Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

20 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study Groups

- MAFLD-negative HCC

- MAFLD-positive HCC

- Overweight or obesity, based on World Health Organization (WHO) definitions (adjusted for Asian patients).

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Metabolic dysregulation.

- Radiologic or histologic evidence of hepatic steatosis or steatohepatitis.

- Waist circumference >102 cm (men) or >88 cm (women), adjusted for Asian patients

- Systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, or current use of antihypertensive medications

- Serum triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or current use of lipid-lowering medications

- High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <40 mg/dL (men) or <50 mg/dL (women)

- Prediabetes, defined as fasting glucose 100–125 mg/dL or HbA1c 5.7–6.4%

- C-reactive protein (CRP) >2 mg/L

Data Collection and Definitions

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

- OS defined as the time from hepatic resection to death from any cause

- PFS defined as the time from hepatic resection to first radiographic evidence of HCC recurrence

- Morbidity and mortality rates at 90-day and 1-year

Follow up

Statistical Analysis

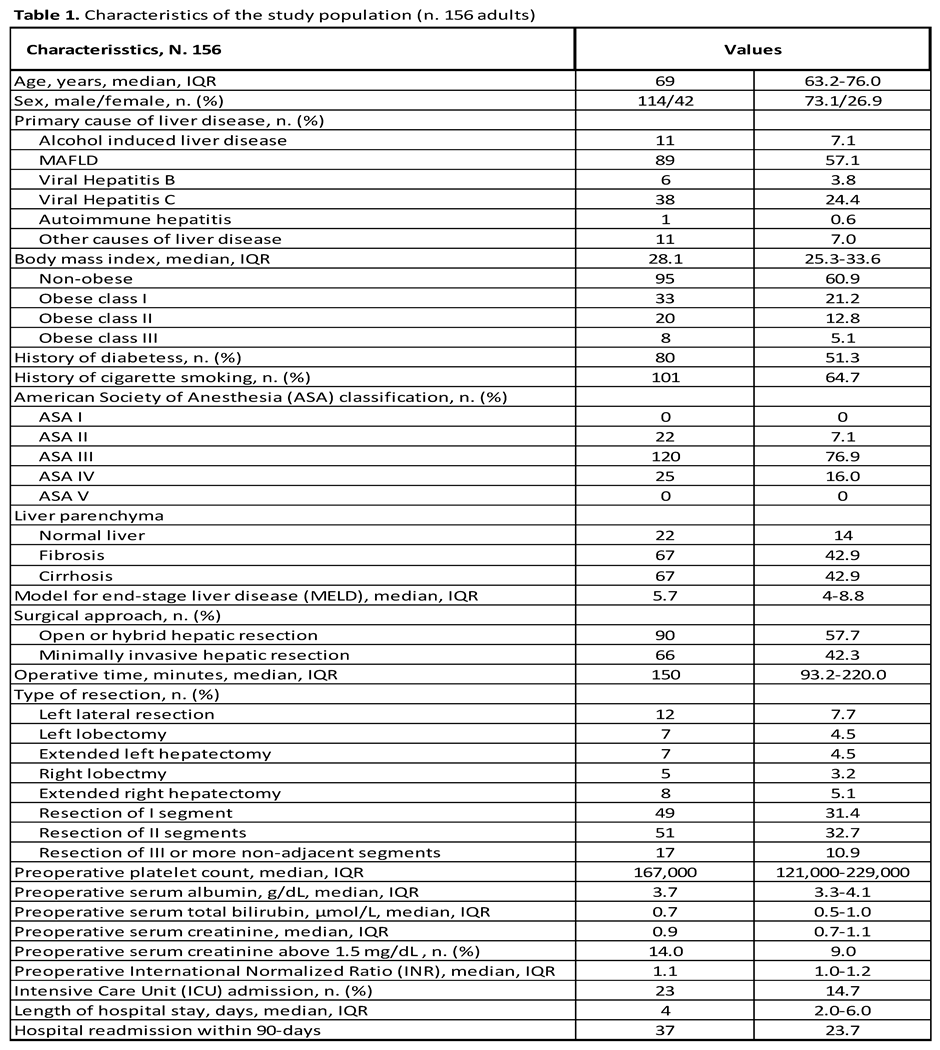

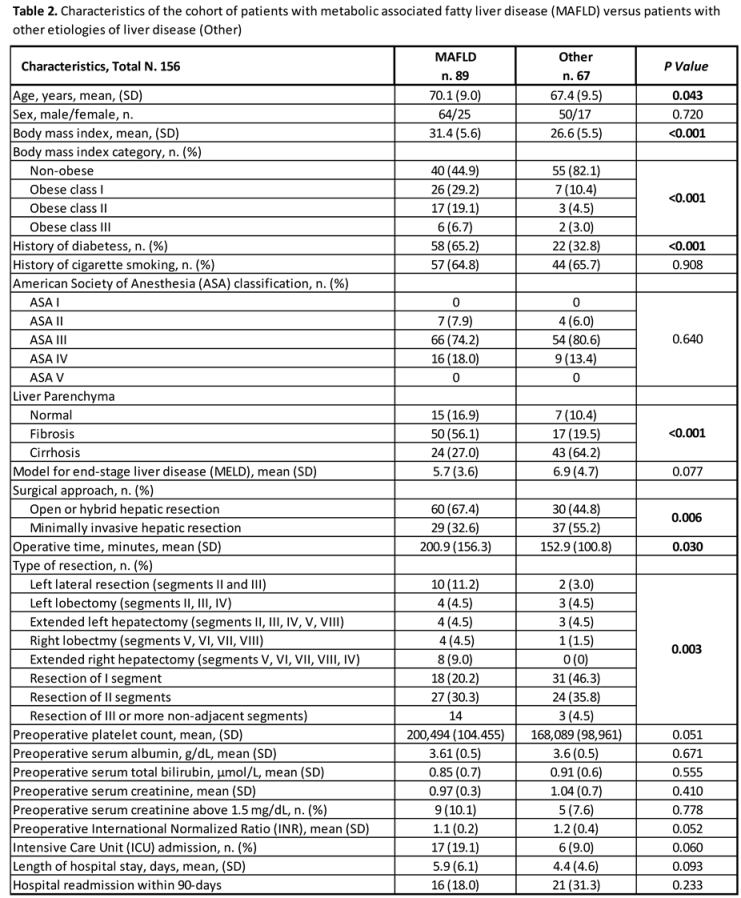

Results

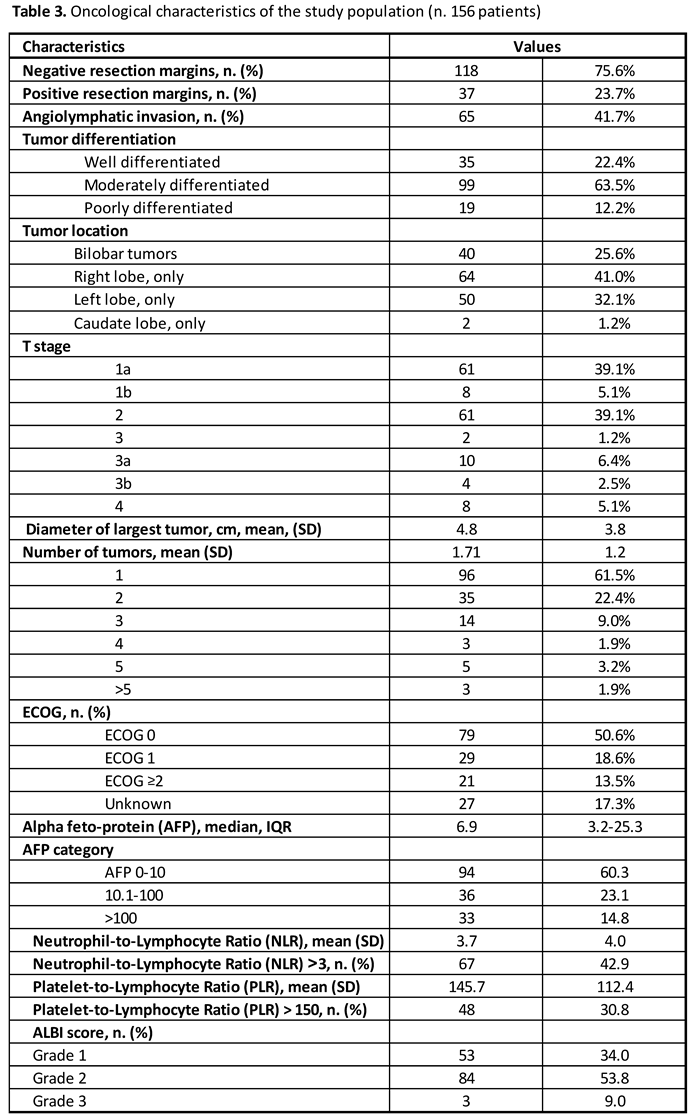

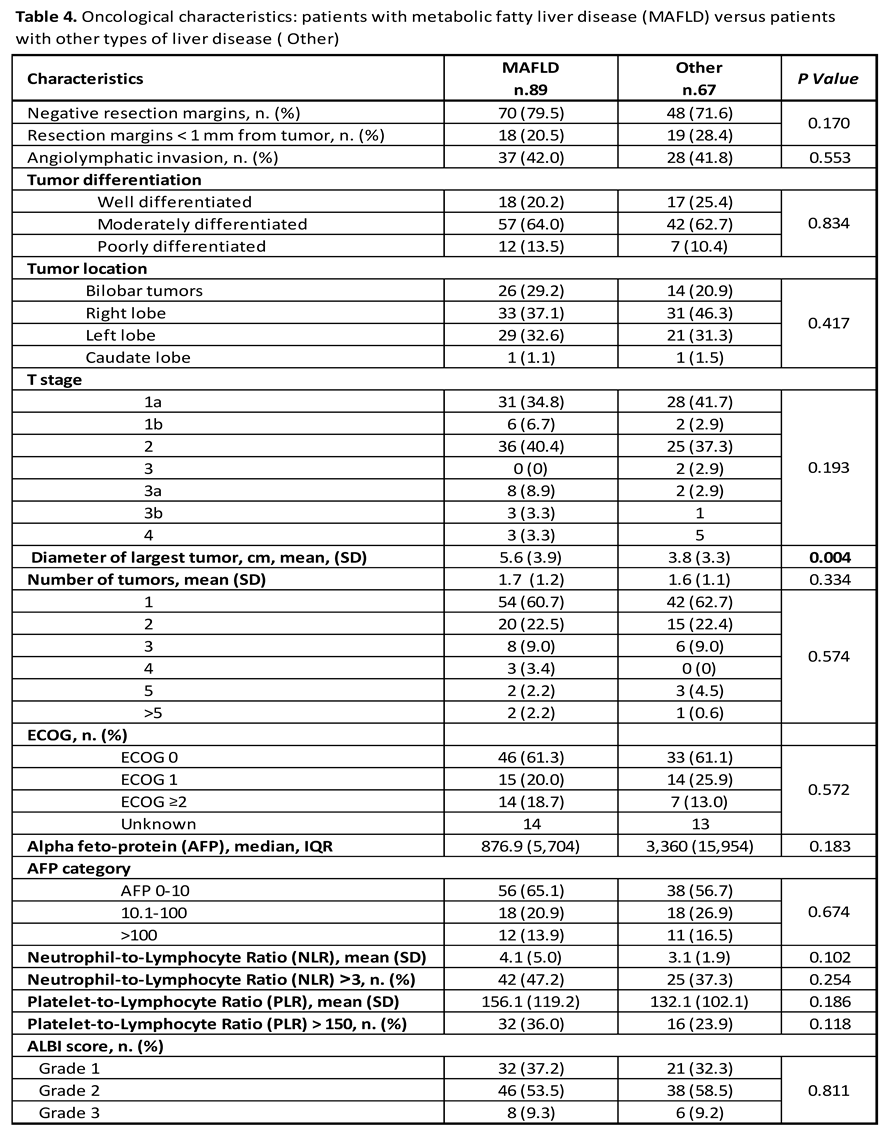

Oncological Characteristics

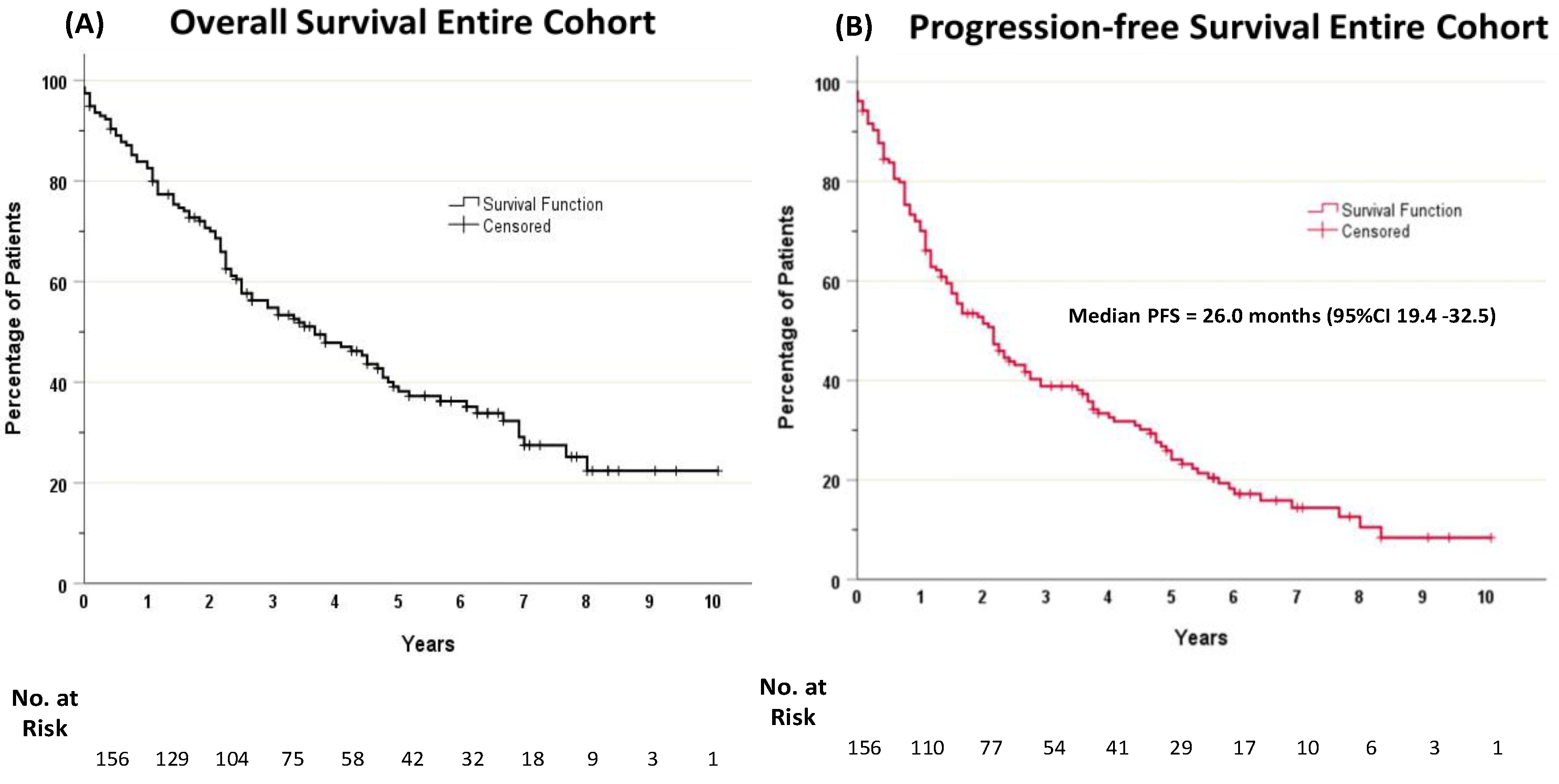

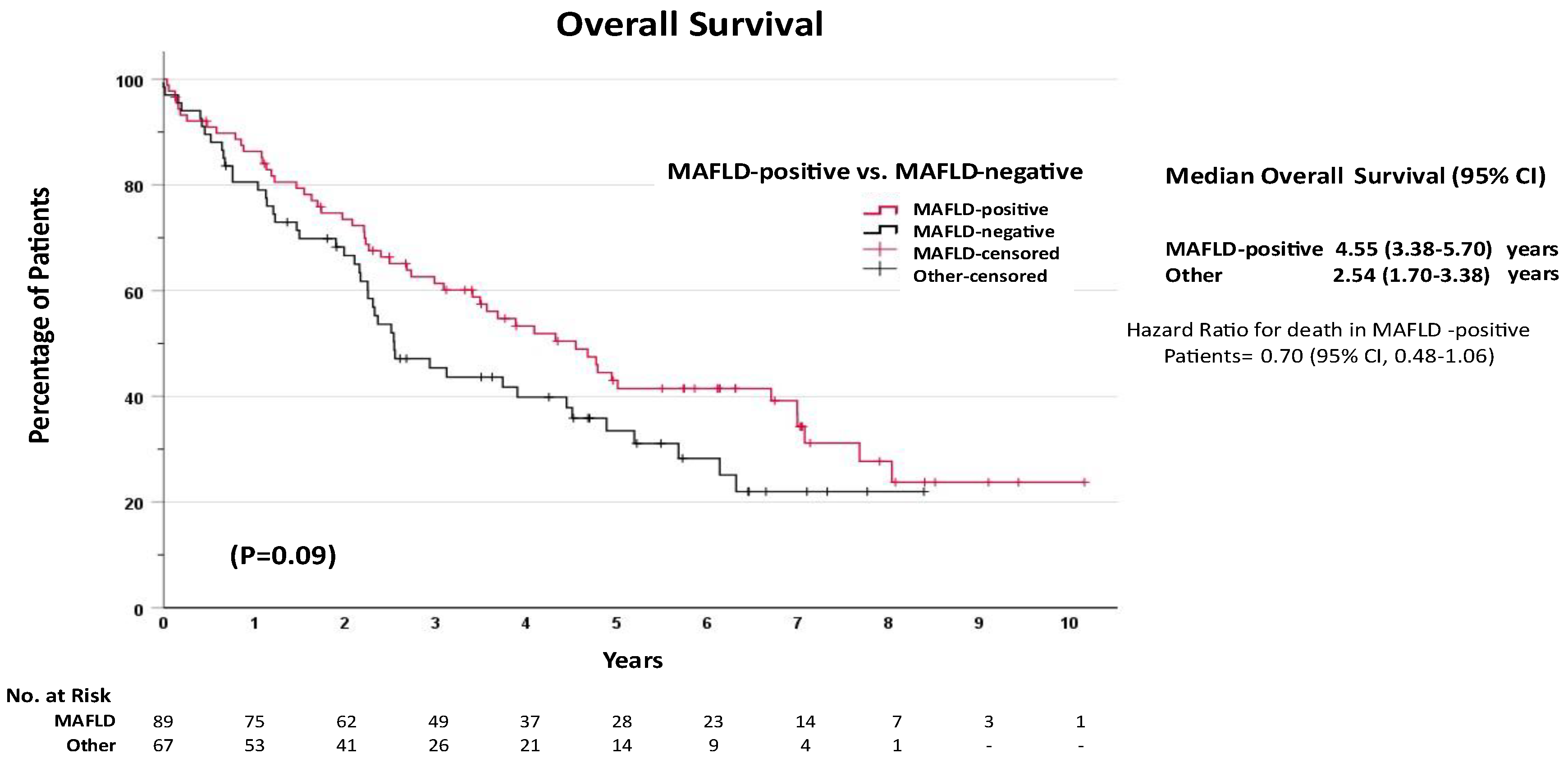

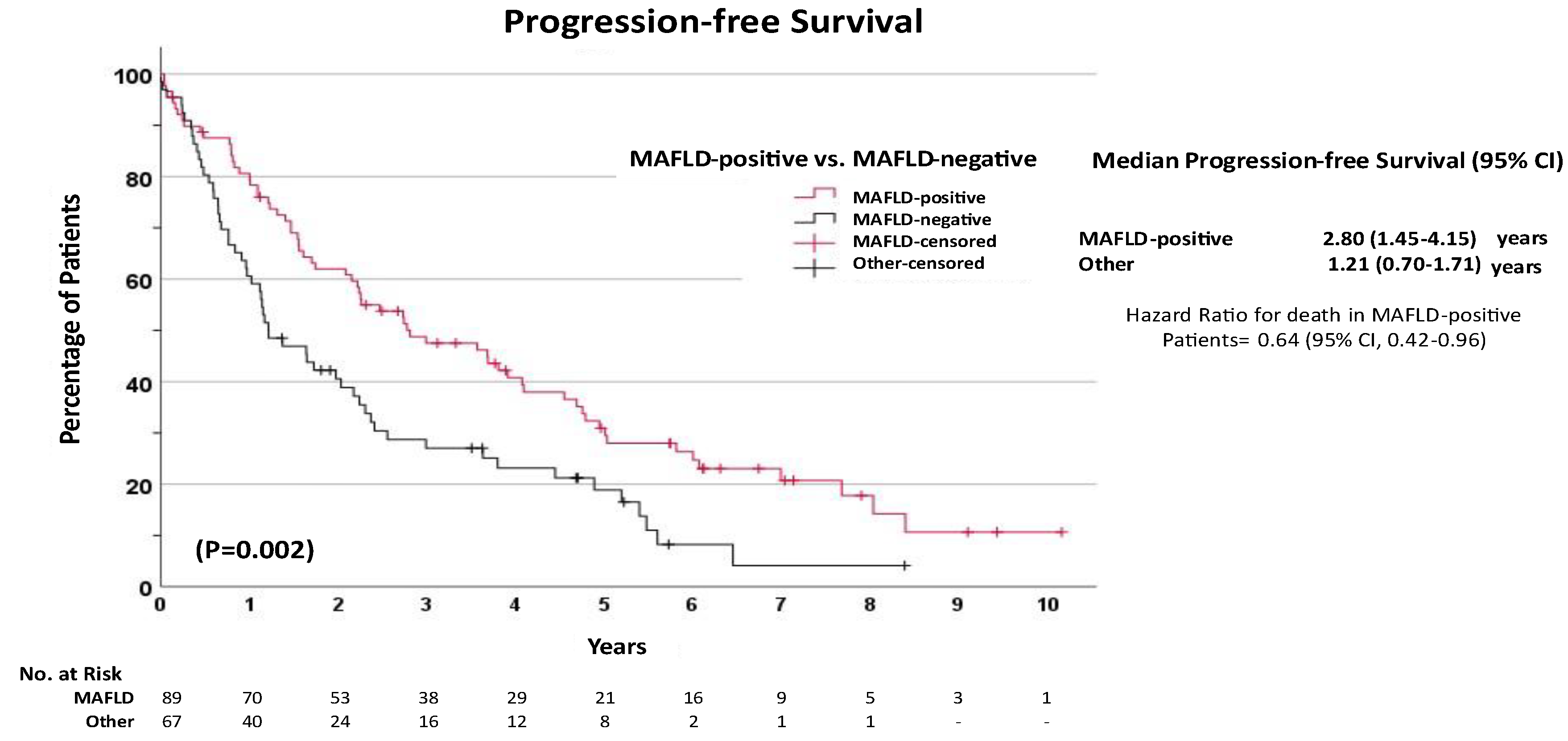

Unadjusted Survival Analysis

Multivariate Survival Analysis

Discussion

Financial Support

Contributions

Supplementary Materials

Conflict of interest

References

- Molinari, M.; Kaltenmeier, C.; Samra, P.B.; et al. Hepatic Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 7226 Patients. Ann Surg Open. 2021, 2, e065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beudeker, B.J.B.; Guha, R.; Stoyanova, K.; JNMIJ; de Man, R.A.; Sprengers, D.; Boonstra, A. Cryptogenic non-cirrhotic HCC: Clinical, prognostic and immunologic aspects of an emerging HCC etiology. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocha, C.; Xie, C. Hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—one of a kind or two different enemies? Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.H.; Yu, M.C.; Chan, K.M.; et al. Prognostic effect of steatosis on hepatocellular carcinoma patients after liver resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011, 37, 618–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertle, J.; Dechêne, A.; Sowa, J.-P.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of apparent cirrhosis. International Journal of Cancer. 2011, 128, 2436–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, M.; Wiede, F.; Dodd, G.T.; et al. Obesity drives STAT-1-dependent NASH and STAT-3-dependent HCC. Cell. 2018, 175, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent-Puig, P.; Zucman-Rossi, J. Genetics of hepatocellular tumors. Oncogene. 2006/06/01 2006, 25, 3778–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.-J.; Fong, Y.; Cho, S.-J.; et al. Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in American and Asian patients by tissue array analysis. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012, 106, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-W.; Chau, G.-Y.; Hung, H.-H.; et al. Impact of Steatosis on Prognosis of Patients with Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Hepatic Resection. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015/07/01 2015, 22, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, T.; Shirai, Y.; Sakata, J.; Korita, P.V.; Ajioka, Y.; Hatakeyama, K. Surgical Outcomes for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2011/08/01/ 2011, 15, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganò, L.; Conci, S.; Cescon, M.; et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic syndrome: A multicenter matched analysis with HCV-related HCC. Journal of Hepatology. 2015/07/01/ 2015, 63, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Lyu, H.; He, Y.; Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, F. Comparison of Hepatectomy for Patients with Metabolic Syndrome-Related HCC and HBV-Related HCC. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2018/04/01/ 2018, 22, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Brubaker, L.; Curfman, G. The 2024 Revision to the Declaration of Helsinki: Modern Ethics for Medical Research. JAMA. 2025, 333, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007, 370, 1453–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.G.; Choi, S.C.; Goh, M.J.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH (National Heart L, and Blood Institute). What is Metabolic Syndrome? 02-28-2025, 2025. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/metabolic-syndrome?

- Hendrix, J.M.; Garmon, E.H. American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. StatPearls. 2025.

- Azam, F.; Latif, M.F.; Farooq, A.; Tirmazy, S.H.; AlShahrani, S.; Bashir, S.; Bukhari, N. Performance Status Assessment by Using ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) Score for Cancer Patients by Oncology Healthcare Professionals. Case Rep Oncol. Sep- 2019, 12, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananchuensook, P.; Sriphoosanaphan, S.; Suksawatamnauy, S.; et al. Validation and prognostic value of EZ-ALBI score in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma treated with trans-arterial chemoembolization. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M. Newly Developed Modified ALBI Grade Shows Better Prognostic and Predictive Value for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Huang, X.; Pei, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, H. MRI Features and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR)-Based Nomogram to Predict Prognosis of Microvascular Invasion-Negative Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2025, 12, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Shelat, V.G. The role of platelet-lymphocyte ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a valuable prognostic marker. Transl Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 4231–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; Qi, J.; et al. Prognostic value of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 35378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Cai, J.Y.; Li, H.; et al. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio as Prognostic Predictors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Various Treatments: a Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017, 44, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvaruso, V.; Burroughs, A.K.; Standish, R.; et al. Computer-assisted image analysis of liver collagen: relationship to Ishak scoring and hepatic venous pressure gradient. Hepatology. 2009, 49, 1236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenci, P.; Aires, R.; Beavers, K.L.; et al. Predictive value of FIB-4 and APRI versus METAVIR on sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C patients. Hepatol Int. 2014, 8, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Liu, P.H.; Hsia, C.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Huo, T.I. Metavir Fibrosis Stage in Hepatitis C-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Association with Noninvasive Liver Reserve Models. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020, 24, 1860–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Fu, Y.P.; Wang, T.; et al. Metavir and FIB-4 scores are associated with patient prognosis after curative hepatectomy in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study at two centers in China. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 1774–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eps. EASL Policy Statement Risk-based Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Among Patients with Cirrhosis. 02-28-2025, 2025. Accessed 02-25-2025, 2025. https://easl.eu/publication/easl-policy-statement-risk-based/.

- Chernyak, V.; Fowler, K.J.; Kamaya, A.; et al. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI-RADS) Version 2018: Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in At-Risk Patients. Radiology. 2018, 289, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertle, J.; Dechene, A.; Sowa, J.P.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of apparent cirrhosis. Int J Cancer. 2011, 128, 2436–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, M.; Trauner, M.; Peck-Radosavljevic, M.; Sieghart, W. Cancer and liver cirrhosis: implications on prognosis and management. ESMO Open. 2016, 1, e000042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Muller-Butow, V.; Franz, C.; Hinz, U.; Longerich, T.; Buchler, M.W.; Schemmer, P. Factors predictive of survival after stapler hepatectomy of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multivariate, single-center analysis. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 767–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.N.; Lee, W.C.; Chen, M.F.; Tsay, P.K. Predictors of long-term disease-free survival after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: two decades of experience at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003, 10, 916–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.W.; Chen, Y.S.; Lin, C.C.; et al. Significant predictors of overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0202650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.; Fartoux, L.; Goumard, C.; Scatton, O.; Wendum, D.; Rosmorduc, O.; Ratziu, V. Temporal trends, clinical patterns and outcomes of NAFLD-related HCC in patients undergoing liver resection over a 20-year period. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017, 46, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, T.; Shirai, Y.; Sakata, J.; Korita, P.V.; Ajioka, Y.; Hatakeyama, K. Surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011, 15, 1450–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, T.; Hatano, E.; Sakurai, T.; et al. Impact of Hepatic Steatosis on Disease-Free Survival in Patients with Non-B Non-C Hepatocellular Carcinoma Undergoing Hepatic Resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015, 22, 2226–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.R.; Njei, B.; Nguyen, M.H.; Nguyen, A.; Lim, J.K. Survival after treatment with curative intent for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with vs without non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 10612017, 46, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, P.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, A.; Garcia-Monzon, C.; Valverde, A.M. Understanding lipotoxicity in NAFLD pathogenesis: is CD36 a key driver? Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ande, S.R.; Nguyen, K.H.; Gregoire Nyomba, B.L.; Mishra, S. Prohibitin-induced, obesity-associated insulin resistance and accompanying low-grade inflammation causes NASH and HCC. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 23608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.D.W.; George, J.; Qiao, L. From MAFLD to hepatocellular carcinoma and everything in between. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022, 135, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Ong, Y.; et al. Liver resection versus liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma within Milan criteria: a meta-analysis of 18,421 patients. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2022, 11, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

| HR | 95% Confidence | P Value | Adjusted HR | 95% Confidence | P Value | |||

| LCI | UCI | LCI | UCI | |||||

| Diagnosis of liver disease | ||||||||

| MAFLD-negative | 1 | Reference | - | 1 | Reference | |||

| MAFLD-positive | 0.70 | 0.48 | 1.06 | 0.093 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 1.84 | 0.785 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 1.62 | 1.09 | 2.42 | 0.019 | 2.32 | 1.16 | 4.64 | 0.018 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.009 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.223 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Male | 1.22 | 0.77 | 1.94 | 0.400 | 1.34 | 0.72 | 2.48 | 0.356 |

| Diabetes | 0.99 | 0.67 | 1.47 | 0.960 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 1.72 | 0.938 |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.87 | 0.57 | 1.33 | 0.522 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 1.03 | 0.062 |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| Non-obese | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Obese | 0.663 | 0.434 | 1.011 | 0.056 | 0.76 | 0.41 | 1.40 | 0.380 |

| ECOG | ||||||||

| ECOG 0 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| ECOG 1 | 1.35 | 0.81 | 2.27 | 0.253 | 1.74 | 0.95 | 3.18 | 0.075 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 1.89 | 1.11 | 3.24 | 0.019 | 2.67 | 1.29 | 5.50 | 0.008 |

| Number of tumors | ||||||||

| Single lesion | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Two lesions | 1.22 | 0.75 | 1.99 | 0.418 | 1.26 | 0.66 | 2.40 | 0.484 |

| Three or more lesions | 1.33 | 0.78 | 2.26 | 0.294 | 1.31 | 0.61 | 2.80 | 0.491 |

| Alpha feto-protein | ||||||||

| 0-10 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| 10.1-100 | 1.194 | 0.729 | 1.955 | 0.482 | 1.39 | 0.73 | 2.67 | 0.319 |

| >100 | 1.821 | 1.069 | 3.100 | 0.027 | 2.89 | 1.45 | 5.76 | 0.003 |

| Cellular differentiation | ||||||||

| Well differentiated | 1 | Reference | - | 1 | Reference | - | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.305 | 0.089 | 1.042 | 0.058 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 2.06 | 0.162 |

| Poorly differentiated | 0.469 | 0.147 | 1.500 | 0.202 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 4.13 | 0.386 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.634 | 0.181 | 2.232 | 0.478 | 1.05 | 0.52 | 2.12 | 0.894 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||||

| T1 | 1 | Reference | - | 1 | Reference | - | ||

| T2 | 1.086 | 0.693 | 1.700 | 0.719 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 2.00 | 0.817 |

| T3 | 1.98 | 1.055 | 3.715 | 0.033 | 2.91 | 0.92 | 9.18 | 0.069 |

| T4 | 2.464 | 1.098 | 5.529 | 0.029 | 1.91 | 0.61 | 6.01 | 0.269 |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) >3 | 1.506 | 1.012 | 2.242 | 0.043 | 1.44 | 0.83 | 2.48 | 0.196 |

| Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) > 150 | 0.861 | 0.557 | 1.330 | 0.499 | 1.01 | 0.52 | 1.96 | 0.986 |

| ALBI score | ||||||||

| Grade 1 | 1 | Reference | - | 1 | Reference | - | ||

| Grade 2 | 1.717 | 1.074 | 2.746 | 0.024 | 1.05 | 0.57 | 1.92 | 0.876 |

| Grade 3 | 2.121 | 1.017 | 4.424 | 0.045 | 0.73 | 0.27 | 1.98 | 0.536 |

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

| HR | 95% Confidence | P Value | Adjusted HR | 95% Confidence | P Value | |||

| LCI | UCI | LCI | UCI | |||||

| Diagnosis of liver disease | 0.003 | 0.845 | ||||||

| MAFLD-negative | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| MAFLD-positive | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.82 | 0.003 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 1.19 | 0.139 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 1.69 | 1.18 | 2.43 | 0.004 | 1.82 | 0.86 | 3.85 | 0.117 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.262 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.862 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Male | 1.31 | 0.86 | 1.99 | 0.207 | 1.52 | 0.70 | 3.20 | 0.284 |

| Diabetes | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.753 | 1.37 | 0.72 | 2.61 | 0.334 |

| Cigarette smoking | 1.03 | 0.70 | 1.50 | 0.898 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 1.19 | 0.144 |

| Obesity | 0.641 | 0.44 | 0.934 | 0.021 | 1.10 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 0.773 |

| ECOG | 0.655 | 0.378 | ||||||

| ECOG 0 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| ECOG 1 | 1.19 | 0.74 | 1.92 | 0.468 | 1.42 | 0.69 | 2.94 | 0.336 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 2.04 | 0.462 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 9.52 | 0.998 |

| Number of tumors | 0.004 | 0.016 | ||||||

| Single lesion | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Two lesions | 1.86 | 1.20 | 2.89 | 0.005 | 2.34 | 1.12 | 4.93 | 0.024 |

| Three or more lesions | 1.82 | 1.14 | 2.91 | 0.012 | 3.10 | 1.27 | 7.60 | 0.013 |

| Alpha feto-protein | 0.015 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 0-10 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| 10.1-100 | 1.44 | 0.93 | 2.22 | 0.100 | 1.68 | 0.97 | 2.93 | 0.065 |

| >100 | 2.00 | 1.21 | 3.30 | 0.007 | 3.12 | 1.59 | 6.09 | <0.001 |

| Cellular differentiation | 0.857 | 0.364 | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.69 | 0.21 | 2.29 | 0.547 | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.58 | 0.898 |

| Poorly differentiated | 0.72 | 0.23 | 2.30 | 0.584 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 2.31 | 0.905 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 1.07 | 0.75 | 1.54 | 0.697 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 1.29 | 0.184 |

| Tumor stage | 0.096 | 0.658 | ||||||

| T1 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| T2 | 1.11 | 0.74 | 1.65 | 0.615 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 1.24 | 0.249 |

| T3 | 1.67 | 0.92 | 3.02 | 0.092 | 1.57 | 0.71 | 3.47 | 0.267 |

| T4 | 2.23 | 1.05 | 4.72 | 0.037 | 1.80 | 0.73 | 4.47 | 0.204 |

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) >3 | 1.50 | 1.04 | 2.14 | 0.028 | 1.43 | 0.94 | 2.19 | 0.098 |

| Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) > 150 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 1.14 | 0.189 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.85 | 0.996 |

| ALBI score | 0.012 | 0.972 | ||||||

| Grade 1 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Grade 2 | 1.56 | 1.04 | 2.33 | 0.032 | 1.01 | 0.59 | 1.74 | 0.968 |

| Grade 3 | 2.55 | 1.31 | 4.94 | 0.006 | 1.11 | 0.46 | 2.71 | 0.817 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).