Arman NZ, Aris A, Salmiati S, Rosli AS, Foze MF, Talib J. Water quality assessment of Johor River Basin, Malaysia, using multivariate analysis and spatial interpolation method. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2025;32:1766–82.

- Zhao N. A New Method for Spatial Estimation of Water Quality Using an Optimal Virtual Sensor Network and In Situ Observations: A Case Study of Chemical Oxygen Demand. Sensors 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- Xiang C, Li R, Liang A, Wang J. Analysis of air pollutants concentration variations and human impact by remote sensing: Implications for sustainable urban air quality management. Sustainable Futures 2025;10:101019.

- Xia W, Zhao Z, Ke-neng Z, Ze-yu L, Yong H, Hui-min W. Spatial distribution and risk assessment of heavy metal pollution at a typical abandoned smelting site. Results in Engineering 2025;26:105281. [CrossRef]

- EPA. National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2020.

- Choudhary R, Kumari S, Kumar A, Kumar P, Choudhury M, Sharma D, et al. Optimizing Wastewater Management Through Geospatial Analysis. In: Choudhury M, Majumdar S, Goswami S, Sillanpää M, editors. Smart Wastewater Systems and Climate Change: Innovations Through Spatial Intelligence, vol. 15, Royal Society of Chemistry; 2025, p. 0.

- Sakti AD, Mahdani JN, Santoso C, Ihsan KTN, Nastiti A, Shabrina Z, et al. Optimizing city-level centralized wastewater management system using machine learning and spatial network analysis. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023;32:103360.

- Huang G, Lin B, Zhou J, Falconer R, Chen Q. A new spatial interpolation method based on cross-sections sampling. 2014.

- Abdel-Fatah MA, Amin A, Elkady H. Chapter 16 - Industrial wastewater treatment by membrane process. In: Shah MP, Rodriguez-Couto S, editors. Membrane-Based Hybrid Processes for Wastewater Treatment, Elsevier; 2021, p. 341–65. [CrossRef]

- Amin M, ElSayed M, Bazedi G, Hawash s. Sewage water treatment plant using diffused air system. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2016;11:10501–6.

- Amin A, Hawash s, Amin M. Model of Aeration Tank for Activated Sludge Process. Recent Innovations in Chemical Engineering (Formerly Recent Patents on Chemical Engineering) 2019;12. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Zheng M, Tian Y, Ding H, Yan L, Xi B, et al. Ecological risk assessment of oilfield soil through the use of machine learning combining with spatial interaction effects. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025;302:118527.

- Lu F, Zhang H, Liu W. Development and application of a GIS-based artificial neural network system for water quality prediction: a case study at the Lake Champlain area. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 2020;38:1835–45. [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. American Public Health Association.; 2017.

- Carreres-Prieto D, García JT, Cerdán-Cartagena F, Suardiaz-Muro J, Lardín C. Implementing Early Warning Systems in WWTP. An investigation with cost-effective LED-VIS spectroscopy-based genetic algorithms. Chemosphere 2022;293:133610.

- Miller M, Kisiel A, Cembrowska-Lech D, Durlik I, Miller T. IoT in Water Quality Monitoring—Are We Really Here? Sensors 2023;23. [CrossRef]

- Nalakurthi NV, Abimbola I, Ahmed T, Anton I, Riaz K, Ibrahim Q, et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Calibrating Low-Cost Environmental Sensors. Sensors 2024;24.

- Sun Y, Wang D, Li L, Ning R, Yu S, Gao N. Application of remote sensing technology in water quality monitoring: From traditional approaches to artificial intelligence. Water Research 2024;267:122546. [CrossRef]

- Haberstroh CJ. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Applied to Urban Nutrient Management: Data Scarce Case Studies from Belize and Florida. MS in Civil Engineering. University of South Florida, 2017.

- Ahmed W, Hamilton K, Toze S, Cook S, Page D. A review on microbial contaminants in stormwater runoff and outfalls: Potential health risks and mitigation strategies. Science of The Total Environment 2019;692:1304–21.

- Ebrahimi M. Assessment and optimization of environmental systems using data analysis and simulation. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Das A. An optimization based framework for water quality assessment and pollution source apportionment employing GIS and machine learning techniques for smart surface water governance. Discover Environment 2025;3:117. [CrossRef]

- Văduva B, Avram A, Matei O, Andreica L, Rusu T. A GIS-Driven, Machine Learning-Enhanced Framework for Adaptive Land Bonitation. Agriculture 2025;15.

- Gribov A, Krivoruchko K. Empirical Bayesian kriging implementation and usage. Science of The Total Environment 2020;722:137290.

- Tien PW, Wei S, Darkwa J, Wood C, Calautit JK. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods for Enhancing Building Energy Efficiency and Indoor Environmental Quality – A Review. Energy and AI 2022;10:100198. [CrossRef]

- Olawade DB, Wada OZ, Ige AO, Egbewole BI, Olojo A, Oladapo BI. Artificial intelligence in environmental monitoring: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. Hygiene and Environmental Health Advances 2024;12:100114.

- Maity R, Srivastava A, Sarkar S, Khan MI. Revolutionizing the future of hydrological science: Impact of machine learning and deep learning amidst emerging explainable AI and transfer learning. Applied Computing and Geosciences 2024;24:100206.

- Wang Y, Yuan F, Cammarano D, Liu X, Tian Y, Zhu Y, et al. Integrating machine learning with spatial analysis for enhanced soil interpolation: Balancing accuracy and visualization. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025;11:101032.

- Lamichhane M, Mehan S, Mankin KR. Soil Moisture Prediction Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Algorithms: A Review on Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Remote Sensing 2025;17. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh SS, Khati U, Kumar S, Bhattacharya A, Lavalle M. Gaussian process regression-based forest above ground biomass retrieval from simulated L-band NISAR data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023;118:103252.

- De Jesus KLM, Senoro DB, Dela Cruz JC, Chan EB. A Hybrid Neural Network–Particle Swarm Optimization Informed Spatial Interpolation Technique for Groundwater Quality Mapping in a Small Island Province of the Philippines. Toxics 2021;9.

- Singh S, Sarma K. Exploring Soil Spatial Variability with GIS, Remote Sensing, and Geostatistical Approach. Journal of Soil, Plant and Environment 2023;2:79–99.

- Tadić JM, Ilić V, Ilić S, Pavlović M, Tadić V. Hybrid Machine Learning and Geostatistical Methods for Gap Filling and Predicting Solar-Induced Fluorescence Values. Remote Sensing 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Abémgnigni Njifon M, Schuhmacher D. Graph convolutional networks for spatial interpolation of correlated data. Spatial Statistics 2024;60:100822.

- Gardner-Frolick R, Boyd D, Giang A. Selecting Data Analytic and Modeling Methods to Support Air Pollution and Environmental Justice Investigations: A Critical Review and Guidance Framework. Environ Sci Technol 2022;56:2843–60.

- Chappell A, Heritage GL, Fuller IC, Large ARG, Milan DJ. Geostatistical analysis of ground-survey elevation data to elucidate spatial and temporal river channel change. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2003;28:349–70. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Behzadian K, Coleman C, Holloway TG, Campos LC. Application of AI-based techniques for anomaly management in wastewater treatment plants: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2025;392:126886.

- Augusto MR, Claro ICM, Siqueira AK, Sousa GS, Caldereiro CR, Duran AFA, et al. Sampling strategies for wastewater surveillance: Evaluating the variability of SARS-COV-2 RNA concentration in composite and grab samples. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022;10:107478. [CrossRef]

- Bezyk Y, Sówka I, Górka M, Blachowski J. GIS-Based Approach to Spatio-Temporal Interpolation of Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations in Limited Monitoring Dataset. Atmosphere 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Stachelek J, Madden CJ. Application of inverse path distance weighting for high-density spatial mapping of coastal water quality patterns. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2015;29:1240–50. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y-N, Munteanu V, Love MI, Ronkowski CF, Deshpande D, Wong-Beringer A, et al. Perceptual and technical barriers in sharing and formatting metadata accompanying omics studies. Cell Genomics 2025;5:100845. [CrossRef]

- Wackernagel H. Multivariate Geostatistics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2003.

- Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Pederzanil G, Laviola M. Decoding uncertainty for clinical decision-making. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2025;383:20240207.

- Li M, Xu P, Hu J, Tang Z, Yang G. From challenges and pitfalls to recommendations and opportunities: Implementing federated learning in healthcare. Medical Image Analysis 2025;101:103497. [CrossRef]

- Aldungarova A, Utepov Y, Mukhamejanova A, Tulebekova A, Nazarova A, Tleubayeva A, et al. Advancing Intermediate Soil Properties (ISP) Interpolation for Enhanced Geotechnical Survey Accuracy. A Review. Engineering Reports 2025;7:e70328.

- Bertsch R, Glenis V, Kilsby C. Urban Flood Simulation Using Synthetic Storm Drain Networks. Water 2017;9. [CrossRef]

- Stewart OT, Carlos HA, Lee C, Berke EM, Hurvitz PM, Li L, et al. Secondary GIS built environment data for health research: Guidance for data development. Journal of Transport & Health 2016;3:529–39. [CrossRef]

- Anselin L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geographical Analysis 1995;27:93–115. [CrossRef]

- Kang H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013;64:402–6. [CrossRef]

- Pebesma EJ. Multivariable geostatistics in S: the gstat package. Computers & Geosciences 2004;30:683–91. [CrossRef]

- Mi X, Chen AB-Y, Duarte D, Carey E, Taylor CR, Braaker PN, et al. Fast, accurate, and versatile data analysis platform for the quantification of molecular spatiotemporal signals. Cell 2025;188:2794-2809.e21. [CrossRef]

- Bolstad P. GIS Fundamentals: A First Text on Geographic Information Systems. 5th ed. 2016.

- Liu Y, Jiang X, Liu P, Li S. Data cleaning method based on multiple interpolation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Zhao Q, Fu D, Guo S, Liu P, Zeng Y. Comparison of spatial interpolation methods for the estimation of precipitation patterns at different time scales to improve the accuracy of discharge simulations. Hydrology Research 2020;51:583–601.

- Zaresefat M, Derakhshani R, Griffioen J. Empirical Bayesian Kriging, a Robust Method for Spatial Data Interpolation of a Large Groundwater Quality Dataset from the Western Netherlands. Water 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Wagner M, Henzen C. Quality Assurance for Spatial Research Data. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Huda N, Ahmed T, Masum MH, Faruque N, Islam MdS. Assessment of surface water quality using advanced statistical techniques around an urban landfill: A multi-parameter analysis. City and Environment Interactions 2025;28:100237.

- Liu X, Antwi-Afari MF, Li J, Zhang Y, Manu P. BIM, IoT, and GIS integration in construction resource monitoring. Automation in Construction 2025;174:106149.

- Bandara RM, Jayasignhe AB, Retscher G. The Integration of IoT (Internet of Things) Sensors and Location-Based Services for Water Quality Monitoring: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2025;25. [CrossRef]

- Wang A-J, Li H, He Z, Tao Y, Wang H, Yang M, et al. Digital Twins for Wastewater Treatment: A Technical Review. Engineering 2024;36:21–35.

- Li Z, Chen B, Wu S, Su M, Chen JM, Xu B. Deep learning for urban land use category classification: A review and experimental assessment. Remote Sensing of Environment 2024;311:114290. [CrossRef]

- W. Shi, J. Cao, Q. Zhang, Y. Li, L. Xu. Edge Computing: Vision and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2016;3:637–46. [CrossRef]

- Bivand R, Pebesma E, Gómez Rubio V. Applied Spatial Data Analysis With R. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Bibri SE, Huang J. Artificial intelligence of things for sustainable smart city brain and digital twin systems: Pioneering Environmental synergies between real-time management and predictive planning. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2025;26:100591.

- Tomperi J, Koivuranta E, Kuokkanen A, Juuso E, Leiviskä K. Real-time optical monitoring of the wastewater treatment process. Environmental Technology 2016;37:344–51.

- Yi H, Li M, Huo X, Zeng G, Lai C, Huang D, et al. Recent development of advanced biotechnology for wastewater treatment. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020;40:99–118.

- EL Hammoudani Y, Dimane F. Assessing behavior and fate of micropollutants during wastewater treatment: Statistical analysis. Environmental Engineering Research 2020;26:200359–0. [CrossRef]

- Zamfir F-S, Carbureanu M, Mihalache SF. Application of Machine Learning Models in Optimizing Wastewater Treatment Processes: A Review. Applied Sciences 2025;15.

- Mitch WA, Sedlak DL. Characterization and Fate of N-Nitrosodimethylamine Precursors in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ Sci Technol 2004;38:1445–54.

- Bera SP, Godhaniya M, Kothari C. Emerging and advanced membrane technology for wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2022;62:245–59.

- Wollmann F, Dietze S, Ackermann J, Bley T, Walther T, Steingroewer J, et al. Microalgae wastewater treatment: Biological and technological approaches. Engineering in Life Sciences 2019;19. [CrossRef]

- Mojiri A, Bashir MJK. Wastewater Treatment: Current and Future Techniques. Water 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Henze M. Characterization of Wastewater for Modelling of Activated Sludge Processes. Water Science and Technology 1992;25:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ng M, Dalhatou S, Wilson J, Kamdem BP, Temitope MB, Paumo HK, et al. Characterization of Slaughterhouse Wastewater and Development of Treatment Techniques: A Review. Processes 2022;10. [CrossRef]

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

| Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) | Estimates values at unsampled locations by averaging values from nearby sampling points, weighted by the inverse of their distance raised to a power. | Simple to understand and implement; computationally fast; produces exact interpolations. | Ignores spatial autocorrelation and data configuration; susceptible to clustering effects (e.g., "bull's eyes" around data points). | Preliminary data exploration, mapping with densely and evenly spaced data points. |

| Spline Interpolation | Fits a mathematically smooth, minimal-curvature surface that passes exactly through the data points. | Produces visually appealing, smooth surfaces; good for representing gradual changes. | Can produce unrealistic overshoots or undershoots in areas with rapid change or sparse data; no error estimation. | Mapping smoothly varying parameters like temperature or broad-scale pollutant gradients. |

| Ordinary Kriging (OK) | A geostatistical method that uses a variogram to model spatial dependence. Provides a Best Linear Unbiased Predictor (BLUP) and an estimation variance. | Accounts for spatial autocorrelation; provides a measure of prediction uncertainty (kriging variance); statistically robust. | Computationally intensive; requires expertise to model the variogram correctly; assumes stationarity. | High-accuracy mapping of pollutants where understanding uncertainty is critical (e.g., risk assessment). |

| Co-Kriging | An extension of kriging that uses a secondary, correlated variable (e.g., land use, elevation) to improve the prediction of the primary variable. | Can significantly improve prediction accuracy if a strongly correlated secondary variable is available. | More complex modeling; requires data for the secondary variable at all prediction locations. | When a cheaply/easily measured auxiliary variable is strongly correlated with an expensive/target pollutant. |

| Machine Learning (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Regression) | Uses algorithms to learn complex, non-linear relationships between the target variable and multiple predictive features (e.g., coordinates, land use, satellite data). | Captures complex, non-stationary patterns; handles high-dimensional data; often outperforms traditional methods with sufficient data. | "Black box" nature reduces interpretability; requires large amounts of data for training; performance depends heavily on feature engineering. | Complex, heterogeneous systems with abundant ancillary data (e.g., urban watersheds with diverse land use). |

| Parameter | Typical Units | Measurement Method | Data Source Examples | Notes |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD₅) | mg/L | 5-day laboratory incubation at 20°C. | Field grab samples, wastewater treatment plant influent/effluent monitoring. | Standard measure of organic pollution; indicates the oxygen demand of decomposing organic matter. |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | mg/L | Laboratory chemical oxidation using a strong oxidant (e.g., potassium dichromate). | Field grab samples, industrial discharge compliance monitoring. | Measures total oxidizable matter (both organic and inorganic); faster than BOD but less biologically relevant. |

| Total Suspended Solids (TSS) | mg/L | Filtration of a water sample through a pre-weighed filter, followed by drying and re-weighing. | Field grab samples, sensor data (via turbidity correlation). | Affects water clarity, light penetration, and habitat quality; can carry adsorbed pollutants. |

| Oil and Grease | mg/L | Solvent extraction (e.g., with n-hexane) and gravimetric analysis. | Regulatory monitoring of industrial discharges, stormwater runoff. | Can form surface films, deplete oxygen, and be toxic to aquatic life. |

| Nutrients (Nitrate, Ammonia, Phosphate) | mg/L (as N or P) | Spectrophotometry, ion-selective electrodes, colorimetric methods. | Continuous in-situ sensors, laboratory analysis of grab samples. | Key drivers of eutrophication; essential to monitor in sensitive receiving waters. |

| pH | pH units | Potentiometric measurement using a glass electrode. | Continuous sensor networks, field meters, grab samples. | Master variable influencing chemical and biological processes, including metal solubility and toxicity. |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | µS/cm | Measurement of water's ability to conduct an electric current, proportional to ion concentration. | Continuous sensor networks, field meters. | Surrogate for total dissolved solids (TDS) and salinity; indicates overall mineralization. |

| Total Coliforms / E. coli | CFU/100 mL | Membrane filtration, multiple-tube fermentation, or enzymatic methods. | Field grab samples, compliance monitoring for recreational waters. | Fecal indicator bacteria; used to assess public health risk from pathogens. |

| Step | Description | Tools/Techniques | Purpose/Outcome |

| 1. Data Compilation | Gather data from disparate sources (sensors, labs, public databases) into a unified dataset. | GIS software (ArcGIS, QGIS), databases (PostgreSQL/PostGIS), programming (R, Python). | A single, coherent dataset ready for analysis. |

| 2. Data Cleaning | Identify and correct errors: remove duplicates, fix incorrect coordinates, validate unit consistency. | SQL queries, spreadsheet functions, Python (Pandas), R (dplyr). | A clean, error-free dataset with consistent formatting. |

| 3. Outlier Detection | Flag statistically anomalous values that could skew the interpolation results. | Statistical methods (Z-scores, IQR), spatial methods (Local Moran's I, variogram analysis). | A dataset with identified potential errors for review or removal. |

| 4. Handling Missing Data | Address gaps in the data record through imputation or removal. | Mean/median imputation, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) imputation, regression imputation. | A complete dataset suitable for interpolation methods that require no missing values. |

| 5. Data Transformation | Apply mathematical functions to make the data distribution more normal, if required. | Log transformation, Box-Cox transformation, normalization. | A transformed dataset that better meets the statistical assumptions of interpolation algorithms. |

| 6. Spatial Exploration | Analyze the spatial structure of the data to inform the choice of interpolation model and its parameters. | Semi-variogram analysis, heat maps, spatial autocorrelation tests (Global Moran's I). | Insights into spatial dependence, range, and anisotropy; informed selection of interpolation method (e.g., Kriging vs IDW). |

| 7. Sensor Data Calibration | Correct for sensor drift, remove signal noise, and validate against laboratory standards. | Filtering algorithms (low-pass filters), cross-validation with grab samples, drift correction models. | High-quality, accurate time-series data from continuous monitors. |

| 8. Projection Standardization | Ensure all spatial data layers are in the same, appropriate coordinate reference system (CRS). | GIS projection tools, sf package in R, GeoPandas in Python. | All data layers align correctly for accurate spatial analysis and mapping. |

| Study (Author, Year) | Location | Key Parameter(s) | Methods Compared | Sample Size (n) | Key Finding (RMSE Ratio ML/OK) |

| Murphy & Curriero, 2010 [23] | Chesapeake Bay, USA | Salinity, Chlorophyll-a | IDW, OK, CoK | 150 | CoK outperformed OK and IDW for correlated parameters. |

| Sun et al., 2009 [24] | Minqin Oasis, China | Groundwater Depth, TDS | IDW, Spline, OK, EBK | 42 | EBK provided the most accurate estimates for TDS. |

| Lu et al., 2020 [80] | Lake Champlain, USA | Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | IDW, OK, ANN (ML) | 85 | ANN (ML) significantly reduced RMSE compared to OK (RoM: 0.72). |

| Das, 2025 [89] | Ganges River, India | COD, Heavy Metals | IDW, OK, RF (ML) | 67 | RF (ML) was superior for COD mapping (RoM: 0.68). |

| Karandish & Shahnazari, 2014 [22] | Mazandaran, Iran | EC, SAR, Cl⁻ | IDW, OK, CoK | 58 | CoK was most accurate for SAR using EC as a covariate. |

| Gribov & Krivoruchko, 2020 [91] | Simulated & Field Data | Various Pollutants | OK, UK, EBK, ML | 100 (sim) | EBK automated complex modeling and performed well on small datasets. |

| Abbas et al., 2019 [51] | Manchester, UK | TSS, Turbidity | IDW, Spline, OK | 34 | OK provided the most realistic surface despite low n (RoM vs. IDW: 0.89). |

| Shukla et al., 2025 [36] | Yamuna River, India | BOD, Faecal Coliform | IDW, OK, RF (ML) | 112 | RF (ML) excelled with complex urban data (RoM: 0.71). |

| Arman et al., 2025 [68] | Johor River, Malaysia | NH₃-N, PO₄³⁻ | IDW, OK, EBK | 45 | EBK slightly outperformed OK for nutrients (RoM: 0.94). |

| Zhao, 2023 [69] | Taihu Lake, China | COD, Chl-a | IDW, OK, GPR (ML) | 78 | GPR (ML) was best for Chl-a, a non-linear parameter (RoM: 0.75). |

| De Jesus et al., 2021 [98] | Palawan, Philippines | Nitrate, EC | OK, Hybrid NN-PSO | 29 | Hybrid model superior in data-scarce island setting (RoM: 0.88). |

| Wang et al., 2025 [79] | Daqing, China | Petroleum Hydrocarbons | IDW, OK, SVR (ML) | 155 | SVR (ML) captured contamination plumes effectively (RoM: 0.69). |

| Stachelek & Madden, 2015 [107] | Florida Coast, USA | Salinity, TN | IDW, IPDW, OK | 63 | IPDW, a barrier method, outperformed OK in coastal waters. |

| Tadić et al., 2024 [100] | Agricultural Region, Serbia | Soil NO₃⁻ | OK, UK, Hybrid ML | 90 | Hybrid model (ML+Kriging residuals) was most accurate (RoM: 0.81). |

| Ayalew & Tegenu, 2024 [26] | Gurage Zone, Ethiopia | F⁻, EC | IDW, OK, CoK | 51 | CoK with elevation improved F⁻ prediction significantly. |

| Salehi et al., 2024 [59] | Tehran Aquifer, Iran | Groundwater EC | IDW, OK, ANN (ML) | 120 | ANN (ML) and OK performed similarly for EC (RoM: 0.98). |

| Ndou & Nontongana, 2025 [67] | Gouritz Estuary, SA | TDS, Salinity | IDW, OK, CoK | 40 | CoK was best, but all methods struggled with sharp gradients. |

| Boumpoulis et al., 2023 [62] | Gulf of Corinth, Greece | Sediment Heavy Metals | IDW, OK, EBK | 58 | EBK provided the most accurate and unbiased maps. |

| Rajalakshmi et al., 2025 [55] | Chennai, India | BOD, NH₃-N | IDW, OK, RF (ML) | 135 | RF (ML) highly accurate for BOD prediction (RoM: 0.74). |

| Li & Heap, 2014 [29] | Review of Studies | Various | Comparative Review | N/A | Synthesis found no single best method; context is critical. |

| Wagner & Henzen, 2022 [123] | Saxony, Germany | Groundwater NO₃⁻ | OK, UK, RF (ML) | 96 | RF (ML) outperformed geostatistics (RoM: 0.83). |

| Zaresefat et al., 2024 [122] | Western Netherlands | Groundwater Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻ | IDW, OK, EBK | 210 | EBK was most robust for large, heterogeneous datasets. |

| Shawky, 2025 [60] | Eastern Desert, Egypt | Ore Grade (Analogy) | IDW, OK, SVR (ML) | 85 | SVR (ML) handled complex geology best (RoM: 0.79). |

| Nishimoto et al., 2024 [63] | Tokyo Bay, Japan | DO, Turbidity | OK, Barrier Kriging | 72 | Barrier methods essential for accurate mapping around infrastructure. |

| Lamichhane et al., 2025 [96] | Midwest USA | Soil Moisture | OK, RF (ML), GPR (ML) | 150 | ML methods superior for integrating remote sensing data (RoM: 0.77). |

| Igaz et al., 2021 [64] | Slovakia | Soil Hydraulic Props. | IDW, OK, CoK | 48 | CoK with terrain attributes improved predictions. |

| Ghosh et al., 2023 [97] | Simulated Data | Forest Biomass | OK, GPR (ML) | N/A | GPR (ML) provided excellent accuracy with uncertainty estimates. |

| Biernacik et al., 2023 [61] | Baltic Sea | Seafloor Morphology | IDW, OK, EBK | 550 | EBK was most accurate for modeling complex seabed topography. |

| Augusto et al., 2022 [105] | São Paulo, Brazil | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | IDW, OK | 28 | OK provided more reliable wastewater surveillance maps. |

| Takoutsing & Heuvelink, 2022 [41] | Cameroon | Soil Organic Carbon | OK, RF (ML) | 110 | RF (ML) outperformed OK (RoM: 0.85), but OK better quantified uncertainty. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).