Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introuduction

2. Materials and Methods

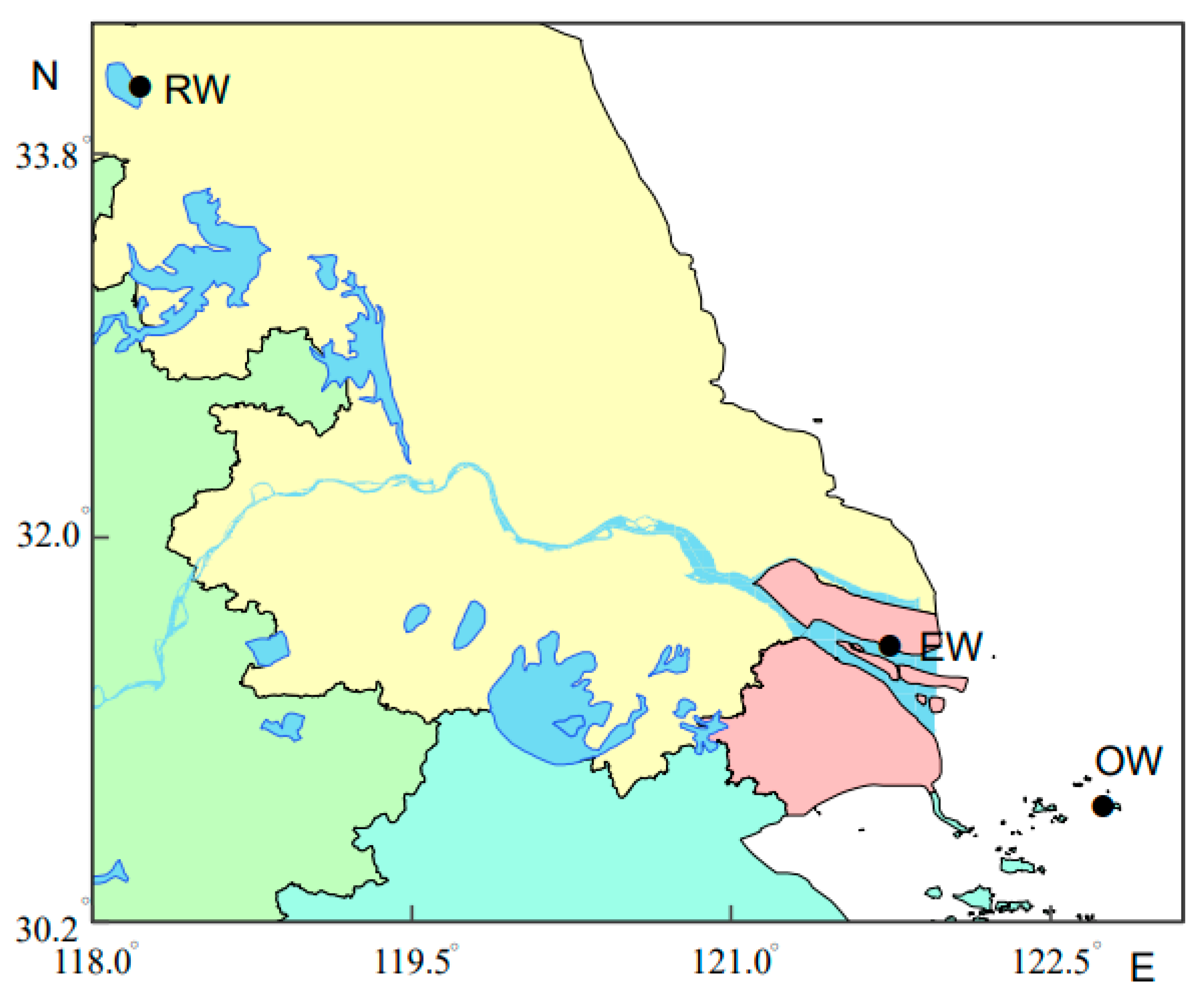

2.1. Sampling Sites, Sample Collection, and Processing

2.2. Elemental Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

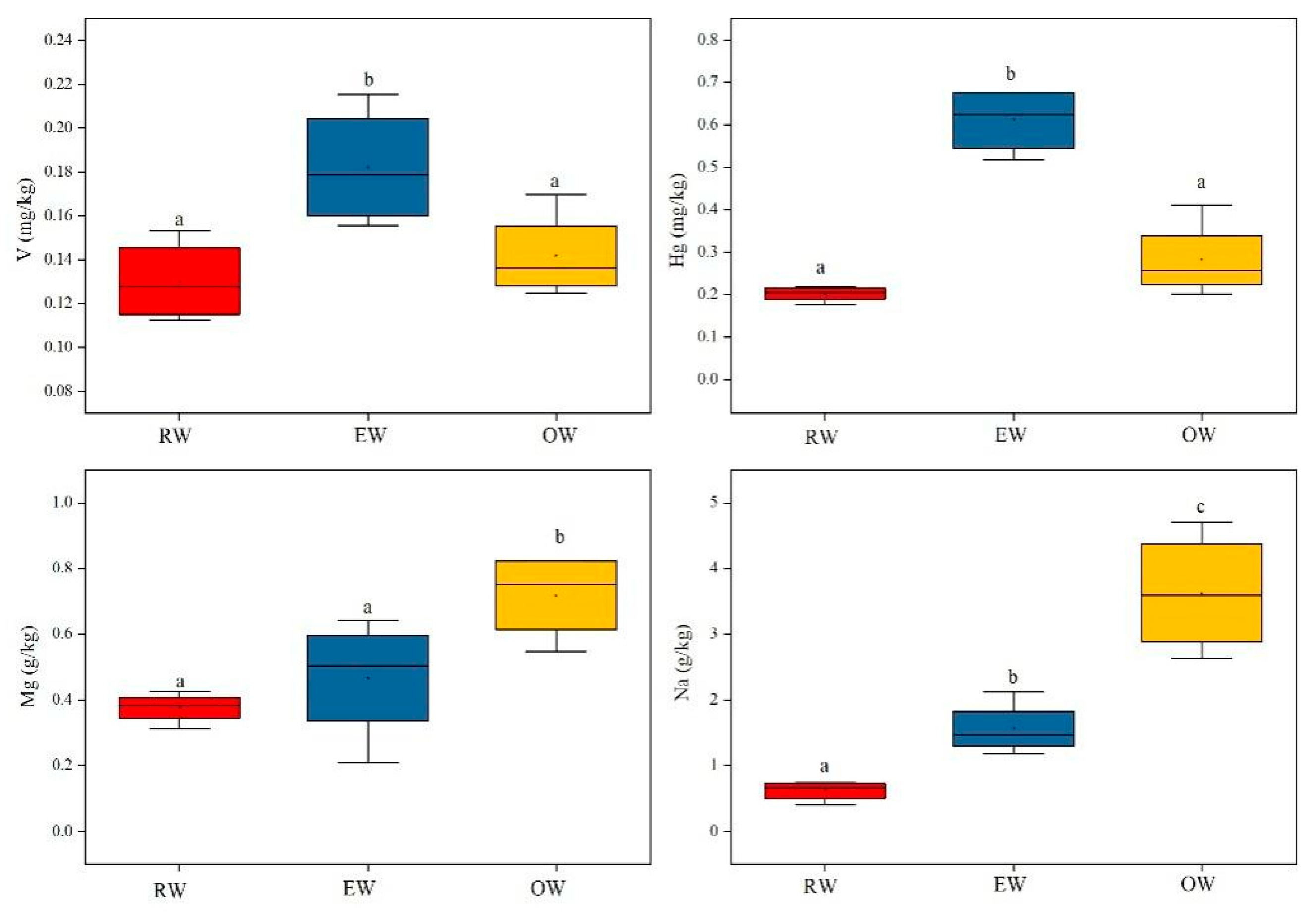

3.1. Elemental Fingerprints Composition

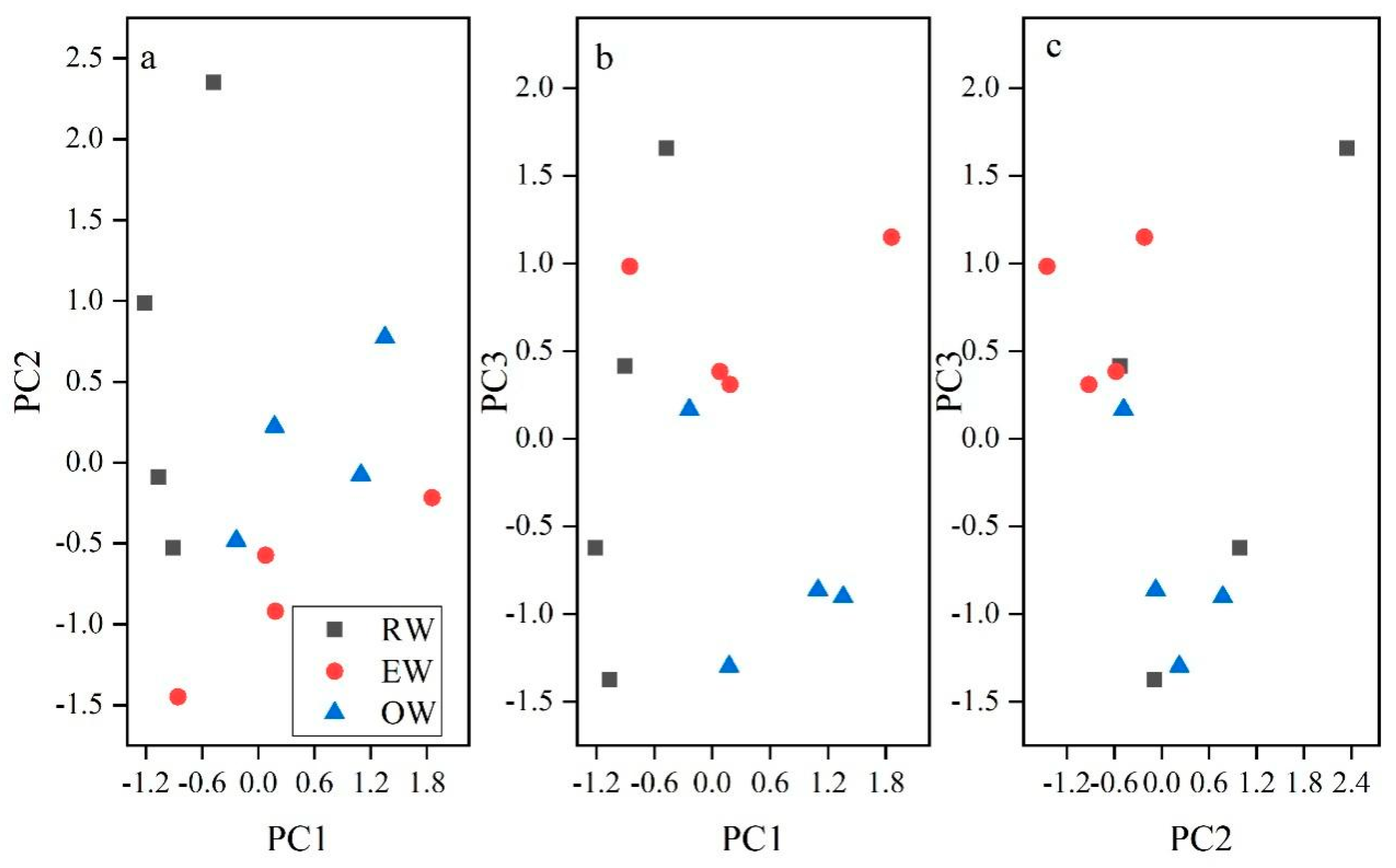

3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

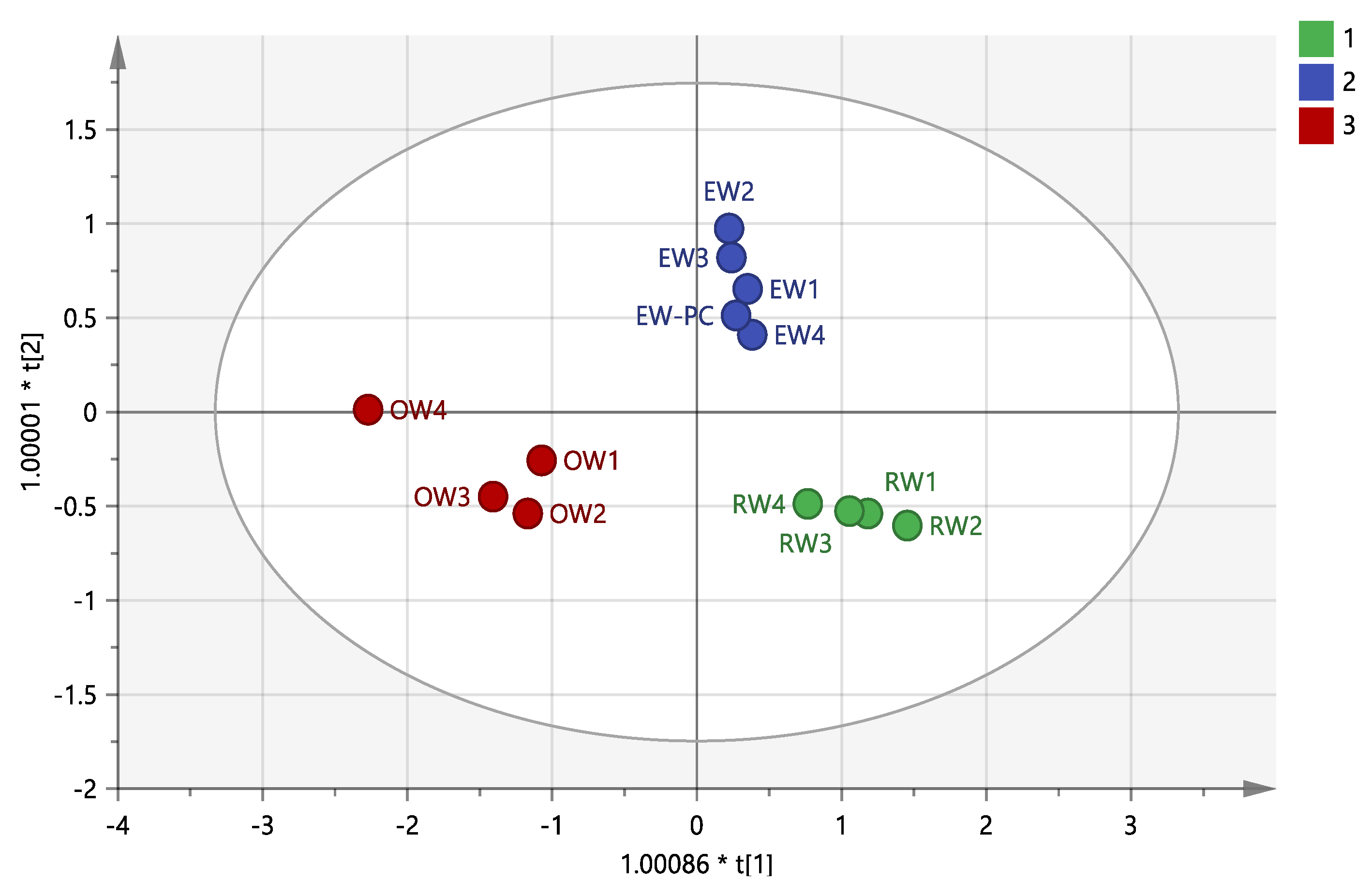

3.3. Discriminant Element Screening

3.4. Traceability and Verification Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhuang, P. Native and Exotic Fishes of the Middle and Lower Yangtze River; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Hu, W.; Feng, G.; Zhuang, P.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, S.; Yang, G. Study on the Conservation and Sustainable Utilization Management of Auguilla Japonica Fry Resources in the Yangtze River Estuary. Modern Fisheries Information 2024, 39, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.S.; Hwang, J.-A.; Kim, S.-K.; Cha, Y.; Oh, S.-Y. Influence of Biofloc Technology and Continuous Flow Systems on Aquatic Microbiota and Water Quality in Japanese Eel Aquaculture. Diversity 2024, 16, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zang, X.; Kondyukov, G.; Hou, Z.; Peng, G.; Pander, J.; Knott, J.; Geist, J.; Melesse, M.B.; Jacobson, P.; et al. Towards Automated and Real-Time Multi-Object Detection of Anguilliform Fishes from Sonar Data Using YOLOv8 Deep Learning Algorithm. Ecological Informatics 2025, 91, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Hua, C.; Zhu, Q. Analysis of morphological differences and discrimination between female and male Cololabis saira based on geometric morphometrics. South China Fisheries Science 2024, 20, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, G. Identification of Geographical Populations of Nototheniops Larseni Based on Geometric Shape of Otoliths. Marine Fisheries 2025, 47, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Shao, B.; Miao, T.; Peng, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, S. Identification of Six Eel Species Using Polygenic DNA Barcoding. Food Science 2018, 39, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Li, X. Salmon Origin Traceability Based on Fatty Acid Fingerprints. Food Research and Development 2025, 46, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Wang, H.; Feng, J.; Feng, Z.; Li, W.; Tang, Z. Origin Traceability of “Jinwan Huangliyu” Based on Stable Isotope Ratio Signature. Modern Agricultural Science and Technology 136-140+144. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Han, G.; Liang, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhong, Q. Multivariate Discrimination of Chinese Vinegars Using Multi-Element: Implications for Origin Traceability and Dietary Safety. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2025, 145, 107807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilaka, C.A.; Aparicio-Muriana, M. del M.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Quinn, B.; Birse, N.; Elliott, C.T. A Combined Elementomics, Metabolomics, and Chemometrics Approach as Tools to Identify the Geographic Origins of Black Pepper. Food Chemistry 2025, 492, 145420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X. Multielemental Analysis Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry and Optical Emission Spectroscopy for Tracing the Geographical Origin of Food. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2025, 80, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Ricardo, F.; Mamede, R.; Díaz, S.; Patinha, C.; Calado, R. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Elemental Fingerprints of Ruditapes Philippinarum Shells and Its Influence on the Confirmation of Harvesting Location and Time. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2025, 324, 109444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, R.; Duarte, I.A.; Tanner, S.E.; Fonseca, V.F.; Duarte, B. Multi-Elemental Fingerprints of Edible Tissues of Common Cockles (Cerastoderma Edule) to Promote Geographic Origin Authentication, Valorization, and Food Safety. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2025, 140, 107291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, X.; Ha, L.; Ao, Q.; Dong, X.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Y. Application of Stable Isotopes and Mineral Elements Fingerprinting for Beef Traceability and Authenticity in Inner Mongolia of China. Food Chemistry 2025, 465, 141911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xuan, Z.; Ma, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, K. Otolith microchemistry provides evidence for the existence of migratory Coilia nasus in Chaohu Lake and traces their natal origins. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China 2025, 32, 742–752. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Zhao, L.; Fan, Y.; Qu, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y. Using Whole Body Elemental Fingerprint Analysis to Distinguish Different Populations of Coilia Nasus in a Large River Basin. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2015, 60, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunito, T.; Watanabe, I.; Yasunaga, G.; Fujise, Y.; Tanabe, S. Using Trace Elements in Skin to Discriminate the Populations of Minke Whales in Southern Hemisphere. Marine Environmental Research 2002, 53, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Deghel, N.; Vieira, H.C.; Bordalo, M.D.; Peuble, S.; Gallice, F.; Bedell, J.-P. Metallic Trace Elements in Wild and Farmed Fish from the Aveiro Region (Portugal). Marine Pollution Bulletin 2025, 222, 118774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, J.; García-Cegarra, A.M.; Martínez-López, E. Heavy Metals and Trace Elements in a Threatened Population of Guanay Cormorants (Leucocarbo Bougainvilliorum) from an Industrialized Bay in the Humboldt Current System, Chile. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2025, 92, 127749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussinet, E.; Daverat, F.; Bareille, G.; Scharbert, A.; Stoll, S. Determining the Natal Origin of the Reintroduced Allis Shad (Alosa Alosa) in the Rhine River Using Otolith Microchemistry. Environmental Biology of Fishes 2025, 108, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, M.; Shan, X.; Jiang, R.; Yin, R. Habitat use history of Coilia nusus in Oujiang River Estuary based on otolith microchemistry. Journal of Fisheries of China 2025, 49, 079308–079308. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Du, N.; Wu, S.; Tang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, P.; Gao, L.; Qin, D. Multi-Element Fingerprints of Muscle Tissues of Eriocheir Sinensis from 8 Major Production Areas in China to Promote Geographical Origin and Food Safety Authentication. Food Chemistry: X 2025, 31, 103088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Sultana, S.; Kabiraj, M.; Das, M. Role of Micro and Macronutrients Enrich Fertilizers on the Growth Performance of Prawn (Macrobrachium Rosenbergii), Rohu (Labeo Rohita) and Mola (Amblypharyngodon Mola) in a Polyculture System. International Journal of Agricultural Research, Innovation and Technology 2018, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Dou, C.; Yan, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, D. Exploring the Feasibility of Multi-Element Fingerprinting with Chemometrics for Discriminating the Geographical Origins of Asparagus and Its Risk Assessment. Food Chemistry 2025, 495, 146395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, A.E.; Ricardo, F.; Patinha, C.; Silva, E.F.D.; Correia, M.; Palma, J.; Planas, M.; Calado, R. Successful Use of Geochemical Tools to Trace the Geographic Origin of Long-Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus Guttulatus Raised in Captivity. Animals 2021, 11, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, R.C.; de Souza, T.L.; Latif, A.L.O.; Souza e Souza, L.B.; de Freitas Santos Júnior, A.; dos Santos Lobo, L.; Junior, J.B.P.; Araujo, R.G.O.; Souza, L.A.; Santos, D.C.M.B. Quantification of Essential and Potentially Toxic Elements in Paprika (Capsicum Annuum L.) Varieties by ICP OES and Application of PCA and HCA. Food Chemistry 2025, 482, 144152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, G.C.; dos Santos, A.S.; Araujo, R.G.O.; Korn, M.G.A.; Santana, R.M.M. Multivariate Optimization of the Infrared Radiation-Assisted Digestion of Bivalve Mollusk Samples from Brazil for Arsenic and Trace Metals Determination Using ICP OES. Food Chemistry 2025, 477, 143460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.; Kahfi, J.; Dutta, A.; Jaremko, M.; Emwas, A.-H. The Detection of Adulteration of Olive Oil with Various Vegetable Oils – A Case Study Using High-Resolution 700 MHz NMR Spectroscopy Coupled with Multivariate Data Analysis. Food Control 2024, 166, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, I.C. Vital Statistics: Experimental Design for the Life Sciences by G.D. Ruxton and N. Colegrave. Oxford University Press, 2003. £14.99 Pbk (132 Pages) ISBN 0 19 925232 7. Modern Statistics for the Life Sciences by A. Grafen and R. Hails. Oxford University Press, 2002. £22.99 Pbk (384 Pages) ISBN 0 19 925231 9. Experimental Design and Data Analysis for Biologists by G.P. Quinn and M.J. Keough. Cambridge University Press, 2002. £75.00 Hbk (556 Pages) ISBN 0 521 00976 6. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2003, 18, 559–560. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, H.; Wu, D.; Zeng, G.; Chen, W.; Tao, Y.; Ding, B. Non-Target Screening and Identification of the Significant Quality Markers in the Wild and Cultivated Cordyceps Sinensis Using OPLS-DA and Feature-Based Molecular Networking. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2023, 51, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosabal, M.; Pierron, F.; Couture, P.; Baudrimont, M.; Hare, L.; Campbell, P.G.C. Subcellular Partitioning of Non-Essential Trace Metals (Ag, As, Cd, Ni, Pb, and Tl) in Livers of American (Anguilla Rostrata) and European (Anguilla Anguilla) Yellow Eels. Aquatic Toxicology 2015, 160, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Mochioka, N. Morphological and Genetic Identification of Bathyuroconger Parvibranchialis (Anguilliformes: Congridae) Leptocephali from Kuroshio Extension. Ichthyological Research 2025, 72, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windom, H.L.; Savidge, W.B. Sources and Transport Pathways of Trace Metals to the Outer Continental Shelf off South Carolina and Georgia, USA Revealed from the Otoliths of Moray Eels. Continental Shelf Research 2024, 282, 105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, S.; Kaya, G. Biomonitoring of Toxic and Essential Trace Elements in Different Tissues of Fish Species in Turkiye. Food Additives & Contaminants Part B-Surveillance 2023, 16, 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzi, I.; Pergantis, S.A.; Black, K.D.; Shimmield, T.M.; Papageorgiou, N.; Tsapakis, M.; Karakassis, I. Metals in Tissues of Seabass and Seabream Reared in Sites with Oxic and Anoxic Substrata and Risk Assessment for Consumers. Food Chemistry 2016, 194, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Feng, H.; Zou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, P.; Ji, Y.; Lek, S.; Guo, Z.; Fu, Q. Feeding Habit-Specific Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation and Health Risk Assessment of Fish in a Tropical Reservoir in Southern China. Fishes 2023, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehel, J.; Plachy, M.; Palotás, P.; Bartha, A.; Budai, P. Possible Metal Burden of Potentially Toxic Elements in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) on Aquaculture Farm. Fishes 2024, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, L.; Ji, W.; Ruan, W.; Xu, Y. Different Fractions and Potential Ecological Riskassessment of V, Cr, Co, Ni in Sediments of the Yangtze River Estuary. Marine Fisheries 2023, 45, 490–499. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Yang, S.; Yin, D.; Wang, R. Geochemical Controls on the Distribution of Total Mercury and Methylmercury in Sediments and Porewater from the Yangtze River Estuary to the East China Sea. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 892, 164737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, N.; Wu, M.; Wu, P.; He, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Fang, S. Sources and Ecological Risk Assessment of the Seawater Potentially Toxic Elements in Yangtze River Estuary during 2009–2018. Environ Monit Assess 2021, 193, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Sampling Waters | Collection Month | Number | Standard Length (cm) | Wet weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RW | River waters | July | 4 | 68.65±5.36a | 580.34±154.12a |

| EW | Estuary waters | July | 4 | 71.30±22.53a | 759.63±636.30a |

| OW | Offshore waters | July | 4 | 72.40±6.11a | 666.30±96.89a |

| Index | RW | EW | OW | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 2.150±1.035a | 4.653±2.067a | 4.165±1.623a | 0.077 |

| Ti | 1.895±0.965a | 1.517±0.425a | 1.613±0.092a | 0.874 |

| V | 0.131±0.018a | 0.183±0.027b | 0.142±0.020a | 0.044 |

| Cr | 5.579±0.413a | 5.985±0.342a | 5.097±0.848a | 0.174 |

| Mn | 0.833±0.556a | 1.406±0.696a | 0.845±0.110a | 0.298 |

| Fe | 74.093±135.460a | 18.160±8.556a | 14.298±3.852a | 0.551 |

| Co | 0.147±0.132a | 0.061±0.034a | 0.044±0.005a | 0.694 |

| Ni | 0.843±0.669a | 0.476±0.093a | 0.717±0.344a | 0.491 |

| Cu | 1.513±0.955a | 0.795±0.655a | 1.205±0.847a | 0.551 |

| Zn | 42.306±7.280a | 63.862±18.447a | 57.310±14.201a | 0.167 |

| As | 0.409±0.092a | 0.733±0.443a | 0.896±0.703a | 0.390 |

| Sr | 1.571±0.668a | 3.661±3.156a | 3.668±1.894a | 0.155 |

| Mo | 0.131±0.106a | 0.075±0.020a | 0.062±0.008a | 0.292 |

| Cd | 0.031±0.024a | 0.030±0.023a | 0.040±0.014a | 0.758 |

| Ba | 0.627±0.164a | 0.969±0.373a | 0.895±0.279a | 0.123 |

| Hg | 0.201±0.018a | 0.611±0.078b | 0.281±0.091a | 0.012 |

| Pb | 0.598±0.569a | 0.302±0.125a | 0.400±0.029a | 0.735 |

| Ca | 1.311±0.808a | 1.583±0.834a | 0.840±0.452a | 0.397 |

| K | 4.930±1.120a | 6.200±1.880a | 6.820±0.508a | 0.116 |

| Mg | 0.375±0.047a | 0.465±0.186a | 0.718±0.132b | 0.031 |

| Na | 0.617±0.156a | 1.561±0.401b | 3.628±0.920c | 0.007 |

| Variable | Principal Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Al | 0.852 | -0.292 | 0.238 | 0.122 | -0.196 |

| Ti | 0.112 | 0.859 | 0.298 | 0.191 | 0.162 |

| V | 0.036 | -0.634 | 0.236 | 0.216 | 0.479 |

| Cr | -0.31 | -0.481 | 0.641 | 0.13 | 0.166 |

| Mn | -0.053 | -0.426 | 0.398 | 0.644 | -0.365 |

| Fe | -0.346 | 0.275 | -0.194 | 0.798 | 0.157 |

| Co | -0.392 | 0.187 | -0.373 | 0.666 | 0.352 |

| Ni | 0.072 | 0.815 | 0.34 | -0.329 | 0.016 |

| Cu | 0.213 | 0.707 | -0.337 | 0.484 | 0.136 |

| Zn | 0.809 | -0.234 | -0.009 | 0.175 | -0.06 |

| As | 0.756 | 0.137 | -0.22 | -0.089 | 0.085 |

| Sr | 0.914 | 0.09 | 0.073 | 0.203 | 0.004 |

| Mo | -0.241 | 0.623 | 0.639 | -0.066 | -0.286 |

| Cd | 0.147 | 0.029 | -0.366 | 0.775 | -0.435 |

| Ba | 0.7 | -0.103 | 0.476 | 0.072 | -0.001 |

| Hg | 0.451 | -0.585 | 0.472 | 0.181 | 0.249 |

| Pb | -0.016 | 0.87 | 0.402 | 0.007 | 0.054 |

| Ca | 0.407 | 0.341 | 0.656 | 0.382 | -0.066 |

| K | 0.764 | 0.198 | -0.024 | -0.064 | 0.473 |

| Mg | 0.844 | 0.205 | -0.412 | -0.141 | 0.023 |

| Na | 0.748 | 0 | -0.425 | -0.147 | -0.218 |

| Characteristic Value | 6.02 | 4.69 | 3.165 | 2.867 | 1.246 |

| Contribution Rate | 28.668 | 22.331 | 15.071 | 13.653 | 5.934 |

| Cumulative Contribution | 28.668 | 50.999 | 66.07 | 79.724 | 85.658 |

| Discriminative Elements | RW | EW | OW |

|---|---|---|---|

| V | 324.172 | 277.182 | 1105.952 |

| Hg | 11.313 | 176.282 | -416.413 |

| Na | 4.846 | -10.191 | 86.957 |

| Cu | 1.414 | 6.211 | -30.246 |

| Constant | -25.954 | -74.715 | -160.480 |

| Method | Groups | Prediction Category | Discriminant Accuracy (%) | Comprehensive Discrimination Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RW | EW+PC | OW | ||||

| Stepwise Discrimination | RW | 4 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| EW+PC | 0 | 5 | 0 | 100.0 | ||

| OW | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100.0 | ||

| Cross Verification | RW | 4 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| EW+PC | 0 | 5 | 0 | 100.0 | ||

| OW | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100.0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).