Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. EFA Results

3.2. Total Variance Explained

3.3. Adjustment Indices

3.4. Relationship Between Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAZ | Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas (Autonomous University of Zacatecas) |

| PSAS | Psychometric Selfie Addiction Scale |

| NPI-40 | Narcissistic Personality Inventory |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardised Root Mean Square Residual |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

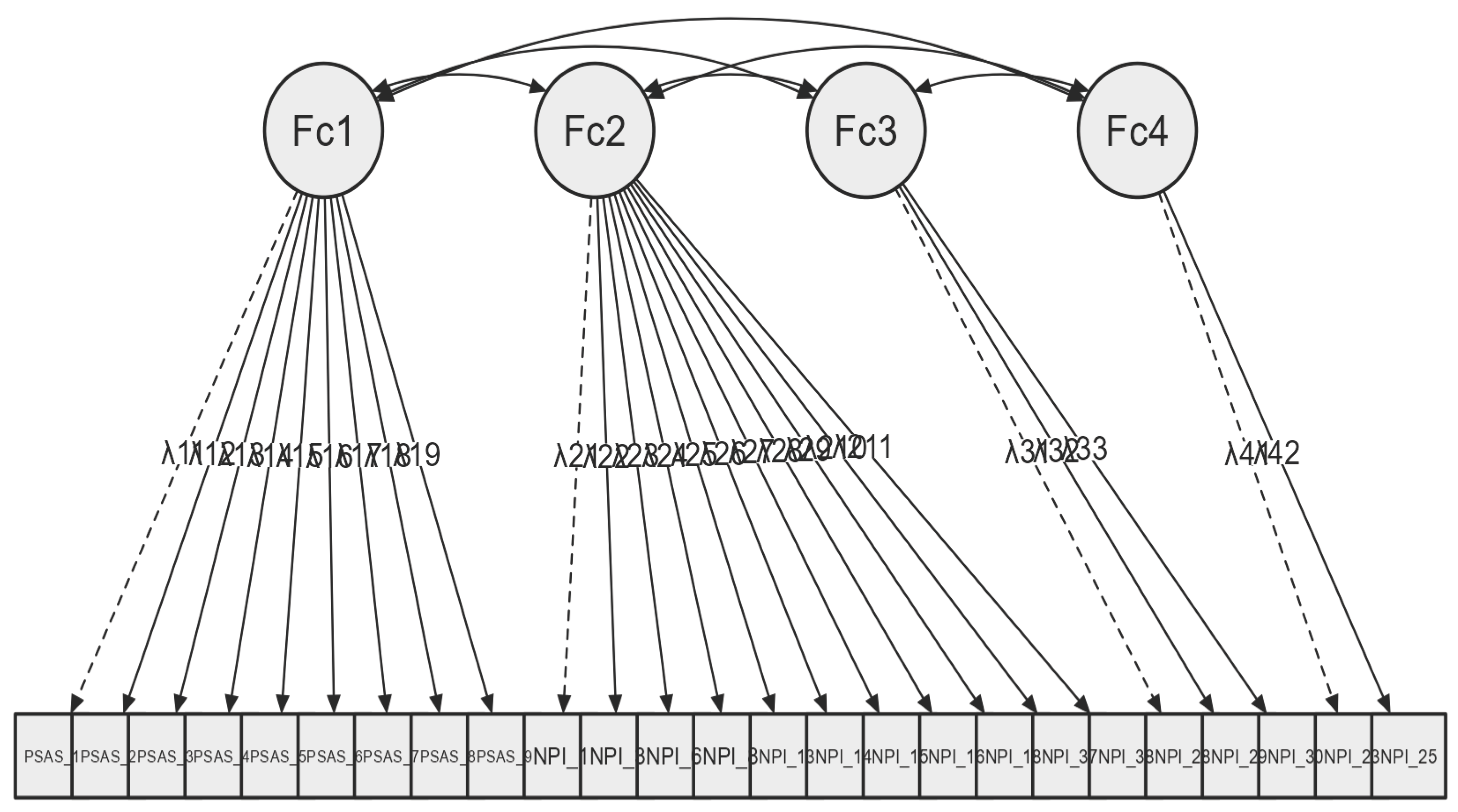

| Fc1 | Factor 1 |

| Fc2 | Factor 2 |

| Fc3 | Factor 3 |

| Fc4 | Factor 4 |

References

- Aguilo, V., Gerente, A., & Marasigan, P. (2022). Selfie-taking Behavior and Narcissistic Tendencies of College Students. International Review of Social Sciences Research, 2(2), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I., Tak, P., & Shekhawat, H. (2023). The moderating role of exhibitionism in the relationship between psychological needs and selfie-posting behavior. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3610-3616. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, B., & Nagalingam, S. (2015). Validation of Psychometric Scale on Selfie Addition. International Journal of Contemporary Medical Research, 2(4), 941-946. [CrossRef]

- Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría. (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5®), (Quinta). Editorial Médica Panamericana. https://www.federaciocatalanatdah.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/dsm5-manualdiagnsticoyestadisticodelostrastornosmentales-161006005112.pdf.

- Barelds, D. P. H., & Dijkstra, P. (2010). Narcissistic Personality Inventory: Structure of the adapted Dutch version. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(2), 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Beos, N., Kemps, E., & Prichard, I. (2025). Relationships between social media, body image, physical activity, and anabolic-androgenic steroid use in men: A systematic review. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 26(1), 105-128. [CrossRef]

- Boggero, A., Puente, G. D., & Bragazzi, N. L. (2022). Selfie takers are Nomophobic? A Correlational Study Between Selfie Addiction, Nomophobia, Locus of Control and Validation of Selfie-Liking Scale in Italian Language. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 42(3), 33752-33761. [CrossRef]

- Boursier, V., Gioia, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Selfie-engagement on social media: Pathological narcissism, positive expectation, and body objectification – Which is more influential? Addictive Behaviors Reports, 11, 100263. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research: Second Edition (Second, Vol. 1). Guilford Press. https://www.guilford.com/books/Confirmatory-Factor-Analysis-for-Applied-Research/Timothy-Brown/9781462515363.

- Buffardi, L. E., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Narcissism and Social Networking Web Sites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(10), 1303-1314. [CrossRef]

- Casale, S., & Banchi, V. (2020). Narcissism and problematic social media use: A systematic literature review. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 11, 100252. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2024). How Do Social Media Affect Social Appearance Anxiety of Chinese High School Students—Take Little Red Book for an Example. Communications in Humanities Research, 38, 144-152. [CrossRef]

- Cornell, S., Brander, R., & Peden, A. (2023). Selfie-Related Incidents: Narrative Review and Media Content Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25(1), e47202. [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Di Pomponio, I., & Cerniglia, L. (2024). Exploring the Mental Health Frontier: Social Media, the Metaverse and Their Impact on Psychological Well-Being. Adolescents, 4(2), 226-230. [CrossRef]

- Fam, J. Y. (2024). Why selfie? Gender invariance in motives for taking and posting selfies. Psychological Thought, 17(2), 359-373. [CrossRef]

- Fidan, M., Debbağ, M., & Fidan, B. (2021). Adolescents Like Instagram! From Secret Dangers to an Educational Model by its Use Motives and Features: An Analysis of Their Mind Maps. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(4), 501-531. [CrossRef]

- Fs, A., Mia, A. K., & F, D. (2021). A Systematic Review of Immersive Social Media Activities and Risk Factors for Sexual Boundary Violations among Adolescents. IIUM Medical Journal Malaysia, 20(1), 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F., McLean, S., Griffiths, M. D., & Boursier, V. (2023). Adolescents’ selfie-taking and selfie-editing: A revision of the photo manipulation scale and a moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3460-3476. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis (Octava). Cengage Learning, EMEA. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://eli.johogo.com/Class/CCU/SEM/_Multivariate%20Data%20Analysis_Hair.pdf.

- Henson, R. K., & Roberts, J. K. (2006). Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Published Research: Common Errors and Some Comment on Improved Practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(3), 393-416. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-C., Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K. S., Chang, Y.-L., Hung, C.-H., Chen, J.-S., Lee, K.-H., & Lin, C.-Y. (2023). Associations between social media addiction, psychological distress, and food addiction among Taiwanese university students. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Lu, A., Lin, Y., Liu, S., Li, J., Song, T., Li, C., Huang, X., Wang, X., Luo, J., Ye, L., Jian, Y., & Zhong, W. (2023). Fear of missing out as a mediator and social capital as a moderator of the relationship between the narcissism and the social media use among adolescents. Psihologija, 56(4), 451-474. [CrossRef]

- Juárez Velarde, M. F., & Valdez, E. A. (2024). Adaptación y validación de una escala de actitudes incluyentes hacia personas trans en Sonora. Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, 12(26), Article 26. [CrossRef]

- Legkauskas, V., & Kudlaitė, U. (2022). Gender Differences in Links between Daily Use of Instagram and Body Dissatisfaction in a Sample of Young Adults in Lithuania. Psihologijske Teme, 31(3), 709-719. [CrossRef]

- Leota, J., Faulkner, P., Mazidi, S., Simpson, D., & Nash, K. (2024). Neural rhythms of narcissism: Facets of narcissism are associated with different neural sources in resting-state EEG. European Journal of Neuroscience, 60(5), 4907-4921. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B., Wu, A. M. S., Feng, L.-F., Deng, Y., Li, J.-H., Chen, Y.-X., Mai, J.-C., Mo, P. K. H., & Lau, J. T. F. (2020). Classification of probable online social networking addiction: A latent profile analysis from a large-scale survey among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(3), 698-708. [CrossRef]

- Martingano, A. J., Konrath, S., Zarins, S., & Okaomee, A. A. (2022). Empathy, narcissism, alexithymia, and social media use. Psychology of Popular Media, 11(4), 413-422. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64-82. [CrossRef]

- Mosanya, M., Uram, P., & Kocur, D. J. (2024). Social media: Does it always hurt? Self-compassion and narcissism as mediators of social media’s predicting effect on self-esteem and body image and gender effect: A study on a Polish community sample. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 55, 11-55. [CrossRef]

- Mubeen, B., Ashraf, M., & Ikhlaq, S. (2022). Selfie Addiction and Narcissism as Correlates and Predictors of Psychological Well-being among Young Adults. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 16(3), 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K. I., Abdullah, Z. D., Abdulrahman, R. O., & Ismail, A. A. (2021). Factors Underlie Selfie Addiction: Developing and Validating a Scale. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 7(1), 82-92. [CrossRef]

- Nagalingam, S., Arumugam, B., & Preethy, S. P. T. (2019). Selfie addiction: The prodigious self-portraits. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 7(3), 694-698. [CrossRef]

- Nash, K., Johansson, A., & Yogeeswaran, K. (2019). Social Media Approval Reduces Emotional Arousal for People High in Narcissism: Electrophysiological Evidence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00292.

- Nasir A., J., & Azhar, M. (2022). Predicting selfie-posting behavior through self-esteem, narcissism and exhibitionism among Indian Young Youth. Journal of Content Community and Communication, 15(8), 14-31. [CrossRef]

- Netrawati, N. (2022). The Appropriateness of Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Reduce Adolescent’s Social Media Addiction. Jurnal Neo Konseling, 4(3), 31-38. [CrossRef]

- Omori, K., & Allen, M. R. (2021). Narcissism as a predictor of number of selfies: A cross-cultural examination of Japanese and American postings. Communication Research Reports, 38(3), 186-194. [CrossRef]

- Oppong, D., Adjaottor, E. S., Addo, F.-M., Nyaledzigbor, W., Ofori-Amanfo, A. S., Chen, H.-P., & Ahorsu, D. K. (2022). The Mediating Role of Selfitis in the Associations between Self-Esteem, Problematic Social Media Use, Problematic Smartphone Use, Body-Self Appearance, and Psychological Distress among Young Ghanaian Adults. Healthcare, 10(12), 2500. [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, M., Rodríguez-Villalobos, J. M., Viciana, J., Guedea, J. C., Blanco, J. R., & Mayorga-Vega, D. (2021). Composition Factor Analysis and Factor Invariance of the Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PASTAS) in Sports and Non-Sports Practitioner Mexican Adolescents. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 20(3), 525-534. https://www.jssm.org/jssm-20-525.xml%3EFulltext .

- Oxford University. (2025). Selfie [Académica]. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/selfie?q=selfie.

- Petekkaya, E., Dokur, M., & Günay Budagova. (2021). The neurocognitive basis of selfie-related behaviors in adolescents. Kastamonu Medical Journal, 1(1), 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, K. M. D., Mahadewi, N. M. E., & Susianti, W. (2024). Push and pull factors of foreign tourists in choosing tirta empul spiritual tourism attraction, Gianyar Regency, Bali. Jurnal Kepariwisataan, 23(2), 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, C. P., & Sood, R. S. (2021). Selfie creating dual personalities: A study of selfie, narcissism and social media. Journal of Content, Community & Communication, 13(7), 360-371.

- Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890-902. [CrossRef]

- Richa, M., Nidhi, S., & Chhavi, T. (2021). Selfies, Individual Traits, and Gender: Decoding the Relationship. Trends in Psychology, 29(2), 261-282. [CrossRef]

- Ruvalcaba Arredondo, L., Ríos Rodríguez, L. del C., Carmona, E. A., & López González, A. J. (2023). Transversalidad, WhatsApp, smartphone y redes sociales en el trabajo, la socialización y la individualidad. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 14(1), 80-105. [CrossRef]

- S, S., & Mohanasundaram, T. (2024). Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Reporting Guidelines. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 24(7), 561-577. [CrossRef]

- Schettino, G., Fabbricatore, R., & Caso, D. (2023). “To be yourself or your selfies, that is the question”: The moderation role of gender, nationality, and privacy settings in the relationship between selfie-engagement and body shame. Psychology of Popular Media, 12(3), 268-278. [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Dark Triad of Personality and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Preliminary Study on the Mediating Role of Fear of Missing Out. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8463. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, H., Bush, K., Shvetz, C., Paquin, V., Morency, J., Hellemans, K. G., & Guimond, S. (2024). Longitudinal Problematic Social Media Use in Students and Its Association with Negative Mental Health Outcomes. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1551-1560. [CrossRef]

- Shi, D., DiStefano, C., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Lee, T. (2022). Evaluating SEM Model Fit with Small Degrees of Freedom. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 57(2-3), 179-207. [CrossRef]

- Tanzilli, A., Colli, A., Del Corno, F., & Lingiardi, V. (2016). Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Therapist Response Questionnaire. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(2), 147-158. [CrossRef]

- Tasgin, A., & Korucuk, M. (2018). Development of Foreign Language Lesson Satisfaction Scale (FLSS): Validity and Reliability Study. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 7(2), 66-77. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. G. (2020). Putting the “self” in selfies: How narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(1), 64-77. [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L. L. (1947). Multiple-factor analysis. Chicago: The University Chicago Press.

- Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij de Vaate, A. J. D. (Nadia), Keijer, M., & Konijn, E. A. (2020). Me, my selfie, and I: The relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D., Ghuhato, T., Rajkumar, E., George, A., John, R., & Abraham, J. (2024). Exploring the Reasons for Selfie-Taking and Selfie-Posting on Social Media with Its Effect on Psychological and Social Lives: A Study among Indian Youths. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(5), 389-398. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M. J., & Baker, S. A. (2017). The selfie and the transformation of the public–private distinction. Information, Communication & Society, 20(8), 1185-1203. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B., Campbell, W. K., Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2019). A Trifurcated Model of Narcissism: On the pivotal role of trait Antagonism. En J. D. Miller & D. R. Lynam (Eds.), The Handbook of Antagonism (pp. 221-235). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W., Luo, Y., & Chen, H. (2024). Does Thin-Ideal Internalization Increase Adolescent Girls’ Problematic Social Media Use? The Role of Selfie-Related Behaviors and Friendship Quality. Youth & Society, 56(3), 447-474. [CrossRef]

- Zurafa, Z., & Dewi, F. I. R. (2021). Social-Media Addiction Among Late Adolescents: Self-Esteem and Narcissism as Predictor. 1444-1449. [CrossRef]

| Factor 1 (Fc1) | Factor 2 (Fc2) | Factor 3 (Fc3) | Factor 4 (Fc4) | Uniqueness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSAS_4 | 0.828 | 0.345 | |||

| PSAS_3 | 0.802 | 0.354 | |||

| PSAS_5 | 0.734 | 0.47 | |||

| PSAS_9 | 0.714 | 0.496 | |||

| PSAS_2 | 0.668 | 0.508 | |||

| PSAS_6 | 0.665 | 0.491 | |||

| PSAS_8 | 0.651 | 0.603 | |||

| PSAS_7 | 0.631 | 0.594 | |||

| PSAS_1 | 0.552 | 0.578 | |||

| NPI_15 | 0.729 | 0.467 | |||

| NPI_14 | 0.723 | 0.498 | |||

| NPI_18 | 0.619 | 0.606 | |||

| NPI_3 | 0.54 | 0.678 | |||

| NPI_37 | 0.511 | 0.691 | |||

| NPI_38 | 0.5 | 0.592 | |||

| NPI_6 | 0.484 | 0.616 | |||

| NPI_1 | 0.431 | 0.688 | |||

| NPI_8 | 0.43 | 0.617 | |||

| NPI_16 | 0.412 | 0.636 | |||

| NPI_29 | 0.792 | 0.349 | |||

| NPI_28 | 0.761 | 0.339 | |||

| NPI_30 | 0.723 | 0.422 | |||

| NPI_23 | 0.983 | 0.038 | |||

| NPI_25 | 0.799 | 0.26 |

| Factor | Eigenvalues | Rotated solution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sums of squared loads | Proportion var. | Cumulative | ||

| Factor 1 | 5.755 | 4.493 | 0.187 | 0.187 |

| Factor 2 | 4.535 | 3.329 | 0.139 | 0.326 |

| Factor 3 | 2.275 | 2.48 | 0.103 | 0.429 |

| Factor 4 | 1.19 | 1.763 | 0.073 | 0.503 |

| Index | Valor |

|---|---|

| Comparative Adjustment Index (CFI) | 0.958 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.953 |

| Mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.07 |

| RMSEA 90 % IC lower limit | 0.063 |

| RMSEA 90 % IC upper limit | 0.077 |

| Root mean square error (SRMR) | 0.084 |

| Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) | 0.979 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).