1. Introduction

Rapid urban growth in developing countries has led to the proliferation of self-built structures, especially in peripheral areas where economic constraints and lack of access to professional technical assistance affect construction quality. In highly seismic contexts such as Peru, this situation takes on special relevance due to the interaction between empirical construction practices, non-standard materials, and the absence of earthquake-resistant design, factors that significantly increase the risk of recurrent seismic events associated with the Pacific Ring of Fire [

1]. This problem is shared by many Latin American countries, where self-construction is an urgent response to the need for housing, although with structural consequences that compromise the safety of the inhabitants.

Internationally, various studies have shown that non-engineered housing has critical deficiencies when subjected to seismic loads. In Mexico, González and Pérez demonstrated that the lack of geotechnical studies and ignorance of subsoil behavior generate severe structural problems, such as differential settlement and cracking in load-bearing walls [

2]. Similarly, Malavé and Pinoargote documented that the 2016 earthquake on the Ecuadorian coast revealed widespread failures in homes built without technical criteria, underscoring the need for structural analysis and adequate reinforcement in vulnerable areas [

3]. In Cuba, Aguilar identified that the presence of unstable soils and the absence of comprehensive assessment methodologies substantially increase the risk of failure in buildings constructed on karst terrain [

4].

In Asian regions with high seismicity, such as Sichuan (China), experimental studies conducted by Zhang, Guo, Liu, and He reveal that hybrid buildings with confined masonry elements and concrete porticos fail due to diagonal shear and weak floor mechanisms when there is an irregular distribution of walls and insufficient lateral stiffness [

5]. These findings coincide with the behavior documented in self-built Latin American homes, where deficiencies in confinement, irregular geometry, and lack of rigidity concentrate the risk of collapse.

In Peru, the problem has been widely documented. Arriola, in a study applied to self-built houses in Huaycán (Ate), determined that these are up to 45% more likely to fail structurally than buildings with technical supervision, due to poor compliance with Technical Standard E.030 and insufficient lateral stiffness in their structural configurations [

6]. Similarly, Acuña identified excessive distortions in the X-axis of a self-built home modeled with SAP2000, exceeding regulatory limits and evidencing failures associated with the absence of adequate structural design [

7]. In Moquegua, Flores found medium to high severity vulnerabilities in confined masonry houses built using empirical practices, while Ruiz reported that 77% of the buildings evaluated in Puyllucana (Cajamarca) have high seismic vulnerability due to the absence of professional supervision [

8,

9].

The city of Chimbote reflects these same conditions. In the Los Constructores settlement, many homes have been built without technical criteria, using inexpensive materials and without considering the requirements of the National Building Regulations. This situation increases exposure to seismic risk and highlights the need for studies that integrate structural analysis, soil characterization, and vulnerability assessment in self-built buildings.

Therefore, the main objective of this research is to analyze the incidence of structural vulnerability and seismic influence on the behavior of self-built buildings in the Los Constructores settlement, Nuevo Chimbote (2025). The study combines field inspections, geotechnical tests, and structural modeling using specialized software to identify the predominant failure mechanisms and propose reinforcement measures aimed at reducing seismic vulnerability. The results provide relevant technical evidence for strengthening structural safety and contribute to the guidelines of SDG 11, which aims to promote resilient and sustainable cities.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted using an applied approach aimed at understanding and reducing the structural vulnerability of self-built homes exposed to seismic hazards. A non-experimental, descriptive-comparative design was adopted, complemented by experimental procedures for soil analysis and structural performance verification. This approach made it possible to observe the actual conditions of the buildings without altering their characteristics, while incorporating instrumental techniques that strengthened the validity of the results [

1].

2.1. Study Area, Population, and Sample

The study was conducted in the Los Constructores settlement in Nuevo Chimbote, an area with a predominance of self-built homes and limited technical supervision. The population consisted of confined masonry buildings and porticos with more than two levels. The sample consisted of twenty dwellings selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria related to structural typology, age, and construction condition [

2].

2.2. Data Collection Techniques and Instruments

Structural characterization was carried out through direct observation, photographic recording, and architectural-structural surveying. A specially designed technical data sheet, based on the criteria of the National Building Regulations (E.060 and E.070), was used to document critical elements such as columns, load-bearing walls, reinforcements, stirrups, confinement, and visible pathological conditions. This data sheet made it possible to standardize the evaluation and build a comparative database.

2.3. Field and Laboratory Testing

In accordance with Peruvian Technical Standard E.050, test pits were excavated to extract representative samples of the terrain profile. Geotechnical tests included: particle size analysis according to ASTM D421, Atterberg limits according to ASTM D4318, natural moisture content according to ASTM D2216, in situ density, and penetration resistance to estimate the bearing capacity of the soil. The results allowed the soil to be classified and its stiffness, profile, and suitability for shallow foundations to be determined.

2.4. Structural Modeling and Seismic Analysis

A representative dwelling was selected from the sample and a three-dimensional model was created using specialized structural software (ETABS). Seismic loads were defined in accordance with Technical Standard E.030, taking into account local seismic zoning, the design spectrum, reduction factors, and relevant structural behavior parameters. The analysis yielded drifts, displacements, stresses, and predominant vibration modes, which were compared with regulatory limits.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

The data obtained in the field and laboratory were systematized using tables and figures, allowing structural vulnerability levels to be established and correlated with geometric, construction, and seismic variables. The modeling results were interpreted using comparative criteria, contrasting the behavior in each structural axis with the values permitted by the regulations.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study complied with the guidelines of the César Vallejo University Ethics Committee, ensuring confidentiality, accuracy in data collection, and exclusive use of technical information obtained in the field. Property owners were not identified, nor were the specific locations of the homes evaluated disclosed, thereby avoiding any compromise of participants’ privacy.

2.7. Use of Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence was used solely as a support tool to improve the clarity and consistency of the writing, without interfering in the generation, analysis, or interpretation of scientific data, or in the preparation of results or figures. All technical, methodological, and analytical content comes from the author’s fieldwork, testing, modeling, and professional judgment.

3. Results

3.1. On-Site Structural Vulnerability Assessment

The technical inspection carried out on the 20 selected homes made it possible to determine the level of structural vulnerability by applying the corresponding assessment form. The generalized results are presented in

Table 1, which shows an average vulnerability with a final weighted value of 2.1, mainly influenced by structural and geometric deficiencies.

Die Teilwerte wiesen auf drei kritische Komponenten hin:

Geometric aspects, where irregularities in the floor plan and insufficient load-bearing walls were given a weighting of 0.6;

Construction aspects, affected by deficiencies in mortar joints and the layout of masonry units (weighting 0.4);

Structural aspects, where problems in the details of columns, confinement beams, and mezzanines again achieved a weighting of 0.6.

These results made it possible to identify that the structural behavior of the evaluated dwellings depends significantly on the geometry and the confinement system, which are determining factors in self-built buildings.

3.2. Soil Testing: Physical and Mechanical Characteristics

Laboratory and field tests were conducted to determine the fundamental properties of the foundation soil. These included:

Modified Proctor test (maximum density and optimum moisture content);

Sieve analysis;

Atterberg limits test (liquid and plastic)

Light dynamic penetration test (DPL);

Determination of natural soil moisture content

3.2.1. Modified Proctor Test

The values obtained indicated a maximum dry density of 1,890 g/cm

3 on average for three samples collected, and an optimum moisture content of 8.8%, as shown in

Table 2.

These values are characteristic of dense and compact granular soils, which suggests good bearing capacity for foundations for common buildings.

3.2.2. Allowable Soil Capacity

The results obtained through correlations with the DPL values are consolidated in

Table 3, which shows allowable load capacities between 5.72 t/m

2 and 20.03 t/m

2 (equivalent to 0.57–2.00 kg/cm

2), within ranges typical of soils classified as Profile S2 (rigid soil).

These values confirmed that the terrain provides stable and safe conditions, ruling out the existence of geotechnical risks that could compromise the structural integrity of the buildings studied.

3.3. Structural Modeling and Seismic Behavior Verification

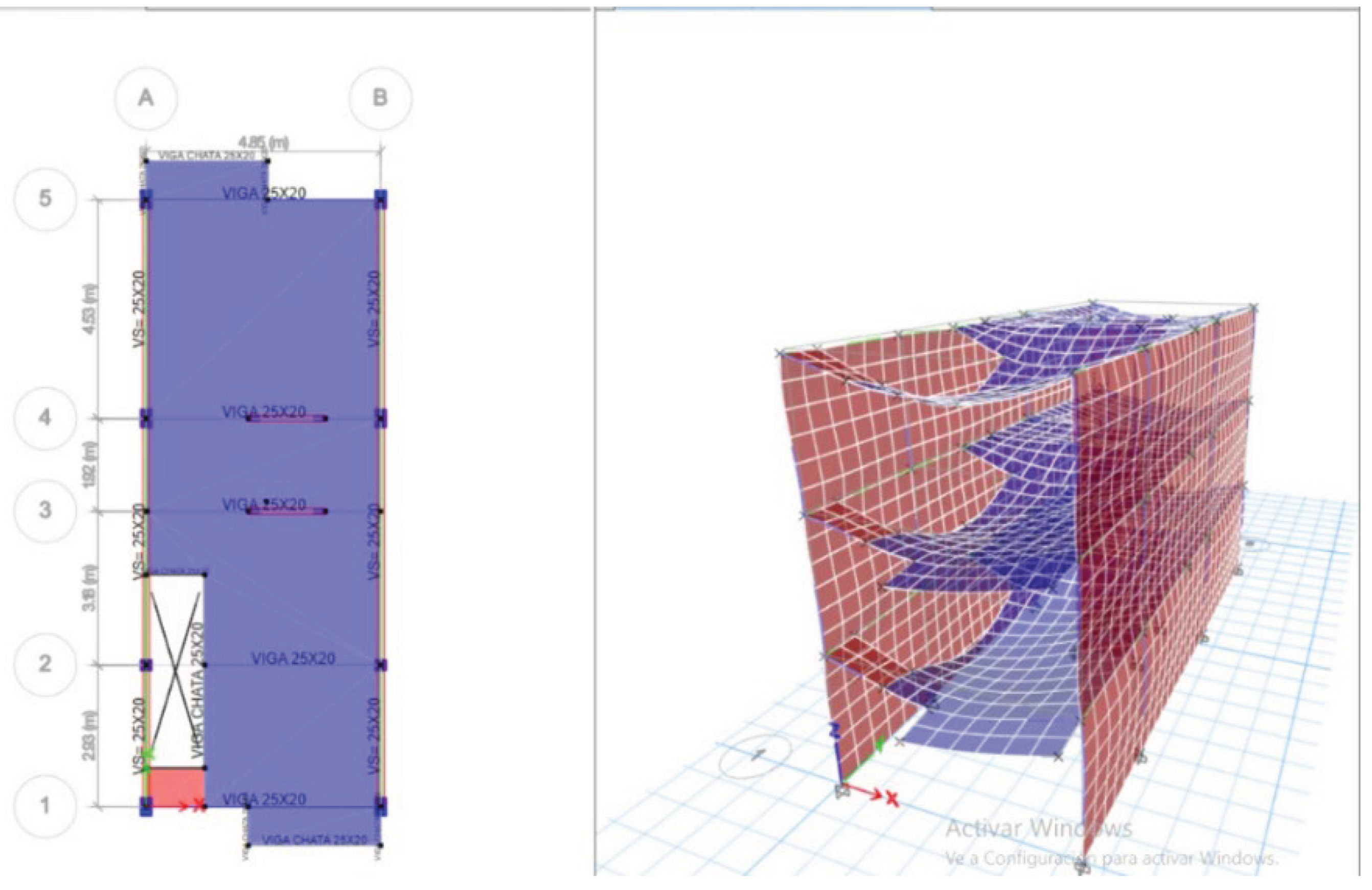

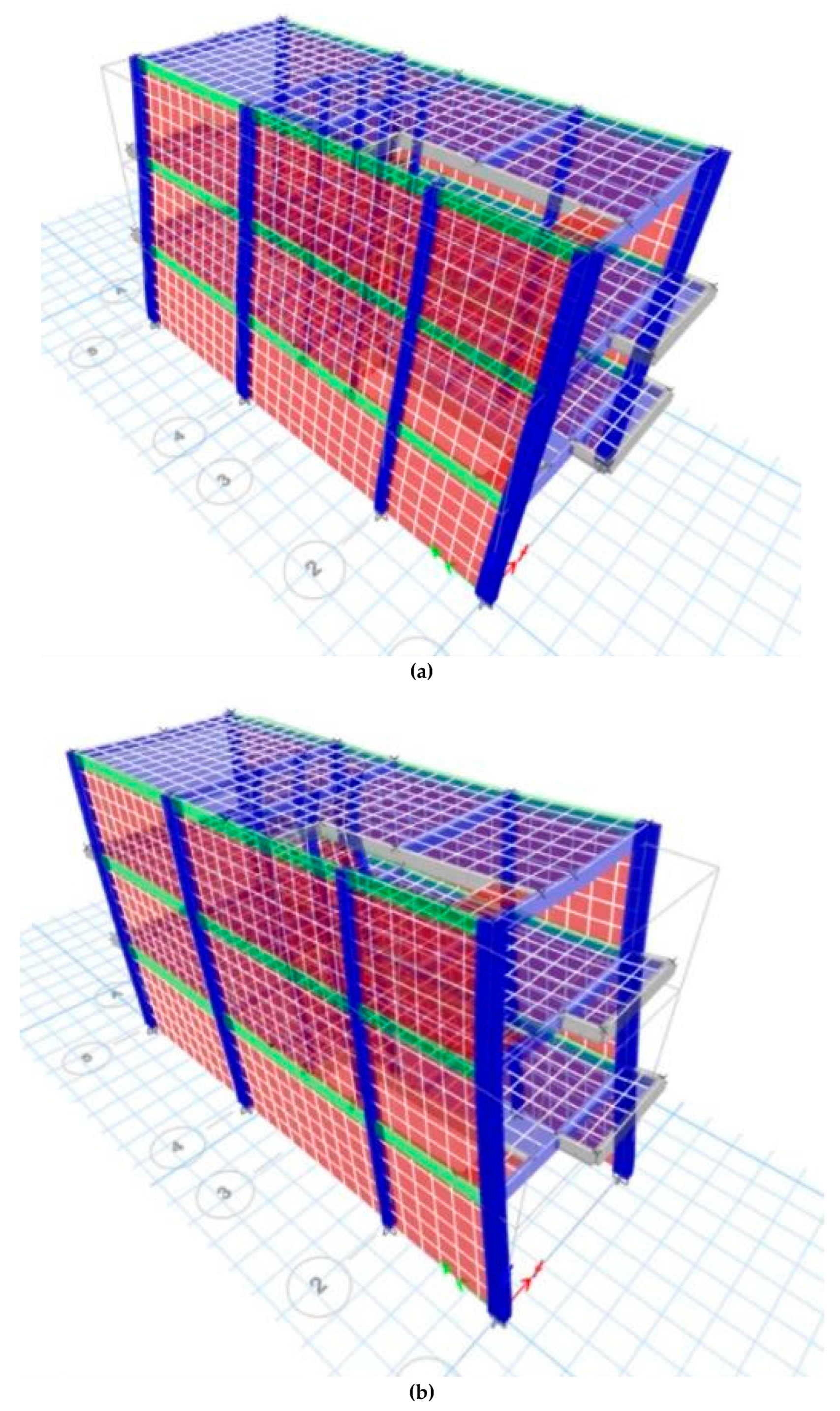

A representative dwelling was selected for modeling in ETABS, applying seismic loads in accordance with Technical Standard E.030. The analysis included verification of:

3.3.1. Wall Density and Lateral Stiffness

The analysis determined that the wall density on the X-axis had a value of 0.0064, which is below the regulatory minimum (0.0253). This insufficient lateral stiffness caused:

Greater displacement in the longitudinal direction;

Concentration of forces in first-level walls;

Unstable structural behavior in modal and dynamic analysis.

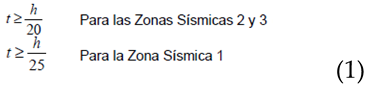

To determine the minimum wall density, the effective thickness of the element (brick) is taken into account in the first instance, as shown in the illustration in

Figure 1.

To verify the actual calculation, the cross-sectional area of the reinforced walls is taken into account, based on the typical floor area, as shown in equation 2. Performing this procedure yielded an unfavorable result in terms of wall consolidation compared to Peruvian Technical Standard E. 030.

3.4. Structural Damage Simulation

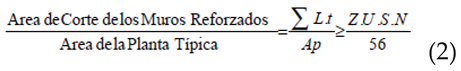

The final simulation of structural behavior allowed visualization of damage propagation during seismic action. The results are presented in

Figure 1, where considerable deformation in the longitudinal direction (X) and the onset of a brittle failure mechanism can be observed.

Figure 2.

Simulated structural damage.

Figure 2.

Simulated structural damage.

Formation of diagonal shear failures in masonry walls;

Accumulated lateral deformations;

Concentration of damage on the first level, characteristic of a weak floor.

This behavior confirms the results obtained in the vulnerability assessment and structural modeling verification.

3.5. Specific Conclusions from the Results

In summary, the results demonstrated that:

The evaluated dwellings have a medium vulnerability (2.1) associated mainly with geometric, construction, and structural deficiencies;

The foundation soil is rigid with high bearing capacity, ruling out the risk of geotechnical instability;

The representative dwelling showed a critical deficiency in rigidity on the X-axis, failing to meet minimum regulatory values;

Structural modeling revealed excessive drifts and the formation of weak floor mechanisms, a condition that could cause brittle failures or partial collapse in the event of a severe earthquake.

4. Discussion

The results of this study allow us to interpret the behavior of self-built buildings in the Los Constructores Human Settlement in response to seismic activity, in relation to the hypotheses proposed and the specialized literature. First, the hypothesis that structural vulnerability would be moderate due to construction and geometric deficiencies was confirmed. The field inspection recorded a value of 2.1, which coincides with previous research identifying recurring patterns of fragility in self-built homes, especially due to the absence of adequate confinement and the use of empirical construction criteria [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Similarly, soil characterization confirmed that bearing capacity is not the main vulnerability mechanism, given that the terrain corresponds to a rigid S2 profile. This finding allowed us to rule out the alternative hypothesis that associated the risk with geotechnical deficiencies, in accordance with studies conducted in urban areas of the Peruvian coast where the soils are sufficiently rigid for one- to three-story buildings [

5,

6]. Thus, the problem lies in the construction and not in the ground support.

Structural modeling verified the second hypothesis, which suggested that structural failures were directly related to low lateral stiffness. The wall density on the X-axis (0.0064), well below the regulatory minimum (0.0253), produced a lateral drift ten times greater than on the Y-axis. This asymmetrical behavior coincides with studies describing failure mechanisms due to torsion and excessive displacement in confined masonry houses with irregular wall distribution [

7,

8,

9]. The evidence confirms that the lack of confinement elements, inadequate stirrup spacing, and architectural irregularities significantly increase the fragility of the system, reinforcing the findings of Arriola Prieto [

1] and post-earthquake assessments carried out in self-build contexts.

Likewise, comparison with international studies on informal housing in Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador shows similarities in the identification of failures dominated by diagonal shear and low ductility due to the absence of technical criteria in structural execution [

10,

11,12]. These parallels support the third hypothesis, which stated that structural modeling would reveal unfavorable seismic behavior resulting from construction errors typical of self-construction.

The discussion of the results also allows for an analysis of the practical implications of the reinforcement proposal. Increasing wall density, correcting confinement, and improving structural continuity are in line with recommendations issued by specialized institutions such as PUCP and CISMID [

3,

7,

8]. These measures are technically feasible, low-cost, and implementable in marginal urban contexts, which strengthens the fourth hypothesis, aimed at demonstrating that seismic performance can be improved through simple, normatively supported interventions.

Broadly speaking, the results show that structural vulnerability in human settlements such as Los Constructores is a multi-causal phenomenon, associated with both informal construction and the absence of technical guidance and the reproduction of empirical building models. The research provides a replicable methodological framework based on direct inspection, basic soil testing, and structural modeling, which can be used in future research aimed at assessing seismic risk in marginal urban areas.

Overall, the findings confirm the validity of the hypotheses proposed and show that the main mechanism of vulnerability is insufficient lateral stiffness resulting from poor structural configurations, rather than soil conditions. This result underscores the need to promote accessible intervention strategies, technical training programs, and ongoing studies to reduce seismic risk in vulnerable communities.

5. Conclusions

El análisis de las edificaciones autoconstruidas del Asentamiento Humano Los Constructores permitió identificar que la vulnerabilidad estructural observada responde principalmente a deficiencias en la configuración y en la continuidad de los elementos resistentes, antes que a limitaciones del suelo de cimentación. La inspección técnica demostró que las viviendas presentan un nivel de vulnerabilidad medio, determinado por errores recurrentes en el confinamiento, la distribución irregular de muros y la ausencia de criterios técnicos en el proceso constructivo. La caracterización del terreno confirmó que se trata de un suelo rígido tipo S2 con adecuada capacidad admisible, descartando que la falla potencial esté asociada a problemas geotécnicos. El modelado estructural verificó que la baja densidad de muros en el eje X constituye el mecanismo crítico de falla, generando derivas laterales excesivas y un comportamiento frágil ante cargas sísmicas. Esta condición fue determinante para la simulación de colapso anticipado bajo el espectro de diseño. Finalmente, los resultados demostraron que la incorporación de muros de corte, la corrección del confinamiento y la mejora de la continuidad estructural representan alternativas viables y eficaces para mitigar el riesgo sísmico. En síntesis, la investigación confirma que el reforzamiento focalizado, basado en criterios normativos y adaptado al contexto urbano marginal, puede mejorar significativamente la resiliencia de las viviendas autoconstruidas frente a futuros eventos sísmicos.

6. Patents

No patents were generated from this research.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization, Franklin Pérez and Kevin Méndez; methodology, Franklin Pérez and Kevin Méndez; software, Franklin Pérez; validation, Franklin Pérez, Kevin Méndez and José Pepe Muñoz Arana; formal analysis, Franklin Pérez; investigation, Franklin Pérez and Kevin Méndez; resources, Franklin Pérez; data curation, Franklin Pérez; writing—original draft preparation, Franklin Pérez; writing—review and editing, Kevin Méndez; visualization, Kevin Méndez; supervision, José Pepe Muñoz Arana; project administration, Franklin Pérez. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to their academic advisor, Mgtr. José Pepe Muñoz Arana, as well as to their families and the Universidad César Vallejo for their continuous support throughout the development of this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025) to assist with academic editing and refinement. The authors reviewed and validated all generated content and assume full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA.HH. |

Asentamiento humano |

| ACI |

American Concrete Institute |

| AST |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ETABS |

Extended Three-Dimensional Analysis of Building Systems |

| NTP |

Norma Tecnica Peruana |

| PUCP |

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú |

| RNE |

Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

References

- Arriola Prieto, C. Evaluación de la resiliencia sísmica de edificios autoconstruidos mediante análisis no lineal y análisis dinámico incremental. Llamkasun 2024, 5(2), 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Acuña García, R.S. Evaluación de la vulnerabilidad sísmica de viviendas autoconstruidas de una provincia peruana con riesgo sísmico. High Tech Engineering Journal 2023, 3(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Castro Rojas, B.P.; Perdomo, B. La autoconstrucción en la ciudad de Lima: hábito poblacional que configura el entorno urbano. Contexto 2023, 18(27), 15. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Gao, X.; Han, W.; Wang, J. Renewal Framework for Self-Built Houses in “Village-to-Community” Areas with a Focus on Safety and Resilience. Buildings 2023, 13(12), 3003. [CrossRef]

- Escobar González, I.; González de la Rocha, M. Pobreza y vivienda en Guadalajara, México, de 1980 a 2020. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 2024, 86(4). [CrossRef]

- Laurente Lliuyacc, A.; Ramos Salazar, J.P. Vulnerabilidad estructural aplicando el método italiano para estimar la seguridad sísmica en instituciones educativas en La Molina. Tesis Profesional, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima, Perú, 2020.

- Leyva Chang, K.M.; Diez Zaldívar, E.R.; Villalón Semanat, M. Evaluación de la vulnerabilidad sísmica estructural y estimación de daños en edificaciones religiosas patrimoniales en Santiago de Cuba. REDER 2025, 9(1), 232–242.

- Li, S.-Q.; Zhang, C.; Qin, P.-F. Seismic vulnerability analysis of adobe structures considering historical Chinese seismic intensity standards. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2025, 197, 109543. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.M.J.; Cerna Vásquez, M.A.; Soto, S.E. Seismic vulnerability and structural reinforcement of public educational institutions in a Peruvian province with seismic risk. LACCEI 2022, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zobin, V.M.; Plascencia, I. Seismic risk in the State of Colima, Mexico: Application of a Simplified Methodology of Seismic Risk Evaluation for Localities with Low-Rise, Non-Engineered Housing. Geofísica Internacional 2022, 61(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, X.; He, F. Seismic performance of hybrid RC frame–masonry structures based on shaking table testing. Engineering Structures 2025, 333, 120174. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).