1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and its associated complications represent a major global health burden, with prevalence rising at an alarming rate. Recent estimates predict that by 2050, approximately 1.31 billion individuals will be living with diabetes, an almost two-and-a-half-fold increase from 529 million in 2021 [

1]. A 2019 prospective study from Kerala reported a cumulative incidence of 21.9% for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and 36.7% for prediabetes, with nearly 60% of individuals with impaired glucose progressing to T2DM, highlighting an alarming epidemic trend in the region [

2]. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are among the most serious complications of diabetes, contributing significantly to mortality, hospitalizations, and lower-extremity amputations [

3,

4]. While peripheral neuropathy and peripheral artery disease are well-established clinical risk factors for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), social determinants such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location also significantly influence DFU risk and outcomes [

5].

In India, the prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) among individuals with diabetes ranges from 4% to 10%, with hospital-based studies often reporting higher rates. In Kerala, where the burden of diabetes is notably high, a hospital-based study involving 277 patients reported a 41.51% prevalence of non-healing DFUs [

6]. Further emphasizing the regional burden, a more recent study found that 51.7% of the diabetic cohort exhibited diabetic foot syndrome, and 18% had active DFUs [

7]. DFU is characterised by neuropathy, vascular insufficiency, infection, and impaired healing [

8,

9]. In diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) and other chronic wounds, the normal, systematic sequence of wound healing is often disrupted. Healing may be arrested at one or multiple stages due to a lack of synchrony in the repair process [

10]. Vitamin D plays a crucial immunomodulatory role by reducing inflammation, enhancing antimicrobial defence, and supporting tissue homeostasis, functions that are highly relevant to wound healing. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a nuclear receptor located on chromosome 12 (12q13.11) and is responsible for the 1α,25(OH)2D signaling. Polymorphisms in the VDR gene can impair these regulatory pathways, potentially contributing to chronic DFUs by promoting excessive inflammation, reducing angiogenesis, and weakening immune responses [

11].

Growing evidence suggests that vitamin D plays a crucial role in the prevention and management of diabetes mellitus. Since the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene and 1-α-hydroxylase, the vitamin D metabolizing enzyme, are present in β-cells, vitamin D influences the synthesis and secretion of insulin [

12,

13,

14]. Several studies have reported that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels are significantly lower in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) compared to diabetic individuals without foot ulcers, and these lower levels have been associated with increased ulcer severity and impaired wound healing [

15,

16]. Furthermore, a higher risk of developing DFU has been linked to specific vitamin D receptor (VDR) genetic variants, particularly rs2228570 [

17]. Additionally, other studies have shown that increased oxidative stress observed in DFU patients is associated with VDR gene polymorphisms rs7975232 and rs2228570, suggesting a potential gene-environment interaction in the pathogenesis of DFU [

18,

19]. Despite the growing body of evidence, studies examining serum vitamin D levels and VDR gene polymorphisms in the Indian population remain limited [

20]. In the present study, we analyzed serum vitamin D levels and VDR gene polymorphisms among individuals with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without foot ulcers, and non-diabetic controls from Kerala, India. The most frequently reported VDR single-nucleotide polymorphisms, rs7975232 (ApaI), rs731236 (TaqI), rs1544410 (BsmI), and rs2228570 (FokI) were selected for investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the Thiruvananthapuram district of Kerala. Sample collection took place from September 2021 to September 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the research proposal was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the General Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram (Approval No. 13/21/11/19-GHEC; approval date:21-11-2021). The sample size was based on a previous study by Selvarajan et al. (2021)(21), which investigated the association of vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphisms with serum 25(OH)D levels in type 2 diabetes patients from Southern India. Assuming a conservative mean difference of 5 ng/mL in serum 25(OH)D levels across VDR genotypes and a pooled standard deviation of 11 ng/mL, a minimum of 76 participants per group was required to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level. To ensure higher statistical power (90%) and to accommodate subgroup and genotype frequency analyses, 336 participants were included, with 112 individuals in each group (DFU, DM and healthy control). DFU patients were recruited from the outpatient departments of Saraswathy Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram, and Sree Narayana Trust Medical Mission Hospital, Kollam, with the assistance of the respective medical practitioners. Diabetic foot ulcers were classified using the Wagner grading system and only Grade 2 and Grade 3 ulcers with neuroischemic or neuropathic characteristics were included in the study. In the diabetes group without ulcers, individuals with no history of current or previous non-healing ulcers were enrolled. Participants receiving vitamin D supplementation were excluded. The control group comprised healthy individuals aged 45–64 years. General exclusion criteria included age below 45 or above 64 years, current or recent use of vitamin D supplements, and the presence of any acute or terminal illness other than diabetes mellitus. The DM category individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) and those without foot ulcers were recruited from government Family Health Centres across the district. Non-diabetic healthy controls were enrolled from the general community of Thiruvananthapuram and Kollam districts.

All participants were fully informed about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each individual before data and blood sample collection. A total of 4 ml of blood was collected intravenously into EDTA-containing vacutainers. Of this, 0.5 ml of whole blood was used for DNA isolation. The remaining blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 30 minutes to separate plasma, which was then stored at -80 °C until further analysis. Additionally, 2 ml of blood was collected into sodium fluoride vacutainers for glucose estimation. Vitamin D estimation was done using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). For HPLC, methanol and acetonitrile of HPLC grade were purchased from Merck. HPLC standard 25(OH)D was purchased from Sigma (cat no.H4014). The procedure involved the following steps. Blood samples were first centrifuged to separate the serum. To 500 µl of the serum sample, 350 µl of methanol–2-propanol was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 30 seconds. The sample was then extracted three times with 2 ml of hexane. After extraction, the phases were separated by centrifugation, and the upper organic layer was carefully transferred to a clean tube. This extract was dried under a stream of nitrogen, and the resulting residue was dissolved in 100 µl of the mobile phase. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was carried out using a C18 column maintained at 40 °C, with detection at 265 nm. Vitamin D status was assessed by quantifying plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). The concentration of 25(OH)D was determined based on the area under the curve corresponding to the retention time of the known HPLC standard. According to clinical classification guidelines, a 25(OH)D level of less than 20 ng/mL was considered vitamin D deficient, levels between 20 and 29 ng/mL were classified as insufficient, and levels equal to or greater than 30 ng/mL were considered sufficient. Furthermore, values below 5 ng/mL (equivalent to <12.5 nmol/L) were defined as severe vitamin D deficiency. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and methanol in a ratio of 20:80.

Genomic DNA was isolated from 200 µL of whole blood using a commercial DNA isolation kit (Primordia Nucleosieve® blood DNA extraction kit, Cat. No.PMD006 ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SNP genotyping was performed using TaqMan® allele-specific probes designed for the selected polymorphisms. The following vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped: rs7975232 (ApaI), rs731236 (TaqI), rs1544410 (BsmI), and rs2228570 (FokI). Genotyping of SNPs was performed using real-time PCR with a total reaction volume of 5 µL. The reaction mix contained 2.5 µL of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 0.25 µL of TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (probe), 1.25 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1 µL of genomic DNA. The thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 1 minute. Reactions were run on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System, and genotypes were determined using the accompanying QuantStudio™ Design and Analysis Software.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software Version 16 and Python 3.11.13, utilizing appropriate libraries such as SciPy and Pandas. The chi-square goodness-of-fit test was applied to assess whether the genotype distributions of each SNP conformed to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) within the control group. To evaluate the association between vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms and the presence of diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), binary logistic regression analysis was conducted, yielding odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each SNP. Additionally, linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype analyses were performed using Python to examine potential genetic linkages between SNP loci and to identify haplotype structures associated with DFU risk.

3. Results

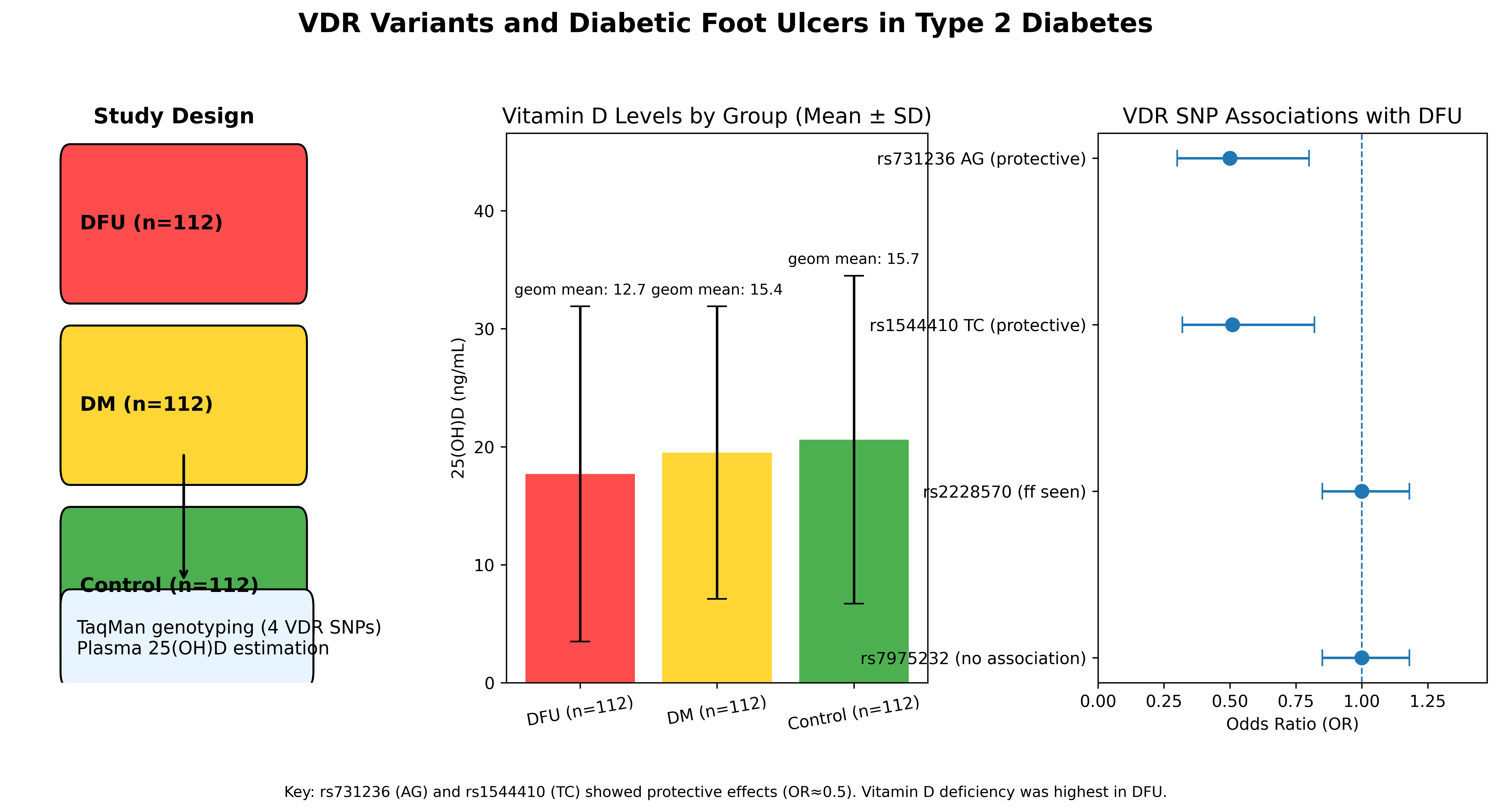

The present study included a total of 336 participants, comprising 112 patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), 112 individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) without foot ulcers, and 112 healthy non-diabetic controls. Both male and female participants were enrolled across all groups. The overall mean age of the study population was 59.12 ± 11.22 years. The serum vitamin D levels were 17.7 ± 14.3 ng/mL in the DFU group, 19.5 ± 12.3 ng/mL in the diabetes mellitus (DM) group, and 20.6 ± 14.0 ng/mL in the healthy control group. The geometric mean of serum vitamin D levels was used to account for the skewed distribution of values. Based on this measure, participants in all three groups- non-diabetic controls, diabetes mellitus (DM), and diabetic foot ulcer (DFU)

- fell within the vitamin D

-deficient category, indicating a widespread deficiency across the study population. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

All four VDR SNPs-rs7975232, rs731236, rs1544410, and rs2228570-exhibited minor allele frequencies (MAF) above 0.2, indicating that they are polymorphic and thus suitable for association analysis. Furthermore, all SNPs were found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), with p-values > 0.05, suggesting no significant deviation from expected genotype frequencies in the study population (

Table 2).

The genotype distributions across the DFU, DM, and control groups are summarized in

Table 3. The AG genotype of rs731236 was significantly associated with a reduced risk of developing diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) when compared with both the diabetes mellitus (DM) group (p = 0.0186, OR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29–0.88) and non-diabetic controls (p = 0.0204, OR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.28–0.89), indicating a strong protective association. Similarly, the TC genotype of rs1544410 showed a significant protective effect against DFU when compared with controls (p = 0.0219, OR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29–0.90).

In addition, the AA genotype of rs731236 (p = 0.049, OR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.04–3.50) and the TT genotype of rs1544410 (p = 0.0511, OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.01–3.84) were marginally significant, suggesting a possible increased risk of DFU associated with these genotypes. In contrast, no significant associations were observed for any genotypes of rs2228570 and rs7975232 in comparisons with either DM or control groups.

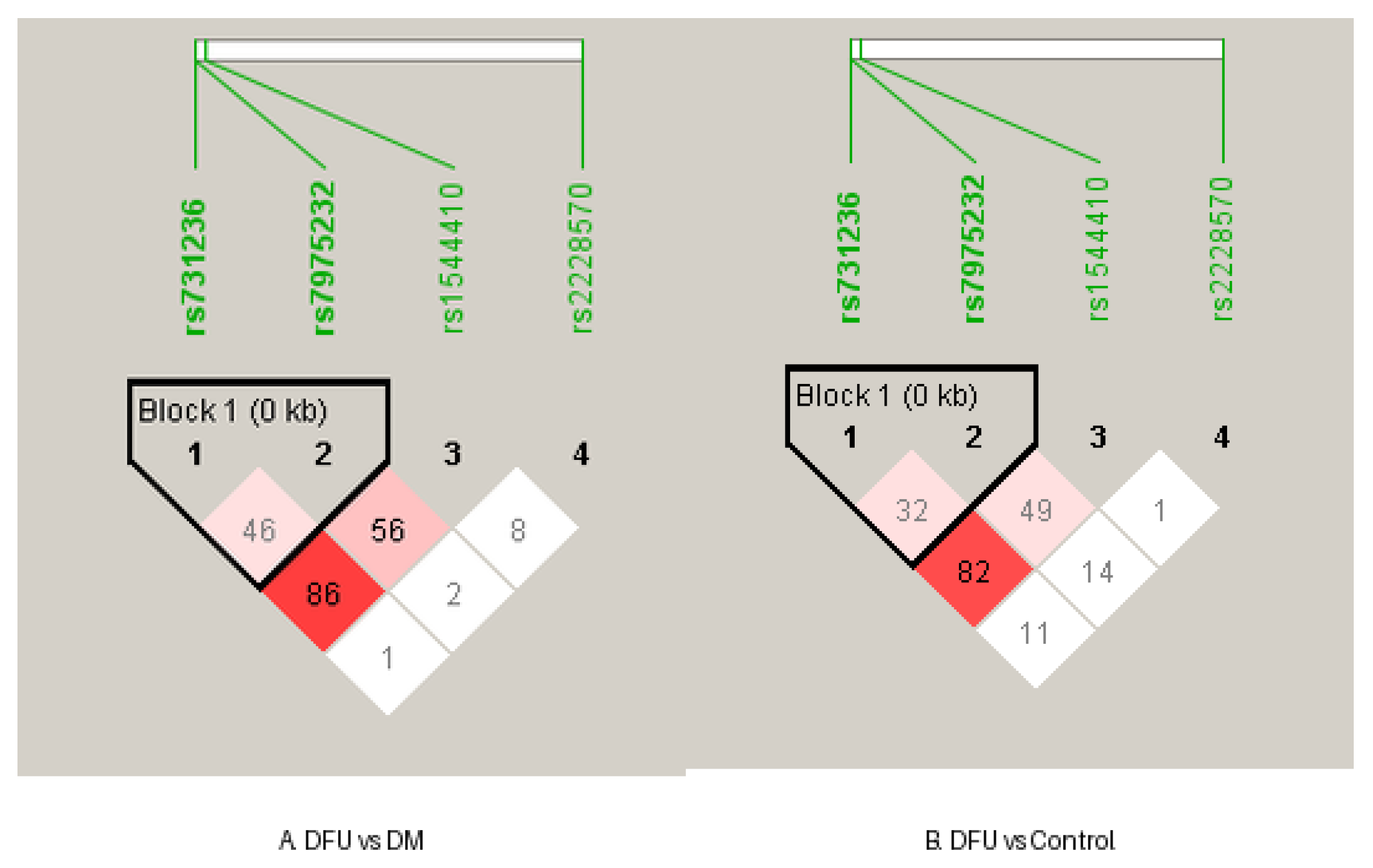

In the DFU group, a strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) was observed between rs731236 and rs1544410 (D′ = 0.8803; r² = 0.5327), whereas other SNP pairs exhibited weaker LD. Similarly, the DM group showed strong LD between the same SNPs (D′ = 0.8727; r² = 0.4962), while in the control group, the correlation between rs731236 and rs1544410 was minimal (r² = 0.0455), despite D′ = 1, suggesting low predictive value due to allele frequency differences. Additionally, the DM group exhibited increased LD between rs2228570 and rs1544410 (D′ = 1; r² = 0.4688), which was notably higher than that observed in both the DFU and control groups (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The VDR is a ligand-inducible transcription factor that regulates various physiological processes, including calcium homeostasis and immune system function. It becomes activated upon binding with the biologically active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D₃ (calcitriol), leading to the modulation of gene expression involved in these critical pathways [

9]. In the present study, we compared plasma vitamin D levels among individuals with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), those with diabetes mellitus (DM), and non-diabetic controls from the Kerala population. Although plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels were lower in the DM and DFU groups compared to the control group, these differences were not statistically significant. A similar trend was previously reported in a South Indian population by Kurian SJ et al., 2024 [

16]. Notably, all three groups in our study exhibited vitamin D deficiency, highlighting a significant and potentially overlooked public health concern within the Kerala population. This finding emphasizes the importance of screening, targeted supplements, and community-level interventions in this region. Additionally, we analyzed the most commonly studied single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene-rs7975232, rs731236, rs1544410, and rs2228570-to assess their association with DFU susceptibility.

The Fok1 SNP (rs2228570 A>G) is located in exon 2, specifically at the start codon of the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) gene. This polymorphism affects the translation initiation site, resulting in the production of either a shorter VDR protein (comprising 424 amino acids) or a longer form (containing 427 amino acids). The shorter form, associated with the F allele, is considered to be more transcriptionally active. Mutations at rs2228570 can influence calcium homeostasis, insulin secretion, and immune regulation, thereby playing a potential role in the development of various metabolic and immune

-related diseases [

21,

22]. In the present study, neither rs2228570 nor rs7975232 showed a statistically significant association with any of the study groups (DFU, DM, or controls), suggesting that these polymorphisms may not be directly linked to DFU susceptibility in the Kerala population. Notably, the GG genotype (ff) of rs2228570 was observed in 57.6% of participants, indicating a potential prevalence of the less active variant of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) protein. This high frequency of the ff genotype, coupled with the widespread vitamin D deficiency observed across both control and case groups, may reflect an underlying genetic influence on vitamin D metabolism in this population. To validate these findings and better understand the genetic contribution, we recommend large-scale population-based screening of rs2228570 and related VDR SNPs in the Kerala population. The other three SNPs, viz., rs7975232 (ApaI), rs731236 (TaqI), and rs1544410 (BsmI), are located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the VDR gene. Although these polymorphisms do not directly affect the amino acid sequence of the VDR protein, they may influence mRNA stability, leading to altered VDR gene expression. Such changes can impact vitamin D-mediated immune modulation, particularly by affecting the production of key cytokines such as interleukin

-10 (IL-10) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

23]. The SNPs rs731236 and rs1544410 have shown statistically significant association with the DFU in our study. The heterozygous genotype of rs731236 (AG) and rs1544410(TC) is found to be protective in DFU, suggesting a possible heterozygote advantage. These findings support the hypothesis that VDR genetic variation may modulate DFU risk, potentially through mechanisms involving altered receptor activity, gene expression regulation, or downstream immunomodulatory effects. Importantly, strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) between rs731236 and rs1544410 was observed in both the DFU (D′ = 0.8803; r² = 0.5327) and DM (D′ = 0.8727; r² = 0.4962) groups, indicating that these SNPs are likely co-inherited as part of a shared haplotype block in individuals with disease. In contrast, the control group exhibited minimal correlation (r² = 0.0455) between these loci, despite a high D′ value (D′ = 1), suggesting that allele frequencies differ substantially in unaffected individuals, thereby reducing the predictive value of one SNP for the other in the healthy population. These findings suggest a potential shift in haplotype structure and allele co-inheritance patterns among disease groups compared to healthy controls, particularly in the vicinity of the VDR gene region. Very few studies have focused on VDR gene polymorphism and diabetic foot ulcers. The most consistent associations were observed with Fok1 and Apa1 variants [

16,

18,

19,

24].Our study findings with association of Taq1 and Bsm1 SNPs with protective heterozygous effects and notable LD patterns- add new, valuable data from the Kerala population, where these SNPs have been understudied. Additionally, the AA genotype of rs731236 and the TT genotype of rs1544410 showed marginally significant associations with increased risk of diabetic foot ulcers. Given that vitamin D functions both as a nutrient and a pro-hormone, these findings support the integration of nutritional assessment with genetic screening to personalize preventive strategies. The lowest 25(OH)D levels were observed in the DFU group, further reinforcing the importance of routine vitamin D screening as part of comprehensive diabetic care. Overall, this study underscores the need for a multidimensional approach- one that incorporates nutritional interventions, genetic screening, and public health policy—to reduce DFU risk and improve metabolic health in regions with a high burden of vitamin D deficiency and diabetes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among individuals with diabetic foot ulcers, diabetes mellitus without foot ulcers, and non-diabetic controls in the Kerala population. Our findings indicate that two VDR gene polymorphisms-rs731236 and rs1544410-are significantly associated with DFU, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition linked to vitamin D receptor function. In contrast, rs2228570 and rs7975232 showed no significant association with the condition. These results underscore the potential role of VDR gene variants in the pathogenesis of DFU and support the need for further studies to explore their functional implications and utility as genetic markers in risk stratification.

Author Contributions

RR conceived the study design, collected the samples, executed the experiments, performed data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. SKT contributed to the study design and manuscript review. ATS contributed to the study design, performed the sample size calculation, and participated in manuscript review. SJ contributed to the study design, provided funding support, and reviewed the draft. STV contributed to the study design, provided overall study oversight, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to ethical restrictions related to participant confidentiality and the conditions of the Institutional Ethics Committee approval, the raw human participant data cannot be made publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the participants involved in this study. We also thank the staff of Saraswathy Hospital, Thiruvananthapuram; Sree Narayana Trust Medical Mission Hospital, Kollam; and the District Medical Office, Thiruvananthapuram, for their valuable support and cooperation. This study was supported by extramural funding to Dr. Sara Jones from the Department of Science and Technology, Science and Engineering Research Board (DST-SERB), Government of India (Grant No.: CRG/2021/007773), and the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

References

- The L. Diabetes: a defining disease of the 21st century. Lancet. 2023;401(10394):2087.

- Vijayakumar G, Manghat S, Vijayakumar R, Simon L, Scaria LM, Vijayakumar A, et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes in Kerala, India: results from a 10-year prospective cohort. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):140. [CrossRef]

- McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, Epidemiology, and Disparities in the Burden of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(1):209-21. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2367-75.

- Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Abraham S, Jyothylekshmy V, Menon A. Epidemiology of diabetic foot complications in a podiatry clinic of a tertiary hospital in South India. Indian Journal of Health Sciences and Biomedical Research (KLEU). 2015;8(1). [CrossRef]

- James JJ, Vargese SS, Raju AS, Johny V, Kuriakose A, Mathew E. Burden of diabetic foot syndrome in rural community: Need for screening and health promotion. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(9):5546-50. [CrossRef]

- Reiber GE, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ, del Aguila M, Smith DG, Lavery LA, Boulton AJM. Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):157–62. [CrossRef]

- Carlberg C, Seuter S. A genomic perspective on vitamin D signaling. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(9):3485–94.

- Shaw TJ, Martin P. Wound repair at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 18):3209-13.

- Daryabor G, Gholijani N, Kahmini FR. A review of the critical role of vitamin D axis on the immune system. Exp Mol Pathol. 2023;132-133:104866. [CrossRef]

- Thorand B, Zierer A, Huth C, Linseisen J, Meisinger C, Roden M, et al. Effect of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D on risk for type 2 diabetes may be partially mediated by subclinical inflammation: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(10):2320-2.

- Pittas AG, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D and diabetes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1-2):425-9.

- Wu Y, Ding Y, Tanaka Y, Zhang W. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(11):1185-200. [CrossRef]

- Tang Y, Huang Y, Luo L, Xu M, Deng D, Fang Z, et al. Level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and vitamin D receptor in diabetic foot ulcer and factor associated with diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):30. [CrossRef]

- Kurian SJ, Baral T, Benson R, Munisamy M, Saravu K, Rodrigues GS, et al. Association of vitamin D status and vitamin D receptor polymorphism in diabetic foot ulcer patients: A prospective observational study in a South-Indian tertiary healthcare facility. Int Wound J. 2024;21(8):e70027. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Zhang LX, Wang YT, Li Y, Chen Md HL. Genetic Polymorphisms and the Risk of Diabetic Foot: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21(4):574-87.

- Klashami ZN, Ahrabi NZ, Ahrabi YS, Hasanzad M, Asadi M, Amoli MM. The vitamin D receptor gene variants, ApaI, TaqI, BsmI, and FokI in diabetic foot ulcer and their association with oxidative stress. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(9):8627-39. [CrossRef]

- Soroush N, Radfar M, Hamidi AK, Abdollahi M, Qorbani M, Razi F, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene FokI variant in diabetic foot ulcer and its relation with oxidative stress. Gene. 2017;599:87-91. [CrossRef]

- Aravindhan S, Almasoody MFM, Selman NA, Andreevna AN, Ravali S, Mohammadi P, et al. Vitamin D Receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes: evidence from a meta-regression and meta-analysis based on 47 studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2021;20(1):845-67. [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan S, Srinivasan A, Surendran D, Mathaiyan J, Kamalanathan S. Association of genetic polymorphisms in vitamin D receptor (ApaI, TaqI and FokI) with vitamin D and glycemic status in type 2 diabetes patients from Southern India. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 2021;36(3):183-7. [CrossRef]

- van Etten E, Gysemans C, Branisteanu DD, Verstuyf A, Bouillon R, Overbergh L, et al. Novel insights in the immune function of the vitamin D system: synergism with interferon-beta. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3-5):546-51. [CrossRef]

- Fronczek M, Osadnik T, Banach M. Impact of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms in selected metabolic disorders. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2023;26(4):316-22.

- Raflis R, Yuwono HS, Yanwirasti Y, Decroli E. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphism FokI and 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Levels among Indonesian Diabetic Foot Patients. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;8(A):846-51. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).