1. Introduction

Vitamin D is a pleiotropic hormone with established roles in mineral homeostasis and increasingly recognized functions in immune modulation, cellular proliferation control, and cancer biology [

1,

2,

3]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary liver malignancy, predominantly arises in cirrhotic livers subject to chronic inflammation and hepatic dysfunction—conditions that profoundly perturb vitamin D metabolism and transport [

4,

5,

6].

The liver is essential for two critical steps in vitamin D homeostasis: first, the 25-hydroxylation of vitamin D to generate the major circulating metabolite, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D); second, the synthesis of vitamin D-binding protein (VDBP) and albumin, which carry vitamin D in serum [

7,

8,

9]. In HCC and advanced cirrhosis, both processes are compromised by reduced hepatic synthetic capacity and systemic inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which suppress VDBP production [

10,

11,

12].

Despite evidence suggesting that low total 25(OH)D portends a worse HCC prognosis, few studies have systematically profiled the spectrum of vitamin D metabolites—including free and bioavailable fractions—in relation to clinical stage, hepatic function, and inflammation in HCC [

13,

14]. This gap has direct therapeutic implications, as vitamin D supplementation regimens tailored to total 25(OH)D may be insufficient or potentially unsafe in the context of significant protein-binding alterations [

15].

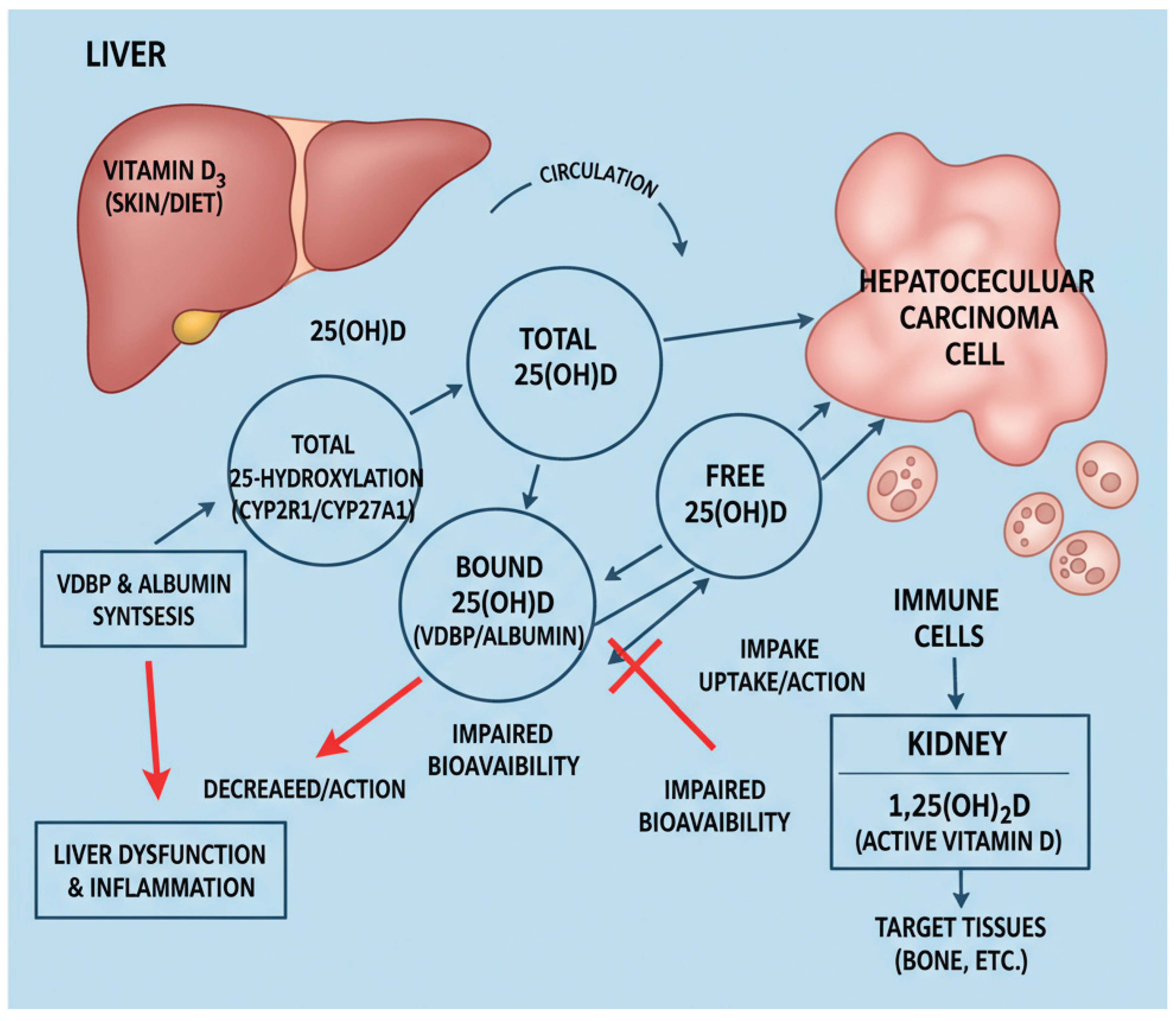

Vitamin D metabolism and bioavailability are profoundly influenced by liver function, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The liver not only converts vitamin D into its circulating form, 25(OH)D, but also synthesizes the principal VDBP and albumin, which regulate the free and bioavailable fractions accessible to target tissues. In HCC, hepatic dysfunction and systemic inflammation disrupt these pathways, leading to a decrease in the production of VDBP and albumin, thereby diminishing vitamin D bioavailability despite serum levels that may not fully reveal the deficiency [

13,

16,

17]. This complex interplay is summarized schematically in

Figure 1.

Conventionally, vitamin D status is assessed by measuring total serum 25(OH)D. However, the "free hormone hypothesis" posits that only the unbound or bioavailable fractions of hormones can cross cell membranes and activate receptors [

18,

19]. In populations with low albumin and VDBP—such as patients with HCC total 25(OH)D may substantially underestimate true vitamin D deficiency [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Recent epidemiological and translational studies support the role of vitamin D in HCC prevention and possibly prognosis, yet few investigations have comprehensively characterized all vitamin D fractions or their carrier proteins in relation to clinical liver function markers [

5,

24,

25].

The aim of this study was to systematically profile total, free, and bioavailable 25(OH)D alongside VDBP and albumin in HCC patients compared to healthy controls across seasons, and to evaluate their correlations with measures of hepatic reserve (Child-Pugh score), tumour burden (BCLC stage), and disease aetiology. We hypothesized that free and bioavailable 25(OH)D, rather than total measurements alone, would better reflect functional vitamin D deficiency and correlate with clinical disease severity in HCC.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

The HCC cohort (n = 46) consisted predominantly of male patients (39 males and 7 females) with a mean age of 71.4 ± 7.5 years, significantly older than the healthy control group (14 males and 73 females, age 35.9 ± 12.5 years, p < 0.001). Gender distribution differed markedly between groups (p < 0.001).

2.2. Vitamin D Status and Binding Proteins

In healthy controls, serum vitamin D levels showed expected seasonal variation (

Table 1). Total 25(OH)D was significantly higher in summer (75.0 ± 22.8 nmol/L) compared to winter (44.1 ± 17.8 nmol/L,

p < 0.001). Similarly, free 25(OH)D increased seasonally from 1.7 ± 1.3 pmol/L in winter to 3.0 ± 1.9 pmol/L in summer (

p < 0.001), and bioavailable 25(OH)D from 7.4 ± 5.7 nmol/L to 13.1 ± 8.3 nmol/L (

p < 0.001). VDBP levels remained relatively stable between seasons (239.9 ± 141.9 mg/L in winter vs. 236.9 ± 164.4 mg/L in summer,

p = 0.549), while albumin showed a minor but statistically significant seasonal increase (48.0 ± 3.9 g/L vs. 49.4 ± 4.2 g/L,

p = 0.028).

In contrast, HCC patients exhibited persistently low vitamin D fractions year-round without significant seasonal increase. Total 25(OH)D in HCC (39.3 ± 22.1 nmol/L) was comparable to winter controls (p = 0.061) but markedly lower than summer controls (p < 0.001). Remarkably, free 25(OH)D in HCC patients showed markedly elevated values (27.3 ± 22.3 pmol/L, p < 0.001 vs. both seasons in controls), likely reflecting severe albumin and VDBP depletion. Bioavailable 25(OH)D in HCC was significantly lower than in summer controls (8.5 ± 6.3 vs. 13.1 ± 8.3 nmol/L, p < 0.001) but not significantly different from winter controls (p = 0.183).

VDBP and albumin concentrations were substantially reduced in HCC patients. VDBP in HCC (177.3 ± 237.0 mg/L) was significantly lower than in winter controls (239.9 ± 141.9 mg/L, p < 0.001) and summer controls (236.9 ± 164.4 mg/L, p < 0.001). Albumin in HCC (35.9 ± 5.4 g/L) was significantly lower than in both seasons of controls (winter: 48.0 ± 3.9 g/L; summer: 49.4 ± 4.2 g/L; both p < 0.001).

2.3. Disease Aetiology and Clinical Staging

HCC aetiology distribution included alcoholic liver disease (28 patients; 25/3 male/female), HBV (3 patients; 1/2 male/female), HCV (5 patients; 4/1 male/female), hemochromatosis (1 patient; 1/0 male/female), metabolic liver disease (6 patients; 6/0 male/female), cryptogenic cirrhosis (2 patients; 2/0 male/female), and primary biliary cholangitis (1 patient; 0/1 male/female). Gender distribution across aetiology groups differed significantly (

p = 0.031). Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging revealed stage 0 in 2 patients, stage 1 in 9 patients, stage 2 in 27 patients, stage 3 in 4 patients, and stage 4 in 2 patients, with significant differences in stage distribution across aetiologies (

p = 0.012). Distribution across aetiologies and cancer stages is detailed in

Table 2.

2.4. Correlation Analyses

Strong positive correlations were identified between VDBP and albumin (ρ = 0.395, p = 0.007) and between VDBP and total 25(OH)D (ρ = 0.347, p = 0.018). Notably, VDBP showed robust negative correlations with free 25(OH)D (ρ = -0.606, p < 0.001) and bioavailable 25(OH)D (ρ = -0.541, p < 0.001), reflecting the inverse relationship between carrier protein availability and the free hormone fraction.

Albumin correlated positively with VDBP (ρ = 0.395, p = 0.007) and negatively with both free 25(OH)D (ρ = -0.327, p = 0.026) and Child-Pugh score (ρ = -0.565, p < 0.001), indicating that albumin depletion reflects advancing liver dysfunction.

Total 25(OH)D showed positive correlations with both free 25(OH)D (ρ = 0.463, p = 0.002) and bioavailable 25(OH)D (ρ = 0.476, p = 0.001). Free and bioavailable 25(OH)D were very strongly correlated (ρ = 0.971, p < 0.001), validating their mathematical interdependence.

Child-Pugh score correlated negatively with albumin (ρ = -0.565,

p < 0.001) and positively with BCLC stage (ρ = 0.378,

p = 0.012), confirming the expected relationship between hepatic synthetic function, disease severity, and tumour burden. Significant correlations between vitamin D metabolites, binding proteins, and clinical measures are summarized in

Table 3.

3. Discussion

3.1. Principal Findings and Interpretation

This study demonstrates profound alterations in vitamin D metabolism in HCC, characterized by significantly reduced total, free, and bioavailable 25(OH)D fractions despite markedly elevated calculated free 25(OH)D values in the context of severe albumin and VDBP depletion [

9,

40]. The paradoxically high free 25(OH)D reflects the mathematical consequence of extreme protein binding partner depletion rather than true vitamin D sufficiency. In healthy individuals, approximately 85–90% of circulating 25(OH)D is bound to VDBP, 10–15% is albumin-bound, and less than 1% exists as truly free hormone [

9,

40,

41]. VDBP acts as a reservoir and prolongs the half-life of circulating 25(OH)D, and this critical transport function is severely compromised in HCC. Our HCC patients exhibited dramatically reduced VDBP (177.3 ± 237.0 mg/L vs. 239.9 ± 141.9 mg/L in winter controls,

p < 0.001) and albumin (35.9 ± 5.4 g/L vs. 48.0 ± 3.9 g/L,

p < 0.001), indicating that despite mathematically higher free fractions, the absolute pool of vitamin D available to tissues remains critically compromised. This disruption aligns with the "free hormone hypothesis," which posits that only bioavailable fractions can cross cell membranes and activate vitamin D receptors (VDR) in target tissues [

18,

19].

Unlike healthy controls, who exhibited robust seasonal increases in all vitamin D fractions (total 25(OH)D rising from 44.1 ± 17.8 nmol/L in winter to 75.0 ± 22.8 nmol/L in summer,

p < 0.001), HCC patients showed minimal seasonal variation (total 25(OH)D: 39.3 ± 22.1 nmol/L with no significant change across seasons,

p = 0.549 for season effect). This absence of seasonal responsiveness reflects disease-driven suppression of hepatic 25-hydroxylation and protein synthesis, independent of sun exposure. It indicates that HCC patients have lost their compensatory capacity to respond to environmental vitamin D availability [

7,

30].

3.2. Mechanisms Underlying Vitamin D Perturbation in HCC

Multiple interconnected mechanisms account for the observed vitamin D deficiency in HCC: Hepatic Synthetic Dysfunction: The liver is the primary site of 25-hydroxylation, converting cholecalciferol to 25(OH)D. In HCC and advanced cirrhosis, a reduced hepatic mass, fibrosis, and impaired function (as reflected in Child-Pugh scores and albumin levels) decrease this critical enzymatic step. Our finding that albumin strongly correlates with Child-Pugh score (ρ = -0.565, p < 0.001) underscores the degree of synthetic failure in our HCC cohort.

VDBP and Albumin Suppression: Both VDBP and albumin are hepatically synthesized proteins, and their reduction reflects general hepatic decompensation. Additionally, inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, actively suppress VDBP gene expression [

10,

11]. The negative correlation between VDBP and free/bioavailable 25(OH)D (ρ = -0.606 and -0.541, respectively, both

p < 0.001) suggests that as carrier proteins decline, a higher proportion of remaining vitamin D exists unbound—yet in absolute terms, the total vitamin D pool is depleted, offsetting any theoretical benefit of increased free fraction.

Impaired Systemic Regulation: The absence of seasonal vitamin D variation in HCC, despite controls showing marked seasonal increases, indicates that HCC patients have lost compensatory capacity to respond to increased sun exposure. This likely reflects a combination of reduced 25-hydroxylase activity and possible impaired intestinal absorption due to portal hypertension-related enteropathy or malnutrition [

31,

32].

3.3. Comparison with Prior Studies

Our findings extend and confirm prior investigations into vitamin D metabolism in HCC. Chiang et al. and others documented reduced total 25(OH)D in HCC versus cirrhotic controls [

33,

34]. Critically, Fang et al. demonstrated in a large prospective Chinese cohort that bioavailable 25(OH)D was a superior prognostic marker of HCC survival compared to total vitamin D, even after adjustment for albumin and VDBP [

35]. Their finding that bioavailable fractions predicted outcomes better than total 25(OH)D aligns precisely with our data: bioavailable 25(OH)D (8.5 ± 6.3 nmol/L in HCC vs. 13.1 ± 8.3 nmol/L in controls,

p < 0.001) represents the physiologically active pool available for VDR signalling, whereas total 25(OH)D is inflated by inactive protein-bound fractions when carriers are depleted. Our strong correlation between free and bioavailable 25(OH)D (ρ = 0.971,

p < 0.001) validates their mathematical interdependence and confirms their combined utility as biomarkers.

Bilgen et al. and others have found a vitamin D deficiency to be associated with advanced disease and poor outcomes. However, the evidence remains mixed as to whether this reflects causality or is a marker of overall disease burden [

36,

37]. Our data suggest that vitamin D disruption is primarily a marker of cumulative liver dysfunction rather than an independent causal driver. Supporting this interpretation, the Child-Pugh score (reflecting hepatic synthetic reserve) correlated more strongly with albumin (ρ = -0.565,

p < 0.001) and BCLC stage (ρ = 0.378,

p = 0.012) than vitamin D fractions did independently, indicating that clinical severity drives both vitamin D deficiency and poor outcomes through a common pathway—hepatic reserve decompensation.

3.4. Clinical Implications and Limitations of Current Vitamin D Assessment

Limitations of total 25(OH)D Measurement: Current clinical guidelines typically target a total 25(OH)D level of ≥75 nmol/L or ≥100 nmol/L for optimal bone health and general well-being. However, our data demonstrate that a total 25(OH)D alone is profoundly misleading in HCC. An HCC patient with a total 25(OH)D of 39.3 ± 22.1 nmol/L and severe hypoalbuminemia (35.9 ± 5.4 g/L) and VDBP depletion (177.3 ± 237.0 mg/L) faces compounded vitamin D deficiency at both circulating and bioavailable levels. Yet, calculated bioavailability equations using depleted carrier proteins yield paradoxically elevated free fractions, creating diagnostic confusion. Direct measurement of free 25(OH)D by equilibrium dialysis would provide clarity but is rarely performed clinically.

Superior Utility of Free and Bioavailable Fractions: The strong correlations between VDBP/albumin and bioavailable 25(OH)D (ρ = -0.541 and -0.327, respectively,

p < 0.001), combined with the clinical associations with Child-Pugh class and BCLC stage, suggest that vitamin D fraction measurements could substantially enhance risk stratification in HCC [

40,

41]. Serial monitoring of free and bioavailable 25(OH)D alongside clinical staging might detect transitions in hepatic reserve or inflammatory burden earlier than traditional markers alone. However, the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes assessment of these prognostic relationships; longitudinal follow-up is necessary.

Personalized Supplementation: Vitamin D supplementation guided solely by total 25(OH)D targets may be inadequate or even harmful in HCC. Patients with severely depleted VDBP or albumin might require lower supplementation doses to avoid toxicity, or conversely, might need higher dosing to achieve adequate free/bioavailable vitamin D. Our data support the development of vitamin D dosing algorithms that incorporate binding protein and albumin status.

3.5. Study Strengths

This study possesses several important strengths: (1) Comprehensive simultaneous measurement of all physiologically relevant vitamin D fractions (total, free, bioavailable) alongside their principal carrier proteins (VDBP, albumin) in a well-characterized HCC cohort (n=46) compared to healthy controls (n=87). (2) Dual-season design enabling assessment of environmental (sun exposure) versus disease-related determinants of vitamin D status. The striking absence of seasonal variation in HCC, despite robust seasonal increases in control isolates suggests disease-driven mechanisms. (3) Detailed clinical staging and correlations with established metrics of hepatic reserve (Child-Pugh score, ρ = -0.565 with albumin) and tumour burden (BCLC stage, ρ = 0.378 with Child-Pugh), integrating vitamin D findings with clinical disease severity. (4) Application of validated equations for calculating free/bioavailable 25(OH)D based on measured VDBP, albumin, and total 25(OH)D, with binding affinities derived from published literature and previously validated in large epidemiological cohorts [

29,

41]. (5) Integration of mechanistic literature linking vitamin D pathway dysregulation (VDR suppression, CYP24A1 upregulation) to HCC biology, supporting interpretation of observed biochemical patterns.

3.6. Study Limitations

Key limitations merit acknowledgement: (1) Cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and limits longitudinal outcome assessment. We cannot determine whether vitamin D depletion contributes to HCC progression, serves as a prognostic marker, or is merely an epiphenomenon of hepatic dysfunction. (2) Calculated rather than directly measured free/bioavailable 25(OH)D. Although validated equations employing measured VDBP and albumin were used, direct measurement by equilibrium dialysis or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with mass spectrometry would provide greater accuracy, particularly in extreme hypoalbuminemia. (3) Moderate sample size with single-center recruitment, potentially limiting generalizability to other geographic, ethnic, or healthcare settings. The HCC aetiology distribution (predominantly alcoholic liver disease, with fewer HBV and HCV cases) reflects local referral patterns and may not represent global HCC epidemiology. (4) Incomplete assessment of potential confounders such as dietary vitamin D intake, occupational and leisure sunlight exposure, use of vitamin D supplements or skincare products, and genetic VDBP polymorphisms (Gc1f, Gc1s, Gc2). While we stratified by season, individual-level variability in sun exposure was not quantified. (5) No direct clinical outcome assessment. In our study we measured associations between vitamin D fractions and clinical disease severity markers (Child-Pugh, BCLC) but did not assess survival, time-to-progression, treatment response, or immune parameters (IL-6, TNF-α, regulatory T cells). Longitudinal follow-up with outcome data is essential to validate vitamin D fractions as independent prognostic biomarkers. (6) Potential survivor bias if sicker patients were less likely to participate in the study, though this is mitigated by enrolment of consecutive patients across all BCLC stages (0–4) with representation of both early and advanced disease.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population and Design

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted at University Medical Centre Ljubljana between 2022 and 2024. The study enrolled 46 patients with biopsy-proven or imaging-confirmed HCC according to EASL/EORTC criteria and 87 age-stratified healthy controls. Blood samples were collected during winter (December–February) and summer (June–August) seasons to assess seasonal variations in vitamin D metabolism.

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

HCC patients were eligible if they had a confirmed diagnosis, were at least 18 years old, and had complete clinical and laboratory data available. Exclusion criteria included severe concurrent renal dysfunction (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2), acute infection or sepsis within 4 weeks of sampling, or active use of vitamin D analogues or pharmacological doses of cholecalciferol within 3 months prior to enrolment.

4.3. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committee of University Medical Centre Ljubljana. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

4.4. Clinical Data Collection

For HCC patients, the following clinical data were recorded: age, gender, aetiology of liver disease (alcoholic, hepatitis B virus [HBV], hepatitis C virus [HCV], hemochromatosis, metabolic, cryptogenic, primary biliary cholangitis [PBC]), Child-Pugh score, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, and time since HCC diagnosis.

4.5. Biochemical Measurements

Serum samples were collected by venepuncture in the morning after an overnight fast. All samples were processed and stored at -80°C until analysis.

Measurements were performed at the Clinical Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Biochemistry (University Medical Centre, Ljubljana). 25(OH)D

3, S-albumin and S-DBP in serum, were measured in all participants using the following methods: The concentration of 25(OH)D

3 vitamin was measured using competitive luminescent immunoassay with intra-laboratory CV < 6 % and the limit of quantification 6 nmol/L (Architect analyser, Abbott Diagnostics, Lake Forest, USA), ADVIA® 1650 Chemistry Albumin BCP Assay (Siemens, New York, USA) [

26], Human Vitamin D Binding Protein was measured with ELISA (MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), the limit of quantification was 31 mg/L [

27]. These methods adhere to recognized standards, ensuring reproducibility and validity, as outlined in recent quality control and standardization initiatives for vitamin D measurements. Liver function and Child-Pugh class were recorded for all HCC patients at the time of index sampling. Free and bioavailable 25(OH)D concentrations were calculated using the modified Vermeulen equation, incorporating measured total 25(OH)D, VDBP, and albumin concentrations, with binding affinities established in prior literature [

28]. These calculations reflect physiologically available vitamin D fractions accessible to tissue receptors.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. Given the non-normal distribution of key variables (as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test), the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons between groups and seasons. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was employed to assess associations between continuous variables. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (1 New Orchard Road, Armonk, New York 10504-1722, United States).

5. Conclusions

Vitamin D metabolism is profoundly disrupted in HCC, with severe reductions in total, free, and bioavailable 25(OH)D fractions occurring concurrently with depleted VDBP and albumin levels, which reflect hepatic synthetic dysfunction. The absence of seasonal vitamin D variation in HCC patients, in stark contrast to healthy controls, demonstrates that this disruption is a disease-driven phenomenon reflecting impaired hepatic 25-hydroxylase activity, inflammatory suppression of carrier protein synthesis, and dysregulation of vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes—not merely reduced sun exposure.

Measurement of free and bioavailable 25(OH)D alongside VDBP and albumin may provide a superior assessment of functional vitamin D status and hepatic reserve compared to total 25(OH)D measurement alone. Integration of these biomarkers with clinical staging (Child-Pugh, BCLC) could enhance risk stratification in HCC. These fractions warrant prospective validation as independent risk factors for HCC progression, mechanistic investigation of their relationships to VDR-mediated antitumor immunity, and evaluation as targets for intervention to improve outcomes in liver cancer.

Future research should include: (1) randomized controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation strategies titrated to free/bioavailable 25(OH)D targets with survival and quality-of-life endpoints; (2) investigation of VDBP genetic polymorphisms and their influence on vitamin D bioavailability and HCC outcomes; (3) mechanistic studies of VDR signalling and antitumor immunity as a function of free 25(OH)D levels; and (4) integration of vitamin D fractions with inflammatory cytokine panels (IL-6, TNF-α) and immune cell analysis to construct multidimensional metabolic-immune risk scores for HCC prognostication and personalized therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and J.O.; Methodology, D.S., M.R., M.Z., S.Š., B.Š., A.J., and J.O.; Software, D.S.; Validation, J.O.; Formal Analysis, D.S., and J.O.; Investigation, D.S., M.R., M.Z., S.Š., B.Š.; Data Curation, D.S., M.R., M.Z., S.Š., B.Š., A.J., and J.O.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.S.; M.R., and J.O.; Writing—Review and Editing, B.Š., and J.O.; Visualization, J.O.; Supervision, B.Š. and J.O.; Project Administration, D.S. and J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee approved the study protocol for Human Research of the Medical Ethics Commission of the Republic of Slovenia (Protocol ID: 0120-60/2021/5, 22 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients gave written informed consent for this study before inclusion.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 25(OH)D |

25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| BCLC |

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer |

| HBV |

hepatitis B virus |

| HCC |

hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV |

hepatitis C virus |

| PBC |

primary biliary cholangitis |

| VDBP |

vitamin D-binding protein |

| VDR |

vitamin D receptor |

References

- Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, et al. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–357. [CrossRef]

- Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:684–700. [CrossRef]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D: Production, metabolism, and mechanisms of action. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com; 2017.

- Chiang KC, Chen TC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma cells express 25OHD-1-hydroxylase and are able to convert 25OHD to 1,25OH2D, leading to the 25OHD-induced growth inhibition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;154:47–52. [CrossRef]

- Luderer HF, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with worse clinical outcomes in HCC. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:823–827.

- Nazir A, et al. Vitamin D status and liver disease severity in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:277–288.

- Bikle DD, et al. Vitamin D binding protein and its roles in calcium, vitamin D and mineral homeostasis. Endotext. 2017.

- Speeckaert MM, et al. Vitamin D binding protein: A multifunctional protein of clinical importance. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52:336–349.

- Schwartz JB, et al. Free 25(OH) vitamin D levels are more predictive of vitamin D effects than total 25(OH)D levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:3278–3288.

- Viapiana O, et al. Vitamin D and liver disease. Vitam Horm. 2025;130:289–315.

- Liu S, et al. IL-6 suppresses hepatic vitamin D binding protein expression in chronic inflammation. Cancer Lett. 2022;546:215825.

- Trépo E, et al. TNF-α modulates vitamin D metabolism in hepatic stellate cells. Cancer Lett. 2017;384:89–99.

- Fang AP, Long JA, Zhang YJ, et al. Serum Bioavailable, Rather Than Total, 25-hydroxyvitamin D Levels Are Associated With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival. Hepatology. 2020;72:169-182. [CrossRef]

- Finkelmeier F, Kronenberger B, Köberle V, et al. Severe 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency identifies a poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma - a prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1204-1212. [CrossRef]

- Sollid ST, Hutchinson MY, Berg V, et al. Effects of vitamin D binding protein phenotypes and vitamin D supplementation on serum total 25(OH)D and directly measured free 25(OH)D. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174:445-452. [CrossRef]

- Bikle DD, Schwartz J. Vitamin D Binding Protein, Total and Free Vitamin D Levels in Different Physiological and Pathophysiological Conditions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:317.

- Pop TL, Sîrbe C, Benţa G, Mititelu A, Grama A. The Role of Vitamin D and Vitamin D Binding Protein in Chronic Liver Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:10705. [CrossRef]

- Bikle DD, Bouillon R, et al. Vitamin D metabolite metabolism and action in liver disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:105–116.

- Bikle D. Nonclassical actions of vitamin D. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25469–25476.

- Barrea L, et al. Vitamin D and metabolic disorders: an overview. Nutrients. 2022;14:214.

- Zhu A, et al. Vitamin D binding protein as a prognostic marker in cancer. Nutrients. 2022;14:3894.

- Gaksch M, et al. The association between vitamin D level and hospital mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3131–3144.

- Louka ML, et al. Free and bioavailable vitamin D predict mortality better than total 25(OH)D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:105–116.

- Fang AP, et al. Serum bioavailable and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and overall and liver cancer–specific survival in patients with HCC. Hepatology. 2020;71:1056–1069.

- Bilgen A, et al. Effects of vitamin D level on survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology Forum. 2020;1:105–110. [CrossRef]

- DiaSorin. LIAISON® 25 OH Vitamin D TOTAL Assay. Saluggia, Italy: DiaSorin SpA; 2020.

- R&D Systems. Human VDBP/GC-globulin Quantikine ELISA Kit. Minneapolis, MN: R&D Systems, Inc.; 2022.

- Siuka D, Rakusa M, Vodenik A, et al. Free and Bioavailable Vitamin D Are Correlated with Disease Severity in Acute Pancreatitis: A Single-Center, Prospective Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:5695. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. [CrossRef]

- Heaney RP. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1535–1541.

- Sort P, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403–409. [CrossRef]

- Ginès P, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1646–1654.

- Chiang KC, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in HCC and cirrhotic patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1597–1604.

- Chen TC, et al. Vitamin D metabolism and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R255–R270.

- Fang AP, et al. Prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese cohort. Hepatology. 2020;71:1056–1069.

- Männistö V, et al. Low serum vitamin D and incident advanced liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:271–279.

- Feldman D, et al. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–357. [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Version 2.2024. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2024.

- Holick MF, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930. [CrossRef]

- Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1991–2000. [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh P, Shapses SA, Wang X. Vitamin D binding protein impact on 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1591–1598.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).