1. Introduction

Neurotoxicity refers to damage to the nervous system caused by biological, chemical, or physical agents, often resulting in impaired neuronal function and disturbances in cognition, motor activity, and sensory processing [

1]. Contributing factors include environmental pollutants, heavy metals, therapeutic drugs, and endogenous toxins [

2]. Some pharmacological agents, though therapeutically useful, may exert adverse neurologic or neurotoxic effects when administered at high doses or over prolonged periods [

1,

3].

Bromocriptine, an ergot-derived dopamine D2 receptor agonist, is widely used in the management of Parkinson’s disease, hyperprolactinaemia, and acromegaly [

4,

5] Despite its clinical benefits, chronic or high-dose bromocriptine administration has been linked to adverse neurological and psychiatric events [

6,

7]. Reported symptoms include cognitive and behavioural alterations, memory impairment, motor dysfunction, and gastrointestinal disturbances [

6,

7]. Evidence suggests that bromocriptine may affect several brain regions, including the cerebellum—a structure essential for motor coordination, cognitive processing, and emotional regulation [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Growing interest in the benefits of whole food and natural products in the maintenance of health and the mitigation of disease [

8,

9,

10] has led to increased research into the benefits of plant bioactive compounds like quercetin with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in the management of neurotoxicity [

11,

12,

13].

Quercetin a dietary flavonoid abundant in fruits, vegetables, and grains has gained prominence [

14,

15]. Quercetin exhibits potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties, reduces oxidative stress, modulates neuroinflammation, and supports mitochondrial function [

14,

15], all of which are central to preventing neurotoxic injury. Its ability to cross the blood–brain barrier further enhances its therapeutic relevance [

16,

17,

18]. Although quercetin has been studied in various models of neurodegeneration, its protective effect against bromocriptine-induced cerebellar toxicity remains insufficiently defined.

This study therefore investigated quercetin’s neurobehavioural, biochemical, and neuromorphological effects in Wistar rats exposed to bromocriptine. Specifically, we evaluated its impact on body weight, food intake, and novelty-induced behaviours in the open field test, as well as its effects on lipid peroxidation, total antioxidant capacity, and inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α). Additionally, we examined quercetin’s ability to ameliorate bromocriptine-induced histological alterations in the cerebellum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Drugs

Bromocriptine (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, USA), Quercetin (1000 mg, MRM Nutrition, USA), Normal Saline, Assay kits for lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde), interleukin-10, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF α) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (Biovision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA).

2.2. Animals

Healthy Wistar rats utilised in this study were sourced from Empire Breeders, located in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Rats were housed in hardwood cages measuring 20 x 10 x 12 inches at room temperature (25 °C ±2.5 °C), with lights on at 7:00 am and off at 7 pm. Rats were granted unrestricted access to feed and water. All procedures were executed in compliance with the protocols of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, adhering to the regulations for animal care and use outlined in the European Council Directive (EU2010/63) on scientific procedures involving living animals.

2.3. Experimental Methodology

Sixty male Wistar rats (120–150 g each) were randomly assigned into six groups (n = 10). Groups A (Control) were fed standard rat chow and were given oral normal saline (10 ml/kg), Group B and C (Quercetin Control) received quercetin-supplemented chow (500 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg respectively) and oral saline. Rats in Group D (bromocriptine control) were fed standard chow with bromocriptine administered orally at 5 mg/kg [

4], while animals in groups E and F received quercetin-supplemented chow (500 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg respectively) and bromocriptine orally. Drug administration was for 24 days via the oral route. Concentration of quercetin was based on previous studies [

11,

12,

14]. After treatment, animals underwent behavioural tests using the open field box. Twenty-four hours post-testing, rats were euthanised by cervical dislocation and blood was drawn for assays of interleukins (IL)-6 and 1β. Brains were excised, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formol-saline, sections of the cerebellum were processed and stained for histological evaluation.

2.4. Estimation of Body Weight and Feed Intake

Feed intake was measured daily, while body weight of animals in all groups was measured weekly using an electronic weighing scale (Mettler Toledo Type BD6000, Switzerland), as previously described [

19,

20]. The percentage change in body weight or feed intake for each animal was then calculated [

19,

20].

2.5. Open Field Novelty Induced Behaviours

Open-field responses in rats assessed arousal, inhibitory, and inspective exploratory behaviours, as well as anxiety behaviours. Stereotypic behaviours including grooming, have also been measured using this paradigm. These behaviours are typically considered fundamental and signify a rodent’s capacity for exploration. Ten minutes of behaviours in the open field, including grooming, rearing, and horizontal locomotion, were observed and recorded in the open field apparatus as previously described [

21,

22] The open-field paradigm consisted of a square enclosure with a rigid floor, measuring 36 x 36 x 26 cm. The wood was painted white, and the floor was segmented by permanent blue markings into 16 equal squares. Horizontal locomotion (number of floor units traversed by all paws), rearing frequency (number of instances the rat stood on its hind legs, either with its forelimbs against the walls of the observation cage or freely in the air), and grooming frequency (number of body-cleaning actions involving paws, licking of the body and pubis with the mouth, and face-washing behaviours indicative of stereotypic activity) within a 10-minute period were documented as previously described [

21,

22].

2.6. Y Maze Spatial Working Memory

The Y-maze spatial working memory test relies on the innate tendency of rodents to investigate unfamiliar surroundings. The apparatus consists of a wooden maze with three identical arms positioned at 120° angles, forming a “Y” shape. Each arm typically measures about 15 inches in length and 3.5 inches in width, with walls approximately 3 inches high. Each rat was introduced into one arm of the maze and allowed to explore freely, moving from one arm to another once its tail had fully entered the next arm. The order in which the arms were entered was recorded as previously described. [

23,

24].

2.7. Biochemical Test

2.7.1. Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation levels were assessed by determining the malondialdehyde content, which assays the levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substance in samples. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance combine with free malondialdehyde present in samples to form a coloured complex; the concentration of which is expressed as μmol [

25,

26].

2.7.2. Antioxidant Status

Total antioxidant capacity was measured using the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity Assay that is based on the ability of antioxidants within a sample to react with oxidised products as previously described by [

12,

27].

2.7.3. Interleukin (IL)-1β and Interleukin-6

Interleukin (IL)-1β and Interleukin-6 levels were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay methods with commercially available kits procured from Biovision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA.

2.8. Tissue Histology

Rat brains were dissected, sectioned and fixed in neutral-buffered formolsaline. The cerebellum was then processed for paraffin-embedding, cut at 5 μm and stained with haematoxylin and eosin and cresyl fast violet for general histological study [

28].

2.9. Photomicrography

Histological slides of the cerebellum were examined under an Olympus binocular light microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PowerShot 2500 Digital camera.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed using Chris Rorden’s ANOVA for Windows (version 0.98). Analysis of data was by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post-hoc test (Tukey HSD) was used. All results were expressed as mean ± S.E.M and p < 0.05 was taken as the accepted level of significant difference from control.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Quercetin on Body Weight and Feed Intake

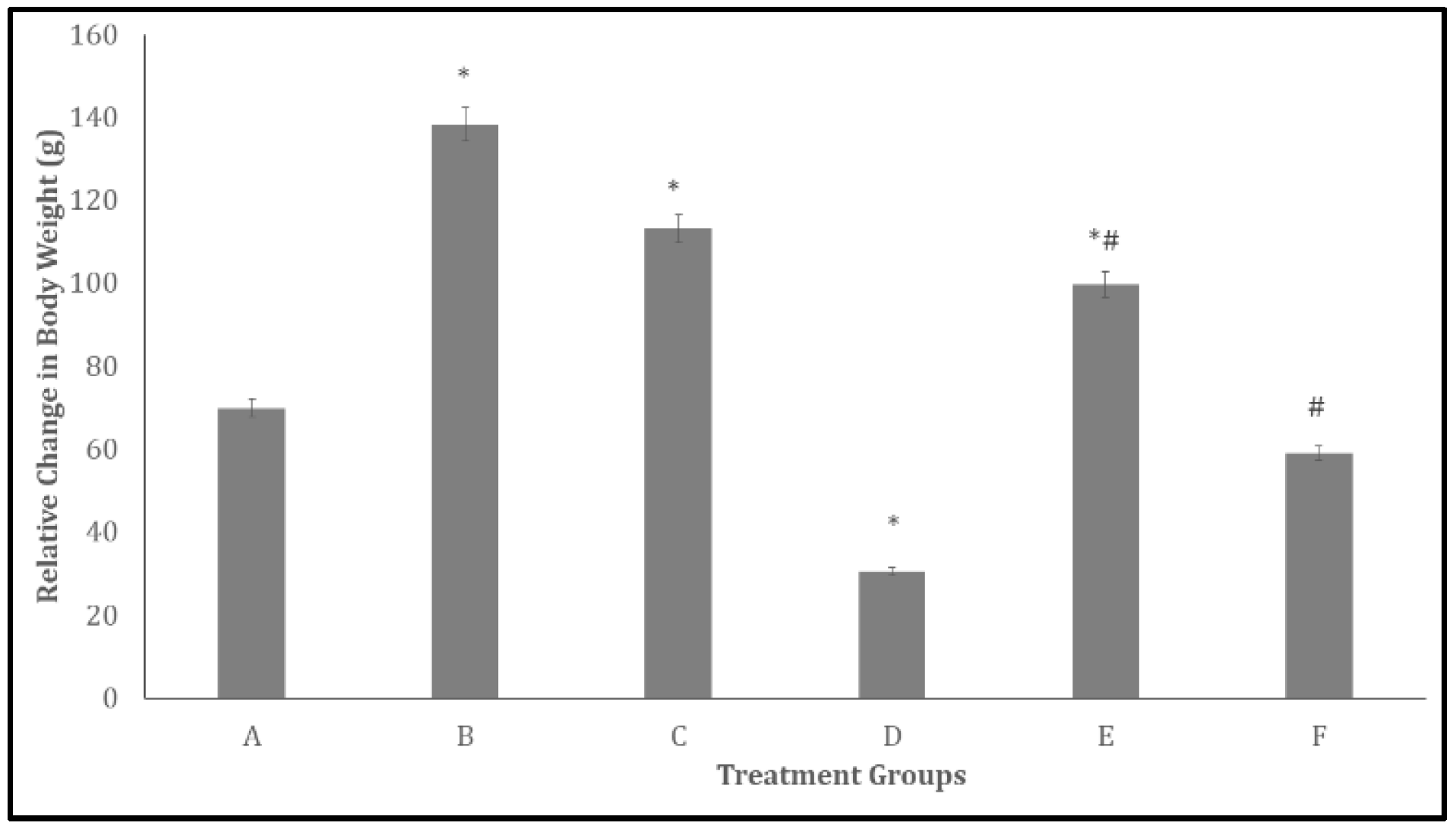

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the effects of quercetin on relative changes in body weight and feed intake, respectively, in bromocriptine-treated rats. As shown in

Figure 1, body weight increased significantly (p < 0.05) in groups B, C, and E, while a significant decrease was observed in group D compared with the control. Relative to group D, body weight was significantly higher in groups E and F.

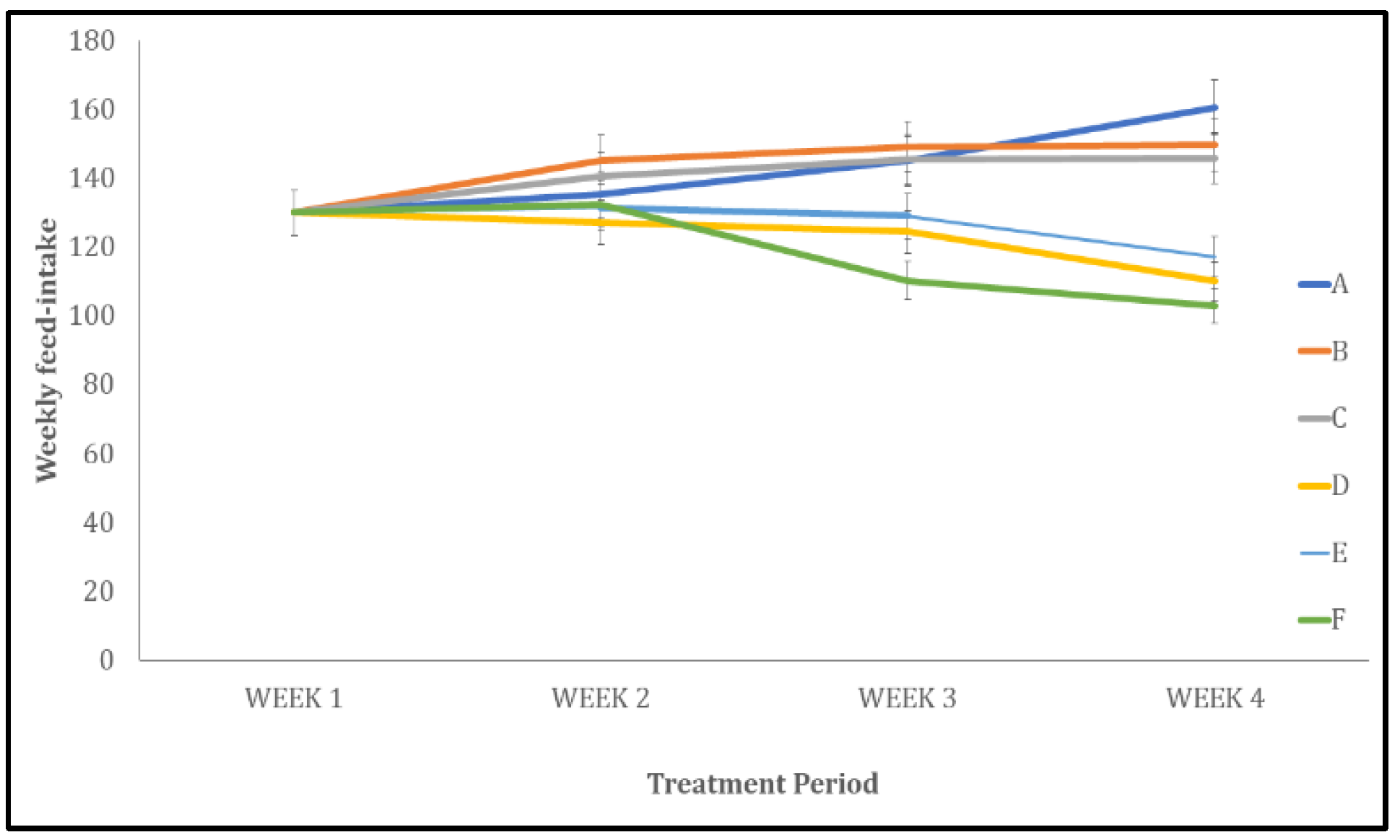

In

Figure 2, feed intake decreased significantly (p < 0.05) across all treated groups (B, C, D, E, and F) compared with the control group (A).

3.2. Effect of Quercetin on Exploratory Behaviours in the Open-Field Box

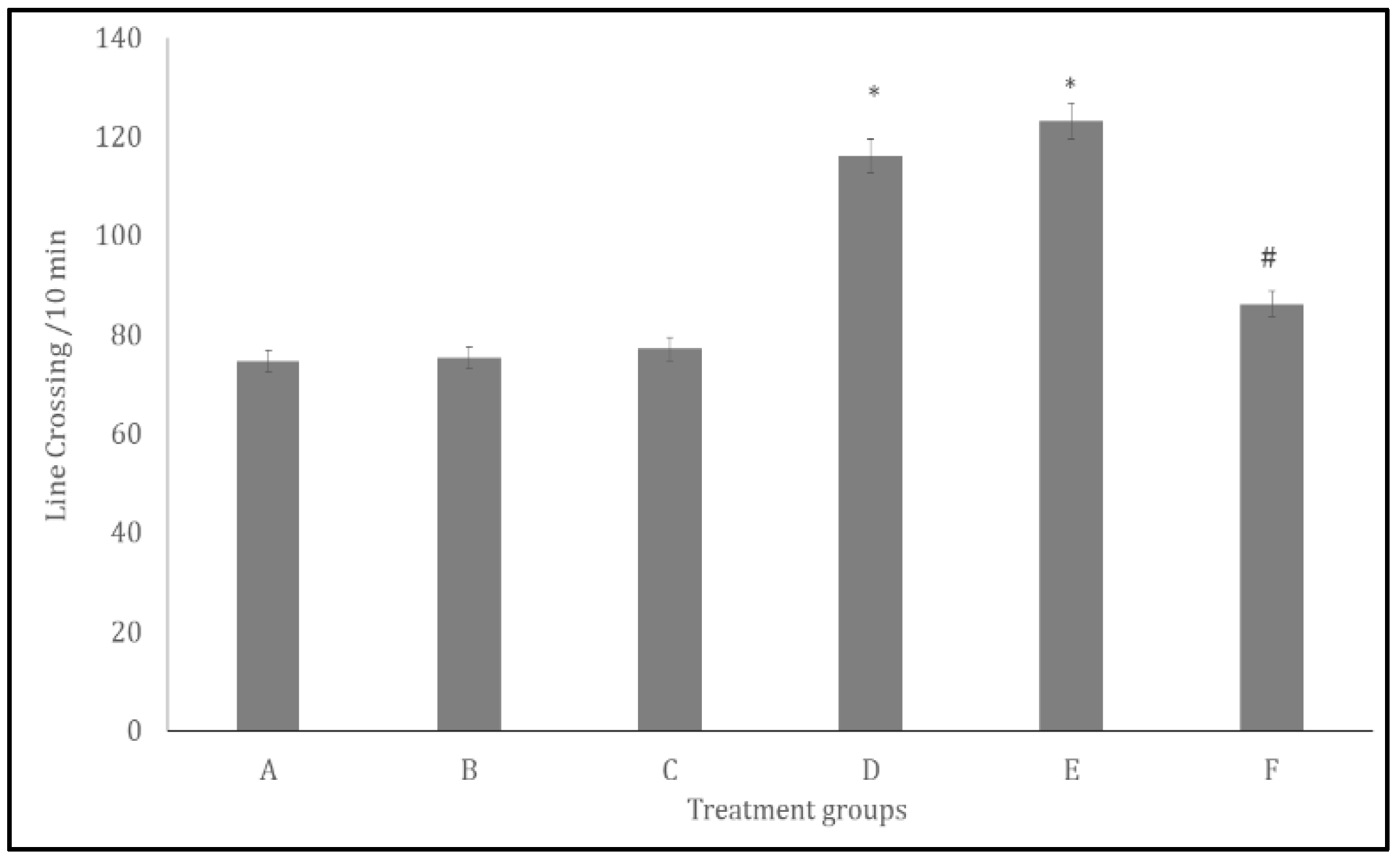

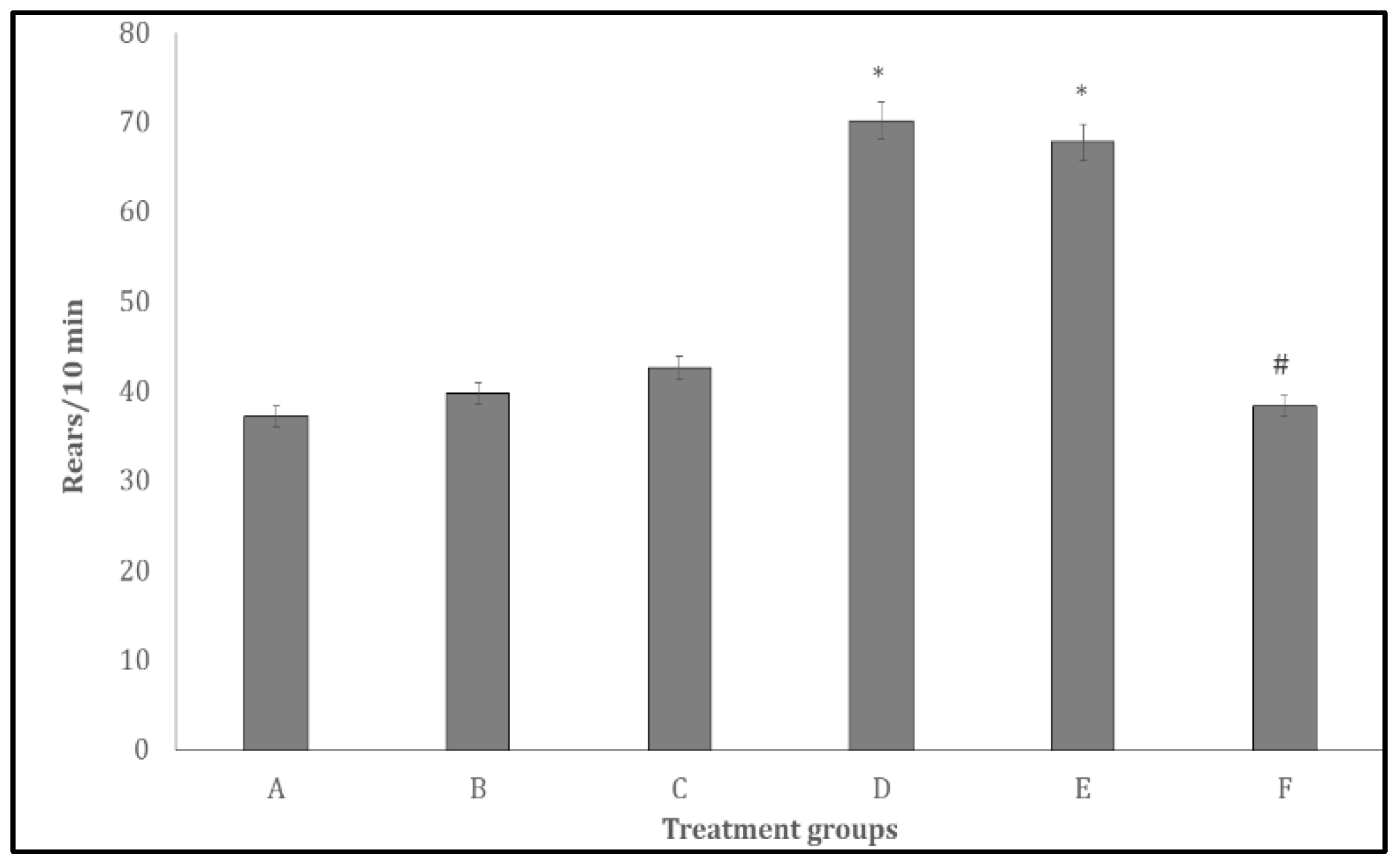

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the effects of quercetin on horizontal locomotion and rearing activity respectively, in bromocriptine-treated rats.

Figure 3 presents the effect of quercetin on horizontal locomotor activity, measured as the number of line crossings during a 10-minute period. There was a significant increase (p < 0.005) in locomotor activity in groups D and E compared with the control group (A). However, compared with group D, locomotor activity decreased in group F.

Figure 4 shows the effect of quercetin on rearing activity, measured as the number of rearings during a 10-minute period. Rearing activity increased significantly (p < 0.005) in groups D and E compared with the control group (A). In contrast, rearing activity decreased in group F relative to group D.

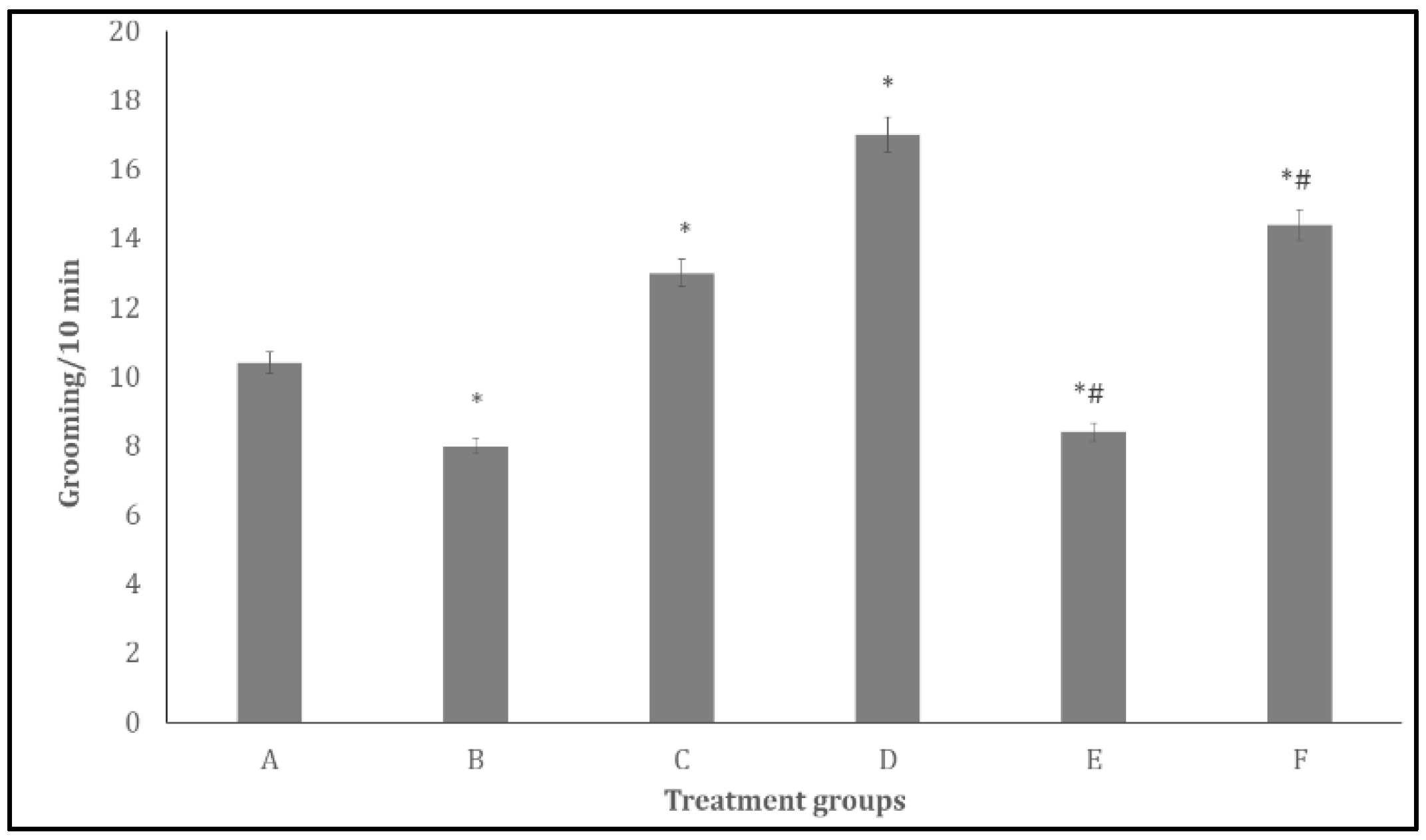

3.3. Effect of Quercetin on Self-Grooming Behaviour

Figure 5 shows the effect of quercetin on self-grooming behaviours in bromocriptine treated rats. There was a significant decrease (p<0.05) in self-grooming in groups B and E and a significant increase in C, D and F compared to A. Compared to D, there was a significant decrease in self- grooming in the groups E and F.

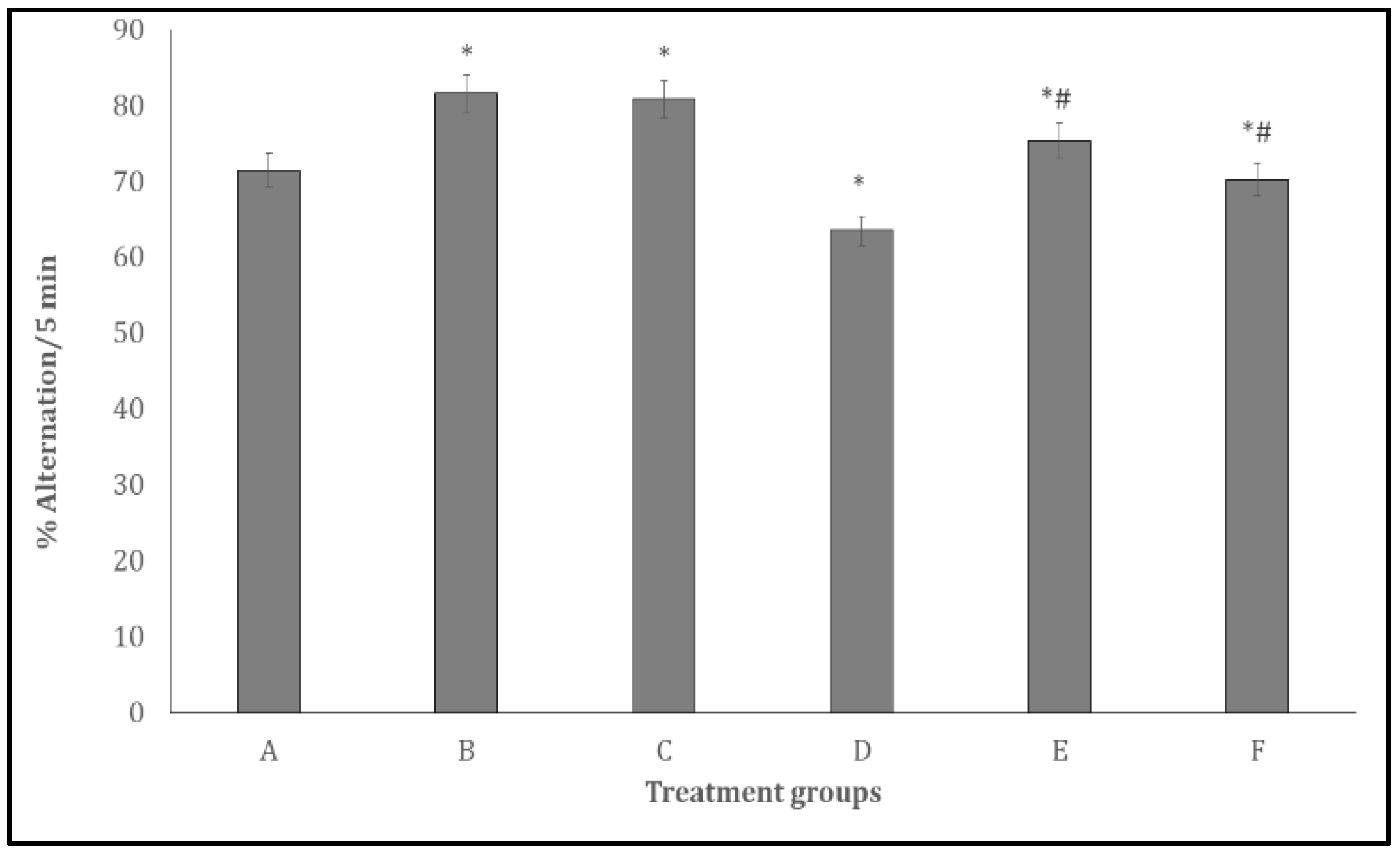

3.4. Effect of Quercetin on Y Maze Spatial Working Memory

Figure 6 shows the effect of quercetin on spatial working memory in the Y- maze. Spatial working memory scores measured as % alternation/5 min increased significantly (p < 0.001) in groups B, C, D and E and decreased significantly in group D compared to group A. Compared to D, working memory scores increased significantly in groups E and F.

3.5. Effect of Quercetin on Oxidative Stress Parameters and Inflammatory Cytokines

Table 1 shows the effect of quercetin on oxidative stress parameters and levels of inflammatory cytokines in bromocriptine treated rats. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased significantly (p < 0.001) in groups C and decreased in groups E and F compared to A. Compared to D, MDA levels decreased significantly in groups E and F.

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) increased significantly (p < 0.001) in groups B, C, E and F and decreased in group D compared to A. Compared to D, TAC levels increased significantly in groups E and F.

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α decreased in groups B and C and increased in groups D, E and F compared to A. Compared to D, TNF- α decreased in groups E and F.

Interleukin (IL)-10 increased significantly (p < 0.001) in groups B, C and E and decreased in group D compared to A. Compared to D, IL-10 levels increased significantly in groups E and F.

Interleukin (IL)-6 decreased in groups B, C, E and F and increased in groups D compared to A. Compared to D IL-6 decreased in groups E and F.

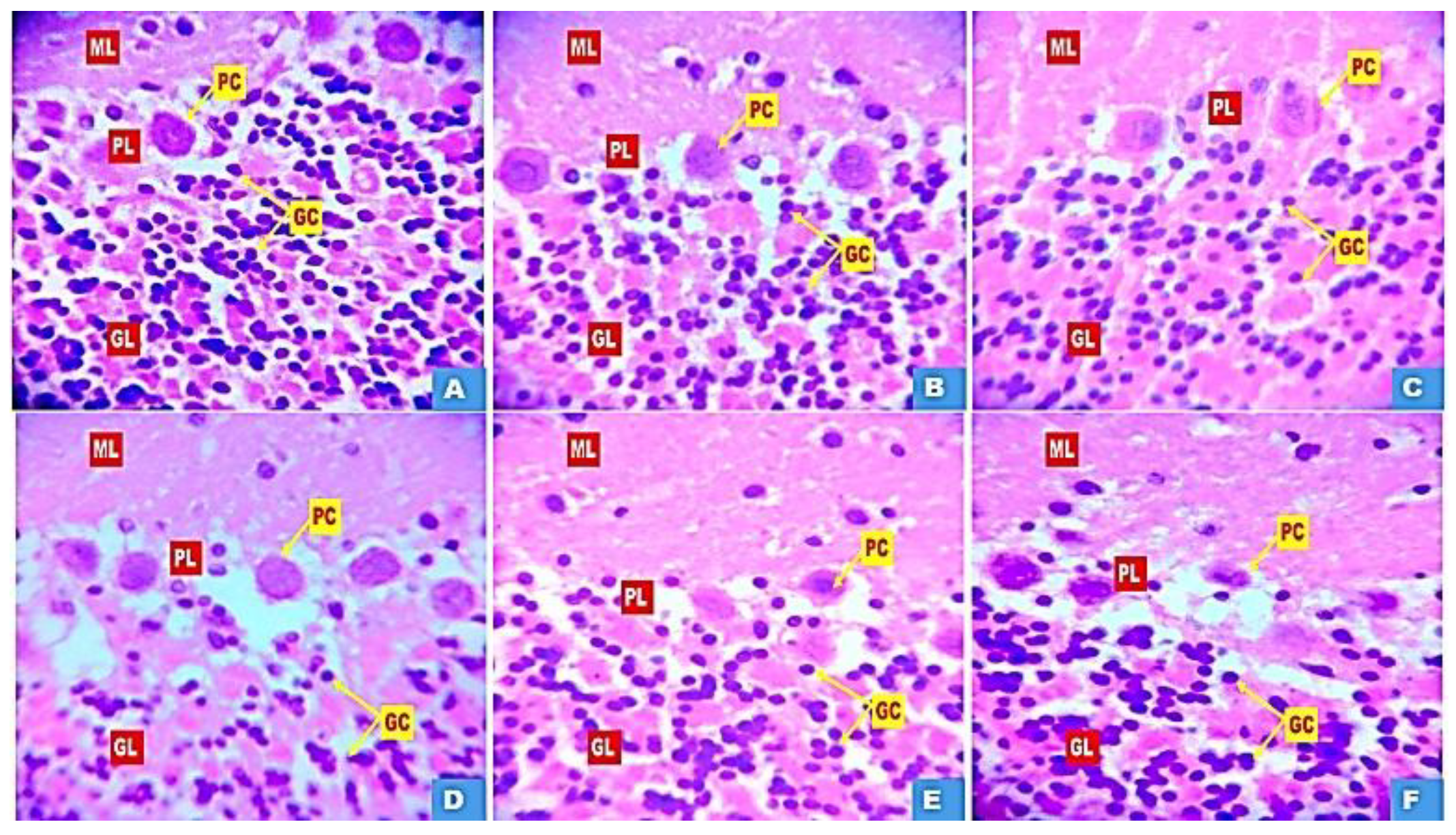

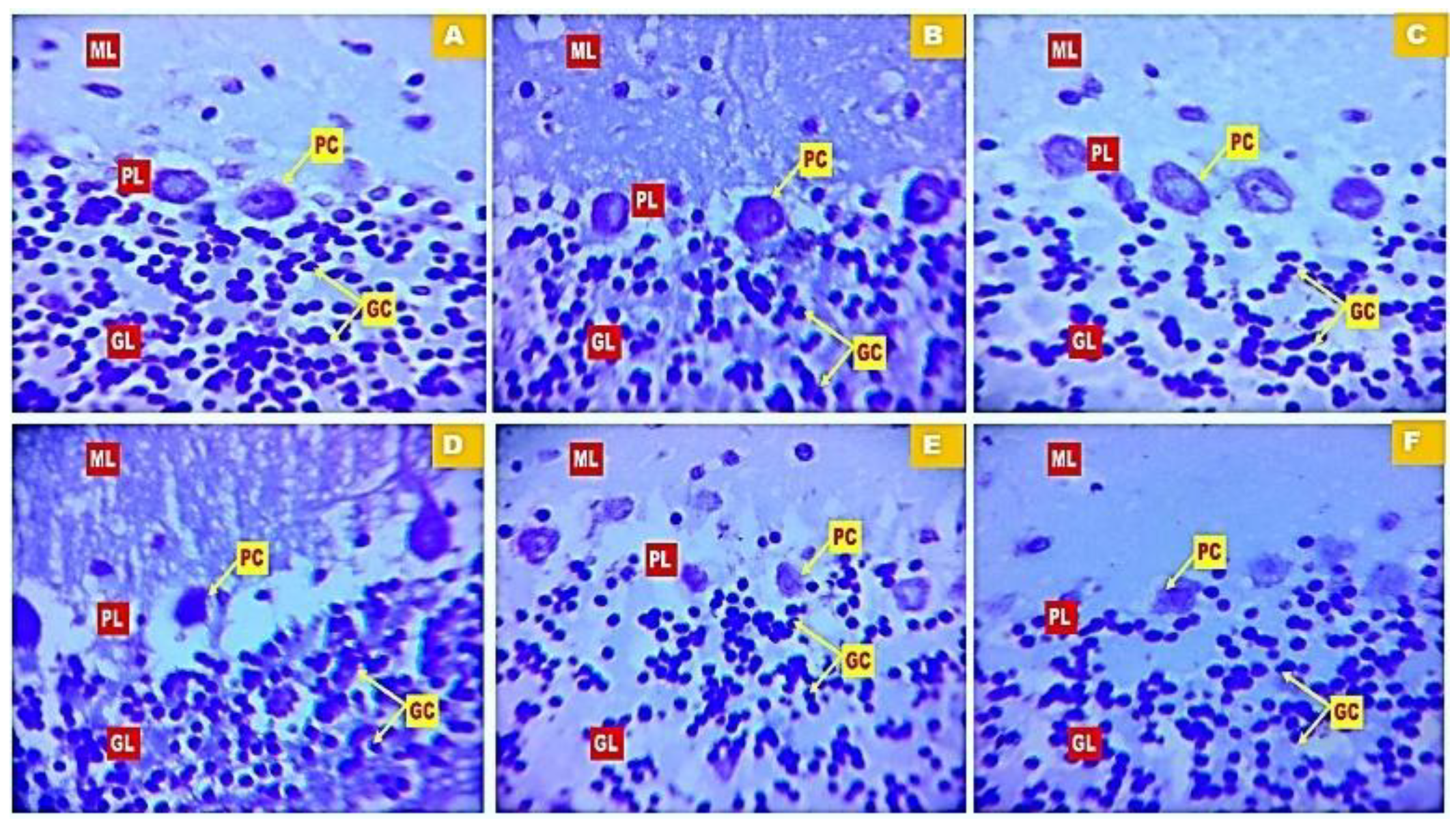

3.6. Effect of Quercetin on the Cerebellar Cortex Histomorphology

Figure 7 (A-F) and

Figure 8 (A-F) show representative photomicrographs of haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and cresyl fast violet (CFV) stained sections of the rat cerebellar cortex respectively. Examination of the H&E-stained slides of rats in group A, B and C revealed distinct layers of the cerebellar cortex showing multiple granule cells in the granule cell layer, large Purkinje cells in the Purkinje cell layer and numerous stellate cells in the Molecular layers. Examination of the cerebellar cortex of rats in the bromocriptine control (group D) revealed widespread vacuolation in the molecular layer and around individual Purkinje cells. There was also wide dispersal of the granule cells in the granular layer, coupled with shrinkage of the Purkinje cells. Examination of CFV stained sections of the rat cerebellar cortex in groups A, B and C revealed the characteristic layered arrangement of the cerebellum with prominent Nissl bodies and clear neuropil. Group D showed degeneration with disrupted Nissl substance. However, in the H&E and CFV stained sections of the rat cerebellum in groups E and F varying degrees of reversal of bromocriptine-induced cerebellar cortex neurodegeneration was observed.

4. Discussion

This study examined the possible neuroprotective effects of quercetin in Wistar rats with bromocriptine-induced changes in the rat cerebellum. Bromocriptine has been suggested to generally have neuroprotective effects and has been used widely in the management of Parkinson’s disease [

29], with research also suggesting that it could be beneficial in traumatic brain injury [

30]. However, a few studies have reported evidence of bromocriptine-behavioural and structural changes following prolonged administration or when high doses are administered [

4,

5,

31]. In this study the administration of bromocriptine impaired weight gain and feed intake, decreased exploratory behaviours, impaired memory, promoted oxidative stress and neuroinflammation and caused neuronal injury. Treatment with quercetin ameliorated these effects, highlighting its neuroprotective potential.

Bromocriptine treatment in this study was associated with significant reductions in body weight and feed intake, consistent with earlier reports [

4,

33]. Bromocriptine is a dopamine D2 receptor agonist that has been shown to modulate central nervous system pathways that regulate glucose and energy metabolism [

34]. In groups treated with quercetin a reversal of bromocriptine -induced changes in body weight and feed intake were observed consistent with the result of previous studies [

11,

12,

14]. Quercetin’s ability to restore changes in body weight and feeding patterns suggests improved metabolic balance and overall health in the treated animals, supporting the therapeutic value of quercetin. The therapeutic value of quercetin use appear to be heavily dependent on dosage, the duration of the intervention, the experimental model used, and the initial health status of the subjects; with studies on obese animals showing more pronounced effects than those using healthy subjects [

34,

35].

Behavioural assessments revealed that bromocriptine markedly impaired locomotion and self-grooming, and induced anxiety-like behaviour consistent with our previous study [

4]. This is likely linked to bromocriptine’s interference with dopaminergic and cholinergic signaling, as dysfunction within these pathways is closely associated with deficits in motor coordination and self-maintenance behaviours [

36]. Quercetin, possibly through its strong antioxidant properties, facilitated the recovery of motor functions and reversed memory loss, consistent with findings from previous research [

37].

In addition, bromocriptine significantly increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, in agreement with earlier studies showing elevated TNF-α, and IL-6, and decreased IL-10 following bromocriptine treatment [

6]. Quercetin effectively attenuated these increases, aligning with previous observations of its anti-inflammatory effects [

12]. A few studies have reported the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of bromocriptine [

38], however, at the dose administered in this study, bromocriptine was associated with decreased antioxidant status and increased oxidative stress, characterised by alterations in TAC and MDA levels. By inhibiting the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and suppressing microglial inflammatory gene expression, quercetin reduced both neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [

17].

Histomorphological studies using H&E and Cresyl Fast Violet staining further supported these biochemical and behavioural observations. Bromocriptine-treated rats exhibited marked cortical degeneration, including neuronal shrinkage, pyknotic nuclei, and loss of Nissl substances, features indicative of compromised protein synthesis and neuronal dysfunction. In contrast, quercetin administration preserved cortical architecture, restoring normal pyramidal cell morphology and the presence of Nissl bodies. These findings collectively suggest that quercetin affords robust neuroprotection and promotes structural recovery following bromocriptine-induced neuronal injury.

Overall, the results of this study demonstrate that quercetin confers significant neuroprotective benefits against bromocriptine-induced neurotoxicity. Its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms help safeguard motor behaviour, cognitive function, and neuronal integrity.

5. Conclusions

Quercetin administration markedly alleviated the behavioural, biochemical, and histological impairments associated with bromocriptine. Improvements in open-field behaviours, such as enhanced locomotion and reduced spatial working memory, together with the preservation of cerebellar cortical integrity, underscore its therapeutic potential. By targeting oxidative stress and inflammatory dysregulation, quercetin offers a comprehensive neuroprotective approach that may be useful in addressing neurodegenerative conditions driven by these mechanisms. These findings support the potential of quercetin as a viable intervention for mitigating neurotoxicity-related behavioural and cognitive deficits and highlight the importance of integrative therapeutic strategies in neuroprotection.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences (ERC/FBMS/099/2025).

Data Availability Statement

Data generated during and analysed during the course of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors of this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J. Nevirapine mitigates monosodium glutamate induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress changes in prepubertal mice. Ann Med Res. 2018, 25, 518–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, S.; Sahoo, C.R.; Iqubal, M.K.; Haque, S.E. Environmental neurotoxic pollutants: review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020, 27, 41175–41198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Onaolapo, A.Y.; Okunola, O.B.; Onaolapo, O.J. Zinc Gluconate Supplementation Protects against Methotrexate-induced Neurotoxicity in Rats via Downregulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Neuron-specific Enolase Reactivity in Rats. Current Biotechnology. 2024, 13, 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Subchronic Oral Bromocriptine Methanesulfonate Enhances Open Field Novelty-Induced Behavior and Spatial Memory in Male Swiss Albino Mice. Neurosci J. 2013, 2013, 948241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozery, M.; Wadhwa, R. Bromocriptine. [Updated 2024 May 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555948/.

- Naz, F.; Malik, A.; Riaz, M.; Mahmood, Q.; Mehmood, M.H.; Rasool, G.; Mahmood, Z.; Abbas, M. Bromocriptine therapy: Review of mechanism of action, safety and tolerability. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2022, 49, 903–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, I. Non-reproductive triggers of postpartum psychosis. Arch Women’s Ment Health Erratum in Arch Women’s Ment Health 2017, 20, 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0699-0. 2017, 20, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J. Nutraceuticals and diet-based phytochemicals in type 2 diabetes mellitus: from whole food to components with defined roles and mechanisms. Current Diabetes Reviews 2020, 16, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.R. (Ed.) . Natural molecules in neuroprotection and neurotoxicity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J. Herbal beverages and brain function in health and disease. In Functional and medicinal beverages; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Ojo, F.O.; Onaolapo, O.J. Biflavonoid quercetin protects against cyclophosphamide–induced organ toxicities via modulation of inflammatory cytokines, brain neurotransmitters, and astrocyte immunoreactivity. Food and chemical toxicology 2023, 178, 113879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Samson, P.O.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Quercetin/Donepezil co-administration mitigates Aluminium chloride induced changes in open field novelty induced behaviours and cerebral cortex histomorphology in rats. Acta Bioscienctia. 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, H.A.; Elfiky, A.M.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Ibrahim, K.S.; Ghazy, M.A. Neuroprotective effect of quercetin through targeting key genes involved in aluminum chloride induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2023, 10, 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofinnade, A.T.; Ajifolawe, O.B.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Dry-feed Added Quercetin Mitigates Cyclophosphamide-induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Gonadal Fibrosis in Adult Male Rats. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2025, 24, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Biedrawa, D.; Grabowska, K.; Galanty, A.; Sobolewska, D.; Podolak, I. A Flavonoid on the Brain: Quercetin as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Central Nervous System Disorders. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, C.; Hamilçıkan, Ş. Neuroprotective Effects of Quercetin in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: A Meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2025, 42, 2203–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.C.; Tsai, T.Y.; Wang, C.J. The Potential Benefits of Quercetin for Brain Health: A Review of Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, I.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar, S. Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in Neuroprotection: A Comprehensive Review of Pathways and Clinical Perspectives. BIOI 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaderu, T.A.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Post-conceptional melatonin administration mitigates changes in neurobehaviour and cerebral cortex histomorphology in prenatal sodium valproate-exposed rats. Acta Bioscientia 2025, 1, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, J.A.; Akinsehinwa, A.F.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Alcohol Extract of Muira Puama (Ptychopetalum Olacoides) ameliorates Aluminium Chloride-induced changes in Behaviour and Cerebral cortex Histomorphology in Wistar Rats. Acta Bioscienctia 2025, 1, 022–029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Paul, T.B.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Comparative effects of sertraline, haloperidol or olanzapine treatments on ketamine-induced changes in mouse behaviours. Metabolic Brain Disease 2017, 32, 1475–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Acute low dose monosodium glutamate retards novelty induced behaviours in male Swiss albino mice. Neurosc Behav Health. 2011, 3, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Awe, E.O.; Oloyede, S.; Joel, A. Oral amodiaquine, artesunate and artesunate amodiaquine combination affects open field behaviours and spatial memory in healthy Swiss mice. Journal of Behavioural and Brain Science 2013, 3, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Effects of Ginsomin® on selected behaviours in Mice. Int J Neurosci Behav Sci. 2017, 5, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Odeniyi, A.O.; Jonathan, S.O.; Samuel, M.O.; Amadiegwu, D.; Olawale, A.; Tiamiyu, A.O.; Ojo, F.O.; Yahaya, H.A.; Ayeni, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. An investigation of the anti-Parkinsonism potential of co-enzyme Q10 and co-enzyme Q10/levodopa-carbidopa combination in mice. Current Aging Science. 2021, 14, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Diaz De Leon, J.; Borges, C.R. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress in Biological Samples Using the Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances Assay. J Vis Exp. 2020, 159, 10.3791–61122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y. Anxiogenic, memory-impairing, pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory effects of sodium benzoate in the mouse brain. Düşünen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo, A.Y.; Onaolapo, O.J.; Nwoha, P.U. Methyl aspartylphenylalanine, the pons and cerebellum in mice: An evaluation of motor, morphological, biochemical, immunohistochemical and apoptotic effects. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy 2017, 86, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Raymick, J.; Imam, S. Neuroprotective and Therapeutic Strategies against Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munakomi, S.; Bhattarai, B.; Mohan Kumar, B. Role of bromocriptine in multi-spectral manifestations of traumatic brain injury. Chin J Traumatol. 2017, 20, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Song, H.C.; An, H.; Yang, J.; Ko, Y.H.; Jung, I.K.; Joe, S.H. Effect of bromocriptine on antipsychotic drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: eight-week randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010, 64, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhan, M.T.; Ayele, T.M.; Abebe, F.W.; Dgnew, F.N. Effect of bromocriptine on glycemic control, risk of cardiovascular diseases and weight in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, T.; Zabihi, M.; Hoseinzade, F.; Rohani, M.; Saghafi, F. Bromocriptine in type 2 diabetes: a promising alternative, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol Endocrinol Rep. 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liao, D.; Dong, Y.; Pu, R. Clinical effectiveness of quercetin supplementation in the management of weight loss: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Bian, H.X.; Xu, N.; Bao, B.; Liu, J. Quercetin reduces obesity-associated ATM infiltration and inflammation in mice: a mechanism including AMPKα1/SIRT1. J Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 363–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Nasiripour, S.; Bopassa, J.C. Parkinson Disease Signaling Pathways, Molecular Mechanisms, and Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 6416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fideles, S.O.M.; de Cássia Ortiz, A.; Buchaim, D.V.; de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira, E.; Parreira, M.J.B.M.; de Oliveira Rossi, J.; da Cunha, M.R.; de Souza, A.T.; Soares, W.C.; Buchaim, R.L. Influence of the Neuroprotective Properties of Quercetin on Regeneration and Functional Recovery of the Nervous System. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cincotta, A.H.; Cersosimo, E.; Alatrach, M.; Ezrokhi, M.; Agyin, C.; Adams, J.; Chilton, R.; Triplitt, C.; Chamarthi, B.; Cominos, N.; DeFronzo, R.A. Bromocriptine-QR Therapy Reduces Sympathetic Tone and Ameliorates a Pro-Oxidative/Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Plasma of Type 2 Diabetes Subjects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effect quercetin on mean relative change in body weight in rats. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 1.

Effect quercetin on mean relative change in body weight in rats. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 2.

Effect quercetin on mean relative change feed intake (in rats. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 2.

Effect quercetin on mean relative change feed intake (in rats. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 3.

Effect Quercetin on Locomotor activity in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, e: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin a(1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 3.

Effect Quercetin on Locomotor activity in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, e: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin a(1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 4.

Effect Quercetin on Rearing activity in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 4.

Effect Quercetin on Rearing activity in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 5.

Effect Quercetin on self-grooming behaviours in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 5.

Effect Quercetin on self-grooming behaviours in the open field paradigm. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 6.

Effect Quercetin on Y-maze spatial working memory. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 6.

Effect Quercetin on Y-maze spatial working memory. Each bar represents Mean ± S.E.M, *p < 0.05 significant difference from A, #p < 0.05 significant difference from D, number of rats per treatment group =10. A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed).

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of haematoxylin and eosin-stained cerebellar cortex in groups A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed). Showing granule cells (GC) in the granule cell layers (GL), Purkinje cells (PC) in the Purkinje layers (PL) and molecular layers (ML) (Mag. X400).

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of haematoxylin and eosin-stained cerebellar cortex in groups A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed). Showing granule cells (GC) in the granule cell layers (GL), Purkinje cells (PC) in the Purkinje layers (PL) and molecular layers (ML) (Mag. X400).

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph of cresyl fast violet-stained sections of the rat cerebellar cortex in groups A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed). Showing granule cells (GC) in the granular layers (GL), Purkinje cells (PC) in the Purkinje layer (PL). (Mag. X400).

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph of cresyl fast violet-stained sections of the rat cerebellar cortex in groups A: Control B: Quercetin at 500 mg/kg of feed, C: Quercetin at 1000 mg/kg of feed, C: Bromocriptine at 5mg/kg, E: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (500 mg/kg of feed) F: Bromocriptine + Quercetin (1000 mg/kg of feed). Showing granule cells (GC) in the granular layers (GL), Purkinje cells (PC) in the Purkinje layer (PL). (Mag. X400).

Table 1.

Effect of quercetin on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant capacity and inflammatory markers.

Table 1.

Effect of quercetin on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant capacity and inflammatory markers.

| Groups |

MDA (µm) |

TAC (mM TE) |

TNF-α ng/L |

IL-10 pg/ml |

IL-6 pg/ml |

| A |

0.80±0.05 |

10.50±2.66 |

2.37±0.47 |

11.03±0.02 |

5.66±0.46 |

| B |

0.74±0.01 |

14.94±0.34*

|

1.52±0.17*

|

22.43±0.35*

|

4.51±0.48*

|

| C |

0.76±0.01 |

13.95±4.34*

|

2.09±0.53*

|

21.17±0.01*

|

2.64±0.01*

|

| D |

25.27±0.21*

|

5.39±2.89*

|

55.11±0.39*

|

1.19±0.06*

|

8.5±0.41* |

| E |

0.73±0.01*#

|

14.98±3.54#

|

21.41±0.13*#

|

18.53±1.55*#

|

1.85±0.04*#

|

| F |

0.75±0.01*#

|

14.31±0.08*#

|

12.47±0.28*#

|

11.09±0.42#

|

2.03±0.01*#

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).