Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of literature

2.1. Green Technology Innovation and CO2 Emissions

2.2. Renewable Energy Consumption and CO2 Emissions

2.3. Environmental Tax and CO2 Emissions

2.4. Gap in Literature

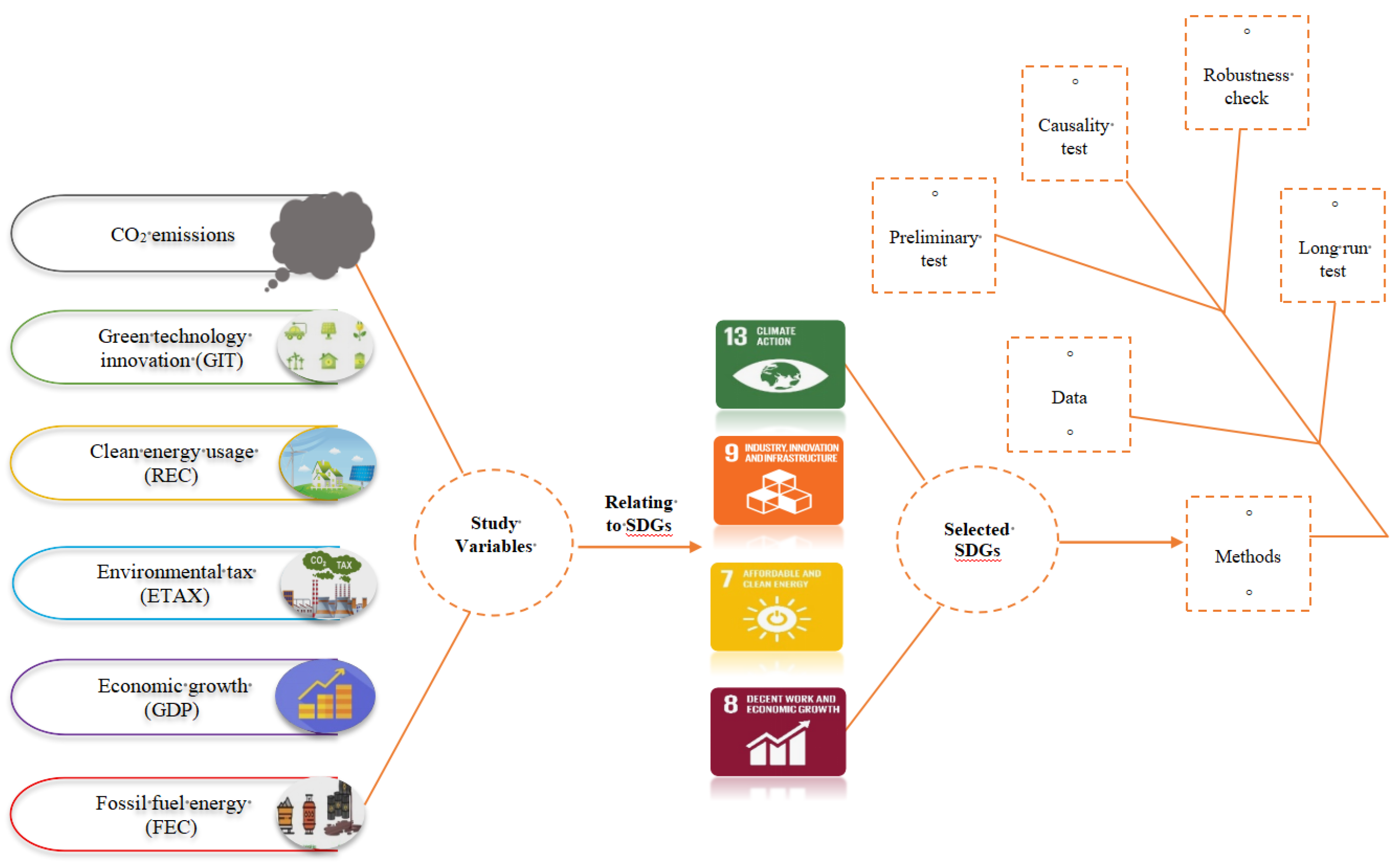

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Rationale and Empirical Model Building

3.2. Estimation Approach

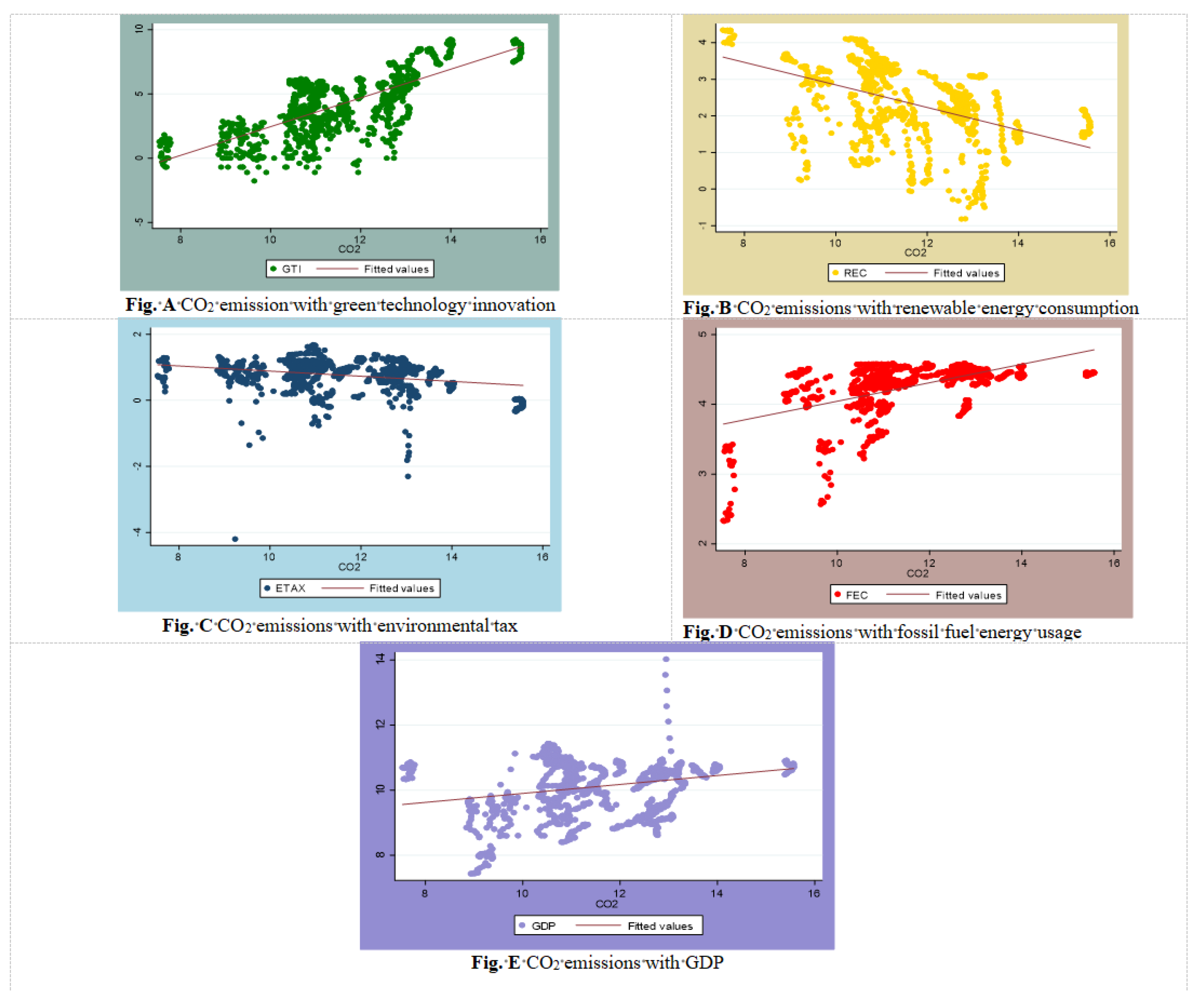

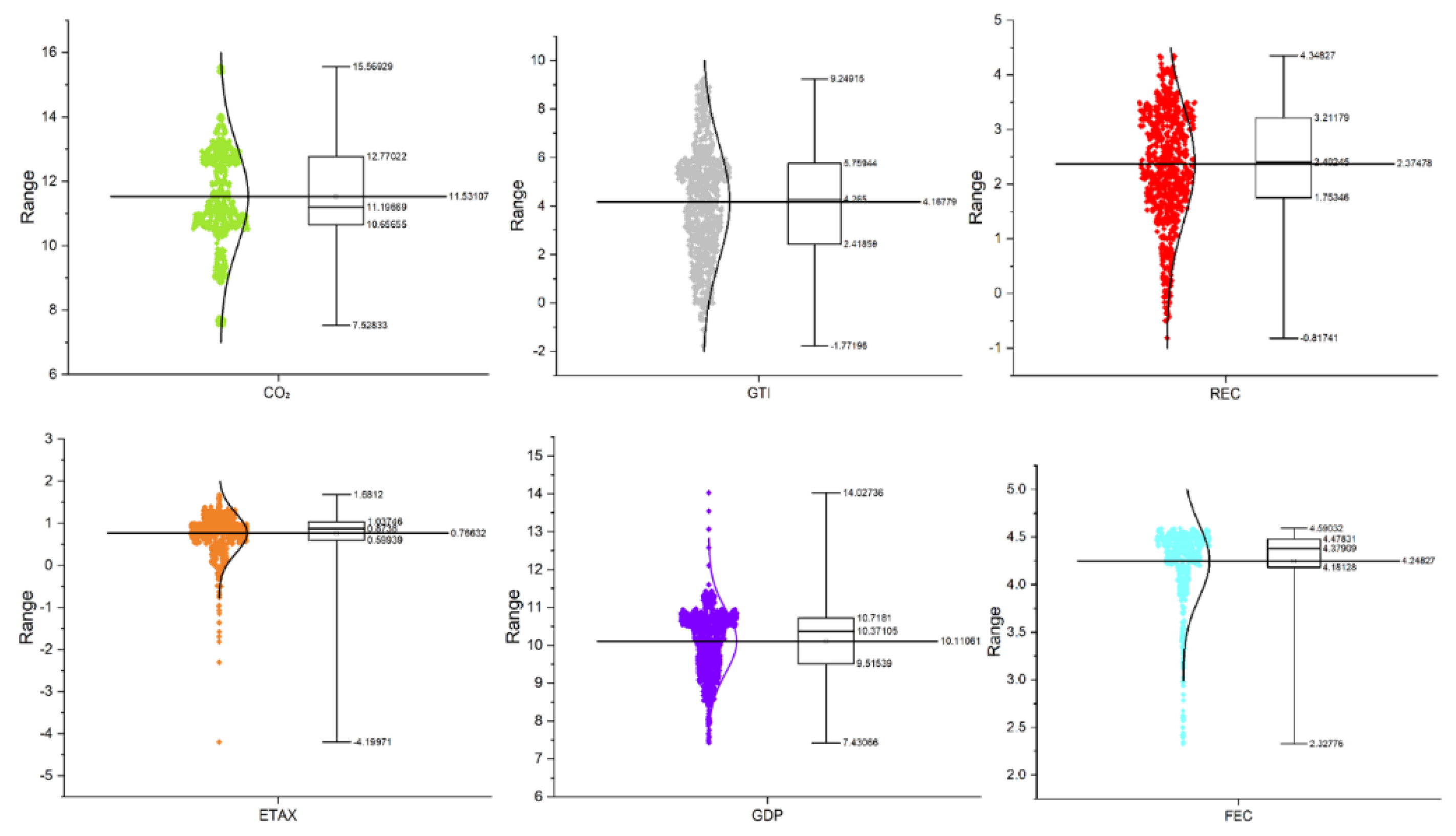

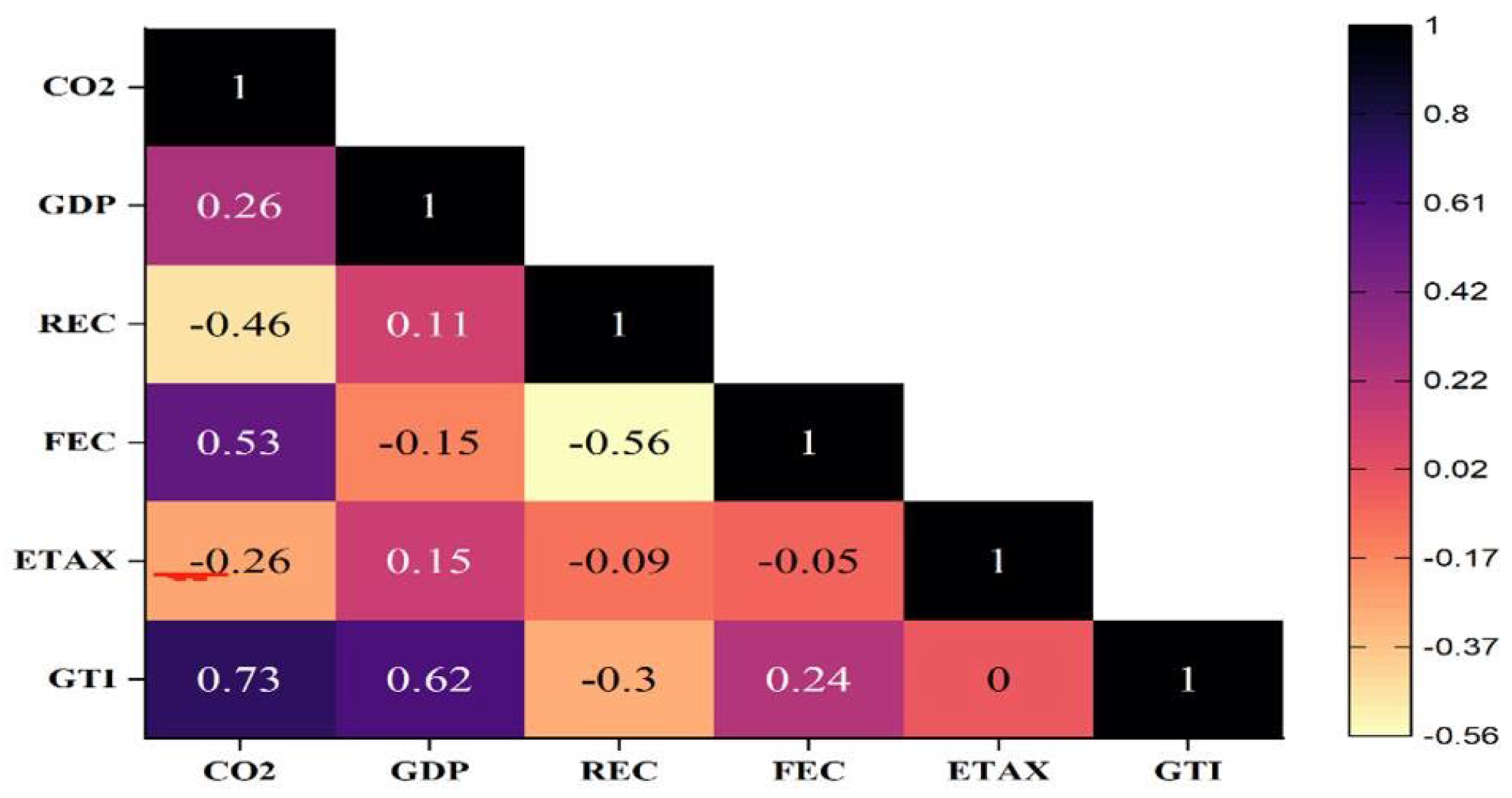

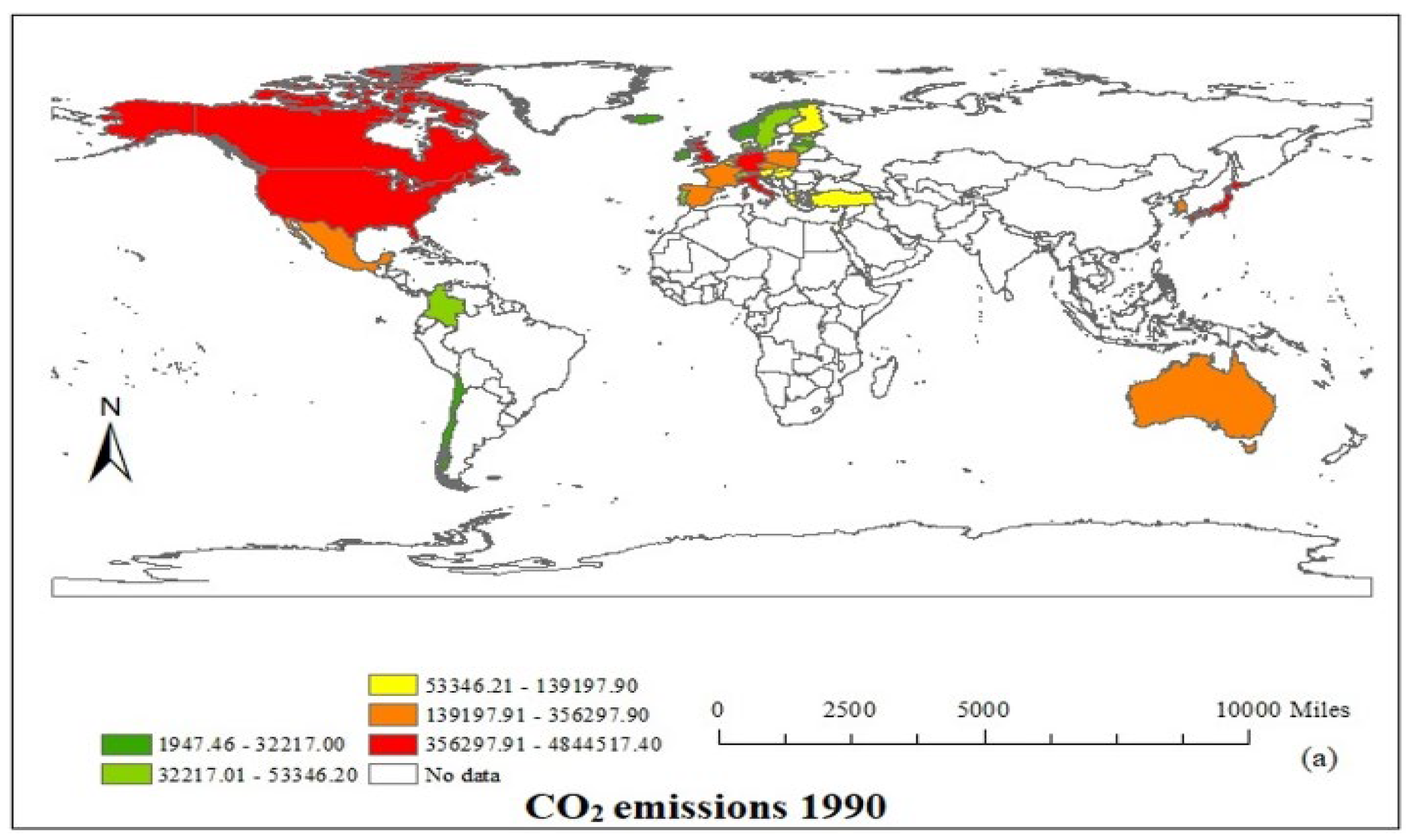

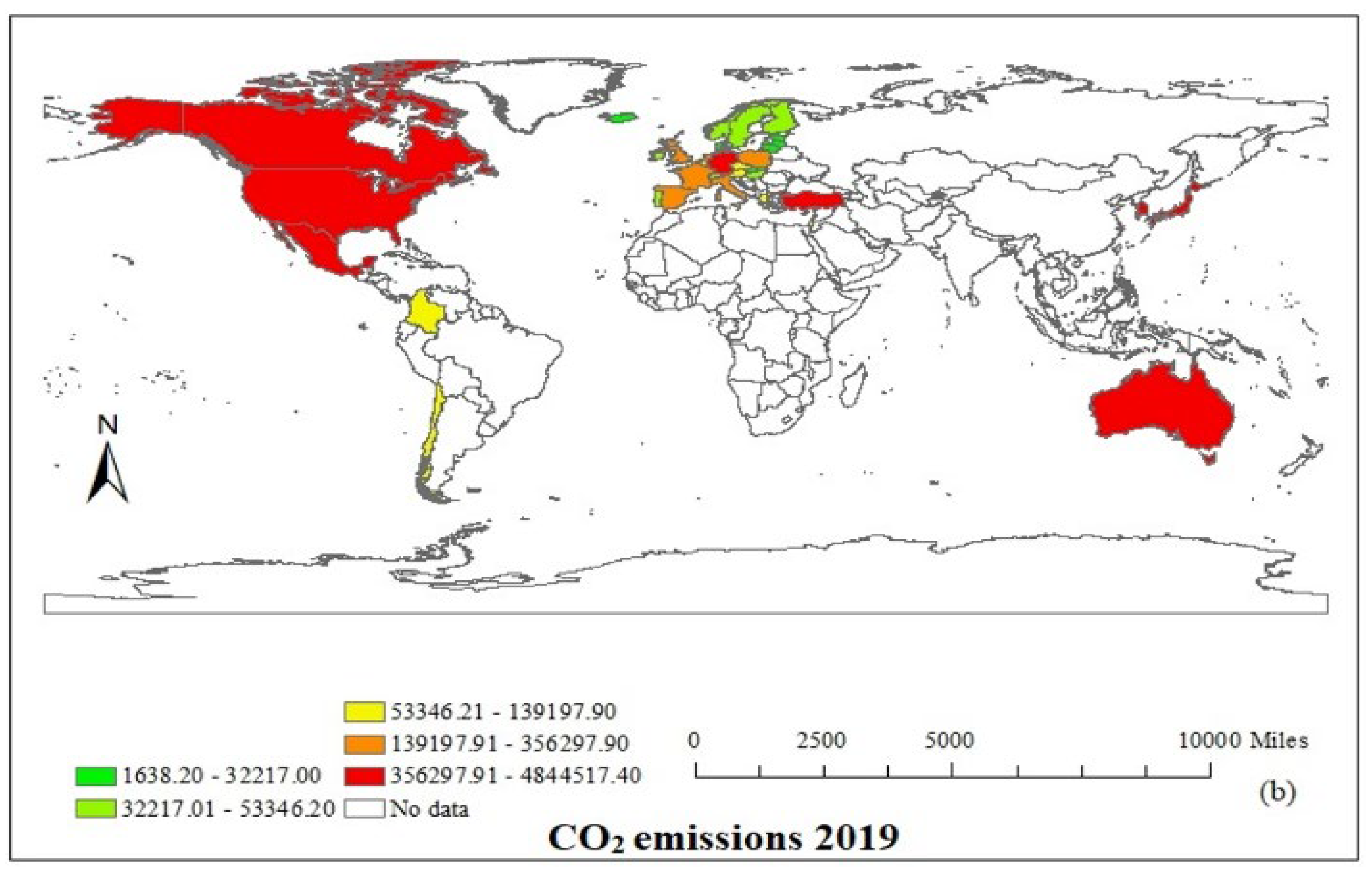

3.3. Data and Descriptive Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Long Run Estimation Results

4.3. Causality Test

5. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical approval

Informed consent

Data availability

Competing interests

References

- Zeng, S.; Li, T.; Wu, S.; Gao, W.; Li, G. Does green technology progress have a significant impact on carbon dioxide emissions? Energy Econ. 2024, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. (2022). “Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2022 “, accessed 01.03. https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Aug/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2022.

- Hassan, Q.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Mounich, K.; Algburi, S.; Jaszczur, M.; Telba, A.A.; Viktor, P.; Awwad, E.M.; Ahsan, M.; Ali, B.M.; et al. RETRACTED: Enhancing smart grid integrated renewable distributed generation capacities: Implications for sustainable energy transformation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2024, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobande, O.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ogbeifun, L. Repositioning green policy and green innovations for energy transition and net zero target: New evidence and policy actions. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Taylor, D.; Wang, Z. The role of environmental taxes on carbon emissions in countries aiming for net-zero carbon emissions: Does renewable energy consumption matter? Renew. Energy 2023, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Effective Carbon Rates 2021; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 9789264358911.

- IPCC. (2023). “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” accessed 03.04. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf.

- Mahmood, N.; Zhao, Y.; Lou, Q.; Geng, J. Role of environmental regulations and eco-innovation in energy structure transition for green growth: Evidence from OECD. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Ali, B.M.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. Environmental Policy and Innovation: A Decade of Research. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 13, 265–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Glachant, M.; Haščič, I.; Johnstone, N.; Ménière, Y. Invention and Transfer of Climate Change–Mitigation Technologies: A Global Analysis. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2011, 5, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Akcigit, U.; Bergeaud, A.; Blundell, R.; Hemous, D. Innovation and Top Income Inequality. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2018, 86, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Obobisa, E.S.; Ayamba, E.C. Achieving carbon neutrality goal in European countries: the role of green technology innovation, renewable energy, and financial development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D. Can green technology innovations achieve the collaborative management of pollution reduction and carbon emissions reduction? Evidence from the Chinese industrial sector. Environ. Res. 2024, 264, 120400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S. An econometric study of eco-innovation, clean energy, and trade openness toward carbon neutrality and sustainable development in OECD countries. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 3075–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, D.; Willeke, T. Which green path to follow: The development of green transportation technology under the EU ETS and its interplay with carbon emission reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145228–145228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Hayyat, M.; Henry, J. Green energy investment and technology innovation for carbon reduction: Strategies for achieving SDGs in the G7 countries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 114, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, L.S.; Paraschiv, S. Contribution of renewable energy (hydro, wind, solar and biomass) to decarbonization and transformation of the electricity generation sector for sustainable development. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Goi, N. RETRACTED: Balancing economic growth and ecological sustainability: Factors affecting the development of renewable energy in developing countries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 116, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S.; Chen, H.; Mensah, I.A. Transitions to sustainable development: the role of green innovation and institutional quality. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 6751–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Su, C.-W.; Umar, M.; Shao, X.; Lobonţ, O.-R. The race to zero emissions: Can renewable energy be the path to carbon neutrality? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde-Rufael, Y.; Mulat-Weldemeskel, E. The moderating role of environmental tax and renewable energy in CO2 emissions in Latin America and Caribbean countries: Evidence from method of moments quantile regression. Environ. Challenges 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, H.D. Historical evidence for energy efficiency rebound in 30 US sectors and a toolkit for rebound analysts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R. Do alternative energy sources displace fossil fuels? Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Li, X.F.; Wu, Q. Carbon taxes and emission trading systems: Which one is more effective in reducing carbon emissions?—A meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Raghutla, C.; Song, M.; Zameer, H.; Jiao, Z. Public-private partnerships investment in energy as new determinant of CO2 emissions: The role of technological innovations in China. Energy Econ. 2020, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Chu, L.K.; Ghosh, S.; Truong, H.H.D.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. How environmental taxes and carbon emissions are related in the G7 economies? Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.J. Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study. Am. Econ. Journal: Econ. Policy 2019, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, Lawrence and Hafstead, Marc. (2017). “III: POLICY APPROACHES AND OUTCOMES”. Confronting the Climate Challenge: U.S. Policy Options, New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, pp. 77-224. [CrossRef]

- Alola, A.A.; Muoneke, O.B.; Okere, K.I.; Obekpa, H.O. Analysing the co-benefit of environmental tax amidst clean energy development in Europe's largest agrarian economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 326, 116748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Acheampong, A.O. Reducing carbon emissions: The role of renewable energy and democracy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Hu, D.; Wang, Y. How do firms achieve sustainability through green innovation under external pressures of environmental regulation and market turbulence? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2695–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Payne, J.E. Renewable energy consumption and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, G.E. Designing a Carbon Tax to Reduce U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2008, 3, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve after 25 years. J. Bioeconomics 2017, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Yamagata, T. Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J. Econ. 2008, 142, 50–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for Error Correction in Panel Data*. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 69, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S., & Eberhardt, M. (2013). Accounting for unobserved heterogeneity in panel time series models. University of Oxford, 1(11), 1-12.

- Pesaran, M.H. Estimation and Inference in Large Heterogeneous Panels with a Multifactor Error Structure. Econometrica 2006, 74, 967–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.-I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels; Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, S.; Chen, S.; Danish; Haseeb, A. Impact of financial development and economic growth on environmental quality: an empirical analysis from Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2253–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, L.; Long, X.; Mensah, C.N.; Salman, M.; Boamah, K.B.; Ampon-Wireko, S.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Innovation, trade openness and CO2 emissions in selected countries in Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistline, J.E.; Blanford, G.J. The role of the power sector in net-zero energy systems. Energy Clim. Chang. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, A.; Jena, P.K.; Bekun, F.V.; Sahu, P.K. Symmetric and asymmetric impact of economic growth, capital formation, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on environment in OECD countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S. An econometric study of eco-innovation, clean energy, and trade openness toward carbon neutrality and sustainable development in OECD countries. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 3075–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, F. The environmental impacts of financial development in OECD countries: a panel GMM approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6758–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmi, R.; Alam, K. Dynamic relationship among environmental regulation, innovation, CO2 emissions, population, and economic growth in OECD countries: A panel investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Ni, W.; Zhang, C. The impact of carbon emissions trading on the directed technical change in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obobisa, E.S. Achieving 1.5 °C and net-zero emissions target: The role of renewable energy and financial development. Renew. Energy 2022, 188, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.; Xinbang, C.; Anwar, A. Do green technology innovations, financial development, and renewable energy use help to curb carbon emissions? Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Unit | Database |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide emission | Kiloton (kt) | WDI |

|

GTI |

Green technology innovation |

Number of patents for Environmental-related technologies |

OECD statistics |

| REC | Renewable energy consumption | % of total final energy | WDI |

| ETAX | Environmental taxes | Environmental taxes | OECD statistics |

| GDP | Gross domestic product per capita | Constant US 2010 | WDI |

| FEC | Fossil fuel energy consumption | % of total final energy | WDI |

| Variables | CO2 | GTI | REC | ETAX | FEC | GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 11.531 | 4.168 | 2.375 | 0.766 | 4.248 | 10.111 |

| Median | 11.197 | 4.265 | 2.402 | 0.874 | 4.379 | 10.371 |

| Max. | 15.569 | 9.249 | 4.348 | 1.681 | 4.590 | 14.027 |

| Min. | 7.528 | -1.772 | -0.817 | -4.200 | 2.328 | 7.431 |

| Std. Dev. | 1.558 | 2.380 | 1.054 | 0.471 | 0.386 | 0.834 |

| Skewness | 0.020 | -0.021 | -0.480 | -2.639 | -2.510 | -0.521 |

| Kurtosis | 3.216 | 2.399 | 2.801 | 19.172 | 10.229 | 3.730 |

| Jarque-Bera | 2.111 | 15.868 | 42.030 | 12660.510 | 3388.843 | 70.795 |

| Probability | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| N | 1050 | 1050 | 1050 | 1050 | 1050 | 1050 |

| VIF | / | 2.29 | 1.68 | 1.08 | 1.55 | 2.17 |

| Variable | CSD-test | Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 13.91*** | 0.51 | ||

| GTI | 105.88*** | 0.79 | ||

| REC | 42.72*** | 0.70 | ||

| ETAX | 17.53*** | 0.62 | ||

| GDP | 95.41*** | 0.79 | ||

| FEC | 36.17*** |

0.62 |

||

| Slope heterogeneity test | ||||

|

|

Adjusted | |||

|

35.220 (0.000) *** |

40.225 (000) *** |

|||

| Variable | CIPS | Remarks | |||||

| Level | 1st difference | ||||||

| CO2 | -1.524 | -4.712*** | Stationary | ||||

| GTI | -2.606 | -5.042*** | Stationary | ||||

| REC | -2.209 | -5.023*** | Stationary | ||||

| ETAX | -1.291 | -4.944*** | Stationary | ||||

| GDP | -1.888 | -3.210*** | Stationary | ||||

| FEC | -2.406 | -5.272*** | Stationary | ||||

| Statistics | Value | Z-value | Robust p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gt | -2.581*** | -3.508 | 0.000 |

| Ga | -11.625** | -2.358 | 0.009 |

| Pt | -14.616*** | -4.339 | 0.000 |

| Pa | -10.433*** | -4.833 | 0.000 |

| Variable | AMG | CCEMG |

|---|---|---|

| GTI | -0.019** (0.018) |

-0.023* (0.051) |

| REC | -0.210*** (0.000) |

-0.195*** (0.000) |

| ETAX | 0.033 (0.401) |

0.016 (0.586) |

| GDP | 0.404*** (0.000) |

0.337*** (0.000) |

| FEC | 0.835*** (0.001) |

0.632** (0.037) |

| Wald-Test | 62.34*** (0.000) |

49.55*** (0.000) |

| Null Hypothesis | Stats | tats |

|

Direction of causality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTI CO2 | 3.279*** | 7.953 | 0.000 | ||||

| CO2 GTI | 3.574*** | 9.023 | 0.000 | ||||

| REC CO2 | 4.274*** | 11.556 | 0.000 | ||||

| CO2 REC | 4.592*** | 12.712 | 0.000 | ||||

| ETAX CO2 | 1.945*** | 3.122 | 0.002 | ||||

| CO2 ETAX | 3.602*** | 9.125 | 0.000 | ||||

| GDP CO2 | 3.610*** | 9.154 | 0.000 | ||||

| CO2 GDP | 3.053*** | 7.134 | 0.000 | ||||

| FEC CO2 | 2.769*** | 6.106 | 0.000 | ||||

| CO2 FEC | 2.625*** | 5.584 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).