Article Highlights

The regional and cultural differences of depression may suggests important implications to understand and prevent depression from a cultural perspective.

Confucian PST encourages individuals to actively recognize the meaning of adversity and maintain optimism when confronting setbacks.

Confucian PST not only directly mitigates depression and indirectly reduce depressive by enhancing adaptive cognition, improving behavior regulation and alleviating hopelessness feeling.

1. Introduction

Depression and other psychological problems showed a certain upward trend in different groups after the pandemic of COVID-19 (De France, et al., 2022; Galea., 2021). The regional and cultural differences of psychological problems have been reported in the previous studies (Lin et al., 2024, review). This may suggests important implications to understand and prevent psychological problems such as depression from a cultural perspective.

1.2. The Confucian PST and depression

A setback constitutes an interruption in goal pursuit caused by obstacles that delay or prevent desired outcomes, thereby resulting in goal disengagement or failure. Such interruptions often trigger emotional distress, expressed as depression in response to past failures and anxiety regarding future setbacks. However, some individuals actively seek out high-risk challenges, perceiving setbacks as growth opportunities. This reflects the spirit of the Chinese proverb, “One climbs the tiger’s mountain undeterred”. Chinese Confucian highlight the constructive role of setbacks in fostering self-improvement and overcoming perceived limitations. For instance, as Confucius (a Master of Confucianism) proposed in The Analects “Only in winter do we know the pine and cypress are the last to wither”. He framed adversity as a crucible that forges true courage. Similarly, Mencius (a Master of Confucianism) interpreted hardships as trials bestowed by Tian (Heaven) to strengthen an individual’s ability and character (Mencius). Neo-Confucian scholars such as Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi further systematized this view, advocating for composed self-reflection during setbacks to identify and rectify personal shortcomings in both behavior and ability (Shi & Zhao, 2014). Confucian philosophy advocates a cognitive reappraisal process wherein setbacks are reconstructed as developmental catalysts rather than ego-threatening events.

Contemporary scholarship has operationalized this thinking as “Pro-Setback Thinking” (PST), and defined it as a cognitive framework that: interprets hardships as catalysts for ability development and character cultivation, and fosters approach orientation toward challenges (Jing, 2006). Confucian PST includes two dimensions: an internal optimism toward setbacks (i.e., viewing frustrations as growth opportunities), and the positive meaning of setback or frustration. Confucianism, as one of the dominant traditional cultures in China, profoundly shapes Chinese personality traits and coping strategies under stress. Li and Chen’s (2021) cross-generational analysis revealed that parental PST positively predicts children’s PST, which in turn is associated with better mental health outcomes in children.

Numerous theoretical and empirical studies have suggested that cognitive styles affect the individual differences in depression risk after experiencing stressful life events (Zhou et al., 2014). Abramson et al. (1989) proposed cognitive vulnerability hypothesis in the theory of hopelessness depression that some people are at high risk for depression when negative or stressful events occur if they make stable and overall attributions for the causes of negative life events and/or infer that negative events will bring many catastrophic consequences and/or negative self-worth. Moreover, adaptive cognitive styles can facilitate recovery from depression and buffer the adverse effects of stressful life events (Needles & Abramson, 1990) . The strong empirical support for the cognitive vulnerability hypothesis was founded in the existing studies (Zhou et al., 2014).

Individuals with PST perceive setbacks as an inevitable part of life. When pursuing goals, if one can effectively accept, reflect upon, and learn from adversities, these challenges may facilitate the enhancement of competencies and moral character without undermining self-efficacy (Jing, 2006). Thus, although setbacks may cause by personal shortcomings, they would not lead to catastrophic consequences . The Confucian PST thereby helps individuals maintain emotional stability even in adversity ( Chen & Zhou, 2024). University students face multifaceted pressures including academic and interpersonal stressors, while simultaneously undergoing a developmental stage marked by greater behavioral autonomy and purposefulness. Consequently, the psychological impact of PST may be pronounced in this population. Based on these analyses, we propose Hypothesis 1 posits: Confucian PST is negatively associated with depression among university students.

1.3 The mediating role of hopelessness

Abramson et al. (1989) proposed a causal pathway for depression in the hopelessness theory, positing that hopelessness serves as the most proximal and sufficient cause in the etiological pathway of the disorder. According to this model, individuals who experience hopelessness will inevitably develop depression, though not all depressed individuals necessarily manifest hopelessness. Stress and cognitive vulnerability factors represent relatively distal factors within the etiological pathway. However, a growing body of empirical research indicates that these factors may not only indirectly elevate depression risk through the mediation of hopelessness but also directly increase an individual’s risk for depression (Gotlib & Joormann,2010; Slavich & Irwin, 2014; Villalobos et al., 2021 ). Therefor, logically, Confucian PST may also be associated with depression through the mediating role of hopelessness.

A key determinant of hopelessness is the perceived futility of effort - the belief that one's efforts will neither yield desired outcomes nor prevent the occurring of adverse events. The Confucian philosophy of adversity advocates for individuals to recognize and embrace the intrinsic value of setbacks in personal development (Zhou & Chen, 2024). The Confucian PST encourages individuals to recognize the value of setbacks, as these experiences contribute to the fulfillment of one's cardinal responsibilities: self-cultivation, family regulation , state governance, and universal peace (The Great Learning). This cognitive style is both goal-directed and problem-solving orientated (Li & Hou, 2012). Empirical evidence indicates that PST serves a protective role by preventing the formation of hopelessness following adverse experiences, thereby reducing vulnerability to depressive (Chen & Chen, 2024). We propose Hypothesis 2 that hopelessness mediates the association between Confucian PST and depressive among university students.

1.4. The mediating role of self-control

Self-control is an ability to autonomously regulate one’s behaviors, thoughts, and emotions in alignment with personal or social values (Tan & Guo, 2008). It is integral to adaptive behavior, goal-directed behaviors and serves as a critical protective factor for mental health (Butterworth et al., 2022; Ge & Hou, 2021; Shi & Ma, 2021). Job et al (2010) and Job et al (2015) proposed that subjective beliefs have an important impact on psychological resources and self-control behaviors according to the Ego Depletion Theory Model. Those who perceive their willpower as limited are more susceptible to ego depletion effects, exhibiting subsequent declines in self-control performance, whereas individuals who maintain confidence in their willpower resources demonstrate resilience against such depletion effects, preserving behavioral regulation capacities.

The Confucian PST is grounded in the interdependent system of goals encompassing “self-cultivation, household regulation, state governance, and world pacification (The Great Learning)”. The aims of it is to encourage individuals to “shoulder weighty mission and keep enduring perseverance (Confucian)” and “unbowed by force, unswayed by poverty (Mencius)”, emphasizing persistent goal-directed behavior with firm will in ultimate success. The Confucian PST facilitates the maintenance of self-control and self-efficacy through cognitive reappraisal that reduces the perceived threat of setbacks, thereby minimizing ego depletion and preventing emotionally driven abandonment of goals. That is, “the brave are not afraid (Confucius, Analects)”,individuals with the Confucian PST tend to prioritize long-term goal-directed behaviors over immediate adversities. Ge and Hou's (2021) found that individuals embodying the Confucian junzi (the ideal personality of Confucianism) demonstrate enhanced self-control. Therefore, based on the characteristics of self-control, we proposes Hypothesis 3: Self-control mediates the relationship between Confucian PST and depression among university students.

1.5. The chain mediating path from self-control to hopelessness

Recent empirical evidence demonstrates that impaired self-regulatory efficacy significantly predicts elevated hopelessness (Katherine & Veilleux, 2024). The Confucian meaning reconstruction of adversity facilitates more balanced appraisal of both short- and long-term impacts of setbacks, thereby attenuating their perceived threat of setbacks. The intrinsic optimism of Confucian PST can promote individuals sustains future-oriented hope and reduce catastrophizing cognitions. From the perspective of the causal chain of hopelessness depression, such positive meaning attribution reduces stress perceived, and internal optimism buffers against hopelessness by mitigating tendencies toward catastrophic consequence and self-worth devaluation (Zhou et al., 2014). The synergistic effect of these mechanisms not only facilitates the maintenance of goal-directed behaviors but also enhances individuals' sense of control over both their actions and outcomes. Consequently, the PST may associated depression through two distinct pathways: by enhancing self-control (or self-regulation behavior) and by reducing susceptibility to hopelessness. Furthermore, according to Self-Determination Theory, when individuals perceive strong self-efficacy and control over their behaviors, their basic psychological needs are more likely to be satisfied (Ryan &Deci , 2017), thereby substantially decreasing the probability of hopelessness. Collectively, individuals with PST tend to maintain self-control across situations through adaptive interpretations of setbacks and internal optimism, with an associations to reduced hopelessness and depression. Based on these relationships among these variables, we proposes Hypothesis 4: self-control and hopelessness sequentially mediate the association between PST and depression among university students.

1.6. The present study

Confucianism serves as a foundational cultural framework that systematically shapes personality among Chinese individuals (Shi & Zhao, 2014). From the causal chain proposed by the hopelessness depression theory (Abramson et al., 1989), Confucian PST may associate with depression through multiple indirect paths. This study investigates the psychological protective effect of Confucian PST against depression among Chinese university students: (1) the direct correlation between Confucian PST and depression; (2) the independent mediating roles of self-control and hopelessness in this association; and (3) the sequential mediation pathway of self-control and hopelessness in this association.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

The investigation was conducted online using convenience sampling in a university of Hunan Province, the central area of China. A total of 1225 questionnaires were collected, questionnaires with more than five missing items or patterned responses were excluded from analysis, 996 valid questionnaires aging from 18 to 22 years old (M=18.22, SD=0.75) were obtained for an effective response rate of 81.31%. Among them, 717 (72.00%) were male, and 279 were female. Informed consent were obtained from all participants.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. PST

The two subscales, “optimism in the adversity” and “the meaning of adversity to individual growing” of the 15-item Confucian Coping questionnaire were used (Jing, 2006) to measure the PST of college students. The “optimism in the adversity” subscale consisted of 4 items, including “Even when I am at my worst, I feel hopeful for the future”. “The meaning of adversity to individual growing” subscale consisted of 4 items, including “Without suffering, there will be no tenacious will”. A 5-point scale was used in the two subscales. The sum of all item scores was the total PST score, with higher scores indicating higher PST. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the two subscales was 0.85.

2.2.2. Depression

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used to measure the depression of college students. The DASS-21 is a 21-item questionnaire validated in the Chinese population (Gong et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2021). Depression subscale is implemented to estimate anhedonia, inertia, self-deprecation, and devaluation of life (e.g., I felt that I had nothing to look forward to). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “did not apply to me”, 3 = “applied to me very much of the time”) and high subscale scores indicate high levels of depression. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of depression subscale was 0.82.

2.2.3. Self-control

The Chinese version of the Self-Control Scale (Tangney et al., 2004), translated and revised by Tan and Guo (2008), was used. The scale consisted of 19 items, including “I can resist temptation very well” and “I easily lose my temper”. A 5-point scale was used. The scale is applicable to Chinese university students and has good reliability (Ge & Hou, 2021). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.80.

2.2.4. Hopelessness

The Chinese version of the Beck Hopelessness Scale ( Beck et al., 1974), translated and revised by Xin et al (2006), was used to measure pessimistic expectations or negative attitudes towards the future of college students. The scale consists of 20 items, and participants are required to answer “yes” or “no”. Pessimistic statements about the future were assessed by 11 items, such as“My future is in darkness” . Answering “yes”scored as 1. The other 9 items are optimistic statements about the future, such as “I have enough confidence that I can achieve my ideals in the future.” Answering “no”scored as 1. The sum of all item scores was the total hopelessness score, with higher scores indicating higher hopelessness. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.79.

2.3. Data analysis

The SPSS Version 22.0 was used for descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. First, we computed mean and standard deviation of each variable. The Pearson’s correlation analysis was then applied to detect the correlation between variables. Third, we performed chain mediation analyses with Bootstrap analysis to examine the mediating roles of self-control and hopelessness in the relationship between PST and depression, using the PROCESS macro program Version 3.5 (Hayes, 2018). We used 5000 bootstrap samples, and biases were corrected at 95% confidence intervals to calculate the indirect effect of each variable.

2.4. Common Method Biases Test

Due to the reliance on self-reported data, this study may be subject to common method bias. To assess potential common method bias, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test. The analysis extracted 12 factors with eigenvalues >1, collectively explaining 54.25% of the total variance. The first factor accounted for 24.69% of the variance (below the 40% threshold), indicating no severe common method bias in our data (Tang & Wen, 2020).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presented the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results for each variable. Confucian PST positively correlated with self-control and negatively with hopelessness and depression. Self-control negatively correlated with hopelessness and depression, whereas hopelessness positively correlated with depression.

3.2. Mediation model testing analysis

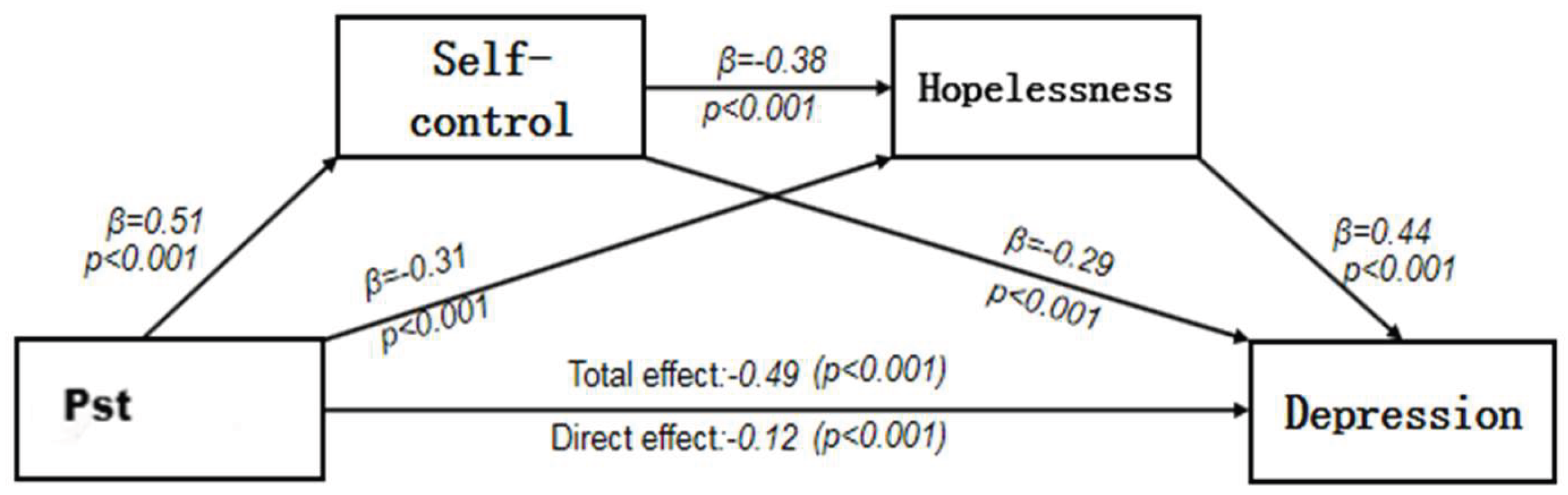

Multiple mediation analysis was performed using PROCESS macro (Model 6) to examine the multiple mediating effects among the four variables. PST was used as the independent variable; depression as the dependent variable; self-control and hopelessness as mediating variables, gender and age as control variables. All variables in the model have been standardized, except for gender. Gender was dummy-coded as 0 for male and 1 for female. The results of regression analysis showed (see

Table 2): PST showed significant negative connection with depression (

β=-0.48,

p<0.001) and hopelessness(

β=-0.31,

p<0.001); but a significant positive correlation with self-control (

β=0.51,

p<0.001); self-control was negatively related with both hopelessness (

β=-0.38,

p<0.001) and depression (

β=-0.29,

p<0.001); hopelessness positively connected with depression(

β=0.44,

p<0.001). Bootstrap sampling method was used to test the mediating role. The path coefficient results were shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 3. Self-control and hopelessness mediated significantly the relationship between PST and depression, with a total standardized mediation effect value of -0.37, accounting for 75.51% of the total effect coefficient of the correlation between PST and depression. Three significant mediating chains were identified in this study: Firstly, mediating effect coefficient 1 (-0.15) generated by Path 1 of “PST → self-control → depression”, accounting for 30.61% of the total effect; Secondly, mediating effect coefficient 2 (-0.13) generated by Path 2 of “PST →hopelessness→ depression”, accounting for 26.53% of the total effect coefficient; Thirdly, mediating effect coefficient 3 (-0.09) generated by Path 3 of “PST→ self-control→ hopelessness→ depression,” accounting for 18.37% of the total effect coefficient. The 95% CI of the above three paths did not contain a 0 value, indicating that the three indirect effects coefficient have reached a significant level.

Discussion

Guided by the causal path proposed in the hopelessness theory of depression, this investigation explored the protective pathways linking Confucian PST to depression among Chinese undergraduates. Consistent with Hypothesis 1 and prior findings (Chen & Zhou, 2024; Li & Hou,2012), results revealed that Confucian PST was significantly negatively associated with depressive. Dixon et al. (2018) also found that individuals’ positive perceptions of setbacks positively affect their positive emotions when faced with setbacks. We propose that the Confucian PST may mitigate depression risk through two psychological mechanisms. The Confucian PST emphasizes that setbacks are unavoidable. By reappraising challenges as growth opportunities instead of threats, people can effectively lower their stress perception. Second, the internal optimism embedded in this thinking helps individuals maintain the belief that while setbacks may have temporary negative consequences, they do not necessarily predict permanent impairment to future goals or self development, a cognitive buffer against catastrophizing tendencies. Overall, Confucian PST is a relatively flexible cognitive style. Brouder and Haeffell (2023) founded that unchangeability or inflexibility of cognition is an important risk factor for depression in undergraduates by longitudinal investigation (Brouder & Haeffell, 2023; Stange, et al., 2017).

The mediation analyses of this study revealed that hopelessness significantly mediated the relationship between Confucian PST and depressive among undergraduates, supporting hypothesis 2. Hopelessness makes individual gives up their efforts and they feel there is no hope of changing the current situation, because their behaviors did not lead to the desired outcome, and the undesirable outcome cannot be avoided (Zhou, et al., 2014). Individuals with PST exhibit lower hopelessness and depression risk through integrated cognitive-behavioral mechanisms. Cognitively, PST fosters adaptive attributions by reframing setbacks as controllable and temporary not stable-global appraisals, while maintaining self-efficacy through growth-oriented meaning-making. Behaviorally, PST promotes active problem-solving and failure-based learning, reinforcing goal-oriented activities and preventing behavioral withdrawal. According to the hopelessness theory of depression, the dual-pathway explains protective effects the PST across cognitive and behavioral dimensions of hopelessness and depression vulnerability.

The mediation role of self-control between Confucian PST and depressive symptoms among college students was founded in this study, supporting hypothesis 3. This finding aligns with established evidence that self-control functions as a psychological resource that enhances physical and mental health outcomes (Cheung et al., 2014). Existing research indicates that individuals with greater self-control demonstrate higher levels of self-authenticity, which is positively associated with mental health outcomes (Kokkoris et al., 2019; Ge & Hou, 2021). Yang (2018) identifies self-control as the foundational capacity required for actualizing “spiritual initiative” , which is the Confucian ideal of autonomous moral volition that persists despite external adversities. Chen and Zhou (2024) also found that Confucian PST was positively associated with self-control. The Confucian PST guides individuals to persist in goal-directed behaviors by reducing reliance on external rewards and impulsive reactions. More importantly, this mindset serves as a psychological buffer that mitigates the negative impact of setbacks on self-efficacy. When individuals maintain a sense of competence after experiencing adversity, they are better able to preserve behavioral autonomy and sustain goal-oriented actions in subsequent tasks. Therefore, individuals with Confucian PST tend to demonstrate stronger self-control that facilitates behavioral alignment with sociocultural expectations, thereby enhancing perceived belonging and validation while reducing depression vulnerability.

The present findings further substantiate a sequential mediation pathway wherein self-control and hopelessness serially mediate the association between Confucian PST and depressive symptoms, thereby fully supporting Hypothesis 4. This demonstrates that Confucian PST connect with depression through a chain path: Confucian PST first enhances goal-orientation behavioral (self-control), which subsequently reduces hopelessness, thereby ultimately decreasing depression. The chain mediating model revealed a comparable effect sizes of four different pathways connecting Confucian PST to reduced depression. This approximately equal weighting of four pathway effects suggests that Confucian PST functions as an multi-dimensional buffer against depression. It facilitates adaptive setback reappraisal (cognitive), enhances behavioral self-regulation (behavioral), and reduces hopelessness (affective). The current findings empirically validate, from the perspective of hopelessness theory, that cultivating Confucian PST in undergraduates can reduce depression through multiple pathways. This multi-faceted protective effect underscores the value of developing targeted psychological intervention programs based on these mechanisms.

This study, grounded in the hopelessness theory of depression, infers causal pathways among variables with inherent methodological limitations. Future research should employ longitudinal designs or psychological intervention experiments to rigorously test these causal relationships. Subsequent research should examine the cross-cultural generalizability of the proposed relational pathways in this study.

Conclusions

Confucian PST negatively correlated with depression among college students, mediated separately by self-control and hopelessness. These mediators also played a chain mediating role between Confucian PST and depression.

References

- Abramson, L. Y. , Metalsky, F. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory based subtype of depression. Psychol Rev, 96, 358–372. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T. , Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Cons & Clin Psycho. 42, 861–865. [CrossRef]

- Brouder, L. M. , & Haeffel, G. J. (2023). Stable-global attributions, but not emotional valence, predict future depressive symptoms and event-specific inferences. J Soc Clin Psycho, 42, 16.

- Butterworth, J. W. , Finley, A. J., Baldwin, C. L., & Kelley, N. J. (2022). Self-control mediates age-related differences in psychological distress. Persy Indiv Differ, 184, 111137. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , & Chen, S. Y. (2024). On Relationship between Pro-setbacks and Depression: The Role of Hopelessness and Ego-depletion. J Hengyang Norm Univ(Nat Sci), 45(6), 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , & Zhou, L. H. (2024). Effect of pro-setback thinking on depression, anxiety, stress in college students: Chain mediating effect. China J Health Psychol, 32(4),627-634.

- Cheung, T. T. , Gillebaart, M., Kroese, F., & De Ridder, D. (2014). Why are people with high self-control happier? The effect of trait self-control on happiness as mediated by regulatory focus. Front Psychol, 5, 722. [CrossRef]

- De France K, Hancock G. R., Stack, D. M., Serbin, L. A., & Hollenstein, T. (2022).

- The mental health implications of COVID-19 for adolescents: follow-up of a four-wave longitudinal study during the pandemic. The American Psychol, 77, 85–99. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M. J. , Larche, C. J., Stange, M., Graydon, C., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2018). Near-misses and stop buttons in slot machine play: An investigation of how they affect players, and may foster erroneous cognitions. J Gambl Stud 34, 161–180. [CrossRef]

- Galea, S. , & Ettman, C. K. (2021). Mental health and mortality in a time of COVID-19. Americal J Publ Health, 111, 73–74. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Y. , & Hou, Y. B. (2021). A gentleman does not worry or fear: a Gentleman's personality and mental health: chain mediation of self-control and authenticity. Act Psychol. Sinc, 53(4), 374–386. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X. , Xie, X. Y., Xu, R., & Luo, Y. J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chinese J Clin Psychol, 18(04), 443-446. [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, I. H. , and Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6, 285–312. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hyun, M. H. , & Kwon, Y. S. (2014). Relationship between Sense of Self-control, Hopelessness, Perceived Support from Family, and Suicidal Ideation in Alcohol Use Disorders. The Korean J Health Psychol, 19, 585-601.

- Jing, H. B. (2006). Confucian coping and its role to mental health. Act Psychol Sinc, 38, 126-134 CNKI:SUN:XLXB.0.2006-01-017.

- Job, V. , Dweck, C. S., & Walton, G. M. (2010). Ego depletion--is it all in your head? implicit theories about willpower affect self-regulation. Psychol Sci 21, 1686-1693. [CrossRef]

- Job, V. , Walton, G. M., Bernecker, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Implicit theories about willpower predict self-regulation and grades in everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol 108(4), 637-647. [CrossRef]

- Katherine, H. B. M. A. , & Veilleux, J. C. (2024). Examining state self-criticism and self-efficacy as factors underlying hopelessness and suicidal ideation. Suicide Life -Threat Behav 54(2), 207-220. [CrossRef]

- Kokkoris, M. D. , Hoelzl, E., & Alós-Ferrer, C. (2019). True to which self? Lay rationalism and decision satisfaction in self-control conflicts. J Pers Soc Psycho 117, 417-447. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. M. , & Chen, Y. (2021). Intergenerational transmission of Confucian coping and the effect on children’s mental health, J Southwest Jiaotong Univ, 22(5), 17-24.

- Li, T. R. , & Hou, Y. B. (2012). Psychological structure and psychometric validity of the Confucian Coping. J Edu Sci Hunan Norm Univ 11, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. K. , Saragih, I. D., Lin, C. J., Liu, H. L., Chen, C. W., & Yeh, Y. S. (2024). Global prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol 12, 388. [CrossRef]

- Needles, D. J. , & Abramson, L. Y. (1990). Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnorm Psychol 99(2), 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. M. A. , Mohammad, D., Qureshi, M.F.H., Abbas, M. Z., & Aleem, S. (2021). Prevalence, Psychological Responses and Associated Correlates of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in a Global Population, During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Comm Ment Health J, 57, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M. , & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Shi, M.W. , & Zhao, S. Y.(2014) Confucianism and Stress Management: Stress Study from the Chinese Perspective, J Nanjing Norm Univy (Soc Sci Edit), 2, 117-122.

- Shi, Y. H. , & Ma, C. (2021). The influence of trait anxiety on middle school Students' academic performance: the mediation between sense of life meaning and self control. Chinese J Spec. Edu. 10, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G. M. , & Irwin, M. R. (2014). From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin 140(3), 774-815. [CrossRef]

- Stange, J. P. , Alloy, L. B., and Fresco, D. M. (2017). Inflexibility as a vulnerability to depression: a systematic qualitative review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 24 245–276. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S. H. , & Guo, Y. (2008). Revision of self-control scale for Chinese college students. Chinese J Clin Psychol 16, 468-470. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. D. , & Wen, Z. L. (2020). Statistical Approaches for Testing Common Method Bias: Problems and Suggestions. J Psychol Sci 43, 215-223. [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P. , Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers, 72, 271-322. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos D, Pacios J and Vázquez C (2021) Cognitive Control, Cognitive Biases and Emotion Regulation in Depression: A New Proposal for an Integrative Interplay Model. Front. Psychol 12:62, 8416. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z. Q. , Ma, J. X., & Geng, L. N. (2006). Relationships Between Adolescents’ Hopelessness and Life Events, Control Beliefs and Social Supports. Psychol Dev Edu, 22 6, 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. H. (2018). One origin and endless changes: Essentials of monism of principles. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

- Zhou, L. H. , Chen, J., Lu D. L., Liu, X. Q., & Su, L. Y. (2014). Hopelessness and Hopefulness: Risk and Resilience to Hopelessness Depression from the Perspective of Cognitive Style, Adv Psychol Sci, 22 (6), 977–986. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).