1. Introduction

In an era characterized by market globalization and resource asymmetry, the business network landscape has undergone profound transformations, giving rise to diverse and complex network structures (Hartmann et al., 2018). One such structure, coopetition—defined as the simultaneous collaboration and competition between firms—has emerged as a crucial strategy for reshaping organizational dynamics and network ecosystems (Meena et al., 2023). Coopetition enables firms to leverage competitive advantages (Da Silva & Cardoso, 2024) while mitigating external risks and uncertainties (Garay-Rondero et al., 2020). Despite increasing academic attention to this phenomenon (Corbo et al., 2023), significant gaps remain in understanding how coopetition networks facilitate or obstruct value creation and capture (Manzhynski & Biedenbach, 2023). These gaps are particularly pressing given the transient nature of coopetition networks, which often dissolve prematurely before achieving their intended objectives (Reeves et al., 2022)

Existing research primarily examines coopetition through two dominant lenses. First, the competitive dynamics perspective explores firm behaviour and market structuring as critical drivers (Gnyawali & Ryan Charleton, 2018) (R. Bouncken et al., 2024). Second, the resource-based view positions coopetition as a strategic pathway to accessing unattainable resources, enabling firms to exploit unique capabilities for competitive advantage (Meena et al., 2023). While these perspectives provide valuable insights, they primarily focus on dyadic relationships, neglecting the broader complexities of multi-party interactions in networked environments (Xie et al., 2023).

A critical shortcoming in the literature lies in the limited exploration of value-creation mechanisms and the crucial role of technology within coopetition networks (Chen et al., 2023). Although theoretical frameworks such as game theory, the resource-based view, paradox theory, transaction cost theory, and network theory have been widely applied, there remains a lack of clarity regarding how value is created, distributed, and sustained among diverse stakeholders (Meena et al., 2023). This is particularly concerning as unmet expectations often drive the premature collapse of coopetition networks (Corbo et al., 2023). Recognizing the increasing significance of technology in modern business ecosystems, this study addresses the following research question: "What framework is best suited for coopetition networks to meet customer expectations?"

To answer this question, the research adopts Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic) as its theoretical foundation (Stephen L. Vargo et al., 2024). S-D Logic emphasizes that value is co-created through resource integration and reciprocal service exchange processes among actors in service ecosystems (Wieland et al., 2017), positioning customers as essential participants in the value creation process (Stephen L. Vargo & Lusch, 2004b). This perspective highlights the importance of partner collaboration ecosystems in coopetition networks to align firms' collective efforts to meet customer expectations (Elo et al., 2024). By leveraging advanced technologies, such as IoT-based systems, firms can optimize their resource-sharing capabilities and operational coordination (Mustak & Plé, 2020), enabling them to deliver outcomes that resonate more effectively with customer needs (Ho et al., 2020) (Jaakkola et al., 2024).

This research tests the hypothesis that transitioning to technology-driven coopetition networks enhances value co-creation by enabling firms to better align their offerings with customer expectations. By fostering collaborative processes and integrating shared resources, coopetition networks can improve perceived product quality and operational consistency, which are critical in meeting customer requirements and driving sustainable value co-creation.

To empirically test this hypothesis, the study focuses on the Portuguese ornamental stone SME sector, an industry of national significance with global reach. Through developing and implementing an experimental technology-driven coopetition network, the research examines how technological integration supports firms in aligning their production capabilities and resource utilization with evolving customer needs. This alignment ultimately improves customer-perceived product quality and enhances the value co-creation process within the network.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: The literature review explores the role of technology in enabling resource integration and value co-creation within coopetition networks. The research design outlines the methodological approach employed to address the research question and test the proposed hypothesis. The study develops and validates a framework for enhancing customer expectations through technology-driven coopetition networks by investigating the interplay between coopetition, technology, and value co-creation.

2. Literature Review

Coopetition has gained increasing recognition in recent business literature as a key strategy for enhancing competitive advantage and fostering innovation within networks (Crick & Crick, 2020). Coopetition serves dual strategic purposes: a deliberate move to strengthen market power (Dagnino & Padula, 2002) or a dynamic response to external opportunities and threats (R. B. Bouncken et al., 2018). A firm's knowledge structure often influences the decision to engage in coopetition, which shapes its strategic choices to cooperate, compete, or adopt a combination of both (Bicen et al., 2021). At the core of coopetition’s strategic value lies its orientation toward innovation, enabling firms to bridge knowledge gaps and effectively address market challenges (R. Bouncken et al., 2024).

Coopetition networks arise at the intersection of cooperative and competitive interests, where firms recognize the mutual benefits of collaboration despite direct competition in certain areas (Crick & Crick, 2020). These interactions often extend beyond dyadic relationships, evolving into multi-firm networks where participants collaborate equally to achieve common goals (Bengtsson et al., 2016).

Scholarly perspectives on coopetition are diverse. Some researchers conceptualize these relationships as hybrid networks characterized by paradoxical interactions between cooperation and competition (Meena et al., 2023). Analytical frameworks generally fall into two primary lenses: (1) Competitive dynamics, which emphasize the structural and behavioural aspects of relationships (Bengtsson et al., 2016); and (2) Resource-advantage perspective, which views coopetition as a strategic mechanism to access otherwise unattainable resources, enhancing firms’ competitive capabilities (Mwesiumo et al., 2023).

Despite the varying viewpoints, the prevailing consensus highlights the firm-centric nature of coopetition, where individual competitiveness often takes precedence over collective value creation within networks (Meena et al., 2023).

Empirical research underscores the advantages of coopetition, including access to new markets, external knowledge sharing, risk and cost distribution, and enhanced scalability through asset complementarity (Lascaux, 2020). Coopetition has been linked to increased innovation, particularly in supply chain security and knowledge creation processes (R. Bouncken et al., 2024).

Table 1 provides an overview of key definitions and perspectives on coopetition.

While coopetition delivers notable advantages, several critical research gaps persist:

RG1: The predominant focus on individual competitive benefits overshadows processes for collective value creation. How can value creation in coopetition networks be effectively addressed?

RG2: Variability in firms’ motivations leads to unresolved dysfunctions within coopetition networks. How can dysfunctions in coopetition networks be managed?

RG3: Despite coopetition's recognized complexity, discussions on coordination mechanisms for balancing collaboration and competition still need to be improved. How can coordination among actors in coopetition networks be facilitated?

Moreover, coopetition networks are prone to significant challenges, including uncertainty, competitive pressures, and risks like know-how leakage. These challenges can sometimes outweigh the benefits, leading to the premature dissolution of coopetition relationships (Crick, 2019).

2.1. Value Creation Through the Lens of Service-Dominant Logic

The conceptualization of "service" as a cornerstone of economic exchange can be traced back to the mid-19th century with early thinkers like Frederick Bastiat (1848). However, in the early 21st century, Lusch and Vargo (2004) revolutionized this discourse by introducing S-D Logic (Stephen L. Vargo & Lusch, 2004b). This paradigm shift placed operant resources—intangible assets such as knowledge, skills, and capabilities—at the forefront of value creation (R. Lusch & Nambisan, 2015), challenging the traditional operand-resource view prioritizing tangible goods. In the S-D Logic perspective (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2023), goods are not the primary creators of value but serve as vehicles for service delivery, embodying the application of specialized competencies to benefit others (Matthies et al., 2016).

At its core, S-D Logic redefines value creation as a co-creation process, emphasizing that value emerges through interactions among various actors within a networked ecosystem (R. B. Bouncken et al., 2018). This perspective aligns with foundational theories such as the resource-based view (Klimas et al., 2023), competency core theory (Autio & Thomas, 2014), and corporate core competencies theory (Antai, 2010), underscoring its broad applicability to contemporary discussions on value generation (

Table 2).

Historically, classical economists like Adam Smith (1776) and David Ricardo (1817) approached value through the lens of labour theory, focusing on tangible production. However, modern economic discourse has evolved to embrace value co-creation, which highlights the collaborative roles of suppliers, partners, and customers in generating value (Normann & Ramirez, 1993). This evolution—from coproduction to co-creation, and ultimately to value co-creation within service ecosystems—reflects an enhanced understanding of value as multifaceted and dynamic (Stephen L. Vargo & Lusch, 2014).

Under S-D Logic, service ecosystems are viewed as complex adaptive systems where value is derived and continuously re-evaluated through actor interactions. Instead of viewing value as a predefined delivery, S-D Logic emphasizes the role of value propositions as facilitators of co-creative interactions (Stephen L. Vargo et al., 2024). This perspective further distinguishes between value-in-exchange (traditional market transactions) and value-in-use (value derived through application and interaction), emphasizing the process-oriented and relational nature of value creation and realization (Stephen L. Vargo et al., 2024).

2.2. Value Networks and Technology as Catalyst for Collaborative Value Creation

Granovetter (1985) emphasizes that economic behaviours are embedded within network relationships, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of how cooperation and competition operate at multiple levels (Borgatti et al., 1990). Other historical perspectives on networks, rooted in sociology and organizational theory, highlight their structural implications for value creation (Amit & Zott, 2001). However, recent scholarship calls for a reexamination of network concepts to align theoretical insights with the practical realities of contemporary industries and management practices (Corbo et al., 2023).

Building on this foundation, Mariotti (2002) introduces the concept of a value network, describing it as an interconnected ecosystem where information, technology, and human interactions converge to generate value across nodes. Mariotti highlights the role of technology in facilitating exchanges that transcend spatial and temporal boundaries, enabling dynamic collaboration and interaction among network participants (Mariotti, 2002).

The transition toward a service-oriented perspective in business literature further reinforces the importance of value networks as frameworks for understanding value creation. Within these networks, value is not delivered unilaterally but is co-created through collaborative processes. Actors—ranging from firms to customers—integrate and exchange resources through service-based interactions, fostering mutual value creation (R. F. Lusch et al., 2010).

The concept of "network" plays a dual role in modern economic and social ecosystems, encompassing both networking and the structural configuration of interconnected systems. This duality highlights networks as platforms where diverse actors—individuals to organizations—interact and collaborate to achieve economic, social, and environmental objectives (Corbo et al., 2023). Within the framework of S-D Logic, networks are reconceptualized as interconnected systems of actors who contribute specialized competencies and engage in reciprocal value propositions (Breidbach & Maglio, 2016). This perspective shifts the focus from transactional exchanges of goods and services to collaborative interactions and relationships as the primary drivers of value creation (Stephen L. Vargo, Peters, et al., 2023).

Under this view, technology plays a transformative role in shaping and redefining value networks (Stephen L. Vargo, Wieland, et al., 2023). Traditionally viewed as a societal tool for addressing needs (Arthur, 2009), technology is now recognized within S-D Logic for its dual nature as both an operand resource (an enabling tool) and an operant resource (a source of knowledge and innovation) (S. L. Vargo & Lusch, 2017). This nuanced understanding positions technology as a critical enabler of value co-creation by fostering new resource integration, collaboration, and innovation (R. Lusch & Nambisan, 2015).

The convergence of digital transformation and technological innovation further amplifies technology's role within value networks. Wieland et al. (2017) explore this interplay, emphasizing how technological advancements drive service innovation, enabling network actors to integrate resources more efficiently and create enhanced value (Wieland et al., 2017). In modern ecosystems, technology connects actors and facilitates adaptive and dynamic relationships, supporting the emergence of new value propositions and resource exchanges.

Drawing on this critical evaluation of value creation mechanisms and the role of technology in coopetition networks, a theoretical framework can be formulated to test the hypothesis that transitioning to technology-driven coopetition networks enhances customer-perceived quality, thereby fostering value co-creation. This framework aims to uncover how technological advancements catalyze collaboration, drive innovation, and contribute to the sustainable success of coopetition networks.

3. Methodology

This research design is grounded in critical decisions regarding its theoretical foundation, which provides a framework for investigating complex phenomena across diverse fields such as medicine, computer science, engineering, management, and economics (Jaakkola, 2020). Integrative approaches, known for their ability to analyze both individual components and the system as a whole, are particularly suited for exploring the multifaceted nature of coopetition networks (Jelinek et al., 2006).

This study employs an integrative methodology to provide a comprehensive understanding of service-centric networks, shifting the focus from firm-centric views to a service-oriented lens emphasizing institutional change and collaborative value creation (Stephen L. Vargo et al., 2024). By facilitating processes such as logistics, learning, and knowledge transfer, coopetition within ecosystems drives innovation and enables firms to achieve collective and individual benefits (Bacon et al., 2020).

The concept of coopetition ecosystems incorporates multiple innovation processes facilitated by sharing resources and fostering an environment that enhances the network's collective capacity for innovation (Park et al., 2014). Scholars further argue that innovation in these networks is not merely an outcome but also a driver of dynamic reconfigurations within institutional spaces. These reconfigurations are shaped by ongoing interaction and co-creation, underscoring the importance of continuous adaptation within service ecosystems (Gnyawali & Ryan Charleton, 2018)

Building on S-D Logic, this study proposes an integrative framework to address existing gaps in the coopetition literature. The framework encompasses three interconnected components:

Framing Networks and Service Ecosystems: Understanding the foundational role of networks and their transformation into service ecosystems as platforms for value co-creation.

Framing Coopetition and Value Creation: Articulating how coopetition facilitates innovation and dynamic value creation processes within service ecosystems.

Bridging Theoretical Gaps: Leveraging this integrative perspective to address gaps in the coopetition literature, particularly in service ecosystems and institutional networks.

Building on these systemic constructs, the study implements a Technology-Driven Coopetition Network to test the hypothesis that transitioning to technology-driven coopetition networks enhances customer-perceived quality, thereby fostering value co-creation. This empirical testing involves the development and experimental application of a coopetition network within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector, focusing on resource integration, operational alignment, and service exchange to evaluate improvements in perceived product quality and value co-creation outcomes.

This integrative framework offers theoretical insights and practical pathways for rethinking coopetition by aligning the methodological approach with advancements in S-D Logic. It underscores the importance of continuous innovation and value co-creation processes within institutional networks, positioning coopetition as a transformative strategy for fostering sustainable growth and collaboration in dynamic service ecosystems.

4. An Integrative Framework for Institutional Coopetition Networks

4.1. The Evolution from Value Networks to Service Ecosystems

The concept of service ecosystems marks a crucial advancement in understanding the dynamics of value network coordination. Initially introduced by Ruokolainen and Kutvonen (2009), service ecosystems were defined as socio-technical, complex adaptive systems characterized by metamodels that govern network interactions (Ruokolainen & Kutvonen, 2009). This early work highlighted two primary pathways for the emergence of service ecosystems: spontaneous evolution, driven by common interests or market demands, and deliberate strategic planning, underpinned by governance principles to ensure operational coherence (Ruokolainen et al., 2011).

The transition from value networks to service ecosystems represented more than a shift in terminology—it reflected an evolution in theoretical focus. From traditional perspectives, enterprises within value networks collaborate to enhance the value of tangible and intangible products, with the primary goal of capturing market share through added value (Ruokolainen et al., 2011). However, this perspective underwent a transformative shift with the contributions of Vargo and Lusch (2011), who redefined value creation within the S-D Logic framework. They advocated moving from static value networks to dynamic service ecosystems, where resource integration is the central mechanism for connecting people, technology, and institutions, facilitating value co-creation through service exchange (Stephen L. Vargo & Lusch, 2011).

A critical advancement in this evolution was the recognition of the role played by institutions and institutional arrangements in enabling value co-creation within service ecosystems. Lusch and Vargo (2014) conceptualized service ecosystems as self-regulating systems composed of resource-integrating actors whose interactions are governed by shared institutional logic and mutual value-creation objectives (R. Lusch & Vargo, 2014). Based on Scott's (2001) definition, institutions within these ecosystems are seen as structured sets of rules, norms, and beliefs that enable and constrain actors' behaviours, rendering social interactions predictable and meaningful (Scott, 2001).

The role of institutional logic within service ecosystems, as explored by Koskela-Huotari and Vargo (2016), extends beyond organizational boundaries. Institutional logics operate at a supra-organizational level, coordinating actions and governance through material-symbolic languages that align actor behaviours within the ecosystem (Koskela-Huotari & Vargo, 2016)(Siltaloppi et al., 2016). This perspective underscores the network-centric nature of modern ecosystems, where value is co-created through the integration of resources, collaboration, and adherence to shared institutional logic (Siltaloppi et al., 2016).

By focusing on service ecosystems' systemic and adaptive nature, S-D Logic provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the complex interplay among actors, resources, and institutions. This dynamic interplay enables the ongoing process of value co-creation, positioning service ecosystems as both drivers of innovation and platforms for fostering collaborative value creation (Stephen L. Vargo, Wieland, et al., 2023).

4.2. Navigating Dual Dynamics: Framing Coopetition and Value Creation

In business literature, coopetition has been conceptualized as embodying two distinct yet interconnected dimensions. Bengtsson and Kock (2014) describe these dimensions as "parallel lanes," where firms collaborate with rivals in specific markets or activities while maintaining competitive postures in others (Bengtsson & Kock, 2014). This duality creates strategic opportunities and operational challenges, requiring firms to balance these opposing forces to achieve sustainable outcomes carefully (Meena et al., 2023).

Contrasting this "dual-lane" perspective, other scholars introduce the concept of syncretic rent-seeking behaviour (Álvarez Gil et al., 2005). From this viewpoint, coopetition is not a simple balance of distinct strategies but rather an integrated approach operating along a single continuum where cooperation and competition coexist in dynamic tension (Luo, 2004). This perspective emphasizes that firms must navigate the complexities and trade-offs inherent in these dual dynamics, developing strategies to harmonize collaborative and competitive intents effectively.

The inherent tensions within coopetition networks necessitate mechanisms for managing these dynamics. Scholars highlight the importance of establishing cooperative norms, rules, and institutions to guide actor interactions and mitigate conflicts (Bicen et al., 2021). This institutionalized approach aligns closely with the S-D Logic framework, which positions service ecosystems as systems of shared institutional logic that facilitate value co-creation (Vargo & Lusch, 2017). Drawing on Scott's (2001) institutional theory, institutions within service ecosystems act as higher-order structures, providing the symbols, rules, and organizing principles needed to address tensions and paradoxes inherent in coopetition networks (Stephen L. Vargo, Wieland, et al., 2023).

Within this institutional framework, value cooperation in coopetition networks emerges through dynamic service exchanges among various actors, including firms, competitors, customers, and regulatory authorities (M. Akaka & Vargo, 2015). This process is inherently experiential and iterative, as actors continuously learn and adapt. By observing and assessing what creates value—and what does not—actors adjust their behaviours and interactions to align with evolving expectations (Barile et al., 2016).

As with any ecosystem, this dynamic learning environment fosters an ongoing cycle of adaptation and innovation, ensuring the survival and growth of coopetition networks. Firms that embrace this adaptive capacity can better navigate the dual dynamics of cooperation and competition, unlocking opportunities for sustainable value creation and enhancing their collective resilience within the network (Barile et al., 2016).

4.3. Addressing Coopetition Challenges Through the Lens of Service Ecosystems

Coopetition networks provide platforms for firms to acquire and integrate resources and capabilities, enhancing their competitive advantage and innovation capacity (Rindfleisch & Moorman, 2003). This aligns with the S-D Logic perspective, which positions all actors as resource integrators and views value as co-created through dynamic service exchanges. Institutions—understood as shared rules, norms, and meanings—are crucial in enabling and constraining actions, ensuring coordinated value co-creation within complex service ecosystems (S. Vargo & Lusch, 2016). To address critical challenges within coopetition networks, this section explores how the service ecosystem perspective provides solutions to the identified research gaps (RG1, RG2, RG3):

Bridging the RG1 - Overcoming the Focus on Individual Competitive Benefits to Enable Collective Value Creation: Focusing on individual firm competitiveness often overshadows collective value creation processes. Through the lens of S-D Logic, value creation is conceptualized as a shared process where firms collaborate to integrate resources and generate mutual benefits. In coopetition networks, actors must recognize that value emerges not from isolated outcomes but from reciprocal exchanges and service integration across the ecosystem. Institutions play a critical role in facilitating this transition. By establishing shared norms, expectations, and collaborative frameworks, institutions encourage firms to shift from a firm-centric mindset to a network-centric approach. Resource integration within coopetition networks ensures that firms collectively enhance operational efficiency and deliver value propositions that align with customer expectations. This process addresses RG1 by repositioning value creation as a collective endeavour that benefits all network participants (Bacon et al., 2020).

Bridging the RG2 - Managing Variability in Motivations to Overcome Dysfunctional Coopetition: Variability in firms' motivations can lead to unresolved dysfunctions, including trust issues, competitive misalignment, and resource misuse. Addressing these challenges requires implementing institutional arrangements that establish organic governance mechanisms and align actor behaviours. Through shared norms, social rules, and evaluative frameworks, institutions serve as stabilizing forces that guide interactions within the network. By adopting a service ecosystem perspective, firms can effectively navigate tensions between collaboration and competition. Shared institutional logic provides actors with common goals and a structured approach to resolving conflicts. For example, confidentiality agreements, operational norms, and incentive mechanisms can reduce opportunism and align motivations, enabling firms to balance their competitive and cooperative intents. This structured governance ensures that coopetition relationships remain productive, addressing RG2 by reducing dysfunctions and fostering trust-driven coordination (Scott, 2013) (Bicen et al., 2021).

Bridging the RG3 - Facilitating Coordination Mechanisms to Balance Collaboration and Competition: Coopetition's inherent complexity necessitates effective coordination mechanisms to balance collaboration and competition. Institutions within service ecosystems play a dual role in facilitating coordination: they act as mechanisms for collaboration and evaluative frameworks for assessing performance. From an S-D Logic perspective, coordination emerges through actor-generated institutions, such as shared social norms, rules, and expectations, streamlining interactions and resource exchanges. Technologies, such as IoT systems and digital platforms, also function as critical enablers of coordination, allowing actors to share resources, track progress, and align operational activities dynamically. Technological solutions provide structural support for balancing the dual dynamics of coopetition by enabling firms to connect their processes and exchange services seamlessly. This systemic approach to coordination addresses RG3 by providing firms with actionable tools and institutional frameworks to facilitate collaboration without compromising competitive interests. Effective coordination ensures the sustainability of coopetition networks, enabling firms to achieve mutual gains and co-create value over time

By addressing these research gaps, the service ecosystem perspective provides a comprehensive understanding of coopetition networks. Institutions and institutional arrangements serve as foundational elements for (1) facilitating collective value creation through resource integration and shared norms, (2) managing variability in motivations by establishing governance mechanisms that align actor behaviours and reduce dysfunctions, and (3) enhancing coordination through shared frameworks, technological enablers, and evaluative mechanisms that balance collaboration and competition.

The dynamic interplay between actors, institutions, and technology underscores the importance of adaptive governance and resource alignment within coopetition networks. This perspective ensures that value is co-created sustainably while mitigating the risks of conflict, fragmentation, or co-destruction. By adopting this framework, firms can navigate the challenges of coopetition, leveraging collective capabilities to foster innovation, operational efficiency, and customer-aligned value creation.

Through the lens of S-D Logic and service ecosystems, this study demonstrates how coopetition networks can address key challenges and bridge existing gaps in value creation, actor alignment, and coordination mechanisms. By leveraging institutions and technological solutions, firms can build resilient networks that enhance value co-creation and drive sustainable growth.

5. Institutional Constructs and Systemic Building Blocks for Coopetition Networks

Understanding institutions involves recognizing their regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive dimensions in the context of coopetition networks. These institutional elements become critical when organized actors—often called institutional entrepreneurs—identify opportunities to pursue shared, highly valued interests within a network (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006). Within this institutionalized environment, cognitive institutional arrangements, as defined by Scott (2001), act as enablers for transforming coopetition networks into fertile grounds for value co-creation. This transformation aligns with the S-D Logic perspective, which envisions value co-creation as actors engaging in meaningful experiences within nested and overlapping service ecosystems. These ecosystems operate under governance and evaluation mechanisms provided by institutional arrangements.

Highlighting the critical role of dynamic interactions in networks, S-D Logic conceptualizes networks as fluid configurations of institutions (R. Lusch et al., 2016). These configurations, built upon reciprocal connections among actors, drive technological and market innovations that ensure the resilience and endurance of coopetition networks (Wieland et al., 2017).

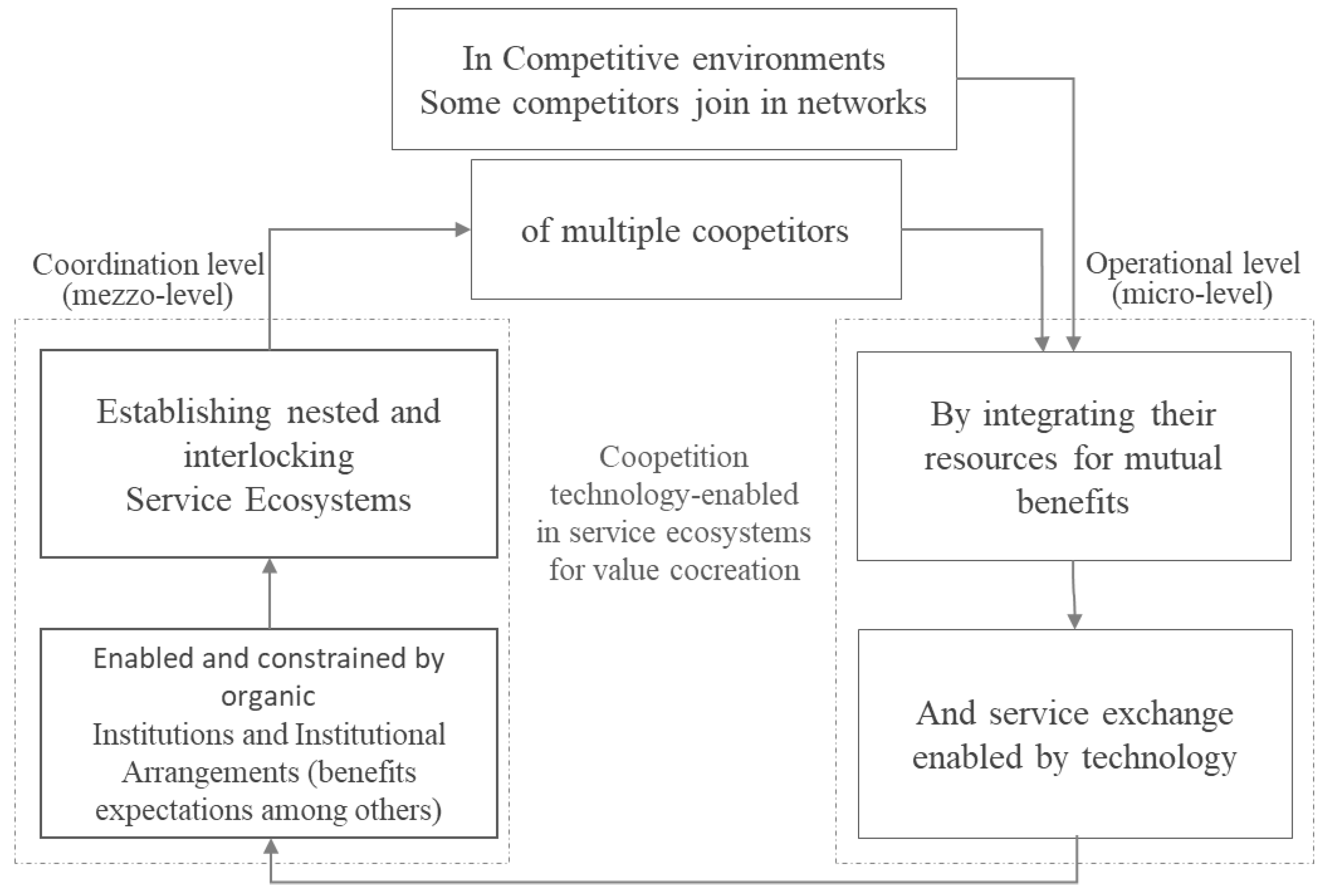

Building on the service ecosystems perspective, the following systemic constructs are proposed for understanding and developing coopetition networks:

Institutionalization: (1) emphasizes the bidirectional relationship between institutions and actor behaviours within networks, (2) institutions emerge organically through bottom-up processes, evolving from micro-level practices (actor-specific behaviours) to mezzo-level arrangements (network norms), and (3) coopetition practices at the micro-level catalyze the development of actor-generated institutions, setting the stage for future value-creation interactions within the network.

Coordination: (1) at the micro-level, firms (competitors and partners) engage in resource exchange within networks to co-create value, (2) coordination mechanisms—such as shared motivations, norms, and expectations—facilitate seamless resource integration, and (3) the outcomes of value co-creation are governed and evaluated by actor-generated institutions and broader institutional arrangements.

Technology: Technology plays a dual role within coopetition networks as both an enabler (operand resource) and an initiator (operant resource). As an institutional solution, technology reshapes resource integration patterns, enhances innovative capacity, and effectively empowers actors to co-create value.

These systemic constructs give rise to specific Systemic Building Blocks (SBBs) essential for constructing effective coopetition networks (

Figure 1). These building blocks include:

Coopetition Actors are the primary agents of value co-creation, including firms, customers, and other stakeholders. These actors navigate the dual roles of collaboration and competition within the ecosystem.

Resource Integration - the collaborative effort among actors to combine diverse resources, capabilities, and competencies to enhance the network’s collective value proposition.

Service Exchange - the mechanism through which integrated resources are offered and utilized, enabling mutual benefits and value co-creation among network participants.

Coopetition Institutions and Institutional Arrangements are the rules, norms, and cultural-cognitive elements that guide coopetition actions and governance, ensuring alignment across the network.

Nested and Overlapping Service Ecosystems - the broader context within which resource integration and service exchange occur. Multiple, interlinked layers of coopetition and collaboration characterize these ecosystems.

The role of technology as both an enabler and initiator of coopetition is captured in two additional building blocks:

Operand Technology- technologies that act as enablers of coopetition actions by providing tools and platforms for resource integration and service exchange.

Operant Technology - technologies that act as initiators of coopetition actions, driving innovation and enabling strategic reconfigurations through advanced capabilities and insights.

This study presents a comprehensive framework for understanding and developing coopetition networks within service ecosystems by identifying and integrating the systemic building blocks. The framework underscores the crucial role of institutions in shaping actor interactions, facilitating resource integration, and governing service exchanges. Furthermore, it highlights the essential function of technology as both an enabler and initiator of coopetition actions, reinforcing the dynamic and interconnected nature of modern service ecosystems.

This approach offers theoretical and practical insights into coopetition networks' structural and operational dynamics, positioning them as drivers of value co-creation, innovation, and sustainable growth within complex business ecosystems.

6. Hypothesis Testing: Implementing a Technology-Driven Coopetition Network in the Portuguese Ornamental Stone Sector

Building on the systemic building blocks, this section applies the proposed framework to an experimental technology-driven coopetition network within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector. The systemic building blocks—coopetition actors, resource integration, service exchange, institutional arrangements, nested service ecosystems, and operand and operant technologies—are the foundational elements guiding the experimental design and implementation.

The experimental network brings together a group of technologically advanced SMEs, identified as key coopetition actors, to collaboratively address the challenges of resource heterogeneity and production variability inherent to the ornamental stone sector. Participating firms leverage their collective expertise and production capabilities to meet customer expectations more effectively through strategic resource integration and coordinated service exchanges facilitated by IoT-based software systems (as operand technology). Simultaneously, the integration of operant technology drives process innovation and operational reconfigurations, enabling firms to respond dynamically to emerging demands within the network.

Institutional arrangements, including confidentiality agreements and shared operational norms, are critical in governing the coopetition network, ensuring trust, alignment, and consistency across participating actors. By situating the experimental implementation within nested service ecosystems, the study evaluates how coopetition practices optimize the exchange of resources and services across interconnected layers of collaboration and competition.

The following section details the proposed framework's empirical implementation and hypothesis testing. It examines how transitioning to a technology-driven coopetition network influences customer-perceived quality (KPIQpP), providing empirical evidence of the framework’s capacity to enhance value co-creation and operational outcomes.

6.1. Contextual Background and Experimental Design

The Portuguese ornamental stone sector holds significant historical, cultural, and economic importance. Since the 15th century, this sector has contributed to iconic monuments worldwide, showcasing Portugal’s deep-rooted expertise in stone craftsmanship. According to the Portuguese Stone Federation, the sector ranks ninth globally in the International Stone Trade and second in international trade per capita, exporting to 116 countries. Predominantly composed of SMEs, the sector has achieved remarkable economic performance: Exports exceed imports by 660%, with a substantial share reaching markets outside Europe, and in 2021 alone, the sector generated a turnover of €1.23 billion, supporting over 16,600 direct jobs, particularly in inland regions.

To test the hypothesis, a sample of stone SMEs was selected based on their technological capabilities and alignment with state-of-the-art practices within the industry. Invitations were sent to twenty-three companies identified as technological leaders in the sector. However, only six companies agreed to participate in the experimental network due to concerns regarding costs and potential operational disruptions.

The participating companies showcased advanced technological capabilities by integrating their machinery with Building Information Modeling (BIM) systems used by architects. This strategic integration enabled the seamless sharing of information and resources among firms, facilitating a collaborative evaluation of how technology-driven coopetition can enhance value co-creation.

A comprehensive confidentiality agreement was established to address concerns regarding proprietary information. This agreement safeguarded sensitive data related to operations, customers, employees, resources, and competitive positioning.

By ensuring confidentiality, all participating companies could collaborate within the coopetition framework without jeopardizing their competitive advantage or exposing proprietary knowledge.

6.1. Evaluation Metrics for Assessing Value Co-Creation

From the perspective of S-D Logic, value emerges as the result of a co-creative process in which the customer is a fundamental actor. Building on this perspective, it can be reasonably assumed that the higher the level of customer expectations meeting, the greater the co-created value. Among the various indicators suggested in the marketing literature to assess customer expectation meeting, perceived product quality is considered one of the most reliable and widely adopted Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) (Imschloss & Schwemmle, 2023).

In the context of stone SMEs supplying finished stone products, customer orders often involve multiple products, such as kitchen countertops, facades, flooring, staircases, thresholds, and baseboards. However, as stone is a natural product, its raw material is inherently heterogeneous, even within the same material type, such as granite, limestone, marble, or slate.

When a company secures an order, it must produce multiple product types using various raw materials, often needing more production capabilities or technical know-how to handle all aspects of the order efficiently. By participating in a technology-driven coopetition network, companies can distribute portions of their orders to other network members who have the necessary expertise and production capacity. Importantly, this occurs without revealing the final customer's identity, ensuring confidentiality. As a result, companies operating in a coopetition mode are better positioned to meet or exceed customer expectations, thereby improving perceived product quality.

The KPI for Perceived Product Quality (KPIQpP) evaluates the extent to which the delivered product aligns with—or exceeds—the customer’s initial expectations. This is measured using a Likert scale (1 to 5): 1 indicates that the product quality is far below expectations, and a score of 5 indicates that the product quality is well above expectations.

To assess the impact of transitioning from conventional practices to a technology-driven coopetition network, the Equation (1) is used to assess the variation in value co-creation:

Where: (1) KPIQpP(BP) - the average rating received from customers when companies operate under Best Practices (conventional methods), and (2) KPIQpP(CP) - the average rating received from customers when companies operate within the Coopetition Network.

Employing this systematic approach, the experiment provides a robust metric for understanding how cooperation networks, driven by technology integration, enhance the quality perceived by customers within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector.

6.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The data collection process was conducted over two consecutive 60-day intervals to measure the impact of transitioning from conventional best practices (CBP) to technology-driven coopetition network practices (CNP). This approach enabled a precise, comparative analysis of KPIQpP under both operational scenarios.

Phase 1: Baseline Data Collection (CBP)—The first 60-day period, conducted from April to June 2024, established a baseline measurement of customer feedback under current best practices (CBP) at the participating companies. Customers provided ratings based on their perceived product quality during this phase, using a 1-5 Likert scale. This phase served as a critical reference point for assessing the subsequent effects of coopetition.

Phase 2: Experimental Coopetition Network Practices (CNP)—The second 60-day period, conducted from September to November 2024, evaluated the effects of integrating the six participating firms into a technology-driven coopetition network. The companies were strategically connected using an IoT-based software system to facilitate seamless communication, resource sharing, and coordination (

Figure 2).

Data privacy and confidentiality agreements were strictly enforced throughout the study to safeguard sensitive information. All customer feedback and company-specific data were anonymized and referred to by company labels. This ensured a secure, consistent, and ethical approach to data management while enabling a robust and transparent analysis.

Table 3 summarises the average feedback ratings and the standard deviation of KPIQpP during both periods.

The data revealed the following key findings: (1) the average perceived product quality increased from 3.01 (under CBP) to 3.41 (under CNP), representing a 15.3% improvement; (2) the standard deviation decreased from 0.57 to 0.43, indicating a positive gain in consistency across customer feedback, (3) the number of feedback responses increased from 351 to 393, suggesting greater engagement during the coopetition phase.

The comparative analysis between CBP and CNP demonstrates that integrating a technology-driven coopetition network positively impacts perceived product quality and reduces variability. The observed 15.3% increase in average ratings, accompanied by a 24.6% reduction in standard deviation, highlights the effectiveness of coopetition networks in enhancing value co-creation within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector.

These findings support the hypothesis that transitioning to a technology-driven coopetition network can significantly improve the quality perceived by customers, consistency, and overall value co-creation outcomes.

6.3. Results and Discussion

The experiment's results provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that transitioning to a technology-driven coopetition network enhances the KPIQpP, thereby facilitating value co-creation.

Figure 3 illustrates the daily average customer rating feedback (on a 1–5 scale) during the coopetition network practices (CNP).

The positive slope of the trend line (0.0063) indicates a consistent upward trajectory in perceived product quality under coopetition practices. Although the immediate quantitative improvement may appear marginal, the sustained upward trend highlights the potential for long-term operational and quality gains.

An econometric analysis of the trend line further reveals a moderate R² value (0.0645), indicating that while time contributes to improving KPIQpP, additional factors—such as resource sharing, technological integration, and operational coordination—may influence this performance metric.

The increase in customer responses during the CNP phase suggests that participating companies handled higher order volumes, likely indicating an increase in production scale. Importantly, this increased production was not accompanied by a proportional rise in defects, underscoring the collective benefits of coopetition, including improved resource utilization, shared expertise, and operational efficiency.

A paired t-test was conducted to compare the means of KPIQpP under conventional best practices (CBP) and coopetition network practices (CNP) to validate the hypothesis statistically.

The paired t-test results reveal the following: (1) the mean KPIQpP increased from 3.0067 (CBP) to 3.4092 (CNP), (2) the calculated t-statistic is -4.5099, which exceeds the critical value of 2.0010 for a two-tailed test at a 95% confidence level, and (3) the p-value (two-tail) is 3.14 x 10-05, which is significantly lower than the 0.05 threshold.

These results provide strong statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in perceived quality. Therefore, the hypothesis is validated:

The findings demonstrate that adopting coopetition practices through technological integration positively impacts enhance quality perceived by customers and operational consistency. Key insights include: (1) the increase in mean KPIQpP by 13.4% indicates an overall improvement in perceived product quality, (2) the reduction in variance (from 0.3309 to 0.1894) highlights greater consistency in quality outcomes, suggesting improved coordination and resource integration within the network, and (3) the positive trend line slope further supports the argument that coopetition networks enable incremental quality improvements over time.

These results underscore the value of technology-driven coopetition as a mechanism for achieving operational synergies, leveraging shared resources, and enhancing collective capabilities. By enabling firms to distribute tasks based on expertise and capacity, coopetition networks allow companies to meet or exceed customer expectations more effectively, leading to increased quality perceived and sustained value co-creation.

The statistical validation through the paired t-test and trend analysis provides compelling evidence that transitioning to a technology-driven coopetition network enhances customer-perceived product quality. This improvement demonstrates the potential of coopetition practices to drive value co-creation within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study sought to answer the research question: "What framework is best suited for coopetition networks to meet customer expectations?" By adopting an S-D Logic perspective, the research proposed a technology-driven coopetition framework that integrates firms, resources, and technology within interconnected networks. The hypothesis—transitioning to technology-driven coopetition networks enhances customer-perceived quality, thereby fostering value co-creation—was tested empirically within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector.

The findings validate that coopetition networks facilitated through technological integration significantly enhance customer-perceived quality. Specifically, the KPI for KPIQpP showed a measurable improvement, increasing from an average score of 3.01 under CBP to 3.41 under CNP, representing a 13.4% increase. This improvement was accompanied by a reduction in variability, as evidenced by a decrease in the standard deviation from 0.57 to 0.43. These results confirm that coopetition enables firms to leverage collective resources, distribute tasks more effectively, and consistently meet customer expectations. The positive trend observed throughout the experimental period further highlights the potential for long-term quality improvements when firms transition to coopetition frameworks facilitated by technologies such as IoT-based systems.

The results demonstrate that the proposed framework—anchored in the S-D Logic perspective—creates fertile ground for value co-creation by aligning firms’ collaborative efforts with customer expectations. By enabling seamless resource integration and enhancing operational efficiency, technology-driven coopetition networks optimize firms’ capabilities to deliver higher-quality products, fostering sustainable value co-creation processes.

While the findings provide valuable insights, the study has limitations. First, the experimental implementation involved only six firms within the Portuguese ornamental stone sector, limiting the broader generalizability of the results. Second, the data collection occurred over two consecutive 60-day intervals, which, while sufficient for observing short-term impacts, may only partially capture the long-term dynamics and sustainability of coopetition networks. Additionally, as the study was sector-specific, further research is needed to validate the framework's applicability in other industries and markets with distinct technological readiness and operational challenges. External factors, such as market conditions or natural resource variability, may also influence customer perceptions, requiring future studies to control for such variables.

Future research should focus on expanding the scope of the study by applying the proposed framework across multiple industries and regions to enhance its generalizability. Longitudinal studies examining the long-term impacts of technology-driven coopetition networks on value co-creation will provide deeper insights into their sustainability. Furthermore, exploring the role of emerging technologies—such as artificial intelligence and blockchain—in coopetition networks can uncover additional opportunities for resource integration and enhance customer-perceived quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Agostinho da Silva and António Cardoso; methodology, Agostinho da Silva; software, Agostinho da Silva; validation, Agostinho da Silva and António Cardoso; formal analysis, Agostinho da Silva; investigation, Agostinho da Silva; resources, Agostinho da Silva; data curation, Agostinho da Silva; writing—original draft preparation, Agostinho da Silva; writing—review and editing, Agostinho da Silva; visualization, Agostinho da Silva; supervision, António Cardoso; project administration, Agostinho da Silva; funding acquisition, Agostinho da Silva. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Akaka, M., & Vargo, S. (2015). Extending the context of service: from encounters to ecosystems. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6–7), 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Akaka, Melissa, Vargo, S., & Schau, H. (2015). The context of experience. Journal of Service Management Vol. 26 No. 2, 2015 Pp. 206-223, 26(2), 206–223. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Gil, M., Berrone, P., Husillos, J., & Lado, N. (2005). The Explanatory Power of Trust And Commitment and Stakeholders’ Salience: Their Influence on The Reverse Logistics Programs Performance.

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in E-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 493–520. [CrossRef]

- Antai, I. (2010). A theory of the competing supply chain: Alternatives for development. International Business Research, 4(1), 74–85. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W. B. (2009). THE NATURE of TECHNOLOGY (S. A. Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196 (ed.)). Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4210376/mod_resource/content/1/Brian Arthur-The nature of technology-2009.pdf.

- Autio, E., & Thomas, L. D. W. (2014). Innovation Ecosystems: Implications for Innovation Management. In Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Bacon, E., Williams, M. D., & Davies, G. (2020). Coopetition in innovation ecosystems: A comparative analysis of knowledge transfer configurations. Journal of Business Research, 115(November), 307–316. [CrossRef]

- Barile, S., Lusch, R., Reynoso, J., Marialuisa, S., & Spohrer, J. (2016). Systems, Networks, and Ecosystems in Service Research. Journal of Service Management, 34(1), 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2000). ”Coopetition” in Business Networks—to Cooperate and Compete Simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition-Quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M., Kock, S., Lundgren-Henriksson, E.-L., & Näsholm, M. H. (2016). Coopetition research in theory and practice: Growing new theoretical, empirical, and methodological domains. Industrial Marketing Management, 57, 4–11. [CrossRef]

- Bicen, P., Hunt, S., & Madhavaram, S. (2021). Coopetitive innovation alliance performance: Alliance competence, alliance’s market orientation, and relational governance. Journal of Business Research, 123(October 2020), 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., Labianca, G., & Granovetter, M. (1990). The Myth of Social Network Analysis as a Special Metyhod on the Social Sciences. Science, 323(April), 892–896.

- Bouncken, R. B., Fredrich, V., Ritala, P., & Kraus, S. (2018). Coopetition in New Product Development Alliances: Advantages and Tensions for Incremental and Radical Innovation. British Journal of Management, 29(3), 391–410. [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R., Kumar, A., Connell, J., Bhattacharyya, A., & He, K. (2024). Coopetition for corporate responsibility and sustainability: does it influence firm performance? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(1), 128–154. [CrossRef]

- Breidbach, C., & Maglio, P. (2016). Technology-enabled value co-creation: An empirical analysis of actors, resources, and practices. Industrial Marketing Management, 56, 73–85. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Lv, C., Wang, X., Li, L., & Yang, P. (2023). A Critical Review of Studies on Coopetition in Educational Settings. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(10), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Corbo, L., Kraus, S., Vlačić, B., Dabić, M., Caputo, A., & Pellegrini, M. M. (2023). Coopetition and innovation: A review and research agenda. Technovation, 122(September 2022), 102624. [CrossRef]

- Crick, J. (2019). The dark side of coopetition: when collaborating with competitors is harmful for company performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 35(2), 318–337. [CrossRef]

- Crick, J., & Crick, D. (2020). Coopetition and COVID-19: Collaborative business-to-business marketing strategies in a pandemic crisis. Industrial Marketing Management, 88(May), 206–213. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A., & Cardoso, A. J. M. (2024). Coopetition Networks for SMEs: A Lifecycle Model Grounded in Service-Dominant Logic. [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, G., & Padula, G. (2002). Coopetition Strategy. Towards a New Kind of Interfirm Dynamics?”. EURAM – The European Academy of Management Second Annual Conference - “Innovative Research in Management,” May 2002, 9–11.

- Elo, J., Lumivalo, J., Tuunanen, T., & Vargo, S. L. (2024). Enabling Value Co-Creation in Partner Collaboration Ecosystems: An Institutional Work Perspective. Proceedings of the 57th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, March. https://www.sdlogic.net/pdf/post2018/24_0031.pdf.

- Eriksson, P. E. (2008). Achieving Suitable Coopetition in Buyer–Supplier Relationships: The Case of AstraZeneca. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 15(4), 425–454. [CrossRef]

- Ganz, Satzeger, & Schultz. (2012). Methods in Service Innovation: Current trends and future perspectives (F. Verlag (ed.)). Fraunhofer. https://www.ksri.kit.edu/downloads/Ganz_Satzger_Schultz_2012_Methods_in_Service_Innovation.pdf.

- Garay-Rondero, C. L., Martinez-Flores, J. L., Smith, N. R., Caballero Morales, S. O., & Aldrette-Malacara, A. (2020). Digital supply chain model in Industry 4.0. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 31(5), 887–933. [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D. R., & Ryan Charleton, T. (2018). Nuances in the Interplay of Competition and Cooperation: Towards a Theory of Coopetition. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2511–2534. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N. N., Wieland, H., & Vargo, S. L. (2018). Converging on a New Theoretical Foundation for Selling. Journal of Marketing, 82(2), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Ho, M. H. W., Chung, H. F. L., Kingshott, R., & Chiu, C. C. (2020). Customer engagement, consumption and firm performance in a multi-actor service eco-system: The moderating role of resource integration. Journal of Business Research, February, 0–1. [CrossRef]

- Imschloss, M., & Schwemmle, M. (2023). Value creation in post-pandemic retailing: a conceptual framework and implications. Journal of Business Economics. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Review, 10(1–2), 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E., Kaartemo, V., Siltaloppi, J., & Vargo, S. L. (2024). Advancing service-dominant logic with systems thinking. Journal of Business Research, 177, 114592. [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, H. F., Jones, C. L., Warfel, M. D., Lucas, C., Depardieu, C., & Aurel, G. (2006). Understanding Fractal Analysis? The Case of Fractal Linguistics. Complexus, 3(1–3), 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Kleinaltenkamp, M., Kleinaltenkamp, M. J., & Karpen, I. O. (2023). Resource entanglement and indeterminacy: Advancing the service-dominant logic through the philosophy of Karen Barad. Marketing Theory, Vol. 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Klimas, P., Ahmadian, A. A., Soltani, M., Shahbazi, M., & Hamidizadeh, A. (2023). Coopetition, Where Do You Come From? Identification, Categorization, and Configuration of Theoretical Roots of Coopetition. SAGE Open, 13(1), 215824402210850. [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K., & Vargo, S. L. (2016). Institutions as resource context. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(2), 163–178. [CrossRef]

- Lascaux, A. (2020). Coopetition and trust: What we know, where to go next. Industrial Marketing Management, 84(May), 2–18. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and Institutional Work. The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies: Chapter 6. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. (2004). A coopetition perspective of MNC–host government relations. Journal of International Management, 10(4), 431–451. [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & Tanniru, M. (2010). Service, value networks and learning. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(1), 19–31. [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R., & Nambisan, S. (2015). Service Innovation: A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 155–175. [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R., & Vargo, S. (2014). Service Ecosystems. In Service-Dominant Logic (pp. 158–176). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R., Vargo, S., & Gustafsson, A. (2016). Fostering a trans-disciplinary perspectives of service ecosystems. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2957–2963. [CrossRef]

- Manzhynski, S., & Biedenbach, G. (2023). The knotted paradox of coopetition for sustainability: Investigating the interplay between core paradox properties. Industrial Marketing Management, 110, 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, J. (2002). The value network. Executive.

- Matthies, B. D., D’Amato, D., Berghäll, S., Ekholm, T., Hoen, H. F., Holopainen, J., Korhonen, J. E., Lähtinen, K., Mattila, O., Toppinen, A., Valsta, L., Wang, L., & Yousefpour, R. (2016). An ecosystem service-dominant logic? – integrating the ecosystem service approach and the service-dominant logic. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124, 51–64. [CrossRef]

- Meena, A., Dhir, S., & Sushil, S. (2023). A review of coopetition and future research agenda. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 38(1), 118–136. [CrossRef]

- Mustak, M., & Plé, L. (2020). A critical analysis of service ecosystems research: rethinking its premises to move forward. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(3), 399–413. [CrossRef]

- Mwesiumo, D., Harun, M., & Hogset, H. (2023). Unravelling the black box between coopetition and firms’ sustainability performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 114, 110–124. [CrossRef]

- Normann, R., & Ramirez, R. (1993). From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. In Harvard Business Review (Vol. 71, Issue 4, pp. 65–77). http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9309166477&site=eds-live.

- Novak, T. P. (2017). Consumer and Object Experience in the Internet of Things : An Assemblage Theory Approach. Forthcoming, Journal of Consumer Research, 1–87.

- Park, B. J. R., Srivastava, M. K., & Gnyawali, D. R. (2014). Walking the tight rope of coopetition: Impact of competition and cooperation intensities and balance on firm innovation performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 210–221. [CrossRef]

- Raza-Ullah, T., Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). The coopetition paradox and tension in coopetition at multiple levels. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(2), 189–198. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M., Lotan, H., Legrand, J., & Jacobides, M. G. (2022). Chapter 3 How Business Ecosystems Rise (and Often Fall). In Business Ecosystems (Issue July, pp. 27–34). De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A., & Moorman, C. (2003). Interfirm Cooperation and Customer Orientation. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(4), 421–436. [CrossRef]

- Rungtusanatham, M., Salvador, F., Forza, C., & Choi, T. Y. (2003). Supply-chain linkages and operational performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23(9), 1084–1099. [CrossRef]

- Ruokolainen, T., & Kutvonen, L. (2009). Managing interoperability knowledge in open service ecosystems. 2009 13th Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference Workshops, 203–211. [CrossRef]

- Ruokolainen, T., Ruohomaa, S., & Kutvonen, L. (2011). Solving service ecosystem governance. Proceedings - IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop, EDOC, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Rusko, R. (2011). Exploring the concept of coopetition: A typology for the strategic moves of the Finnish forest industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 311–320. [CrossRef]

- Sott, W. (2001). Institutions and Organizations. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Scott, W. (2013). Institutions and Organizations - Ideas, Interests, and Identities. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Siltaloppi, J., Koskela-Huotari, K., & Vargo, S. (2016). Institutional complexity as a driver for innovation in service ecosystems. Service Science, 8(3), 333–343. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S., Akaka, M., & Vaughan, C. (2017). Conceptualizing Value: A Service-ecosystem View. Journal of Creating Value, 3(2), 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46–67. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2016). Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., Fehrer, J. A., Wieland, H., & Nariswari, A. (2024). The nature and fundamental elements of digital service innovation. Journal of Service Management, 35(2), 227–252. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004a). The Four Service Marketing Myths: Remnants of a Goods-Based, Manufacturing Model. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 324–335. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004b). Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., & Lusch, R. F. (2011). It’s all B2B…and beyond: Toward a systems perspective of the market. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., & Lusch, R. F. (2014). Inversions of service-dominant logic. Marketing Theory, 14(3), 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., Peters, L., Kjellberg, H., Koskela-Huotari, K., Nenonen, S., Polese, F., Sarno, D., & Vaughan, C. (2023). Emergence in marketing: an institutional and ecosystem framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51(1), 2–22. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, Stephen L., Wieland, H., & O’Brien, M. (2023). Service-dominant logic as a unifying theoretical framework for the re-institutionalization of the marketing discipline. Journal of Business Research, 164, 113965. [CrossRef]

- Walley, K. (2007). Coopetition: An Introduction to the Subject and an Agenda for Research. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 11–31. [CrossRef]

- Wieland, H., Hartmann, N., & Vargo, S. (2017). Business models as service strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6), 925–943. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., Gao, Y., Xia, N., Zhang, S., & Tao, G. (2023). Coopetition and organizational performance outcomes: A meta-analysis of the main and moderator effects. Journal of Business Research, 154(October 2022), 113363. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).