Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

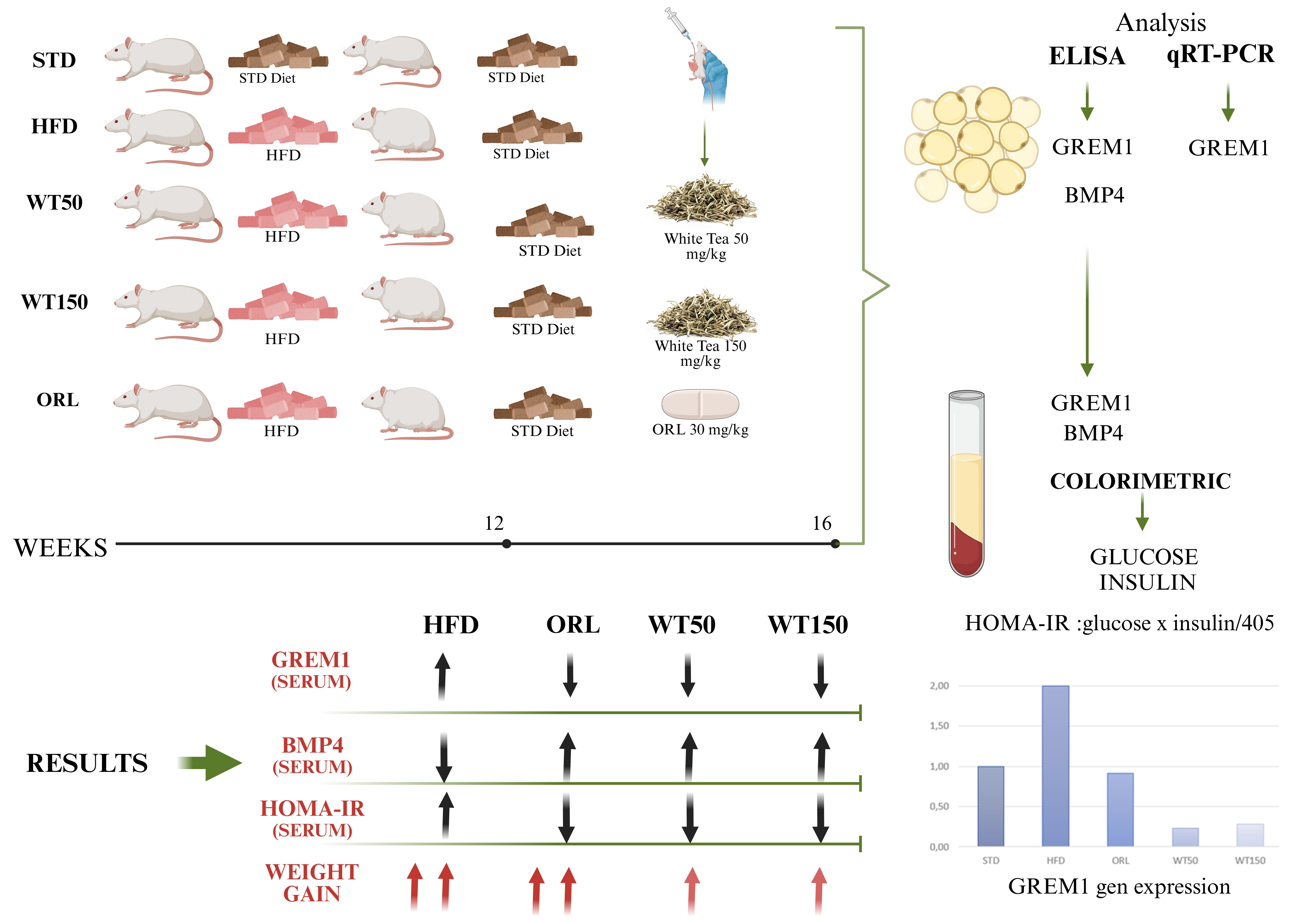

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Study Groups

2.2. Preparation of White Tea Samples

2.3. Preparation of Blood and Tissue Specimens

2.4. Analysis of Samples

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. HPLC Content and Total Polyphenol/Flavonoid Capacity of White Tea

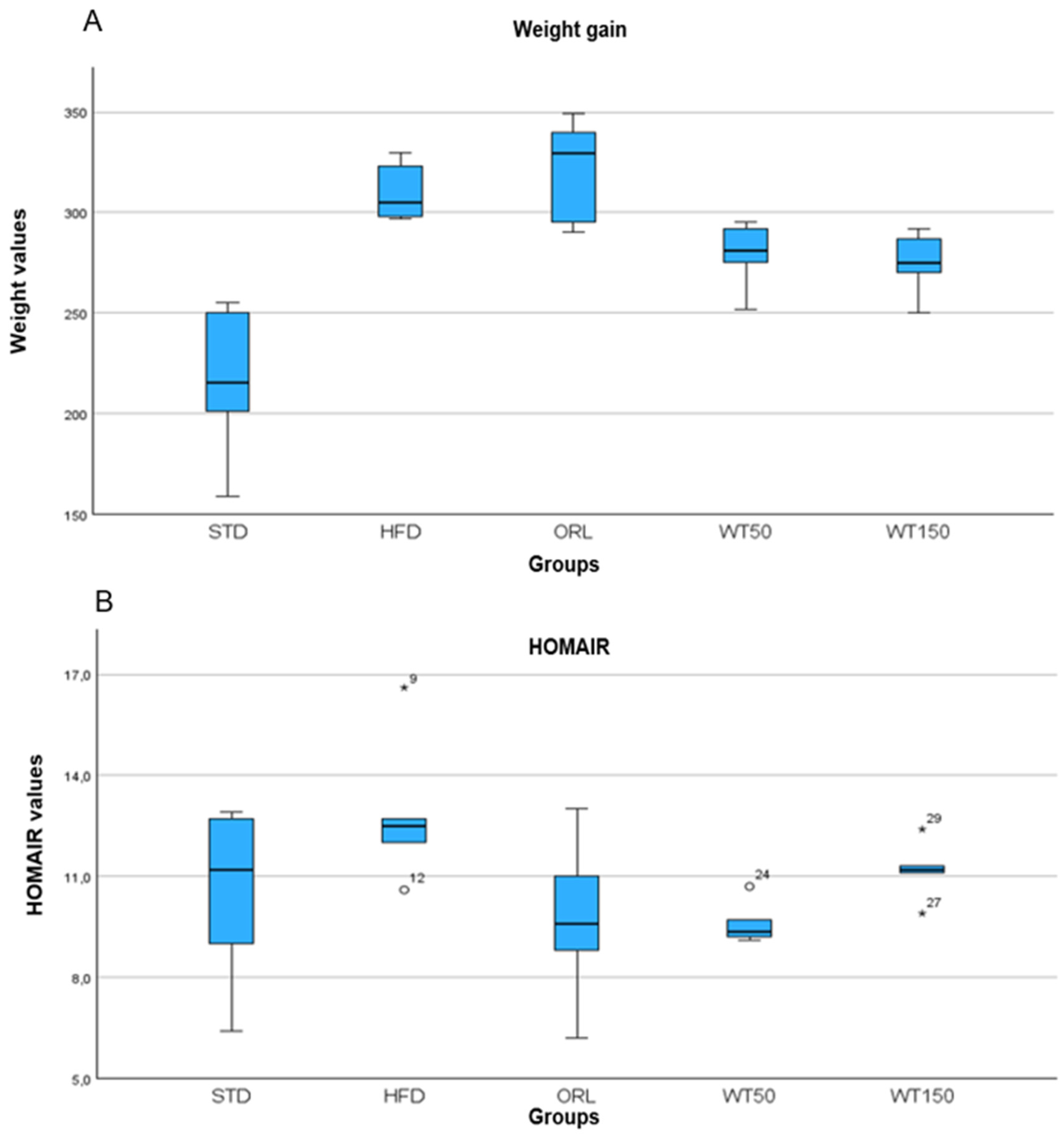

3.2. Weight gain and HOMA-IR index

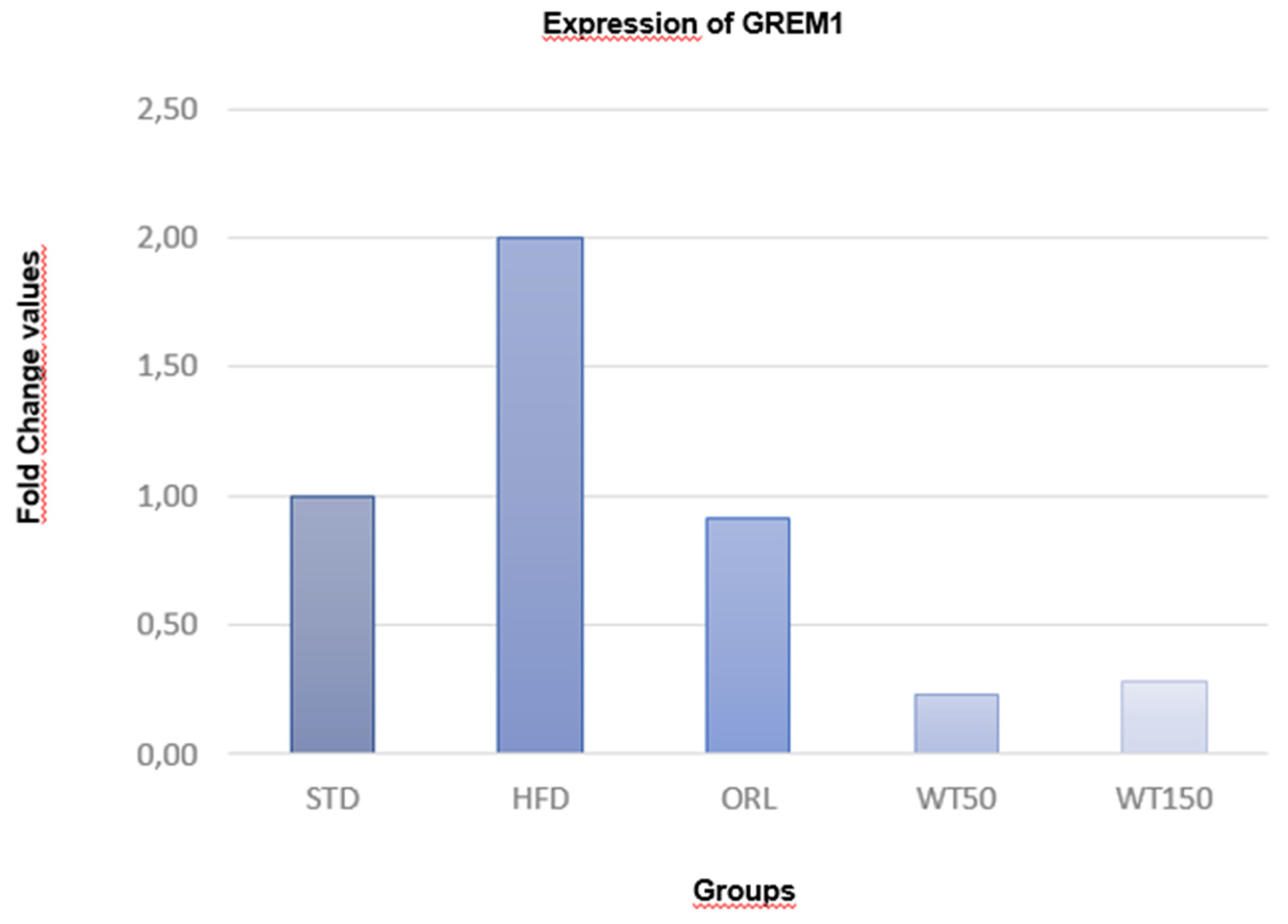

3.3. GREM1 Expression in Visceral Adipose Tissue

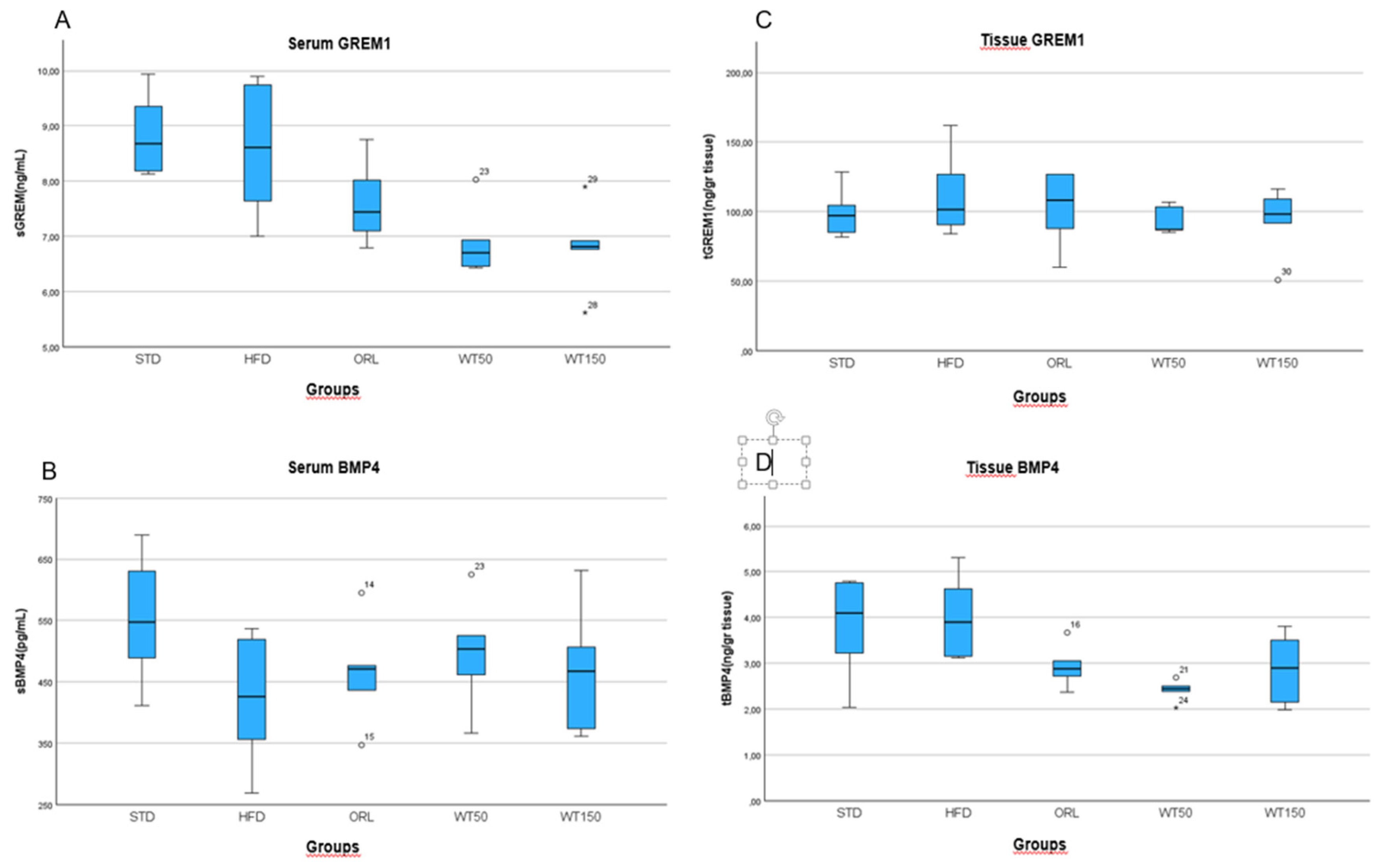

3.4. Serum and Tissue Protein Levels of GREM1 and BMP-4.

3.5. Correlation Analysis of GREM1 and BMP4

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghaben AL, Scherer PE. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2019;20(4):242-58.

- Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. State of the art paper Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Archives of medical science. 2013;9(2):191-200.

- Kahn CR, Wang G, Lee KY. Altered adipose tissue and adipocyte function in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2019;129(10):3990-4000.

- Park A, Kim WK, Bae K-H. Distinction of white, beige and brown adipocytes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. World journal of stem cells. 2014;6(1):33.

- Vishnoi H, Bodla RB, Kant R, Bodla R. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) and its antioxidant property: A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2018;9(5):1723-36.

- Sanlier N, Atik İ, Atik A. A minireview of effects of white tea consumption on diseases. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2018;82:82-8.

- Xu R, Yang K, Li S, Dai M, Chen G. Effect of green tea consumption on blood lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr J. 2020 May 20;19(1):48. PMID: 32434539; PMCID: PMC7240975. [CrossRef]

- Huner Yigit M, Atak M, Yigit E, Topal Suzan Z, Kivrak M, Uydu HA. White Tea Reduces Dyslipidemia, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in the Aortic Arch in a Model of Atherosclerosis Induced by Atherogenic Diet in ApoE Knockout Mice. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Dec 17;17(12):1699. PMID: 39770544; PMCID: PMC11679696. [CrossRef]

- Abe SK, Inoue M. Green tea and cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a review of the current epidemiological evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021 Jun;75(6):865-876. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32820240; PMCID: PMC8189915. [CrossRef]

- Kišonaitė M, Wang X, Hyvönen M. Structure of Gremlin-1 and analysis of its interaction with BMP-2. Biochem J. 2016 Jun 1;473(11):1593-604. Epub 2016 Apr 1. PMID: 27036124; PMCID: PMC4888461. [CrossRef]

- Gustafson B, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, Hoffmann JM, Svensson PA, Grimsby J, Rondinone C, Smith U. BMP4 and BMP Antagonists Regulate Human White and Beige Adipogenesis. Diabetes. 2015 May;64(5):1670-81. Epub 2015 Jan 20. PMID: 25605802. [CrossRef]

- Qian SW, Tang Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang YY, Huang HY, Xue RD, Yu HY, Guo L, Gao HD, Liu Y, Sun X, Li YM, Jia WP, Tang QQ. BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Feb 26;110(9):E798-807. Epub 2013 Feb 6. PMID: 23388637; PMCID: PMC3587258. [CrossRef]

- Elsen M, Raschke S, Tennagels N, Schwahn U, Jelenik T, Roden M, Romacho T, Eckel J. BMP4 and BMP7 induce the white-to-brown transition of primary human adipose stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014 Mar 1;306(5):C431-40. Epub 2013 Nov 27. PMID: 24284793. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann JM, Grünberg JR, Church C, Elias I, Palsdottir V, Jansson JO, Bosch F, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, Smith U. BMP4 Gene Therapy in Mature Mice Reduces BAT Activation but Protects from Obesity by Browning Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017 Aug 1;20(5):1038-1049. PMID: 28768190. [CrossRef]

- Hammarstedt A, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, Nerstedt A, Smith U. Impaired Adipogenesis and Dysfunctional Adipose Tissue in Human Hypertrophic Obesity. Physiol Rev. 2018 Oct 1;98(4):1911-1941. PMID: 30067159. [CrossRef]

- Hedjazifar S, Khatib Shahidi R, Hammarstedt A, Bonnet L, Church C, Boucher J, Blüher M, Smith U. The Novel Adipokine Gremlin 1 Antagonizes Insulin Action and Is Increased in Type 2 Diabetes and NAFLD/NASH. Diabetes. 2020 Mar;69(3):331-341. Epub 2019 Dec 27. PMID: 31882566. [CrossRef]

- Park A, Kim WK, Bae KH. Distinction of white, beige and brown adipocytes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2014 Jan 26;6(1):33-42. PMID: 24567786; PMCID: PMC3927012. [CrossRef]

- Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Arch Med Sci. 2013 Apr 20;9(2):191-200. Epub 2013 Feb 10. PMID: 23671428; PMCID: PMC3648822. [CrossRef]

- Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutrition research reviews. 2010;23(2):270-99.

- Yılmaz HK, Türker M, Kutlu EY, Mercantepe T, Pınarbaş E, Tümkaya L, Atak M. Investigation of the effects of white tea on liver fibrosis: An experimental animal model. Food Sci Nutr. 2024 Jan 30;12(4):2998-3006. PMID: 38628196; PMCID: PMC11016422. [CrossRef]

- Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutrition research reviews. 2010;23(2):270-99.

- Huner Yigit, M. Huner Yigit, M., Atak, M., Yigit, E., Topal Suzan, Z., Kivrak, M., & Uydu, H. A. (2024). White Tea Reduces Dyslipidemia, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in the Aortic Arch in a Model of Atherosclerosis Induced by Atherogenic Diet in ApoE Knockout Mice. Pharmaceuticals, 17(12), 1699.

- Grillo E, Ravelli C, Colleluori G, D’Agostino F, Domenichini M, Giordano A, Mitola S. Role of gremlin-1 in the pathophysiology of the adipose tissues. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2023 Feb;69:51-60. Epub 2022 Sep 14. PMID: 36155165. [CrossRef]

- Dashwood WM, Orner GA, Dashwood RH. Inhibition of beta-catenin/Tcf activity by white tea, green tea, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): minor contribution of H(2)O(2) at physiologically relevant EGCG concentrations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002 Aug 23;296(3):584-8. PMID: 12176021. [CrossRef]

- Teiten MH, Gaascht F, Dicato M, Diederich M. Targeting the wingless signaling pathway with natural compounds as chemopreventive or chemotherapeutic agents. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012 Jan;13(1):245-54. PMID: 21466435. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann JM, Grünberg JR, Church C, Elias I, Palsdottir V, Jansson JO, Bosch F, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, Smith U. BMP4 Gene Therapy in Mature Mice Reduces BAT Activation but Protects from Obesity by Browning Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep. 2017 Aug 1;20(5):1038-1049. PMID: 28768190. [CrossRef]

- Ivet Elias, Sylvie Franckhauser, Tura Ferré, Laia Vilà, Sabrina Tafuro, Sergio Muñoz, Carles Roca, David Ramos, Anna Pujol, Efren Riu, Jesús Ruberte, Fatima Bosch; Adipose Tissue Overexpression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Protects Against Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 1 July 2012; 61 (7): 1801–1813.

- Kapoor VN, Müller S, Keerthivasan S, Brown M, Chalouni C, Storm EE, Castiglioni A, Lane R, Nitschke M, Dominguez CX, Astarita JL, Krishnamurty AT, Carbone CB, Senbabaoglu Y, Wang AW, Wu X, Cremasco V, Roose-Girma M, Tam L, Doerr J, Chen MZ, Lee WP, Modrusan Z, Yang YA, Bourgon R, Sandoval W, Shaw AS, de Sauvage FJ, Mellman I, Moussion C, Turley SJ. Gremlin 1+ fibroblastic niche maintains dendritic cell homeostasis in lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. 2021 May;22(5):571-585. Epub 2021 Apr 26. PMID: 33903764. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhou F, Wen M, Jiang S, Long P, Ke JP, Han Z, Zhu M, Zhou Y, Zhang L. LC-MS and GC-MS based metabolomics analysis revealed the impact of tea trichomes on the chemical and flavor characteristics of white tea. Food Res Int. 2024 Sep;191:114740. Epub 2024 Jul 8. PMID: 39059930. [CrossRef]

- Moqaddasi HR, Singh A, Mukherjee S, Rezai F, Gupta A, Srivastava S, Sridhar SB, Ahmad I, Dwivedi VD, Kumar S. Influencing hair regrowth with EGCG by targeting glycogen synthase kinase-3β activity: a molecular dynamics study. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2025 Apr;45(2):95-106. Epub 2025 Feb 18. PMID: 39964119. [CrossRef]

- Prasanth MI, Sivamaruthi BS, Cheong CSY, Verma K, Tencomnao T, Brimson JM, Prasansuklab A. Role of Epigenetic Modulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Implications of Phytochemical Interventions. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024 May 15;13(5):606. PMID: 38790711; PMCID: PMC11118909. [CrossRef]

| Number | Compound Name |

Retention Time (Min) |

Concentration (n = 2, µg/g) |

| 1 | Gallic acid | 3.202 | 5.55 ± 0.61 |

| 2 | Epigallocatechin | 4.499 | 261.4 ± 3.59 |

| 3 | Catechin | 5.488 | - |

| 4 | Caffeine | 7.750 | 101.51 ± 2.61 |

| 5 | Epigallocatechin 3-gallate | 8.678 | 119.8 ± 2.31 |

| 6 | Epicatechin | 9.800 | - |

| 7 | Epicatechin 3-gallate | 15.916 | 46.36 ± 1.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).