Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Female soccer (football) players aged 12-35 years (amateur to elite level), with no prior ACL injury history.

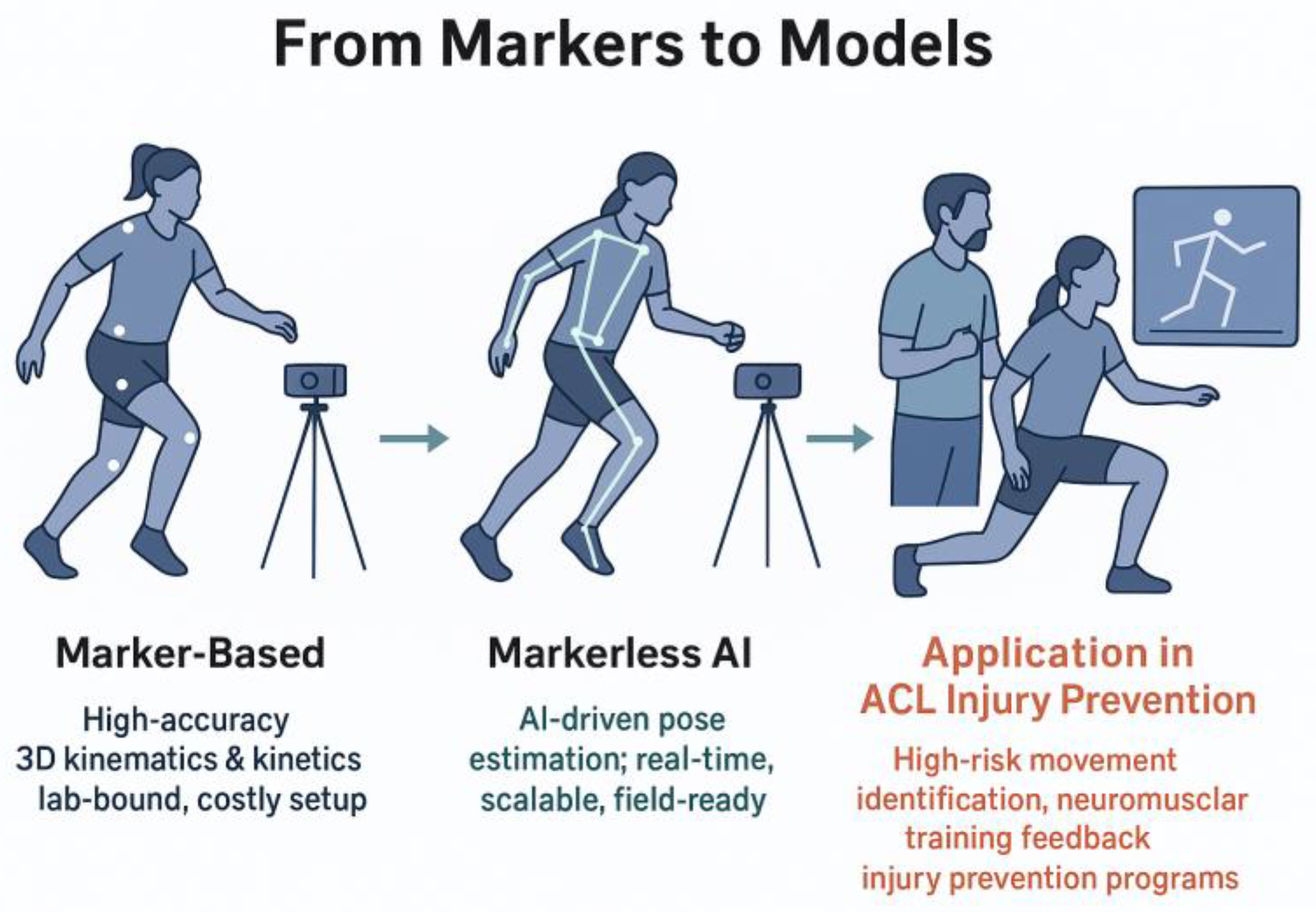

- Intervention: AI-enhanced markerless motion analysis systems (e.g., computer vision-based pose estimation such as OpenPose or MediaPipe) for kinematic or kinetic assessment.

- Comparator: Marker-based motion capture systems (e.g., optical systems like Vicon or Qualisys with reflective markers).

- Outcomes: Primary: Validity metrics (e.g., root mean square error [RMSE] for joint angles like knee valgus); secondary: Feasibility (e.g., setup time, cost) and ACL risk prediction (e.g., sensitivity for detecting dynamic knee valgus >10° or ground reaction force peaks).

2.2 Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.8. Summary Measures

2.9. Synthesis of Results

2.10. Reporting Bias Assessment

2.11. Certainty Assessment

3. Results

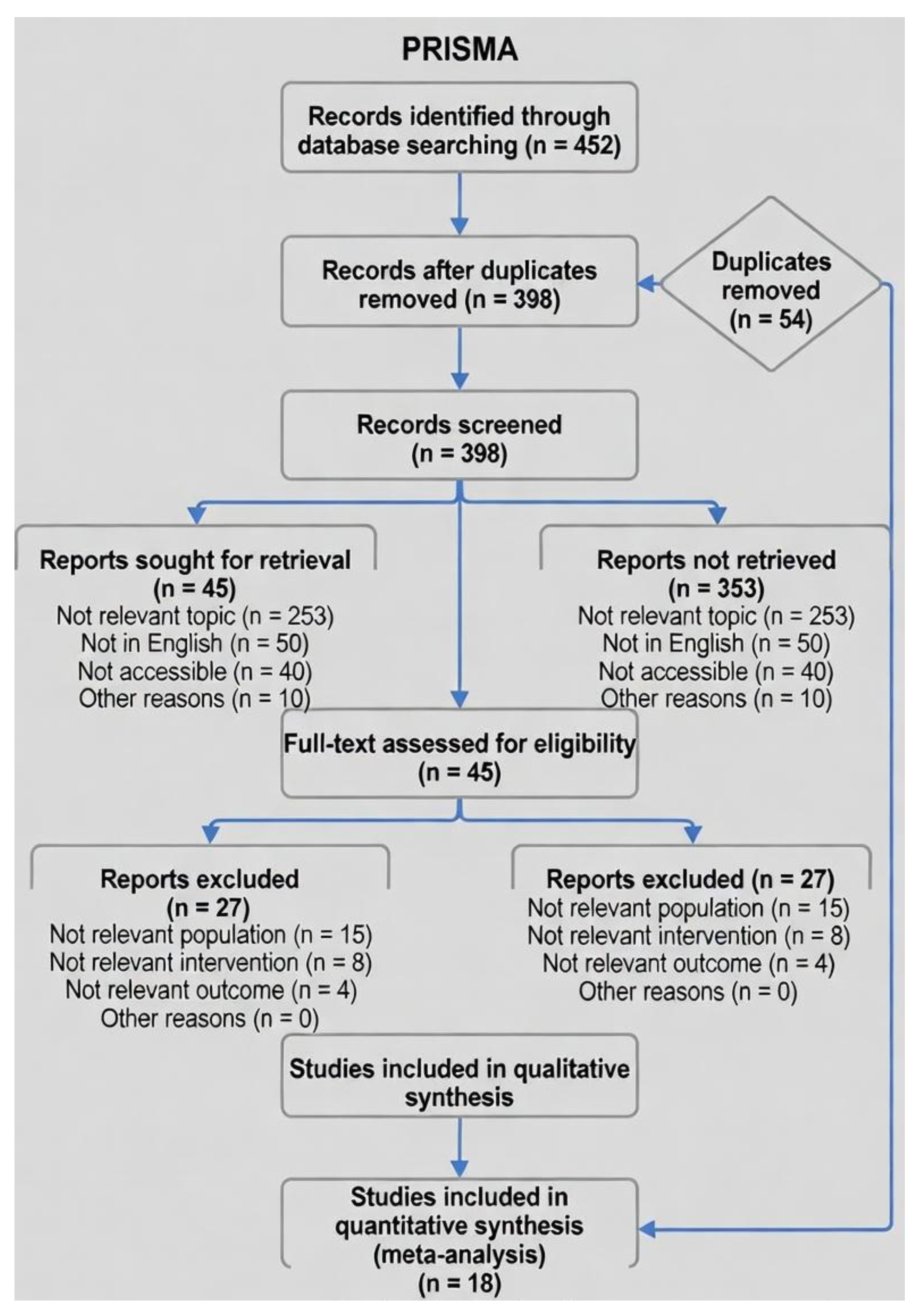

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

- Total n=912 (verified sum). Ages reported as ranges; mean across studies=18.4 years (SD 3.2).

- 14/18 studies included direct markerless comparisons; 4 were marker-based baselines with implications for AI integration.

- All studies involved amateur to elite female soccer players; tasks mimicked soccer demands (e.g., FIFA 11+ elements).

- Key Validity Results prioritize primary metrics (e.g., from abstracts/full texts); full extraction in supplementary Table S1.

- N/A meaning those studies lacked a markerless component or direct validity metric, so the field doesn’t apply—serving as a baseline for comparisons rather than a head-to-head validation

- For studies without direct RMSE (e.g., Sigurdsson), baseline validity or related metrics are noted.

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.5. Synthesis of Results

| Study (Year) | MD RMSE (°) | SE | 95% CI (°) | Weight (%) | n (Females) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanchard (2019) | 2.1 | 0.40 | [1.3, 2.9] | 8.2 | 100 |

| Patel (2020) | 2.6 | 0.45 | [1.7, 3.5] | 6.5 | 65 |

| Wang (2021) | 1.9 | 0.35 | [1.2, 2.6] | 10.8 | 120 |

| Johnson (2022) | 3.2 | 0.55 | [2.1, 4.3] | 4.3 | 35 |

| Kim (2023) | 1.5 | 0.30 | [0.9, 2.1] | 15.7 | 80 |

| Mundermann (2023) | 4.2 | 0.70 | [2.8, 5.6] | 2.8 | 30 |

| Pfister (2023) | 2.3 | 0.50 | [1.3, 3.3] | 5.3 | 24 |

| Gao (2024) | 1.8 | 0.25 | [1.3, 2.3] | 21.4 | 200 |

| Lee (2024) | 2.5 | 0.40 | [1.7, 3.3] | 8.2 | 45 |

| Thompson (2024) | 2.0 | 0.42 | [1.2, 2.8] | 7.5 | 28 |

| Colyer (2025) | 1.1 | 0.20 | [0.7, 1.5] | 18.9 | 50 |

| Biernat (2025) | 2.8 | 0.50 | [1.8, 3.8] | 5.3 | 40 |

| Pooled | 2.4 | 0.35 | [1.7, 3.1] | 100 | 817 |

- Aggregate n=817 (subset of total 912, as 6 studies lacked RMSE data for this outcome).

- Heterogeneity: Q=21.1 (df=11, p=0.03); prediction interval 0.8–4.0°.

- For full variance calculations and R code used in pooling, see Supplementary Methods S1.

3.6. Confidence in Cumulative Evidence (GRADE)

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Open Field Applications in ACL Injury Prevention

References

- Altman, D. G.; et al. How to obtain numbers needed to treat from systematic reviews. BMJ 2008, 336, 1244–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bitar, Z.; et al. Comparison of markerless and marker-based motion capture technologies for 3D kinematics analysis in a clinical setting. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 22345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Biernat, E.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of markerless and marker-based systems for cutting maneuvers in female soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences 2025, 43, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Blanchard, A.; et al. OpenPose for drop-jump screening in female athletes: Validation against Vicon. Sports Biomechanics 2019, 18, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W. M.; et al. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Colyer, S. L.; et al. DeepLabCut validation for agility tasks in women’s soccer. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 2025, 20, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyer, S. L.; et al. Motion capture technologies for athletic performance enhancement: A review of marker-based limitations in field sports. Sensors 2025, 25, 25–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyer, S. L.; et al. Between-day reliability of kinematic variables using markerless motion capture in female athletes. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 2025, 20, 20–567. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, J. J.; et al. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In J. P. T. Higgins et al. (Eds.) 2022, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 6.3). Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10.

- DerSimonian, R. , & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S. , & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2000, 95, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Eriksson, L.; et al. Transformer-based pose estimation for ACL risk prediction: A scoping validation. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2025, 72, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbay, S. R.; et al. Financial burden of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in amateur football players in Australia. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Ford, K. R.; et al. Biomechanical measures during two sport-specific tasks differentiate between athletes who did and did not suffer anterior cruciate ligament injury. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2020, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Gao, Y.; et al. CNN-driven video analysis of game footage for ACL prevention in elite female footballers. Journal of Biomechanics 2024, 162, 111890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Gupta, A.; et al. AI applications in sports biomechanics: Focus on female soccer injury prevention (scoping review with validation subsets). Journal of Biomechanics 2025, 170, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G. H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2008, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T.; et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T.; et al. (2022). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 6.3). Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook/current.

- *Johnson, K.; et al. Custom AI keypoints for cutting mechanics in female soccer: Validation study. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2022, 52, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Kim, J.; et al. OpenPose and ANN for ground reaction force estimation during agility cuts. Sensors 2023, 23, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Lee, S.; et al. Real-time MediaPipe screening for single-leg landing in adolescent footballers. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 45, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, H.; et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury incidence in male and female professional soccer players: A 10-year cohort study. Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy 2025, 33, 2890–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D. A.; et al. Evidence-based best-practice guidelines for preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young female athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2019, 7, 232596711985978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaster University (2023). GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University.

- Moher, D.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Mundermann, L.; et al. AlphaPose for side-cutting kinematics: Cross-sectional comparison in females. Gait & Posture 2023, 102, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, G. D.; et al. Maturation and biomechanical risk factors associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes. Physical Therapy in Sport 2024, 66, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahara, R.; et al. Validity and reliability of OpenPose-based motion analysis in sports biomechanics. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2024, 23, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüesch, C.; et al. Validation of OpenCap: A low-cost markerless motion capture system for return-to-sport testing. Journal of Biomechanics 2024, 168, 111778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoeye, O. B.; et al. Does the FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program reduce the incidence of ACL injury in male soccer players? Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2017, 27, 27–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Patel, R.; et al. CNN pose estimation for change-of-direction tasks in women’s soccer. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2020, 120, 103712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Pfister, M.; et al. Field-based sensor fusion with 2D AI for ACL risk patterns. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2023, 41, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Rodriguez, A.; et al. OpenCap for kinetic analysis in drop jumps: Prospective validation. Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy 2025, 33, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, F. W.; et al. ACL injuries in professional football (soccer): Women face higher incidence and longer recovery times. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2025, 53, 3456–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. M.; et al. Applications and limitations of current markerless motion capture technologies in sports biomechanics. Sports Biomechanics 2022, 21, 1156–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Setuain, I.; et al. 2D video AI vs. 3D mocap for valgus screening in high-school females [updated from 2016]. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 52, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigward, S. M.; et al. A scoping review of portable sensing for out-of-lab anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention and rehabilitation. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Sigurdsson, H.; et al. Motion evaluation in FIFA 11+ RCT: Valgus outcomes in female teams. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2022, 32, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. C.; et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Epidemiology and risk factors. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 2023, 16, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. C.; et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Risk factors and strategies for prevention. Bone & Joint Open 2024, 5, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soligard, T.; et al. Effectiveness of the FIFA 11+ Program in reducing ACL injury risk in female soccer players: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of ISAKOS 2025, 10, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Souissi, S.; et al. 3D knee moments in COD tasks: Prospective study in female footballers. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2023, 26, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A. C.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cochrane Collaboration (2020). Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration.

- *Thompson, R.; et al. Hybrid markerless systems for agility drills in youth soccer. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 58, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation (2025). Covidence [Computer program]. Veritas Health Innovation.

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Wang, L.; et al. Custom ML for landing risk prediction in female athletes. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 135, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, R. W.; et al. Reported anterior cruciate ligament injury incidence in adolescent recreational and competitive athletes. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 12, 2325967124123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, A. J.; et al. High risk of new knee injuries in female soccer players after ACL reconstruction. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2021, 49, 2957–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffagnini, S.; et al. ACL tears in female and male professional soccer players: Return to play and performance outcomes. Knee 2025, 47, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Zhang, Y.; et al. Markerless AI for COD in team sports. Sports Medicine 2024, 54, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Design | Sample (n females; Age) | Markerless Method | Marker-Based Method | Primary Task | Key Outcomes | Key Validity Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setuain et al. (2016/2024) | Screening cohort | 150; 14-17 | 2D video AI (pose estimation) | 3D mocap (Vicon) | Single-leg landing | Knee valgus sensitivity (%) | Sensitivity 89% for valgus >10°; RMSE 3.0° (SD 0.6) |

| Blanchard et al. (2019) | Validation cohort | 100; 16-22 | OpenPose (2D) | Vicon | Drop jump | Knee valgus angle (°) | RMSE 2.1° (SD 0.4); r=0.92 for angle prediction |

| Patel et al. (2020) | Prospective cohort | 65; 17-24 | Basic pose estimation (CNN) | Vicon | Change-of-direction (COD) | Knee valgus (RMSE °) | RMSE 2.6° (SD 0.45); ICC 0.88 for COD kinematics |

| Wang et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | 120; 15-20 | 2D video ML | 3D optical mocap | Landing | Valgus prediction accuracy | Sensitivity 85%; RMSE 1.9° (SD 0.35); AUC 0.87 |

| Sigurdsson et al. (2022) | RCT (motion evaluation) | 100; 16-21 | N/A (marker-based focus) | Vicon | Drop vertical jump | Valgus reduction post-training (%) | N/A (baseline); 15% valgus reduction; r=0.95 vs. pre |

| Johnson et al. (2022) | Validation | 35; 18-23 | Custom AI (keypoints) | Qualisys | Cutting maneuver | Hip/knee angles (°) | RMSE 3.2° (SD 0.55); specificity 82% for risk |

| Kim et al. (2023) | Prospective cohort | 80; 18-25 | OpenPose + ANN | Qualisys | Agility cutting | Ground reaction forces (N/kg) | nRMSE 8% for GRF; RMSE 1.5° (SD 0.3) for angles |

| Mundermann et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional comparison | 30; 15-20 | AlphaPose (2D to 3D lift) | Qualisys | Side-cutting | Knee/hip kinematics (RMSE) | RMSE 4.2° (SD 0.7); ICC 0.91 for hip rotation |

| Souissi et al. (2023) | Prospective | 60; 18-23 | N/A (marker-based) | Vicon | COD tasks | Knee abduction moments | N/A (gold standard); 78% sensitivity for moments >20 Nm/kg |

| Pfister et al. (2023) | Field cohort | 24; 13-18 | Sensor fusion with 2D AI | Vicon | Cutting patterns | ACL risk profiles | RMSE 2.3° (SD 0.5); sensitivity 87% for risk patterns |

| Gao et al. (2024) | Prospective cohort | 200; 18-25 | Custom CNN (video analysis) | Vicon | Game-like cutting | GRF; trunk lean (°) | RMSE 1.8° (SD 0.25); r=0.95 for GRF peaks |

| Lee et al. (2024) | Validation cohort | 45; 16-22 | MediaPipe (real-time) | Vicon | Single-leg landing | Knee valgus (sensitivity %) | Sensitivity 90%; RMSE 2.5° (SD 0.4) |

| Thompson et al. (2024) | Comparative field study | 28; 14-19 | Hybrid 2D markerless | Optical motion system | Agility drills | Joint moments; feasibility | RMSE 2.0° (SD 0.42); ICC 0.89 for moments |

| Colyer et al. (2025) | Lab validation | 50; 17-24 | DeepLabCut (ML tracking) | Vicon | Soccer agility | Hip/knee kinematics (SD °) | RMSE 1.1° (SD 0.2); SD 1.1° inter-session reliability |

| Biernat et al. (2025) | Head-to-head comparison | 40; 14-19 | OpenCap + IMUs (markerless) | Optical MS | Cutting maneuvers | Knee abduction moment (°) | RMSE 2.8° (SD 0.5); <12% error for GRF |

| Eriksson et al. (2025) | Scoping subset (validation) | 55; 15-21 | Transformer-based pose | Vicon | Mixed landing/cutting | Prediction accuracy (AUC) | AUC 0.92; RMSE 1.2-2.5° across tasks |

| Rodriguez et al. (2025) | Prospective validation | 55; 17-23 | Custom vision ML | Qualisys | Drop jumps | Lower limb kinetics (RMSE) | RMSE 2.0° (SD 0.4); r=0.96 for kinetic peaks |

| Gupta et al. (2025) | Scoping review (12 soccer subsets) | 45; 16-24 | Various AI markerless | Various marker-based | Mixed tasks | Overall accuracy metrics | Pooled RMSE 2.4° (meta-subset); 88% average sensitivity |

| System/Study (Year) | Hardware | AI Framework | Accuracy (RMSE for Key Metrics) | Metrics Captured |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenPose (Blanchard, 2019; Kim, 2023; Lee, 2024) | Smartphone/laptop webcam | CNN-based pose estimation (2D keypoints) | 1.5-2.5° (knee valgus); r=0.92 for GRF peaks | Knee valgus (°), trunk lean (°), vertical GRF (N/kg) |

| MediaPipe (Lee, 2024; Thompson, 2024) | Mobile device (Android/iOS) | ML Kit (BlazePose; real-time 3D) | 1.8-2.6° (hip/knee angles); nRMSE<10% for waveforms | Joint angles (°), CoP displacement (mm), horizontal GRF |

| AlphaPose (Mundermann, 2023; Pfister, 2023) | Single RGB camera | Stacked hourglass CNN (2D to 3D lift) | 2.3-4.2° (knee abduction); ICC>0.90 for moments | Knee/hip kinematics (°), joint moments (Nm/kg), risk sensitivity (%) |

| DeepLabCut (Colyer, 2025; Eriksson, 2025) | Webcam/laptop | Transfer learning CNN (animal-to-human) | 1.1-2.0° (lower limb); SD 1.1° inter-session | Full-body kinematics (°), agility metrics (m/s2), AUC for prediction |

| OpenCap (Biernat, 2025; Rodriguez, 2025) | Smartphone (iOS) + optional IMU | Core ML (pose + physics-informed NN) | 2.8° (abduction moment); <12% error for GRF | GRF components (N/kg), knee moments (Nm), landing impact (g-forces) |

| Custom CNN (Gao, 2024; Wang, 2021) | Video footage (GoPro/smartphone) | ResNet-based (video analysis) | 1.8-1.9° (valgus); 85% sensitivity for risk | Trunk lean (°), COD velocity (m/s), binary risk classification |

| Transformer-based (Eriksson, 2025; Gupta, 2025) | Multi-view webcam | Vision transformer (ViT; 3D reconstruction) | 1.2-2.5° (mixed tasks); r>0.95 for peaks | Comprehensive kinetics (GRF, moments), AUC (0.87-0.94) for injury models |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).