1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a type of primary liver malignancy. The majority (90%) of primary liver cancer cases are attributed to HCC. [

1,

2] Worldwide, HCC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in adults. According to the World Health Organization´s (WHO) Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), a total of 905,677 new cases of liver cancer and 830,180 deaths due to liver cancer were recorded in 2020. [

3] Liver cancer is currently the sixth most common cancer worldwide. It is predicted that the number of new cases of primary liver cancer will rise drastically between 2020 and 2040. 1.4 million new diagnoses are anticipated to occur in 2040. [

4]

In Austria specifically, a total number of 1,114 new liver cancer cases were documented in the 2020 GLOBOCAN database, with 993 deaths reported. Liver cancer ranked as the 14

th most commonly diagnosed cancer and obtained the 6

th place for highest number of deaths caused by cancer in Austria. [

5] Between 2010 and 2018 a total of 7,146 individuals were diagnosed with HCC in Austria, of which 75% were male and 25% were female. [

6]

HCC mainly develops in the setting of underlying liver cirrhosis. [

1] Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is still the leading underlying cause of HCC globally, due to its high prevalence in Asia and Africa. [

1] In the West, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), associated with metabolic lifestyle diseases, are rapidly becoming major role-players in the aetiological development of HCC. [

2]

HCC may develop without the presence of liver cirrhosis in an estimated 20-30% of NASH cases. [

7] Chronic alcohol use disorder is a well-known risk factor for liver cirrhosis. The estimated risk to develop HCC in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to alcohol use is around 1% per year. [

8] In Austria, alcohol remains the predominant cause of liver cirrhosis. According to the textbook of alcohol in Austria, the number of hospital admission for alcohol dependency have however steadily declined over the past decade. [

9]

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC)-system is the most frequently used staging tool in clinical practice today. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends the updated BCLC-staging system for the prediction of prognosis and the allocation of appropriate treatment. [

10] Major advances in the systemic medical treatment of HCC have been made over the past decade. Between 2018 and 2019, the IMbrave150 trail compared Sorafenib to the Atezolizumab/ Bevacizumab combination and proved a better overall survival rate with the latter treatment strategy. [

11]

In this study we aimed to investigate the changes observed in the epidemiology and aetiology of HCC at Klinikum Klagenfurt between 2012 and 2023 (Klinikum Klagenfurt is the third biggest hospital in Austria and situated in the province of Carinthia. It is affiliated with the Medical University of Graz, Innsbruck and Vienna and offers approximately 1,400 beds). The survival of HCC patients was investigated for a number of different variables. By analysing the epidemiological data, we hope to have a better understanding of HCC in our community and use this knowledge to improve prevention strategies and aid in better detection and treatment of HCC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data retrieval

This was a single-centre cohort study at Klinikum Klagenfurt am Wörthersee in Austria. Data was obtained retrospectively from the hospital’s clinical information software system known as Orbis and the laboratory results were acquired from the electronic system, Lauris.

Two time-periods were established in order to evaluate the changes in epidemiology and survival. The first time-period included all patients diagnosed with HCC from January 2012 until the end of 2017 and the second comprised of patients diagnosed between the beginning of 2018 until February 2023. In 2018 a marked change in the systemic medical management of HCC started to take place and therefore 2018 was used as the cut-off for comparison.

Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by means of radiology (ultrasound, CT, MRI), laboratory parameters according to Baveno, Fibroscan or histologically.

All patients above the age of 18 years diagnosed with HCC either histologically by means of a liver biopsy or through multi-phase imaging techniques (quadruple-phase CT or contrast enhanced MRI) were captured in our data collection. Patients with mixed HCC and biliary tract cancers (BTCs) and patients with missing data vital to our study aim were excluded from our study population.

2.2. Statistics

The IBM SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyse the captured data from the selected patient population. Nominal data was given as absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) and numerical data was presented as the median with the standard deviation range included. Pearson´s Chi-square test was applied to analyse categorical data and to determine how likely it was for differences between data sets to occur due to chance. A p-value of <0.050 was seen as statistically significant. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate and analyse survival probability. First the survival of all HCC patients was evaluated, then the statistical analysis was repeated, after removing all patients who underwent an OLT from the calculations.

3. Results

From January 2012 to February 2023, a total of 285 patients were diagnosed with HCC. 276 patients met the requirements of the inclusion criteria and were taken into account for further statistical analysis.

3.1. Descriptive patient analysis and time-period comparison (table 1):

The first time-period consisted out of 128 patients (46.4% of the total patient population) and the second out of 148 patients (53.6%). The incidence rate was 5.9 times higher in males than in females. In the first time-period, the median age of diagnosis was 73 years (SD 8.6) compared to 71 years (SD 8.5) in the second time-period (p = 0.042).

During the first time-period, 22 patients (17.2% of total patients within time category) had HCC without underlying liver cirrhosis. This number increased to 47 (31.8%) during the second time-period (p = 0.005).

Alcoholic liver disease was the most common underlying aetiology with a total of 139 patients (55.6%). 55 patients (22%) had viral hepatitis and 43 (17.2%) had underlying NASH. A total of 13 patients (5.2%) were classified as “other” (e.g. hemochromatosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome and primary biliary cholangitis.). There was no statistically significant change observed in the aetiology of HCC between the two time-categories (p = 0.353).

The alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) values were documented for 272 patients. A total of 116 patients (42.6%) had unelevated AFP levels (< 7 ng/mL) and 156 (57.4%) had a raised AFP (≥ 7 ng/mL) level at the time of diagnosis. No difference could be observed between the aetiologies. Only 66 patients (24.3%) had an elevated AFP level ≥ 200 ng/mL, and 56 patients (20.6%) had an AFP level of ≥ 400 ng/ml. No significant change in AFP-levels was observed over time (p = 0.199), despite the shift in aetiology of the underlying liver disease.

Concerning the Child-Pugh scoring system, a total of 116 patients (42%) were classified as Child-Pugh A.

With regards to tumor staging, the majority of patients (40.6%, n = 112) were classified as BCLC-A at the time of diagnosis. The number of patients diagnosed at the advanced stage BCLC C increased over time (p = 0.051).

Regarding the ALBI score, 30.6% (

n = 83) of HCC patients were staged as ALBI grade 1. Significantly more patients were staged as ALBI grad 1 in the second time period (

p < 0.001,

Table 1).

There was no noteworthy change in histological grading over time (p = 0.196).

The median size of the largest space-occupying lesion was 4.5 cm in both time periods.

No statistically significant difference in the incidence of portal-vein thrombosis, macrovascular invasion, enlarged lymph-nodes or distant metastases was observed over time.

Concerning comorbidities, no significant change was seen over time. The mean body mass index (BMI) for all patients was 28 (SD 4.5). The mean BMI of HCC patients at the time of diagnosis did not change over time (p = 0.871).

In our patient population, a total of 7 orthotopic liver transplantations (OLTs) were performed in the first time-period and 6 in the second (p = 0.580).

Regarding first-line therapy for all patients, 11.3% (n = 31) underwent surgical treatment, 48% (n = 132) had interventional therapy, 26.2% (n = 72) received systemic treatment and 14.5% (n = 40) received best supportive care/ no treatment.

While surgical treatment remained stable over time, there was a significant shift from interventional to systemic treatments from the first to the second observation period (

p < 0.001). Moreover, the number of patients who received any kind of treatment increased significantly (

Table 1).

For reasons of drug approval in the EU, treatment with immuno-therapy was more frequent in the second time period.

In a more detailed look at BCLC-B patients specifically, a treatment migration away from surgical/ interventional treatment towards more systemic therapy was evident. The shift in surgical treatments in BCLC-B patients (in the first time period 4 (12.5%) patients compared to 2 (6.9%) patients in the second time-period) can hardly be statistically evaluated due to the low number of patients, for surgery is not a standard treatment in BCLC-B patients. But 26 (81.3%) patients received ablative/ interventional therapy in the first time-period, compared to 11 (37.9%) patients in the second (p<0.001) and only 2 (6.3%) patients received systemic drug treatment in the first time-period, compared to 16 (55.2%) patients in the second (

p < 0.001,

Table 1).

3.2. Univariate analysis of median survival times (table 2):

The median overall survival was 20.5 months with 21.9 months (95% CI 17-26.8) in the first time-period and 20.2 months (95% CI 15.7-24.6) in the second time-period (p = 0.841).

When patients who underwent OLTs were removed from the analysis, the median overall survival was 19.4 months (95% CI 15.9-22.9), with no significant change between the two time-intervals (p = 0.902).

The median OS for HCC patients without liver cirrhosis was 22 months (95% CI 8.7-35.7) and those with cirrhosis had an OS of 20.2 months (95% CI 16.9-23.4, p = 0.262). No significant change in survival time for cirrhotic vs. non-cirrhotic patients were found between time-periods (p = 0.279). Looking at patients with early stage (BCLC-A) HCC and advanced stage (BCLC-C) separately, OS in the first period for BCLC-A was 33.1 months (95% CI 11.2-55.1) and in the second period was 53 months (95% CI 20.1-85.5; p = 0.805). The OS for BCLC-C in the first time period was 10.4 months (95% CI 5.9-15) and 10 months in the second time period (95% CI 6.2-14, p = 0.446).

No significant difference in overall survival for patients with cirrhosis versus non-cirrhosis in BCLC-A and BCLC-C respectively was found (p = 0.977; p = 0.449).

29 (42%) patients without liver cirrhosis and 83 (40.1%) with liver cirrhosis were staged as BCLC-A. 24 (34.8%) of non-cirrhotic patients and 45 (21.7%) of those with liver cirrhosis were staged as BCLC-C.

Regarding survival and aetiology, patients with alcohol as underlying cause had the shortest median OS of 18.1 months (95% CI 14.2-22). Those with viral hepatitis had a median OS of 32.2 months (95% CI 15.9-48.3). Patients with NASH had a median OS of 38.7 months (95% CI 18.4-59) and those with other causes had a median OS of 19.7 months (95% CI 0-53.7, p = 0.004). No difference in OS for alcohol (p = 0.772), viral (p = 0.868) or NASH (p = 0.970) as underlying aetiology was found in cirrhotic compared to non-cirrhotic patients.

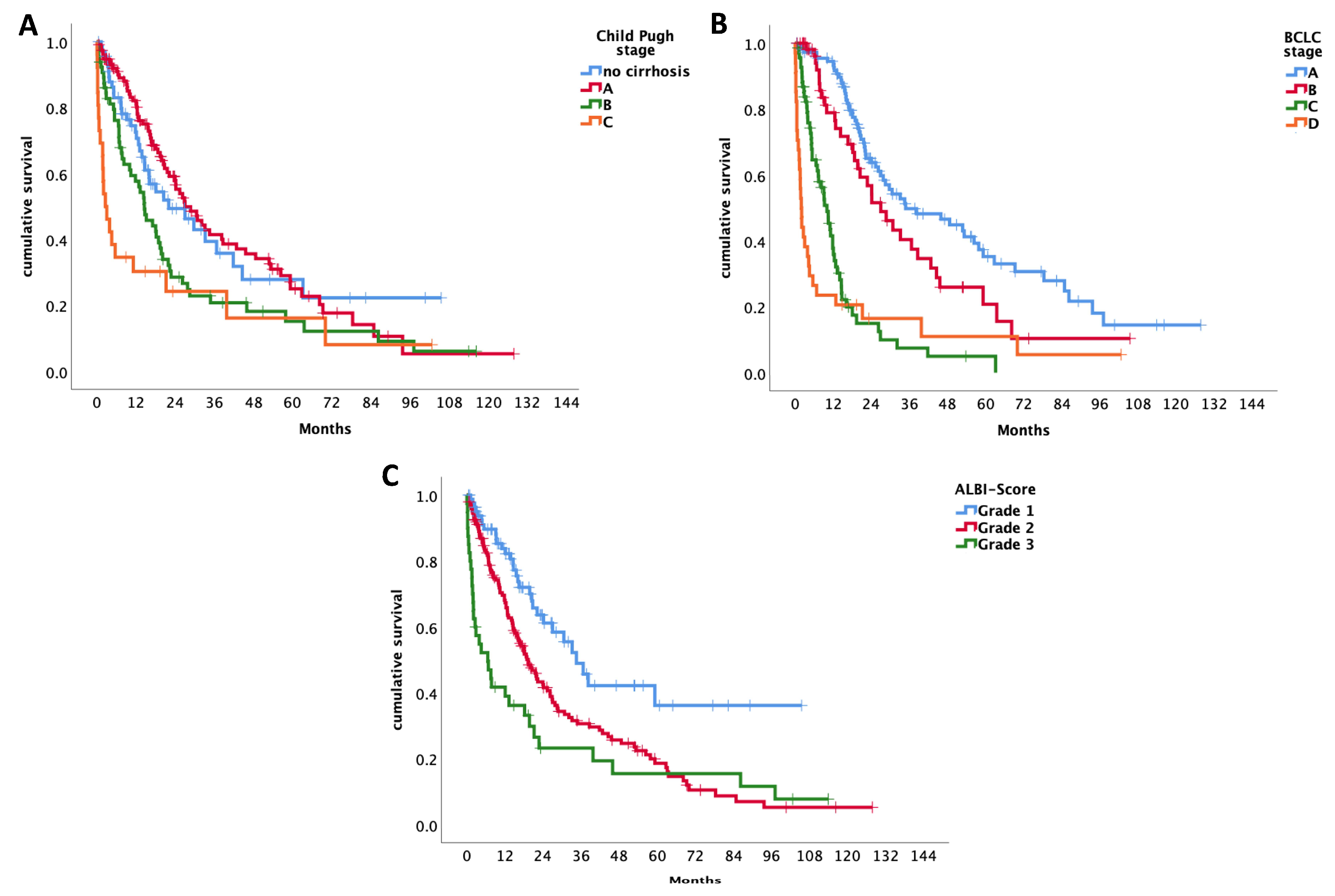

According to the Child-Pugh classification, the median OS for patients staged as Child-Pugh A was 27 months (95% CI 19.4 -34.6), for Child-Pugh stage B 14.6 months (95% CI 10.1-19) and 2.6 months (95% CI 0.2-5) for Child-Pugh C (

p < 0.001).

(See

Figure 1A

)

Patients with BCLC-A had a median OS of 34.9 months (95% CI 15.8-53.9), those with BCLC-B had 27 months (95% CI 17.9-36.2), BCLC-C had 10 months (95% CI 7.3-12.8) and BCLC-D a median OS of 1.9 months (95% CI 1.3-2.6) (

p < 0.001).

(See Figure 1B)

Concerning the ALBI-score, patients graded as ALBI 1, had a median survival time of 34.6 months (95% CI 26-34.1). For patients classified as ALBI grade 2, the median survival time was 19.4 months (95% CI 15.1-23.6) and 6.6 months (95% CI 1-12-2) for ALBI grade 3. There is a significant change over time for survival of the various ALBI grades (

p < 0.001).

(See Figure 1C)

Patients with a normal AFP level (< 7) had a median survival time of 34.6 months (95% CI 22.8-46.3) and those with a raised AFP above 7 had a 14.6-month median survival time (95% CI 10.3-18.9). Patients with an AFP serum level > 7 and ≤ 200 ng/mL had a median survival time of 20.7 months (95% CI 16.1-25.4). Those with an AFP > 200 and ≤ 400 had a median survival time of 5.2 months (95% CI 3.2-7.2) and those with an AFP ≥ 400, a 7.3 month (95% CI 4.4-10.3) survival time (p < 0.001).

The median survival time for those who fulfilled the Up-to-seven criteria (≤ 7 points) was 33.1 months (95% CI 17.9-48.4), while those with > 7 points had a median survival time of 11.8 months (95% 9.6-14.1, p < 0.001).

There was no significant difference in OS observed in the different comorbidities or concomitant medication.

3.3. Statistical analysis of HCC patients without liver cirrhosis (table 3):

The number of patients diagnosed with HCC, where no liver cirrhosis was present increased from the first time-interval to the second. A more in-depth look at the specific characteristics of this patient group in the overall cohort was taken, in order to better understand why this phenomenon occurred.

The male to female ratio and median age was similar in the non-cirrhotic cohort compared to the cirrhotic cohort.

With regards to aetiology in non-cirrhotic patients, 7 patients (15.2%) were known with alcoholic liver disease, 14 patients (30.4%) had underlying viral hepatitis, 23 (50%) had NASH and 2 patients (4.3%) were classified as other. In patients with liver cirrhosis, 64.7% (n = 132) of patients had underlying alcoholic liver disease, 20.1% (n = 41) had viral hepatitis, 9.8% (n = 20) had NASH and 5.4% (n = 11) of patients were classified as other (p < 0.001).

The largest percentage of patients were staged as BCLC-A (42%). 21.7% were classified as BCLC-B, 34.8% (n = 24) as BCLC-C and 1.4% (n = 1) as BCLC-D, with was in clear contrast to cirrhotic patients (p = 0.006).

Only 47.1% (n = 32) of patients without cirrhosis had a raised AFP (≥7) compared to 60.8% (n = 124) of patients with cirrhosis who had a raised AFP level (p = 0.047).

The Fibrosis-4 score was calculated for all non-cirrhotic patients to estimate the severity of fibrosis. Out of the 69 patients, 6 (8.7%) had mild fibrosis, 24 (34.8%) had moderate fibrosis and 39 (56.5%) had severe fibrosis.

The median largest space-occupying lesion size was 5.3 cm (SD 3.4) in non-cirrhotic patients, compared to 4 cm (SD 3.7) in cirrhotic patients (p = 0.149).

11 patients (15.9%) had PVT at the time of diagnosis, 9 patients (13%) had distant/ extra-hepatic metastases, 13 patients (18.8%) had MVIs, 13 patients (18.8%) had enlarged lymph-nodes (> 2 cm) and 9 (13%) had SBLs. Patients without liver cirrhosis, predominantly (68.1%) had lesions restricted to one lobe of the liver.

With the exception of arterial hypertension, there was no difference in comorbidities between patient with and without cirrhosis.

Surgical treatments and systemic therapies including Immuno-therapy was significantly more often performed in non-cirrhotic patients, while interventional treatments were more common in cirrhotic patients (p>0.001).

Table 3.

HCC patients with liver cirrhosis compared to non-cirrhotic patients.

Table 3.

HCC patients with liver cirrhosis compared to non-cirrhotic patients.

| |

|

|

Cirrhosis

(N=207) |

Non-cirrhosis

(n=69) |

|

| Variable |

|

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

p-value |

| Age |

Mean ± STD |

71 ± 8.6 |

73 ± 8.8 |

0.112 |

| Sex |

Male |

178 (86) |

58 (84) |

|

| |

|

Female |

29 (14) |

11 (16) |

0.693 |

| BMI |

Mean ± STD |

28 ± 5.1 |

28 ± 4.8 |

0.699 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aetiology |

|

Alcohol |

132 (65) |

7 (15) |

|

| |

|

Viral |

41 (20) |

14 (30) |

|

| |

|

NASH |

20 (10) |

23 (50) |

|

| |

|

Other |

11 (5) |

2 (4) |

< 0.001 |

| Ascites |

|

Present |

68 (33) |

1 (1) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

136 (67) |

68 (99) |

< 0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| BCLC stage |

|

A |

83 (40) |

29 (42) |

|

| |

|

B |

46 (22) |

15 (22) |

|

| |

|

C |

45 (22) |

24 (35) |

|

| |

|

D |

33 (16) |

1 (1) |

0.006 |

| ALBI score |

|

Grade 1 |

41 (20) |

42 (62) |

|

| |

|

Grade 2 |

124 (61) |

24 (35) |

|

| |

|

Grade 3 |

38 (19) |

2 (3) |

<0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Grading |

|

0/negative |

16 (12.5) |

0 (0) |

|

| |

|

1 |

39 (30.5) |

31 (48) |

|

| |

|

2 |

55 (43) |

26 (40) |

|

| |

|

3 |

17 (13) |

8 (12) |

|

| |

|

4 |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

0.015 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Focality |

|

Unifocal |

88 (42.5) |

39 (56.5) |

|

| |

|

Multifocal |

119 (57.5) |

30 (43.5) |

0.043 |

| SOL (size in cm) |

|

Mean ± STD |

5.4 ± 3.7 |

6.1 ± 3.4 |

0.149 |

| Up-to-seven |

|

≤7 |

110 (53) |

31 (45) |

|

| |

|

>7 |

96 (47) |

38 (55) |

0.223 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Macrovascular invasions |

Present |

45 (22) |

13 (19) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

161 (78) |

56 (81) |

0.597 |

| Enlarged lymph-nodes (>2cm) |

Present |

28 (14) |

13 (19) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

174 (86) |

56 (81) |

0.319 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Coronary artery disease |

Present |

24 (12) |

10 (14.5) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

180 (88) |

59 (85.5) |

0.553 |

| Hypertension |

|

Present |

116 (57) |

51 (74) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

88 (43) |

18 (26) |

0.012 |

| Diabetes |

|

Present |

67 (32) |

21 (30) |

|

| |

|

Absent |

140 (68) |

48 (67) |

0.765 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AFP |

|

Raised (>7) |

124 (61) |

32 (47) |

|

| |

|

Normal |

80 (39) |

36 (53) |

0.047 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| First-line Therapy |

|

Surgical |

15 (7) |

16 (23) |

|

| |

|

Interventional |

109 (53) |

23 (33) |

|

| |

|

Systemic |

45 (22) |

27 (39) |

|

| |

|

None |

37 (18) |

3 (4) |

< 0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| OLT |

|

Yes |

12 (6) |

1 (1) |

|

| |

|

No |

195 (94) |

68 (99) |

0.140 |

| Resection |

|

Yes |

13 (6) |

14 (20) |

|

| |

|

No |

194 (94) |

55 (80) |

0.001 |

| RFA (first-line) |

|

Yes |

49 (24) |

10 (14.5) |

|

| |

|

No |

158 (76) |

59 (85.5) |

0.107 |

| MWA (first-line) |

|

Yes |

14 (7) |

3 (4) |

|

| |

|

No |

193 (93) |

66 (96) |

0.470 |

| TACE (first-line) |

|

Yes |

86 (41.5) |

16 (23) |

|

| |

|

No |

121 (58.5) |

53 (77) |

0.006 |

| Immuno-therapy |

|

Yes |

31 (15) |

21 (30) |

|

| |

|

No |

176 (85) |

48 (67) |

0.004 |

4. Discussion

4.1. General statistics discussion

The rising incidence of HCC is a pressing matter globally and continues to place a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Between 1995 and 2015, the documented incidence of HCC rose by 75%, this is especially true for parts of East-Asia. [

12] More patients in our cohort were diagnosed during the second time-period compared to the first, which demonstrates the growing incidence of HCC also in our country. Another possible explanation for this finding could be the fact that

Klinikum Klagenfurt became the main HCC referral centre for HCC during recent years.

We were able to prove that the incidence of HCC remained higher in males compared to females and that there was no significant change in the ratio over time. Advanced age is known to be a risk factor for HCC. This was also true for patients in our study population with the median age of diagnosis being > 72 years. It was interesting to note that patients were on average 2 years younger when diagnosed with HCC in the second time-period. Compared to data collected from the Munich Cancer Register in a study conducted by De Toni et al., where the average age of diagnosis increased between 1998 -2016 from 67.1 to 69.1 years. [

13]

Chronic underlying liver disease and cirrhosis in particular are known to be an important role-player in the development of HCC. The majority of patients did have liver cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis, but the proportion of patients without liver cirrhosis notably increased in the second time-category. Inversely, the number of patients with HCC and liver cirrhosis decreased over time. A retrospective study was also conducted in South America regarding the changing epidemiology of HCC. Here 20% of all patients diagnosed with HCC were found to have no underlying liver cirrhosis. [

14]

Excessive alcohol use is known to be the predominant underlying cause of cirrhosis and HCC in Austria and continued to be the most prevalent aetiology of HCC in our cohort. Viral hepatitis was the second most common underlying cause of HCC and NASH the third. It has been proposed that alcohol-related liver disease is declining in Austria and that NAFLD/ NASH due to obesity and life-style diseases is increasing as a cause of HCC. Even though statistically the aetiology of HCC remained similar over time, an upward trend in the number of NASH cases was clearly evident in the second time-period. In a large, international meta-analysis conducted by Younossi et al., it was estimated that the global incidence of NAFLD is around 25.24% (95% CI: 22.10-28.65) in the general population. [

15] In a study conducted in New-south Wales, Australia, that evaluated the epidemiological trends of HCC, it was also found that there was an increasing number of NAFLD/ NASH-related HCC cases occurring, although not statistically significant at the time. [

16] HBV remains the most important risk-factor for HCC development worldwide, but NASH is quickly rising as an important risk factor in first-world countries, where an estimated 4-22% of HCC cases are due to NAFLD/ NASH. [

17]

Another noteworthy finding was the fact that 42.6% of all patients with HCC in our cohort did not have an elevated AFP level at the time of diagnosis. This emphasizes the fact the AFP cannot be used as a sole, reliable screening factor for HCC. Other studies have also proven that in about 40%-50% of HCC patients no elevated AFP levels were found. [

18]

With regards to the staging and prediction of outcome, most patients were diagnosed as Child-Pugh A in our population. The number of non-cirrhotic patients increased over time and the number of patients classified as Child-Pugh stage B, decreased over time. The percentage Child-Pugh C patients per time period patients stayed similar. Overall, most patients in our population were diagnosed as BCLC-A (early-stage disease), which is quite remarkable compared to most other HCC-cohorts and could be an indication of a functional HCC surveillance-program in our unit. No significant changes over time were observed for this stage. Nonetheless, fewer patients were diagnosed as BCLC-B, more as BCLC-C and a decrease in terminally ill BCLC stage D patients were seen in the second time-category. Overall, the majority of patients were classified as ALBI grade 1. Here a difference was noticeable between the two time-periods as the percentage of patients with ALBI grade 1 increased markedly from the first to the second time-period. Patients with ALBI grade 2 on the other hand decreased significantly over time.

Comorbid life-style diseases are increasing risk-factors for developing a malignant disease like HCC, which is represented in significantly increasing number of patients suffering from NASH. Patients were on average overweight (BMI ≥ 25) at the time of diagnosis, but no change in overall BMI was apparent between the two time-categories.

Many developments were observed in the approach to treating HCC. TACE was the most common first-line treatment modality used overall, but became less popular during the second time-interval. RFA was initially the most used first-line ablation technique, but was switched to MWA over time. A rapid increase in the administration of Immunotherapy was also evident after 2018. There was a significant increase in the percentage of patients who received systemic therapy as part of their treatment regime during the second time-period.

The fact that less patients were staged as BCLC-B and more with BCLC-C in the second time-period caused a treatment migration away from TACE/ interventional therapies and lead to an increasing number of patients being treated with systemic therapy.

4.2. Survival analysis discussion:

Patients in our cohort survived between 20-22 months. Compared to data from De Toni et al., where the median survival of liver cancer patients in Munich between 2008 and 2016 was 12 months. [

13] Men had a longer survival time compared to women. Age did not play a significant role in overall survival time. It is important to note that despite major advances in the systemic medical management of HCC, there still was no significant improvement in the median overall survival time of patients between the two time-periods in our cohort, albeit with a higher fraction of BCLC-stage C patients compared to the earlier period. Despite these findings, OS still improved when compared to data collected in Austria over the past three decades. In a study conducted at the Medical University of Vienna by Schöniger-Hekele et al., it was shown that HCC patients only had a median survival time of 8 months between 1991 and 1998. [

19] Another study performed by Hucke et al. took an even more extensive look at the survival outcomes of all HCC patients in Austria. Here patients diagnosed between 1990-1999, had a mean survival time of 2.6 months (95% CI: 2.3-2.9) and those diagnosed between 2000-2009 had a 5.6-month survival time (95% CI: 5.1-6.1). In the group of patients that were diagnosed with HCC between 2010-2018, the overall survival improved significantly to 9.3 months (

p < 0.001). [

6]

We took a closer look at the survival of patients without liver cirrhosis compared to those with cirrhosis. Even though not proven to be statistically significant, the median survival time of patients without cirrhosis was on average longer than those with cirrhosis. Lack of statistical significance might be due to the fact that we had not enough non-cirrhotic patients in our cohort for a meaningful BCLC stage-specific comparison. A study conducted in East-Asia found the 5-year overall survival rate for non-cirrhotic patients to be 59.5% compared to compared to 37.1% in those with cirrhosis (

p < 0.001). [

20]

In terms of underlying aetiology, patients with NASH had the longest overall survival time. Patients with HCC related to alcohol use, performed the worst and had the shortest survival time, which probably was due to the more advanced stage of cirrhosis in alcohol vs. NASH-patients.

The Child-Pugh and BCLC staging systems correlated with overall survival time, as those staged as A had the longest survival. AFP levels also strongly correlated with survival time, like in numerous previous studies. [

21,

22,

23] Patients with a normal AFP level had the longest survival time, those with AFP levels above 200/400 performed the worst and demonstrated very short survival times.

Comorbidities and concomitant medication did not play a role in OS.

Patients who underwent resection or radiofrequency/ microwave ablation as part of their treatment plan had the best and similar survival rates. Patients on Immunotherapy seemed to have had better outcomes compared to those on traditional Tyrosine-kinase Inhibitors.

4.3. Discussion of non-cirrhotic patients:

An important discovery in our study was the fact that the incidence of HCC in patients without liver cirrhosis is rising.

HCC patients without liver cirrhosis were on average 2 years older at the time of diagnosis, compared to those with cirrhosis. The opposite was found in East-Asia where non-cirrhotic patients tended to be younger than those with cirrhosis. [

20]

A marked difference in the underlying aetiology between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients was detected. Here, the primary cause of HCC was NASH in the first place, viral hepatitis in the second place and underlying alcoholic liver disease in the last place. This stands in contrast to our general population group where alcoholic liver disease was the leading cause of HCC. In East-Asia, HBV is the leading underlying cause of HCC in non-cirrhotic patients. [

20]

Haung et al. described the global epidemiology of HCC related to NAFLD. In their review it was mentioned that patients with underlying NAFLD tended to be older at the time of diagnosis, compared to patients with viral hepatitis as underlying cause. [

24] In a meta-analysis by Stine et al., 34% of patients with NASH-induced HCC had no underlying evidence of liver cirrhosis. [

25] This percentage was higher in our population as NAFLD/ NASH was responsible for half of the HCC cases without underlying cirrhosis.

The majority of patients with NASH were diagnosed as BCLC-A, similar as in our whole collective patient group. In the group without liver cirrhosis, more patients were diagnosed as BCLC-C compared to patients with liver cirrhosis, which was likely due to lack of surveillance in non-cirrhotic patients.

More than half of the patients (52.9%) without liver cirrhosis had a normal/unelevated AFP level at the time of diagnosis, compared to 39.2% of patients with liver cirrhosis. This suggests that AFP levels are even less sensitive in non-cirrhotic patients. In a review done by Desai et al., it was also found that AFP levels were only elevated in 31-67% of non-cirrhotic cases, compared to 63-84% in cirrhotic patients. [

26]

Most patients without cirrhosis in our cohort had severe fibrosis according to the Fib-4 score and histology, which documents that a higher grade of fibrosis and inflammation significantly increases the risk of HCC. In a study published in 2005 by Adams et al. in the USA, most non-cirrhotic patients with NASH-related HCC had stage 0 fibrosis (F0). [

27] In 2018, Kimura et al. from Japan also published a study regarding NASH-related HCC in non-cirrhotic patients. The majority of patients had fibrosis stage 1 (F1) and a 6% cumulative incidence of HCC over 10 years. [

28]

A higher percentage of patients without cirrhosis had unifocal lesions, as opposed to those with cirrhosis, where more patients had multifocal lesions. Larger lesions were present at the time of diagnosis in patients without cirrhosis, again hinting at lack of surveillance in the non-cirrhotic group and later detection of the HCC as a consequence.

The incidence of DM was similar in cirrhotic vs. non-cirrhotic patients in our cohort. Other authors have been able to demonstrate that DM is more prevalent in NAFLD/ NASH. [

29] In our study population, the percentage of overweight patients (BMI ≥ 25) was similar in non-cirrhotic compared to cirrhotic patients. This could also be due to the fact that many of the alcoholic HCC-patients had more advanced stage liver disease with ascites, which would lead to an overestimation of the true “dry” BMI in a retrospective analysis.

The percentage of patients with distant metastases was slightly higher compared to the general cohort, also hinting at later-stage detection of the HCC. Alternatively, a more malignant tumour biology could be postulated for non-cirrhotic patients, but this is neither supported by tumour grading nor by the comparatively low AFP-values. Desai et al. reported that 25% of non-cirrhotic patients had distant metastases at the time of diagnosis [

26], more than the 13% we found in our study.

5. Conclusions

Hepatocellular carcinoma remains a major threat in patients with chronic liver disease. The incidence continues to rise globally despite efforts being made to prevent HCC. This was also in case in our specific cohort.

Changes occurring in the epidemiology of HCC have been noticeable over the past decade. More patients in our cohort were diagnosed without underlying liver cirrhosis in recent years. This group of patients was particularly interesting as it demonstrated a different aetiological pattern compared to HCC patients with underlying liver cirrhosis.

NASH secondary to lifestyle diseases played a bigger role in the development of HCC without cirrhosis compared to alcohol use in cirrhotic patients. This should alert health-care practitioners and policymakers to shift prevention strategies in this direction.

A clear upward trend in the number of patients with NASH was evident in our general study population. NASH remains an important upcoming risk factor for HCC and is already one of the leading causes of HCC in the USA. In about 20-30% of NASH induced HCC, no evidence of liver cirrhosis is found. [

7]

In light of these findings, one could ask the question if there is a need for new screening techniques and prevention strategies as we have demonstrated that the epidemiology of HCC is changing in our population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: ALBI Score Grading for various BCLC Stages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H. and M.P.; methodology, F.H., H.E. and M.P.R..; software, F.H., H.E., R.E. and M.H.; validation, F.H, H.E., R.E., S.B., M.H., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M. and M.P.; formal analysis, F.H., H.E., R.E., M.H.; investigation, F.H, H.E., R.E., S.B., M.H., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M. and M.P.; resources, F.H, H.E., R.E., S.B., M.H., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M. and M.P.; data curation, H.E., R.E.; writing—original draft preparation, F.H., H.E., R.E.; writing—review and editing, F.H, H.E., R.E., S.B., M.H., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M. and M.P.; visualization, F.H., H.E., R.E., M.H.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, F.H.; funding acquisition, F.H, H.E., R.E., S.B., M.H., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was granted approval by the Ethical Committee of Carinthia. Patient data was collected retrospectively and kept confidential by allocating numbers to patient names. Patients consent was therefore waived.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was granted approval by the Ethical Committee of Carinthia. Patient data was collected retrospectively and kept confidential by allocating numbers to patient names. Patients consent was therefore waived.

Data Availability Statement

Data was obtained retrospectively from the Klinikum Klagenfurt am Wörthersees clinical information software system known as Orbis and the laboratory results were acquired from the electronic system, Lauris.

Conflicts of Interest

F.H. has nothing to declare. H.E. has nothing to declare. R.E. has nothing to declare. M.H., S.B., L.d.P., A.K., T.B., M.F., K.H., R.M., M.P. is an investigator for Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Lilly, and Roche; he received speaker honoraria from Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Lilly, MSD, and Roche; he is a consultant for Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Lilly, MSD, and Roche; he received travel support from Bayer and BMS.

References

- Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(15):1450–62.

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021; 7(1):6.

- 11-Liver-fact-sheet [cited 2023 Mar 1]. Available from: URL: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/11-Liver-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol 2022; 77(6):1598–606. [CrossRef]

- 40-austria-fact-sheets [cited 2023 Mar 1]. Available from: URL: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/40-austria-fact-sheets.pdf.

- Hucke F, Pinter M, Hucke M, Bota S, Bolf D, Hackl M et al. Changing Epidemiological Trends of Hepatobiliary Carcinomas in Austria 2010-2018. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14(13). [CrossRef]

- Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, Natarajan Y, Chayanupatkul M, Richardson PA et al. Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018; 155(6):1828-1837.e2.

- Nowak AJ, Relja B. The Impact of Acute or Chronic Alcohol Intake on the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21(24).

- Bachmayer S, Strizek Julian, Uhl Alfred. Handbuch Alkohol - Österreich. Band 1 - Statistiken und Berechnungsgrundlagen. Datenjahr 2021. Gesundheit Österreich, Wien.

- EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 56(4):908–43.

- Cheng A-L, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim T-Y et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2022; 76(4):862–73. [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdel-Rahman O et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5(12):1749–68.

- Toni EN de, Schlesinger-Raab A, Fuchs M, Schepp W, Ehmer U, Geisler F et al. Age independent survival benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) without metastases at diagnosis: a population-based study. Gut 2020; 69(1):168–76. [CrossRef]

- Farah M, Anugwom C, Ferrer JD, Baca EL, Mattos AZ, Possebon JPP et al. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in South America: A report from the South American liver research network. Ann Hepatol 2023; 28(2):100876. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016; 64(1):73–84.

- Joseph Yeoh YK, Dore GJ, Lockart I, Danta M, Flynn C, Blackmore C et al. Temporal change in etiology and clinical characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in a large cohort of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in New South Wales, Australia; 2023.

- Hucke F, Sieghart W, Schöniger-Hekele M, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Müller C. Clinical characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Austria - is there a need for a structured screening program? Wien Klin Wochenschr 2011; 123(17-18):542–51.

- Lee C-W, Tsai H-I, Lee W-C, Huang S-W, Lin C-Y, Hsieh Y-C et al. Normal Alpha-Fetoprotein Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Are They Really Normal? J Clin Med 2019; 8(10).

- Schöniger-Hekele M, Müller C, Kutilek M, Oesterreicher C, Ferenci P, Gangl A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Central Europe: prognostic features and survival. Gut 2001; 48(1):103–9. [CrossRef]

- Yen Y-H, Cheng Y-F, Wang J-H, Lin C-C, Wang C-C. Characteristics and etiologies of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients without cirrhosis: When East meets West. PLoS One 2021; 16(1):e0244939. [CrossRef]

- Santambrogio R, Opocher E, Costa M, Barabino M, Zuin M, Bertolini E et al. Hepatic resection for "BCLC stage A" hepatocellular carcinoma. The prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19(2):426–34.

- Nomura F, Ohnishi K, Tanabe Y. Clinical features and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with reference to serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. Analysis of 606 patients. Cancer 1989; 64(8):1700–7.

- Muscari F, Maulat C. Preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): is this 50-year biomarker still up-to-date? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5:46.

- Huang DQ, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 18(4):223–38. [CrossRef]

- Stine JG, Wentworth BJ, Zimmet A, Rinella ME, Loomba R, Caldwell SH et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48(7):696–703. [CrossRef]

- Desai A, Sandhu S, Lai J-P, Sandhu DS. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: A comprehensive review. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(1):1–18. [CrossRef]

- Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129(1):113–21. [CrossRef]

- Kimura T, Tanaka N, Fujimori N, Sugiura A, Yamazaki T, Joshita S et al. Mild drinking habit is a risk factor for hepatocarcinogenesis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(13):1440–50. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Kang D, Cao W, Wang Y, Liu Z. Diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012; 28(2):109–22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).