Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

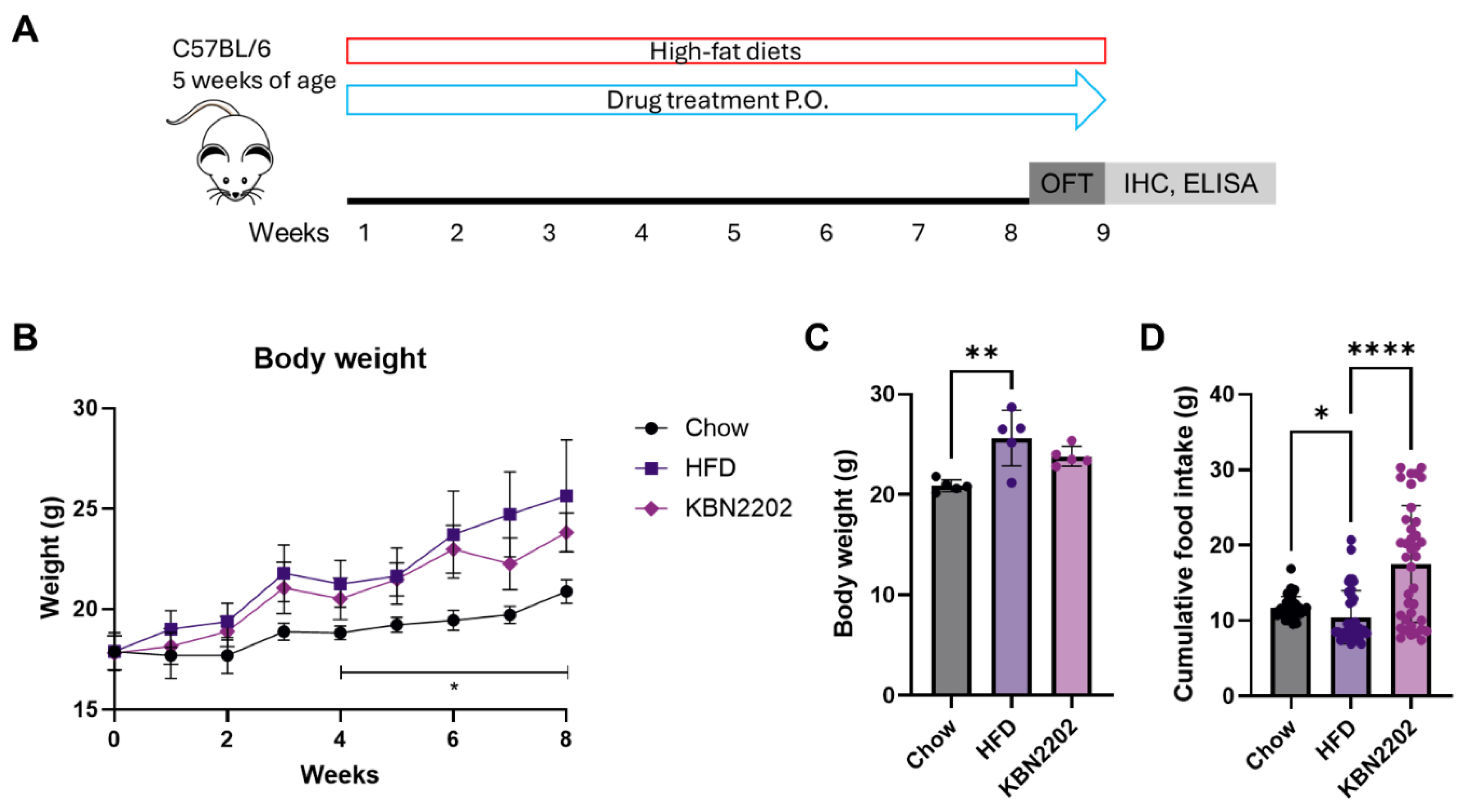

2.1. Effects of KBN2202 on Body Weight and Dietary Intake

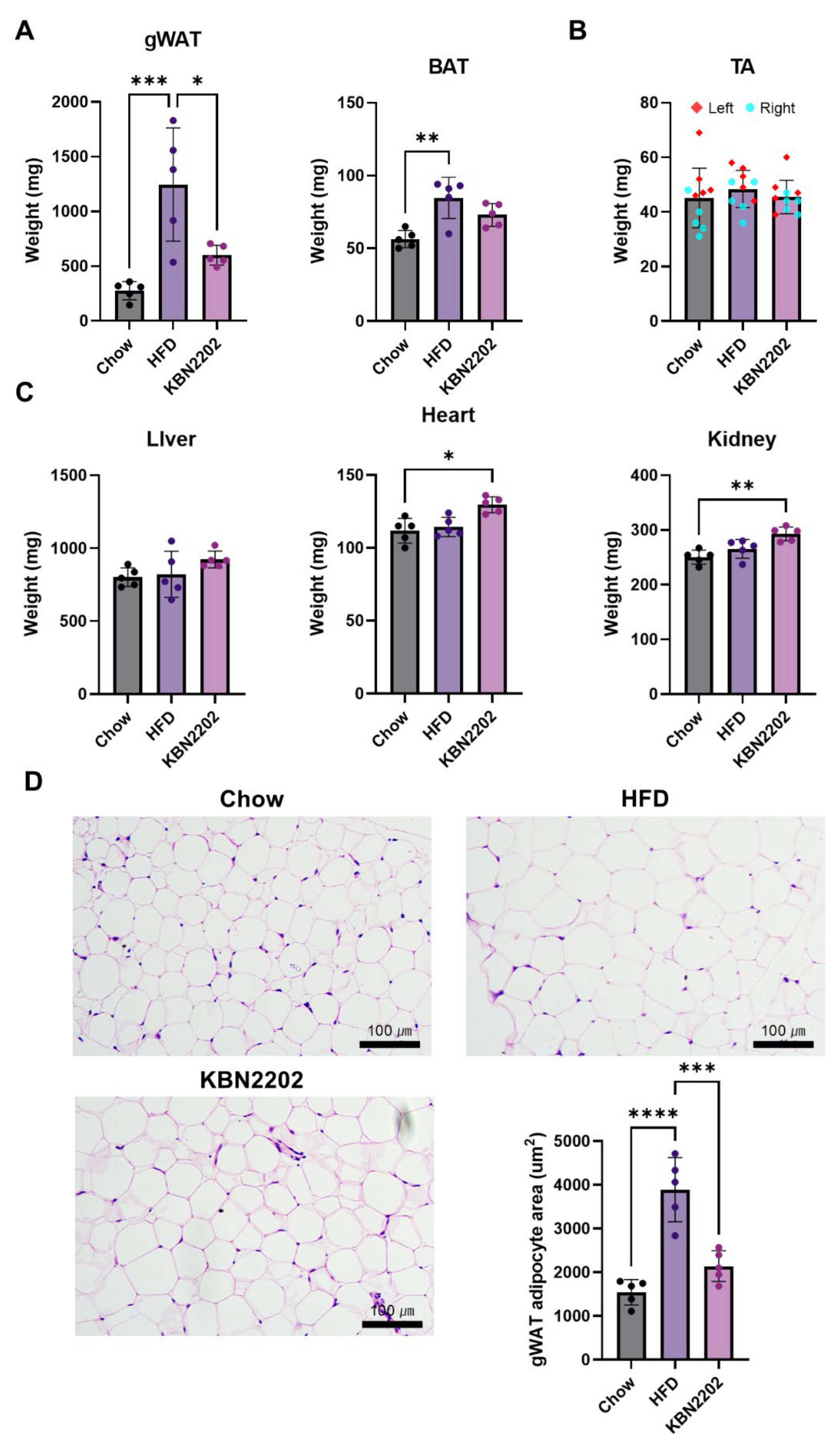

2.2. Suppression of gWAT Expansion and Adipocyte Hypertrophy by KBN2202

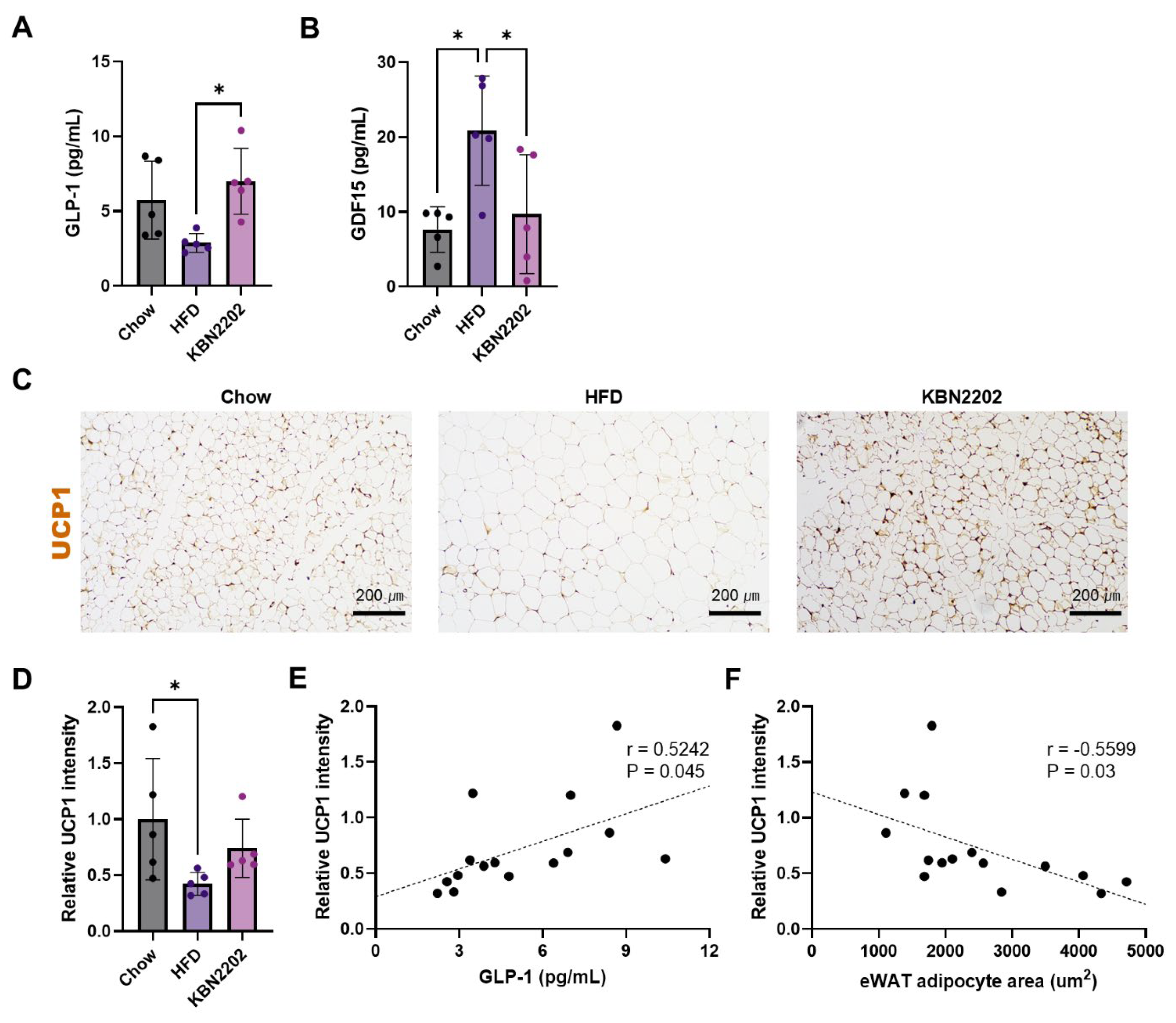

2.3. Modulation of Thermogenic Markers and GLP-1 Levels by KBN2202

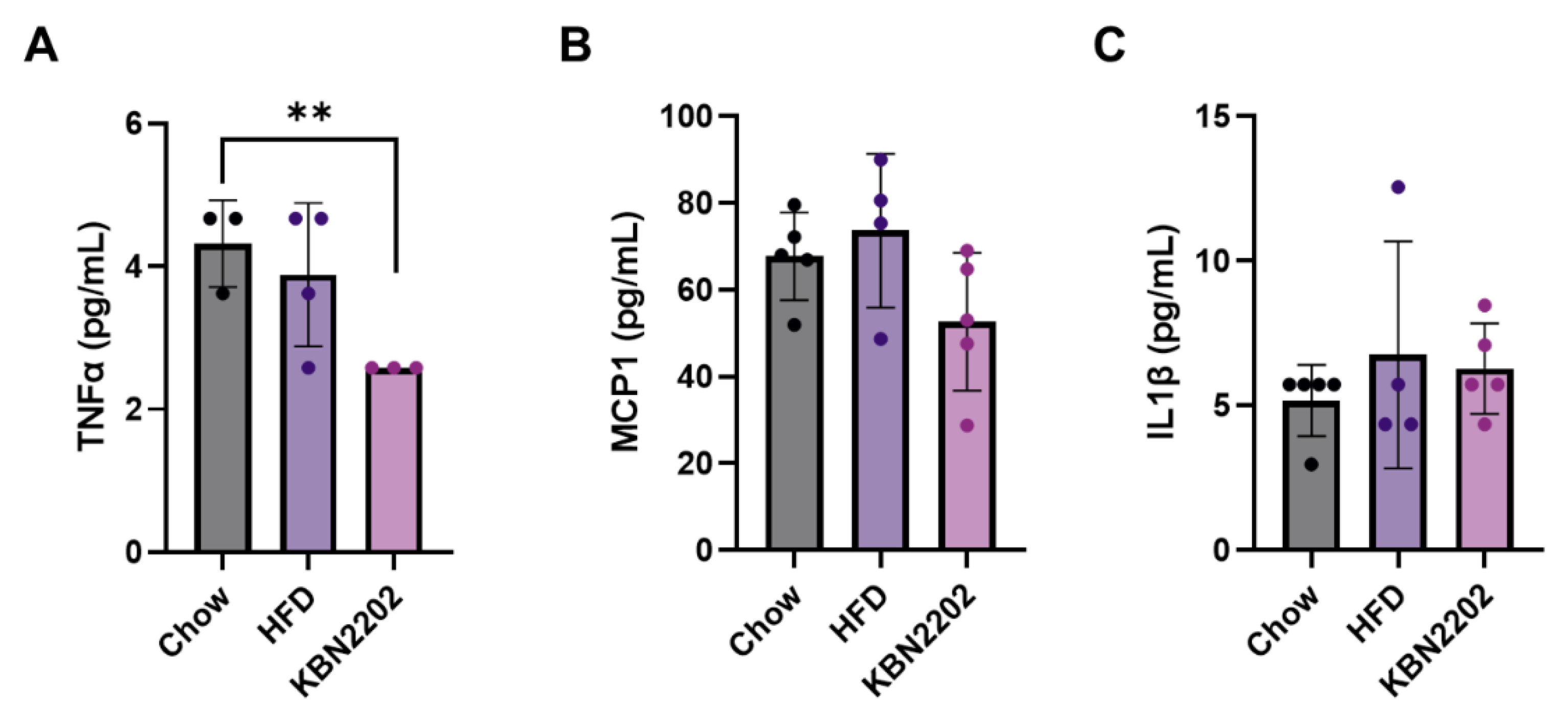

2.4. Effects of KBN2202 on Systemic Inflammation in HFD-Fed Mice

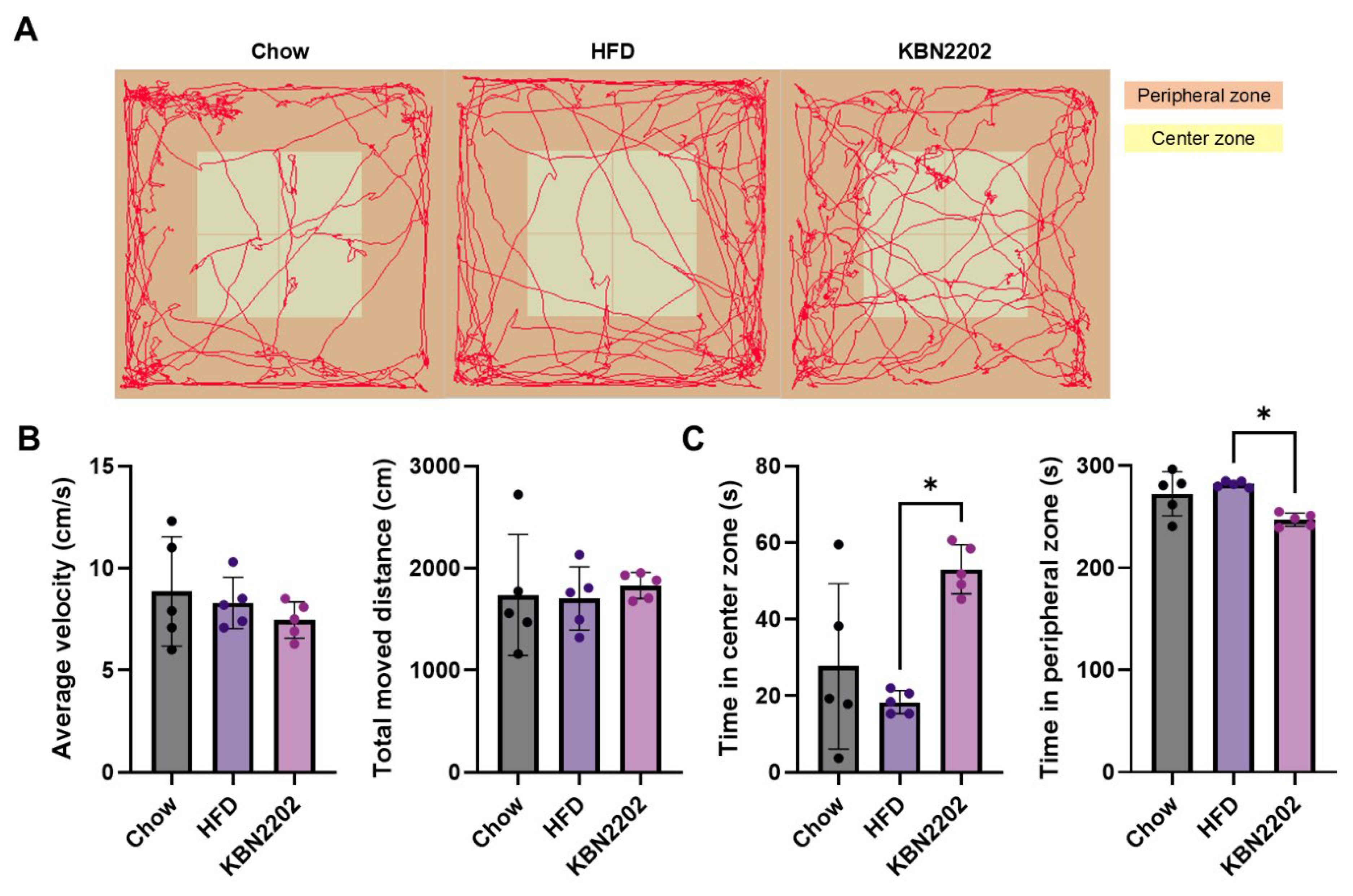

2.5. Effects of KBN2202 on Locomotor Activity and Anxiety-Like Behavior in the Open Field Test

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Model of High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity

4.2. Drug Treatment

4.3. Physiological Measurements and Tissue Collection

4.4. Quantification of Serum Cytokines by ELISA and Multiplex Analysis

4.5. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

4.6. Open Field Test (OFT)

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| gWAT | Gonadal white adipose tissue |

| GDF15 | Growth differentiation factor 15 |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1RA | GLP-1 receptor agonist |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| LOB | Limit of blank |

| MFI | Median fluorescence intensity |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| OFT | Open field test |

| TA | Tibialis anterior |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

References

- Lin X, Li H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:706978. [CrossRef]

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–45. [CrossRef]

- Bensussen A, Torres-Magallanes JA, Roces de Alvarez-Buylla E. Molecular tracking of insulin resistance and inflammation development on visceral adipose tissue. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1014778. [CrossRef]

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH, World Obesity F. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–23. [CrossRef]

- Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. [CrossRef]

- Bluher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):288–98. [CrossRef]

- Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(1):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1785–8. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–7. [CrossRef]

- Muller TD, Bluher M, Tschop MH, DiMarchi RD. Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(3):201–23. [CrossRef]

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989–1002. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson L, Holst-Hansen T, Laursen PN, Rinnov AR, Batterham RL, Garvey WT. Effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly on 10-year type 2 diabetes risk in adults with overweight or obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(9):2249–59. [CrossRef]

- Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, Davies M, Frias JP, Koroleva A, et al. Effect of Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo as an Adjunct to Intensive Behavioral Therapy on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1403–13. [CrossRef]

- Jensen SBK, Blond MB, Sandsdal RM, Olsen LM, Juhl CR, Lundgren JR, et al. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or both combined followed by one year without treatment: a post-treatment analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;69:102475. [CrossRef]

- Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, Hesse D, Greenway FL, Jensen C, et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1414–25. [CrossRef]

- Klimova J, Mraz M, Kratochvilova H, Lacinova Z, Novak K, Michalsky D, et al. Gene Profile of Adipose Tissue of Patients with Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma. Biomedicines. 2022;10(3). [CrossRef]

- Vane JR, Botting RM. Mechanism of action of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1998;104(3A):2S–8S; discussion 21S–22S. [CrossRef]

- Yin MJ, Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of I(kappa)B kinase-beta. Nature. 1998;396(6706):77–80. [CrossRef]

- Kopp E, Ghosh S. Inhibition of NF-kappa B by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science. 1994;265(5174):956–9. [CrossRef]

- Hardie DG. AMPK: a key regulator of energy balance in the single cell and the whole organism. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32 Suppl 4:S7–12. [CrossRef]

- Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker KJ, et al. The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science. 2012;336(6083):918–22. [CrossRef]

- Kim JK, Kim YJ, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Moore I, Lee J, et al. Prevention of fat-induced insulin resistance by salicylate. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(3):437–46. [CrossRef]

- Choi HE, Jeon EJ, Kim DY, Choi MJ, Yu H, Kim JI, et al. Sodium salicylate induces browning of white adipocytes via M2 macrophage polarization by HO-1 upregulation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;928:175085. [CrossRef]

- Smith BK, Ford RJ, Desjardins EM, Green AE, Hughes MC, Houde VP, et al. Salsalate (Salicylate) Uncouples Mitochondria, Improves Glucose Homeostasis, and Reduces Liver Lipids Independent of AMPK-beta1. Diabetes. 2016;65(11):3352–61. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann NC, Davies MJ, Lingvay I, Knop FK. Semaglutide for the treatment of overweight and obesity: A review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25(1):18–35. [CrossRef]

- Melson E, Ashraf U, Papamargaritis D, Davies MJ. What is the pipeline for future medications for obesity? Int J Obes (Lond). 2025;49(3):433–51. [CrossRef]

- Nunn E, Jaiswal N, Gavin M, Uehara K, Stefkovich M, Drareni K, et al. Antibody blockade of activin type II receptors preserves skeletal muscle mass and enhances fat loss during GLP-1 receptor agonism. Mol Metab. 2024;80:101880. [CrossRef]

- Deschamps D, Fisch C, Fromenty B, Berson A, Degott C, Pessayre D. Inhibition by salicylic acid of the activation and thus oxidation of long chain fatty acids. Possible role in the development of Reye's syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259(2):894–904.

- Stubbins RE, Najjar K, Holcomb VB, Hong J, Nunez NP. Oestrogen alters adipocyte biology and protects female mice from adipocyte inflammation and insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(1):58–66. [CrossRef]

- Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(23):12729–34. [CrossRef]

- Lopez M, Tena-Sempere M. Estradiol effects on hypothalamic AMPK and BAT thermogenesis: A gateway for obesity treatment? Pharmacol Ther. 2017;178:109–22. [CrossRef]

- Winzell MS, Ahren B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: a model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 3:S215–9. [CrossRef]

- Choi MS, Kim YJ, Kwon EY, Ryoo JY, Kim SR, Jung UJ. High-fat diet decreases energy expenditure and expression of genes controlling lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function and skeletal system development in the adipose tissue, along with increased expression of extracellular matrix remodelling- and inflammation-related genes. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(6):867–77. [CrossRef]

- An SM, Cho SH, Yoon JC. Adipose Tissue and Metabolic Health. Diabetes Metab J. 2023;47(5):595–611. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda K, Yamada T. UCP1 Dependent and Independent Thermogenesis in Brown and Beige Adipocytes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:498. [CrossRef]

- Kajimura S, Spiegelman BM, Seale P. Brown and Beige Fat: Physiological Roles beyond Heat Generation. Cell Metab. 2015;22(4):546–59. [CrossRef]

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in the brain: controlling food intake and body weight. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4223–6. [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell. 2012;151(2):400–13. [CrossRef]

- Martins FF, Marinho TS, Cardoso LEM, Barbosa-da-Silva S, Souza-Mello V, Aguila MB, et al. Semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonist) stimulates browning on subcutaneous fat adipocytes and mitigates inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in visceral fat adipocytes of obese mice. Cell Biochem Funct. 2022;40(8):903–13. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hu X, Xie Z, Li J, Huang C, Huang Y. Overview of growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) in metabolic diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;176:116809. [CrossRef]

- Chang JY, Hong HJ, Kang SG, Kim JT, Zhang BY, Shong M. The Role of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 in Energy Metabolism. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(3):363–71. [CrossRef]

- Hale C, Veniant MM. Growth differentiation factor 15 as a potential therapeutic for treating obesity. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101117. [CrossRef]

- Benichou O, Coskun T, Gonciarz MD, Garhyan P, Adams AC, Du Y, et al. Discovery, development, and clinical proof of mechanism of LY3463251, a long-acting GDF15 receptor agonist. Cell Metab. 2023;35(2):274–86 e10. [CrossRef]

- Patel S, Alvarez-Guaita A, Melvin A, Rimmington D, Dattilo A, Miedzybrodzka EL, et al. GDF15 Provides an Endocrine Signal of Nutritional Stress in Mice and Humans. Cell Metab. 2019;29(3):707–18 e8. [CrossRef]

- L'Homme L, Sermikli BP, Haas JT, Fleury S, Quemener S, Guinot V, et al. Adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and hepatocyte stress increase GDF-15 throughout development of obesity to MASH. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7173. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Autieri MV, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;320(3):C375–C91. [CrossRef]

- Kunz HE, Hart CR, Gries KJ, Parvizi M, Laurenti M, Dalla Man C, et al. Adipose tissue macrophage populations and inflammation are associated with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;321(1):E105–E21. [CrossRef]

- Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1494–505. [CrossRef]

- Rubin DA, Hackney AC. Inflammatory cytokines and metabolic risk factors during growth and maturation: influence of physical activity. Med Sport Sci. 2010;55:43–55. [CrossRef]

- Austin RL, Rune A, Bouzakri K, Zierath JR, Krook A. siRNA-mediated reduction of inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB kinase prevents tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2008;57(8):2066–73. [CrossRef]

- Suganami T, Ogawa Y. Adipose tissue macrophages: their role in adipose tissue remodeling. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(1):33–9. [CrossRef]

- Ip CK, Zhang L, Farzi A, Qi Y, Clarke I, Reed F, et al. Amygdala NPY Circuits Promote the Development of Accelerated Obesity under Chronic Stress Conditions. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):111–28 e6. [CrossRef]

- Lee S-Y, Kim JC, Choi MR, Song J, Kim M, Chang S-H, Kim JS, Park J-S and Lee S-R. KBN2202, a Salicylic Acid Derivative, Preserves Neuronal Architecture, Enhances Neurogenesis, Attenuates Amyloid and Inflammatory Pathology, and Restores Recognition Memory in 5xFAD Mice at an Advanced Stage of AD Pathophysiology. Int.J. Mol. Sci. 2025.;26(22). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).