Introduction

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) play a central role in the European economy, contributing substantially to employment, innovation, and regional development. SMEs generate more than one-fifth of the EU27’s total value-added and provide over 35 million jobs, underscoring their importance for economic resilience and competitiveness [

1]. Despite this significance, SMEs face heightened competitive pressures driven by globalisation, fluctuating market demand, and the rapid digitalisation of industrial value chains [

2]. For manufacturing-oriented SMEs, improving production efficiency is particularly critical, as it directly influences cost structures, delivery performance, and the ability to compete in global markets [

3].

Coopetition, defined as simultaneous collaboration and competition has emerged as a promising strategic approach for resource-constrained firms seeking to enhance operational performance and innovate effectively [

4]. Through coopetitive arrangements, firms share non-core resources, exchange knowledge, and collectively pursue innovation while maintaining competitive differentiation in their focal markets. Yet, despite institutional endorsement and increasing scholarly attention [

5], many SME owners remain reluctant to adopt coopetition strategies due to concerns over trust, knowledge leakage, and governance complexity [

6]. This hesitation limits their capacity to leverage shared capabilities that could directly improve manufacturing efficiency and innovation outcomes [

7].

Existing research establishes the importance of collaboration for enhancing innovation and performance. However, it reveals significant gaps in understanding how coopetition influences concrete manufacturing efficiency outcomes in SMEs, particularly in technology-intensive environments. Much of the coopetition literature remains conceptual, focused on relational dynamics or innovation performance. In contrast, empirical evidence on direct operational impacts, such as productivity, material efficiency, and output quality, remains scarce [

8]. Furthermore, the role of digital technologies as structural enablers of coopetition is underexplored. In particular, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) offers new possibilities for real-time data sharing, resource optimization, and coordinated production processes. However, its potential to support coopetition networks has received limited empirical examination [

9].

Service-Dominant (S-D) Logic provides a useful theoretical lens for addressing these gaps, as it views value creation as a process of integrating resources among multiple actors in a service ecosystem [

10]. From this perspective, coopetition can be understood as a mechanism for value co-creation, in which competing firms integrate digital and organizational resources to improve operational outcomes. Complementing this, Open Innovation highlights the strategic use of external knowledge to enhance internal processes and supports the idea that coopetition facilitates knowledge flows that drive efficiency-enhancing innovation [

11].

Building on these perspectives, this study investigates whether IIoT-enabled coopetition networks improve determinants of manufacturing efficiency in SMEs. Focusing on Portuguese Ornamental Stone SMEs [

12], a sector that is both economically significant and operationally constrained, the research evaluates the effects of transitioning from conventional production practices to a technologically enabled coopetition network. The study examines four key performance indicators: first-time-through quality, performance efficiency, raw material yield, and labour productivity.

The research addresses a central question: Does coopetition improve key determinants of manufacturing efficiency in SMEs by fostering innovation and enhancing resource integration? To answer this, the study tests the hypothesis that participation in IIoT-integrated coopetition networks leads to measurable improvements in operational efficiency and production stability.

By providing empirical evidence from a real-world IIoT-enabled coopetition network, this study contributes to the coopetition, S-D Logic, and Open Innovation literature. It demonstrates how digital infrastructures can support cooperative value creation among competitors and offers practical insights for SMEs and industrial clusters seeking to improve manufacturing efficiency in digitally transformed environments. The findings aim to support both scholars and practitioners in understanding how coopetition and IIoT technologies mutually reinforce each other to enhance competitiveness in traditional manufacturing sectors.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Coopetition in SME Networks

Coopetition has gained prominence as a strategic mechanism for creating mutual value among firms facing resource constraints [

4]. Through cooperative engagement, firms share complementary capabilities, exchange knowledge, and access resources that would otherwise be costly or unavailable, while competition ensures continued differentiation and market agility [

7]. Research highlights that coopetition can enhance innovation, reduce operational redundancies, and unlock market opportunities, particularly within interconnected firm networks [

13].

Despite these advantages, sustaining coopetition remains challenging. The contradictory nature of collaboration and competition generates relational tensions that may undermine network stability if not appropriately managed [

14]. Trust, transparent communication, and shared governance structures are widely recognised as essential to overcoming these tensions, though practical mechanisms for institutionalising these dynamics remain underexplored [

7]. Moreover, the literature lacks empirical evidence on how coopetition directly affects manufacturing efficiency, as most studies focus on innovation or strategic outcomes rather than operational performance metrics relevant to SMEs [

8].

Several theoretical perspectives offer partial insights into coopetition dynamics. Game Theory emphasizes strategic decision-making under competitive constraints but often assumes rationality and information symmetry not found in real-world SME contexts [

15]. The Resource-Based View (RBV) highlights the pooling of complementary resources but overlooks collaborative processes of value co-creation [

16]. Paradox Theory explores tensions as drivers of innovation but provides limited guidance on the operational mechanisms through which tensions translate into efficiency gains [

17]. These perspectives provide useful foundations yet fall short of explaining how coopetition can be structured to generate sustained operational improvements [

14].

These gaps indicate the need for frameworks that integrate relational, operational, and technological dimensions of coopetition. This provides the rationale for adopting S-D Logic and Open Innovation as complementary theoretical lenses.

2.2. Service-Dominant Logic as a Framework for Resource Integration

Service-Dominant Logic reconceptualizes economic exchange as a process of value co-creation [

18], in which actors integrate resources within dynamic service ecosystems [

10]. This perspective aligns closely with coopetition, as both emphasize interactions among multiple actors, resource integration, and collaborative value creation. Under S-D Logic, firms act as “resource integrators,” combining operand resources (e.g., materials, technologies) with operant resources (e.g., knowledge, skills) to produce value-in-use [

19].

Applying S-D Logic to coopetition networks shifts the emphasis from transactional benefits to ongoing, adaptive processes of co-creation supported by institutional arrangements [

20]. Shared norms, rules, and technological infrastructures enable participants to coordinate activities, align mutual interests, and sustain collaboration over time [

21]. This perspective is particularly relevant in digital environments, where continuous resource integration is supported by real-time communication and advanced data systems.

However, empirical applications of S-D Logic to coopetition remain limited, especially in manufacturing settings where physical production efficiency is central. Research frequently addresses value propositions and ecosystem dynamics. However, it does not investigate how S-D Logic mechanisms translate into measurable operational performance, an important gap for SMEs seeking evidence-based justification for coopetition strategies.

2.3. Open Innovation and External Knowledge Integration

Open Innovation complements S-D Logic by emphasizing the intentional use of external knowledge sources to accelerate internal innovation and enhance organizational performance [

22]. For SMEs, external knowledge acquisition, via collaboration, partnerships, or technology exchanges is often critical due to limited internal R&D capacities [

11].

Coopetition is a specific form of open innovation in which competitors collaborate to overcome resource constraints, optimize production processes, and collectively develop innovative solutions [

23]. Prior studies show that such collaborative innovation can improve process efficiency, reduce waste, and support technological upgrading [

24]. However, open innovation literature rarely examines performance indicators tied to day-to-day manufacturing operations, leaving a lack of empirical evidence on how collaborative resource integration impacts production efficiency.

Thus, while Open Innovation highlights the strategic benefits of external knowledge flow, it does not yet fully explain how technology-enabled coopetition contributes to operational efficiency improvements in SMEs.

2.4. IIoT as a Technological Enabler of Coopetition

The IIoT provides an infrastructural foundation for real-time communication, machine interconnectivity, and data-driven decision-making in industrial environments [

25]. By connecting machines, sensors, and production systems, IIoT facilitates real-time monitoring, resource sharing, and production coordination, capabilities essential for effective coopetition networks [

26].

IIoT adoption has been shown to improve production visibility, optimize resource usage, reduce downtime, and enable predictive maintenance [

27]. However, integrating IIoT across multiple firms introduces complexity related to interoperability, cybersecurity, data governance, and trust [

28]. These challenges are particularly salient in coopetition contexts, where competitors must share information while maintaining confidentiality and protecting strategic assets [

29].

Despite IIoT’s transformative potential, research integrating IIoT with coopetition remains scarce [

29]. Few studies investigate how IIoT-enabled networks support collaborative resource integration or how digital infrastructures influence manufacturing efficiency outcomes across interconnected firms. This presents a significant research opportunity, especially for SMEs aiming to leverage digital transformation to enhance competitiveness.

2.5. Research Gaps and Study Contribution

Across the bodies of literature reviewed, coopetition, S-D Logic, Open Innovation, and IIoT, three central gaps emerge: (1) Insufficient empirical evidence on how coopetition impacts operational manufacturing efficiency, particularly in SMEs; (2) limited understanding of digital infrastructures (e.g., IIoT) as enablers of coopetition-driven value co-creation; and (3) lack of integrative frameworks connecting value co-creation (S-D Logic), external knowledge flows (Open Innovation), and real-time resource integration (IIoT).

This study addresses these gaps by examining how an IIoT-enabled coopetition network influences key determinants of manufacturing efficiency, first-time-through quality, performance efficiency, raw material yield, and labour productivity, in Portuguese Ornamental Stone SMEs. By combining theoretical perspectives and real-world data, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of how technology-enabled coopetition enhances operational performance in traditional manufacturing sectors.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a case study research design to empirically examine how a coopetition network enabled by IIoT technologies influences manufacturing efficiency in SMEs [

30]. The case study method is well-suited for analyzing complex socio-technical interactions within real operational environments and enables a detailed comparison between two distinct operational modes: (1) State-of-the-Art Practices (SoAP) – firms operate independently; and (2) Coopetition Network Practices (CnP) – firms operate within a digitally connected coopetition network.

Data were collected across two 54-day observation periods, one for SoAP and one for CnP to evaluate the effects of coopetition on key manufacturing efficiency indicators.

3.2. Sector Context, Population, and Sample

Selecting an appropriate empirical setting is crucial in quantitative research, particularly when data specificity and acquisition costs are high [

31]. For this study, the sector and participating firms were chosen based on feasibility and access to detailed operational data, ensuring a suitable context for examining coopetition and its effects on manufacturing efficiency.

The Portuguese Ornamental Stone (POStone) sector offers an ideal setting. Historically tied to Portugal’s cultural heritage and known for unique geological resources and specialized craftsmanship [

32], the sector has successfully integrated into the global market. It consists mainly of SMEs, generates over 16,600 jobs, exports to 116 countries, and ranks among the world's leading stone exporters [

12]. Despite this resilience, digital procurement trends particularly BIM-driven workflows are increasing competitive pressure and elevating the importance of manufacturing efficiency [

33].

These characteristics make the POStone sector particularly relevant for investigating how technology-enabled coopetition can enhance efficiency. Its operational intensity, global competition, and demonstrated capacity for innovation provide a robust environment for empirical analysis.

The deployment of the Cockpit4.0+ system presented a timely opportunity to examine coopetition in practice [

34]. With targeted funding, this IIoT-based prototype enabled real-time connectivity among rival SMEs [

35], allowing data exchange and collaboration on non-core activities while preserving competitive autonomy.

Participant firms were recruited through direct engagement with managing directors, followed by confidentiality agreements protecting client information, operational data, human resources, materials, and competitive insights. Access was granted to analytical, accounting, and production records.

To ensure data accuracy and confidentiality, the researcher performed on-site monitoring and collected quantitative data directly from digital machinery, production systems, and internal databases. This rigorous approach supported the generation of precise, high-resolution operational data for the empirical assessment.

3.3. IIoT Integration and Coopetition Network Setup

This section describes the implementation of the IIoT system within POStone SMEs and the establishment of a technology-enabled coopetition network. The IIoT infrastructure supported real-time communication, data sharing, and resource optimization, enabling competing firms to collaborate on non-core activities while maintaining strategic independence.

Building on IoT principles, the Industrial Internet of Things introduces deeper connectivity through seamless machine-to-machine communication [

36]. This enhanced interoperability enables intelligent, responsive systems that can optimize operational processes and facilitate more efficient value creation [

37]. Empirical studies highlight how IIoT technologies, particularly in predictive maintenance and remote monitoring can reduce downtime, increase productivity [

26], and create new opportunities for value co-creation within coopetition environments [

38].

In the POStone sector, a prominent IIoT solution is Cockpit4.0, a system that connects stone manufacturers to digital marketplaces through its

fingerprint4.0 functionality, enabling precise product specification, improved customer interaction, and higher productivity [

39]. Beyond supporting individual firm performance, Cockpit4.0 enables coopetition by providing digital tools that facilitate resource sharing, predictive analytics, and collaborative service offerings [

35].

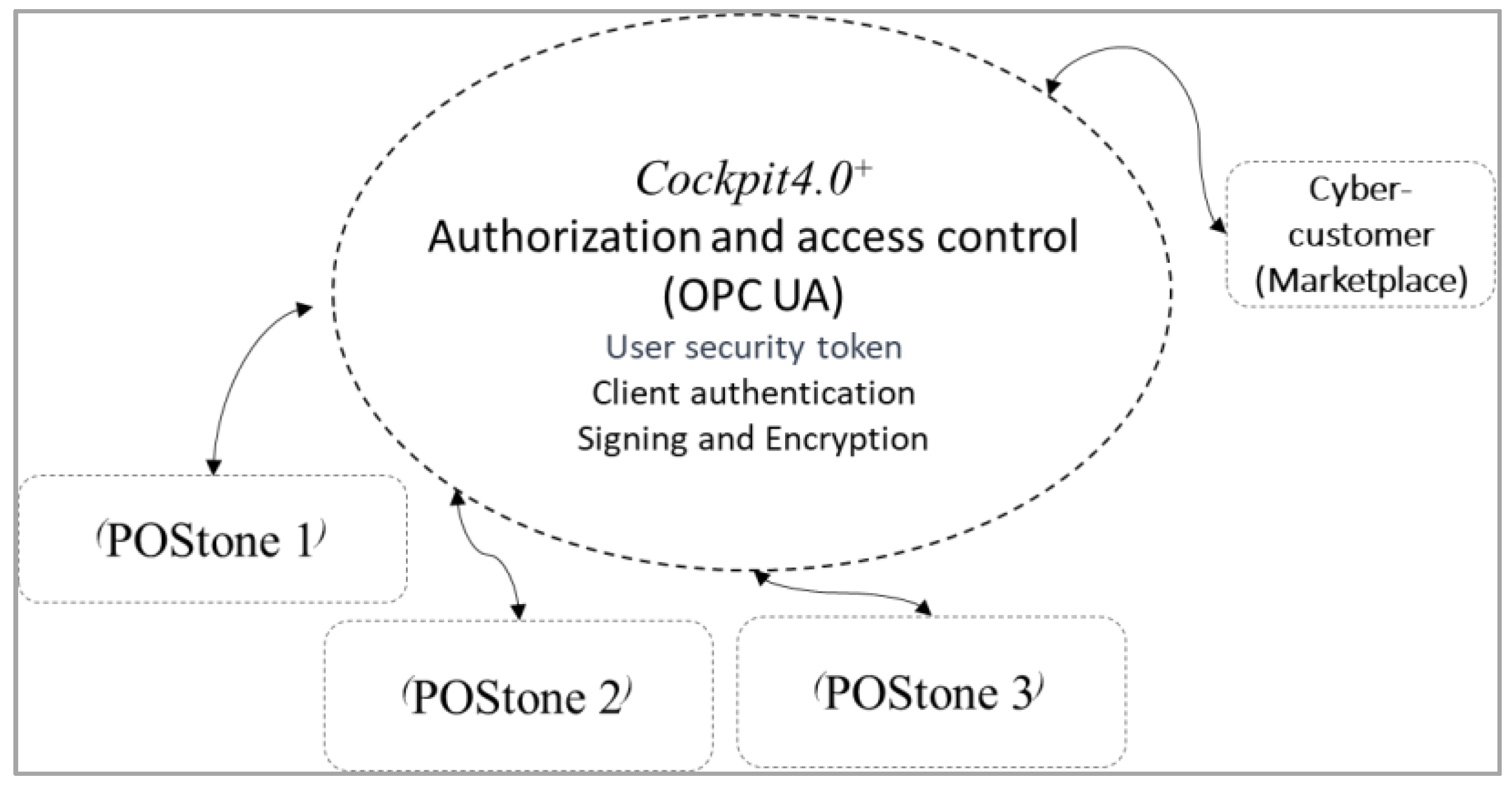

The upgraded Cockpit4.0+ platform further expands these capabilities by integrating secure OPC-UA communication and an extensive sensor network across all shop-floor machinery [

40]. This architecture connects operand technologies (hardware and software used by workers) with operant technologies (autonomous, intelligent systems), enabling coordinated manufacturing execution across multiple factories [

37]. The result is a robust technological environment that supports shared decision-making, improves responsiveness, and enhances overall productivity within the coopetition network.

Implementation of the coopetition network began with exploratory discussions with managing directors from potential participant SMEs. Formal invitations followed, accompanied by a confidentiality agreement that safeguarded operational, commercial, and competitive data. Due to the system’s prototype status, its associated costs, and potential operational disruptions, three technologically advanced SMEs agreed to participate.

Data collection proceeded in two phases. The first established a baseline for SoAP, followed by a second phase conducted after network activation, referred to as Coopetition Network Practices (CnP). During CnP, SMEs shared production resources and real-time raw material inventories to meet daily manufacturing demands.

Figure 1 illustrates the coopetition network structure used for data collection.

To ensure data accuracy and confidentiality, daily monitoring was performed using digital machinery logs and centralised database records. This rigorous approach enabled consistent, reliable collection of operational data during both SoAP and CnP phases, allowing a precise assessment of coopetition’s impact on manufacturing performance.

3.4. KPI Framework for Manufacturing Efficiency

Manufacturing efficiency in SMEs arises from the interplay of production processes, logistics, human resources, and strategic choices. To evaluate these dimensions, this study adopts a combined perspective from S-D Logic and Open Innovation.

In S-D Logic, efficiency is viewed as a

value co-creation outcome that emerges from the integration of operant resources (knowledge, skills, technology) with operand resources (materials, equipment) [

41]. Value is not embedded in outputs but cocreated through interactions, shifting the focus from value-in-exchange to value-in-use [

42].

Open Innovation complements this view by emphasizing collaboration and the incorporation of external knowledge to strengthen innovation performance, improve processes, and enhance competitiveness [

43]. Therefore, the KPIs selected in this study capture not only operational outcomes but also

value co-creation dynamics enabled by coopetition and knowledge integration. [

11]. Four KPIs widely used in industrial efficiency assessment were adopted, each representing a different determinant of manufacturing performance.

First Time Through (KPIFTT) measures the share of products meeting quality requirements on the first attempt, without rework [

44].

In S-D Logic, a higher KPIFTT reflects strong integration of operant and operand resources [

20]. Under Open Innovation, it indicates successful incorporation of external knowledge that reduced defects and improved process robustness [

40].

Performance Efficiency (KPIPE) evaluates the number of accepted parts produced per hour, capturing speed and capability.

From a co-creation perspective, higher KPIPE signals efficient coordination among ecosystem actors. In Open Innovation, it reflects the integration of technologies and practices that accelerate throughput.

Raw Material Yield (KPIRMY) measures the efficiency with which raw materials are transformed into approved outputs [

45].

A higher value indicates improved sustainability, reduced waste, and better use of material resources, key aspects of both S-D Logic (resource integration) and Open Innovation (externally enabled process improvement).

Labour Productivity (KPILP) measures the amount of accepted output produced per unit of labour [

46].

This KPI captures the value co-created through human–technology integration and indicates whether external innovations have enhanced workforce performance.

3.5. Innovation Outcomes

To assess the impact of the coopetition network on manufacturing efficiency, Innovation Outcomes (IOs) were calculated by comparing KPI values under State-of-the-Art Practices (SoAP) and Coopetition Network Practices (CnP) [

47]. These outcomes quantify both the magnitude of improvement (

IO(QTT)) and the stability or predictability of performance changes (

IO(σ)).

Table 1 summarises the formulas used for each KPI.

The consistency KPI(σ) evaluates the variability between SoAP and CnP observations, providing insight into the stability of efficiency gains:

This indicator reflects the stability and predictability of efficiency improvements. A lower KPI(σ) indicates more predictable and stable performance during CnP.

Table 1 summarizes the full formulas used to compute Innovation Outcomes for each KPI:

Collectively, these KPIs and IO formulas provide a structured, innovation-oriented framework to assess how SMEs cocreate value, enhance efficiency, and benefit from coopetition-enabled resource integration.

3.6. Data Collection and KPI Assessment

To evaluate the transition from State-of-the-Art Practices (SoAP) to Coopetition Network Practices (CnP), data were collected over two independent 54-day intervals. This design allowed for a controlled comparison of operational performance before and after the implementation of the coopetition network. In accordance with the confidentiality agreement, all data were anonymized, and the participating companies are referenced as POStone 1, POStone 2, and POStone 3.

The first data collection phase took place from April to June 2024, capturing operational behaviour under SoAP. During this stage, each SME operated independently, relying solely on its own internal resources. These data served as the baseline for assessing subsequent efficiency improvements.

The second phase, conducted from September to November 2024, recorded performance under CnP, following the activation of the IIoT-enabled coopetition network. This phase marked a shift toward shared resource use, real-time data exchange, and coordinated decision-making. The identical duration and structured observation ensured comparability between the two conditions.

Table 2 presents the aggregated daily averages for key operational variables collected in both phases.

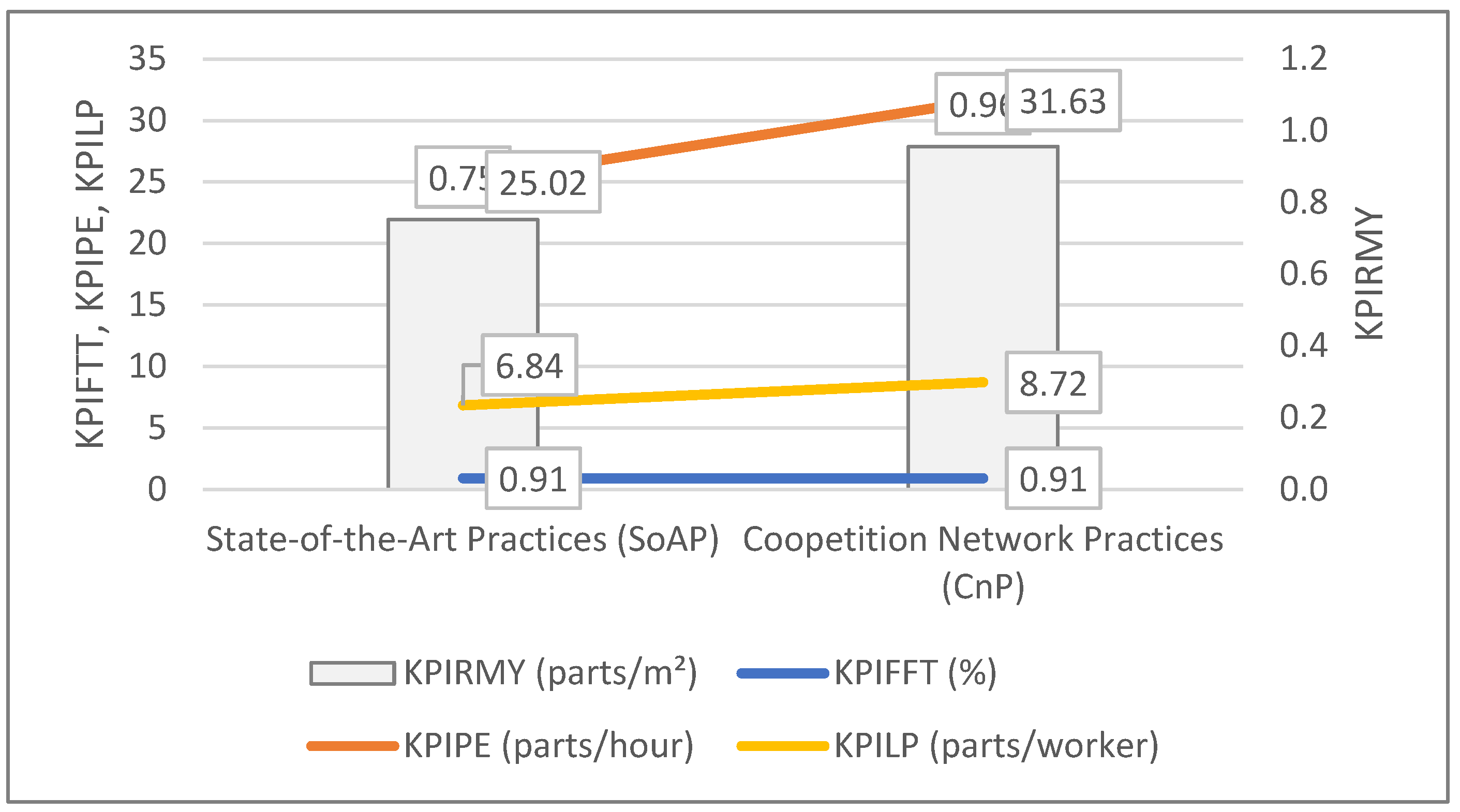

All data were exported to Excel files following standardized recording and verification procedures to ensure accuracy, security, and consistency across companies. KPI calculations followed Equations 1–5 and were used to assess changes in First Time Through, Performance Efficiency, Raw Material Yield, and Labour Productivity. Table 3 summarises the KPI values under each operational condition, along with the corresponding IO.

Table 4.

KPIs Assessment under State-of-the-Art and Coopetition Network Practices.

Table 4.

KPIs Assessment under State-of-the-Art and Coopetition Network Practices.

| KPIs |

SoAP |

CnP |

IO(QTT)

|

IO(σ) |

| KPIFTT (%) |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.0% |

0.66% |

| KPIPE (parts/hour) |

25.02 |

31.63 |

66.1% |

1.70% |

| KPIRMY (parts/m²) |

0.75 |

0.96 |

20.4% |

1.72% |

| KPILP (parts/worker) |

6.84 |

8.72 |

18.7% |

0.77% |

These findings provide the quantitative foundation for subsequent analysis of how coopetition influences the determinants of manufacturing efficiency within IIoT-enabled SME networks.

4. Results

4.1. First Time Through (KPIFTT)

The KPIFTT results provide insight into quality performance under both operational conditions. Under SoAP, SMEs produced an average of 369.9 parts per day, with 31.3 defects, yielding a KPIFTT of 90.9%. This indicates strong baseline quality control. The variability measure (KPI(σ)FTT = 0.106) reflects moderate fluctuations in first-pass success.

Under CnP, the KPIFTT remained unchanged at 90.9%, demonstrating that joining the coopetition network did not compromise quality. However, production volume increased substantially to 454.4 parts per day, indicating enhanced operational capacity. Variability increased to KPI(σ)FTT = 0.185, reflecting differing degrees of process alignment across networked firms.

Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that coopetition increases efficiency while preserving quality. The stability of KPIFTT, paired with increased throughput, is consistent with S-D Logic’s emphasis on improved value co-creation through resource integration.

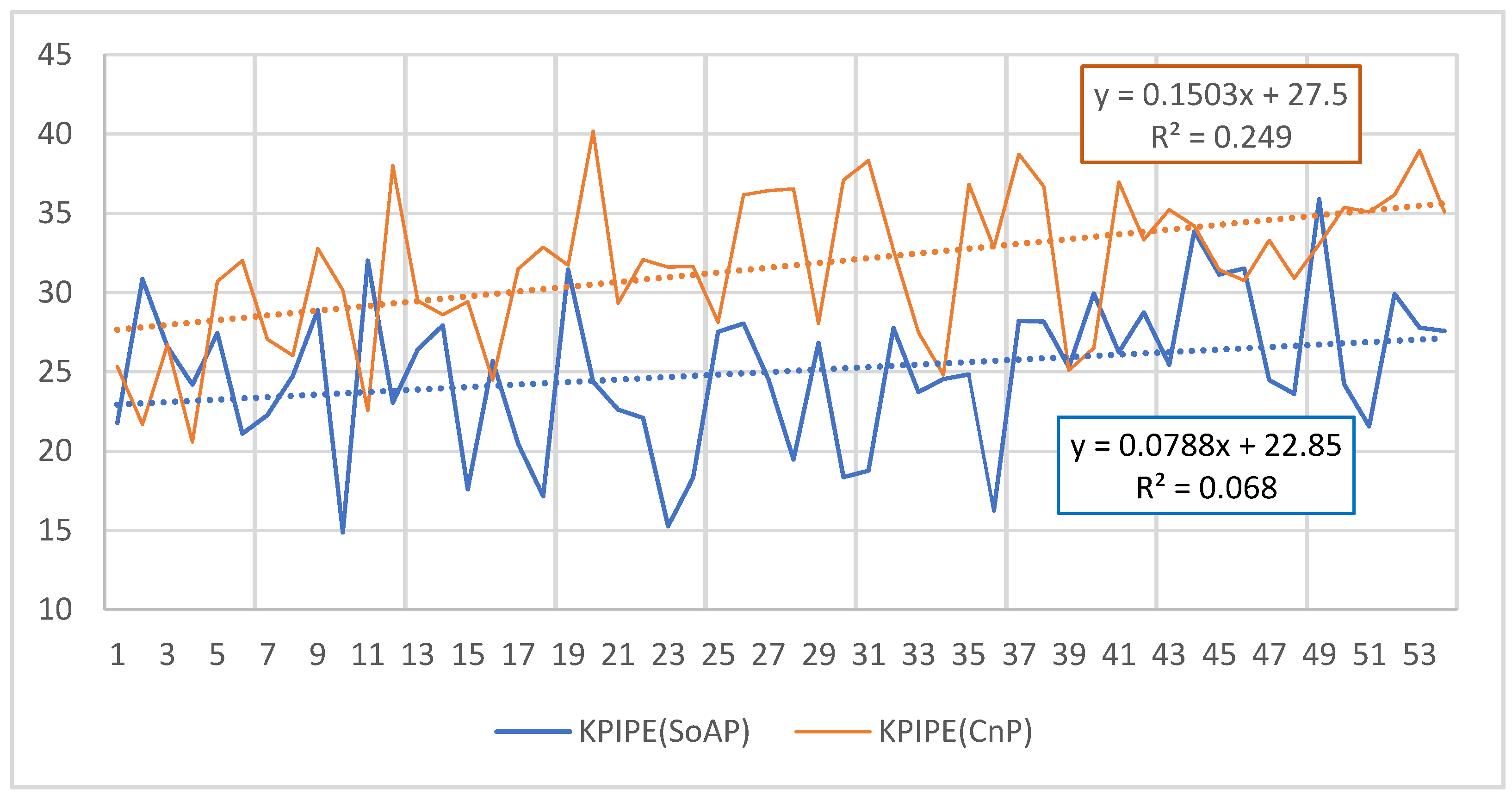

4.2. Performance Efficiency (KPIPE)

KPIPE shows marked productivity gains. Under SoAP, SMEs shipped 338.3 parts per day with 13.3 operating hours, resulting in KPIPE = 25.02 parts/hour (variability: KPI(σ)PE = 0.098).

Under CnP, output rose to 415.8 parts/day, and KPIPE increased to 31.63 parts/hour, representing a 66.1% improvement. This increase occurred without additional labour hours, demonstrating that gains came from improved coordination and resource sharing. Variability rose to KPI(σ)PE = 0.61, reflecting increased dynamism in early stages of network integration.

Figure 2 illustrates the upward trend in KPIPE values during CnP.

Although the regression model explains 24.9% of the variation (R² = 0.249), the trend reflects consistent performance improvement over time. These results validate that coopetition enhances operational throughput and flexibility.

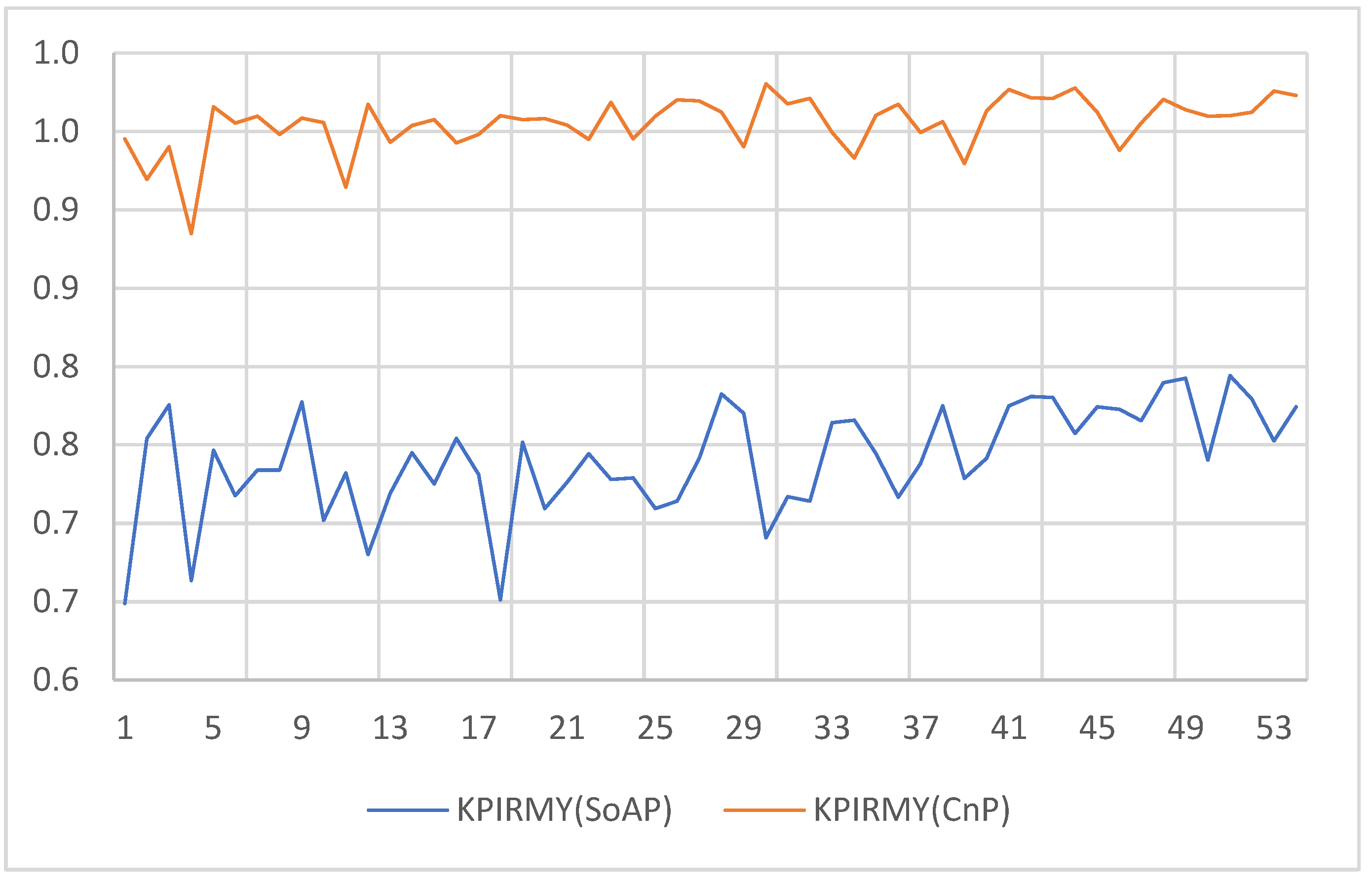

4.3. Raw Material Yield (KPIRMY)

Under SoAP, SMEs processed 425.3 m² of raw material daily and produced 323.7 accepted parts, yielding KPIRMY = 0.752 parts/m² (variability: KPI(σ)RMY = 0.005).

Under CnP, raw material use increased slightly to 437.1 m², but accepted parts surged to 454.3, producing KPIRMY = 0.956 parts/m². This demonstrates substantial gains in material efficiency. Variability decreased (KPI(σ)RMY = 0.003), indicating more consistent material use across firms within the network.

Figure 3 compares SoAP and CnP material yield.

These results confirm that coopetition significantly enhances sustainability and utilization of raw materials.

4.4. Labour Productivity (KPILP)

Under SoAP, SMEs produced 338.5 accepted parts per day with an average labour input of 49.9 worker-hours, resulting in KPILP = 6.8 parts/worker (variability: KPI(σ)LP = 0.154).

Under CnP, accepted output increased to 415.8 parts while labour remained constant, increasing KPILP to 8.7 parts/worker, an 18.7% improvement. Variability remained similar (KPI(σ)LP = 0.149), indicating steady worker performance across firms.

These results demonstrate that coopetition enhances workforce effectiveness by improving coordination and sharing operational knowledge. Labour productivity gains further reinforce the hypothesis that coopetition networks strengthen the determinants of manufacturing efficiency.

5. Discussion

This study examined whether coopetition enhances manufacturing efficiency in SMEs by fostering innovation and improving resource utilization. The hypothesis proposed that participation in a coopetition network supported by IIoT-enabled data sharing would lead to measurable improvements in key efficiency determinants. The results obtained from KPIFTT, KPIPE, KPIRMY, and KPILP strongly support this proposition (

Figure 4).

5.1. First Time Through (KPIFTT): Quality Maintained While Output Increased

The stability of KPIFTT across both phases indicates that coopetition did not compromise product quality. Despite substantial increases in daily output under CnP, the proportion of first-pass conforming parts remained unchanged. This suggests that quality standards were preserved even as operational capacity expanded. From an S-D Logic perspective, this reflects an effective integration of shared resources without diminishing the value delivered to customers. Thus, coopetition enabled firms to scale production while maintaining value-in-use.

5.2. Performance Efficiency (KPIPE): Productivity Gains Through Collaboration

KPIPE exhibited one of the most significant improvements, increasing by more than 60% under CnP. This emphasizes how coopetition enables SMEs to leverage shared technologies, data, and capabilities to enhance throughput without additional labour or operational time. These gains confirm that coopetition fosters innovation in operational processes, aligning with Open Innovation principles where external knowledge and shared digital infrastructures (via IIoT) improve internal efficiency.

5.3. Raw Material Yield (KPIRMY): Enhanced Sustainability and Waste Reduction

The marked improvement in KPIRMY under CnP demonstrates that SMEs used raw materials more efficiently when integrated into a coopetition network. The near-elimination of yield variability suggests that network-based coordination can standardize best practices across firms. This supports the idea that coopetition contributes not only to efficiency but also to sustainability, an increasingly important dimension of competitive advantage in manufacturing ecosystems.

5.4. Labour Productivity (KPILP): Greater Output With the Same Workforce

Labour productivity improved significantly in the CnP phase, despite unchanged staffing levels and working hours. This demonstrates that coopetition enhanced workflow coordination and operational decision-making, enabling workers to be more productive without additional labour costs. This finding reinforces both S-D Logic and Open Innovation perspectives, as it reflects increased value co-creation between human and technological resources shared within the network.

5.5. Overall Interpretation and Implications

Across all KPIs, coopetition consistently improved manufacturing efficiency. These outcomes validate the hypothesis and confirm that coopetition networks enable SMEs to: (1) integrate resources more effectively; (2) leverage shared knowledge, data, and technologies; (3) increase production capacity without compromising quality; (4) reduce waste and improve sustainability; and (5) enhance labour productivity through improved coordination.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that coopetition is a viable and advantageous strategy for SMEs operating in traditional, resource-intensive industries such as the Portuguese Ornamental Stone sector. By fostering innovation-oriented collaboration, coopetition helps firms overcome scale limitations and compete more effectively in global markets.

Thus, the study concludes that coopetition improves manufacturing efficiency in SMEs by fostering innovation and enabling more effective use of resources, labour, and materials. These insights provide a strong foundation for broader adoption of coopetition models and highlight the potential for IIoT-enabled networks to reshape manufacturing ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

This study examined whether coopetition networks enhance manufacturing efficiency in SMEs by fostering innovation, using Portuguese Ornamental Stone firms as an empirical context. The analysis of four key manufacturing KPIs, KPIFTT, KPIPE, KPIRMY, and KPILP demonstrated that coopetition significantly improves operational performance. Specifically, the coopetition network increased production output without compromising quality, improved performance efficiency, reduced raw material waste, and enhanced labour productivity. These results validate the research hypothesis and confirm that coopetition enables SMEs to optimize resources, innovate operational practices, and achieve greater efficiency.

Despite these positive outcomes, several limitations should be acknowledged. The study focuses on a single sector and a small sample of SMEs, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. The analysis is restricted to operational KPIs, excluding financial, customer-oriented, and market-based indicators. Additionally, this study examined short-term outcomes, leaving unanswered questions about the long-term sustainability and strategic implications of coopetition.

This research contributes to the literature on coopetition, Service-Dominant Logic, and Open Innovation by providing empirical evidence of how resource integration and value co-creation processes improve manufacturing efficiency. It also offers practical insights for SMEs in traditional industrial sectors, illustrating how coopetition can enhance competitiveness and resilience.

Future research should investigate the long-term effects of coopetition on innovation capability, business growth, and competitive positioning. Expanding the study to other industries would help assess the broader applicability of the findings. Incorporating additional indicators, such as financial performance, customer satisfaction, and environmental impact would provide a more holistic understanding of coopetition outcomes. Finally, examining how emerging digital technologies such as IIoT, AI, or cyber-physical systems further strengthen coopetition networks could yield valuable insights into digitally enabled collaboration models.

Author Contributions

In accordance with the CRediT taxonomy, the authors contributed to the study as follows: Conceptualization, A.S. and A.P..; Methodology, I.A.; Software, A.S.; Validation, A.S., A.P. and I.A.; Formal Analysis, I.A; Investigation, A.S.; Resources, A.S.; Data Curation, A.P.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, I.A.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.P.; Visualization, A.S.; Supervision, A.S.; Project Administration, A.S.; Funding Acquisition, A.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized dataset generated and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to confidentiality agreements with participating companies, raw operational data cannot be publicly shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participation and collaboration of the Portuguese Ornamental Stone SMEs that contributed operational data and supported the implementation of the IIoT prototype used in this study. The authors also thank the technical teams involved in the deployment and testing of the Cockpit4.0+ system for their support during the data collection phases.

References

- L. Di Bella, A. Katsinis, J. Lagüera-González, L. Odenthal, M. Hell, and B. Lozar, “Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023,” 2023.

- W. Briglauer and M. Grajek, “Effectiveness and efficiency of state aid for new broadband networks: evidence from OECD member states,” Econ. Innov. New Technol., pp. 1–29, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Medrano-Adán, V. Salas-Fumás, and J. Sanchez-Asin, “Organization of production and income inequality,” J. Econ. Manag. Strateg., Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Corbo, S. Kraus, B. Vlačić, M. Dabić, A. Caputo, and M. M. Pellegrini, “Coopetition and innovation: A review and research agenda,” Technovation, vol. 122, no. September 2022, p. 102624, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Grun, “Manifesto 2030 NEW DEAL,” 2024.

- B. Brende, “The Global Cooperation Barometer 2024.,” Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-global-cooperation-bar%0Aometer-2024/.

- A. Rouyre, A.-S. Fernandez, and O. Bruyaka, “Big problems require large collective actions: Managing multilateral coopetition in strategic innovation networks,” Technovation, vol. 132, p. 102968, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Manzhynski and G. Biedenbach, “The knotted paradox of coopetition for sustainability: Investigating the interplay between core paradox properties,” Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 110, pp. 31–45, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Navío-Marco, R. Ibar-Alonso, and M. Bujidos-Casado, "Interlinkages between coopetition and organizational innovation in Europe," J. Bus. Ind. Mark., vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 1665–1677, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Vargo and R. Lusch, “Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 5–23, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. An and A. Mikhaylov, “Technology-based forecasting approach for recognizing trade-off between time-to-market reduction and devising a scheduling process in open innovation management,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 100207, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Silva and A. Pata, “Value Creation in Technology Service Ecosystems - Empirical Case Study,” in Innovations in Industrial Engeneering II, 2022, pp. 26–36, doi: doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09360-9_3.

- M. Chen, C. Lv, X. Wang, L. Li, and P. Yang, “A Critical Review of Studies on Coopetition in Educational Settings,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 10, pp. 1–18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Chim-miki and R. L. C. Fernandes, “Rethinking cluster under coopetition strategy : an integrative literature review and research agenda,” pp. 2269–2307, 2025, doi: doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00434-z.

- P. Klimas, A. A. Ahmadian, M. Soltani, M. Shahbazi, and A. Hamidizadeh, “Coopetition, Where Do You Come From? Identification, Categorization, and Configuration of Theoretical Roots of Coopetition,” SAGE Open, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 215824402210850, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Bouncken, V. Fredrich, P. Ritala, and S. Kraus, “Coopetition in New Product Development Alliances: Advantages and Tensions for Incremental and Radical Innovation,” Br. J. Manag., vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 391–410, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Raza-Ullah, M. Bengtsson, and S. Kock, “The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels,” Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 189–198, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Vargo and R. F. Lusch, “Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing,” J. Mark., vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Akaka, H. Schau, and S. L. Vargo, “How Practice Diffusion Drives IoT Technology Adoption and Institutionalization of Solutions in Service Ecosystems.,” in 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS 2023, Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2023, pp. 1427–1435, [Online]. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/102808.

- M. Kleinaltenkamp, M. J. Kleinaltenkamp, and I. O. Karpen, “Resource entanglement and indeterminacy: Advancing the service-dominant logic through the philosophy of Karen Barad,” Mark. Theory, vol. Vol. 0(0), Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wieland, N. Hartmann, and S. Vargo, “Business models as service strategy,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 925–943, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. West and M. Bogers, “Open innovation: current status and research opportunities,” Innovation, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 43–50, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Sá, J. J. M. Ferreira, and S. Jayantilal, “Open innovation strategy: a systematic literature review,” Eur. J. Innov. Manag., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 454–510, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragazou, I. Passas, A. Garefalakis, and I. Dimou, “Investigating the Research Trends on Strategic Ambidexterity, Agility, and Open Innovation in SMEs: Perceptions from Bibliometric Analysis,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 118, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Dritsas and M. Trigka, “A Survey on the Applications of Cloud Computing in the Industrial Internet of Things,” 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Latif, G. Ben Brahim, S. E. Abdelhamid, R. Alghazo, G. Alhabib, and K. Alnujaidi, “Learning at Your Fingertips: An Innovative IoT-Based AI-Powered Braille Learning System,” Appl. Syst. Innov., vol. 6, no. 5, p. 91, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Islam and L. Liu, “Topology optimization of fiber-reinforced structures with discrete fiber orientations for additive manufacturing,” Comput. Struct., vol. 301, p. 107468, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Serror, S. Hack, M. Henze, M. Schuba, and K. Wehrle, “Challenges and Opportunities in Securing the Industrial Internet of Things,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 2985–2996, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Afrin et al., “Industrial Internet of Things: Implementations, challenges, and potential solutions across various industries,” Comput. Ind., vol. 170, p. 104317, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hsu, “Integrating Service Science and Information System Technology: A Case Study,” Int. J. Organ. Innov., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 158–173, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Johnson and A. J. Onwuegbuzie, “Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come,” Educ. Res., vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 14–26, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Machado et al., “Geoconservation in the Cabeço da Ladeira Paleontological Site (Serras de Aire e Candeeiros Nature Park, Portugal): Exquisite Preservation of Animals and Their Behavioral Activities in a Middle Jurassic Carbonate Tidal Flat,” Geosciences, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 366, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva and A. Cardoso, “CARBON FOOTPRINT REDUCTION ON MANUFACTURING SMES FROM DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES,” Dec. 2023, pp. 523–529. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva, A. Dionisio, and I. Almeida, “Enabling Cyber-Physical Systems for Industry 4.0 operations: A Service Science Perspective,” Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 838–846, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. da Silva and A. J. M. Cardoso, “Coopetition with the Industrial IoT: A Service-Dominant Logic Approach,” Appl. Syst. Innov., vol. 7, no. 3, p. 47, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Yazdinejad, B. Zolfaghari, A. Dehghantanha, H. Karimipour, G. Srivastava, and R. Parizi, “Accurate threat hunting in industrial internet of things edge devices,” Digital Communications and Networks, vol. 9, no. 5. pp. 1123–1130, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Hoppe, “OPC Unified Architecture-Interoperability for Industrie 4.0 and the Internet of Things,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://opcfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/OPC-UA-Interoperability-For-Industrie4-and-IoT-EN.pdf.

- A. P. Clasen, F. Agostinho, C. M. V. B. Almeida, G. Liu, and B. F. Giannetti, “Advancing towards circular economy: Environmental benefits of an innovative biorefinery for municipal solid waste management,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 46, pp. 571–581, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Silva and M. M. Gil, “Industrial processes optimization in digital marketplace context: A case study in ornamental stone sector,” Results Eng., vol. 7, p. 100152, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Fahma, W. Sutopo, E. Pujiyanto, and M. Nizam, “Dynamic open innovation to determine technology-based interoperability requirement for electric motorcycle swappable battery,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 10, no. 2, p. 100259, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. N. Hartmann, H. Wieland, and S. L. Vargo, “Converging on a New Theoretical Foundation for Selling,” J. Mark., vol. 82, no. 2, pp. 1–18, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Vargo and R. F. Lusch, “Service-dominant logic 2025,” Int. J. Res. Mark., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 46–67, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. West and M. Bogers, “Leveraging External Sources of Innovation: A Review of Research on Open Innovation,” J. Prod. Innov. Manag., vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 814–831, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Polat and S. Demirkesen, “Measuring the impact of lean implementation on BIM and project success: case of construction firms,” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag., Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Geissbauer, E. Lübben, S. Schrauf, and S. Pillsbury, Global Digital Operations Study 2018 - Digital Champions. 2018.

- E. A. Poirier, S. Staub-French, and D. Forgues, “Measuring the impact of BIM on labor productivity in a small specialty contracting enterprise through action-research,” Autom. Constr. 58 74–84, vol. 58, pp. 74–84, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Hmoud, A. S. Al-Adwan, O. Horani, H. Yaseen, and J. Z. Al Zoubi, “Factors influencing business intelligence adoption by higher education institutions,” J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 9, no. 3, p. 100111, 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).