Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive Psychology Interventions to Promote Optimism and Well-Being

1.2. Aim and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aknin, L. B., De Neve, J.-E., Dunn, E. W., Fancourt, D. E., Goldberg, E., Helliwell, J. F., Jones, S. P., Karam, E., Layard, R., Lyubomirsky, S., Rzepa, A., Saxena, S., Thornton, E. M., VanderWeele, T. J., Whillans, A. V., Zaki, J., Karadag, O., & Ben Amor, Y. (2022). Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(4), 915–936. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Manual de Publicaciones de la APA. El Manual Moderno.

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu Izaguirre, L., Fernández, A. R., & Palacios, E. G. (2021). Adolescent Life Satisfaction Explained by Social Support, Emotion Regulation, and Resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694183. [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2019). Unhappiness and Pain in Modern America: A Review Essay, and Further Evidence, on Carol Graham’s Happiness for All? Journal of Economic Literature, 57(2), 385–402. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I., Contreras, A., Chaves, C., Lopez-Gomez, I., Hervas, G., & Vazquez, C. (2020). Positive interventions in depression change the structure of well-being and psychological symptoms: A network analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 623–628. [CrossRef]

- Boggio, P. S. (2019). Science and education are essential to Brazil’s well-being. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(7), 648–649. [CrossRef]

- Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 119. [CrossRef]

- Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 749–769. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 879–889. [CrossRef]

- Cefai, C., Camilleri, L., Bartolo, P., Grazzani, I., Cavioni, V., Conte, E., Ornaghi, V., Agliati, A., Gandellini, S., Tatalovic Vorkapic, S., Poulou, M., Martinsone, B., Stokenberga, I., Simões, C., Santos, M., & Colomeischi, A. A. (2022). The effectiveness of a school-based, universal mental health programme in six European countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925614. [CrossRef]

- Chakhssi, F., Kraiss, J. T., Sommers-Spijkerman, M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2018). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 211. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361–368. [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., Quinn, A., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Griffin, B. J., & Worthington, E. L. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 20–31. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., Zhang, J., Chen, H., Tian, S., Zhang, Y., & Hu, X. (2024). Benefiting Individuals High in Both Self-Criticism and Dependency Through an Online Multi-component Positive Psychology Intervention: Effects and Mechanisms. Journal of Happiness Studies, 25(1–2), 16. [CrossRef]

- Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using Gratitude to Promote Positive Change: A Series of Meta-Analyses Investigating the Effectiveness of Gratitude Interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260. [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376. [CrossRef]

- García-Carrión, R., Villarejo-Carballido, B., & Villardón-Gallego, L. (2019). Children and Adolescents Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Interaction-Based Interventions in Schools and Communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 918. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. M., Yasinski, C., Ben Barnes, J., & Bockting, C. L. H. (2015). Network destabilization and transition in depression: New methods for studying the dynamics of therapeutic change. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J., & Neve, J. E. D. (n.d.). World Happiness Report 2020. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network. https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2020/.

- Hendricks, S., Sin, D. W., Van Niekerk, T., Den Hollander, S., Brown, J., Maree, W., Treu, P., & Lambert, M. (2020). Technical determinants of tackle and ruck performance in International Rugby Sevens. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(7), 868–879. [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E., Mayal, E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & Van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00278-3/fulltext?ref=f-zin.faktograf.hr.

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2021). Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(1), 23–34. [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F. A. (2009). A New Approach to Reducing Disorder and Improving Well-Being. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(1), 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Joutsenniemi, K. (2014). E-mail-based Exercises in Happiness, Physical Activity and Readings: A Randomized Trial on 3274 Finns. Journal of Psychiatry, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- Kalamatianos, A., Kounenou, K., Pezirkianidis, C., & Kourmousi, N. (2023). The Role of Gratitude in a Positive Psychology Group Intervention Program Implemented for Undergraduate Engineering Students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 460. [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. [CrossRef]

- Kounenou, K., Kalamatianos, A., Garipi, A., & Kourmousi, N. (2022). A positive psychology group intervention in Greek university students by the counseling center: Effectiveness of implementation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 965945. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L., Passmore, H.-A., & Joshanloo, M. (2019). A Positive Psychology Intervention Program in a Culturally-Diverse University: Boosting Happiness and Reducing Fear. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1141–1162. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L., Warren, M. A., Schwam, A., & Warren, M. T. (2023). Positive psychology interventions in the United Arab Emirates: Boosting wellbeing – and changing culture? Current Psychology, 42(9), 7475–7488. [CrossRef]

- Layous, K., Chancellor, J., Lyubomirsky, S., Wang, L., & Doraiswamy, P. M. (2011). Delivering Happiness: Translating Positive Psychology Intervention Research for Treating Major and Minor Depressive Disorders. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(8), 675–683. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. (2022). Analysis on the literature communication path of new media integrating public mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 997558. [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied Positive Psychology: Integrated Positive Practice. SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Han, J., & Smith, S. (2024). Exploring Chinese EMI lecturers’ pedagogical engagement through the lens of culturally informed positive psychology: An intervention study. System, 125, 103444. [CrossRef]

- Magnano, P., Paolillo, A., & Giacominelli, B. (2015). Dispositional Optimism as a Correlate of Decision-Making Styles in Adolescence. SAGE Open, 5(2), 215824401559200. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2020, September). Distributional Effects of COVID-19 on Spending: A First Look at the Evidence from Spain. Barcelona GSE Graduate School of Economics; Working Paper no 1201. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://bse.eu/sites/default/files/working_paper_pdfs/1201.pdf.

- Nguyen, T. T. P., Nguyen, T. T., Dam, V. T. A., Vu, T. T. M., Do, H. T., Vu, G. T., Tran, A. Q., Latkin, C. A., Hall, B. J., Ho, R. C. M., & Ho, C. S. H. (2022). Mental wellbeing among urban young adults in a developing country: A Latent Profile Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 834957. [CrossRef]

- Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (n.d.). An applied framework for positive education.

- OECD. (2020). How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en. [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S., & Diener, Ed, E. (2021). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (3rd ed., pp. 255–264): Vol. 3rd ed., pp. 255–264. Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, C., Semmel, A., Von Baeyer, C., Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1982). The attributional Style Questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6(3), 287–299. [CrossRef]

- Phan, K., Jennings, L., & Gloeckner, G. (2025). Fostering First-Year Student Retention in Vietnam: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of a Positive Psychology-Based College Readiness Intervention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15210251251320373. [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, M. E., Morton, D. P., Morton, J. K., & Przybylko, G. (2021). The Influence of Human Support on the Effectiveness of Digital Mental Health Promotion Interventions for the General Population. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 716106. [CrossRef]

- Salois, D. J. (n.d.). PROMOTING WELL-BEING AMONG COLLEGE STUDENTS: THE EFFECTS OF A POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY COURSE [Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11799]. Retrieved 15 December 2024, from https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11799.

- Sanilevici, M., Reuveni, O., Lev-Ari, S., Golland, Y., & Levit-Binnun, N. (2021). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Increases Mental Wellbeing and Emotion Regulation During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Synchronous Online Intervention Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720965. [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–24747. [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C., Sampaio, F., Pinho, L. G. D., Araújo, O., Lluch Canut, T., & Sousa, L. (2022). Editorial: Mental health literacy: How to obtain and maintain positive mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1036983. [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, T., Sifelani, I., Kwembeya, M., Matsikure, M., & Songo, S. (2022). Attitudes and perceptions of teachers toward mental health literacy: A case of Odzi High School, Mutare District, Zimbabwe. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1003115. [CrossRef]

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. [CrossRef]

- Siriaraya, P., Tanaka, R., She, W. J., Jain, R., Schok, M., De Ruiter, M., Desmet, P., & Nakajima, S. (2024). Happy Click!: Investigating the Use of a Tangible Interface to Facilitate the Three Good Things Positive Psychology Intervention. Interacting with Computers, 36(4), 240–254. [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G. R., Lee, M. A., & Mossman, L. H. (2021). Interventions to support autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs in organizations: A systematic review with recommendations for research and practice. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(2), 427–457. [CrossRef]

- Talić, I., Winter, W., & Renner, K.-H. (2023). What Works Best for Whom?: The Effectiveness of Positive Psychology Interventions on Real-World Psychological and Biological Stress and Well-Being Is Moderated by Personality Traits. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 231(4), 252–264. [CrossRef]

- The state of happiness in a COVID world (Informe de Encuesta Global Happiness 2020). (2020). Ipsos Global Advisor. https://www.ipsos.

- Trigueros, R., Padilla, A. M., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Rocamora, P., Morales-Gázquez, M. J., & López-Liria, R. (2020). The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Resilience, Test Anxiety, Academic Stress and the Mediterranean Diet. A Study with University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2071. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. (2021). The State of the World’s Children 2021: On My Mind – promoting, protecting and caring for children’s mental health. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

- Van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(5), 631–652. [CrossRef]

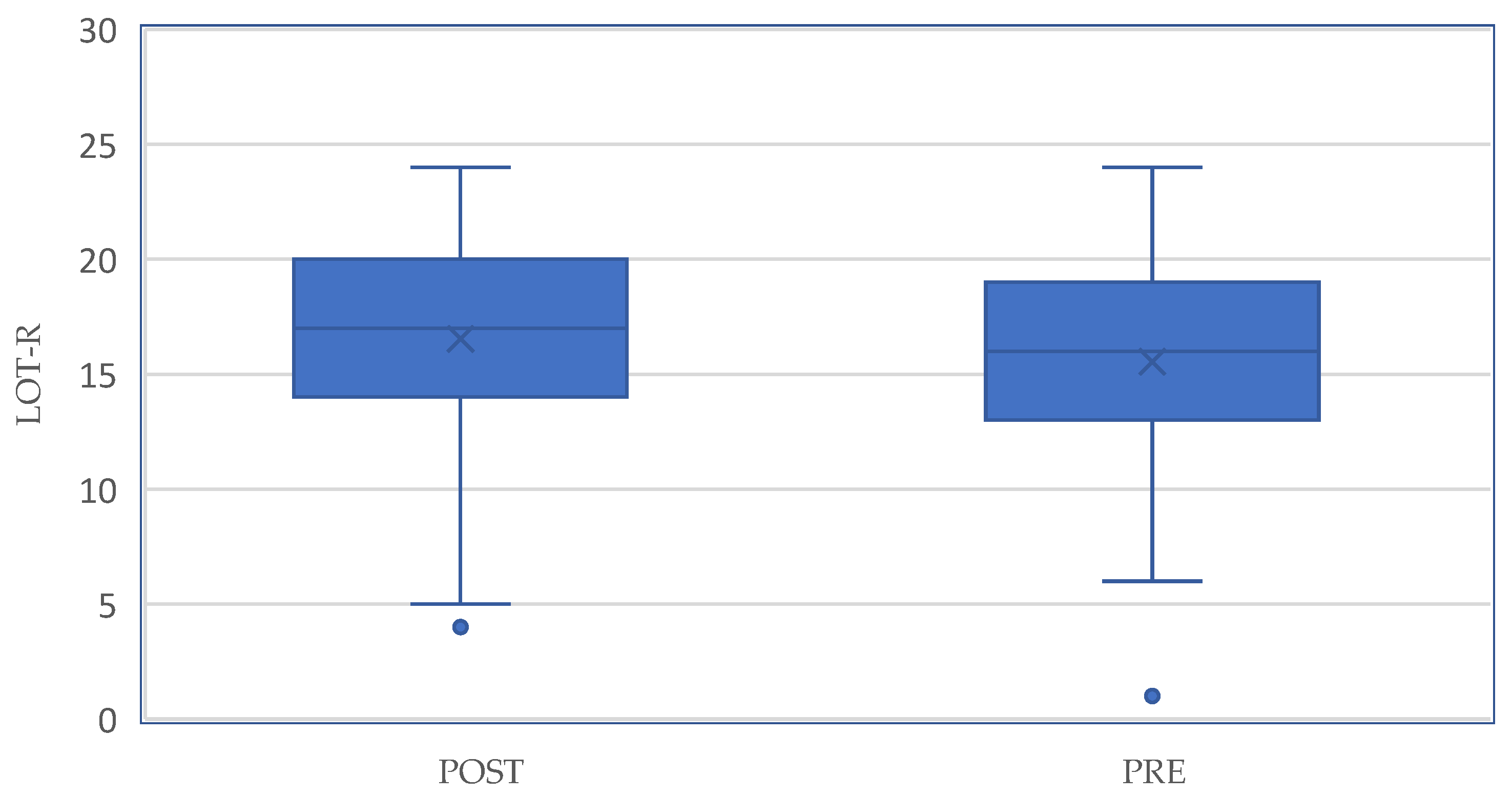

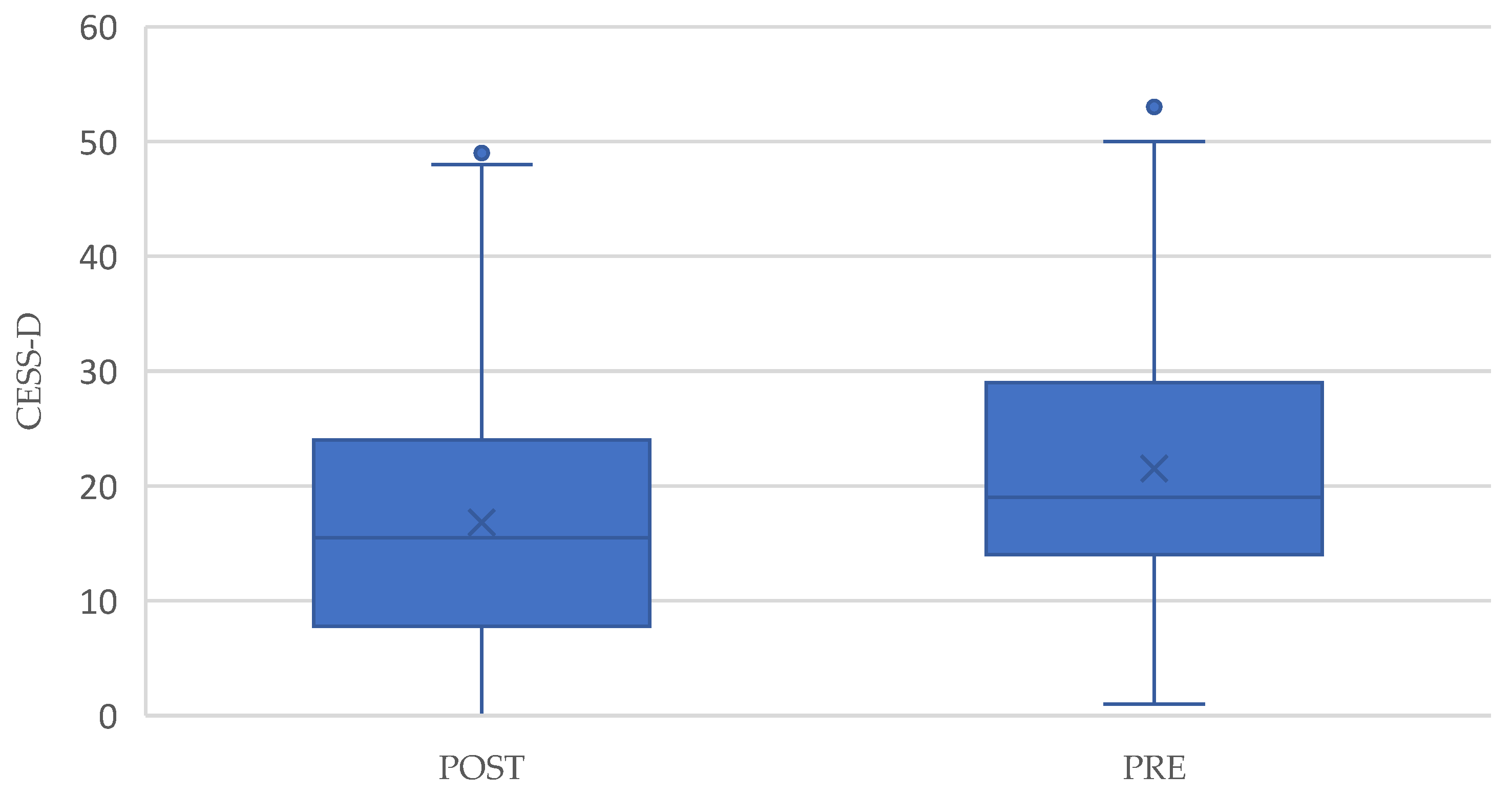

| N=136 | LOT-R | CESS-D | GRIT | PvG |

| Mann-Whitney U | 2388.500 | 2383.500 | 2030.000 | 2647.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 4734.500 | 4729.500 | 4376.000 | 4993.500 |

| Test Statistic | 2388.500 | 2383.500 | 2030.000 | 2647.500 |

| Standard Error | 229.171 | 229.640 | 228.605 | 224.675 |

| Standardized Test Statistic | .334 | .311 | -1.234 | 1.493 |

| Asymptotic Sig.(2-sided test) | .739 | .756 | .217 | .135 |

| N=136 | PsB | HoB | PvB | PmG |

| Mann-Whitney U | 2255.500 | 2557.000 | 2660.000 | 2239.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 4601.500 | 4903.000 | 5006.000 | 4585.000 |

| Test Statistic | 2255.500 | 2557.000 | 2660.000 | 2239.000 |

| Standard Error | 226.044 | 227.001 | 223.795 | 223.224 |

| Standardized Test Statistic | -.250 | 1.079 | 1.555 | -.327 |

| Asymptotic Sig.(2-sided test) | .803 | .280 | .120 | .744 |

| N=136 | PmB | PsG |

| Mann-Whitney U | 2378.000 | 2330.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 4724.000 | 4676.000 |

| Test Statistic | 2378.000 | 2330.000 |

| Standard Error | 222.786 | 223.275 |

| Standardized Test Statistic | .296 | .081 |

| Asymptotic Sig.(2-sided test) | .767 | .936 |

| PsG | PmB | PmG | PvB | HoB | PsB | PvG | GRIT | CESS-D | LOT-R | ||||

| PsG | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | -.089 | .163** | -.104 | .055 | -.201** | .192** | -.018 | -.239** | .174** | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | . | .158 | .009 | .101 | .385 | .001 | .002 | .771 | <.001 | .006 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| PmB | Correlation Coefficient | -.089 | 1.000 | -.019 | .148* | .644** | .165** | -.099 | .092 | .140* | -.115 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .158 | . | .764 | .018 | <.001 | .009 | .117 | .146 | .026 | .067 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| PmG | Correlation Coefficient | .163** | -.019 | 1.000 | -.118 | .011 | -.098 | .092 | .025 | -.167** | .024 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .009 | .764 | . | .062 | .864 | .121 | .146 | .693 | .008 | .703 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| PvB | Correlation Coefficient | -.104 | .148* | -.118 | 1.000 | .579** | .016 | -.058 | -.047 | -.025 | .058 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .101 | .018 | .062 | . | <.001 | .804 | .359 | .454 | .697 | .360 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| HoB | Correlation Coefficient | .055 | .644** | .011 | .579** | 1.000 | -.079 | .083 | .152* | .029 | -.061 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .385 | <.001 | .864 | <.001 | . | .209 | .191 | .016 | .650 | .333 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| PsB | Correlation Coefficient | -.201** | .165** | -.098 | .016 | -.079 | 1.000 | -.242** | -.073 | .040 | -.029 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .009 | .121 | .804 | .209 | . | <.001 | .248 | .527 | .649 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| PvG | Correlation Coefficient | .192** | -.099 | .092 | -.058 | .083 | -.242** | 1.000 | .135* | -.104 | .092 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | .117 | .146 | .359 | .191 | <.001 | . | .032 | .099 | .144 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| GRIT | Correlation Coefficient | -.018 | .092 | .025 | -.047 | .152* | -.073 | .135* | 1.000 | .074 | .025 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .771 | .146 | .693 | .454 | .016 | .248 | .032 | . | .243 | .694 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| CESS-D | Correlation Coefficient | -.239** | .140* | -.167** | -.025 | .029 | .040 | -.104 | .074 | 1.000 | -.550** | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <.001 | .026 | .008 | .697 | .650 | .527 | .099 | .243 | . | <.001 | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| LOT-R | Correlation Coefficient | .174** | -.115 | .024 | .058 | -.061 | -.029 | .092 | .025 | -.550** | 1.000 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .006 | .067 | .703 | .360 | .333 | .649 | .144 | .694 | <.001 | . | |||

| N | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | 252 | |||

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||||||||||||

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | |||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).