Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

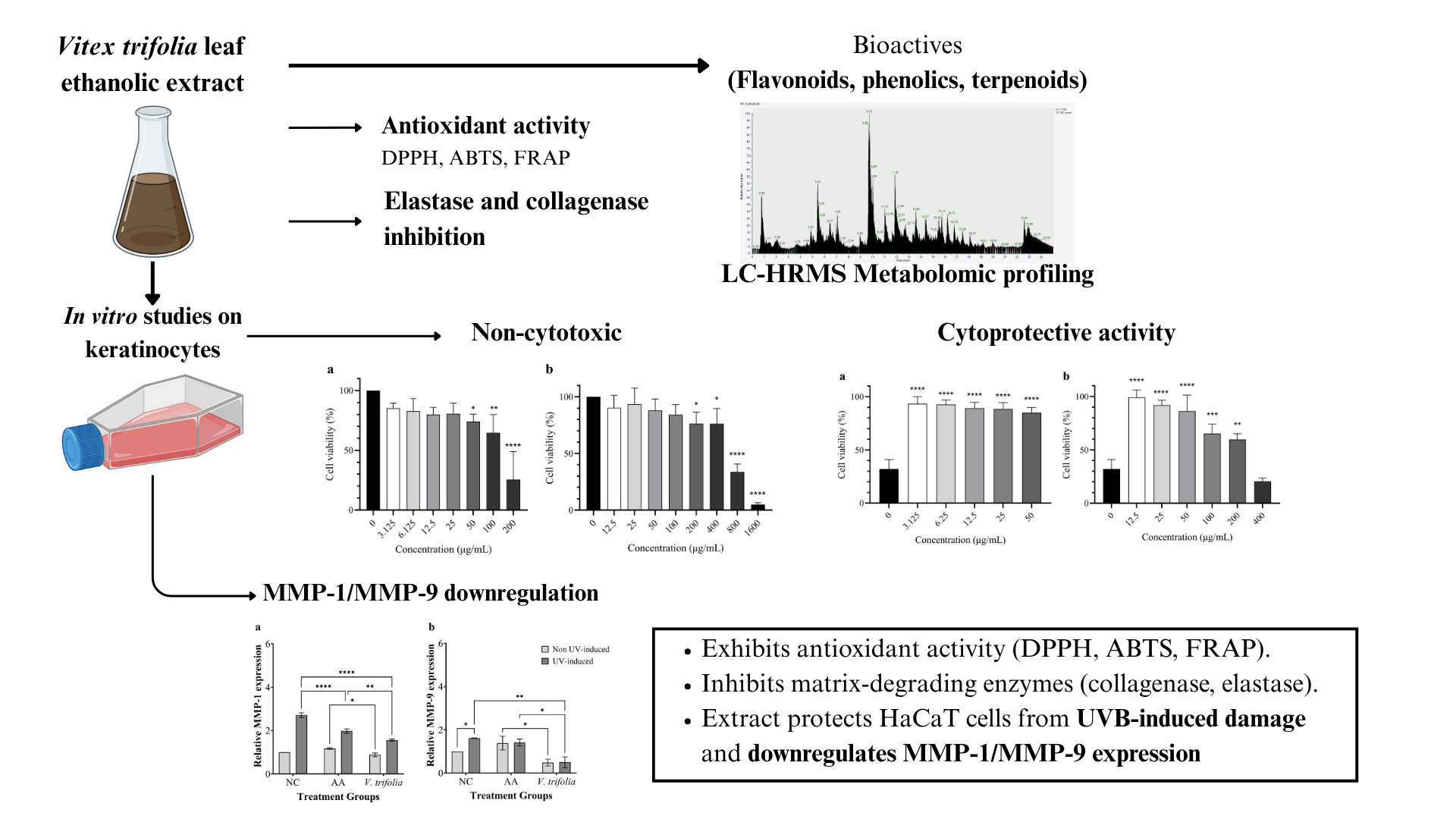

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

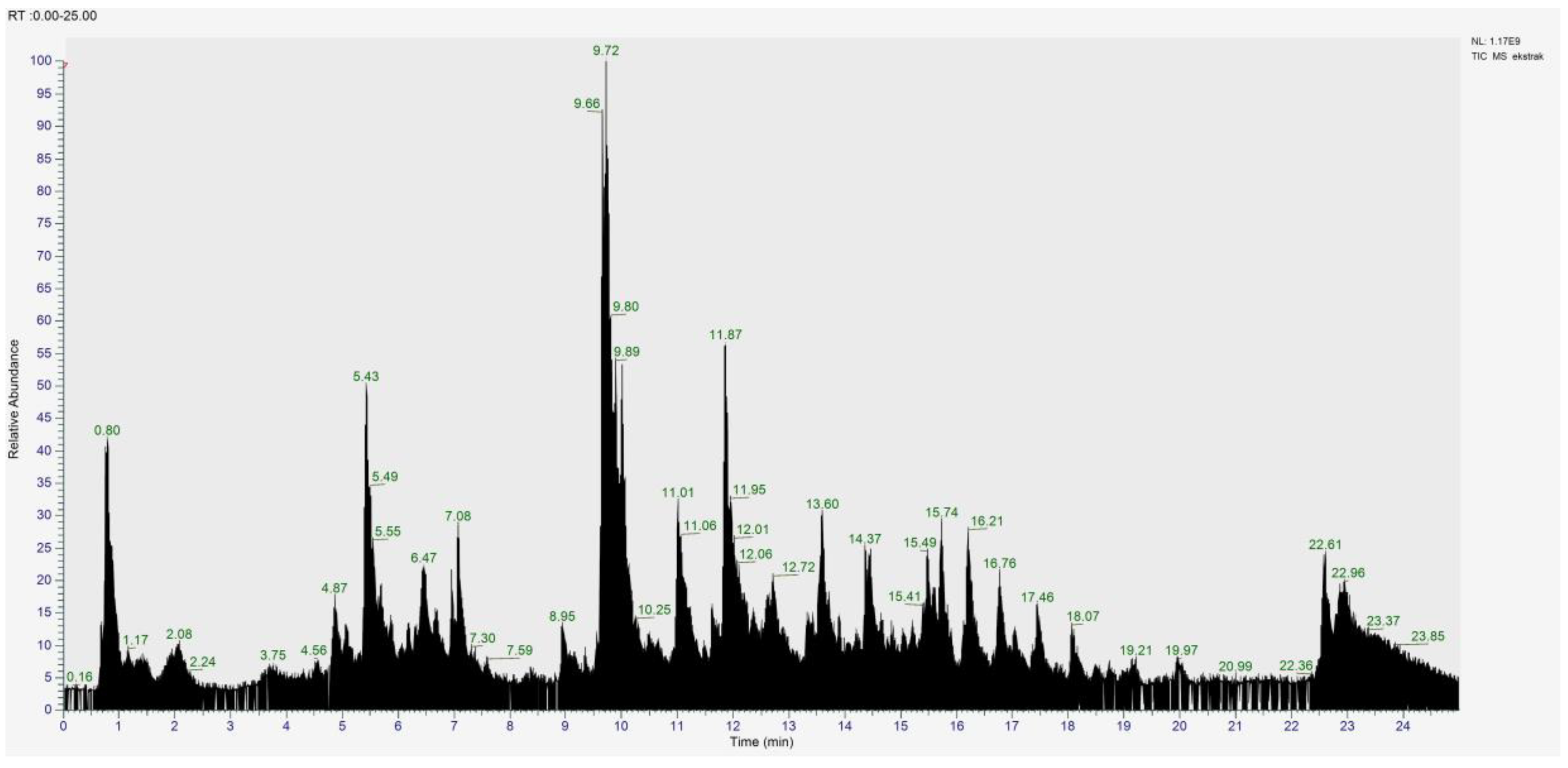

2.1. Extract Characterisation

2.2. Antioxidant and Enzymatic Bioactivities

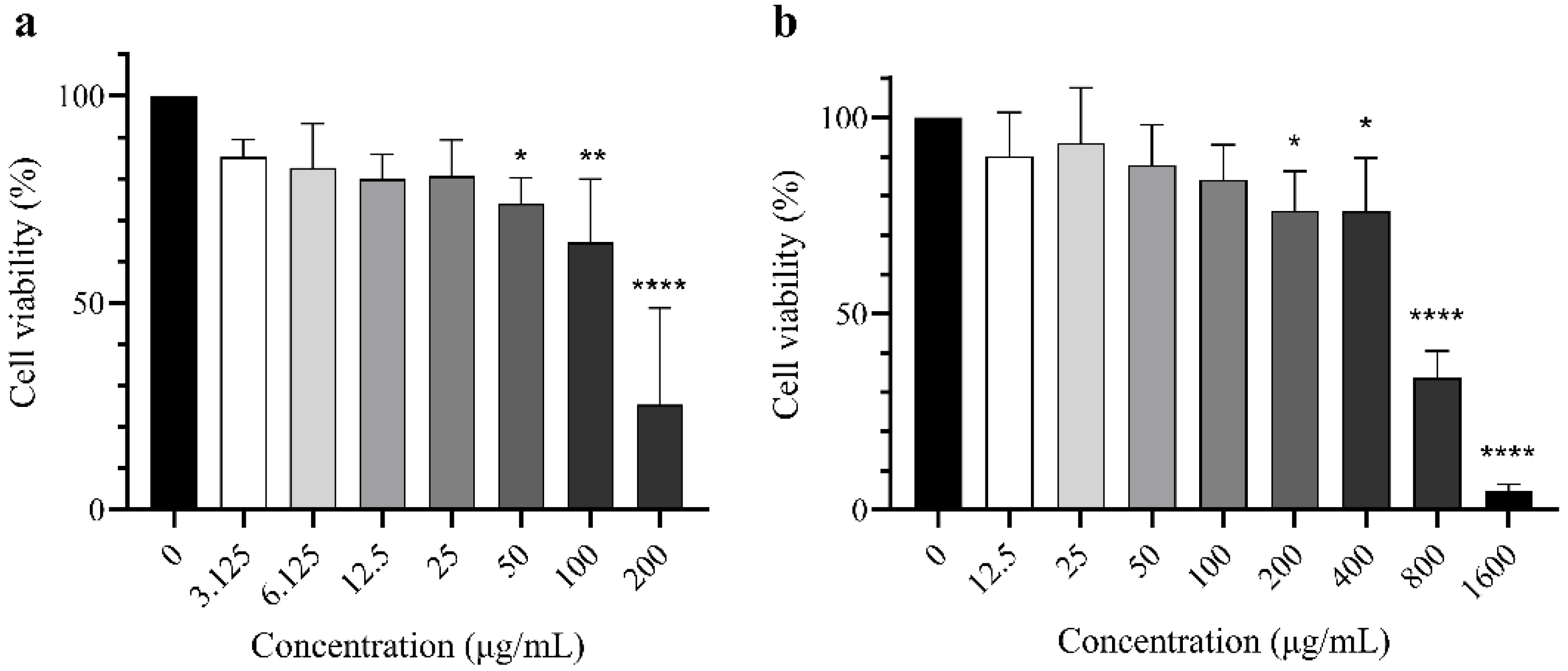

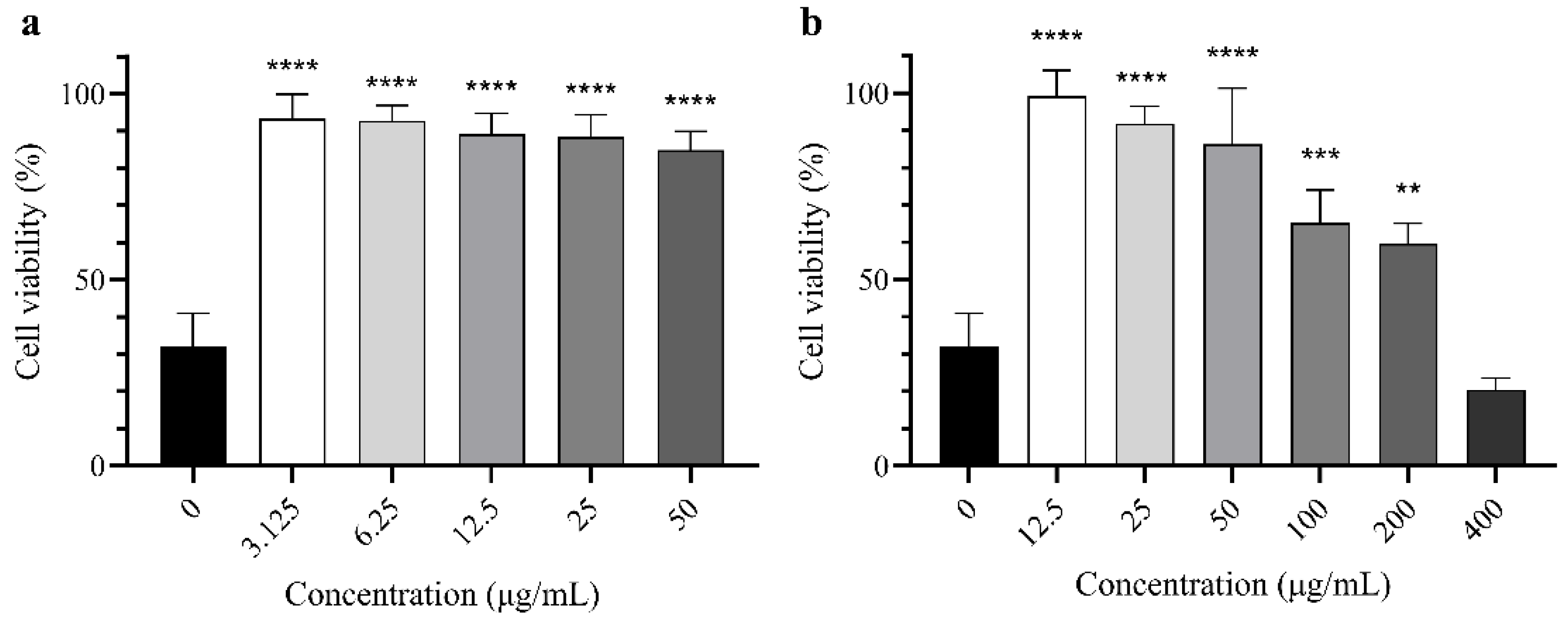

2.3. Cytoprotective Activity of Extract

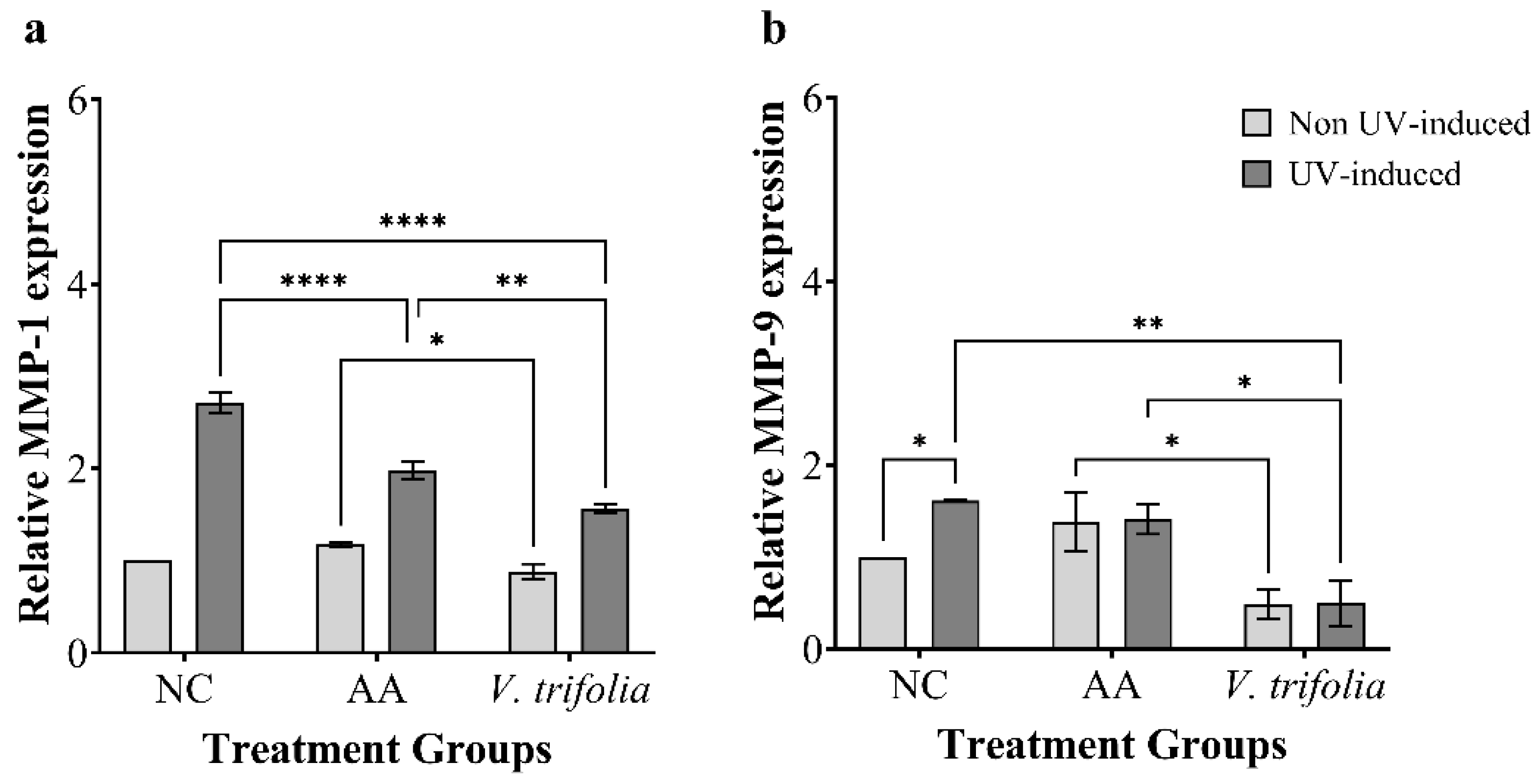

2.4. Analysis of MMP-1 and MMP-9 Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Extract Preparation

4.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

4.3. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

4.4. Metabolomic Profiling by Liquid Chromatography High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC–HRMS)

4.5. Antioxidant Assays

4.5.1. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay

4.5.2. 2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) (ABTS) Assay

4.5.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

4.6. Antielastase Assay

4.7. Anticollagenase Assay

4.8. Cell Culture

4.9. Cytotoxicity Assay

4.10. Cytoprotective Assay Against UVB-Induced Damage

4.11. Gene Expression Analysis of MMP-1 and MMP-9 Using Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.12. Data and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalent |

| HAT | Hydrogen atom transfer |

| LC–HRMS | Liquid chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry |

| MAE | Microwave-assisted extraction |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| MTS | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| QE | Quercetin equivalent |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SANA | N-succinyl-(Ala)3-p-nitroanilide |

| SET | Single electron transfer |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| UVB | Ultraviolet B |

References

- Tomas, M.; Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Kamiloglu, S.; Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E. The State of the Art in Anti-Aging: Plant-Based Phytochemicals for Skin Care. Immunity & Ageing 2025, 22, 5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Man, M.; Hu, L. Aging in the Dermis: Fibroblast Senescence and Its Significance. Aging Cell 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; He, X.; Liu, N.; Deng, H. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Ultraviolet-Induced Photodamage of the Skin. Cell Div 2024, 19, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Park, J.W.; Lee, B.-H.; Lim, K.M.; Chang, T.-S. Peroxiredoxin V Protects against UVB-Induced Damage of Keratinocytes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1435. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Photoaging: UV Radiation-Induced CGAS-STING Signaling Promotes the Aging Process in Skin by Remodeling the Immune Network. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 123. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Iwasaki, A.; Chien, A.L.; Kang, S. UVB-Mediated DNA Damage Induces Matrix Metalloproteinases to Promote Photoaging in an AhR- and SP1-Dependent Manner. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Nawaz, J.; Duan, X. Regulatory Mechanisms of Natural Active Ingredients and Compounds on Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts in Mitigating Skin Photoaging. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2024, Volume 17, 1943–1962. [CrossRef]

- Pittayapruek, P.; Meephansan, J.; Prapapan, O.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Photoaging and Photocarcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 868. [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Kang, S.-G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Boosting the Photoaged Skin: The Potential Role of Dietary Components. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1691. [CrossRef]

- Dwevedi, D.; Srivastava, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Polyphenols in Management of Skin Aging. Curr Aging Sci 2024, 17, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Mio Asni, N.S.; Rozlan, I.N.A.; Mohd Azmi, M.A.H.; Mazlan, N.W.; Mediani, A.; Baharum, S.N.; Latip, J.; Assaw, S.; Edrada-Ebel, R.A. Traditional Medicinal Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Properties, and Health Applications of Vitex Sp. Plants 2022, 11, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Mottaghipisheh, J.; Kamali, M.; Doustimotlagh, A.H.; Nowroozzadeh, M.H.; Rasekh, F.; Hashempur, M.H.; Iraji, A. A Comprehensive Review of Ethnomedicinal Approaches, Phytochemical Analysis, and Pharmacological Potential of Vitex Trifolia L. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Cavinato, M.; Waltenberger, B.; Baraldo, G.; Grade, C.V.C.; Stuppner, H.; Jansen-Dürr, P. Plant Extracts and Natural Compounds Used against UVB-Induced Photoaging. Biogerontology 2017, 18, 499–516. [CrossRef]

- Chaikhong, K.; Chumpolphant, S.; Rangsinth, P.; Sillapachaiyaporn, C.; Chuchawankul, S.; Tencomnao, T.; Prasansuklab, A. Antioxidant and Anti-Skin Aging Potential of Selected Thai Plants: In Vitro Evaluation and In Silico Target Prediction. Plants 2022, 12, 65. [CrossRef]

- Olivero-Verbel, J.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Caballero-Gallardo, K. Aromatic Plants as Cosmeceuticals: Benefits and Applications for Skin Health. Planta 2024, 260, 132. [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices — Part 5: Tests for in Vitro Cytotoxicity; Geneva, 2009;

- Ribeiro, A.; Estanqueiro, M.; Oliveira, M.; Sousa Lobo, J. Main Benefits and Applicability of Plant Extracts in Skin Care Products. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 48–65. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hyun, C.-G. Natural Products for Cosmetic Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 534. [CrossRef]

- Resende, D.I.S.P.; Jesus, A.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Sousa, E.; Cruz, M.T.; Cidade, H.; Almeida, I.F. Up-to-Date Overview of the Use of Natural Ingredients in Sunscreens. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 372. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Si, H.; Jia, Z.; Liu, D. Dietary Anti-Aging Polyphenols and Potential Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 283. [CrossRef]

- de Lima Cherubim, D.J.; Buzanello Martins, C.V.; Oliveira Fariña, L.; da Silva de Lucca, R.A. Polyphenols as Natural Antioxidants in Cosmetics Applications. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020, 19, 33–37. [CrossRef]

- Crespi, O.; Rosset, F.; Pala, V.; Sarda, C.; Accorinti, M.; Quaglino, P.; Ribero, S. Cosmeceuticals for Anti-Aging: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Regulatory Insights—A Comprehensive Review. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 209. [CrossRef]

- Wittenauer, J.; Mäckle, S.; Sußmann, D.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Carle, R. Inhibitory Effects of Polyphenols from Grape Pomace Extract on Collagenase and Elastase Activity. Fitoterapia 2015, 101, 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A. Bin; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Saklani, S.; Mishra, A.; Chandra, H.; Atanassova, M.; Stankovic, M.; Sati, B.; Shariati, M.; Nigam, M.; Khan, M.; Plygun, S.; et al. Comparative Evaluation of Polyphenol Contents and Antioxidant Activities between Ethanol Extracts of Vitex Negundo and Vitex Trifolia L. Leaves by Different Methods. Plants 2017, 6, 45. [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.W.C.; Wong, S.K.; Chan, H.T. Casticin from Vitex Species: A Short Review on Its Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. J Integr Med 2018, 16, 147–152. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cai, B.; Cui, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, B. Vitexicarpin, a Flavonoid from Vitex Trifolia L., Induces Apoptosis in K562 Cells via Mitochondria-Controlled Apoptotic Pathway. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2005, 40, 27–31.

- Jaakola, L.; Hohtola, A. Effect of Latitude on Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Plants. Plant Cell Environ 2010, 33, 1239–1247. [CrossRef]

- Gülsoy, E.; Kaya, E.D.; Türkhan, A.; Bulut, M.; Koyuncu, M.; Güler, E.; Sayın, F.; Muradoğlu, F. The Effect of Altitude on Phenolic, Antioxidant and Fatty Acid Compositions of Some Turkish Hazelnut (Coryllus Avellana L.) Cultivars. Molecules 2023, 28, 5067. [CrossRef]

- Zoratti, L.; Karppinen, K.; Luengo Escobar, A.; Häggman, H.; Jaakola, L. Light-Controlled Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Fruits. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, P.; Thangam, E.B. Vitex Trifolia L. Modulates Inflammatory Mediators via down-Regulation of the NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway in Carrageenan-Induced Acute Inflammation in Experimental Rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2022, 298, 115583. [CrossRef]

- Thring, T.S.; Hili, P.; Naughton, D.P. Anti-Collagenase, Anti-Elastase and Anti-Oxidant Activities of Extracts from 21 Plants. BMC Complement Altern Med 2009, 9, 27. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rangel, J.C.; Benavides, J.; Heredia, J.B.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. The Folin–Ciocalteu Assay Revisited: Improvement of Its Specificity for Total Phenolic Content Determination. Analytical Methods 2013, 5, 5990. [CrossRef]

- Masyita, A.; Mustika Sari, R.; Dwi Astuti, A.; Yasir, B.; Rahma Rumata, N.; Emran, T. Bin; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and Terpenoids as Main Bioactive Compounds of Essential Oils, Their Roles in Human Health and Potential Application as Natural Food Preservatives. Food Chem X 2022, 13, 100217. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Lupeol, a Novel Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Cancer Dietary Triterpene. Cancer Lett 2009, 285, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, A.T.; Jahidin, A.H.; Zakaria, Y.; Hazizul Hasan, M. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Vitex Trifolia Leaves Hydroalcoholic Extract against Hydrogen Peroxide(H2O2)- and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Raw 264.7 Cells. Malaysian Applied Biology 2022, 51, 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Francenia Santos-Sánchez, N.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Antioxidant Compounds and Their Antioxidant Mechanism. In Antioxidants; IntechOpen, 2019.

- Wei, M.; He, X.; Liu, N.; Deng, H. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Ultraviolet-Induced Photodamage of the Skin. Cell Div 2024, 19, 1. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Samarasinghe, A. How to Assess Antioxidant Activity? Advances, Limitations, and Applications of in Vitro, in Vivo, and Ex Vivo Approaches. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2025, 7, 50. [CrossRef]

- Yusharyahya, S.N. Mekanisme Penuaan Kulit Sebagai Dasar Pencegahan Dan Pengobatan Kulit Menua. eJournal Kedokteran Indonesia 2021, 9, 150. [CrossRef]

- Pientaweeratch, S.; Panapisal, V.; Tansirikongkol, A. Antioxidant, Anti-Collagenase and Anti-Elastase Activities of Phyllanthus Emblica , Manilkara Zapota and Silymarin: An in Vitro Comparative Study for Anti-Aging Applications. Pharm Biol 2016, 54, 1865–1872. [CrossRef]

- Sin, B.Y.; Kim, H.P. Inhibition of Collagenase by Naturally-Occurring Flavonoids. Arch Pharm Res 2005, 28, 1152–1155. [CrossRef]

- Masaki, H. Role of Antioxidants in the Skin: Anti-Aging Effects. J Dermatol Sci 2010, 58, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.; Thomas, J.; Amaresan, N. Cytotoxicity Assay. In; 2023; pp. 191–193.

- McCarty, M.F.; Contreras, F. Increasing Superoxide Production and the Labile Iron Pool in Tumor Cells May Sensitize Them to Extracellular Ascorbate. Front Oncol 2014, 4. [CrossRef]

- Klingelhoeffer, C.; Kämmerer, U.; Koospal, M.; Mühling, B.; Schneider, M.; Kapp, M.; Kübler, A.; Germer, C.-T.; Otto, C. Natural Resistance to Ascorbic Acid Induced Oxidative Stress Is Mainly Mediated by Catalase Activity in Human Cancer Cells and Catalase-Silencing Sensitizes to Oxidative Stress. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12, 61. [CrossRef]

- Sestili, P.; Brandi, G.; Brambilla, L.; Cattabeni, F.; Cantoni, O. Hydrogen Peroxide Mediates the Killing of U937 Tumor Cells Elicited by Pharmacologically Attainable Concentrations of Ascorbic Acid: Cell Death Prevention by Extracellular Catalase or Catalase from Cocultured Erythrocytes or Fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996, 277, 1719–1725.

- Garbi, M.I.; Osman, E.E.; Kabbashi, A.S.; Saleh, M.S.; Yousof, Y.S.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Salam, H.A. Cytotoxicity of Vitex Trifolia Leaf Extracts On Mcf-7 and Vero Cell Lines. International Research Journal of Natural Sciences 2017, 4, 89–93.

- Wee, H.-N.; Neo, S.-Y.; Singh, D.; Yew, H.-C.; Qiu, Z.-Y.; Tsai, X.-R.C.; How, S.-Y.; Yip, K.-Y.C.; Tan, C.-H.; Koh, H.-L. Effects of Vitex Trifolia L. Leaf Extracts and Phytoconstituents on Cytokine Production in Human U937 Macrophages. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20, 91. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, J. Cytoprotective Effects and Antioxidant Activities of Acteoside and Various Extracts of Clerodendrum Cyrtophyllum Turcz Leaves against T-BHP Induced Oxidative Damage. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 12630. [CrossRef]

- Marais, T.L. Des; Kluz, T.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Gesumaria, L.; Matsui, M.S.; Costa, M.; Sun, H. Transcription Factors and Stress Response Gene Alterations in Human Keratinocytes Following Solar Simulated Ultra Violet Radiation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13622. [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Liu, R.; Jing, R.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Fu, M.; Ye, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, W.; et al. Cryptotanshinone Protects Skin Cells from Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Photoaging via Its Antioxidant Effect and by Reducing Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Inhibiting Apoptosis. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Guo, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jing, R.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, N.; Li, X. Keratinocyte Growth Factor 2 Ameliorates UVB-Induced Skin Damage via Activating the AhR/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Savini, I.; D’Angelo, I.; Ranalli, M.; Melino, G.; Avigliano, L. Ascorbic Acid Maintenance in HaCaT Revents Radical Formation and Apoptosis by UV-B. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1172–1180. [CrossRef]

- Erika Chriscensia; Joshua Nathanael; Urip Perwitasari; Agus Budiawan Naro Putra; Shakila Angjaya Adiyanto; Pietradewi Hartrianti Potential Utilisation of Theobroma Cacao Pod Husk Extract: Protective Capability Evaluation Against Pollution Models and Formulation into Niosomes. Trop Life Sci Res 2024, 35, 107–140. [CrossRef]

- Widiatmoko, A.; Fitri, L.E.; Endharti, A.T.; Murlistyarini, S.; Brahmanti, H.; Yuniaswan, A.P.; Ekasari, D.P.; Rasyidi, F.; Nahlia, N.L.; Safitri, P.R. Inhibition Effect of Physalis Angulata Leaf Extract on Viability, Collagen Type I, and Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) but Not Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) of Keloid Fibroblast Culture. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2023, Volume 16, 2365–2373. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.J.; Navarro, C.; Durán, P.; Galan-Freyle, N.J.; Parra Hernández, L.A.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C.; Castelanich, D.; Bermúdez, V.; Chacin, M. Antioxidants in Photoaging: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2403. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.-R.; Alam, M.B.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, S.-H. Attenuation of UVB-Induced Photo-Aging by Polyphenolic-Rich Spatholobus Suberectus Stem Extract Via Modulation of MAPK/AP-1/MMPs Signaling in Human Keratinocytes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1341. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M. Luteolin Prevents UVB-Induced Skin Photoaging Damage by Modulating SIRT3/ROS/MAPK Signaling: An in Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Perlak, M.; Olszowy, M.; Woźniak, M. The Natural Defense: Anti-Aging Potential of Plant-Derived Substances and Technological Solutions Against Photoaging. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 8061. [CrossRef]

- Mir, H.A.; Ali, R.; Wani, Z.A.; Khanday, F.A. Pro-Oxidant Vitamin C Mechanistically Exploits P66Shc/Rac1 GTPase Pathway in Inducing Cytotoxicity. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 205, 154–168. [CrossRef]

| Total flavonoid content (mg QE/g extract) |

Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g extract) |

Yield (%) |

| 1.99 ± 0.02 | 78.52 ± 0.01 | 31.8 |

| No | Compound | Molecular formula | Molecular weight (m/z) | Class | AUC (×106) |

| 1 | Casticin (NP-001928) | C19H18O8 | 374.099 | Flavonoid | 2384.32 |

| 2 | (1ξ)-1,5-Anhydro-1-[2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-4H-chromen-8-yl]-D-galactitol | C21H20O11 | 448.100 | Flavonoid | 773.48 |

| 3 | (2S,3S,4S,5R,6S)-6-{[5,7-dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-oxo-4H-chromen-3-yl]oxy}-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid | C21H18O12 | 462.079 | Phenolic acid | 522.29 |

| 4 | 5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-3,6-dimethoxy-4H-chromen-4-one | C18H16O8 | 360.083 | Flavonoid | 455.82 |

| 5 | 4-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.047 | Phenolic acid | 339.04 |

| 6 | (1R,3R,4R,4aS)-4-Hydroxy-3,4a,8,8-tetramethyl-4-[2-(5-oxo-2,5-dihydro-3-furanyl)ethyl]decahydro-1-naphthalenyl acetate | C22H34O5 | 378.239 | Diterpenoid | 285.99 |

| 7 | (1r,3R,4s,5S)-4-{[(2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoyl]oxy}-1,3,5-trihydroxycyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid | C16H18O9 | 354.094 | Phenolic acid | 279.47 |

| 8 | (1S,3R,4S,5R)-3,5-bis({[(2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoyl]oxy})-1,4-dihydroxycyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid | C25H24O12 | 516.126 | Phenolic acid | 273.62 |

| 9 | Lupeol | C30H50O | 426.385 | Triterpenoid | 229.73 |

| 10 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 138.032 | Phenolic acid | 161.62 |

| Sample |

IC50 – DPPH (μg/mL) |

IC50 – ABTS (μg/mL) |

FRAP assay (FeSO4 E/100 g extract) |

| Ascorbic acid | 5.39 ± 0.11 | 4.34 ± 0.08 | 316.04 ± 5.86 |

| V. trifolia leaves extract | 63.47 ± 0.24 | 70.13 ± 1.28 | 36.33 ± 0.18 |

| Sample | IC50 – Antielastase (μg/mL) | IC50 – Anticollagenase (μg/mL) |

| Quercetin | 5.50 ± 0.05 | N/A |

| 1,10-phenanthroline | N/A | 3.27 ± 0.15 |

| V. trifolia leaves extract | 400 ± 0.01 | 27.94 ± 3.20 |

| Step | Cycle | Temperature (°C) | Duration |

| Initial denaturation | 1 | 95 | 2 min |

| Denaturation | 40 | 95 | 5 s |

| Annealing | 65 | 10 s | |

| Extension | 72 | 20 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).