Introduction

Liver resection, also known as hepatectomy, is a surgical procedure that involves the removal of a portion or the entire liver. It is commonly performed to manage various hepatic malignancies and benign liver diseases. Hepatectomy is the primary curative option for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), metastatic liver tumors, and other localized hepatic lesions(1,2). Depending on the extent of liver involvement, liver resection can be classified into minor and major resections. Minor hepatectomies involve the removal of fewer than three Couinaud segments, while major resections involve three or more segments (sectionectomy and sectorectomy), right and left hepatectomy, extended right and left hepatectomy (3). Additionally, liver resection techniques have evolved from open laparotomy(OLS) to minimally invasive liverresection (MILR) approaches, including laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) and robotic liver resection (RLR) (4–6). These advancements have made it possible to perform complex resections with reduced postoperative morbidity (7–10).

The decision to perform liver resection depends on several factors, including the patient’s liver function, tumor location, and size, as well as the presence of extrahepatic disease. Preoperative evaluation using imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a crucial role in surgical planning (11). Despite advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative care, liver resection remains associated with significant risks, including post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF), bile leakage, intra-abdominal abscesses, and thrombotic events. Among these, PHLF is one of the most severe complications and a significant cause of postoperative mortality. It is defined by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) as impaired liver function following resection, leading to jaundice, coagulopathy, and encephalopathy (12).

Indications for liver resection varies which includes neoplasms (both malignant and benign type) and trauma. Studies have shown that malignancy is the most common indication for most of the liver resection. The liver being the most common site of metastasis, liver resection is also done for secondary liver malignancies, the most common are the metastatic colorectal tumours(8,13). Benign conditions such as simple cysts, hepatic haemangiomas, hepatic adenomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, bacterial liver abscesses, amoebic liver abscesses mostly can be treated conservatively without the need for surgery however when they are complicated there may be a need for liver resection. Intrahepatic stone accompanied by biliary strictures may also require liver resection(14). Traumatic liver injuries are mostly treated conservatively; however surgical management may be required depending on the grade of the injury. In high-grade injury cases liver resection may be useful as a treatment modality(15).

There are various complications associated with liver resection. Post hepatectomy liver failure and post hepatectomy renal failure are the most severe complications of liver resection. Other complications include bile leak, pulmonary complication, ascites, thrombotic complications, intraoperative and postoperative bleeding, surgical site infections and pain. It has been shown that LLR has reduced severity of complications as compared to OLR(16–18).

In high-income countries, liver resection outcomes have improved substantially due to better patient selection, advanced surgical techniques, and improved perioperative care. Reported postoperative mortality rates in specialized centers range between 1% and 5% (19). However, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including sub-Saharan Africa, liver resections performed less frequently. Limited access to specialized surgical expertise, delayed presentation, and inadequate perioperative support contribute to higher complication rates and poorer outcomes (20). Studies from LMICs emphasize the need for capacity building and infrastructure development to improve liver surgery outcomes (21).

Liver resection remains a mainstay curative treatment for patients with various liver conditions including liver cancer, benign tumours and hepatic metastasis. Globally there has been great improvement in liver resection, progress in preoperative assessment and refinement if surgical techniques are accounted for dramatic improved safety and prognostic outcomes in liver surgery. Studies have shown that the application of detailed preoperative assessment and intraoperative procedures to minimize blood loss is attributed to most of the successful liver resection(22).

Despite the improvement, Studies have shown that with the sophisticated technologies that have developed over the past few decades there have been improvement of the outcomes of liver resection. However, there are still many severe short-term and long-term complication associated with liver resection, and the morbidity associated with these surgeries is still high(23).

This study focuses on factors influencing the outcomes of liver resections at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital, Dodoma, Tanzania. The hospital serves as a referral center for the central zone of Tanzania, where liver resections are increasingly being performed. The objectives of this study are to describe the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing liver resection, evaluate surgical outcomes, and identify key factors influencing these outcomes. Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing surgical care and reducing morbidity and mortality associated with liver surgery in resource-limited settings.

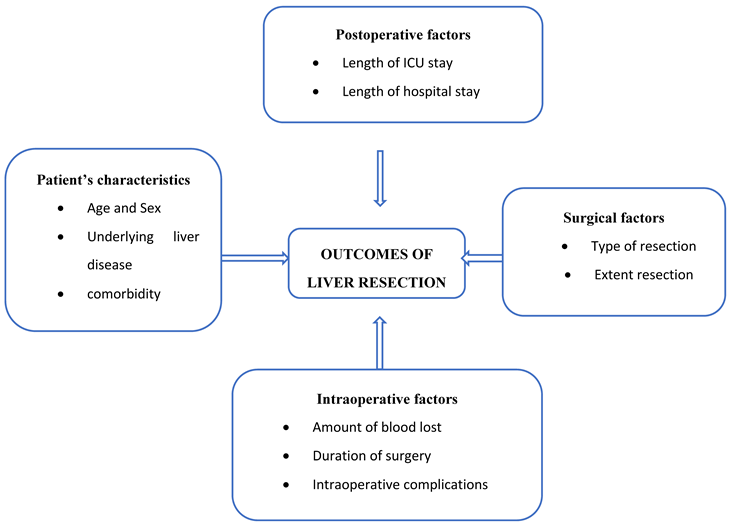

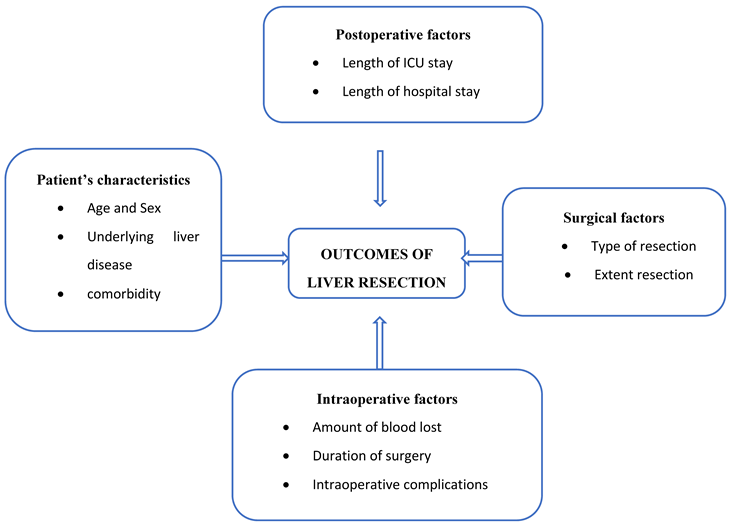

Conceptual Frame Work

Various factors influence the outcome of liver resection. Patients characteristics such age sex, comorbidities, performance status, intraoperative factors such as amount of blood lost and intraoperative complications, surgical factors such as the type and extent of resection, and postoperative factors such as ICU admission, Length of hospital stay.

Literature Riview

Clinical characteristics such as presenting symptoms, the duration of symptoms, hepatitis status (hepatitis B, C), comorbidities, ECOG performance status, Child Pugh score, BCLC stage, brings about the variation in the outcomes of the study(4).

Outcomes of liver resection.

Post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) is one of the most severe complications of liver resection. Post hepatectomy liver failure is defined as the impaired ability of the liver to maintain it’s synthetic, excretory, and detoxifying functions, which are characterised by an increased international normalized ratio and concomitant hyperbilirubinemia on or postoperative day 5 (24). A study conducted in USA showed that the main risk factors for PHLF were underlying functional liver disease and an insufficient volume of the residual liver remnant(25,26).

Postoperative acute renal failure is one of the outcomes of liver resection. Postoperative ARF is defined according to the RIFLE criteria as an absolute increase in serum-creatinine of more than 0.3 mg/dl above baseline, or an increase of more than 1.5 times the preoperative baseline value within 48 hours after surgery, or a reduction of urinary output less than 0.5 ml/kg/h for at least 6 h(27) The reported incidence of AKI ranges from 3 to 21.6 per cent in the literature, wide variation is attributed to non-standardized definition of AKI and partly because different patient populations were studied, studies have shown that Postoperative acute renal failure following liver resection is associated with increased length of ICU admission, increased length of hospital stay, morbidity and mortality.

Perihepatic resection mortality rate is high, even in the high-volume centres which occurs as the result of intraoperative complications or postoperative complications. Another study conducted in Germany showed that with a mortality rate was between 5.8% to 10.4% depending on the type and extent of resection. PHLF is also one of the causes of mortality following liver resection, mortality associated with PHLF was as ahigh as 70% (25,26,28,29).

The outcome profile is the developing countries is not very different from that observed in the developed countries. A study done in south Africa showed that there were no postoperative deaths, and 7 of the 22 patients who were included in the study had postoperative complications such as subphrenic abscess, bile leak, and pleural effusion. Another study conducted in Morocco showed that 14.3% of the participants had severe complications including mortality rate of 4.8%(30,31).

Factors influencing outcomes of liver resection.

factors such as the underlying liver disease, performance status, Laboratory investigations such as Liver function tests, Type of liver resection and the extent of resection, amount of blood lost, length of hospital stay are some of the factors influencing outcomes of liver resection(8). Furthermore, the hospital procedural volume has an impact on the outcomes of liver resection, it has been shown that hospitals with high procedural volume have a better outcome as compared to those with low procedural volume(22). The type of liver resection that the patient has undergone is associated to the severity of the complications, a study done in France showed that patients who underwent anatomical liver resection had less severe complications as compared to the patients who had underwent non anatomical liver resection(32). patients with cirrhosis have a greater risk of complications as compared to patients with no cirrhosis. Also, complications are seen in patients who have underwent extended hepatectomies in which a large portion of the liver is removed(13–15).

However, in developing countries Liver resection is seldom done. In most of the sub-Saharan African countries, liver resection is a new practice and it’s done in fewer patients as compared to the developed countries. Late diagnosis of the liver diseases due to lack of surveillance rendering it impossible to do liver resection as a curative treatment, limited resources are some of the reasons(33).

Methods and Materials

Study Design

A retrospective cross-sectional study design was conducted at Benjamini Mkapa Hospital Dodoma, Tanzania.

Study Area

This study was conducted at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital (BMH), located in Dodoma, Tanzania. BMH is a referral hospital established in 2015 and serves as one of the leading healthcare institutions in Tanzania. The hospital has advanced medical technology, well-trained healthcare professionals, and comprehensive inpatient and outpatient services. It serves as a teaching and research facility affiliated with the University of Dodoma (UDOM), making it an ideal location for conducting clinical and health-related research. The choice of BMH as the study area is informed by its central geographical location, diverse patient population, and its reputation for handling complex cases, including specialized surgeries.The facility provides specialized medical services, including surgical interventions, cardiology, surgical and medical gastroenterology/hepatology unit, a pathology unit, an oncology unit, and an interventional/diagnostic radiology unit capable of providing tertiary-level healthcare services to patients undergoing liver resection.

Study Population

All the patients who underwent liver resection due to various reasons at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital from January 2020 to October 2023.

Sampling Technique

This study was use consecutive sampling technique where by all patients who underwent liver resection at BMH was selected.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All the patient who underwent liver resection at Benjamini Mkapa Hospital were included in the study and all the patients with incomplete clinical information were excluded in the study.

Variables

Dependent variable on outcomes of liver resection includes, liver failure, PHRF, mortality, bile leak, pulmonary complications such as pleural effusion and pneumonia, surgical site infection, bleeding and others. Also the independent variables were socio-demographics such as age, sex and comorbidities, Underlying liver disease such as infection with hepatitis B, C, Liver cirrhosis, primary benign or malignant tumours of the liver and metastatic tumours of the liver, presenting symptoms and duration of the presenting symptoms, Performance status, the Eastern cooperative oncology group (ECOG), CHILD-Pugh status and Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) staging, Laboratory investigations such as Full blood picture (FBP) ,haemoglobin (Hb), Platelets, Liver function test (LFT) Prothrombin time (PT), Partial thromboplastin time (PTT), International normalized ratio (INR), Direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, total bilirubin, Albumin, Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), Alkaline phosphate (ALP), Gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), renal function test such creatinine and Blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Type of liver resection such as wedge resection, segmental resection (sectionectomy and sectorectomy), right and left hepatectomy, extended right and left hepatectomy, major hepatectomy or minor hepatectomy. This includes estimated amount of blood lost intraoperatively, Length of ICU stay, Length of hospital stay

Data Collection

Demographic and clinical data were obtained from hospital records, including the patient’s personal information (age and gender), the indication for liver resection, and any comorbidities. Preoperative assessment results were retrieved from the Jeeva system, while intraoperative notes and postoperative notes, including ICU records, were obtained from the patients’ files. After data collection, the data were initially checked for completeness and consistency. Subsequently, the data were entered into SPSS version 25, then coded, recoded, and cleaned.

Data Processing and Analysis

After cleaning, the data were analyzed using statistical software such as SPSS. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, including mean, median, frequency, percentages, and proportions. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to determine associations between categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance for conducting this study was sought from the CREC Research ethics committee, permission to collect data was sought from the Benjamin Mkapa Hospital’s Training, Research and Consultancy Unit. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards privacy and confidentiality of the patients’ information was held, and there are no risks expected from this study and the study was done under supervision. Since the data was collected retrospectively, informed consent was waived.

Results

Socio Demographic Characteristics

The study included 18 patients who underwent liver resection at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital between January 2020 and October 2023. The majority of patients were over 50 years old (55.6%), with the remaining age groups being 18 to 35 years (27.8%) and 36 to 50 years (16.7%). Female patients predominated, accounting for 77.8% of the cohort, while 22.2% were male. The distribution of patients by residence was evenly split, with 50% residing in Dodoma and the other 50% from upcountry regions (

Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics of Patients

Regarding clinical characteristics, only 16.7% of patients reported alcohol use, and none had a history of cigarette smoking. A significant portion of the cohort (38.9%) had a history of chronic disease. Hepatitis B and C infections were relatively rare, with 5.6% and 11.1% positivity rates, respectively. HIV positive was also 5.6%. Biopsy results revealed that 61.1% of the patients had benign liver conditions, while 38.9% were diagnosed with malignant conditions (

See Table 2).

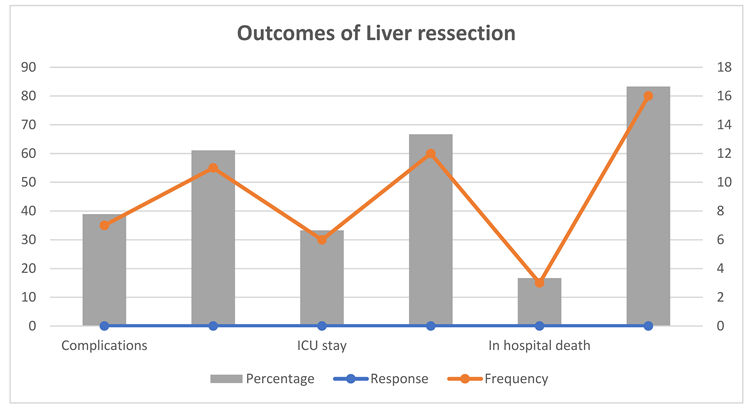

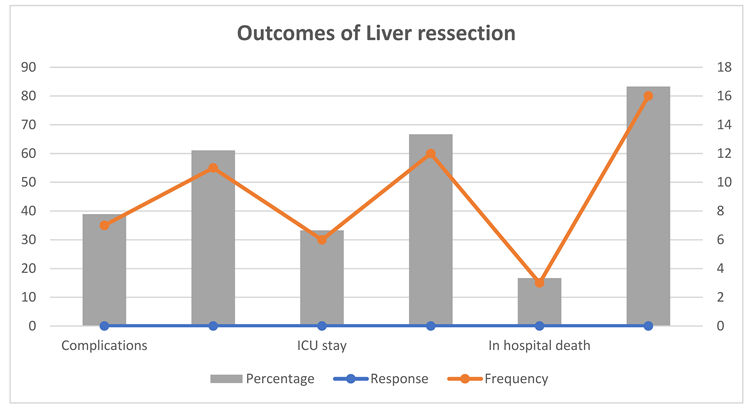

Outcomes of Liver Resection

Study shows that, about 38.9% of patients experienced postoperative complications. The need for ICU care was observed in 33.3% of the cases, with a median ICU stay of 8 days, ranging from 4 to 22 days. The in-hospital mortality rate was 16.7%. The most common complications were liver-related, affecting 27.8% of patients. Renal and respiratory complications were also noted in 16.7% and 11.1% of patients, respectively. Other complications, such as gastrointestinal, wound, cardiovascular, hematological, and metabolic issues, occurred less frequently.(

Table 3 and Figure 1)

Causes of Death

Among the 18 patients studied, the causes of death were varied. The majority, comprising 83.3% (15 patients) were alive later on and had unspecified causes of death. The remaining deaths were due to specific causes: 5.6% (1 patient) died from cardiac arrest, 5.6% (1 patient) from multi-organ dysfunction and refractory hemorrhagic shock, and 5.6% (1 patient) from severe bradycardia and hypotension. These causes account for 100% of the recorded deaths.

Table 5.

Causes of Death.

Table 5.

Causes of Death.

| Causes |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| |

Cardiac rest |

1 |

5.6 |

88.9 |

| Multi-organ dysfunction, refractory haemorrhagic shock |

1 |

5.6 |

94.4 |

| Severe bradycardia and hypotension |

1 |

5.6 |

100.0 |

Regarding the Child-Pugh classification and its relation to complications, 5 out of 16 patients in Child-Pugh Class A experienced complication, while 11 did not. In Child-Pugh Class B, both patients experienced complications. Overall, 7 out of 18 patients (38.9%) encountered complications, whereas 11 out of 18 patients (61.1%) did not.

Table 6.

Child Pugh and Complications.

Table 6.

Child Pugh and Complications.

| |

Complications |

Total |

| Yes |

No |

| Child Pugh |

Class A |

5 |

11 |

16 |

| Class B |

2 |

0 |

2 |

| Total |

7 |

11 |

18 |

Association Between Age, Biopsy Findings and Duration of Symptoms

The correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between age and biopsy findings, with a R coefficient of 0.571 (p = 0.013), indicating that older patients were more likely to have certain biopsy findings, possibly malignant ones. However, there was no significant correlation between age and the duration of symptoms (r = 0.085, p = 0.737), suggesting that age does not influence how long patients have experienced symptoms before undergoing liver resection. Similarly, the correlation between the duration of symptoms and biopsy findings was weak and non-significant (r = 0.106, p = 0.676), indicating that the length of time a patient had symptoms did not have a strong relationship with the biopsy results. These results suggest that while age may influence biopsy outcomes, the duration of symptoms does not significantly correlate with age or biopsy findings.

Table 7.

Association between Age, biopsy findings and duration of symptoms.

Table 7.

Association between Age, biopsy findings and duration of symptoms.

| Correlation |

age |

duration of symptoms |

Biopsy findings |

| age |

r |

1 |

.085 |

.571*

|

| P-value |

|

.737 |

.013 |

| N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

| Duration of symptoms |

r |

.085 |

1 |

.106 |

| P-value |

.737 |

|

.676 |

| N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

| Biopsy findings |

r |

.571*

|

.106 |

1 |

| P-value |

.013 |

.676 |

|

| N |

18 |

18 |

18 |

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). |

Correlation Between Various Factors Influencing the Outcomes of Liver Resection

The analysis of correlations between various factors influencing the outcomes of liver resection at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital revealed several key relationships. Notably, there was a significant positive correlation between age group and biopsy findings (r = 0.517, p = 0.028), indicating that older age groups were associated with specific biopsy outcomes. Additionally, the correlation between residence and hospital stay was also significant (r = 0.499, p = 0.035), suggesting that patients’ place of residence may influence the length of their hospital stay post-surgery.

Complications following liver resection were significantly correlated with biopsy findings (r = 0.561, p = 0.016) and in-hospital death (r = 0.561, p = 0.016), highlighting that the type of biopsy findings and the occurrence of complications are important predictors of mortality. Moreover, ICU stay was negatively correlated with in-hospital death (r = -0.661, p = 0.003), indicating that extended ICU stays may be associated with a higher risk of death in-hospital.These correlations suggest that age, residence, biopsy findings, and complications are significant factors influencing outcomes such as hospital stay and mortality in liver resection patients at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital.

Discussion

This study investigated the factors influencing the outcomes of liver resection at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital by analyzing socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as postoperative outcomes.

The findings reveal that the majority of patients undergoing liver resection were older than 50 years, comprising 55.6% of the cohort. This aligns with global trends where liver resection is more commonly performed in older patients due to the higher prevalence of liver-related diseases in this age group. The predominance of female patients (77.8%) is notable and contrasts with some studies that report a higher incidence of liver surgeries in males. This gender distribution could be reflective of the specific population served by Benjamin Mkapa Hospital or possibly cultural and social factors influencing healthcare-seeking behavior among women.

The equal distribution of patients between Dodoma and upcountry regions suggests that liver resection services at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital are accessible to patients from different geographical locations. However, the socio-economic implications of traveling from upcountry regions for specialized care need further exploration.

The study’s findings regarding the prevalence of lifestyle-related risk factors among patients undergoing liver resection at BMH reveal intriguing insights (34). The relatively low rates of alcohol use (16.7%) and complete absence of cigarette smoking (0%) stand out, this is an interesting finding as this factors are traditionally associated with liver diseases. The absence of a smoking history among patients is particularly noteworthy and may suggest either a genuinely low prevalence of smoking in this population or potential underreporting of smoking habits (34).

The study highlighted that about 38.9% of patients had a history of chronic diseases, aligning with known risk factors for liver conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic viral hepatitis (34). The low prevalence of Hepatitis B (5.6%) and C (11.1%) infections is noteworthy, especially given the high burden of viral hepatitis in sub-Saharan Africa. These figures hint at the possibility of other etiologies, potentially related to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), being more prevalent in this patient cohort (34).

The biopsy findings from the study reveal that benign conditions were more prevalent than malignant ones, constituting 61.1% of the cases. This prevalence of benign conditions may reflect the selection criteria for surgery at BMH, where only patients with resectable and potentially curable benign lesions or early-stage malignancies are considered for surgical intervention.

Regarding postoperative outcomes, the study revealed a significant rate of complications, with 38.9% of patients experiencing adverse events. While this complication rate falls within the range reported in other studies, it underscores the inherent risks associated with liver surgery. The high proportion of liver-related complications (27.8%) emphasizes the liver’s vulnerability to surgical stress, particularly in patients with pre-existing liver conditions.

The study highlighted that one-third of patients (33.3%) required intensive care unit (ICU) For close postoperative monitoring, it reflects the complexity of liver resections and the need for close monitoring. The median ICU stay of 8 days is consistent with the recovery trajectory for major liver surgery, although the wide range of ICU stays (4 to 22 days) suggests variability in patient responses and the severity of complications (35).

The in-hospital mortality rate of 16.7% is higher than the global average for liver resection, which typically ranges from 3% to 10%. This elevated mortality rate could be attributed to several factors, including the complexity of cases handled at BMH, the presence of comorbidities, or potentially limited resources for perioperative care. The mortality rate also emphasizes the need for careful patient selection, preoperative optimization, and possibly enhancing the perioperative care infrastructure. In German reported overall mortality rate of 5.8% (36). These events are in line with previous reports on increased mortality after liver resection with persistent derangement of bilirubin metabolism and coagulation pathway after liver resection (37).

The study identified a range of complications among patients who underwent liver resection at BMH, with liver-related complications being the most prevalent. Occurring in 27.8% of patients, liver complications are a significant concern due to the organ’s central role in metabolism and the body’s response to surgical stress. Hematological complications were the second most frequent, affecting 38.9% of patients. This high rate could be due to the extensive vascular nature of the liver, which can lead to significant blood loss and coagulopathies during and after surgery.

Renal and metabolic complications, each occurring in 16.7% of patients, further emphasize the multi-organ impact of liver surgery. The renal complications may be a result of perioperative hypo-perfusion or nephrotoxic drugs, while metabolic issues could stem from the liver’s impaired ability to maintain metabolic homeostasis post-surgery. Respiratory complications, observed in 11.1% of cases, could be related to prolonged anaesthesia, pain management, or underlying comorbid conditions.

Gastrointestinal, wound, cardiovascular, and metabolic complications were less common, each affecting 5.6% of the patients (38). While these complications were less frequent, their presence still highlights the complexity of managing patients undergoing liver resection, where even minor complications can significantly affect recovery and overall outcomes (39,40).

The study shows an in-hospital mortality rate of 16.7%, with deaths attributed to cardiac arrest, multi-organ dysfunction due to refractory haemorrhagic shock, and severe bradycardia with hypotension. These causes reflect the severe physiological challenges and complications that can arise postoperatively in patients undergoing liver resection. Cardiac arrest and severe bradycardia with hypotension may be linked to intraoperative or postoperative hemodynamic instability, possibly exacerbated by pre-existing conditions or the body’s response to the extensive surgery. In extended liver resections, a 90-day mortality rate of up to 16.7% has been reported (41). In German reported overall mortality rate of 5.8% (36). These events are in line with previous reports on increased mortality after liver resection with persistent derangement of bilirubin metabolism and coagulation pathway after liver resection (37).

The study findings on the association of Child-Pugh classification with complications in patients undergoing liver resection resonate with existing literature that highlights the impact of liver function on surgical outcomes(9). Patients classified as Child-Pugh Class B were more likely to experience complications compared to those in Class A. This finding is consistent with existing literature, which indicates that patients with poorer liver function (as reflected by a higher Child-Pugh score) are at greater risk for complications and adverse outcomes following liver surgery(42). This is similar to study done by Troisi et al. (2021) comparing laparoscopic and open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis, shedding light on the safety and feasibility of different surgical approaches in this patient population. Similarly, the study by Watanabe et al., (2022) explored the outcomes of laparoscopic liver resection for HCC in patients with Child-Pugh B7 and B8/9 cirrhosis, providing insights into surgical risks, recurrence, and survival in this specific cohort(43).

The correlation analysis revealed that age was significantly associated with biopsy findings, suggesting that older patients are more likely to have specific biopsy results, potentially indicating malignancy ((44). This finding aligns with the understanding that the risk of liver malignancies increases with age, possibly due to cumulative exposure to risk factors such as chronic hepatitis infections or fatty liver disease aligns with investigations by (Girish & Shrestha, 2020), who examined the association of Child-Pugh score with the presence of large esophageal varices in chronic liver disease patients. Additionally, the research done by Mai et al. (2022) shows the prognostic significance of serum sodium levels in liver cirrhosis, highlighting the importance of biochemical markers in assessing disease severity and predicting clinical outcomes in cirrhotic patients. The duration of symptoms is not significantly correlate with either age or biopsy findings. This lack of correlation suggests that the length of time a patient has experienced symptoms may not be a reliable indicator of the severity or type of liver pathology, which could have implications for the timing of interventions and the urgency of surgical decisions.

The study further explored correlations between various factors influencing the liver resection outcomes. Notably, there was a significant positive correlation between age group and biopsy findings, reinforcing the idea that older age is associated with specific liver pathologies (Zajic et al., 2017). Additionally, a significant correlation was found between residence and hospital stay, indicating that patients’ geographical location might influence the duration of hospitalization, possibly due to differences in access to follow-up care or the need for extended recovery time before returning home this is similar to study done which showing the relationship between the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and ICU stay underscores the importance of risk stratification tools in predicting patient outcomes (Dalal et al., 2023).

Complications were significantly correlated with biopsy findings and in-hospital death in the study underscoring the importance of biopsy results in predicting postoperative outcome (Vigouroux et al., 2021). The significant correlation between ICU stay and in-hospital death suggests that patients requiring longer ICU stays are at a higher risk of mortality, likely due to the severity of their condition or complications that arise during the postoperative period (Kawasaki, 2023; Lim, 2024). The correlation between complications, biopsy findings, and in-hospital mortality resonates with investigations by Tada in 2021, who evaluated the impact of modified albumin–bilirubin grade on survival in HCC patients receiving lenvatinib(44). This study underscored the relevance of liver function assessments in predicting treatment outcomes and survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, aligning with the significance of biopsy results and postoperative complications in the context of liver surgery.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the complexity and risks associated with liver resection at Benjamin Mkapa Hospital. The high rate of complications, particularly liver and hematological issues, highlights the need for careful patient selection and preoperative optimization. Additionally, the significant correlations between age, biopsy findings, and complications with outcomes like hospital stay and mortality suggest that these factors should be carefully considered in clinical decision-making.

Recommendation

To improve outcomes associated with liver resection, the following recommendations should be done; Fistly, Tailoring preoperative assessments to identify high-risk patients, particularly older individuals and those with poor liver function, can help mitigate the risks of complications. Secondly, strengthening postoperative care, particularly in monitoring and managing liver and hematological complications, may reduce mortality and improve recovery times. Thirdly, A multi-disciplinary approach involving hepatologists, surgeons, intensivists, and other specialists could enhance the management of complex cases, ensuring comprehensive care. Fouthly, Continued research is needed to explore the factors influencing outcomes further, including larger studies that can validate these findings and identify additional predictors of success in liver resection surgeries.

Funding

No external Source of funding.

Conflict of interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

Anatomic Liver Resection (ALR); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG); Hospital Procedural Volume (HPV); Laparoscopic Liver Resection (LLR); Liver Resection (LR); Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD); Minimal Invasive Liver Resection (MILR); Benjamin Mkapa Hospital (BMH); Non-Anatomic Liver Resection (NALR); Open Liver Resection (OLR); Post Hepatectomy Liver Failure (PHLF); and Robotic Liver Resection (RLR).

References

- Barkhatov L, Aghayan DL, Scuderi V, Cipriani F, Fretland ÅA, Kazaryan AM, et al. Long-term oncological outcomes after laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing redo liver resections for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a European multi-center study. Surg Endosc. 2022 May 1;36(5):3374–81.

- Mise Y, Sakamoto Y, Ishizawa T, Kaneko J, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, et al. A worldwide survey of the current daily practice in liver surgery. Liver Cancer. 2013 Jan;2(1):55–66.

- Schwarz C, Plass I, Fitschek F, Punzengruber A, Mittlböck M, Kampf S, et al. The value of indocyanine green clearance assessment to predict postoperative liver dysfunction in patients undergoing liver resection. Sci Rep. 2019 Jun 10;9(1):8421.

- Lee KF, Lo EYJ, Wong KKC, Fung AKY, Chong CCN, Wong J, et al. Acute kidney injury following hepatectomy and its impact on long-term survival for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BJS Open. 2021 Oct 3;5(5):zrab077.

- Gau RY, Yu MC, Tsai HI, Lee CH, Kuo T, Lee KC, et al. Laparoscopic Liver Resection Should Be a Standard Procedure for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Low or Intermediate Difficulty. J Pers Med. 2021 Apr;11(4):266.

- Aragon RJ, Solomon NL. Techniques of hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012 Mar;3(1):28–40.

- Conticchio M, Delvecchio A, Ferraro V, Stasi M, Casella A, Filippo R, et al. Standardization of robotic right liver mobilization. Int J Med Robot. 2023;19(6):e2551.

- Abreu P, Ferreira R, Bussyguin DS, DaCás E, Venkatasamy VV, Tomasich FDS, et al. Liver resections for metastasis: surgical outcomes of a single center academic institution. BMC Surg. 2020 Oct 27;20:254.

- Kokudo N, Takemura N, Ito K, Mihara F. The history of liver surgery: Achievements over the past 50 years. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020 Mar;4(2):109–17.

- Reddy SK, Barbas AS, Turley RS, Steel JL, Tsung A, Marsh JW, et al. A standard definition of major hepatectomy: resection of four or more liver segments. HPB. 2011 Jul;13(7):494–502.

- Conci S, Viganò L, Ercolani G, Gonzalez E, Ruzzenente A, Isa G, et al. Outcomes of vascular resection associated with curative intent hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Sep 1;46(9):1727–33.

- Yang HY, Rho SY, Han DH, Choi JS, Choi GH. Robotic major liver resections: Surgical outcomes compared with open major liver resections. Ann Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2021 Feb 28;25(1):8–17.

- Schmelzle M, Krenzien F, Schöning W, Pratschke J. Laparoscopic liver resection: indications, limitations, and economic aspects. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405(6):725–35.

- Oldhafer KJ, Habbel V, Horling K, Makridis G, Wagner KC. Benign Liver Tumors. Visc Med. 2020 Aug 4;36(4):292–303.

- Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Ordonez C, Kluger Y, Vega F, Moore EE, et al. Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Mar 30;15(1):24.

- Takahara T, Wakabayashi G, Beppu T, Aihara A, Hasegawa K, Gotohda N, et al. Long-term and perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with propensity score matching: a multi-institutional Japanese study. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2015 Oct;22(10):721–7.

- Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery. 2011 May;149(5):680–8.

- Yoshiya S, Shirabe K, Nakagawara H, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, Ikegami T, et al. Portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy. World J Surg. 2014 Jun;38(6):1491–7.

- Rudnicki Y, Pery R, Shawki S, Warner S, Cleary SP, Behm KT. A Synchronous Robotic Resection of Colorectal Cancer and Liver Metastases—Our Initial Experience. J Clin Med. 2023 Jan;12(9):3255.

- Sammarco A, de’Angelis N, Testini M, Memeo R. Robotic synchronous treatment of colorectal cancer and liver metastasis: state of the art. Mini-Invasive Surg. 2019 Oct 25;3(0):N/A-N/A.

- Mitsuka Y, Yamazaki S, Yoshida N, Yan M, Higaki T, Takayama T. Time interval-based indication for liver resection of metastasis from pancreatic cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2020 Nov 10;18(1):294.

- Dimick JB, Cowan JA, Knol JA, Upchurch GR. Hepatic resection in the United States: indications, outcomes, and hospital procedural volumes from a nationally representative database. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960. 2003 Feb;138(2):185–91.

- Ishii M, Mizuguchi T, Harada K, Ota S, Meguro M, Ueki T, et al. Comprehensive review of post-liver resection surgical complications and a new universal classification and grading system. World J Hepatol. 2014 Oct 27;6(10):745–51.

- Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery. 2011 May;149(5):713–24.

- Mullen JT, Ribero D, Reddy SK, Donadon M, Zorzi D, Gautam S, et al. Hepatic insufficiency and mortality in 1,059 noncirrhotic patients undergoing major hepatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 May;204(5):854–62; discussion 862-864.

- Wibmer A, Prusa AM, Nolz R, Gruenberger T, Schindl M, Ba-Ssalamah A. Liver failure after major liver resection: risk assessment by using preoperative Gadoxetic acid-enhanced 3-T MR imaging. Radiology. 2013 Dec;269(3):777–86.

- Slankamenac K, Breitenstein S, Held U, Beck-Schimmer B, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. Development and validation of a prediction score for postoperative acute renal failure following liver resection. Ann Surg. 2009 Nov;250(5):720–8.

- Filmann N, Walter D, Schadde E, Bruns C, Keck T, Lang H, et al. Mortality after liver surgery in Germany. Br J Surg. 2019 Oct;106(11):1523–9.

- Fong Y, Gonen M, Rubin D, Radzyner M, Brennan MF. Long-Term Survival Is Superior After Resection for Cancer in High-Volume Centers. Ann Surg. 2005 Oct;242(4):540–7.

- Houssaini K, Lahnaoui O, Souadka A, Majbar MA, Ghannam A, El Ahmadi B, et al. Contributing factors to severe complications after liver resection: an aggregate root cause analysis in 105 consecutive patients. Patient Saf Surg. 2020 Sep 29;14(1):36.

- Bhaijee F, Krige JEJ, Locketz ML, Kew MC. Liver resection for non-cirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma in South African patients. South Afr J Surg Suid-Afr Tydskr Vir Chir. 2011 Apr;49(2):68–74.

- Felli E, Urade T, Al-Taher M, Felli E, Barberio M, Goffin L, et al. Demarcation Line Assessment in Anatomical Liver Resection: An Overview. Surg Innov. 2020 Oct;27(5):424–30.

- Mwanga AH, Mwakipesile JD, Kitua DW, Ringo YE. A Comprehensive Overview of In-patients Treated for Hepatocellular Carcinoma at a Tertiary Care Facility in Tanzania. J Ren Hepatic Disord. 2023 Mar 11;7(1):22–7.

- Elfrink AKE, van Zwet EW, Swijnenburg RJ, den Dulk M, van den Boezem PB, Mieog JSD, et al. Case-mix adjustment to compare nationwide hospital performances after resection of colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;47(3, Part B):649–59.

- Bhalla S, Mcquillen B, Cay E, Reau N. Preoperative risk evaluation and optimization for patients with liver disease. Gastroenterol Rep. 2024 Jan 1;12:goae071.

- Olthof PB, Elfrink AKE, Marra E, Belt EJT, van den Boezem PB, Bosscha K, et al. Volume–outcome relationship of liver surgery: a nationwide analysis. Br J Surg. 2020 Jun 1;107(7):917–26.

- Abdelhameed HF, El-Badry AM. Cirrhosis aggravates the ninety-day mortality after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int Surg J. 2019 Jul 25;6(8):2869–75.

- Chor CYT, Mahmood S, Khan IH, Shirke M, Harky A. Gastrointestinal complications following cardiac surgery. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2020 Nov 1;28(9):621–32.

- Görgec B, Fichtinger RS, Ratti F, Aghayan D, Van der Poel MJ, Al-Jarrah R, et al. Comparing practice and outcome of laparoscopic liver resection between high-volume expert centres and nationwide low-to-medium volume centres. Br J Surg. 2021 Aug 1;108(8):983–90.

- Feldbrügge L, Wabitsch S, Benzing C, Krenzien F, Kästner A, Haber PK, et al. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic liver resection in patients with a history of abdominal surgeries. HPB. 2020 Aug 1;22(8):1191–6.

- Fischer A, Fuchs J, Stravodimos C, Hinz U, Billeter A, Büchler MW, et al. Influence of diabetes on short-term outcome after major hepatectomy: an underestimated risk? BMC Surg. 2020 Nov 30;20(1):305.

- Troisi RI, Berardi G, Morise Z, Cipriani F, Ariizumi S, Sposito C, et al. Laparoscopic and open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with Child–Pugh B cirrhosis: multicentre propensity score-matched study. Br J Surg. 2021 Feb 1;108(2):196–204.

- Watanabe Y, Aikawa M, Kato T, Takase K, Watanabe Y, Okada K, et al. Influence of Child–Pugh B7 and B8/9 cirrhosis on laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2023 Feb 1;37(2):1316–33.

- Tada T, Kumada T, Hiraoka A, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, et al. Impact of modified albumin–bilirubin grade on survival in patients with HCC who received lenvatinib. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 14;11(1):14474.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients.

| Variable |

category |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

| Age (years) |

18 to 35 |

5 |

27.8 |

| 36 to 50 |

3 |

16.7 |

| >50 |

10 |

55.6 |

| Sex |

Male |

4 |

22.2 |

| Female |

14 |

77.8 |

| Residence |

Dodoma |

9 |

50 |

| Upcountry |

9 |

50 |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients.

| Variables |

Category |

Frequency (N) |

Percentage (%) |

| Alcohol use |

Yes |

3 |

16.7 |

| No |

5 |

83.3 |

| History of cigarette smoking |

Yes |

0 |

0 |

| No |

18 |

100 |

| History of other chronic disease |

Yes |

7 |

38.9 |

| No |

11 |

61.1 |

| Hep B |

Positive |

1 |

5.6 |

| Negative |

17 |

94.4 |

| Hep C |

Positive |

2 |

11.1 |

| Negative |

16 |

88.9 |

| HIV |

Positive |

1 |

5.6 |

| Negative |

17 |

94.4 |

| Biopsy findings |

Malignant |

7 |

38.9 |

| benign |

11 |

61.1 |

Table 3.

Outcomes of Liver ressection.

Table 3.

Outcomes of Liver ressection.

| Variable |

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Complications |

Yes |

7 |

38.9 |

| No |

11 |

61.1 |

| ICU stay |

Yes |

6 |

33.3 |

| No |

12 |

66.7 |

| In hospital death |

Yes |

3 |

16.7 |

| No |

16 |

83.3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).