Submitted:

01 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Results from Human Study

2.1.1. Baseline Characteristics

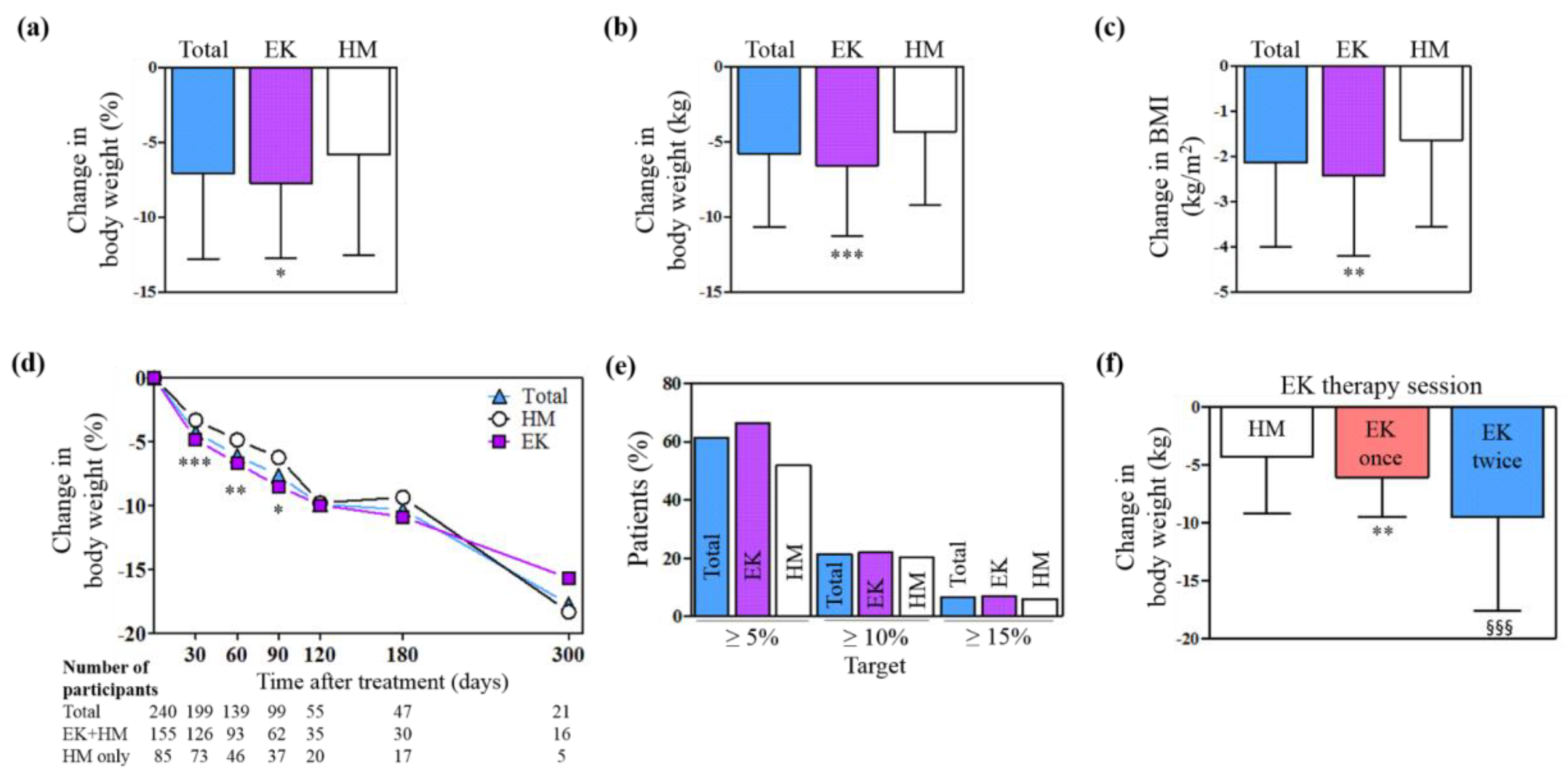

2.1.2. Effects on Body Weight

2.1.3. Change in the Body Compositions

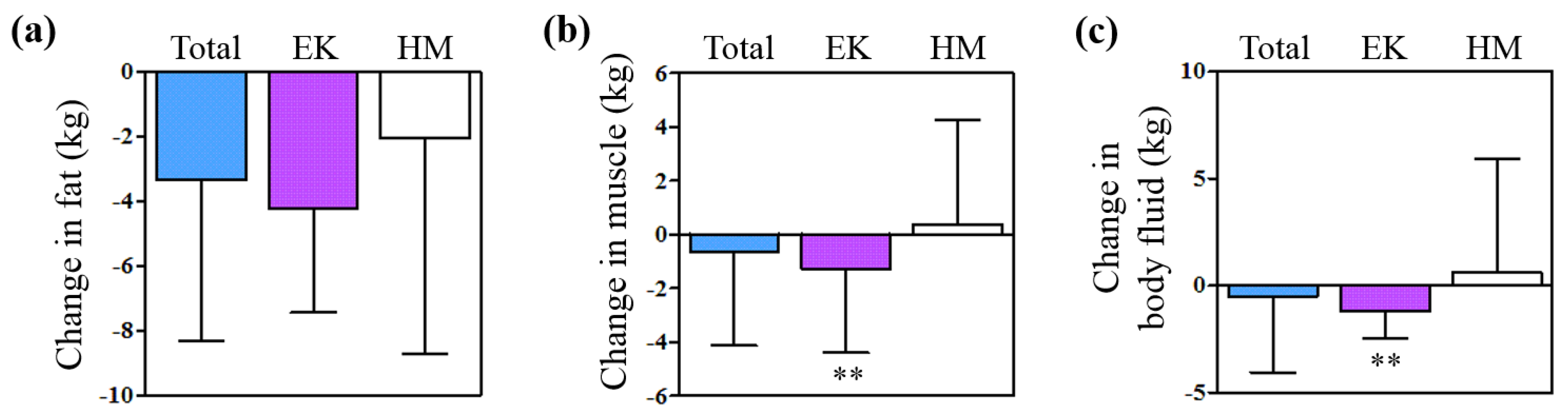

2.1.4. Adverse Events after EK Therapy and during HM Treatment

2.2. Results from Animal Model

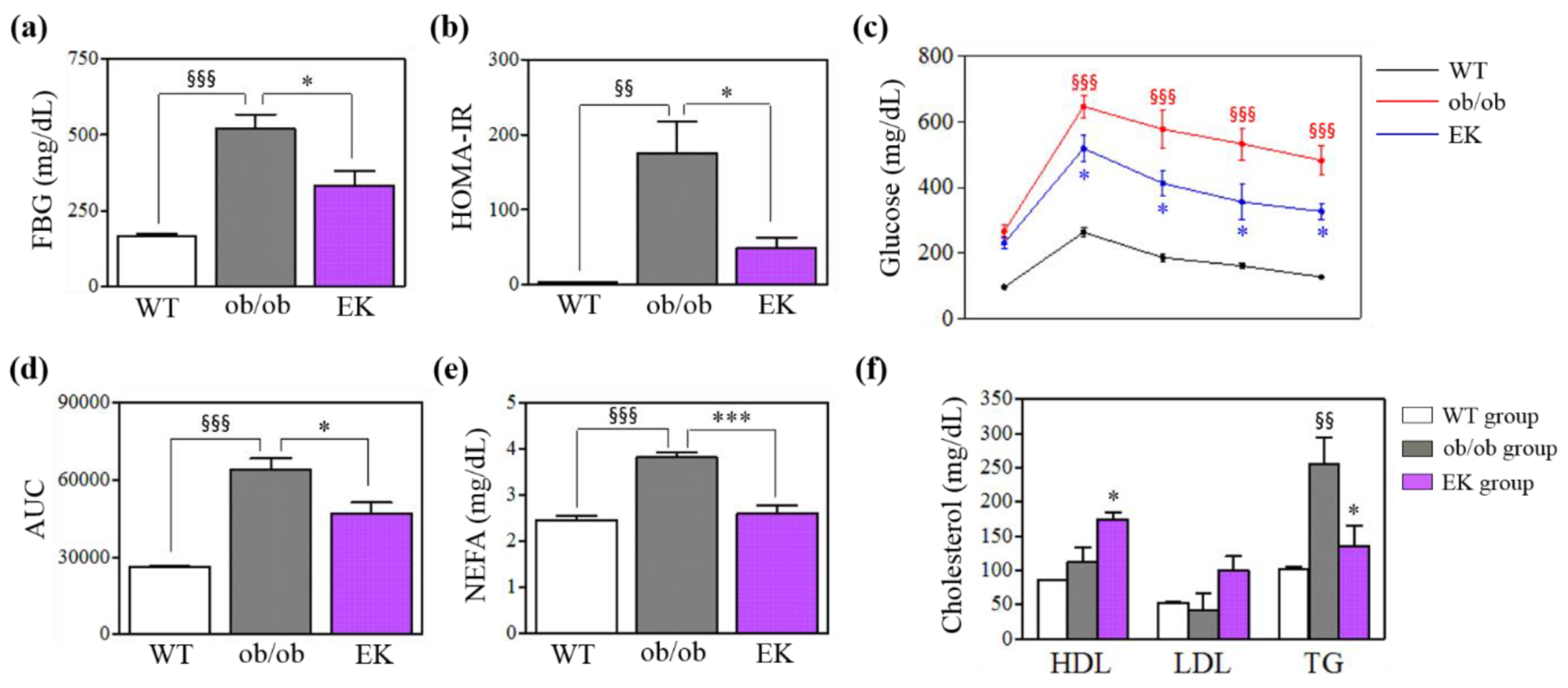

2.2.1. Body Weight, Glucose Metabolism and Lipid Profile

2.2.2. Safety Profile

2.2.3. Mechanism of EK Therapy in Macrophages and Monocytes

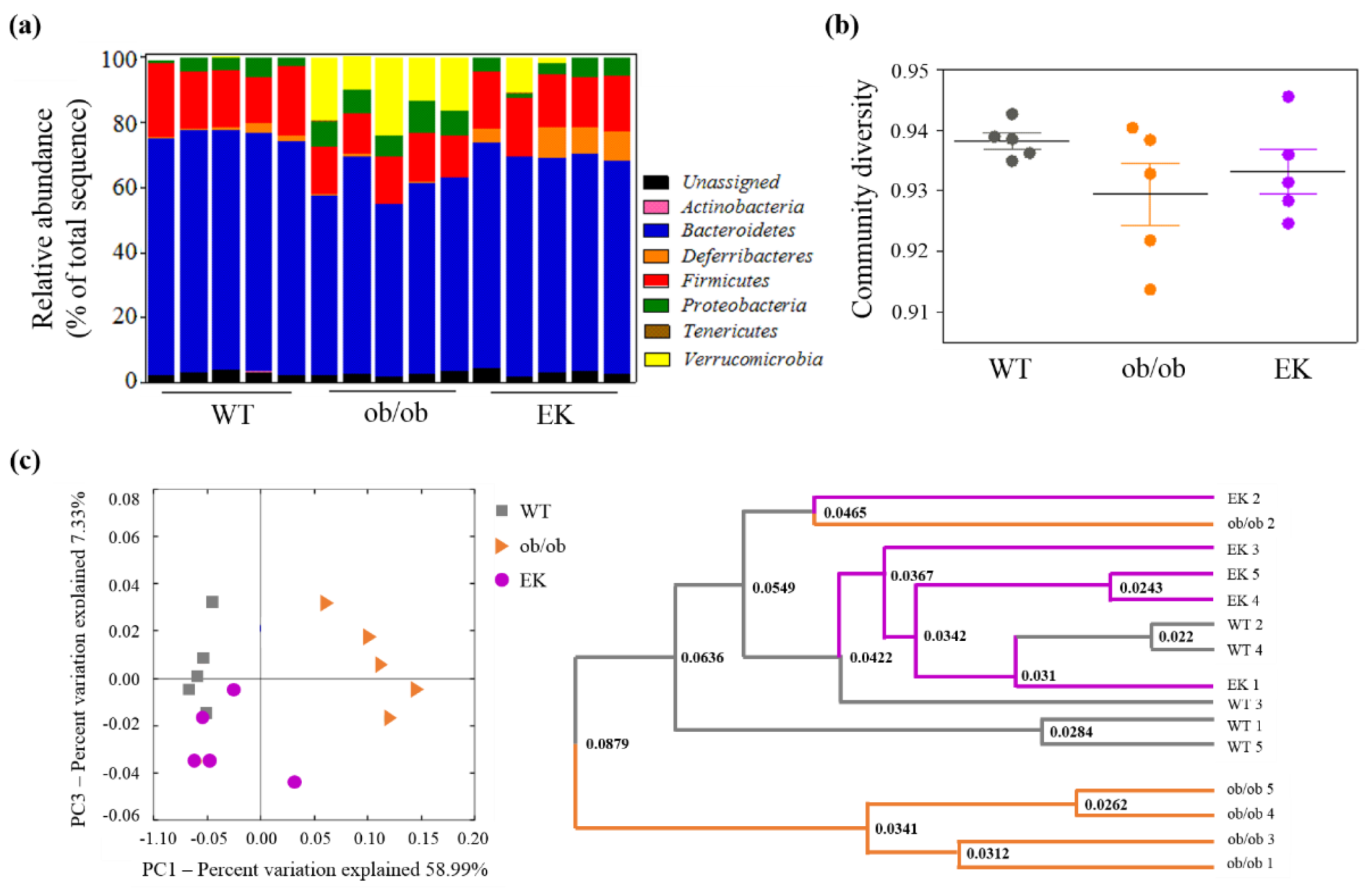

2.2.4. Mechanism of EK Therapy in Gut Microbiota

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. A Real-World Clinical Study

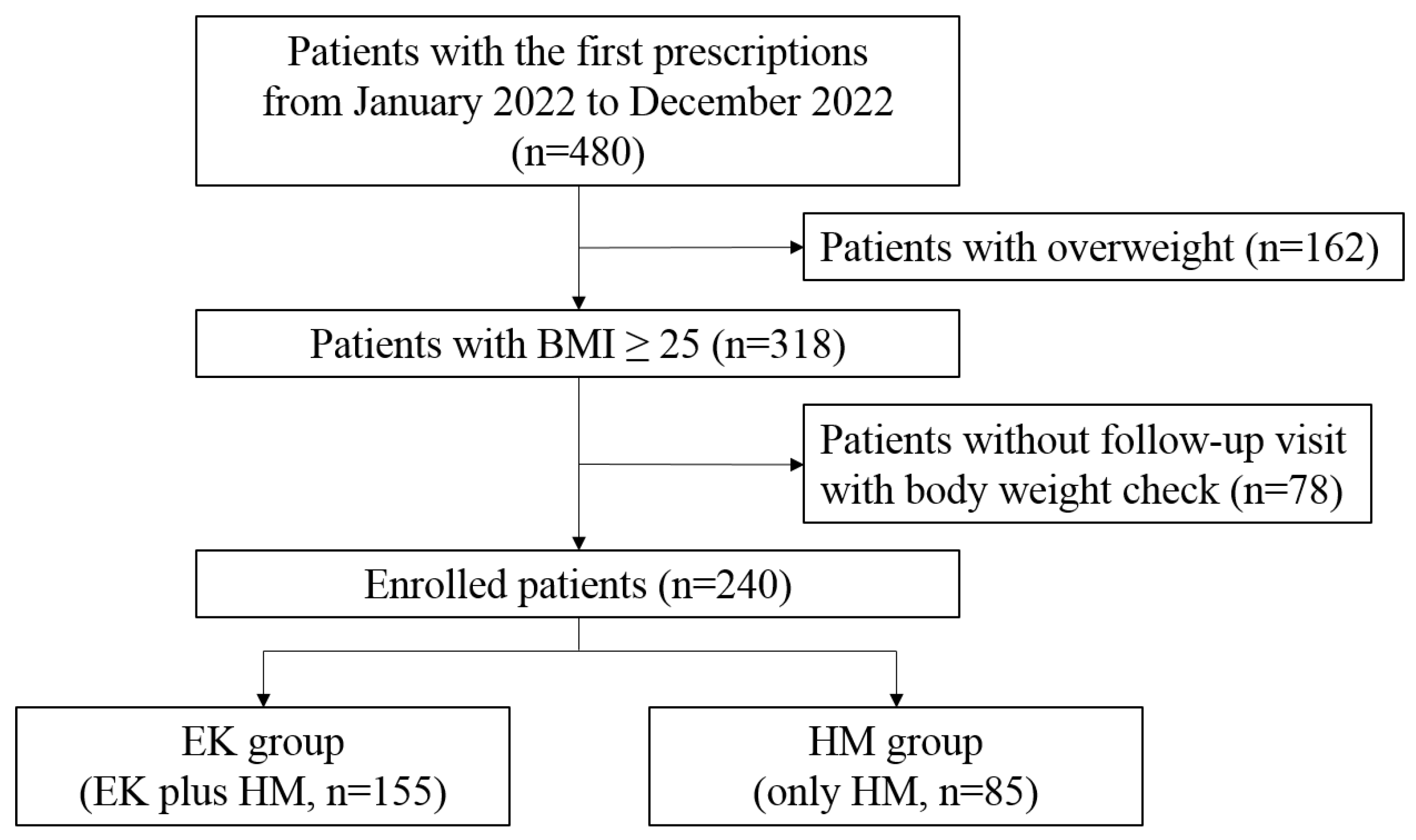

4.1.1. Study Design and Eligible Patients

4.1.2. EK Therapy and HM Treatment

4.1.3. Lifestyle Modification

4.2. Animal Study

4.2.1. Study Design, Animal and EK Preparation

4.2.2. Weight Measurements and Blood Analysis

4.2.3. Analysis of ATMs and Monocytes

4.2.4. Analysis of the Composition of the Fecal Microbiota

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wyatt, H.R. Update on treatment strategies for obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, K.W.; Abdul Ghani, R.; Cua, S.C.; Deerochanawong, C.; Fojas, M.; Hocking, S.; Lee, J.; Nam, T.Q.; Pathan, F.; Saboo, B.; et al. Obesity in South and Southeast Asia-A new consensus on care and management. Obes Rev 2023, 24, e13520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Iwaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, Y. ; NakayamaO. ; Makishima, M.; Matsuda, M.; Shimomura, I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2004, 114, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C.G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, L.; Lumeng, C.N. Properties and functions of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity. Immunology 2018, 155, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, G.; Xiang, L.X.; Luo, D.C.; Shao, J.Z. Occurrences and Functions of Ly6C(hi) and Ly6C(lo) Macrophages in Health and Disease. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 901672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.J.; West, N.P.; Cripps, A.W. Obesity, inflammation, and the gut microbiota. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015, 3, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Warmbrunn, M.V.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clement, K. Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders and the Microbiome: The Intestinal Microbiota Associated With Obesity, Lipid Metabolism, and Metabolic Health-Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Strategies. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 573–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, G.D.; Zhou, D.Q.; He, J.S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.F.; Xiao, C.L.; Peng, L.S. Clinical research on navel application of Shehuang Paste combined with Chinese herbal colon dialysis in treatment of refractory cirrhotic ascites complicated with azotemia. World J Gastroenterol 2006, 12, 7798–7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Shang, E.X.; Tang, Y.P.; Kai, J.; Cao, Y.J.; Zhou, G.S.; Tao, W.W.; Kang, A.; Su, S.L.; et al. The dosage-toxicity-efficacy relationship of kansui and licorice in malignant pleural effusion rats based on factor analysis. J Ethnopharmacol 2016, 186, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lei, F.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Hu, J.; Cheng, X.; Xing, D.; Hua, L.; Lin, R.; Du, L. [Effect of Euphorbia kansui on urination and kidney AQP2, IL-1beta and TNF-alpha mRNA expression of mice injected with normal saline]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2012, 37, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Li, R. Bioactive C21 Steroidal Glycosides from Euphorbia kansui Promoted HepG2 Cell Apoptosis via the Degradation of ATP1A1 and Inhibited Macrophage Polarization under Co-Cultivation. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.J.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Fang, L.; Cai, L.Y.; Yao, S.; Long, H.L.; Wu, W.Y.; Guo, D.A. Anti-proliferation activity of terpenoids isolated from Euphorbia kansui in human cancer cells and their structure-activity relationship. Chin J Nat Med 2017, 15, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Jang, Y.W.; Hyung, K.E.; Lee, D.K.; Hyun, K.H.; Park, S.Y.; Park, E.S.; Hwang, K.W. Therapeutic Effects of Methanol Extract from Euphorbia kansui Radix on Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis. J Immunol Res 2017, 2017, 7052560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sickle, M.D.; Duncan, M.; Kingsley, P.J.; Mouihate, A.; Urbani, P.; Mackie, K.; Stella, N.; Makriyannis, A.; Piomelli, D.; Davison, J.S.; et al. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science 2005, 310, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, L.Y.; He, H.P.; Leng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hao, X.J. Inhibition of 11b-HSD1 by tetracyclic triterpenoids from Euphorbia kansui. Molecules 2012, 17, 11826–11838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, E.Y. The effect of Hyungbangdojucksan-Gami and Kamsuchunilhwan on the obesity in the rats. J. Sasang Constitutional Medicine 2000, 12, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Na, H.Y.; Seol, M.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.C. Euphorbia kansui Attenuates Insulin Resistance in Obese Human Subjects and High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2017, 2017, 9058956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uneda, K.; Kawai, Y.; Yamada, T.; Kaneko, A.; Saito, R.; Chen, L.; Ishigami, T.; Namiki, T.; Mitsuma, T. Japanese traditional Kampo medicine bofutsushosan improves body mass index in participants with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, D.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.D. Effects of Gambisan in overweight adults and adults with obesity: A retrospective chart review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e18060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reum Lee, D.-Y.L. , Min-Ji Kim, Hyang-Sook Lee, Ka-Hye Choi, Seo-Young Kim, Young-Woo Lim, Young-Bae Park. Gamitaeeumjowee-Tang for weight loss in diabetic patients: A retrospective chart review. Journal of Korean Medicine 2021, 42, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Min, R.S.-H.J. , Jong-Soo Lee, Sung-Soo Kim, Hyun-Dae Shin. The Effect of Very Low Calorie Diet and Chegamuiyiin-tang on Bone Mineral Density. Journal of Korean Medicine for Obesity Research 2005, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, M.A.; Finucane, O.M.; Connaughton, R.M.; McMorrow, A.M.; Roche, H.M. Mechanisms of obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance: insights into the emerging role of nutritional strategies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratofil, R.M.; Kubes, P.; Deniset, J.F. Monocyte Conversion During Inflammation and Injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffray, C.; Fogg, D.; Garfa, M.; Elain, G.; Join-Lambert, O.; Kayal, S.; Sarnacki, S.; Cumano, A.; Lauvau, G.; Geissmann, F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science 2007, 317, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, J.; Ji, K.; Zhang, P. Bamboo shoot fiber prevents obesity in mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S.; Tappu, R.M.; Damms-Machado, A.; Huson, D.H.; Bischoff, S.C. Characterization of the Gut Microbial Community of Obese Patients Following a Weight-Loss Intervention Using Whole Metagenome Shotgun Sequencing. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0149564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulange, C.L.; Neves, A.L.; Chilloux, J.; Nicholson, J.K.; Dumas, M.E. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med 2016, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.F.; Cotter, P.D.; Healy, S.; Marques, T.M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Fouhy, F.; Clarke, S.F.; O’Toole, P.W.; Quigley, E.M.; Stanton, C.; et al. Composition and energy harvesting capacity of the gut microbiota: relationship to diet, obesity and time in mouse models. Gut 2010, 59, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravussin, Y.; Koren, O.; Spor, A.; LeDuc, C.; Gutman, R.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R.; Ley, R.E.; Leibel, R.L. Responses of gut microbiota to diet composition and weight loss in lean and obese mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012, 20, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, A.; Pfann, C.; Steinberger, M.; Hanson, B.; Herp, S.; Brugiroux, S.; Gomes Neto, J.C.; Boekschoten, M.V.; Schwab, C.; Urich, T.; et al. Lifestyle and Horizontal Gene Transfer-Mediated Evolution of Mucispirillum schaedleri, a Core Member of the Murine Gut Microbiota. mSystems 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everard, A.; Lazarevic, V.; Gaia, N.; Johansson, M.; Stahlman, M.; Backhed, F.; Delzenne, N.M.; Schrenzel, J.; Francois, P.; Cani, P.D. Microbiome of prebiotic-treated mice reveals novel targets involved in host response during obesity. ISME J 2014, 8, 2116–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total | EK group | HM group | P value |

| N | 240 | 155 | 85 | |

| Age (years) | 41.28 ± 12.17 | 41.75 ± 12.20 | 40.42 ± 12.14 | 0.442 |

| Male (%) | 29.58 | 34.19 | 21.18 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.6 ± 8.41 | 165.4 ± 8.78 | 163.3 ± 7.52 | 0.062 |

| Body weight (kg) | 81.25 ± 14.73 | 84.75 ± 15.38 | 74.88 ± 10.97 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.84 ± 4.12 | 30.85 ± 4.34 | 28.01 ± 2.94 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up duration (days) | 91.55 ± 66.77 | 93.30 ± 70.43 | 88.36 ± 59.78 | 0.903 |

| Fat weight (kg) | 32.27 ± 15.75 | 33.93 ± 17.89 | 28.31 ± 7.49 | <0.001 |

| Muscle weight (kg) | 27.91 ± 6.41 | 28.81 ± 6.60 | 25.80 ± 5.42 | <0.001 |

| Body fluid (kg) | 36.95 ± 7.76 | 38.09 ± 7.96 | 34.26 ± 6.58 | <0.001 |

| Smokers (%) | 16.35 | 18.71 | 12.05 | |

| Non-drinkers (%) | 41.66 | 38.06 | 51.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).