1. Introduction

Digitalization of work processes includes diverse technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), advanced robotics, big data, algorithms, and mobile communication technologies, several of which are widely adopted in platform-mediated work (PMW) [

1]. PMW refers to paid employment facilitated through digital platforms that act as intermediaries between workers and customers [

2] (Author). This three-way employment relationship is a defining feature of the platform economy [

1,

3,

4]. PMW tasks are mediated via apps or websites, and the number of individuals engaged in such work is rapidly growing. As of 2022, the European Council estimated there were 28.3 million platform workers in the EU, a figure expected to reach 43 million by 2025 [

5]. Particularly there are many young workers employed in this growing economy (Author 1).

The platform economy, or gig economy, is mediated by digital platforms that regulate work through algorithmic management, where algorithms oversee task distribution, worker performance, and customer interactions [

6,

7], e.g., food delivery couriers depend on apps to allocate tasks, dictate routes, and facilitate customer interactions [

2]. Unlike traditional employment relationships, platform workers are often classified as independent contractors, leaving them without standard employee protections, such as access to occupational health and safety (OHS) measures. As a result, the responsibility for managing risks often fall on the workers themselves [

8,

9] (Author 1).

Digital mediation of work is not a neutral process. The use of algorithmic management has been shown to intensify labor by increasing work pace, extending surveillance, and creating job insecurity [

4,

10]. Additionally, digital platforms may amplify psychosocial risks by exposing workers to customer abuse, detailed monitoring, and the pressures of ratings-based evaluations [

11,

12]. In particular, young workers are vulnerable to these risks (Author 3). These risks are compounded by the lack of preventative structures traditionally found in standard employment. To understand how digital platforms shape the risk of work-related harassment, this study draws on the concept of affordances. Originally developed by ecological psychologist James J. Gibson [

13], affordances refer to the action possibilities that objects or environments offer to an organism. Crucially, affordances are relational – they exist not as inherent properties of objects but in the relationship between the user and the technology within specific contexts [

13]. The concept of affordances is particularly relevant for analyzing PMW, as it captures the dynamic ways in which digital technologies both enable and constrain worker experiences. Rather than viewing platforms as neutral tools, an affordance lens emphasizes how technological features interact with social structures to shape specific possibilities for action. This includes not only opportunities for task execution and coordination but also the possible emergence of harmful dynamics, such as harassment and abuse.

This paper contributes to ongoing research in the field of OHS by examining how digital labor platforms shape interactions between young platform workers and their customers. In doing so, the study investigates how digital technologies shape work-related vulnerabilities and may amplify the risks of harassment and abusive behavior in PMW.

This leads us to the following research questions:

- 1)

How do platform affordances shape online and offline encounters between platform workers and their customers in PMW?

- 2)

How do platform affordances shape the emergence and experience of harassment and abusive behavior directed at young workers engaged in PMW?

2. Harassment and Abusive Behavior in PMW

2.1. Harassment and Abusive Behavior Defined

The Violence and Harassment Convention, adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 2019, defines violence and harassment as:

“a range of unacceptable behaviours and practices, or threats thereof, whether a single occurrence or repeated, that aim at, result in, or are likely to result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm, [including] gender-based violence and harassment” [

14].

ILO

’s Violence and Harassment Convention No. 190 [

14] explicitly extends this definition to include forms of harassment and violence enabled by digital technologies. This includes work-related information and communication technologies (ICT), such as emails, social media, and other digital platforms. As such, the Convention acknowledges that violence and harassment are no longer confined to physical workplace and working hours, as digital connectivity is present much of our waking hours. Moreover, the nature of digital technologies enables the rapid and persistent dissemination of abusive content, often in ways that are difficult to trace or control [

15]. This shift highlights the need to better understand how digital infrastructures may facilitate or amplify experiences of harassment in contemporary work environments, as reflected in the ILO Convention referred to above.

2.2. Risks of Harassment in PMW

An emerging body of literature engages with OSH within PMW. Despite the variations between platforms, both concerning the nature of the work performed, and the context of where it is performed, “platforms represent the place where social relations between a worker and a client or consumer become relations of production” (Gandini, 2018, p. 1046). However, it has been shown that platform workers

’ exposure to risks is highly dependent on whether the PMW is performed online or offline [

16] (Author 1). Offline harassment in PMW can, for example, occur if the platform worker performs tasks like cleaning, childcare or other forms of domestic work in a customer

’s home. This is often conceptualized as crowd work [

17]. Whereas work that is both mediated and performed online, such as translation or graphic work, primarily entails risk of digital harassment. According to Huws et al. [

17]:

“Crowd work carried out in other people’s homes can be extremely varied. Alongside the potential for accidents, such crowd workers may perform emotional labor, which is known to carry psychosocial risks (…). Such work may also result in interpersonal violence or harassment, both to workers and from them” [

17]

(Huws et al., 2016, p. 10).

The platform-mediation of work has proved to pose particular risks to the mental health and wellbeing of platform workers: Evaluation through rating systems can cause stress among workers [

16,

18,

19], and has negative psychosocial impacts [

20]. This is also found by Gregory [

21], who describes how:

“(…) ‘algorithmic uncertainty’ about how worker data are gathered and used makes it impossible for workers to parse their own sense of risk and to determine when the work is ‘worth it’ or not.” [

21].

Digitalization of work activities, such as algorithmic management, can also lead to intrusive monitoring practices and forms of ‘cyberbullying’ [

22,

23]. A body of research has highlighted how platform workers may face difficulties in navigating or resisting transgressive customer behaviors due to fears of receiving poor ratings, and thereby their ability to maintain an income [

4,

8,

23,

24].

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the platform-mediation of work does more than impose top-down management control, as the risk extends beyond individual interactions; they also have the potential to re-configure the social relationships emerging from the relational framework of the platform. In the following section, we will explore how these relational aspects may influence PMW.

2.3. The Relational Aspects of PMW

Although the evidence base is still emerging, several peer

-reviewed studies link affordances of digital labor platforms to an elevated risk of harassment, discrimination, and other forms of abuse against workers [

25,

26,

27]. The study of Rosenblat et al. [

26] demonstrates that the high

-level affordance of customer

-driven ratings not only measures service quality but also redistributes power and subject drivers to psychosocial strain. In alignment, (Author 4) emphasizes how PMW calls for the performance of emotional labor. Stringhi [

27] shows that UpWork’s assumed “neutral” design features create gendered inequality through so-called high-level affordances that expose female freelancers (“Up

-workers”) to several forms of cyber

-violence and, in turn, reshape their labor prospects. Alacovska, Bucher & Fieseler [

25] introduce the concept ‘algorithmic paranoia’, a state of mistrust, anxiety and anticipatory fear that gig workers develop when platform algorithms seem opaque, arbitrary and punitive. They frame this effect as relational, emerging from the interplay between the algorithm itself, clients and fellow workers.

Prior research has demonstrated that the affordances of digital labor-platform technologies simultaneously expand and circumscribe worker agency – an issue central to safety-science inquiries into risk, control and the power dimensions of PMW. This includes symbolic forms of power, which foster narratives of empowerment, autonomy, and flexibility designed to tempt workers to view themselves as their own boss, micro-entrepreneurs, or courier partners [

28]. Shapiro [

29] specifically foregrounds the ‘log on and log off’ affordance, whereby platform workers at any time during the day can activate or deactivate the app and interpret this capability as evidence of temporal autonomy. However, other scholars have shown that this autonomy is moderated by continuous surveillance and algorithmic control, which introduce new operational hazards and uncertainty for platform workers. Building on this perspective, Jarrahi et al. [

30] illustrates ‘the paradoxical affordances’ of labor platforms: the same socio-technical features that facilitate individual flexibility also serve managerial control. Lauersen et al. [

31] label this tension the ‘double autonomy paradox’, observing that algorithmic management narrows young workers’ discretion precisely while permitting them to choose when and where to ‘log on and log off’, a classic coupling of nominal freedom with hidden constraints. Gregory [

21] further demonstrates that platform-mediated riders adopt informal strategies to privatize, normalize and minimize risk, that fall short because of the ‘algorithmic uncertainty’, a point also suggested by Alacovska et al [

25]. Integrating these perspectives, the literature indicates that platform technologies have no single, deterministic effect on the practice of users, rather, practices and outcomes emerge from the dynamic interplay between platform technologies and workers’ adaptive practices aimed at mitigating risk or gaining control over their work. This interplay is demonstrated by Salmon [

32] who employed the AcciMap systems

-thinking method [

33] to illustrate eight interacting socio

-technical layers shaping delivery riders’ everyday behavior and influencing their crash risk. Building on these insights, the analytical focus in studies of PMW must move beyond static, technological conceptions of digital platforms towards a more dynamic understanding of how platforms afford the interactions between workers, users and digital platforms. This study applie the concept of high-level affordances to capture the complex and evolving interrelations between platform design features, worker practices, and user behaviors, with particular attention to how these dynamics may give rise to risks such as harassment and abuse.

3. Theoretical Approaches to the Affordance Concept

3.1. The Concept of Affordances

The concept of affordances was originally developed in the field of ecological psychology and later adopted in design studies [

34]. Affordance originally refers to the possibilities for action offered by the environment to an organism [

13].

Gibson’s work focused on the direct visual perception, exploring how organisms perceive surfaces, layouts, colors, and textures in their surroundings, as elaborated in his book The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception [

13]. Vicente and Rasmussen [

35] extended Gibson’s insight from natural perception to complex socio-technical systems through their work with ‘Ecological Interface Design’ (EID), using interviews and observations in high-risk process control environments, such as industrial plants, nuclear power facilities, and air-traffic control rooms, they identified recurring events and structural features of the work environment that shape how operators perceive and respond to system dynamics.

‘High-level affordances’ are relational properties that become relevant in rule-based and knowledge-based modes of action, where the actor is consciously reasoning about goals, procedures or values [

35,

36,

37]. As Bucher and Helmond [

34] explain, high-level affordances capture the particular forms of engagement that a digital platform environment invites from its users.

3.2. The Platform-Sensitive Approach

Thus, Bucher & Helmond [

34] suggest considering a platform-sensitive approach while also seeing platforms as environments with specific possibilities and constraints. The various digital platforms are characterized by a specific combination of their infrastructural model as programmable and extendable infrastructures, and their economic model of connecting workers, users and advertisers [

34] and thus creating an extended relational network. When we investigate couriers bringing food from restaurants to end-users, it is an important infrastructural feature provided by the app, that there is GPS-tracking, which can log the couriers position in order to let the features of the app manage the remote work activities of couriers.

The notion of a platform-sensitive framework is meant to emphasize the specificity of platforms as a socio-technological environment that draw different users together and facilitate the relations and encounters between users and platform workers. Such a perspective enables us to analyze how platforms may afford different possibilities of relations between various types of platforms, users, and platform workers; and in turn, the significance of these relationships for the types of harassment and abusive behavior that platform workers may face.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design and Methods

This qualitative study combines the analytical approach with an integrated ‘Knowledge Transfer and Exchange’ framework (KTE) that engages key stakeholders at every stage – from data collection to interpreting results and translating insights into practice. To maximize the translation of knowledge into actionable solutions on digital platforms, we adopted this approach developed by the Canadian Institute for Work and Health, in which active user engagement is pivotal [

38,

39]. Accordingly, the research unfolded as a collaborative process that blended practice-based experience with scientific evidence to deepen understanding of harassing behaviors and ultimately prevent them [

40,

41,

42]. Prior to selection of participants and carrying out the interviews, three workshops were conducted with 13 stakeholders within the Danish platform economy. Throughout the project we followed Reardon et al.’s criteria for successful KTE exchange [

43], inviting stakeholders to co-develop and validate interview guides, interpret the emerging data, and refine the resulting recommendations - thereby ensuring that the findings are both rigorously grounded and readily usable in real-world settings. To validate the interview guide, it was pilot tested among the stakeholders, including what terminology to use about the subject of the planned interviews. We received the feedback that

‘abusive behavior

’ [in Danish ‘krænkelser’] is such a taboo term that the stakeholders advised us to avoid using it altogether to get any interviews at all. When recruiting informants for interviews, we therefore mostly referred to our research interests as: Hate, harassment, or unpleasant or transgressive experiences.

4.2. Selection Criteria and Recruitment of Participants

Following the earlier mentioned platform-sensitive framework we selected three types of platforms, representing different socio-technological environments, which draw together different users and platform workers. The three types of platforms represent both offline and online work:

- 1

Location-based (browser-mediated) labor platforms: Here the task is negotiated online between client and worker, but the work itself is carried out offline and locally. Typical examples include cleaning, repair, and other manual service jobs.

- 2

GPS-based, on-demand labor platforms: The work relies on real-time GPS tracking and is usually performed immediately after a request, for example, food delivery or ride-hailing.

- 3

Online (web-based) labor platforms: These handle predominantly computer-based tasks that are delivered entirely online, for example, translation, copywriting, or search-engine optimization. Some freelance consulting that takes place at the client’s premises may also be arranged through these platforms.

When recruiting interviewees, we followed these criteria:

Young workers (<= 30 years)

Representing at least one of the three types of labor platforms

A minimum of 0.5 years of experience with platform work, or at least 20 tasks performed.

Platform workers who have experiences of harassing, transgressive or abusive actions.

Varied gendered and racialized body signs.

Platform workers were recruited through open invitations to participate in the project via the platform’s newsletters and Facebook groups, but these were unsuccessful. Therefore, we chose to contact the young platform workers via various other channels: directly through their profile on the digital labor platforms, via their contact information on the platform, via Facebook groups, via the researchers’ stakeholder network, or contact if we saw couriers on the street with a logo or company equipment indicating affiliation with a platform.

A crucial challenge in recruiting interviewees was that some interviewees initially felt that they had no experience of hate, harassment, or unpleasant or transgressive experiences, but still talked about experiences in the interview situation, that we as researchers clearly interpreted as such. For some it may be that these types of experiences simply had become a norm that they were accustomed to dealing with [

44]. Alternatively, they found it difficult to assess whether the experiences they had had could be understood by others as harassing, transgressive or offensive. Some interviewees explicitly expressed, that they had forgotten unpleasant or transgressive experiences until they were sitting in the interview situation and/or did not want to be understood by the outside world as ‘offended’. It was important for us to leave room for the doubts and gray areas in the interview situation, as harassment is rarely experienced as clearly delineated and defined as such.

4.3. Interviews and Interview Guide

Qualitative research interviews provided us with nuanced and detailed knowledge [

45,

46]. The semi-structured interview guide served as a guideline, ensuring systematic coverage of every analytical theme. Questions were posed to platform workers in an open, exploratory manner [

46], inviting rich and nuanced narratives. Because harassment is a particularly sensitive topic, the interviewer devoted additional effort to building relationships, emphasizing confidentiality, and fostering a climate of trust throughout each conversation.

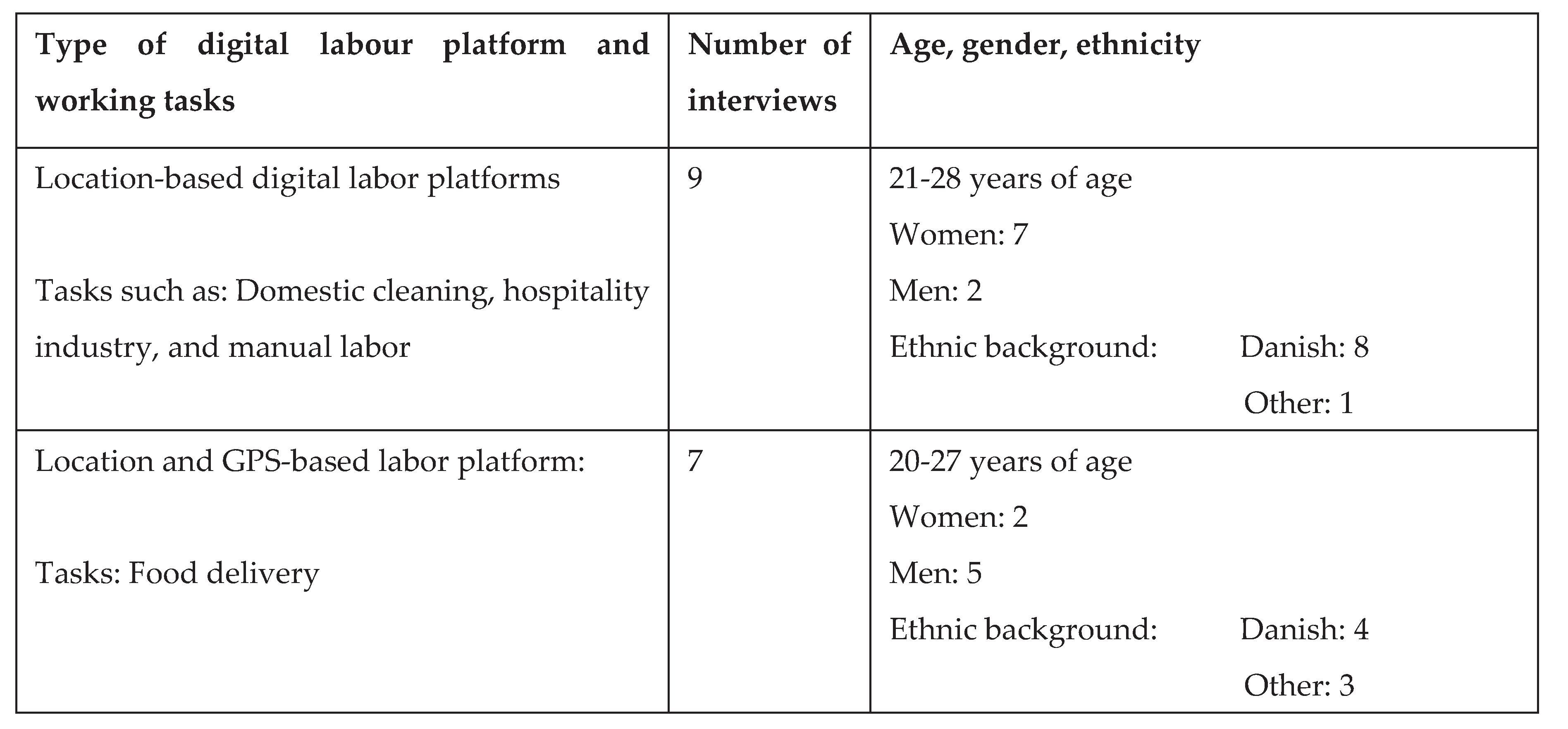

A total of 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted with young workers engaged in PMW. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and was carried out at a time and place convenient for the participants; 12 of the interviews were conducted online; four self identified as having a minority ethnic background. In some cases, the online format appeared to facilitate greater openness, as it allowed participants to speak more comfortably about personal experiences and episodes they had not articulated or actively reflected upon. While we have not explicitly enquired about our informants’ experience of the platform’s data infrastructures, these issues emerged when we enquired into the informants’ general experience of their work. The workers were asked about their life situation, work routines, pay, social and economic risks, health, and safety in general and harassment and violation specifically. The informants

’ personal information was handled in accordance with applicable GDPR regulations, and names of respondents are pseudonymized. Ethnic backgrounds were collected solely to explore whether cultural familiarity influenced experiences of platform work, in particular, harassment and discrimination are known to be associated with ethnic background [

47].

Table 1.

Overview of the 22 interviews by type of digital labor platform, working tasks, gender, age, and ethnicity, collected in the period 2018-2023.

Table 1.

Overview of the 22 interviews by type of digital labor platform, working tasks, gender, age, and ethnicity, collected in the period 2018-2023.

4.4. Analytical Approach

We analysed how high-level affordances in PMW shape online and offline relationships between young platform workers and their customers, and in turn, the significance of these relationships for the types and severity of harassment and abusive behavior in PMW. The interviews were transcribed and thematically coded [

48,

49] in NVivo 12 with codes developed according to the research questions. The identification of high-level affordances as particularly relevant to risks of harassment in platform-mediated work (PMW) emerged through an iterative and abductive analytical process. Rather than following a linear path, our analysis was shaped by ongoing engagement with empirical material and theoretical frameworks. A pivotal moment in this process was prompted by a specific quote encountered during the coding of interview data - a quote from a professional gamer, which is not included in this article (see Author 4, p. 181 for full analysis). In the quote a female gamer describes an episode where she by accident met a male follower offline at a cafe. A meeting that she characterized as highly transgressive and uncomfortable. This quote raised methodological questions about how to interpret the shift from an online professional interaction to an offline, unsolicited encounter. It pointed to the breakdown of spatial and relational boundaries between professional online settings and private offline settings, as well as underlying power asymmetries between the female gamer and the male follower.

This example became analytically generative. It guided us toward the affordance concept as a theoretical lens capable of capturing how digital platforms structure not only task-related possibilities but also shape social encounters and their associated risks. Our subsequent identification of the three high-level affordances was therefore informed by this abductive movement between data and theory, grounded in interdisciplinary scholarship on affordances and digital mediation.

The methodological insights outlined above were applied to the present interview data and used as an analytical lens to identify platform affordances. The analytic codes ‘abusive behavior’, ‘ways to deal with abusive behavior’ were first selected for a closer inquiry. We coded all forms and degrees of transgressive or abusive behavior described in the material, including those that the interviewees themselves did not understand as such. For this study, we also selected quotes coded under the themes, digital working conditions’, ratings and relationships with customers. In analyzing these quotes, we searched for patterns and variations in the informants’ experiences and narratives in a mutually dynamic and exploratory process.

The quotes included in the analysis were purposefully selected for their capacity to illustrate how specific platform affordances shape the dynamics of harassment and abusive behaviours between customers and workers. Particular attention was given to identifying instances where digital affordances mediated or intensified these harmful interactions. In addition, the selection of quotes was guided by a commitment to capturing variation across different types of digital labor platforms and to reflecting experiences of both online and offline forms of harassment. This approach enabled a nuanced understanding of how technological and social factors intersect to produce vulnerability in platform-mediated work.

The rationale for the selection and scope of interview excerpts follows the principle of meaning saturation, as described by Hennink et al. [

50]. This concept refers to the point in qualitative analysis at which further data no longer reveals new nuances or interpretations. As outlined above, the analysis draws on the concept of ‘high-level affordances’[

34], which proved analytically useful to identify relevant types of high-level affordances across different types of digital labor platforms, and in turn trace how they co-produce harassment and abusive behavior in the context of PMW.

5. Analysis and Results

Based on this analytical approach, three high-level affordances [

34] were identified. These affordances resonate with keyways in which digital technologies mediate and structure interactions in PMW. Furthermore, they align with existing research highlighting how digital platforms facilitate meetings, connections, and communication between workers and costumers – often in ways that carry implications for power dynamics, boundary management, and exposure to risk within PMW [

51,

52] (Author 1).

5.1. The Three High-Level Affordances

The three high-level affordances identified are:

I) The capacity of digital platforms to transcend physical space (HLA-I: Transcending physical space)

II) The capacity of digital platforms of blurring boundaries between private and professional domains (HLA-II: Blurring boundaries)

III) The capacity of digital platforms to amplify asymmetric and unequal gendered, classed, and racial power relations between platform workers, their customers and the digital labor platforms (HLA-III: Amplifying asymmetric power relations).

In the following these three high-level affordances are substantiated in detail and related to the literature.

HLA-1 (Transcend Physical Space)

According to Heiland [

53], platform-mediated platform work is characterized by the ‘delocalization’ of work and the ‘altered spatial relations’ that digitalization brings with it. This affordance refers to the fact that digital labor platforms enable contact, interaction and relationships across spatial distances. That is, the platform facilitates the meeting between the interacting parties (e.g. platform workers and customers) regardless of the physical distance between them. This means that meetings facilitated by digital labor platforms can be close and intimate, but also non-committal and fleeting, since the spatial relations in PMW are multidimensional and changeable. The change in spatial relations in PMW means that platform workers can meet and interact with customers both online and offline, and that PMW often involves shifting ‘spatial relations’ depending on the work they do. This affordance is closely related to the next since multidimensional and changeable relations often entail boundarylessness.

HLA-II (Blurring Boundaries)

‘Boundarylessness’ [

54,

55] is the second high-level affordance that we identify as relevant. This affordance can be formulated as a border lessness in time and space, and the boundaries between work time and leisure time are dissolving. For example, many PMW tasks can be distributed, solved, evaluated, and paid without the worker needing to leave the computer. The ‘Boundarylessness’ also refers to the fact that digital platforms facilitate immediacy in interaction. This can create easy and fast communication, but it can also create expectations of workers to be available at all times of the day and night, regardless of local time (Author). This is the case for crowd workers who find and perform work online. This implies that work is entering the private sphere in new ways [

4] and that the boundaries between the private and the professional are changing and are constantly renegotiated [

54]. This invasion of privacy can exacerbate the negative consequences of harassment, as it becomes increasingly complex to close off the private sphere.

HLA-III Asymmetric Power Relations

The third high-level affordance identified as relevant is the unequal power relationship between the platform worker, the customer, and the digital platform that facilitates it. Unequal power relations have to do with the digital infrastructure of the digital labor platforms. Since platform owners are the primary creators of digital infrastructure, they have the privilege to define the digital conditions for platform workers’ presence on the platform [

56,

57]. For example, platform workers do not decide what should be displayed on their personal profile, such as the number of tasks completed, ratings, etc. [

58]. And the rating is not to be negotiated or removed. The digital infrastructure of the platform is crucial for enabling platform workers to communicate and make appointments with customers online. In GPS-based platform work, the platform determines which customers the courier meets around the city and how they can communicate. Digital platform infrastructures often prioritize customers on the platform over platform workers. This is conceptualized as ‘information asymmetries’ that skew power relations [

57] (p. 902). For example, on digital labor platforms, the ability of the platform worker to collect data about a customer is limited. In contrast, the data that the platform collects about the platform worker is far more extensive [

57]. Also, it is well documented that unequal power relations are crucial for the social and economic security of platform workers and the performance of their work [

8,

23,

24,

29,

56,

58,

59]. Van Doorn [

57] conceptualizes platform-mediated service work as ‘degraded labor’ and frames this work within a long distinctly gendered and racialized history (p. 900). The asymmetrical work and power hierarchies between workers, customers, and digital labor platforms can have impact on psychosocial stresses, including the risk of harassment and abusive acts in PMW. For example, asymmetrical power relations between platform workers and customers can heighten perceived pressure to comply with costumer demands, even when workers judge such compliance to be risky [

23,

60].

5.2. Analysis: The Shaping of Risks of Harassment and Abusive Behavior in Platform-Mediated Lo-Cation-Based Work

5.2.1. A Creeping Sense of Threat: The Capacity to Transcend Space

Digital labor platforms have the capacity to transcend physical space, and this capacity is shaping the risks of harassment and abusive behavior, in working situations where online relationships between workers and customers are taken into an offline environment. Contact with the customer in this transition between online and offline can involve loss of control and a feeling of vulnerability as space and physical distance change. In the interview, a young female platform worker who finds cleaning jobs on a digital labor platform says that she often feels unsafe when she is performing the cleaning tasks in the private homes of her customers.

There is some element of… me going into strangers’ houses. I don’t know who they are and what they have in their house. And sometimes you come across things that violate my boundaries a bit. Like opening a drawer filled with dirty sex toys. You know, something that is transgressive. It can be fun story to share. But I can’t help thinking a step further: ‘I wonder if my life would ever be in danger in this job? Often, it’s the women with low-status jobs who are victims of things because they don’t have status. (Young, female platform worker, performing cleaning mediated via a browser-based digital labor platform)

A common theme in interviews with female platform workers who provide platform-mediated cleaning and childcare in private homes is that they experience a particular risk associated with meeting customers in their homes. Meetings with the customer have typically been agreed upon and planned online, allowing the customer to hide behind the anonymity of the digital relationship. In principle, this digital mediation of work opens up the possibility for customers to provide false information about themselves online. While some platforms verify their users’ accounts by making it mandatory to submit either government issued ID, many other platforms do not require any verification whatsoever. The platform in question do not.

This experience of vulnerability is also shaped by the power dynamics between the platform worker and the customer, as well as the status and value ascribed to the work by the customer. How the platform worker deals with the creeping sense of threat and the blurred boundaries between customers’ (intimate and transgressive) private lives and her work is up to her. It is not something she even considers contacting the digital labor platform about. While the customer has access to data about the platform worker via her profile on the platform, the platform worker cannot know for sure who she is reaching out to [

58]. The unequal access to data in the platform-mediated relationships between customers and platform workers [

8] thus has an impact on the platform workers’ lack of perceived safety. Several of the female platform workers who clean or babysit in the homes of strangers talk about an uncertainty about whether the customer is actually who he/she claims to be:

I always check where they live. Sometimes I might even look them up on Facebook to see their pictures, for my own protection. I can’t actually see [on the platform] who is booking me. (Young, female, platform worker, performing cleaning tasks mediated via a digital labor platform)

Also, several of the platform workers explicitly consider the risk of harassment in their work to be related to the fact that they are in a working situation in which they are the vulnerable party in an unequal relationship, and that this vulnerability intersects with their gender, skin color, age or social class, and the digital mediation of working tasks. This concern is not insignificant, as international research literature on harassment and abusive behavior in PMW shows that young women are particularly vulnerable in PMW [

23,

61,

62,

63]. In this quote the high-level affordance of the platform produces uncertainty and anxiety that interacts with users’ gender, class and race.

5.2.2. ’That’s Where I Drew the Line’: The Capacity to Transcend Boundaries

Several of the female platform workers have experienced being booked for tasks in private homes, and when they arrived it was unclear what the intention behind the booking actually was. Several female platform workers report that they have turned down ‘loneliness bookings’, for example, a booking where it turned out that the father of the children supposedly being looked after was at home and had made dinner when the platform worker arrived at the address. Several female platform workers report that they have been offered (unwanted) gifts, dinners, or trips and that this can be experienced as transgressive and sometimes offensive:

(...) it was perhaps more a loneliness booking than it was a cleaning booking. It wasn’t so important with this cleaning. It was more important that I came, and I was going to get this gift and stuff. Yes, it was. I think that’s where I drew the line. (Young, female platform worker, performing cleaning mediated via a digital labor platform)

The platform worker perceives it as a transgressive act when the service the customer wants to buy turns out to be care, friendship, or a romantic or sexual relationship. Therefore, the platform workers in our material prefer the customer to be away from home when they arrive to do their work. It is a pattern in our material that the boundaries between the private and public lives of the platform worker and the customer are fluid [

54,

55], and that these boundaries are very often crossed and must be protected by the platform worker, online as well as offline:

It feels wrong to be contacted [by platform customers] on the various other social platforms and media profiles I have. As soon as something goes beyond this platform [digital labor platform] I feel... unsafe might be the wrong word, but it feels wrong. Last week a middle-aged man wrote to me on LinkedIn; ‘hey, I’ve booked you through [the platform] and just want to connect’. I don’t know what to do with it. (Young, female platform worker, performing cleaning mediated via a digital labor platform)

Setting and negotiating boundaries to feel safe appears to be an ongoing process that extends beyond both online and offline spaces, as well as different platforms within the online space [

15]. When a customer finds and contacts her on a social media platform that this platform worker uses in her personal life, it feels like a violation of her privacy. As an attempt to regain control she requested the labor platform to remove her family name from her profile. We do not know whether this strategy worked in her favor. On the other hand, from the parents’ view, the platform worker is a stranger whom they trust with their children. They might feel more secure through a connection on a social media platform. Thus, there seems to be a disconnection between the two parties’ interests stemming from the affordance of uncertainty of connecting through a digital platform. While the platform worker aims to maintain conventional boundaries between professional and personal domains, the parents want more connection due to the loose nature of their relationship with their babysitter.

5.2.3. ‘You Are a Bad Worker’: The Capacity to Amplify Asymmetric and Unequal Power Relationships

A young female platform worker talks about a very unpleasant experience with a customer when cleaning in the customer’s home:

(…) She [a customer] was always shouting: ‘Oh! You have to do like this. I can understand that she is an old lady. I was also saying: ‘Okay, just give me instructions. I will do it’. But after working two or three days, it was becoming really tough for me because she was always behind me: ‘Oh! Do like this’. ‘More energy, work fast, work fast. You work slow’. Always just shouting: ‘Oh, why did you do this? You are a bad worker. How do you work in other places? You do not know how to work’. It was painful. (Young, female platform worker of color, performing cleaning mediated via a digital labor platform)

This is one of the more extreme examples in our data material of customers who are staying in the home while the platform worker is cleaning. The platform worker explained the customer’s behavior by explaining that the customer and the platform worker have similar cultural backgrounds, where service workers like herself are treated as “a lower class”. Therefore, she did not confront the customer. Despite this explanation, she still addressed her experiences as “verbally abusive” acts. The data material includes examples of customers who are either overzealously checking the work or commenting on or shouting at the platform worker while cleaning. However, none of the platform workers in our material find that they are in a position to make any request or complaint to the customer or to the labor platform. In the example above, the platform worker responds to the customer politely and constructively. She protects herself by avoiding taking on more tasks from the customer. The labor platform, who are informed about the harassment, does not provide her with formal options to report abusive or inappropriate behavior so the incident can be recorded and prevented. On the contrary, the rating system of the digital platform affords platform workers not to cancel planned bookings and to adapt to the conditions to get good ratings. The platform worker in this example told that her former customer, after the episode, still offered cleaning tasks on the platform, now with a higher payment.

This quote exemplifies all three affordances. The platform’s transcendence of physical space isolates the worker from potential support structures, leaving her alone with an abusive customer. The blurred private-professional boundaries are evident as workplace harassment occurs in the customer’s home, where traditional workplace protections are absent. Most critically, the platform amplifies existing power asymmetries the customer’s age and class privilege combined with the worker’s economic vulnerability to enable sustained verbal abuse.

5.3. The Shaping of Risks of Harassment and Abusive Behavior in GPS-Based On-Demand Plat-Form-Mediated Work

Another young platform worker is associated with a GPS-based digital labor platform in Copenhagen. He works as a courier. He delivers food to private customers and receives assignments via the work platform’s app. He holds a temporary residence permit in Denmark and communicates with customers in English. He said that most of the customers and restaurant employees that he meets at his work are friendly. However, if something goes wrong during delivery, conflicts can arise. He told of one restaurant where the employees were very unpleasant with him:

They [restaurant employees, ed.] are very standoffish, very, very dismissive of you. They will, like, you will be like one meter away from them, like, looking them straight in the eye. It’s as if you’re not there. Yeah, you are a complete ghost. They will not acknowledge you. They will completely disregard you. (…) OK, but if you’re just like avoiding me… yeah, I don’t like that way of working. So, I try to avoid those restaurants as much as possible. (Courier associated with a GPS-based labor platform)

Several platform workers discuss experiences of being made invisible as a specific kind of offensive act. Several explain that the work they do is given such a low social status that they are treated with such distance or disrespect that the platform workers sometimes become completely invisible in the relationship with a customer. The customer sees their service, while the platform worker who is performing the service becomes invisible as a human being. Van Doorn [

57] argues that service workers are made invisible and interchangeable in the digital mediation of tasks. In this example, the courier is treated as invisible by the customer. This and the previous example call for attention to their social status as workers and the status of the work performed. The courier’s strategy is to avoid restaurants where they are dehumanized. The app only has a digital support function he can write to if he experiences something unpleasant. In some cases, platform workers can use informal digital meeting places such as Facebook groups, which several digital labor platforms facilitate [

64], for example, to warn each other about unpleasant customers. But beyond this, the labor platforms offer minimal options for the platform workers to protect themselves from abusive or harassing behavior from customers, which might increase the severity of cases. Another courier explains her options when customers get angry or behave in an abusive or inappropriate manner:

I cannot do anything else than to say to her: You should write to support; they should handle it. Yeah, that is also in the agreement, like - maybe not in the agreement - but in the recommendations [by the labor platform). Like, how should I communicate with customers? Of course, I cannot get into disagreements or fights and everything. I cannot argue. I just … like politely say you know: ‘Write to support, that this happened. Because they should handle such things. (Courier associated with a GPS-based labor platform)

All the platform workers we interviewed mentioned the digital support function as the one they turn to if they experience any trouble in their work. The support functions of different labor platforms work in various ways. But generally, it’s a feature where customers and platform workers can contact the platform in writing or verbally, and support staff respond to them. The speed and responsiveness of the platform vary between platforms [

64]. The platform worker in the quote above mentions that she “can’t start arguing”. The platform has advised her never to engage in conflict, but always to respond in a polite and disarming manner. In all our interviews with platform workers, they are advised never to engage in conflict, but to withdraw and refer to support. Several studies point out that the unequal power relationship between platforms, customer and platform worker means that the platform worker is the vulnerable part in the relationship with the customer [

8,

23,

24,

56,

59]. We see the above example as an example of how power relations in platform work influence the harassment that platform workers may experience, just as it influences how it is possible for the platform worker to defend themselves against harassing or abusive behavior. It will typically be the platform worker who, in connection with harassing or abusive relationships with the customer, will have to withdraw and accommodate the customer’s needs, with the help of the platform’s support function and the platform’s instructions on individual conflict management.

5.4. The Shaping of Risks of Harassment and Abusive Behavior in Online (Web-Based) Plat-Form-Mediated Work

A young man with a bachelor’s degree in international trade and marketing works part-time as a freelancer via an international digital labor platform. He works as a translator and is paid per word. All his tasks are agreed, delivered, and paid for online. In the quote, he describes his latest task, where he has been assigned to translate 1,000 words per month for the customer he refers to.

It’s very rare that people are directly unpleasant... People are just generally impatient when hiring freelancers. It’s like; ‘Is it possible to finish the job already? Please send me a short message. How far is the project?’. (...) But I’m at a point where if I get fired from a job, I don’t care (laughs). At least with this guy [a client], because it’s so poorly paid anyway. But he can guarantee a certain number of words per month [for translation], and that gives me a certain safety net. So, I know that I can at least earn something every month to cover some of my costs. That’s why I put up with him being a jerk. (Freelancer associated with a web-based digital labor platform)

The freelancer emphasizes that he rarely encounters unpleasant customers. However, he describes that platform-mediated freelancing often involves impatient customers messaging him via the platform, pushing him to complete tasks faster. The possibility of immediate, direct contact through the platform increases the scope for potential conflict and pressure in relation to the pace of task completion. He describes that his way of dealing with such customers is strategically aligned with the importance of the task to his earnings. The platform-mediated relation is described as a financial transaction that he can reject, if he has the economic space to do so. Another young freelancer who has a university degree works full-time via a digital labor platform used primarily by skilled or highly specialized freelancers. Most of her tasks are agreed, delivered, and paid online. She describes an incident where she was hired for a small communication task. The platform worker says that she goes the extra mile with the task because the client has a professional network that the platform worker would like to access. However, when the job is delivered and the invoice is to be paid, the customer gets angry and accuses the platform worker of not delivering the job:

He was really angry. He was like, ‘well, I can’t recommend you to anyone if you don’t do it! And if it’s so expensive!’ And you know: It was a much lower price than what I normally charge. (Freelancer associated with a web-based digital labor platform)

The platform worker emphasizes that she did not experience the situation as abusive, but rather that it

“for some could be perceived as transgressive”. The customer threatened to undermine the platform worker’s reputation in his network and possibly also tried to avoid paying the invoice. This is an example of how customers on digital platforms can take advantage of the fact that platform workers are dependent on a positive reputation or positive ratings to access work. And that unequal power relations can be exploited to pressure, threaten, or violate the platform worker [

23,

60]. Also, some platforms permit their customers to reject completed work, thus avoiding paying, and still, platforms refuse to get involved in any disputes [

8] (p. 8). Like all the other examples in this article, the platform worker neatly avoids getting into conflict with the customer; she is polite and backs off. The platform worker proves to the customer that she is right, but she does not address the customer’s threat. In this case, the platform worker has the professional and personal resources to reject the customer and to demand her rights, but this is far from always the case. Like most platform workers, she does not have any professional or organizational support to help her deal with such situations (Author 1).

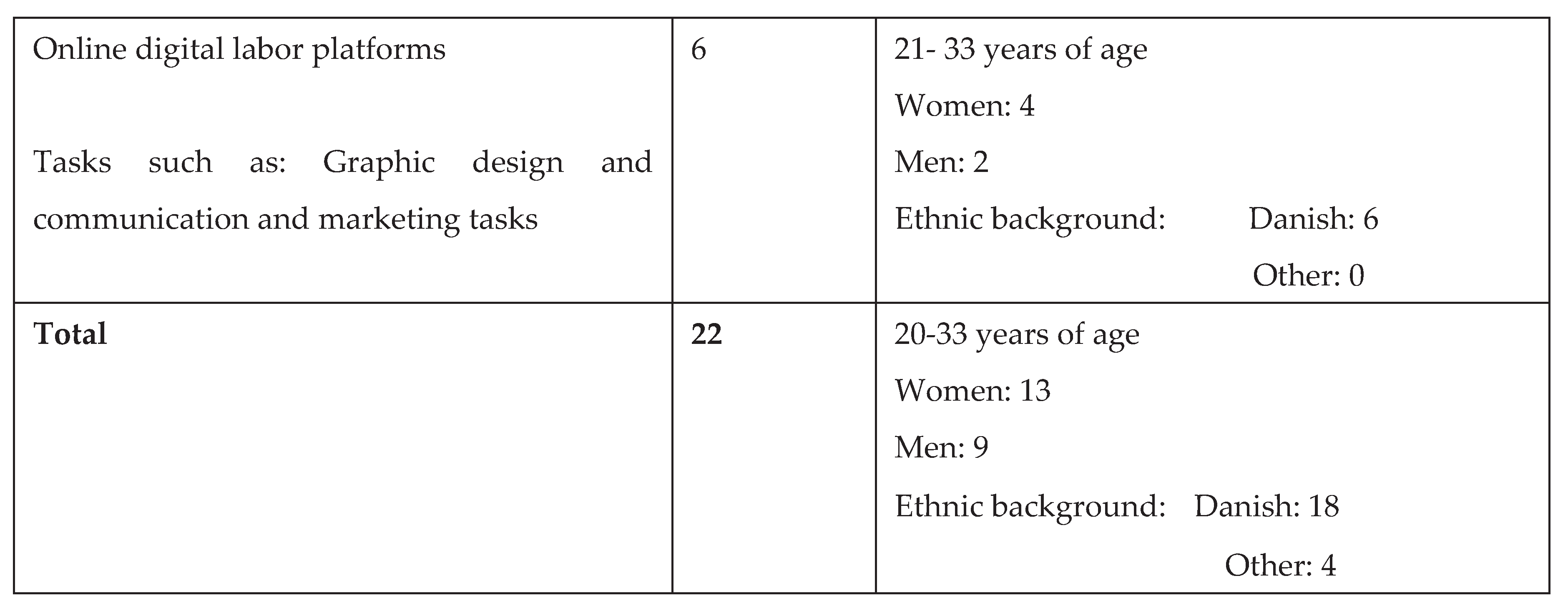

In the table below, we summarize the insights gained from the analyses in relation to how the three high-level affordances shape the relations between platform workers, their customers and digital labor platforms, and accordingly how this is shaping risks of harassment and abuse.

Table 2.

shows how the three high-level affordances have the capacity to shape relations between platform workers, their customers and the digital labor platforms.

Table 2.

shows how the three high-level affordances have the capacity to shape relations between platform workers, their customers and the digital labor platforms.

| Types of high-level affordance. |

Location-based (browser-mediated) labor platforms |

GPS-based, on-demand labor platforms |

Online (web-based) labor platforms |

| The capacity to transcend physical space |

Enable platform workers to interact with customers online and offline, intersecting with risks of false customer information, reduced control, and vulnerability during physical encounters. |

Enable workers to engage in numerous brief, shifting interactions offline, involving both customers and individuals encountered in public spaces. |

Enable workers to interact with customers online, across diverse, shifting relationships varying in duration (short or long-term) and scope (national or global). |

| The capacity of blurring boundaries between private and professional domains |

Interactions take place in domestic or liminal spaces, blurring “on/off duty” boundaries, complicating misconduct refusal, and enabling unwanted customer interactions that violate workers’ privacy across platforms. |

Interactions take place in domestic or liminal spaces, blurring “on/off duty” cues, complicating refusal of misconduct; platforms seldom assist workers with managing intimate customer boundaries. |

Negotiating customer interactions crosses multiple online platforms, enabling customers to reach workers through personal channels, complicating control and increasing perceived privacy violations. |

| The capacity of amplifying asymmetric and unequal power relations between platform workers, their customers and the labor platforms. |

Workers become interchangeable through low customer identifiability and high transaction volume, tend to normalizing disrespect (‘humans-as-a-service’). Customer ratings discourage cancellations, fostering compliance and limited customer accountability. |

Low identifiability and high transaction volume render workers interchangeable, tending to normalize disrespect (‘humans-as-a-service’); ratings pressure worker compliance, enabling customers to avoid social consequences. |

Depending on how specialized the tasks are, workers become interchangeable.

The possibility of immediate, direct contact increases the scope for potential conflict and pressure in relation to the pace of task completion.

Demanding one’s rights depend on financial and personal resources. |

6. Discussion

This study identified three high-level affordances characteristic across the types of PMW explored. However, the significance of these high-level affordances depends on the business models of the labor platform and on the work being performed. For some platform workers, every aspect of their job is facilitated through a platform; for instance, couriers who use GPS-based work applications. For others, particularly those in location-based tasks, only certain aspects of the workflow (e.g., task assignment and customer evaluation) are governed by the platform’s algorithms. The types of customer relationships encountered by platform workers are diverse. Consequently, the three identified high-level affordances shaping the risks of harassment and abusive behavior differ in salience across distinct forms of PMW.

In this study, high-level affordances provide the primary analytical lens for examining how platform affordances shape risks of harassment and abuse in PMW. Rather than treating digital platforms as mere static and technical bundles of features, the study investigated how high-level affordances embedded in platform designs and the wider platform environment shape platform workers’ encounters with customers and, in turn, affect platform workers’ exposure to risks of harassment and abusive behavior.

The result of the present paper resonates with Prassl’s [

8] critique that digital-platform workers are being rendered “humans-as-a-service”. Our findings show that this dynamic is not a separate affordance but a manifestation of HLA-III (power asymmetry), i.e., the platform’s capacity, through various mechanisms, to amplify asymmetric, gendered, classed, and racialized power relations between customers and platform workers. When a platform promises rapid, low-cost service delivered by an abundant, instantly replaceable workforce, it normalizes de-humanization and weakens reciprocity, thereby inclining customers to disregard basic respect and human dignity. Under such asymmetry, harassment often becomes more severe because customers can leverage ratings and threats of deactivation, and amplified by platform visibility and persistence, to coerce compliance, escalate from incivility to abuse, and do so with limited accountability. The consequences are predictable from a safety perspective: heightened vulnerability to harassment, intensified pressure to accept unfavorable conditions, and narrowed scope for resistance.

Empirically, we observe customers treating workers as mere service functions - rendering the individual redundant, indifferent, or effectively invisible. We classify these dehumanizing interactions as harassment and abuse. Our analysis indicates that the likelihood of such behavior in PMW is structural rather than discretionary, and scales with workers perceived replaceability and position within a social hierarchy, and it intersects with age, gender, ethnicity and race.

Moreover, this HLA-III (power-asymmetry) interacts with other high-level affordances, which together shaping the overall risk of harassment and abuse in PMW. Because high-level affordances are fluid, distributed, and partially opaque, maintaining safe and healthy working conditions in the platform economy is inherently more challenging: the constraints are neither as stable nor as transparent as those that govern an industrial plant or traditional workplaces. Safety science must therefore add to its traditional focus on system invariants with tools for analyzing algorithmic coupling and the relational dynamics that shape platform workers’ risk landscape, to counter the adverse effects of PMW on abusive behaviors and harassment of platform workers. Recognizing the distinction between low-level and high-level affordances clarifies why interface ‘make-up’ alone, such as providing a panic button, cannot remedy issues such as harassment or abuse: the basic mechanisms reside in the platform’s high-level affordance structure, not in its low-level controls. This reframing clarifies where effective interventions must act; on the high-level affordance structure that configures everyday interactions and increases risks of harassment and abuse.

In PMW, harassment or abusive behavior are not merely transient experiences. Rather, when workers experience such incidents and lack the opportunity to debrief, seek support, or report them to colleagues or platform management, they may have long-term implications for the worker’s health and well-being. Irrespective of how we classify the harassing or abusive acts that platform workers experience in their jobs, their prevalence warrants serious attention. Occupational

-health research consistently links workplace harassment, bullying, threats and violence to increased risks of common mental disorders [

65,

66,

67], prolonged sickness absence [

68] and, in severe cases, suicidal behavior [

69,

70].

A defining feature of PMW is the attenuation of social and organizational support, as most platform workers operate alone, lack a collegial network, rely on asynchronous, app-mediated communication governed by an algorithmic system. These conditions constrain restorative responses after harmful encounters, thereby amplifying the health impact of harassment and abuse in PMW.

6.1. Strength and Limitations

This study relies on qualitative evidence, drawn from semi-structured interviews with platform workers and workshops that engaged several digital-platform stakeholders. While this approach yields rich, contextual insights and allows in-depth exploration of complex OHS-related issues, it is inherently constrained by the limited sample of platforms and platform workers willing to participate, within each of the three types of platforms explored. Certain dimensions of PMW may therefore not be captured by the present analysis. Thus, the qualitative analyses undertaken do not provide knowledge on the prevalence of harassment among platform workers and thus cannot indicate how widespread the observed forms of harassment and abuse are. Instead, the study’s primary objective is to elucidate the type of high-level affordances and the related mechanisms through which specific platform affordances may heighten the risk of harassment and abuse.

To bolster the credibility of the findings, we convened stakeholder workshops that included worker representatives and platform owners. These sessions served as opportunities for triangulation and face

-validity checks, enabling participants to verify interpretations and to surface divergent viewpoints. Identifying and convening relevant stakeholders is notoriously difficult in this domain, as platform firms rarely belong to employer federations and most platform workers are not unionized. The study’s success in organizing and conducting three workshops with such dispersed actors, therefore, represents a notable methodological strength, and they helped offset the limited number of interviewees by allowing broader debate of emerging themes. Comparable participatory validation strategies are well

-established in occupational safety and digital labor research [

71,

72].

In addition, platform workers’ socio-economic circumstances vary greatly. While the work is the only access to income for some platform workers, it is supplementary to primary employment for others. Although this relationship is not examined in detail in this study, previous studies show that platform workers’ vulnerability is closely related to their degree of economic dependence on platform earnings [

52,

56] (Author). Consequently, further work should therefore, to a higher extent than possible in this study, disaggregate harassment risk profiles by income dependence as well as by age, gender and race, to support the validity of the findings presented.

7. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study provides the first systematic analysis on how platform affordances shape the types and severity of harassment and abusive behavior in platform-mediated work (PMW). We identified three high-level affordances that structure the risk of harassment and abuse: a) spatial transcendence - the platforms’ capacity to transcend physical spaces; b) Boundary blurring - the capacity of platforms to blurring private - professional domains; and c) Power-asymmetry amplification - the capacity of platform infrastructures to amplify gendered, classed, and racialized power asymmetries among platform workers, customers and the platform itself.

All three affordances shape and increase the risk of harassment and abuse, but their relative significance varies depending on the type of platform (e.g., location-based versus online/on-demand marketplaces). This platform sensitivity is essential for both analysis and preventive actions.

Accordingly, prevention strategies must be platform-specific and address the relational dynamics embedded in platform business models. At the policy level, this implies regulative frameworks - national and cross-border - that recognize and constrain harmful affordance structures and thus enhancing protection of platform workers. At the platform level, illustrative controls might include client vetting or background checks on customers, where possible, and deploying panic/emergency features for location-based works; for online/on-demand settings, effective measures might include platform-side moderated communication channels, delayed or abuse-resistant rating or review systems, and greater algorithmic transparency and auditability.

Crucially, high-level affordances are not merely theoretical; they constitute latent structural features that shape and organize interactions among workers, customers, algorithms and platform governance. Our empirical results show that these affordances actively co-produce, trajectories, and consequences of harassment. Effective mitigation therefore requires design and policy interventions beyond interface tweaks, aimed at the underlying relational dynamics and managerial logics of platform environments. Further multi-method research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to assess the generalizability of the identified three types of high-level affordances and associated mechanisms, to quantify the prevalence and severity of harassment in different segments of platform-mediated work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.N, L.Y.N. and J.D.; methodology, M.L.N, J.D.; formal analysis, M.L.N, L.Y.N. and J.D.; investigation, M.L.N, L.Y.N..; resources, M.L.N, L.Y.N. and J.D.; data curation, M.L.N, L.Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.N, L.Y.N. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, M.L.N, L.Y.N. and J.D; project administration, M.L.N.; funding acquisition, M.L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Danish Working Environment Fond under Grant 54-2020-09 20205100740

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMW |

Platform-mediated work |

| OHS |

Occupational health and safety |

| AM |

Algorithmic Management |

| KTE |

‘Knowledge Transfer and Exchange’ |

References

-

Duggan, J.; Sherman, U.; Carbery, R.; McDonnell, A. Algorithmic management and app‐work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Human Resource Management Journal 2019. . [CrossRef]

-

Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T. Health, safety, and well-being in platform-mediated work–a job demands and resources perspective. Safety science 2023, 163, 106130. .

-

Koutsimpogiorgos, N.; Van Slageren, J.; Herrmann, A.M.; Frenken, K. Conceptualizing the gig economy and its regulatory problems. Policy & Internet 2020, 12, 525-545. .

-

Wood, A.J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work, Employment and Society 2019, 33, 56-75. . [CrossRef]

-

Council, E. Infographic - Spotlight on digital platform workers in the EU. 2023. . Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/platform-work-eu/ (accessed on 27.3.2024 ). .

-

Moore, P.V.; Joyce, S. Black box or hidden abode? The expansion and exposure of platform work managerialism. Review of International Political Economy 2020, 27, 926-948. .

-

Jarrahi, M.H.; Sutherland, W. Algorithmic Management and Algorithmic Competencies: Understanding and Appropriating Algorithms in Gig Work. In Information in Contemporary Society, Taylor, N.G., Christian-Lamb, C., Martin, M.H., Nardi, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Volume 11420, pp. 578-589. .

-

Prassl, J. Humans as a service: The promise and perils of work in the gig economy; Oxford University Press: 2018. .

-

Todolí-Signes, A. The ‘gig economy’: employee, self-employed or the need for a special employment regulation? Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 2017, 23, 193-205. . [CrossRef]

-

Gregg, M. Part-time Precarity. In Work’s Intimacy; Polity Press: Cambridge, 2011. .

-

Wood, A.J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work, Employment and Society 2018, 095001701878561. . [CrossRef]

-

Liu, Y.-L.; Cheng, Y.; Tsai, P.-H.; Yang, Y.-C.; Li, Y.-C.; Cheng, W.-J. Psychosocial work conditions and health status of digital platform workers in Taiwan: A mixed method study. Safety Science 2025, 182, 106722. .

-

Gibson, J.J. The ecological approach to visual perception. Psychology Press 1979. .

-

(ILO), I.L.O. Information System on International Labour Standards: Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190). . Available online: (accessed on [14.07.23]). .

-

Rasmussen, P.K.B.; Søndergaard, D.M. Traveling imagery: Young people’s sexualized digital practices.MedieKultur: Journal of media and communication research 2020, 36, 076-099. .

-

Jesnes, K.; Øistad, B.S.; Alsos, K.; Nesheim, T. Aktører og arbeid i delingsøkonomien; 2016:23; FAFO: Oslo, 2016 2016. .

-

Huws, U.; Spencer, N.; Joyce, S. Crowd work in Europe: Preliminary results from a survey in the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. 2016. .

-

Garben, S. Protecting Workers in the Online Platform Economy: An overview of regulatory and policy developments in the EU; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017, 2017 2017. .

-

Huws, U. Online labour exchanges, or ‘crowdsourcing’: Implications for occupational safety and health: Review article on the future of work; European Occupational Safety and Health Agency: 2015/11/01/ 2015. .

-

Lee, M.K.; Kusbit, D.; Metsky, E.; Dabbish, L. Working with Machines: The Impact of Algorithmic and Data-Driven Management on Human Workers. In Proceedings of the the 33rd Annual ACM Conference, 2015, 2015; pp. 1603-1612. .

-

Gregory, K. ‘My life is more valuable than this’: Understanding risk among on-demand food couriers in Edinburgh. Work, Employment and Society 2021, 35, 316-331. .

-

De Stefano, V.; Durri, I.; Stylogiannis, C.; Wouters, M. “ System needs update”: Upgrading protection against cyberbullying and ICT-enabled violence and harassment in the world of work; ILO Working Paper: 2020. .

-

Moore, P.V. The threat of physical and psychosocial violence and harassment in digitalized work; International Labour Office Geneva: 2018. .

-

Chen, J.Y. Thrown under the bus and outrunning it! The logic of Didi and taxi drivers’ labour and activism in the on-demand economy. New Media & Society 2018, 20, 2691-2711. .

-

Alacovska, A.; Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C. Algorithmic Paranoia: Gig Workers’ Affective Experience of Abusive Algorithmic Management. New Technology, Work and Employment 2024. .

-

Rosenblat, A.; Levy, K.E.; Barocas, S.; Hwang, T. Discriminating tastes: Uber’s customer ratings as vehicles for workplace discrimination. Policy & Internet 2017, 9, 256-279. .

-

Stringhi, E. Addressing gendered affordances of the platform economy: The case of UpWork. Internet Policy Review 2022, 11, 1-28. .

-

Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T.; Almklov, P.G. Splintered structures and workers without a workplace: How should safety science address the fragmentation of organizations? Safety Science 2022, 148, 105644. . [CrossRef]

-

Shapiro, A. Between autonomy and control: Strategies of arbitrage in the “on-demand” economy. New Media & Society 2018, 20, 2954-2971. . [CrossRef]

-

Jarrahi, M.H.; Sutherland, W.; Nelson, S.B.; Sawyer, S. Platformic Management, Boundary Resources for Gig Work, and Worker Autonomy. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 2020, 29, 153-189. . [CrossRef]

-

Sloth Laursen, C.; Nielsen, M.L.; Dyreborg, J. Young Workers on Digital Labor Platforms: Uncovering the Double Autonomy Paradox. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 2021, 0. . [CrossRef]

-

Salmon, P.M.; Bhawana, K.; Irwin, B.G.; Brennan, C.J.; Read, G.J. What influences gig economy delivery rider behaviour and safety? A systems analysis. Safety science 2023, 166, 106263. .

-

Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Safety Science 1997, 27, 183-213. .

-

Bucher, T. If...then: algorithmic power and politics; Oxford University Press: New York, 2018; p. 1. .

-

Vicente, K.J.; Rasmussen, J. Ecological interface design: Theoretical foundations. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 1992, 22, 589-606. .

-

Albrechtsen, H.; Andersen, H.H.; Bødker, S.; Pejtersen, A.M. Affordances in activity theory and cognitive systems engineering. 2001. .

-

Vicente, K.J. Cognitive work analysis: Toward safe, productive, and healthy computer-based work; CRC press: 1999. .

-

Van Eerd, D., Saunders, R. Integrated knowledge transfer and exchange: An organizational approach for stakeholder engagement and communications. Scholarly and Research Communication 2017, 8. .

-

Gensby, U.; Van Eerd, D.; Amick, B.C.; Limborg, H.J.; Dyreborg, J. Knowledge transfer and exchange through interactive research: a new approach for supporting evidence-informed occupational health and safety (OHS) practice.International Journal of Workplace Health Management 2023, 16, 137-144. .

-

Dyreborg, J.; Gensby, U.; Limborg, H.-J.; Pedersen, F. Fra forskning til praksis i forebyggelsen af arbejdsulykker - R2P-projektet; Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Arbejdsmiljø og Team Arbejdsliv: København, 2020. .

-

Gensby, U.; Limborg, H.J.; Dyreborg, J.; Bengtsen, E.; Malmros, P.Å. Mobilisering af forskningsbaseret viden om arbejdsmiljø. Bedre sammenhæng mellem forskning og praksis, 1. udgave 2019 ed.; Copenhagen, 2019. .

-

Lavis, J.N.; Robertson, D.; Woodside, J.M.; McLeod, C.B.; Abelson, J. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q 2003, 81, 221-248, 171-172. .

-

Reardon, R.; Lavis, J.; Gibson, J. From Research to Practice: A knowledge transfer planning guide; Institute for Work & Health: Toronto, Ontario, 2006. .

-

Anna Franciska Einersen, J.K., Sara Louise Muhr, Ana Maria Munar, Eva Sophia; Plotnikof, M.M. Sexism in Danish Higher Education and Research: Understanding, Exploring, Acting; Not applicable: Copenhagen, March 2021, 2021; Volume Draft version. .

-

Järvinen, M.; Mik-Meyer, N. Kvalitative metoder i et interaktionistisk perspektiv; Järvinen, M., Mik-Meyer, N., Eds.; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, 2005. .

-

Staunæs, D.; Søndergaard, D.M. Interview i en tangotid. Kvalitative metoder i et interaktionistisk perspektiv. Interview, observation og dokumenter; Hans Reizels Forlag: 2005. .

-

Jones, C.; Trott, V.; Wright, S. Sluts and soyboys: MGTOW and the production of misogynistic online harassment. New Media & Society 2020, 22, 1903-1921. .

-

Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77-101. . [CrossRef]

-

Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be (com) ing a knowing researcher. International journal of transgender health 2023, 24, 1-6. .

-

Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qualitative health research 2017, 27, 591-608. .

-

Nilsen, M. Health, Safety, and Working Conditions in Platform-Mediated Work: a Multilevel Perspective. Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, 2023. .

-

Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T. Health, Safety, and Well-Being in Platform-Mediated Work – A Job Demands and Resources Perspective. Safety Science 2023, 163, 106130. . [CrossRef]

-

Heiland, H. Controlling space, controlling labour? Contested space in food delivery gig work. New Technology, Work and Employment 2021, 36, 1-16. . [CrossRef]

-

Gregg, M. Work’s intimacy Cambridge, Polity Press 2011. .

-

Tenório, N.; Bjørn, P. Online harassment in the workplace: The role of technology in labour law disputes. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 2019, 28, 293-315. .

-

Rosenblat, A.; Stark, L. Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: A case study of Uber’s drivers. International Journal of Communication 2016, 10, 27. .

-

van Doorn, N. Platform labor: on the gendered and racialized exploitation of low-income service work in the ‘on-demand’ economy. Information, Communication & Society 2017, 20, 898-914. . [CrossRef]

-

Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Dunn, M.; Nelson, S.B. Work precarity and gig literacies in online freelancing. Work, Employment and Society 2020, 34, 457-475. .

-

Franke, M.; Pulignano, V. Connecting at the edge: Cycles of commodification and labour control within food delivery platform work in Belgium. New Technology, Work and Employment 2021. .

-

Ravenelle, A.J. Hustle and gig: Struggling and surviving in the sharing economy; University of California Press: 2019. .

-

Banet-Weiser, S. Popular misogyny: A zeitgeist. Culture digitally 2015, 21, 152-156. .

-

Banet-Weiser, S.; Miltner, K.M. # MasculinitySoFragile: Culture, structure, and networked misogyny. Feminist media studies 2016, 16, 171-174. .

-

Cowling, M. Harassment Falls but Takes New Forms to Put Young Workers Most at Risk. People Management 2007, 13, 46. .

-

Gjetting, K.K.; Terkelsen, K.D.; Hansen, S.S.; Floros, K. Det usynlige menneske i platformsarbejde-en kvalitativ undersøgelse af algoritmisk ledelse. Tidsskrift for Arbejdsliv 2022, 24, 28-42. .

-

Rugulies, R.; Madsen, I.E.; Hjarsbech, P.U.; Hogh, A.; Borg, V.; Carneiro, I.G.; Aust, B. Bullying at work and onset of a major depressive episode among Danish female eldercare workers. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 2012, 218-227. .

-

Rugulies, R.; Sørensen, K.; Aldrich, P.T.; Folker, A.P.; Friborg, M.K.; Kjær, S.; Nielsen, M.B.D.; Sørensen, J.K.; Madsen, I.E. Onset of workplace sexual harassment and subsequent depressive symptoms and incident depressive disorder in the Danish workforce. Journal of affective disorders 2020, 277, 21-29. .

-

Clausen, T.; Rugulies, R.; Li, J. Workplace discrimination and onset of depressive disorders in the Danish workforce: a prospective study.Journal of affective disorders 2022, 319, 79-82. .

-

Bruun, J.E.; Dalsager, L.; Nordentoft, M.; Framke, E.; Madsen, I.; Sørensen, J.K.; Sørensen, K.; Rugulies, R. Det psykosociale arbejdsmiljø og risikoen for diabetes, sygefravær og førtidspensionering blandt lønmodtagere i Danmark (PSA-DISPO). 2022. .

-

Conway, P.M.; Erlangsen, A.; Grynderup, M.B.; Clausen, T.; Rugulies, R.; Bjorner, J.B.; Burr, H.; Francioli, L.; Garde, A.H.; Hansen, Å.M. Workplace bullying and risk of suicide and suicide attempts: A register-based prospective cohort study of 98 330 participants in Denmark. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 2022, 48, 425. .

-

Hanson, L.L.M.; Pentti, J.; Nordentoft, M.; Xu, T.; Rugulies, R.; Madsen, I.E.; Conway, P.M.; Westerlund, H.; Vahtera, J.; Ervasti, J. Association of workplace violence and bullying with later suicide risk: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of published data. The Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e494-e503. .

-

Flick, U. Doing triangulation and mixed methods. 2018. .

-

Blaikie, N. Approaches to social enquiry: Advancing knowledge; Polity: 2007. .

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |