Introduction

Mongolia is an Asian country between Russia in the north and China in the south. It is a unique country with 566,460 square kilometres and a population of 3.4 million, making it the most sparsely populated country. In 2022, the GDP was US

$ 4,242 per capita, ranking 111 in the world.[

1]

As of 2023, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) records approximately 905,677 new cases and 830,180 deaths worldwide.[

2] Elevated age-standardised incidence rates (ASIR) and age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR) are mostly reported in Asian and Sub-Saharan African regions.[

2] Mongolia is endemic to HCC exhibiting the highest rates for both ASIR at 85.6 per 100,000 individuals and ASMR with 80.6 per 100,000 individuals.[

3]

The most common risk factors for HCC in Mongolia include viral hepatitis B (HBV), C (HCV) and alcohol consumption.[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]

The National Cancer Centre of Mongolia (NCCM) stands as the premier public tertiary hospital in the country, specializing in comprehensive cancer diagnosis, treatment, and management, serving as the foremost authority in oncology care nationwide.

Within the NCCM, the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery Department excels in the specialized treatment of cancers affecting the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. The department follows clinical guidelines[

12] based on the North American National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)[

13] for diagnosing and managing HCC. Their comprehensive treatment modalities include hepatotectomy, liver transplantation, and advanced systemic therapies such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy for advanced stages of HCC.[

14]

NCCM hosts the National Cancer Registry of Mongolia (NCRM), a hospital-based registry to collect data on newly registered cancers, deaths from cancer, and cancer care nationwide.[

9,

15,

16]

While a body of work investigated the survival outcomes in patients post-surgery,[

17,

18,

19] only limited information is available from an HCC-endemic country.[

6,

20,

21] Determining the survival rates and prognostic factors in HCC patients who underwent surgical treatment in Mongolia is important.

Materials and Methods

A hospital-based retrospective study using the NCRM registry data was employed to investigate the prognosis and survival rates. There were 1100 patients diagnosed with HCC who underwent liver resection from January 2015 to December 2018. Patients with postoperative pathological diagnoses of bile duct cancer, combined cancers of other organs, uncertain cases, benign liver tumours and primary cancer metastases were excluded. Patients with no complete data were excluded from the final data analysis. All diagnoses of HCC were confirmed by histopathological tests.

Before surgery, each patient underwent biochemical analyses, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and viral hepatitis infection testing. Imaging techniques such as abdominal ultrasonography, CT, and MRI were used to assess tumour resectability. The surgeries were classified using Couinaud’s classification, with major liver resection (defined as removal of ≥4 segments) indicating major vascular invasion (MaVI), and minimal resection (defined as removal of fewer than 4 segments) indicating small vascular invasion (SVI)."

A positive resection margin was defined when microscopic findings were positive, even if gross findings were negative. The Ishak classification is a system used to assess liver fibrosis and inflammation in chronic hepatitis.

Prognostic factors included in the data analysis were sex, age, HBV, HCV, HDV, alcohol consumption, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), serum AFP, cirrhosis, the extent of liver resection, blood loss, number and size of tumors, type of operation (minor or major), invasiveness of the resection margin, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumour Nodes Metastasis (TNM) stage, and vascular invasion.

Follow-up was conducted in the outpatient department of NCCM every 3 months for the first 2 years, with a physical examination, liver function tests, levels of AFP, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography. Every 6 months, the patients underwent a CT scan and/or MRI. Recurrence was evaluated with abdominal ultrasonography or CT, and hepatic artery angiography in patients with HCC recurrence, the time was stopped at diagnosis of recurrence.

In the study, survival outcomes are presented as overall survival rates. Overall survival refers to the proportion of patients who were still alive after the treatment, regardless of whether the disease has recurred. The last date of study follow-up was 1 April 2024, totaling to 9.25 years.

Statistical Analysis

In the preliminary data analyses, all selected variables were analysed using means for continuous variables and proportions for categorical ones. We evaluated overall survival rates in patients who had undergone curative resection and were discharged from the hospital, tracking from the surgery date to recurrence (if any), study end, or death. In patients with HCC recurrence, the time was stopped at diagnosis of recurrence.

Variables were selected based on their potential link to recurrence, guided by literature and our clinical expertise. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were created for these variables, and log-rank tests were performed to determine statistical differences in bi-variate survival analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 28, with a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Independent Variables Included

Demographic factors: age, sex

Clinical factors: alcohol consumption, AST, ALT, AFP levels, cirrhosis

Surgical factors: extent of liver resection, blood loss, number and size of tumours, type of operation, invasiveness of resection margin

Pathological factors: AJCC TNM stage, vascular invasion, HBV, HCV, HDV

Dependent variables included (i) prognosis (survival rates), (ii) clinical outcomes

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (2023/3-08).

Results

Between January 2015 and December 2018, data from 980 eligible patients were included in the final analysis. The proportion of male patients was slightly more (54.8%) than the female counterparts (45.2%). The median age of patients was 60[17–85]. The average tumour size was 4.4 cm, with major resections averaging 5 cm and minor resections at 4 cm (p=0.0001) (Error! Reference source not found.). The median large tumour diameter was 22 cm (1–22), and multiple lesions were present in 15.4% of cases. Major vascular invasion was identified in only 6.3% of patients, whereas small vascular invasion was present in most patients (60.1%). Preoperative median of AFP was 23.9ng/mL (range 0-121000 ng/mL).(Error! Reference source not found.). Viral hepatitis was detected in 74.28% of patients, most being HCV infection (n=353, 36.02%).

Preoperative tumour size assessment revealed that 65.3% (n=640) of tumours were ≤5 cm, while 34.6% (n=340) were >5 cm. When applying the ISHAK classification, it was observed that almost one in five patients were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis (19.29%), indicating advanced liver scarring. In contrast, the remaining 80.7% of the patients exhibited varying degrees of liver fibrosis, reflecting different stages of liver tissue damage but not reaching the threshold of cirrhosis.(

Table 1)

Survival Analysis

The average survival time for the 980 patients who underwent liver resection surgery was 6.675 years. After the surgery, cancer recurred in approximately one-third of patients (n= 308, 31.42%). Of those patients with recurred cancer, 385 (39.2%) died. The overall survival rate was reported in 60.71% of patients by the end of follow-up(N=595).

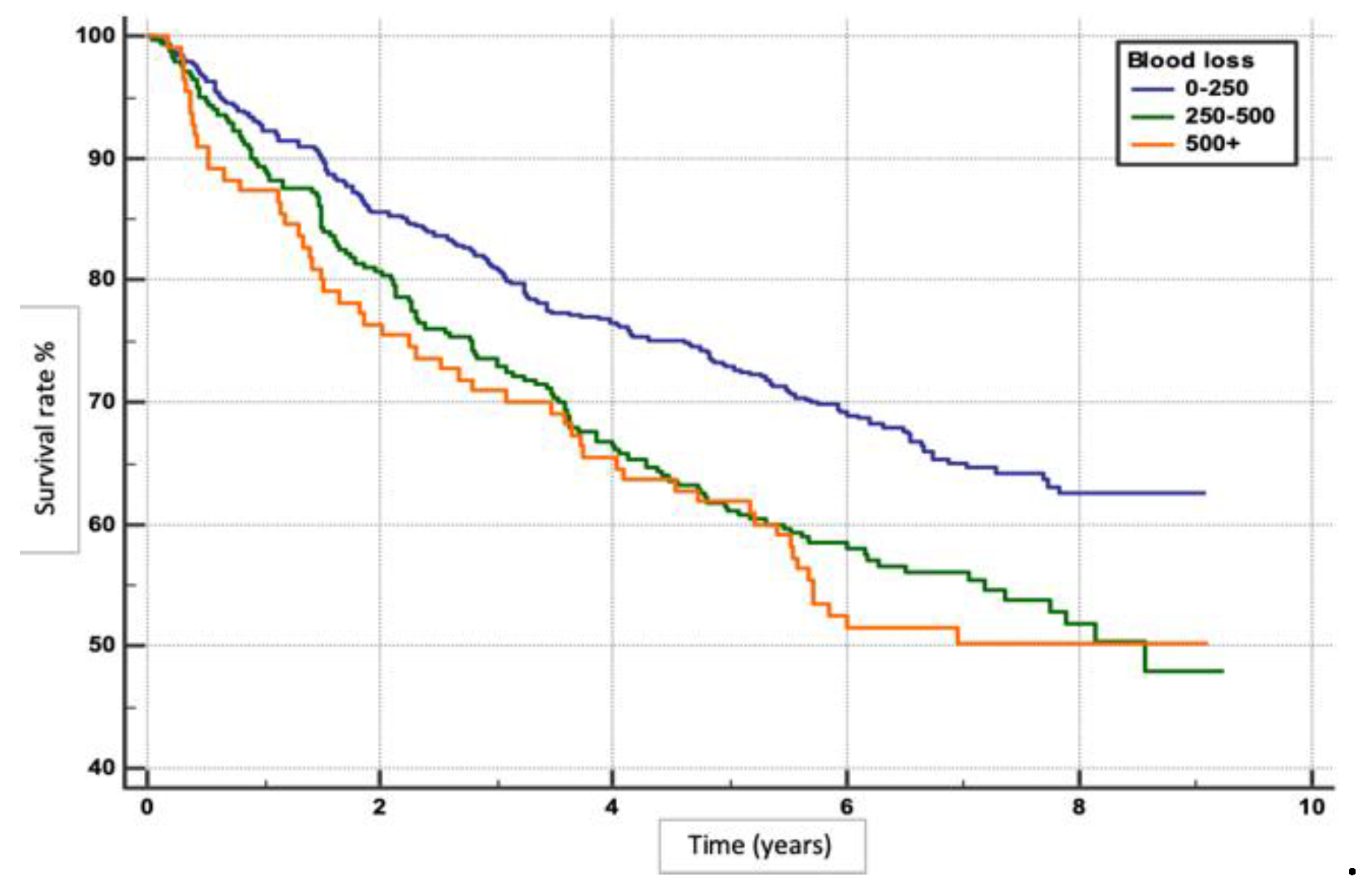

We performed an exploratory analysis to determine factors for overall survival rates in patients with HCC following hepatotectomy. Patients with minimal blood loss (0-250 ml) had the highest survival rate (p=0.0004), (

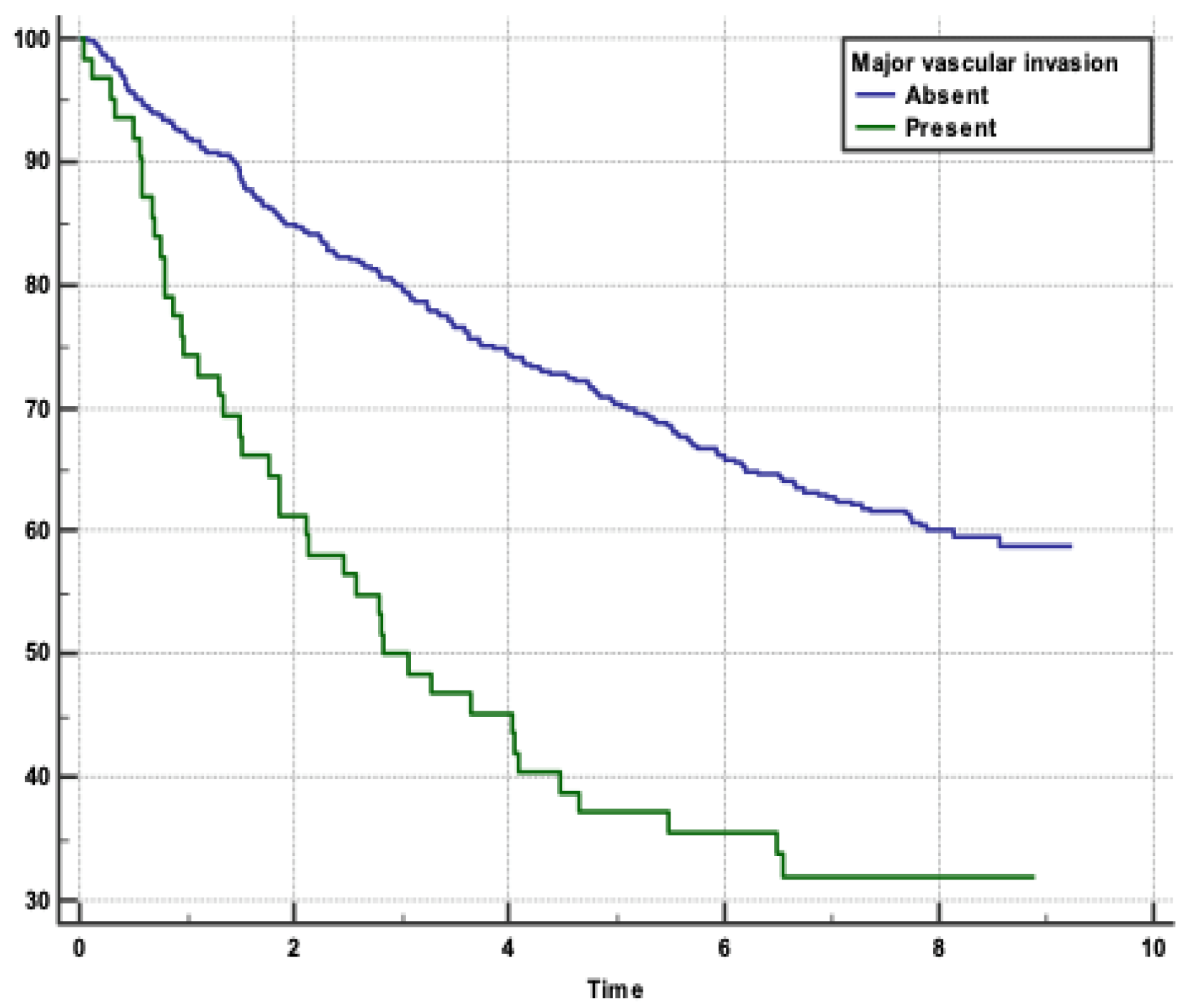

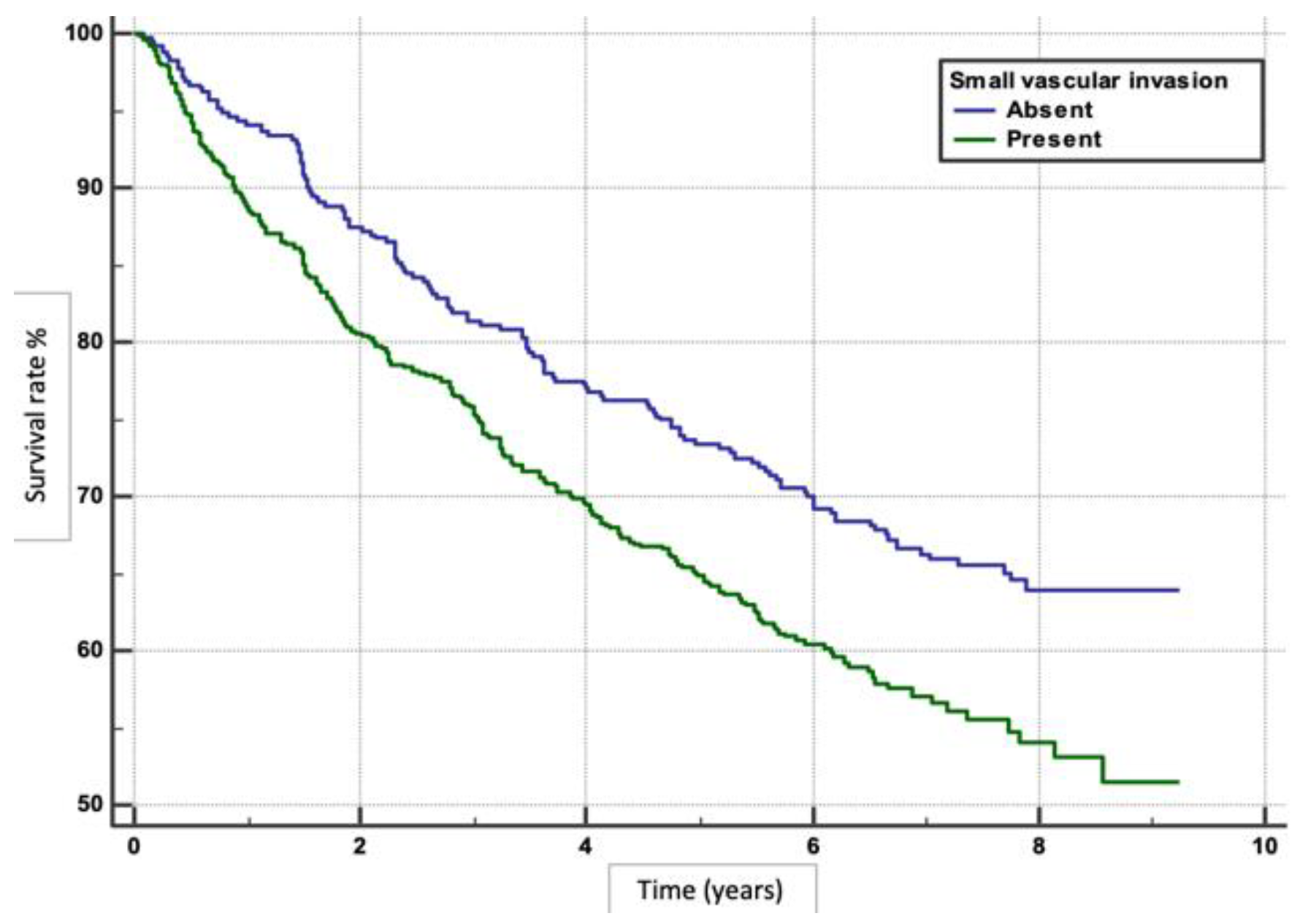

Figure 1). Absence of MaVI and SVI correlated with higher survival rates (p<0.0001, p=0.0011), respectively (

Figure 2 and

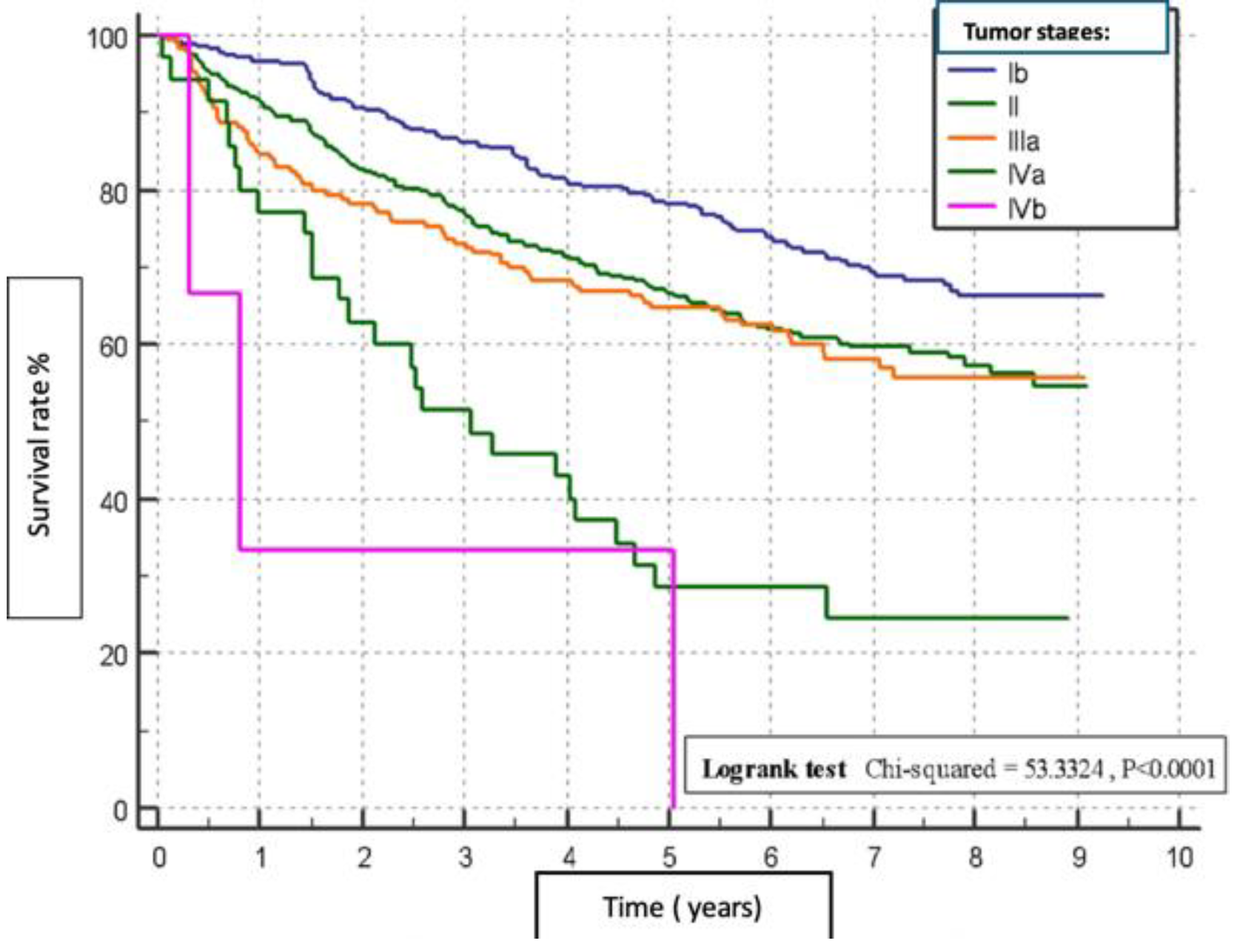

Figure 3). Tumour stage II patients had the highest survival rate (46.55%), and those with stage IIIb had the lowest (1.51%) (p=0.0001) (

Figure 4). Smaller tumours (≤5 cm) were associated with better survival (p=0.0006) (

Figure 5).(

Error! Reference source not found.).

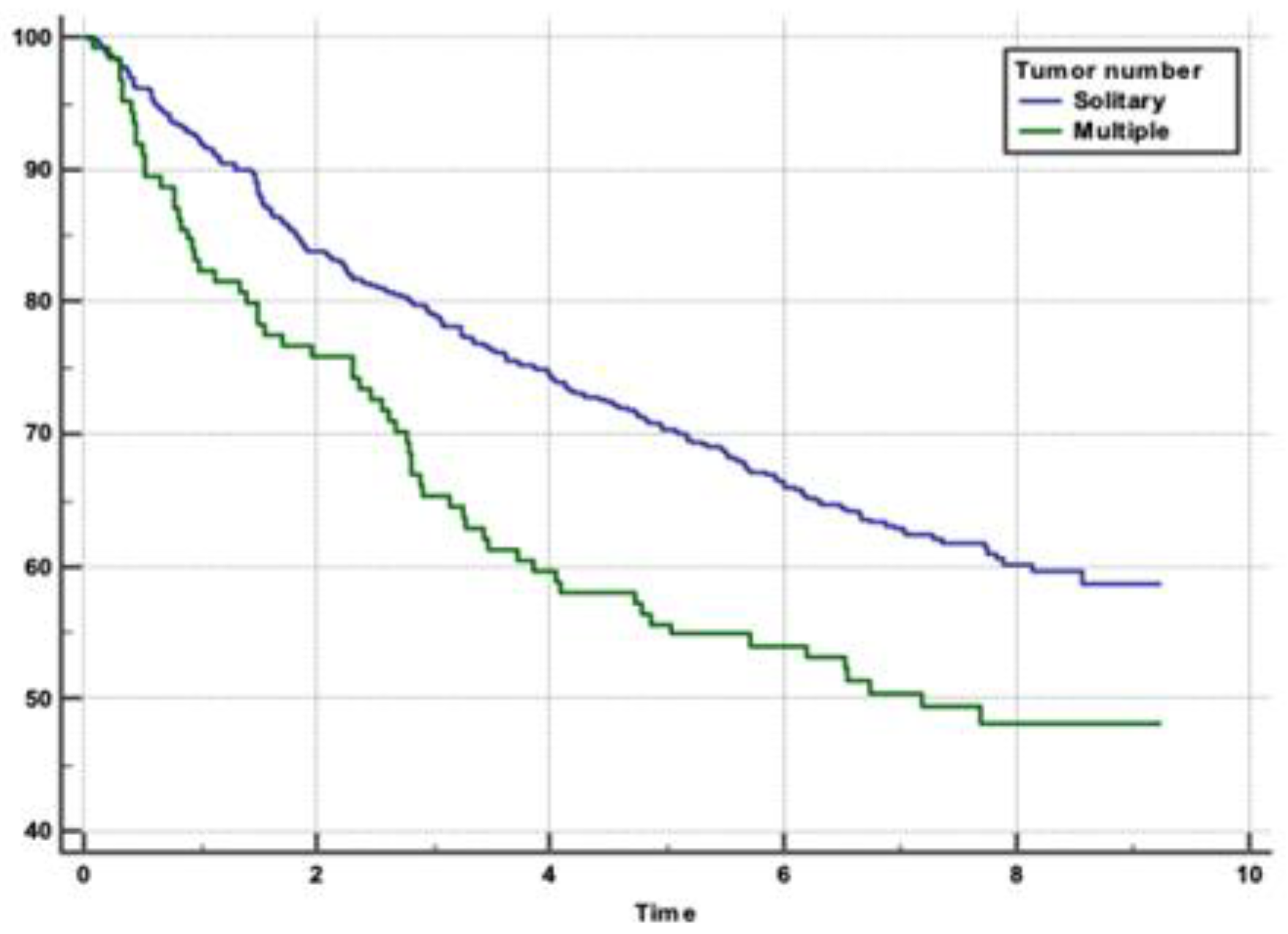

In the study, several factors were found to be independently associated with the survival outcome following hepatectomy. These factors included volume of blood loss, presence of MaVI and SVI, size and number of tumours, and levels of ALT and AST. The results indicate that higher volumes of blood loss were associated with poorer survival outcomes, with HR of 1.4535 for 250-500ml and 1.5831 for >500ml compared to 0-250ml. The presence of MaVI and SVI significantly increased the risk of mortality, with HRs of 2.5398 and 1.4145, respectively. Patients with multiple tumours had a higher risk of death compared to those with a solitary tumour (HR 1.4978), and larger tumours (>5cm) were associated with worse survival compared to smaller tumours (≤5cm) (HR 1.4325). Elevated levels of ALT and AST were also linked to poorer survival outcomes. For ALT, HRs were 1.5747 for 50-100 and 1.4173 for >100 compared to 0-50. Similarly, for AST, HRs were 1.2985 for 50-100 and 1.6576 for >100 compared to 0-50. (

Table 3)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating survival outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with HCC undergoing hepatectomy in a country endemic to HCC. In our study, the average survival time for the 980 patients who underwent liver resection was 6.675 years. Post-surgery, cancer recurred in about one-third of the patients (31.42%, n=308), and 39.2% (n=385) of those with recurrence died. By the end of the follow-up, 595 patients were survived. The findings highlight several critical factors influencing patient outcomes, particularly focusing on blood loss, vascular invasion, tumour characteristics, and liver function markers.

Blood Loss and Survival Outcomes

The volume of intraoperative blood loss was found to be a critical determinant of survival outcomes. In our study, patients experiencing greater blood loss (250-500ml and >500ml) were at up to 58% higher risk of dying compared to those with minimal blood loss (0-250ml). This finding aligns with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of minimizing blood loss during hepatectomy to improve postoperative outcomes.[

22] A US study analysed 1,803 consecutive hepatic resection cases over 10 years.[

23] In this study, the median blood loss was 600 mL and 49% of patients required transfusions. Blood loss significantly predicted survival outcomes, raising perioperative mortality risk by 69%.[

23]

Vascular Invasion

Literature findings demonstrate that the presence of vascular invasions were associated with decreased survival. In our study, the absence of SVI correlated with better outcomes (HR 1.4145) than in those with SVI. A systematic review analysed data from 37 studies enrolling 14,096 patients and reported the impact of postoperative complications on long-term survival outcomes.[

24] The HR for overall survival in patients with SVI was 1.34 (95% CI: 1.19–1.51), indicating that the presence of SVI increases the risk of mortality by 34% compared to those without SVI.[

24] The effect of SVI on the post-operative long-term prognosis was reported in a subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 eligible studies with 3033 patients.[

25] This review focused on studies reporting solitary small HCCs with maximum tumour diameters of up to 2 cm, 3 cm, or 5 cm.[

25] Similar to our findings, The meta-analysis found that the presence of SVI was associated with significantly worse overall survival (HR 2.42, 95% CI: 1.96–2.99, p<0.001).[

25]

On the other hand, some findings demonstrate that SVI has robust predictive value for survival in HCC patients following surgery. A study by Zhang et al. analyzed data from 300 patients with HCC, using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models to compare the prognostic significance of SVI and tumour size. They found that tumour size was a significant predictor of survival (HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.8-3.5, p < 0.001), while SVI was not independently significant (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9-1.6, p = 0.15). The study validated these findings using internal and external patient cohorts and statistical techniques, confirming that tumour size, rather than SVI, better predicts survival outcomes in HCC patients.[

26] This suggests that while SVI may indicate aggressive tumour characteristics, it does not independently affect overall survival rates as strongly as tumour size does.[

26]

In our study, patients without MaVI had a significantly higher survival rate compared to those with MaVI, as indicated by a HR of 2.5398. This finding underscores the critical impact of vascular invasion on the prognosis of patients with HCC. The presence of tumour thrombi in major blood vessels, such as the portal vein, is associated with a poor prognosis and high recurrence rates.[

27,

28] Vascular invasion facilitates the dissemination of cancer cells, leading to metastasis and recurrence, which significantly compromises patient outcomes. Our results align with existing literature, which consistently demonstrates that major vascular invasion is a key determinant of survival in HCC patients.[

29]

The HR of 2.5398 indicates that patients with MaVI have more than twice the risk of mortality compared to those without MaVI. Similar findings were reported from a study conducted at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, which enrolled 2,654 patients. About one-third of the patients had MaVI. The study employed Cox proportional hazards models to identify risk factors associated with decreased survival in HCC patients. Among the significant predictors identified in the study, the presence of MaVI was associated with decreased survival. The HR for MaVI was 1.599 in the curative treatment group and 1.804 in the noncurative group. This indicates that MaVI significantly increases the risk of mortality in both groups.[

30]

Our findings suggest that treatment plans for HCC should prioritize the assessment of vascular invasion. Patients without MaVI may benefit from more aggressive surgical approaches and adjuvant therapies, given their relatively better prognosis. Conversely, for patients with MaVI, a multidisciplinary approach that includes systemic therapies, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), in combination with locoregional treatments, may be recommended.[

27,

28]

Tumor Characteristics

Tumor size and number were also significant predictors of survival. In our study, smaller tumours (≤5 cm) were associated with better survival outcomes compared to larger tumours (>5 cm), with an HR of 1.4325. Additionally, patients with solitary tumours had better survival rates than those with multiple tumours (HR 1.4978). Multiple tumours often indicate a more advanced stage of disease and a higher likelihood of intrahepatic metastasis, which complicates treatment and reduces the chances of achieving complete remission.

Tumour size is one of the first five significant predictors of survival in HCC.[

26,

31,

32,

33] The systematic review analysed 72 studies involving 23,968 patients with HCC. It identified tumour size as one of the most robust predictors of death, with larger tumours significantly associated with poorer survival outcomes (HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5-2.2, p < 0.001).[

33] This can be attributed to smaller tumours being less likely to have invaded major blood vessels or metastasized, making them more amenable to curative treatments such as surgical resection or local ablation.

Liver Function Markers

Monitoring liver enzymes and biomarkers is crucial for assessing liver function and predicting surgical outcomes in HCC patients undergoing resection. In our study, elevated levels of ALT and AST were linked to poorer survival outcomes. For ALT, the HRs were 1.5747 for 50-100 U/L and 1.4173 for >100 U/L compared to the 0-50 U/L group. Similarly, for AST, the HRs were 1.2985 for 50-100 U/L and 1.6576 for >100 U/L. Similar findings can be found in the literature. [

34,

35] A study involved 601 Chinese patients with HCC who underwent hepatectomy.[

34] It used retrospective analysis to identify prognostic factors affecting overall survival. Key findings indicated that elevated preoperative ALT levels (>40 U/L) and AST levels (>35 U/L) were significantly associated with poorer overall survival (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10-1.73, p = 0.005).[

34]

Age and Gender

In our study, age and gender were not significantly associated with survival outcomes post hepatectomy. The impact of age and gender on survival rates following hepatectomy is debatable in the literature. A study analyzed 1,547 HCC patients from two European cohorts (University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland, and General Hospital Vienna, Austria). Using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression models, it found no significant difference in OS between males and females (HR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.89-1.17, p = 0.76). Age influenced OS, particularly for those aged 60-65 (HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05-1.48, p = 0.01), but after adjusting for treatment factors, the effect of age on survival was no longer significant (HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.92-1.31, p = 0.30).[

36] Nevola et al provided a comprehensive review of existing literature and clinical data to analyze the influence of gender on HCC development and outcomes[

37]. Key findings indicated that men have a higher incidence of HCC and tend to develop it at a younger age compared to women. The study highlighted that male gender was associated with a higher risk of aggressive HCC (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.10-1.65, p < 0.01), while female patients had better overall survival rates (HR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.75-0.97, p = 0.02).[

37] These findings suggest that while age and gender may not always significantly impact survival outcomes post-hepatectomy, patient characteristics, including comorbidities and lifestyle factors, play a crucial role in influencing the survival and should be carefully considered in clinical decision-making.

Limitation

Despite our efforts, this study is not without limitations. The retrospective design may introduce selection bias and limit our ability to establish causality. Additionally, data from a single center in Mongolia may not be generalizable to other countries. However, it is important to note that the National Cancer Centre of Mongolia is the sole institution providing comprehensive cancer care in the country. Furthermore, we utilised the largest and single hospital-based data encompassing all registered cancers, cancer-related deaths, and cancer care, which enhances the robustness of our findings from the HCC-endemic region.

Conclusion

The study's findings highlight the critical role of minimizing blood loss, assessing and managing vascular invasion, and monitoring tumour characteristics and liver function markers in improving survival outcomes in patients undergoing liver resection surgery. These insights can guide clinical practice and inform strategies to enhance patient care and prognosis. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and develop targeted interventions to enhance survival in this patient population.

Abbreviation

AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein.

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

ASIR: Age-standardised incidence rates.

ASMR: Age-standardised mortality rates.

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase.

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

HDV: Hepatitis D virus.

HR: Hazard Ratio.

NCCM: National Cancer Centre of Mongolia.

NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

NCRM: National Cancer Registry of Mongolia.

OS: Overall survival.

PIVKA-II: Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II.

SVI: Small vascular invasion.

TNM: Tumour Nodes Metastasis.

Author Contributions

Associate Professor Gantuya Dorj, as principal investigator, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Gurbadam, Dorj, Otgongerel, Ganbat, Demchig. Acquisition: analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Dorj, Gurbadam, Otgongerel. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Dorj, Khuyagaa, Gurbadam, Otgongerel. Administrative: technical, or material support: Dorj, Otgongerel, Khuyagaa. Supervision: Dorj.

Data availability statement

Deidentified data can be accessed via email to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The study team would like to extend their heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Gereltuya Dorj from the Quality Use of Medicines and Research Centre, University of South Australia. Her unwavering support and invaluable expertise have been instrumental to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- The National Statistical Office of Mongolia. Gross Domestic Product in 2022 2022. Available online: https://www.1212.mn/en/dissemination/56475806.

- McGlynn, K.A.; Petrick, J.L.; London, W.T. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clinics in liver disease 2015, 19, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data repository 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en.

- Alcorn, T. Mongolia's struggle with liver cancer. The Lancet 2011, 377, 1139–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazag, A.; Puntsagdulam, N.; Chinburen, J. Status quo of chronic liver diseases, including hepatocellular carcinoma, in Mongolia. The Korean journal of internal medicine 2012, 27, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baatarkhuu, O.; Kim, D.Y.; Nymadawa, P.; Kim, S.U.; Han, K.-H.; Amarsanaa, J.; et al. Clinical features and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in Mongolia: a multicentre study. Hepatology international 2012, 6, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatarkhuu, O.; Kim, D.Y.; Bat-Ireedui, P.; Han, K.-H. Current situation of hepatocellular carcinoma in Mongolia. Oncology 2011, 81 (Suppl. S1), 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondog, B.; Lise, M.; Dondov, O.; Baldandorj, B.; Franceschi, S. Hepatitis B and C virus infections in hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis in Mongolia. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2011, 20, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandagdorj, T.; Sanjaajamts, E.; Tudev, U.; Oyunchimeg, D.; Ochir, C.; Roder, D. Cancer incidence and mortality in Mongolia-national registry data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010, 11, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Oyunsuren, T.; Kurbanov, F.; Tanaka, Y.; Elkady, A.; Sanduijav, R.; Khajidsuren, O.; et al. High frequency of hepatocellular carcinoma in Mongolia; association with mono-, or co-infection with hepatitis C, B, and delta viruses. Journal of medical virology 2006, 78, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyunsuren, T.; Sanduijav, R.; Davaadorj, D.; Nansalmaa, D. Hepatocellular carcinoma and its early detection by AFP testing in Mongolia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2006, 7, 460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Mongolia. Guide for treatment of liver cancer 2016. Available online: https://moh.gov.mn/uploads/files/aceb17109da0851bcba2343f193443d5.pdf.

- Benson, A.B.; D’Angelica, M.I.; Abbott, D.E.; Anaya, D.A.; Anders, R.; Are, C.; et al. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2021, 19, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Marrero, J.A.; Rudolph, L.; Reddy, K.R. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed, T.; Sandagdorj, T.; Znaor, A.; Laversanne, M.; Tseveen, B.; Genden, P.; et al. Cancer incidence and cancer control in M ongolia: Results from the N ational C ancer R egistry 2008–12. International journal of cancer 2017, 140, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorzhgotov, B. Risk factors in the manifestations of the 5 principal forms of cancer in the People's Republic of Mongolia. La Sante Publique 1989, 32, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yilma, M.; Xu, R.H.; Saxena, V.; Muzzin, M.; Tucker, L.-Y.; Lee, J.; et al. Survival Outcomes Among Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Large Integrated US Health System. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2435066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon-Martinez, E.; Landazuri-Navas, S.; Vilchez, E.; Cantu-Hernandez, R.; Mosquera-Moscoso, J.; Encalada, S.; et al. Prognostic scores and survival rates by etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 2023, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-C.; Lee, P.-H.; Lo, G.-H.; Hsu, C.-C.; et al. Significant predictors of overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0202650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TSERENDORJ, D.; UNENBAT, G.; AMGALANTUUL, B. 10-year-survival with repeated liver resections and locoregional therapies of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery 2023, 27, S299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renchindorj, E.; Khongorzul, A.; Anujin, B.; Saruul, T.; Javkhlan, B.; Batkhishig, G.; et al. Liver cancer in Mongolia. A systematic review of current situation and its management. Journal of Asian Medical Student Association 2014, 3, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- She, W.H.; Tsang, S.H.Y.; Dai, W.C.; Chan, A.C.Y.; Lo, C.M.; Cheung, T.T. Stage-by-stage analysis of the effect of blood transfusion on survival after curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma—a retrospective study. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery 2024, 409, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarnagin, W.R.; Gonen, M.; Fong, Y.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Ben-Porat, L.; Little, S.; et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Annals of surgery 2002, 236, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Li, G.; Chai, J.; Yu, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Impact of postoperative complications on long-term survival after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgical oncology. 2021, 28, 8221–8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-H.; Zhang, X.-P.; Wang, H.; Chai, Z.-T.; Sun, J.-X.; Guo, W.-X.; et al. Effect of microvascular invasion on the postoperative long-term prognosis of solitary small HCC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 2019, 21, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Love, T.; Hao, Y.; Liu, B.L.; Thung, S.; Fiel, M.I.; et al. Tumor size, not small vessel invasion, predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2022, 158, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, T.; Tani, J.; Morishita, A.; Fujita, K.; Masaki, T.; Kobara, H. The treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion. Cancers 2024, 16, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad, A.A.; Singal, A.G.; Marrero, J.A.; Zhu, H.; Yopp, A.C. Vascular invasion and metastasis is predictive of outcome in barcelona clinic liver cancer stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2017, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Wen, Z. Survival improvement and prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of the SEER database. BMC cancer 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-H.; Hsia, C.-Y.; Chiou, Y.-Y.; Su, C.-W.; et al. Vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: prevalence, determinants and prognostic impact. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 2014, 48, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehta, A.; Elsabbagh, A.M.; Medhat, M.; Farouk, A.; Monier, A.; Said, R.; et al. Impact of tumor size on the outcomes of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. BMC surgery 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, T.-J.; Chau, G.-Y.; Lui, W.-Y.; Tsay, S.-H.; King, K.-L.; Loong, C.-C.; et al. Clinical significance of microscopic tumor venous invasion in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2000, 127, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, P.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver International 2009, 29, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Mao, Z.; Bai, L. Factors affecting the recurrence and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: a retrospective study of 601 Chinese patients. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2016, 18, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarao, K.; Rino, Y.; Takemiya, S.; Ohkawa, S.; Sugimasa, Y.; Miyakawa, K.; et al. Serum alanine aminotransferase levels and survival after hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C virus-associated liver cirrhosis. Cancer science 2003, 94, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, I.P.; Scheiner, B.; Schropp, J.; Delgado, M.G.; Schwacha-Eipper, B.; Jin, C.; et al. The Influence of Sex and Age on Survival in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevola, R.; Tortorella, G.; Rosato, V.; Rinaldi, L.; Imbriani, S.; Perillo, P.; et al. Gender differences in the pathogenesis and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biology 2023, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).