1. Introduction

Topical formulations (for skincare) are increasingly recognised for their potential to induce

systemic effects on metabolism and oxidative balance due to percutaneous absorption of various chemical ingredients. Public health concerns surrounding unregulated products stem from research linking certain compounds to metabolic disruption, oxidative stress, and chronic health issues [

1,

2]. The inclusion of calcium hypochlorite amongst other chemicals into organic creams is becoming of public health concern [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Reports indicate that these formulations are increasingly incorporated (often inappropriately) into some artisanal and commercial skin-lightening products. Although valued for its o rapid depigmenting effects, the inclusion of calcium hypochlorite in topical cosmetics occurs largely without regulatory control, raising questions about their safety and systemic impact [

5,

6].

Calcium hypochlorite is a potent oxidizing and disinfectant agent commonly used in sanitation, water treatment, and household hygiene products [

3,

4]. When applied to the skin, it can disrupt the integrity of the epidermal barrier and react with moisture or organic material to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hypochlorous acid [

3,

4]. Excessive ROS production can overwhelm endogenous antioxidant systems, resulting in oxidative stress that promotes lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, DNA damage, and broader metabolic disturbances [

7,

8]. Such oxidative insults can modify systemic lipid regulation, potentially contributing to dyslipidaemia and increasing long-term cardiometabolic risk [

9,

10].

Despite extensive documentation of the irritant and corrosive effects of hypochlorite on epithelial surfaces, its systemic biochemical effects following chronic dermal exposure remain poorly explored [

11]. This gap in knowledge is of particular concern in regions where organic or homemade skin-lightening creams are widely available and often used without adequate quality control. Consequently, calcium hypochlorite–containing products may pose significant but under-recognised health risks beyond their intended cosmetic effects. In trying to understand this area of research, rabbits provide a suitable model for dermal toxicology studies due to their permeable skin and sensitivity to oxidative/metabolic perturbations [

12].

Investigating the biochemical consequences of repeated topical application of hypochlorite-containing creams is therefore essential for understanding the broader health implications of these increasingly popular formulations. This study examines the effects of a calcium hypochlorite-based organic cream on glucose levels, lipid profile indices and oxidative stress markers in rabbits. By evaluating serum lipid parameters, antioxidant enzyme activities, and indicators of oxidative damage, the study offers important insights into the metabolic and oxidative consequences of dermal exposure to hypochlorite-containing skin-lightening products. The findings would possibly underscore the potential systemic risks associated with unregulated cosmetic formulations and highlight the need for stronger safety oversight within the skincare industry.

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.3. Chemicals and Drugs

Calcium hypochlorite solution, Coconut Oil

2.3. Location of Study

The study was carried out in the Lagos State University College of Medicine (LASUCOM) Pharmacology Laboratory. The study complied with Lagos State University guidelines for animal care and welfare. The LASUCOM Animal Ethics Committee approved the study.

2.4. Animals

Twenty male New Zealand white rabbits obtained from the animal house were used. The rabbits were kept in cages in the LASUCOM Animal House and maintained at room temperature with approximately 12 hours dark and 12 hours light cycle. The rabbits were housed in a controlled environment and monitored daily for signs of health and well-being for one week prior to commencement of study. This observation period allowed for acclimatisation to the laboratory conditions. The animals were fed laboratory chow and water ad libitum.

2.5. Ethical Approval and General Considerations

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the approved protocols of the Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, Lagos State University, College of Medicine, abiding by the regulations for animal care and use outlined in European Council Directive (EU2010/63) on scientific procedures involving living animals. The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal experiments were followed judiciously

2.6. Preparation of Calcium-Hypochlorite Cream

The calcium hypochlorite topical formulations were prepared following standard cream preparation protocols under quality-controlled conditions. A standard oil-in-water emulsion cream was produced with a target batch size of 100 g and an active concentration of approximately 1% w/w calcium hypochlorite. This concentration was selected to reflect levels commonly reported in certain artisanal skin-lightening creams while remaining manageable for controlled dermal exposure studies. The base formulation consisted of an oil phase and an aqueous phase. The oil phase was composed of petroleum jelly and coconut oil, each contributing 10 g to the mixture, along with 8 g of emulsifying wax (cetostearyl alcohol), which served as the primary emulsifying agent [

13]. The aqueous phase contained 65 g of distilled water and 3 g of glycerin as a humectant.

Calcium hypochlorite powder (1.5 g) served as the active ingredient and was added in an amount sufficient to yield approximately 1% available chlorine in the final formulation, after accounting for expected degradation losses. The preparation followed a standard emulsion-forming process. First, the oil-phase components: petroleum jelly, coconut oil, and emulsifying wax were combined and heated in a water bath to 70–75 °C until fully melted. In a separate beaker, the aqueous-phase ingredients: distilled water and glycerin, were warmed to approximately the same temperature. Once both phases reached uniform temperature, the heated aqueous phase was slowly-introduced into the oil phase with continuous stirring using a magnetic stirrer or handheld homogeniser. This process was continued until a consistent and homogeneous cream base was formed. Calcium hypochlorite was added only after the cream base had cooled to below 40 °C to minimise thermal decomposition. The appropriate quantities of calcium hypochlorite powder were weighed separately for each concentration: 0.1 g for the 0.1% formulation, 0.3 g for the 0.3% formulation, and 1.0 g for the 1.0% formulation, each corresponding to the total 100 g batch weight. The powder was gently folded into the cooled emulsion with minimal aeration. The prepared cream was then transferred into airtight, opaque containers to reduce light exposure, and stored at room temperature until use.

2.7. Daily Application Method

Before treatment, a 4 × 6 cm area of dorsal skin was carefully shaved for each rabbit to ensure consistent dermal exposure. The assigned dose of cream was measured accurately using a micropipette, syringe, or calibrated spatula, depending on the viscosity of the formulation. The cream was then applied gently to the shaved area and spread evenly across the surface without applying pressure that could irritate the skin or enhance absorption artificially. Following application, the animals were kept under non-occluded conditions to allow natural absorption of the formulation without any covering that might alter permeability or trap moisture [

14].

2.8. Experimental Methodology

Twenty (20) healthy adult male rabbits weighing between 2.0–2.5 kg each was randomly-assigned to four groups (n = 5 per group): Group I: Control (coconut oil vehicle only), Group II: ‘Low dose’ cream (0.1 mL/application), Group III: ‘Mid-dose’ cream (0.3 mL/application), Group IV: ‘High dose’ cream (1.0 mL/application).

Erythema in rabbits refers to redness or inflammation of the skin, often indicative of irritation, infection, or disease. To check for erythema in rabbits: Animals were observed daily for any changes in skin colour, texture, or overall appearance. Redness, swelling, or inflammation were specifically looked for on the ears, face, legs, and body. Additionally, any lesions, crusts, or scabs were checked to assess skin health. The Draize scale was used to grade erythema with no erythema being graded as O, very slight erythema (barely perceptible) was graded as I, slight erythema (pale pink) was graded as 2, Moderate erythema (pink) was graded as 3, Severe erythema (bright red) was graded as 4 [

15]. The hair from a 4 -6cm area on the dorsal region of each rabbit was shaved to allow direct skin exposure. The cream was applied daily to the shaved area of the flank for 28 days.

2.9. Euthanasia of Animals

Rabbits from all groups were euthanised after twenty-eight days exposure to calcium hypochlorite-containing organic cream. The rabbits were gently introduced into a container with chloroform, which is promptly sealed to contain the chloroform vapours. As the rabbit inhales the chloroform fumes, it loses consciousness within a few minutes, entering a state of deep anaesthesia. The rabbits were observed for signs of anaesthesia like drowsiness and loss of consciousness and the rabbits were euthanised after loss of reflexes.

2.10. Blood Sample Collection

Blood samples were collected through the marginal ear vein, using a sterile syringe and needle to ensure aseptic technique. The collected samples were then transferred into universal tubes after which it was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 20 minutes using a desktop centrifuge (Surgifriend centrifuge, Model SMBO-2, England). This process separates the sera and plasma from the blood cells. The sera were aliquoted into Eppendorf tubes and stored at -20°c until used.

2.11. Glucose Assay

The glucose levels were assessed in all sera from all groups using the glucose oxidase method as previously described [

16].

2.12. Assessment of Liver Function Tests

Alanine Transaminase, aspartate transaminase, alkaline phosphatase and albumin levels were assayed using commercially-available kits following the instructions of the manufacturer.

2.13. Assessment of Malondialdehyde Concentration

Malondialdehyde concentration in serum was determined using Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay as previously described [

17].

2.14. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Assay

The assay for SOD is based on the antioxidation of pyrogallol in a basic medium. Briefly, a buffer solution, specifically a 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.8, was prepared. The blood sample was then diluted appropriately in this buffer. Next, a reaction mixture was prepared, which included the buffer, the substrate (such as pyrogallol or NBT), and the diluted sample. The mixture was incubated at 25°C for a specific period, typically between 10 and 30 minutes, to allow the reaction to proceed. Finally, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at specific wavelength of 420nm using a spectrophotometer. Superoxide dismutase activity was calculated as percentage inhibition of pyrogallol autoxidation by the blood sample as previously described [

18].

2.14. Catalase and Reduced Glutathione Assay

Catalase activity in the blood was assayed as previously described [

19] 100 ul of blood sample was added to 1.9 ml of phosphate buffer (PH 74). The decrease in extinction was measured at 240nm, I min interval for 3 mins immediately after adding 1ml of 11mM hydrogen peroxide in buffer. A sample control was placed in a reference cuvette and the blood sample was replaced with 100ul of distilled water. Activity of Catalase was calculated using the moles extinction coefficient 40cm.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, were assayed using UV/visible spectrophotometric method. A buffer solution, specifically a 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, was prepared. The blood sample was then diluted appropriately in this buffer. A reaction mixture was prepared, which included the buffer, the reagent DTNB, and the diluted sample. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for a specific period, typically between 10 and 15 minutes, to allow the reaction to proceed. Finally, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at a wavelength of 412 nm using a spectrophotometer, as the formation of the coloured product indicates the concentration of GSH in the sample [

19].

2.15. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were analysed using students t-test, and p-value ≥ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Calcium Hypochlorite on Erythema Response

The erythema responses (

Table 1) among different groups of rabbits were evaluated following the application of calcium hypochlorite incorporated cream over the exposure period. Rabbits in group 1 (vehicle control) and Group 2(Calcium hypochlorite at 0.1 ml) showed no redness of any area of their skin. Rabbits in group 3 initially experienced slight redness, which worsened by the 3rd week but was completely resolved by the 4th week, suggesting a temporary skin reaction to the cream. However, those in group 4 showed a similar trend of erythema which did not resolve suggesting a longer-lasting irritant effect.

3.2. Effect of Calcium Hypochlorite on Liver Function Parameters

Topical exposure to the calcium hypochlorite-containing cream produced dose-dependent alterations in liver function biomarkers (

Table 2), reflecting varying degrees of hepatic stress or metabolic response. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) showed a notable increase in the two lower-dose groups compared with the vehicle-treated animals. AST rose from 6.00 ± 0.55 IU/mL in the control group to 14.00 ± 0.88 IU/mL in the 0.1 mL group and further to 16.00 ± 0.25 IU/mL in the 0.3 mL group. These elevations suggest that lower concentrations of calcium hypochlorite were associated with hepatocellular stress or increased leakage of intracellular enzymes into the circulation. Interestingly, AST levels reduced at the highest dose (8.00 ± 0.37 IU/mL), approaching control values, possibly indicating reduced systemic absorption at higher cream volumes or an adaptive physiological response. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels increased from 12.00 ± 0.24 IU/mL in the vehicle group to 19.00 ± 0.71 IU/mL in the 0.1 mL group and peaked at 26.00 ± 0.06 IU/mL in the 0.3 mL group. These elevations in ALT, an enzyme more specific to hepatocyte injury further support the likelihood of mild hepatocellular toxicity or inflammatory response due to dermal exposure. At 1.0 mL, ALT decreased to 18.00 ± 0.93 IU/mL, again suggesting a possible attenuation of toxicity at higher doses.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels increased slightly from 68.00 ± 0.23 IU/mL in controls to 72.00 ± 0.89 IU/mL at 0.1 mL, followed by a substantial rise to 101.00 ± 0.43 IU/mL at 0.3 mL. This large increase may indicate cholestatic stress, disruption of membrane transport mechanisms, or enhanced metabolic demand on hepatobiliary pathways. At the 1.0 mL dose, ALP decreased to 70.00 ± 0.61 IU/mL, returning close to baseline levels. The marked peak at the intermediate dose again suggests non-linear kinetics characteristic of dose-dependent oxidative stress or differential dermal absorption. Albumin (ALB) levels decreased slightly from 35.50 ± 0.07 IU/mL in the vehicle group to 33.80 ± 0.02 IU/mL at the 0.1 mL dose, suggesting a minor suppression of hepatic synthetic function. However, albumin increased above control values at the higher doses, 41.20 ± 0.99 IU/mL at 0.3 mL and 44.80 ± 0.12 IU/mL at 1.0 mL. This increase may reflect compensatory upregulation of protein synthesis, dehydration-induced concentration effects, or altered hepatic metabolism in response to oxidative or chemical stress. Overall, the enzyme profile suggests that dermal exposure to calcium hypochlorite cream may induce mild to moderate hepatocellular and hepatobiliary disturbances, particularly at lower and intermediate doses. The non-linear response pattern across doses suggests complex interactions between dermal absorption, systemic exposure, and hepatic adaptation. The reduction in enzyme levels at the highest dose may indicate reduced permeability, enzyme saturation, or adaptive detoxification mechanisms

3.3. Effect of Calcium Hypochlorite Cream on Oxidative Stress Markers

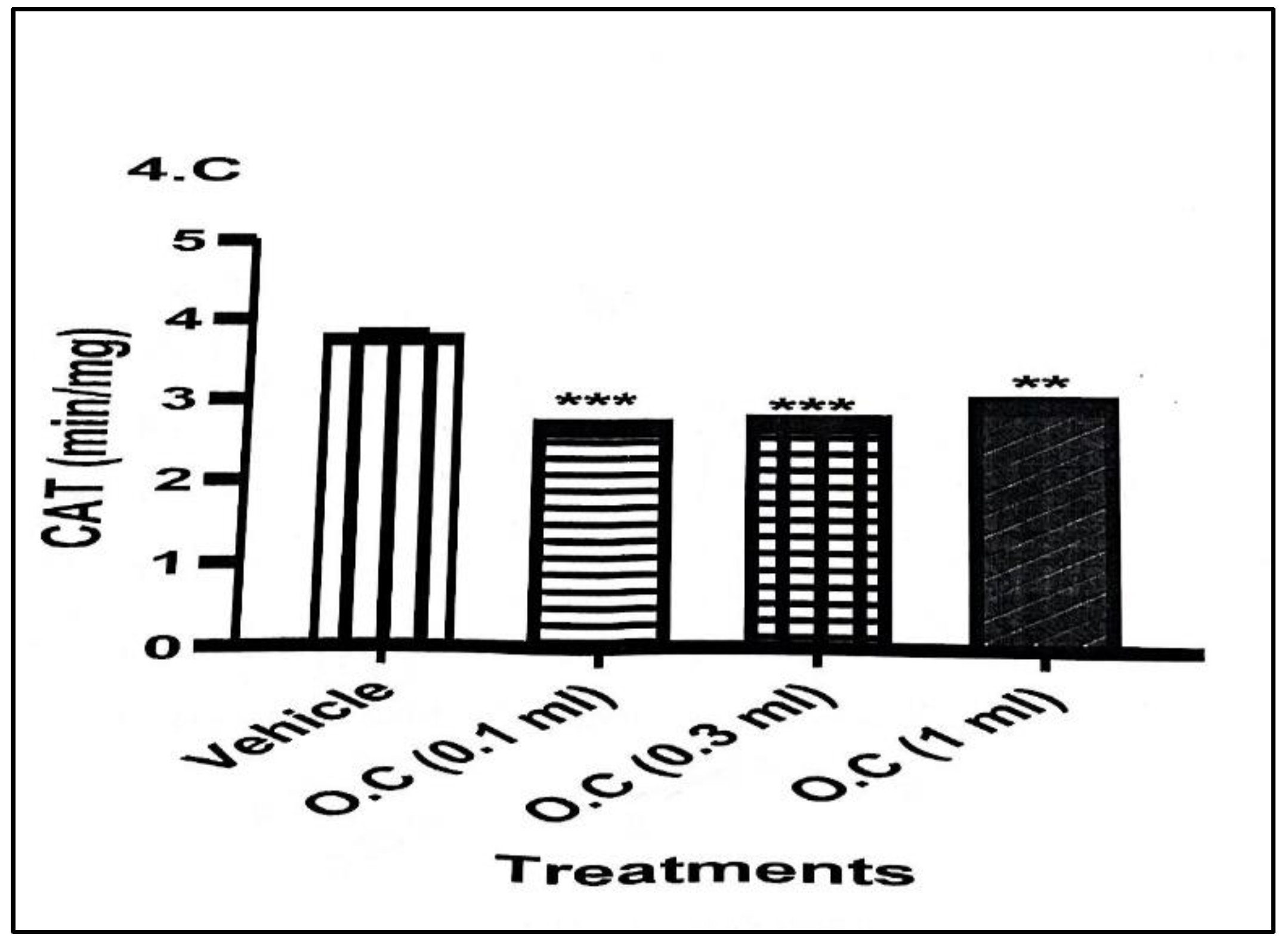

Topical exposure to the calcium hypochlorite–containing organic cream produced no significant alterations in oxidative stress markers compared with rabbits in the vehicle-treated group. Catalase (CAT) activity (

Figure 1) showed a marked reduction across all treatment doses. The decline was most pronounced in the 0.1 mL group, where CAT activity decreased from 3.77 ± 0.08 min/mg protein in the vehicle group to 2.68 ± 0.04 min/mg protein, representing a highly significant reduction. Similar but slightly less pronounced decreases were observed in the 0.3 mL and 1.0 mL groups, indicating a consistent suppression of CAT activity following cream application.

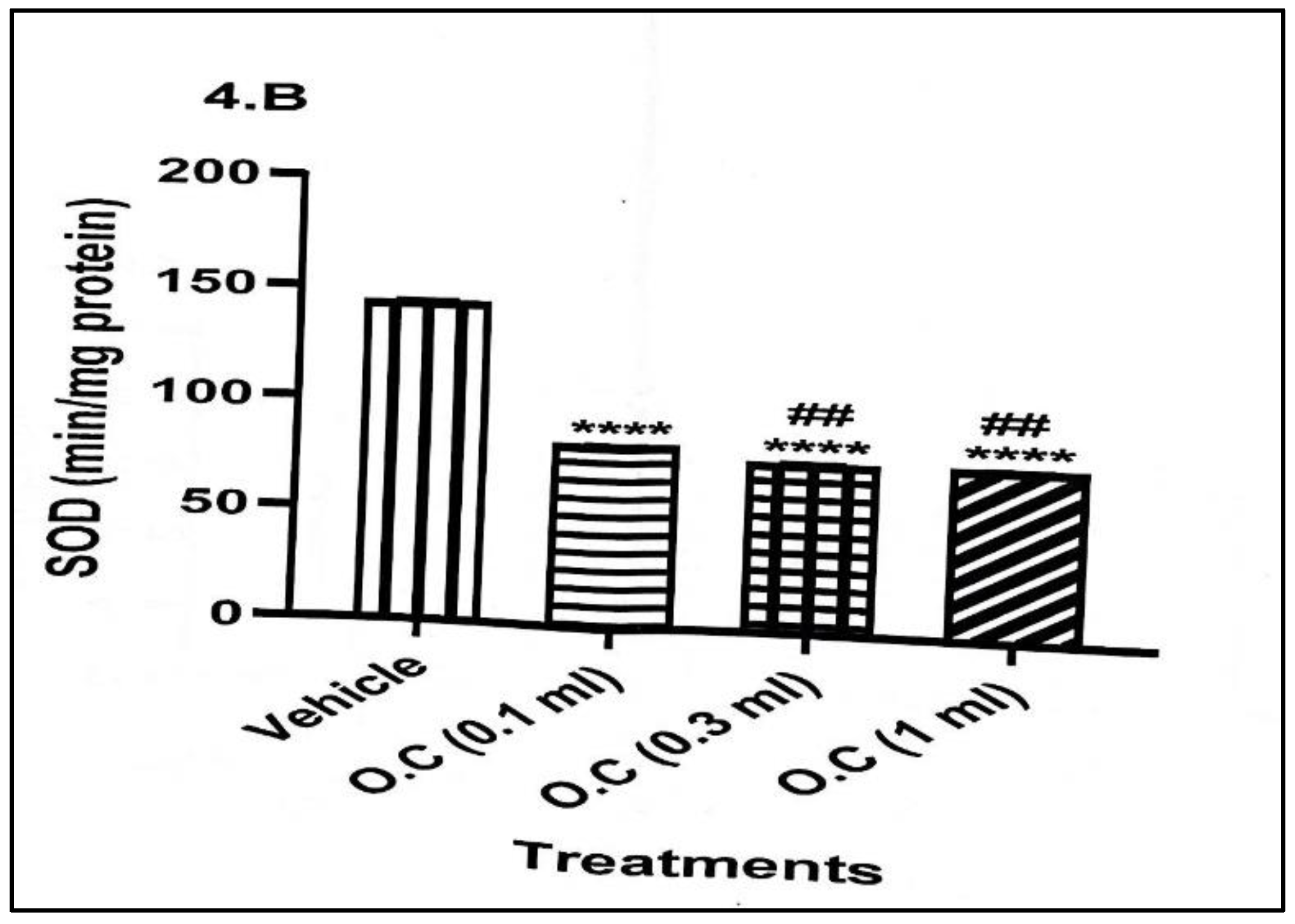

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (

Figure 2) was also significantly reduced in all treated groups relative to the vehicle. Activity of SOD dropped significantly from 143.60 ± 0.81 min/mg protein in the control animals to 81.03 ± 0.55 min/mg protein in the 0.1 mL group and further to approximately 75 min/mg protein in both the 0.3- and 1.0-mL groups. This suggests a strong and dose-independent inhibition of SOD, indicating compromised frontline antioxidant defence.

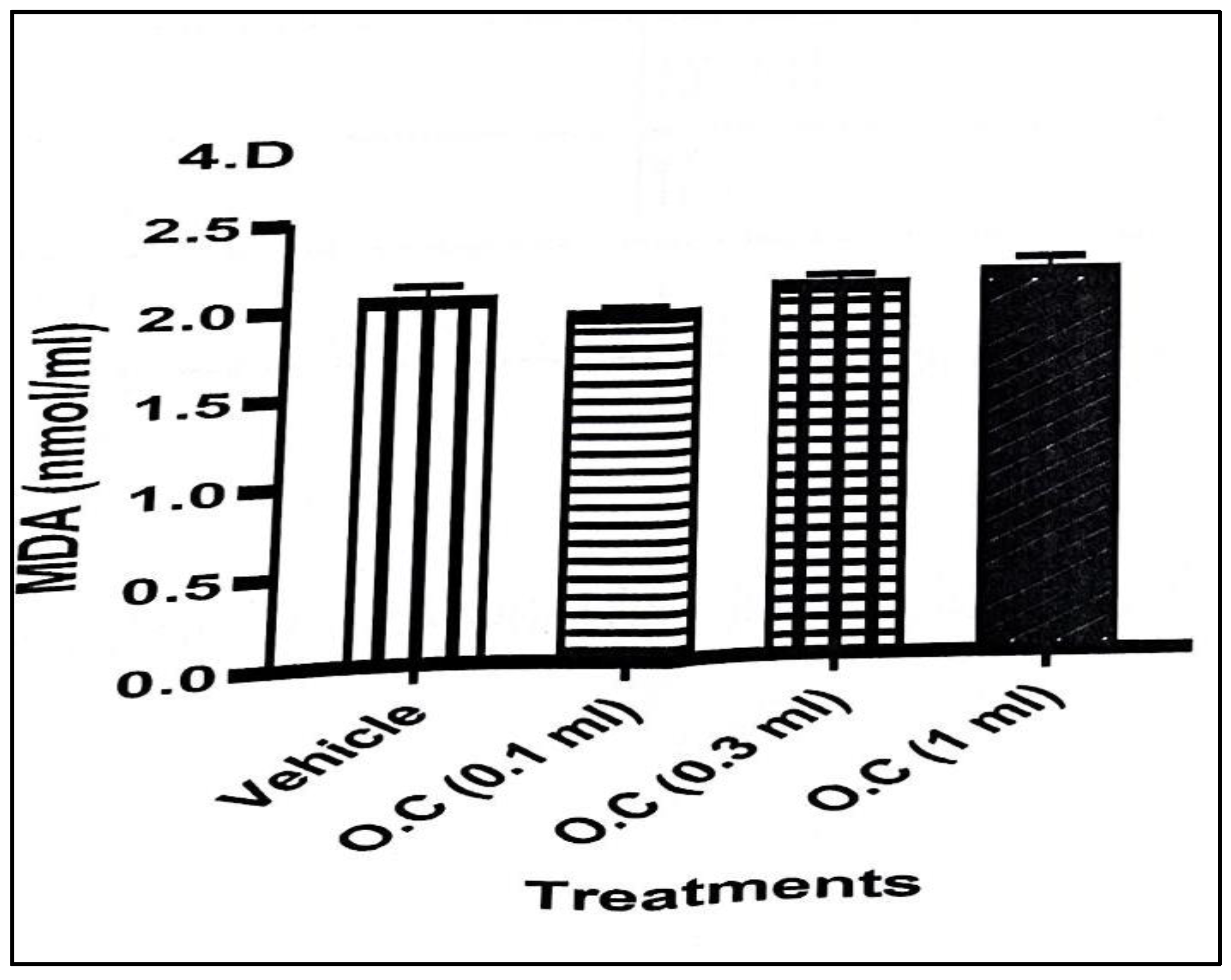

Malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation (

Figure 3), showed a mild but non-significant increase across treatment groups. While MDA values rose slightly from 2.06 ± 0.08 nmol/mL in the vehicle to values ranging between 1.96 and 2.16 nmol/mL in treated animals, these changes did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that the oxidative damage to lipids was modest or still in an early phase.

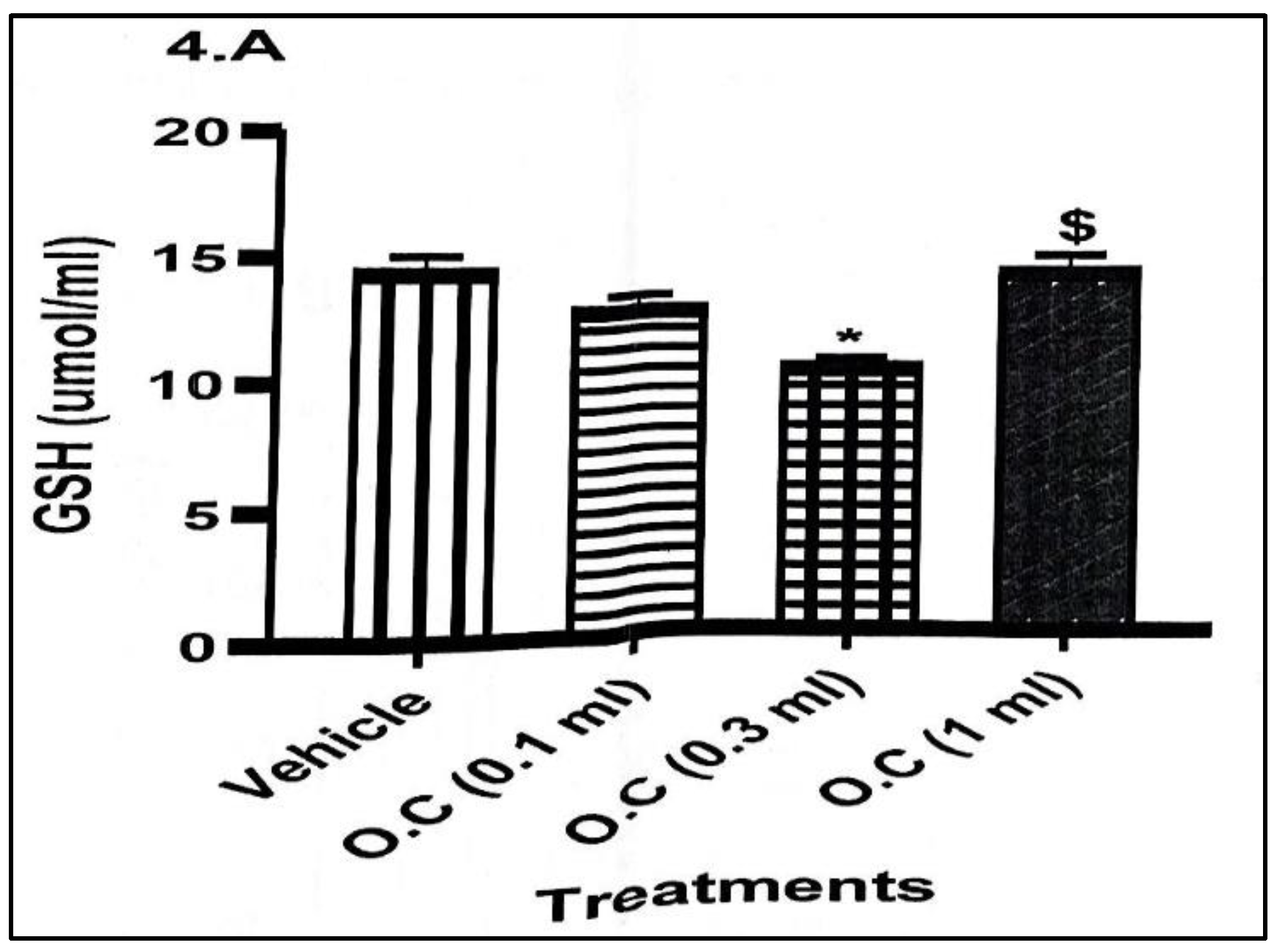

Reduced glutathione (GSH) concentrations (

Figure 4) showed a downward trend, indicating depletion of endogenous antioxidant reserves. Levels of GSH decreased from 14.34 ± 0.69 μmol/mL in the vehicle group to 12.81 ± 0.57 μmol/mL in the 0.1 mL group and reached the lowest level (10.49 ± 0.33 μmol/mL) in the 0.3 mL group, where the reduction was statistically significant. The 1.0 mL group showed partial recovery (12.57 ± 0.10 μmol/mL), though levels remained below the control.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that topical application of calcium hypochlorite cream consistently suppressed key antioxidant enzymes (CAT and SOD) and reduced GSH levels, indicating impaired oxidative defence. Although MDA levels did not rise significantly, the combined decline in enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants suggests an increased vulnerability to oxidative stress with dermal exposure to the cream.

3.4. Effect of Calcium Hypochlorite Cream on Serum Glucose Levels

Glucose levels (

Table 3) in the vehicle-treated rabbits averaged 10.13 ± 0.54 mmol/L, representing normal baseline glycaemic status for the animals. Topical exposure to the calcium hypochlorite–containing cream produced varying effects on glycaemic regulation across doses. In the 0.1 mL treatment group, the recorded glucose value (22.0 ± 0.14 mmol/L) was elevated relative to the control. Indicating significant hyperglycaemia following dermal exposure. This suggests that even minimal absorption of calcium hypochlorite may interfere with glucose regulation, possibly through oxidative impairment of insulin signaling or stress-related metabolic shifts. In the 0.3 mL group, blood glucose remained markedly elevated at 19.61 ± 0.27 mmol/L, though slightly lower than in the 0.1 mL group. The persistent hyperglycaemia at this intermediate dose indicates that calcium hypochlorite continues to exert a strong metabolic effect across increasing concentrations. At the highest exposure level (1.0 mL), glucose concentrations were still elevated (14.66 ± 0.71 mmol/L) but showed a relative decline compared with the lower doses.

This attenuation may reflect decreased percutaneous absorption at higher cream volumes, dose-dependent enzyme saturation, or partial metabolic compensation by the animals. Overall, the results demonstrate that topical application of calcium hypochlorite cream disrupts normal glucose homeostasis, leading to significant hyperglycaemia across all treated groups. The non-linear response pattern suggests complex interactions between dose, absorption dynamics, and metabolic adaptation.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the dermatological, oxidative, and metabolic effects of topical exposure to an organic cream containing calcium hypochlorite in rabbits. The findings provide important insights into the potential systemic toxicity of hypochlorite-contaminated cosmetic formulations, particularly those used for skin lightening. Overall, the results demonstrated that repeated dermal application of calcium hypochlorite cream induces cutaneous irritation, suppresses major antioxidant defenses, and alters glucose homeostasis.

The erythema patterns observed in this study indicate that calcium hypochlorite possesses irritant properties when incorporated into topical formulations. While the lowest dose (0.1 mL) produced no visible redness and resembled the vehicle group, moderate (0.3 mL) and high (1.0 mL) doses triggered varying degrees of skin irritation. Erythema in the 0.3 mL group was transient and resolved by the fourth week, suggesting an adaptive or recovery response of the skin barrier [

20]. In contrast, the persistent erythema observed in the 1.0 mL group suggests a more sustained irritant effect, likely due to higher local oxidative reactivity or slower barrier repair. These findings are consistent with previous reports that hypochlorite compounds can disrupt stratum corneum integrity, induce inflammation, and enhance dermal reactivity, particularly in unregulated cosmetic preparations [

21].

Dermal exposure to calcium hypochlorite cream caused significant oxidative disruption, reflected by reduced activities of catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) across all doses. Both enzymes serve as primary defenses against reactive oxygen species (ROS); therefore, their suppression suggests overwhelming oxidative load following percutaneous absorption of hypochlorite-derived oxidants. The dose-independent decline in SOD and the substantial reduction in CAT activity highlight the strong pro-oxidant potential of the cream even at low concentrations [

22].

Although MDA levels did not rise significantly, the downward trend in GSH and the marked depletion observed at the 0.3 mL dose support the presence of oxidative stress. The relatively unchanged MDA levels may reflect either early-stage oxidative insult or effective compensatory repair mechanisms preventing lipid peroxidation from progressing to measurable levels. Nonetheless, the collective reduction of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants demonstrates a compromised systemic redox balance. These findings corroborate earlier studies showing that hypochlorite exposure can generate hypochlorous acid and other ROS that rapidly deplete antioxidant reserves, disrupt cellular homeostasis, and predispose tissues to oxidative injury [

23].

The elevation of blood glucose levels across all treatment groups indicates that topical calcium hypochlorite exposure exerts a metabolic impact beyond the skin. The highest glucose concentration occurred in the 0.1 mL group, with a slight decline observed at higher doses. This non-linear pattern may be explained by variable absorption rates, differential inhibition of metabolic enzymes, or physiological compensation at higher concentrations [

24].

Hyperglycaemia in the treated rabbits may arise from ROS-mediated interference with insulin receptor signaling, reduced glucose uptake by peripheral tissues, or stress-related activation of counter-regulatory hormones. Hypochlorite compounds are known to oxidise protein thiol groups, potentially impairing insulin action and contributing to metabolic dysregulation. The present findings align with evidence linking oxidative stress to impaired glucose handling and insulin resistance [

25].

The observed alterations in liver function biomarkers following topical application of the calcium hypochlorite-containing cream indicate that dermal exposure to this formulation has the potential to elicit systemic hepatic effects. The pattern of enzyme changes across doses suggests a complex interaction between percutaneous absorption, oxidative stress, and adaptive hepatic responses [

26].

The increases in AST and ALT at the lower and intermediate doses are indicative of hepatocellular stress or mild injury [

16,

19]. Both enzymes are released into the bloodstream when hepatic cell membrane integrity is compromised, and their elevation is consistent with the oxidative stress profile documented in this study. The highest levels of AST and ALT occurred at the 0.3 mL dose, suggesting that this concentration may represent the point at which dermal absorption and systemic circulation of calcium hypochlorite or its oxidative by-products are maximized. The subsequent decline in enzyme levels at the highest dose (1.0 mL) may reflect reduced dermal penetration, possibly due to the saturation of skin permeability or increased local irritation leading to thicker barrier formation. Alternatively, enhanced hepatic adaptive mechanisms at higher exposure levels cannot be ruled out.

The ALP profile further supports the possibility of hepatic and hepatobiliary stress. While only a mild increase was observed at the lowest dose, the sharp rise at 0.3 mL suggests disturbances in membrane transport processes or bile duct activity [

27]. Elevated ALP is often associated with cholestatic stress and increased hepatobiliary workload [

28]. The decline toward baseline at 1.0 mL again reflects the non-linear, dose-dependent nature of the systemic response, reinforcing the hypothesis that intermediate doses produced the most optimal conditions for hepatic exposure.

Albumin levels showed a different trend from the enzyme markers. The slight decrease at 0.1 mL suggests early suppression of hepatic synthetic function or increased protein utilization under oxidative stress. However, the significant increases in albumin at the 0.3- and 1.0-mL doses may represent compensatory upregulation of protein synthesis or haemo-concentration due to stress-related physiological shifts. Elevated albumin may also reflect an adaptive response to counteract oxidative injury, as albumin plays a role in antioxidant defense and toxin binding [

29]. These findings suggest that calcium hypochlorite, even when administered by a dermal route, can elicit measurable hepatic responses, likely mediated through oxidative stress and systemic absorption of reactive species. The non-linear dose-response pattern observed across the biomarkers aligns with similar findings in toxicology studies where intermediate doses yield maximal systemic effects, possibly due to variations in dermal absorption kinetics. The decline in enzyme levels at the highest dose may reflect limited percutaneous transport or adaptive detoxification pathways triggered by sustained exposure. Overall, the results highlight the potential hepatotoxic risk associated with the use of calcium hypochlorite-containing cosmetic or skin-lightening formulations, particularly those produced without regulatory oversight. These findings underscore the need for stricter monitoring of such products and further research to elucidate long-term hepatic effects, mechanisms of percutaneous absorption, and pathways underlying the observed non-linear dose responses.

Altogether, these results suggest that calcium hypochlorite-containing creams especially those used for skin lightening pose significant dermatological and systemic risks. The combination of skin irritation, antioxidant depletion, and hyperglycaemia underscores the potential for both local and systemic toxicity following repeated dermal exposure. The findings are particularly relevant in regions where unregulated "organic" or artisanal skin-lightening creams commonly incorporate bleaching agents such as hypochlorite without appropriate safety evaluations.

5. Conclusion

This study provides evidence that even low-dose topical exposure to calcium hypochlorite can disrupt oxidative and metabolic homeostasis while inducing varying degrees of skin irritation. These findings highlight the need for stricter regulatory oversight and public health education to reduce the use of potentially harmful skin-lightening products.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analysed during the course of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors of this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Mujtaba SF, Masih AP, Alqasmi I, Alsulimani A, Khan FH, Haque S. Oxidative-Stress-Induced Cellular Toxicity and Glycoxidation of Biomolecules by Cosmetic Products under Sunlight Exposure. Antioxidants. 2021; 10(7):1008. [CrossRef]

- Alnuqaydan AM. The dark side of beauty: an in-depth analysis of the health hazards and toxicological impact of synthetic cosmetics and personal care products. Front Public Health. 2024 Aug 26;12:1439027. [CrossRef]

- Paula KB, Carlotto IB, Marconi DF, Ferreira MBC, Grecca FS, Montagner F. Calcium Hypochlorite Solutions - An In Vitro Evaluation of Antimicrobial Action and Pulp Dissolution. Eur Endod J. 2019 Jan 10;4(1):15-20. [CrossRef]

- Elekhnawy, E., Sonbol, F., Abdelaziz, A. Ebanna T. Potential impact of biocide adaptation on selection of antibiotic resistance in bacterial isolates. Futur J Pharm Sci 6, 97 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bastiansz A, Ewald J, Rodríguez Saldaña V, Santa-Rios A, Basu N. A Systematic Review of Mercury Exposures from Skin-Lightening Products. Environ Health Perspect. 2022 Nov;130(11):116002. [CrossRef]

- Juliano CCA. Spreading of Dangerous Skin-Lightening Products as a Result of Colourism: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(6):3177. [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo JO, Onaolapo YA, Akanmu AM, Olayiwola G. Caffeine and sleep-deprivation mediated changes in open-field behaviours, stress response and antioxidant status in mice. Sleep Sci. 2016 Jul-Sep;9(3):236-243. [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ, Nwoha PU. Methyl aspartylphenylalanine, the pons and cerebellum in mice: An evaluation of motor, morphological, biochemical, immunohistochemical and apoptotic effects. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2017 Dec 1;86:67-77.

- Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ. Nutraceuticals and diet-based phytochemicals in type 2 diabetes mellitus: from whole food to components with defined roles and mechanisms. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2020 Jan 1;16(1):12-25.

- Liu Z, Ren Z, Zhang J, Chuang CC, Kandaswamy E, Zhou T, Zuo L. Role of ROS and Nutritional Antioxidants in Human Diseases. Front Physiol. 2018 May 17;9:477. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter RJ, Watts M, Vale JA, Grieve JR, Schep LJ. The clinical toxicology of sodium hypochlorite. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019 May;57(5):303-311. [CrossRef]

- Schivo M, Aksenov AA, Pasamontes A, Cumeras R, Weisker S, Oberbauer AM, Davis CE. A rabbit model for assessment of volatile metabolite changes observed from skin: a pressure ulcer case study. J Breath Res. 2017 Jan 9;11(1):016007. [CrossRef]

- Ponphaiboon J, Limmatvapirat S, Limmatvapirat C. Development and Evaluation of a Stable Oil-in-Water Emulsion with High Ostrich Oil Concentration for Skincare Applications. Molecules. 2024 Feb 23;29(5):982. [CrossRef]

- LeFors JE, Anderson LM, Hanson MA, Raiciulescu S. Assessment of 2 Hair Removal Methods in New Zealand White Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2022 May 1;61(3):296-303. [CrossRef]

- Derelanko, M.J. (2000). Toxicologist's Pocket Handbook (1st ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ, Adewole SA. Ethanolic extract of Ocimum grattissimum leaves (Linn.) rapidly lowers blood glucose levels in diabetic Wistar rats. Maced J Med Sci. 2011 Dec 1;4(4):351-7.

- Olofinnade AT, Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ, Olowe OA. The potential toxicity of food-added sodium benzoate in mice is concentration-dependent. Toxicology Research. 2021 May;10(3):561-9.

- Stefanucci A, Marinaccio L, Llorent-Martínez EJ, Zengin G, Bender O, Dogan R, Atalay A, Adegbite O, Ojo FO, Onaolapo AY, Onaolapo OJ. Assessment of the in-vitro toxicity and in-vivo therapeutic capabilities of Juglans regia on human prostate cancer and prostatic hyperplasia in rats. Food Bioscience. 2024 Feb 1;57:103539.

- Onaolapo OJ, Adekola MA, Azeez TO, Salami K, Onaolapo AY. l-Methionine and silymarin: A comparison of prophylactic protective capabilities in acetaminophen-induced injuries of the liver, kidney and cerebral cortex. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 Jan;85:323-333. [CrossRef]

- Chung I, Ryu H, Yoon SY, Ha JC. Health effects of sodium hypochlorite: review of published case reports. Environ Anal Health Toxicol. 2022 Mar;37(1):e2022006-0. [CrossRef]

- Goffin V, Piérard GE, Henry F, Letawe C, Maibach HI. Sodium hypochlorite, bleaching agents, and the stratum corneum. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1997 Aug;37(3):199-202. [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska J, Długosz A, Czarnecki D, Tomaszewicz W, Błaszak B, Szulc J, Wróblewska W. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Skin Disorders Associated with Alcohol Dependency and Antioxidant Therapies. Molecules. 2025 Jul 25;30(15):3111. [CrossRef]

- Cordiano R, Di Gioacchino M, Mangifesta R, Panzera C, Gangemi S, Minciullo PL. Malondialdehyde as a Potential Oxidative Stress Marker for Allergy-Oriented Diseases: An Update. Molecules. 2023 Aug 9;28(16):5979. [CrossRef]

- Song G, Liu X, Lu Z, Guan J, Chen X, Li Y, Liu G, Wang G, Ma F. Relationship between stress hyperglycaemic ratio (SHR) and critical illness: a systematic review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025 May 2;24(1):188. [CrossRef]

- Yi Y, Sun X, Liang B, He N, Gibson-Corley KN, Norris AW, Engelhardt JF, Uc A. Acute pancreatitis-induced islet dysfunction in ferrets. Pancreatology. 2021 Aug;21(5):839-847. [CrossRef]

- Anderson SE, Meade BJ. Potential health effects associated with dermal exposure to occupational chemicals. Environ Health Insights. 2014 Dec 17;8(Suppl 1):51-62. [CrossRef]

- Maris BR, Grama A, Pop TL. Drug-Induced Liver Injury—Pharmacological Spectrum Among Children. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(5):2006. [CrossRef]

- Lowe D, Sanvictores T, Zubair M, et al. Alkaline Phosphatase. [Updated 2023 Oct 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459201/.

- Watanabe K, Kinoshita H, Okamoto T, Sugiura K, Kawashima S, Kimura T. Antioxidant Properties of Albumin and Diseases Related to Obstetrics and Gynecology. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(1):55. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).