1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, characterized by irregular and disorganized atrial electrical activity that suppresses the normal sinus rhythm. AF poses serious health implications for affected individuals and a considerable burden for societies, e.g., new estimates suggest that 10.55 million U.S. adults (about 4.5–5% of the adult population) live with AF [

1]. Atrial fibrillation is a major risk of thromboembolic stroke, heart failure and mortality [

2]. Multiple risk factors for AF have been recognized, such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, heart failure (with both reduced and preserved ejection fraction), obstructive sleep apnea, aging, hyperthyroidism, and heavy alcohol use [

3]. The temporal pattern and mode of termination are the primary criteria for AF classification, including first diagnosed AF, paroxysmal AF, persistent AF, longstanding persistent AF, and permanent AF [

4]. The diagnosis of AF is based on the absence of P waves and irregular R-R interval on a 12-lead ECG [

5]. The 2020 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend that a rhythm strip not shorter than 30 seconds can also indicate AF [

4]. Contemporary AF management is based on three pillars, integrated pathways, denoted the AF Better Care (ABC) [

6]. They are symptom-directed decisions on rate versus rhythm control, optimizing stroke prevention, and managing risk factors for cardiovascular and other comorbidities.

Despite its commonness and serious health consequences, an optimal strategy for AF management remains a challenge [

7]. This is at least partly due to insufficient knowledge of the molecular mechanisms behind AF pathogenesis. Recent studies suggest the role of oxidative stress in AF pathology [

8]. The stress is associated with an overproduction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), which may damage cellular macromolecules, including nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. Oxidative DNA damage has recently been shown to be intimately linked to AF [

7,

9]. The main source of RONS is mitochondria, which generate them even in normal conditions, and mitochondrial impairment leads to RONS overproduction. Therefore, managing mitochondrial homeostasis may be an important element in AF pathophysiology, especially since mitochondria play a critical role in maintaining the electrophysiological stability and function of the heart [

10]. The involvement of impaired mitochondrial function in AF pathogenesis was confirmed in several studies (reviewed in [

11]).

Due to an important role in oxidative stress, inflammation, aging, and metabolism, mitochondrial homeostasis is important in preventing not only cardiovascular syndromes but also many other diseases [

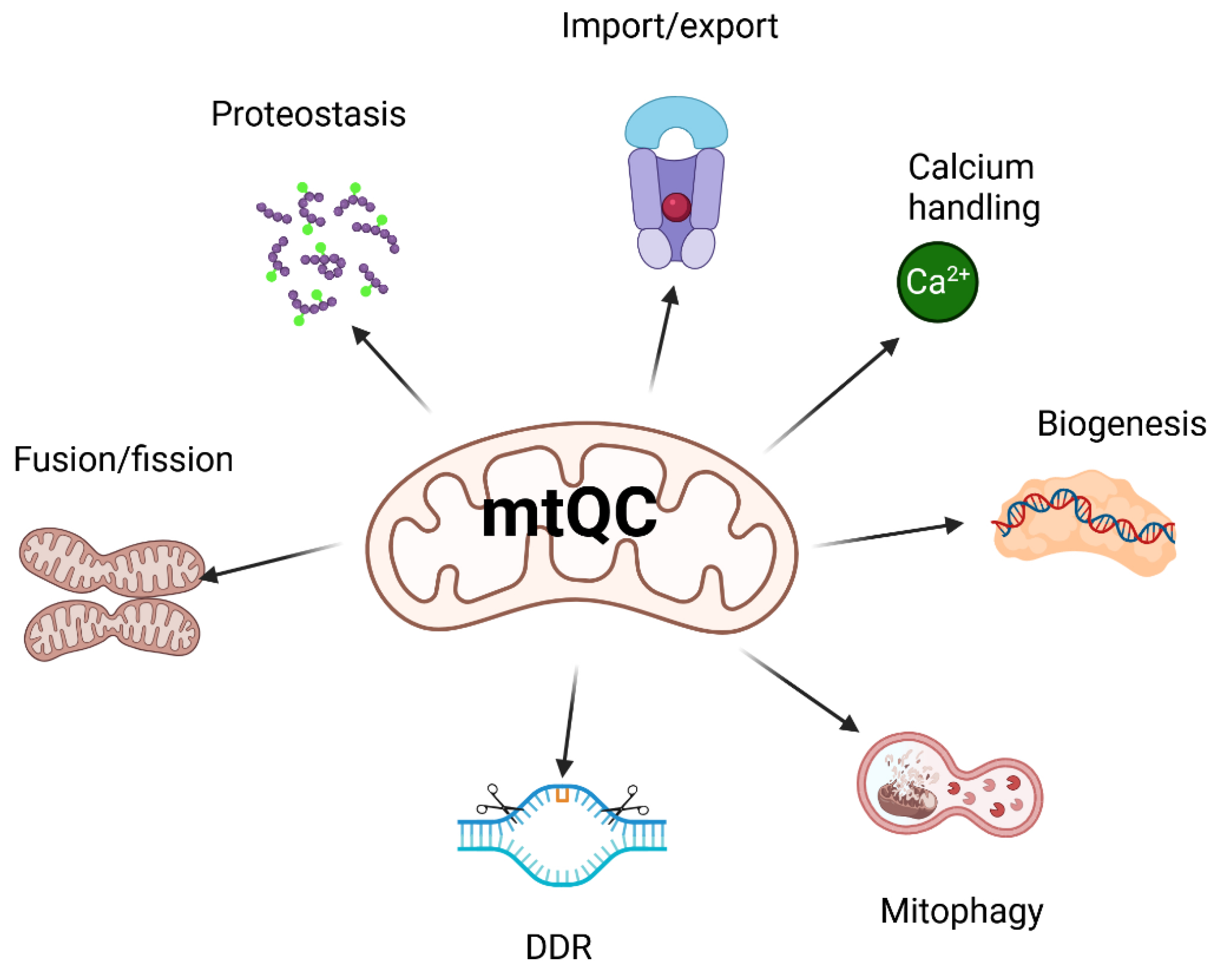

12]. Therefore, maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis is crucial for maintaining the organism’s overall homeostasis. Mitochondrial quality control (mtQC) is a set of mechanisms, including mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy and mitochondrial DNA damage response to ensure mitochondrial fitness and functions (reviewed in [

13]). All these mechanisms contain many pathways, making mtQC a complex and sophisticated organism’s reaction to keep its homeostasis.

In this narrative review, we provide information on how mitochondrial dysfunctions, expressed as disturbances in mtQC, contribute to AF through oxidative stress, calcium handling abnormalities, energy deficiency, inflammation, fibrosis, and genetic changes. In addition, we presented the protective potential of sirtuins in AF. This association of mtQC with sirtuins is justified by the antioxidant properties and mitochondrial localization of some of them. Our search strategy concentrated on mechanisms, clinical implications, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches in AF, emphasizing oxidative stress, mitochondrial homeostasis, and sirtuins. It was based on publications from PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane Library. We used search strings including “atrial fibrillation” and one of the following terms: “oxidative stress,” “ROS,” “mitochondria,” or “sirtuin.” Publications from the past decade were prioritized, unless foundational studies were necessary. The species included were humans and relevant animal models. All article types, including original research, reviews, and meta-analyses, were considered, with no language restrictions.

2. Oxidative Stress in Atrial Fibrillation

Oxidative stress is linked to many diseases, but in most cases, the causal connection between stress and a specific syndrome remains unclear. Extensive details on the role of oxidative stress in AF development have been outlined in a recent review by Pfenniger et al. [

8].

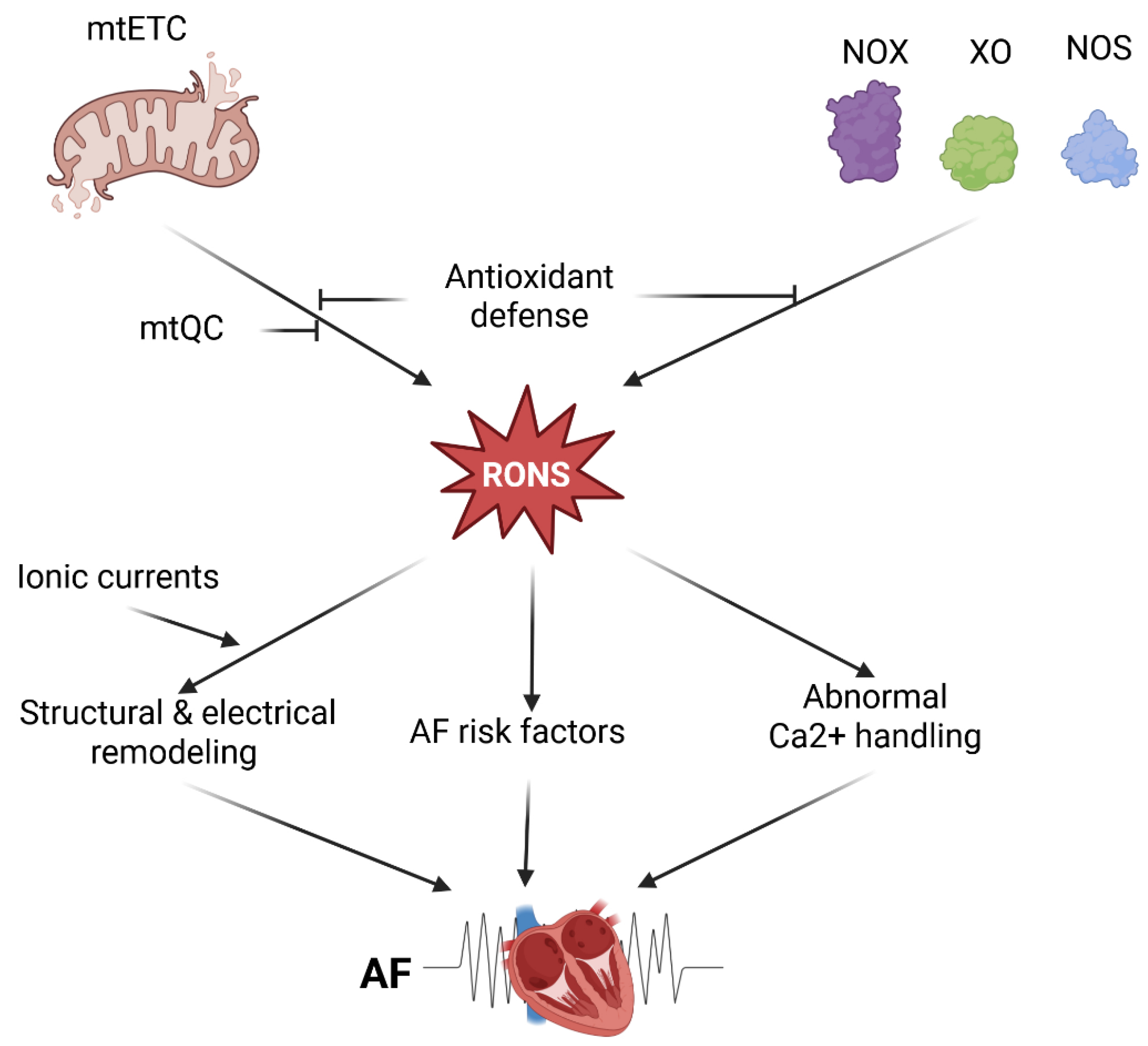

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are produced in the leaking mitochondrial electron transport chain (mtETC) and after the activation of various enzymes, including NADPH oxidases (NOX), xanthine oxidase, and uncoupled nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [

14]. Cardiomyocytes are rich in mitochondria and, therefore, may generate a high amount of RONS and may be considered the main source of RONS in the myocardium [

8]. Elevated level of RONS in the myocardium was observed in several heart syndromes, including heart infarction, heart failure, and AF [

15]. Also, NOX, xanthine oxidase, and NOS are expressed in the myocardium (reviewed in [

8]).

It should be emphasized that most data on the role of oxidative stress in AF patients are obtained indirectly, as atrial tissue can only be obtained in postoperative AF cases, not in paroxysmal or persistent AF [

16]. Using a goat model of pacing-induced AF, it was demonstrated that the upregulation of atrial NADPH oxidases is an early but temporary event in the progression of AF [

17]. Additionally, the study indicated that changes in the sources of RONS with atrial remodeling could explain why statins are effective in primary prevention of AF but not in its treatment. It was demonstrated that NOX2 was upregulated only in patients with paroxysmal/persistent AF, but not with permanent AF, and was responsible for the overproduction of isoprostanes [

18]. AF was identified early in community-acquired pneumonia and was linked to NOX2 activation [

19]. A remarkable example of the RONS-AF association was demonstrated in studies showing that atrial perfusion with hydrogen peroxide in rats induced AF [

20,

21].

Several AF risk factors, including heart failure and ischemic/nonischemic cardiomyopathy, are associated with elevated oxidative stress [

8]. The stress is induced by electron leakage from mitochondrial complexes I and III and by reduced antioxidant defense. Also, diabetes is associated with elevated RONS production due to hyperglycemia and mitochondrial dysfunction [

22]. It was demonstrated that mitochondria in atrial tissue from type 2 diabetic patients showed diminished capacity for glutamate- and fatty acid-supported respiration, in addition to increased myocardial triglyceride content [

23]. Moreover, those patients exhibited increased mitochondrial production of hydrogen peroxide during oxidation of carbohydrate- and lipid-based substrates, depleted glutathione levels, and evidence of persistent oxidative stress in their atrial tissue.

Sustained or recurrent episodes of AF can cause long-term changes in the electrical properties of the atria, known as electrical remodeling, that increase the atria’s susceptibility to arrhythmias [

24]. The key features of electrical remodeling in AF are shortening of the atrial action potential duration, changes in potassium and calcium channel function, and increased vulnerability to reentry circuits. Several ionic currents are redox-dependent in AF, as RONS produced by NOX2 and mitochondria regulate them. These include the L-type Ca

2+, inward-rectifier K

+ current, and constitutively active form of acetylcholine-dependent K

+ current (reviewed in [

8]).

Catheter ablation has emerged as a minimally invasive procedure to treat AF, particularly in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, especially those who are refractory or intolerant to antiarrhythmic drugs [

25]. Electrical remodeling contributes to the progression from paroxysmal to persistent AF and may decrease the efficacy of drug therapy and ablation in AF.

Besides electrical remodeling, structural remodeling also occurs in AF, especially during its later stages, probably due to prolonged exposure to risk factors [

26]. It involves physical and anatomical changes in the atrial tissue that occur during AF. They contribute to the persistence and worsening of arrhythmia and can make treatment more difficult. The key features of structural remodeling are atrial fibrosis, atrial dilation, myocyte degeneration and dedifferentiation, inflammation and oxidative stress, calcium overload and stretch-activated pathways. These features may impede the propagation of electrical impulses through the atria, leading to heterogeneity of electrical conduction [

27]. Fibrosis is a crucial factor in structural remodeling in AF and plays a significant role in AF treatment, especially with ablation. An involvement of NOX2 in cardiac fibrosis mediated by angiotensin II (ANGII) was shown in mice [

28]. Apart from NOX2, NOX4 may also be involved in atrial fibrosis in AF, and it has been shown that this involvement in human cardiac fibroblasts might be mediated by the transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1)-NOX4 signaling pathway [

29]. Several studies involving humans and various animal models, including serine/threonine-protein kinase STK11 (LKB1) knockout mice and mice overexpressing catalase, an enzyme that decomposes hydrogen peroxide, demonstrated the involvement of mitochondrial RONS in structural remodeling in AF [

30,

31,

32].

Paired like homeodomain 2 (PITX2) belongs to the RIEG/PITX homeobox family and acts as a transcription factor that triggers an antioxidant response to support cardiac repair [

33]. Mice deficient in the

PITX2 gene showed an increased AF susceptibility [

34]. However, the molecular mechanism underlying this effect remains debated. It has been shown that PITX1(+/-) mice exhibit longer P-wave duration, reflecting slower atrial conduction, as well as a greater inducible AF burden and persistent AF compared with wild-type mice. These issues were mitigated by 2-hydroxybenzylamine, a natural antioxidant compound [

35]. In mutant mice, RONS-related protein adducts increased in the atria, coinciding with lower levels of antioxidant gene expression. The atria of

PITX1(+/-) animals exhibited impaired mitochondrial function, characterized by disrupted mitochondrial integrity and reduced biogenesis. These issues were somewhat alleviated or avoided by 2-hydroxybenzylamine. The findings emphasize the role of lipid dicarbonyl mediators of oxidative stress in proarrhythmic remodeling and the susceptibility to AF linked to PITX2 deficiency. This suggests opportunities for creating genotype-specific treatments to prevent AF.

Increased RONS levels, originating from NOX isoforms or mitochondria, may promote AF through abnormal Ca

2+ handling in atrial myocytes, which display higher expression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2A (SERCA2A), and a lower expression of phospholamban, a SERCA2A regulator [

36,

37,

38]. Consequently, atrial myocytes display higher Ca

2+ content than their ventricular counterparts.

This strong evidence for oxidative stress’s role in AF pathogenesis supports the use of antioxidant therapies to prevent and treat AF. As presented by Pfenniger et al., these therapies can target RONS directly, their sources of production, and signaling pathways that promote an AF arrhythmogenic substrate [

8]. Although systematic antioxidant therapies did not yield satisfactory results, novel atrial-specific gene-based therapies demonstrated promising effects in large-animal AF models [

39,

40]. Further information on targeting oxidative stress in AF will be provided in the subsequent sections.

In summary, several molecular mechanisms may underlie oxidative stress’s role in AF pathogenesis. Enhanced RONS levels in AF originate from mitochondria-rich atrial cardiomyocytes, which may generate RONS due to impaired mtETC, activation of some oxidases, and compromised mtQC (

Figure 1). Therefore, these mechanisms can be considered in therapeutic strategies for AF.

3. Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Atrial Fibrillation

Although a significant portion of the results presented in the previous section can be directly or indirectly linked to dysfunctional mitochondria and, consequently, impaired mtQC, the focus was on oxidative stress without exploring the mechanisms underlying its effects.

As mentioned, many pathways contribute to mtQC, including a multilayered regulatory network that is essential for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and functional homeostasis (reviewed in [

41]). This system coordinates its key components: mitochondrial dynamics—fission and fusion; mitophagy— a specialized form of autophagy that selectively degrades damaged or no longer needed mitochondria; biogenesis; calcium homeostasis; proteostasis; unfolded protein response; import machinery; and DNA damage response (DDR) (

Figure 2). Some aspects of mtQC overlap; for example, mitochondrial DDR, unlike its nuclear counterpart, may trigger the degradation of mitochondria if they contain DNA damage beyond the organelle’s repair capacity [

42].

Mitochondrial quality control is essential for providing energy to the cardiovascular system (reviewed [

10]). Dysfunctional mtQC was implicated in many cardiovascular diseases, including ischemia-reperfusion, atherosclerosis, heart failure, cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, diabetic and genetic cardiomyopathies, and Kawasaki Disease. Consequently, mtQC is essential to promote cardiovascular health. Some aspects of mtQC were reported to be impaired in AF, suggesting potential avenues for AF prevention and treatment.

3.1. Mitochondria-Related Calcium Handling

Abnormal calcium (Ca

2+) handling in mitochondria plays a key role in AF pathogenesis (reviewed in [

43]). It interferes with the balance among energy generation, oxidative stress control, and intracellular signaling in atrial heart cells. In normal conditions mitochondria take up Ca

2+ during increased workload to stimulate the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, enhancing ATP production and maintaining redox balance. In AF mitochondrial Ca

2+ accumulation is decreased, especially during stress or increased workload [

44]. This leads to decreased ATP production, impaired regeneration of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH

2), essential for oxidative phosphorylation. Insufficient reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), which is involved in the antioxidant defense through several pathways, including glutathione regeneration, increases oxidative stress and disturbs anabolic reactions [

45].

Calcium transfer between mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is essential for cellular functions, particularly in excitable cells, including cardiomyocytes [

46]. The proximity between SR and mitochondria facilitates this transfer. In AF, this spatial organization is disrupted, mainly due to microtubule destabilization, resulting in inefficient Ca

2+ transfer, increased proarrhythmic Ca

2+ sparks, and changes in excitation–contraction coupling [

47]. Impaired mitochondrial Ca

2+ handling adds to spontaneous Ca

2+ release from the SR, electrical instability, and promotes reentry circuits, a hallmark of AF pathophysiology [

43,

48,

49,

50].

A recent study on AF patients’ derived material confirmed the importance of impaired atrial mitochondrial calcium handling in AF pathogenesis [

51]. The study revealed that during increased workload, mitochondrial Ca

2+ buildup was reduced in AF, linked to impaired NADH and FADH

2 regeneration. Disorganization of the SR and mitochondria, along with microtubule destabilization, was detected. These results were validated in human iPSC-derived myocytes, where nocodazole treatment displaced mitochondria and increased proarrhythmic Ca

2+ sparks, which MitoTEMPO could rescue. Ezetimibe also lessened arrhythmogenic Ca

2+ release events in AF myocytes and nocodazole-treated human iPSC-derived cardiac myocytes. A retrospective patient review found a lower AF burden among those taking ezetimibe. The authors concluded that mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was impaired in AF atrial myocytes, likely due to disrupted SR-mitochondria spatial organization caused by destabilized microtubules. Enhancing mitochondrial Ca

2+ uptake might serve as a protective strategy against arrhythmogenic events.

These findings suggest that focusing on mitochondrial Ca

2+ regulation may offer a new therapeutic strategy for AF, particularly in persistent or resistant cases [

52]. In therapeutic strategies, modulation of mitochondrial Ca

2+ transporters were considered. They were mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), sodium-calcium exchanger (NCLX), and ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) [

53,

54,

55].

Ezetimibe, a lipid-lowering drug, demonstrated promise in AF, especially when combined with statins [

56,

57]. Although a detailed mechanism underlying the observed profitable effects of ezetimibe in AF is not known, its influence on calcium homeostasis may play a role, as it increases mitochondrial Ca

2+ uptake and decreases arrhythmogenic Ca

2+ release [

58,

59].

In summary, cardiomyocytes heavily rely on calcium transfer between mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which depends on the close physical proximity of these two organelles, a connection disrupted in AF. Reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in AF might be connected to impaired regeneration of NADH and FADH2. Mitochondrial regulation of calcium homeostasis could be considered a therapeutic target in AF.

3.2. Energy Production

The three-way link between energy production, mitochondrial health, and atrial fibrillation (AF) is increasingly recognized as a crucial aspect of AF’s underlying mechanisms. As the main source of energy production is oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, much of the mechanisms leading to disturbed energy production associated with AF is described in the remaining subsections of this section.

Cardiac myocytes need large amounts of ATP for excitation–contraction coupling. The heart’s energy demand in AF is greater than in a normal heart because atrial cells in AF fire quickly and chaotically, often exceeding 300-500 impulses per minute [

60]. This causes ongoing depolarization and repolarization, significantly increasing the strain on the ion pumps, which require a substantial amount of ATP to restore the ionic gradient. Inefficient mechanical contraction in AF due to losing the atrium’s coordinated contraction causes a conflict with muscle cells and wastes energy that must still be supplied [

61].

Oxidative phosphorylation, essential for energy production in heart tissue, decreases in AF, as confirmed by multiple studies involving human atrial tissue and animal models. Proteomics and metabolomics analyses of left atrial biopsies from AF patients showed reduced levels of mitochondrial enzymes necessary for OXPHOS, such as GPD2 and components of mtEC [

62]. Gene set enrichment analysis revealed significant decreases in oxidative phosphorylation pathways and ATP biosynthesis processes in AF atria compared to controls. These alterations are associated with diminished mitochondrial energy metabolism and structural remodeling.

The inducibility of trial tachyarrhythmia, as well as interatrial conduction time and fibrosis, was higher in rats with diabetes mellitus in functional measurements of mitochondrial respiration [

62]. Diabetic rats generated higher levels of mitochondrial-RONS and showed reduced complex I-linked oxidative phosphorylation capacity. Treatment with empagliflozin, a sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, improved mitochondrial function. Consequently, diabetic rats with atrial arrhythmia produce less energy because of impaired OXPHOS and other mitochondrial dysfunctions.

Conflicting data relate atrial pacing to the risk of AF, and the impact of atrial pacing on mitochondrial function remains poorly understood [

63]. It was demonstrated that atrial pacing from cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) exceeding 50% is associated with higher levels of mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity and coupling efficiency [

64]. These results demonstrate that atrial pacing improves mitochondrial performance in PBMCs and enhances left ventricular contractile function in patients with CIEDs, supporting observations of the protective effect of atrial pacing against atrial arrhythmia.Early AF episodes can lead to temporary depletion of phosphocreatine and ATP, but with chronic AF, there is often some recovery of energy balance, indicating adaptive remodeling [

65,

66] .

As mentioned in the previous section, SR-mitochondrial calcium cycling is disrupted in AF, resulting in elevated spontaneous Ca

2+ release events and elevated levels of cytosolic Ca

2+, which must be actively transported back into SR or out of the cell [

67]. These processes also require a significant amount of ATP.

Enhanced ATP production imposes stress on mitochondria associated with RONS overproduction, which are produced even in normal conditions. These RONS damage the mitochondrial membranes and proteins and impair the functioning of mtETC, resulting in further RONS production (“vicious cycle”).

In summary, high ATP turnover in AF leads to effects that exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunctions, resulting in energy deficits in the atrial tissue cardiomyocytes and are serious challenges for mtQC.

3.3. Inflammation and Fibrosis

Mitochondrial damage can activate inflammatory pathways and promote fibrotic remodeling, both of which contribute to AF [

68]. Upon damage, mitochondria release molecules collectively referred to as mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), containing molecules that are important in inflammatory and immune responses in various diseases (reviewed [

69]). These include mtDNA, cardiolipin, and RONS. As mentioned, RONS can promote and/or enhance oxidative stress, and mtDNA can activate toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) and cyclic GMP–AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathways [

70]. cGAS detects cytosolic DNA, including mtDNA, and activates STING, which stimulates the production of type I interferons and other inflammatory cytokines. It was shown that mitochondrial damage mediated STING activation driving obesity-mediated AF in rats [

71]. However, it is not entirely clear whether the cGAS-STING pathway is a friend or foe in cardiac diseases; it may play a role in the low-grade inflammation associated with AF [

72].

Under normal conditions, cardiolipin binds to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Still, during mitochondrial damage or stress, it can translocate to the outer mitochondrial membrane and directly bind to the NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. This cytosolic pattern recognition receptor plays a central role in the innate immune system (reviewed [

73]). Its activation results in the cleavage of pro-caspase-1 into active caspase-1, which then processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active, pro-inflammatory forms. An increased activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome was observed in the atrial cardiomyocytes of patients with paroxysmal AF and chronic AF [

74,

75]. CM-specific knock-in mice expressing constitutively active NLRP3 (CM-KI mice) developed spontaneous premature atrial contractions and inducible AF, which was reduced by a specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, MCC950. These mice exhibited ectopic activity, abnormal Ca

2+ release from SR, shortened atrial effective refractory period, and atrial hypertrophy. Knocking down the NLRP3 gene suppressed AF development in CM-KI mice. Ultimately, genetic inhibition of NLRP3 prevented AF in a mouse model of spontaneous AF.

The interaction between the NLRP3 inflammasome and gut microbiota might be causal for AF [

76]. It should also be emphasized that the atrial-specific NLRP3 inflammasome is a key causal factor in the development, progression, and recurrence of AF after ablation [

77].

Because inflammation may induce mitochondrial damage through mtDNA lesions, disrupting mitochondrial dynamics and impairing mitophagy, if this inflammation results from mitochondrial damage, a feedback loop is established between mitochondria and inflammation. Again, a mitochondrial “vicious cycle” may occur in AF pathogenesis.

Atrial fibrosis is characterized by a metabolic reprogramming in atrial fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes. This metabolic dysregulation involves disturbances in fatty acid oxidation, glucose metabolism, and amino acid metabolism, which are closely connected to mitochondria [

78]. A 3D organoid model derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes was used to study mitochondrial impairment and cardiac fibrosis in AF [

79]. Rapid pacing at 3 Hz resulted in reduced peak contraction amplitude and contraction speed. Multi-omics analysis revealed mitochondrial damage, with notable alterations in succinate dehydrogenase subunits (SDHA–D) expression and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

PPARGC1A gene, which encodes PGC-1α—a crucial regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Cytosolic cytochrome-

c levels, indicating mitochondrial integrity, increased. Evidence of profibrotic signaling activation included the upregulation of the type-1 angiotensin II receptor (AGTR1), which is associated with fibrosis and remodeling of cardiac and vascular tissues, along with increased TGFB1. These changes elevated collagen-I and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), markers of myofibroblast differentiation characteristic of fibrosis. The organoids’ transcriptional profile closely resembled human atrial fibrosis signatures, confirming this model’s relevance for exploring mitochondrial-fibrotic remodeling in early atrial fibrillation.

In summary, damage to mitochondria may trigger inflammation and promote fibrotic remodeling that could contribute to AF development. The NLRP3 inflammasome might be an important mechanistic link between mitochondrial damage-related inflammation and AF. The cGAS-STING pathway, which detects mtDNA from damaged mitochondria, may also be involved in the low-grade inflammation associated with AF. However, inflammation can cause mtDNA damage, leading to a mutually reinforcing cycle (“vicious cycle”) in AF development.

3.4. Mitophagy

Mitophagy is a specialized type of macroautophagy that targets damaged mitochondria. When mitochondrial damage occurs, the inner mitochondrial membrane depolarizes, and the import of PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) into the mitochondria, along with its degradation by presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein (PARL), is suppressed. This results in increased accumulation of PINK1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane [

80]. Next, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase parkin (PARKIN) is recruited from the cytosol. PINK1 phosphorylates PARKIN, which then ubiquitinates many downstream autophagosome-related proteins and promotes the local formation of autophagosomes with microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3) and optineurin (OPTN). Mitophagy can also occur through a pathway that is unrelated to PINK1/PARKIN [

81].

Impaired mitophagy leads to the ineffective removal of damaged mitochondria, resulting in the accumulation and ongoing release of DAMPs, causing inflammation typical for AF and other heart diseases [

82]. Compromised mitophagy may also contribute to AF pathogenesis in other pathways.

An increased number and size of mitochondria were observed in atrial myocytes of AF patients [

83]. A decreased expression of LC3B II, the membrane-bound, lipidated form of LC3 associated with autophagosomes, was also noted in AF patients along with a decrease in the LC3B II/LC3B I (cytosolic, non-lipidated form of LC3) ratio, indicating decreased autophagosome formation. Altogether, these effects suggest mitophagy impairment in AF patients, which may be underscored by dysfunctions in the process of delivering mitochondria into autophagosomes.

A total of 444 differentially expressed genes in rats with AF were identified, including AF-related mitophagy ion channel genes: BCL2 associated X, apoptosis regulator (

BAX)

, catenin beta 1 (

CTNNB1)

, dihydropyrimidinase like 2 (

DPYSL2)

, epoxide hydrolase 1 (

EPHX1)

, glutamate-ammonia ligase

(GLUL)

, G protein subunit beta 2 (

GNB2)

, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (

MIF)

, MYC Proto-Oncogene, BHLH transcription factor (

MYC)

, and

TLR4 [

84]. Four hub genes—

BAX, GLUL, MIF, and

TLR4—were identified. In vivo studies revealed a disorganized myocardial cell structure, abnormal collagen fiber growth, widened interstitial spaces, the development of fibrous septa, and uneven cytoplasmic staining. In summary,

BAX, MIF, and

TLR4 are crucial genes linking mitophagy and ion channels in AF, likely impacting the immune microenvironment through modulation of immune cell infiltration.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MAPK14, p38αMAPK)) is a type of osmotic protein kinase that is stimulated by various forms of cellular stress [

85]. It can change the mitochondrial membrane potential, RONS, and Ca

2+ homeostasis. Studies on rats and HL-1 cells treated with angiotensin II (ANG II), a profibrogenic factor, revealed the importance of mitophagy in AF [

86]. The rat model showed that inhibition of MAPK14 downregulated the AIF Family Member 2 (

AIFM2) gene encoding an oxidoreductase that contributes to mitochondrial-related apoptosis [

87]. This effect was associated with an improvement in electrical atrial conduction. Both AF models, in vivo and in vitro, demonstrated that the MAPK14/AIFM2 pathway enhanced ANG II-induced AF by regulating mitophagy-related apoptosis. These results can be generalized, assuming that mitochondrial RONS can induce MAPK14 and AIFM2, resulting in mitophagy and apoptosis, which, in turn, lead to atrial structural remodeling, ultimately resulting in AF. Therefore, inhibition of the MAPK14/AIFM pathway may ameliorate AF induced by ANG II by regulation of mitophagy-related apoptosis.

As mentioned in the previous sections, catheter ablation is an emerging strategy for AF treatment. However, in several cases, AF recurrence is observed. The mechanism(s) behind such effects are not completely clear, but it is hypothesized that very late-onset (> 1 year) AF recurrence is underlined by a different mechanism than AF relapse during the first year after ablation [

88]. A serum PARKIN level below the median was independently associated with very late-onset AF recurrence, but not within the first year after the treatment [

89]. In contrast, ATG5, a marker of bulk autophagy, was not associated with AF recurrence. Therefore, impaired mitochondrial autophagy could play a role in the development of long-term AF recurrence.

In summary, mitophagy is emerging as a key mediator in the development and progression of AF, as impaired mitophagy fails to remove damaged mitochondria, leading to the accumulation and release of DAMPs that cause inflammation typical of AF. Impairment in mitophagy in AF is often linked to defective autophagosome formation. Many differentially expressed genes were identified in a rat model of AF. Additionally, mitophagy-related apoptosis may contribute to AF. It is worth noting that impaired mitophagy may also play a role in AF recurrence after ablation and could serve as an important prognostic marker in this critical procedure.

4. Sirtuins in Atrial Fibrillation

Sirtuins (silent information regulators, SIRTs) are an important element of epigenetic regulation of gene expression, as they are class III NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases. Humans have 7 SIRTs (SIRT1-7) localized in various cellular components, including the nucleolus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria [

90]. Emerging evidence shows an important role of sirtuins in the development of various syndromes, including cardiovascular disease [

91]. Various mechanisms can underline both the physiological and pathological functions of SIRTs beyond their regulation of gene expression. These include antioxidant and redox signaling, energy metabolism, DNA repair, and mtQC, including mitophagy [

92,

93,

94]. Therefore, SIRTs display activities that can be important in oxidative stress-related AF pathogenesis. However, the antioxidant properties of SIRTs should not be overgeneralized, as SIRT4 overexpression was recently found to accelerate heart failure development under pressure overload, primarily by enhancing profibrotic transcriptional signaling through RONS-driven mechanisms [

95].

In their primary function in mitochondria, SIRTs, mainly SIRT3, but also SIRT4 and SIRT5 to some extent, remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on mitochondrial proteins [

96]. SIRT3 deacetylates and activates enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and the TCA cycle. These include (1) subunits of complex I and II in the mtETC, which enhance mtETC efficiency; (2) components of ATP synthase, leading to increased ATP production; and (3) isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, which optimize substrate oxidation [

97,

98]. Therefore, when SIRTs are active, they increase mtETC flux, strengthen the proton gradient, and enhance ATP synthases, responding to higher ATP production during energy-demanding conditions in AF.

As mentioned, PGC-1α is a crucial protein to regulate mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism and several studies showed the involvement of sirtuins, in particular SIRT1, in its control [

99]. Fenofibrate is a PPAR-α agonist and SIRT1 regulator and it was shown that it rescued lipotoxic cardiomyopathy [

100]. Using left atria derived from AF patients, a rabbit model of AF, and HL1 cells, it was demonstrated that fenofibrate inhibited atrial metabolic remodeling in AF through the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α)/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway [

101]. A subsequent study, using the same models as the earlier work and employing honokiol, a SIRT3 agonist, showed that SIRT3 was downregulated in AF patients and the rabbit/HL1 cell model [

102]. This led to abnormal expression of its downstream metabolic key factors, which were restored by honokiol. Therefore, these two studies demonstrate that SIRT1 and SIRT3 may play a role in AF development by their involvement in atrial metabolic remodeling.

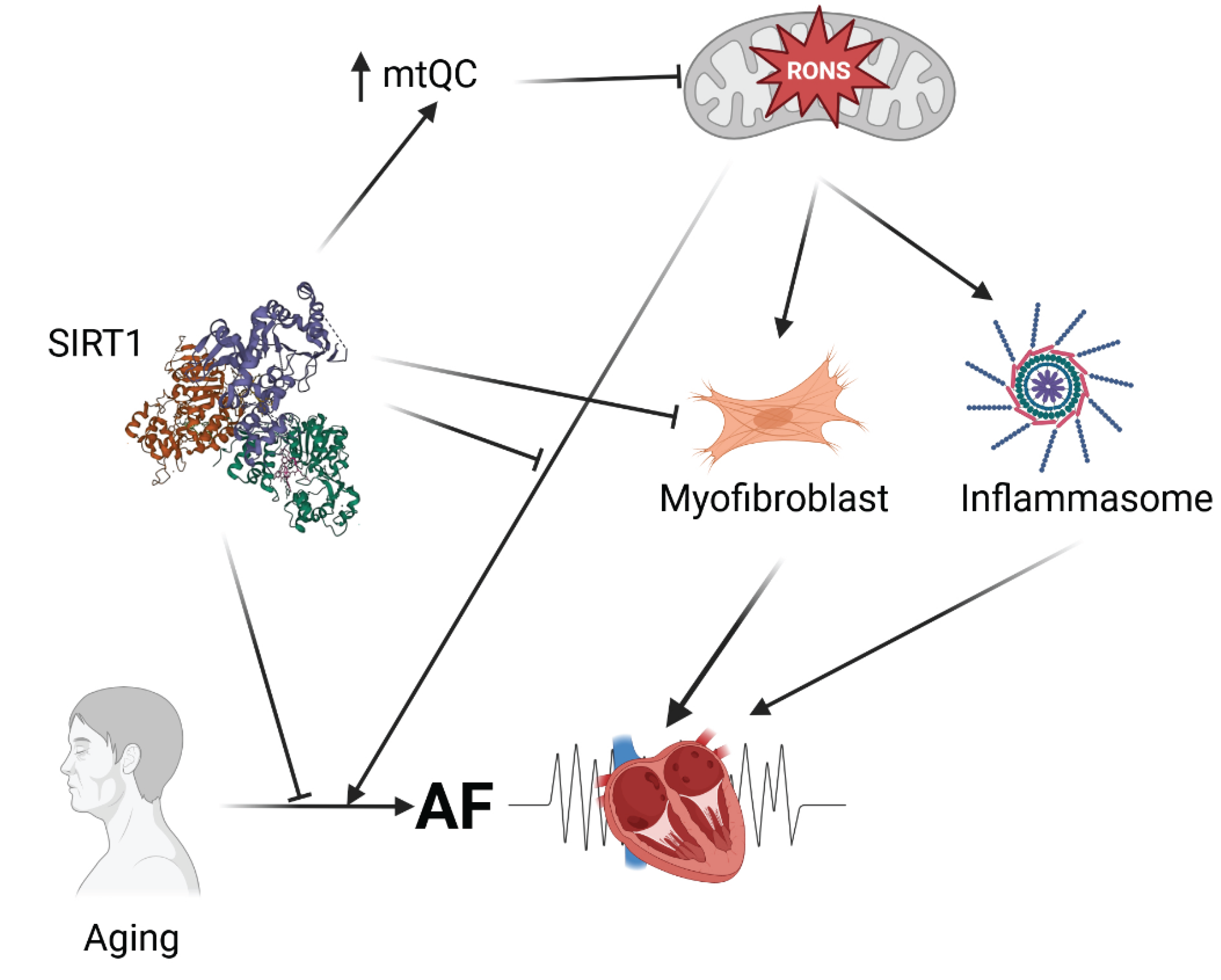

As mentioned, atrial fibrosis is a key factor in the development of AF. The fibrogenic processes in the atrium are regulated by several factors, including the transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1)-SMAD pathway. [

103]. A reduced expression of SIRT1 was observed in the right atrial appendage tissues of AF patients with a concomitant increase in the degree of fibrosis [

104]. In atrial fibroblasts, activating SIRT1 can inhibit the expression of the TGFB1-SMAD pathway and decrease fibrosis development, while inhibiting SIRT1 reduces its suppressive effect on that pathway. Therefore, SIRT1 may prevent atrial fibrosis by downregulating the TGFB1-SMAD pathway, and this mechanism can be considered in the AF prevention and treatment.

Aging is a risk factor for the onset of AF, and SIRTs expression declines with age (reviewed in [

105,

106]). To investigate the role of SIRTs in age-related AF and identify the underlying molecular mechanisms, levels of SIRT1-7 in the atria of individuals divided into age groups and aging rats [

107]. The mRNA levels of SIRT1 and SIRT5 were lower in the atria of elderly patients than in those of their younger counterparts; however, the protein levels of SIRT1 decreased, while those of SIRT5 remained unchanged. To confirm the role of SIRT1 in age-related AF, mice were genetically engineered to specifically knock out SIRT1 in the atria and right ventricle, resulting in increased atrial diameter and greater susceptibility to AF. SIRT1 deficiency activated atrial necroptosis by increasing acetylation of receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 1 (RIPK1) and subsequent phosphorylation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL). Furthermore, necrostatin-1, a necroptosis inhibitor, reduced atrial necroptosis, decreased atrial diameter, and lessened AF susceptibility in SIRT1-deficient mice. Resveratrol prevented age-related AF in rats by activating atrial SIRT and inhibiting necroptosis. Therefore, SIRT1 helps counteract age-related AF by suppressing atrial necroptosis through regulation of RIPK1 acetylation, and therefore, activating SIRT1 or inhibiting necroptosis could serve as potential therapeutic strategies for age-related AF.

Apart from aging, diabetes is a considerable risk factor for AF (reviewed in [

108]). Inhibitors of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2), an important player in diabetes pathogenesis, were reported to be helpful in treating heart failure and reducing AF risk (reviewed in [

109,

110]. SGLT2i were shown to interact with SIRTs in various pathologies, including AF, mainly in antioxidative effects [

111,

112,

113,

114]. Dapagliflozin, a SGLT2 inhibitor and sirtinol, a SIRT1 inhibitor, were used to investigate the role of the SGLT2-SIRT1 pathway in AF in a streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes mellitus [

111]. In addition, HL-1 cardiomyocytes were cultured under high-glucose (HG) conditions and treated with dapagliflozin, either in the presence or absence of sirtinol. In the rat model, dapagliflozin improved atrial fibrosis and reduced AF inducibility and duration-effects that were partially reversed by sirtinol. Therefore, dapagliflozin may alleviate cardiac fibrosis and atrial arrhythmia by modulating SIRT1. In HL-1 cells, dapagliflozin reduced apoptosis, restored autophagy and mitophagy, and enhanced calcium channel activity; however, these beneficial effects were reversed by sirtinol. Therefore, SIRT1 plays a protective role in diabetic cardiomyopathy and AF by reducing apoptosis, regulating autophagy and mitophagy, and modulating calcium channel activity.

The cGAS-STING pathway plays a key role in AF pathogenesis by detecting DNA damage, including in mitochondria, and activating genes that encode proteins involved in fibrosis and inflammation [

115]. The activity of SIRTs, in particular SIRT2, SIRT3, and SIRTT4, was demonstrated to negatively regulate the cGAS-STING pathway [

116,

117,

118]. Therefore, SIRTs are justified for further study in AF due to their involvement in the cGAS-STING pathway.

Aging is a main risk factor for AF due to cardiovascular aging and an age-related increase of comorbidity [

119]. On the other hand, SIRTs are considered to have anti-aging potential [

120]. Moreover, although the mitochondrial theory of aging is no longer the paradigm of aging, mitochondrial dysfunction remains central to the aging process [

12].

In summary, SIRTs, beyond their basic deacetylase activity, also exhibit antioxidant properties that predispose them to influence oxidative stress-related mechanisms in AF development (

Figure 3). This action of SIRTs is closely linked to mitochondrial health, especially since SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are located within mitochondria and function there. Generally, SIRTs, particularly SIRT1, have shown potential to improve AF outcomes in studies involving both AF patients and animal models. The primary aspects of AF pathogenesis that SIRTs may influence include metabolic atrial remodeling, atrial fibrosis, age-related changes in necroptosis in the atrium, macroautophagy, and mitophagy, all of which are related to mitochondrial health and aging. However, a report suggests a RONS-driven mechanism of heart failure development, mediated by SIRT4, though that study requires further validation.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Atrial fibrillation is a common cardiac arrhythmia that can have serious health consequences, including stroke, heart failure, heart attack, pulmonary emboli, cognitive impairment, and dementia. It is treatable but generally considered incurable. Oxidative stress may be involved in AF development, similar to many other syndromes. A key question is whether there are specific aspects of oxidative stress in AF. Increased RONS production in AF is mainly due to damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria, supported by the high number of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes. Experimental studies show that RONS mediate AF induction. Several AF risk factors, such as heart failure and ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy, are linked to RONS overproduction.

The main structural and functional changes in the myocardium during AF are structural and electrical remodeling, both of which are affected by mitochondrial RONS. Therefore, maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis through mtQC is essential to prevent AF, and impairments in this process may be a key element in AF development, making it a potential therapeutic target. Critical components of mtQC that can be impaired in AF include mitochondria-related calcium handling, energy production, mitochondria-related inflammation and fibrosis, and mitophagy. Numerous proteins and signaling pathways might contribute to these effects in AF, such as mitochondrial calcium transporters (MCU, NCLX, and RyR2), mitochondrial enzymes involved in OXPHOS, the cGAS-STING and MAPK14-AIFM2 pathways, NLRP3 inflammasome, PGC-1α, AGTR1, TGFB1, SDHA-D, BAX, GLUL, MIF, TLR4 genes, and PARKIN. Additional research is needed to clarify how these proteins and signaling pathways relate to one another and to the clinical presentation of AF. Moreover, further studies are required to explore how these factors interact, as mtQC involves an integrated set of cellular reactions responding to disturbances in mitochondrial homeostasis.

Sirtuins are notable in molecular pathology not only for their role as histone deacetylases but also due to their antioxidant properties. Additionally, three sirtuins function within mitochondria, and all are highly expressed in heart tissue, positioning them as natural candidates for linking oxidative stress and mitochondrial health in heart diseases.

Most research on sirtuins in human syndromes centers on SIRT1 and SIRT2. As noted, similar effects related to AF have been observed with different SIRTs, such as SIRT1 and SIRT3 in studies on atrial metabolic remodeling. This suggests that effects induced by a single SIRT may be mirrored by others. It is also important to recognize that correlations between observed effects and mRNA expression of sirtuin genes may not directly reflect the relationship at the protein level, as demonstrated by studies of SIRT1 and SIRT5 in age-related AF.

Current research indicates that some SIRTs, notably SIRT1, have beneficial effects in AF pathogenesis, primarily through their antioxidant actions. However, since SIRTs mainly act through deacetylation, it is necessary to investigate their influence on the expression of genes involved in AF, including PITX2, BAX, GLUL, MIF, and TLR4. This investigation could form part of a broader exploration of epigenetic regulation in AF development.

A negative regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway by SIRTs, justifies further studies on SIRTs in AF pathogenesis, as the pathway may activate genes whose products are involved in fibrosis and inflammation

A crucial question remains whether oxidative stress is a cause or a consequence of mitochondrial impairment, and whether it plays a role in AF pathogenesis. This is a complex issue, as oxidative stress can impair mitochondrial function, which in turn may increase RONS production and further aggravate oxidative damage.

In conclusion, disruptions in mitochondrial homeostasis may contribute to AF through multiple pathways, and sirtuins could help mitigate these disturbances. Therefore, they should be considered as part of a strategic approach to therapy for atrial fibrillation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., J.D. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., M.D., and E.P.; writing—review and editing, J.K. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Noubiap Jean, J.; Tang Janet, J.; Teraoka Justin, T.; Dewland Thomas, A.; Marcus Gregory, M. Minimum National Prevalence of Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation Inferred From California Acute Care Facilities. JACC 2024, 84, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, S.; Chiara Corti, M.; Bilato, C. Atrial Fibrillation Associated with Heart Failure, Stroke and Mortality. J Atr Fibrillation 2012, 5, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, U.; Verheule, S.; Kirchhof, P.; Goette, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiological reviews 2011, 91, 265–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, C.; Li, C.; Wang, L. Accurate detection of atrial fibrillation events with R-R intervals from ECG signals. PloS one 2022, 17, e0271596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H. The ABC pathway: an integrated approach to improve AF management. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2017, 14, 627–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.; van Wijk, S.W.; van Schie, M.S.; Taverne, Y.; de Groot, N.M.S.; Brundel, B. Quantifying DNA Lesions and Circulating Free DNA: Diagnostic Marker for Electropathology and Clinical Stage of AF. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2025, 11, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfenniger, A.; Yoo, S.; Arora, R. Oxidative stress and atrial fibrillation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2024, 196, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Zeller, T. DNA Damage in Atrial Fibrillation. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2025, 11, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atici, A.E.; Crother, T.R.; Noval Rivas, M. Mitochondrial quality control in health and cardiovascular diseases. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2023, 11, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.B.; Rhee, J.-W.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cardiac Arrhythmias. Cells 2023, 12, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: from mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Fu, X.; Li, Q. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Health and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, e70319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Di Lisa, F.; Oelze, M.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Steven, S.; Schulz, E.; Münzel, T. Crosstalk of mitochondria with NADPH oxidase via reactive oxygen and nitrogen species signalling and its role for vascular function. British journal of pharmacology 2017, 174, 1670–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moris, D.; Spartalis, M.; Spartalis, E.; Karachaliou, G.S.; Karaolanis, G.I.; Tsourouflis, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Tzatzaki, E.; Theocharis, S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the clinical significance of myocardial redox. Ann Transl Med 2017, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georghiou, G.P.; Georghiou, P.; Georgiou, A.; Triposkiadis, F. Cardiac Surgery and Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation: The Role of Cancer. Medicina 2025, 61, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, S.N.; Jayaram, R.; Nahar, K.; Antoniades, C.; Verheule, S.; Channon, K.M.; Alp, N.J.; Schotten, U.; Casadei, B. Atrial sources of reactive oxygen species vary with the duration and substrate of atrial fibrillation: implications for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Circulation 2011, 124, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cangemi, R.; Celestini, A.; Calvieri, C.; Carnevale, R.; Pastori, D.; Nocella, C.; Vicario, T.; Pignatelli, P.; Violi, F. Different behaviour of NOX2 activation in patients with paroxysmal/persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation. Heart 2012, 98, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Carnevale, R.; Calvieri, C.; Nocella, C.; Falcone, M.; Farcomeni, A.; Taliani, G.; Cangemi, R. Nox2 up-regulation is associated with an enhanced risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with pneumonia. Thorax 2015, 70, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, N.; Hayashi, H.; Kawase, A.; Lin, S.F.; Li, H.; Weiss, J.N.; Chen, P.S.; Karagueuzian, H.S. Spontaneous atrial fibrillation initiated by triggered activity near the pulmonary veins in aged rats subjected to glycolytic inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, H639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezhouman, A.; Cao, H.; Fishbein, M.C.; Belardinelli, L.; Weiss, J.N.; Karagueuzian, H.S. Atrial Fibrillation Initiated by Early Afterdepolarization-Mediated Triggered Activity during Acute Oxidative Stress: Efficacy of Late Sodium Current Blockade. J Heart Health 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturano, A.; D’Angelo, M.; Mormone, A.; Russo, V.; Mollica, M.P.; Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Rinaldi, L.; Vetrano, E.; Marfella, R.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Type 2 Diabetes: Impacts from Pathogenesis to Lifestyle Modifications. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 6651–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.J.; Kypson, A.P.; Rodriguez, E.; Anderson, C.A.; Lehr, E.J.; Neufer, P.D. Substrate-specific derangements in mitochondrial metabolism and redox balance in the atrium of the type 2 diabetic human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009, 54, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, A.; Honeycutt, C.; Langberg, J.J. Electrical Remodeling in Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 1996, 94, 2968–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameswaran, R.; Al-Kaisey, A.M.; Kalman, J.M. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: current indications and evolving technologies. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2021, 18, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, H.J.; Bohne, L.J.; Gillis, A.M.; Rose, R.A. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation in acquired forms of cardiovascular disease. Heart Rhythm O2 2020, 1, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.H.; Kuo, C.T.; Chan, T.H.; Chang, G.J.; Qi, X.Y.; Tsai, F.; Nattel, S.; Chen, W.J. Transforming growth factor-β and oxidative stress mediate tachycardia-induced cellular remodelling in cultured atrial-derived myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2011, 91, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, S.; Cave, A.C.; Narayanapanicker, A.; Grieve, D.J.; Shah, A.M. Aldosterone mediates angiotensin II-induced interstitial cardiac fibrosis via a Nox2-containing NADPH oxidase. Faseb j 2006, 20, 1546–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucoranu, I.; Clempus, R.; Dikalova, A.; Phelan, P.J.; Ariyan, S.; Dikalov, S.; Sorescu, D. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res 2005, 97, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.F.; Johnson, S.C.; Villarin, J.J.; Chin, M.T.; Nieves-Cintrón, M.; Chen, T.; Marcinek, D.J.; Dorn, G.W., 2nd; Kang, Y.J.; Prolla, T.A.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and Galphaq overexpression-induced heart failure. Circ Res 2011, 108, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsurkar, M.M.; Lahiri, S.K.; Moore, O.; Moreira, L.M.; Abu-Taha, I.; Kamler, M.; Dobrev, D.; Nattel, S.; Reilly, S.; Wehrens, X.H.T. Atrial-Specific LKB1 Knockdown Represents a Novel Mouse Model of Atrial Cardiomyopathy With Spontaneous Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2021, 144, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, C.; Li, Z.; Kim, G.; Jeevanandam, V.; Uriel, N. Molecular Mechanism of the Association Between Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure Includes Energy Metabolic Dysregulation Due to Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J Card Fail 2019, 25, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Kahr, P.C.; Morikawa, Y.; Zhang, M.; Rahmani, M.; Heallen, T.R.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Olson, E.N.; Amendt, B.A.; et al. Pitx2 promotes heart repair by activating the antioxidant response after cardiac injury. Nature 2016, 534, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Blackwell, D.J.; Yuen, S.L.; Thorpe, M.P.; Johnston, J.N.; Cornea, R.L.; Knollmann, B.C. The selective RyR2 inhibitor ent-verticilide suppresses atrial fibrillation susceptibility caused by Pitx2 deficiency. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2023, 180, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subati, T.; Kim, K.; Yang, Z.; Murphy, M.B.; Van Amburg, J.C.; Christopher, I.L.; Dougherty, O.P.; Woodall, K.K.; Smart, C.D.; Johnson, J.E.; et al. Oxidative Stress Causes Mitochondrial and Electrophysiologic Dysfunction to Promote Atrial Fibrillation in Pitx2(+/-) Mice. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2025, 18, e013199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, N.S.; Ribaric, S.; Scheuermann, M.; Mauser, U.; Paul, M.; Vetter, R. Differential lusitropic responsiveness to beta-adrenergic stimulation in rat atrial and ventricular cardiac myocytes. Pflugers Arch 2000, 441, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Mondragón, R.; Lozhkin, A.; Vendrov, A.; Runge, M.S.; Isom, L.; Madamanchi, N. NADPH Oxidases and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, A.P.; Dibb, K.M.; Trafford, A.W. Differences in intracellular calcium homeostasis between atrial and ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2009, 46, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Finet, J.E.; Wolfram, J.A.; Anderson, M.E.; Ai, X.; Donahue, J.K. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II causes atrial structural remodeling associated with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Heart Rhythm 2019, 16, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Pfenniger, A.; Hoffman, J.; Zhang, W.; Ng, J.; Burrell, A.; Johnson, D.A.; Gussak, G.; Waugh, T.; Bull, S.; et al. Attenuation of Oxidative Injury With Targeted Expression of NADPH Oxidase 2 Short Hairpin RNA Prevents Onset and Maintenance of Electrical Remodeling in the Canine Atrium: A Novel Gene Therapy Approach to Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2020, 142, 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Fu, X.; Li, Q. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Health and Disease. MedComm (2020) 2025, 6, e70319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, S.D. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its consequences for mitochondrial gene expression. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2012, 1819, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zou, Q. Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis and atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies review. Current Problems in Cardiology 2025, 50, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, F.E.; Pronto, J.R.D.; Alhussini, K.; Maack, C.; Voigt, N. Cellular and mitochondrial mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. Basic Res Cardiol 2020, 115, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koju, N.; Qin, Z.H.; Sheng, R. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate in redox balance and diseases: a friend or foe? Acta Pharmacol Sin 2022, 43, 1889–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanenko, V.; Chikando, A.; Lederer, W.J. Mitochondria in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ signaling. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2009, 41, 1957–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qi, X.; Ramos, K.S.; Lanters, E.; Keijer, J.; de Groot, N.; Brundel, B.; Zhang, D. Disruption of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Contacts Underlies Contractile Dysfunction in Experimental and Human Atrial Fibrillation: A Key Role of Mitofusin 2. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e024478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribulova, N.; Knezl, V.; Szeiff Bacova, B.; Egan Benova, T.; Viczenczová, C.; Goncalvesova, E.; Slezak, J. Disordered Myocardial Ca2+ Homeostasis Results in Substructural Alterations That May Promote Occurrence of Malignant Arrhythmias. Physiological research/Academia Scientiarum Bohemoslovaca 2016, 65, S139–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, N.; Heijman, J.; Wang, Q.; Chiang, D.; Li, N.; Karck, M.; Wehrens, X.; Nattel, S.; Dobrev, D. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Atrial Arrhythmogenesis in Patients With Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2013, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Zhou, A.; Liu, H.; Shi, G.; Liu, M.; Boheler, K.R.; Dudley, S.C., Jr. Mitochondrial Ca2+ flux modulates spontaneous electrical activity in ventricular cardiomyocytes. PloS one 2018, 13, e0200448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronto, J.R.D.; Mason, F.E.; Rog-Zielinska, E.A.; Fakuade, F.E.; Bülow, D.; Tóth, M.; Machwart, K.; Brandes, P.; Wiedmann, F.; Kohlhaas, M.; et al. Impaired Atrial Mitochondrial Calcium Handling in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, N.; Maack, C.; Pronto, J.R.D. Targeting Mitochondrial Calcium Handling to Treat Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 80, 2220–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillis, A.M.; Dobrev, D. Targeting the RyR2 to Prevent Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2022, 15, e011514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, H.; Chu, C.; Yang, J. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex: An emerging therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases (Review). International journal of molecular medicine 2025, 55, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipido, K.R.; Varro, A.; Eisner, D. Sodium calcium exchange as a target for antiarrhythmic therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2006, 159–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, C.N.; Greve, A.M.; Boman, K.; Egstrup, K.; Gohlke-Baerwolf, C.; Køber, L.; Nienaber, C.A.; Ray, S.; Rossebø, A.B.; Wachtell, K. Effect of lipid lowering on new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis: the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) study. Am Heart J 2012, 163, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.S.; Yu, T.S.; Lin, C.L. Statin versus ezetimibe-statin for incident atrial fibrillation among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with acute coronary syndrome and acute ischemic stroke. Medicine 2023, 102, e33907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sanz, C.; Ruiz-Meana, M.; Mirocasas, E.; Núñez, E.; Castellano, J.; Loureiro, M.; Barba, I.; Nozal, M.; Rodríguez-Sinovas, A.; Vázquez, J.; et al. Defective sarcoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria calcium exchange in aged mouse myocardium. Cell death & disease 2014, 5, e1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Feng, M.; Schweitzer, M.K.; Wilting, F.; Gutenthaler, S.M.; Arduino, D.M.; Fischbach, S.; Dreizehnter, L.; Moretti, A.; Gudermann, T.; et al. Approved drugs ezetimibe and disulfiram enhance mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake and suppress cardiac arrhythmogenesis. British journal of pharmacology 2021, 178, 4518–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 109–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.-M.; Dzeja, P.; Shen, W.; Jahangir, A.; Hart, C.; Terzic, A.; Redfield, M. Failing atrial myocardium: Energetic deficits accompany structural remodeling and electrical instability. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2003, 284, H1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Yokota, T.; Tsuda, M.; Handa, H.; Koya, J.; Nishino, K.; Tatsuta, D.; Natsui, H.; Kadosaka, T.; et al. Empagliflozin suppresses mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and mitigates the inducibility of atrial fibrillation in diabetic rats. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1005408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronborg, M.B.; Frausing, M.; Malczynski, J.; Riahi, S.; Haarbo, J.; Holm, K.F.; Larroudé, C.E.; Albertsen, A.E.; Svendstrup, L.; Hintze, U.; et al. Atrial pacing minimization in sinus node dysfunction and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 4246–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, T.; Gumrai, P.; Apaijai, N.; Phrommintikul, A.; Prasertwitayakij, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N.; Wongcharoen, W. Atrial pacing improves mitochondrial function in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2024, 327, H1146–h1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausma, J.; Coumans, W.A.; Duimel, H.; Van der Vusse, G.J.; Allessie, M.A.; Borgers, M. Atrial high energy phosphate content and mitochondrial enzyme activity during chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovascular Research 2000, 47, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihm, M.J.; Yu, F.; Carnes, C.A.; Reiser, P.J.; McCarthy, P.M.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Bauer, J.A. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2001, 104, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, K.; Bölck, B.; Erdmann, E.; Schwinger, R. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase modulates cardiac contraction and relaxation. Cardiovascular research 2003, 57, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korantzopoulos, P.; Letsas, K.P.; Tse, G.; Fragakis, N.; Goudis, C.A.; Liu, T. Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review. Journal of Arrhythmia 2018, 34, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xiong, W.; Fu, L.; Yi, J.; Yang, J. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in diseases: implications for therapy. Molecular Biomedicine 2025, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Liao, W.; Hou, J.; Jiang, X.; Deng, X.; Chen, G.; Ding, C. Advances in crosstalk among innate immune pathways activated by mitochondrial DNA. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Fu, Y.; Ke, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, K.; Long, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Q. Mitochondrial damage mediates STING activation driving obesity-mediated atrial fibrillation. EP Europace 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Lee, H.K.; Yu, A.C.-H.; Kipp, M.; Kaddatz, H.; Zhan, J. The cGAS/STING Pathway: Friend or Foe in Regulating Cardiomyopathy. Cells 2025, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Cheng, F.; Yuan, W. Unraveling the cGAS/STING signaling mechanism: impact on glycerolipid metabolism and diseases. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correction to: Enhanced Cardiomyocyte NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling Promotes Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2019, 139, e889. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Veleva, T.; Scott, L.; Cao, S.; Li, L.; Chen, G.; Jeyabal, P.; Pan, X.; Alsina, K.M.; Abu-Taha, I.; et al. Enhanced Cardiomyocyte NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling Promotes Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2018, 138, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Wu, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. The relationship between atrial fibrillation and NLRP3 inflammasome: a gut microbiota perspective. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1273524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppenborg, T.; Saljic, A.; Bruns, F.; Abu-Taha, I.; Dobrev, D.; Fender, A.C. A short history of the atrial NLRP3 inflammasome and its distinct role in atrial fibrillation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2025, 202, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, Y.; Rao, L.; He, Y.; Chen, Z. Reprogramming of Mitochondrial and Cellular Energy Metabolism in Fibroblasts and Cardiomyocytes: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies in Cardiac Fibrosis. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.H.; Won, J.; Park, Y.I.; Park, S.-J.; Jeong, G.J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and fibrosis in atrial fibrillation: Molecular signaling in fast-pacing organoid models. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küng, C.; Lazarou, M.; Nguyen, T.N. Advances in mitophagy initiation mechanisms. Current opinion in cell biology 2025, 94, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamark, T.; Johansen, T. Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2021, 37, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.A.; Mentzer, R.M., Jr.; Linton, P.J. Impaired mitophagy at the heart of injury. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1573–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, W.; Zhong, G.; Jiang, Z. Impaired Mitophagy: A New Potential Mechanism of Human Chronic Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiol Res Pract 2020, 2020, 6757350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yan, X.; Ma, R.; Wu, Q.; Pan, X.; Wu, Q.; Ren, J.; Huang, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Ion channels and atrial fibrillation: mitophagy as a key mediator. Frontiers in physiology 2025, 16, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, A.; Zhe, M.; Yang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: Functions and targeted therapy in diseases. MedComm—Oncology 2023, 2, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sang, W.; Jian, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, F.; Wubulikasimu, S.; Yang, L.; Tang, B.; Li, Y. MAPK14/AIFM2 pathway regulates mitophagy-dependent apoptosis to improve atrial fibrillation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2025, 199, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, N.; Ferreira Neila, P.; Medina, M. The apoptosis-inducing factor family: Moonlighting proteins in the crosstalk between mitochondria and nuclei. IUBMB life 2020, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhard, N.; Metzner, A.; Fink, T. Late arrhythmia recurrence after atrial fibrillation ablation: incidence, mechanisms and clinical implications. Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol 2022, 33, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Kataoka, N.; Imamura, T.; Koi, T.; Kinugawa, K. The clinical impact of mitochondrial autophagy on very late-onset recurrence after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Open 2025, 5, oeaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michan, S.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. The Biochemical journal 2007, 404, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-N.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chen, X.-F.; Tang, X.; Chen, H.-Z. Roles of Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. Circulation Research 2025, 136, 524–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Sirtuins in mitophagy: key gatekeepers of mitochondrial quality. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 5877–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Costantini, S.; Colonna, G. The protein-protein interaction network of the human Sirtuin family. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2013, 1834, 1998–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Garcia-Peterson, L.M.; Mack, N.J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 28, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, N.J.; Koentges, C.; Khan, E.; Pfeil, K.; Sandulescu, R.; Bakshi, S.; Költgen, C.; Vosko, I.; Gollmer, J.; Rathner, T.; et al. Sirtuin 4 accelerates heart failure development by enhancing reactive oxygen species-mediated profibrotic transcriptional signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol Plus 2025, 12, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosp, F.; Lassowskat, I.; Santoro, V.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; Fliegner, D.; Redestig, H.; Mann, M.; Christian, S.; Hannah, M.A.; Finkemeier, I. Lysine acetylation in mitochondria: From inventory to function. Mitochondrion 2017, 33, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.L.; Guarente, L. The SirT3 divining rod points to oxidative stress. Molecular cell 2011, 42, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschey, M.D.; Shimazu, T.; Goetzman, E.; Jing, E.; Schwer, B.; Lombard, D.B.; Grueter, C.A.; Harris, C.; Biddinger, S.; Ilkayeva, O.R.; et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature 2010, 464, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C.; Guarente, L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2014, 25, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Okumura, K.; Takahashi, R.; Matsui, H.; Numaguchi, Y.; Murakami, H.; Murakami, R.; Murohara, T. Combined therapy with PPARalpha agonist and L-carnitine rescues lipotoxic cardiomyopathy due to systemic carnitine deficiency. Cardiovasc Res 2006, 70, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-z.; Hou, T.-t.; Yuan, Y.; Hang, P.-z.; Zhao, J.-j.; Sun, L.; Zhao, G.-q.; Zhao, J.; Dong, J.-m.; Wang, X.-b.; et al. Fenofibrate inhibits atrial metabolic remodelling in atrial fibrillation through PPAR-α/sirtuin 1/PGC-1α pathway. British journal of pharmacology 2016, 173, 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Z.; Xu, W.; Zang, Y.X.; Lou, Q.; Hang, P.Z.; Gao, Q.; Shi, H.; Liu, Q.Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; et al. Honokiol Inhibits Atrial Metabolic Remodeling in Atrial Fibrillation Through Sirt3 Pathway. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Sheppard, R. Fibrosis in heart disease: understanding the role of transforming growth factor-β1 in cardiomyopathy, valvular disease and arrhythmia. Immunology 2006, 118, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, H. Sirt1 Inhibits Atrial Fibrosis by Downregulating the Expression of the Transforming Growth Factor-β1/Smad Pathway. Acta Cardiol Sin 2024, 40, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, N.; Raju, R. Sirtuin regulation in aging and injury. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Molecular Basis of Disease 2015, 1852, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.F.; Hou, C.; Jia, F.; Zhong, C.H.; Xue, C.; Li, J.J. Aging-associated atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review focusing on the potential mechanisms. Aging cell 2024, 23, e14309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Y.; Han, X.; Gao, Y.; Yu, H.; Duan, Y.; Shi, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. Sirt1 Deficiency Promotes Age-Related AF Through Enhancing Atrial Necroptosis by Activation of RIPK1 Acetylation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2024, 17, e012452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Green, J.B.; Halperin, J.L.; Piccini, J.P. Atrial Fibrillation and Diabetes Mellitus: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2019, 74, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowie, M.R.; Fisher, M. SGLT2 inhibitors: mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2020, 17, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xue, G.; Zhan, G.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Xia, Y. Benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in arrhythmias. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 1011429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Lin, Y.W.; Shih, J.Y.; Chen, Z.C.; Wu, N.C.; Chang, W.T.; Liu, P.Y. Dapagliflozin and Sirtuin-1 interaction and mechanism for ameliorating atrial fibrillation in a streptozotocin-induced rodent diabetic model. Biomol Biomed 2025, 25, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Chai, Q.; Wei, J.; Qin, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Qi, J.; Guo, C.; Lu, Z. Dapagliflozin targets SGLT2/SIRT1 signaling to attenuate the osteogenic transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2024, 81, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.H.; Tsai, W.C.; Chiu, C.C.; Chi, N.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Huang, T.C.; Wu, W.T.; Lin, T.H.; Lai, W.T.; Sheu, S.H.; et al. The Beneficial Effect of the SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin in Alleviating Acute Myocardial Infarction-Induced Cardiomyocyte Injury by Increasing the Sirtuin Family SIRT1/SIRT3 and Cascade Signaling. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tai, S.; Zhang, N.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y. Dapagliflozin prevents oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction via sirtuin 1 activation. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2023, 165, 115213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nature reviews. Immunology 2021, 21, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthez, M.; Xue, B.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Mu, W.C.; Wang, C.L.; Guo, J.; Yang, F.; Ma, Y.; et al. SIRT2 suppresses aging-associated cGAS activation and protects aged mice from severe COVID-19. Cell reports 2025, 44, 115562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, E.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yue, W.; Feng, X. Inhibition of Sirt3 activates the cGAS-STING pathway to aggravate hepatocyte damage in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 128, 111474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bie, J.; Song, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; You, F.; Luo, J. SIRT2 negatively regulates the cGAS-STING pathway by deacetylating G3BP1. EMBO reports 2023, 24, e57500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmer, K.; Eckardt, L.; Breithardt, G. Predisposing factors for atrial fibrillation in the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol 2017, 14, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonkowski, M.S.; Sinclair, D.A. Slowing ageing by design: the rise of NAD+ and sirtuin-activating compounds. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2016, 17, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).