1. Introduction

Cardiac remodeling is a complex and evolving biological process that plays a central role in the onset and progression of heart failure (HF). Triggered by chronic hemodynamic stress, particularly systemic hypertension, the myocardium undergoes structural and functional modifications aimed at maintaining adequate cardiac output. These initial adaptations, including cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and extracellular matrix expansion, serve as compensatory mechanisms to stabilize ventricular performance [

1]. However, sustained pressure overload eventually converts these adaptive changes into maladaptive remodeling, characterized by increased myocardial stiffness, impaired contractility, and progressive ventricular dysfunction, ultimately leading to HF [

2,

3].

Recent studies have identified cafestol, a diterpene compound naturally present in unfiltered coffee, as a bioactive molecule with diverse pharmacological properties relevant to cardiovascular health. In addition to its well-documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, cafestol demonstrated organ-protective effects in ischemia–reperfusion models, where it mitigated renal injury by modulating oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling [

4]. Its proven bioaccessibility and metabolic stability in in vitro digestion models, further support its potential for systemic therapeutic use [

5]. Cardiovascular studies have indicated that cafestol activates the Nrf2 pathway, a central regulator of cellular defense mechanisms, thereby attenuating oxidative injury and fibrotic progression [

6,

7]. Liu et al. determined that cafestol suppressed high-glucose-induced cardiac fibrosis in diabetic rats, suggesting its relevance in both metabolic and pressure-overload conditions [

8]. Moreover, the ability of cafestol to inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production and endothelial adhesion molecule expression under mechanical strain conditions highlights its anti-inflammatory potential in vascular remodeling [

9].

Mitophagy, the selective autophagic degradation of damaged mitochondria, plays a pivotal role in maintaining cardiac homeostasis under stress conditions. In pressure overload, impaired mitophagy leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and maladaptive remodeling, ultimately exacerbating cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Studies have emphasized the therapeutic relevance of mitophagy modulation in cardiovascular disease models. For example, semaglutide was demonstrated to alleviate pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy by enhancing mitophagy and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation, thereby reducing inflammation and fibrotic progression [

10]. Similarly, α-ketoglutarate ameliorated cardiac insufficiency in pressure-overloaded mice through NAD⁺–SIRT1 signaling, promoting mitophagy and mitigating ferroptosis [

11]. Several natural compounds and pharmacological agents have also demonstrated efficacy in restoring mitochondrial quality. For example, berberine enhanced cardiac function by upregulating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in HF models [

12], and alpha-lipoic acid provided cardioprotection through ALDH2-dependent Nrf1–FUNDC1 signaling [

13]. In addition, fenofibrate preserved mitochondrial dynamics and attenuated cardiac remodeling in renovascular hypertrophy, highlighting the therapeutic value of maintaining mitochondrial integrity [

14]. Traditional formulations such as Xinyang tablet have shown promise in modulating the mitochondrial unfolded protein response and FUNDC1-dependent mitophagy, thereby improving cardiac function under pressure overload [

15]. Similarly, metformin, acting synergistically with PINK1/Mfn2 overexpression, prevented cardiac injury by enhancing mitochondrial function and autophagic flux [

16]. Dietary factors also affect mitophagy. Short-term intake of a high-fat diet activated mitophagy and protected against pressure overload–induced HF; however, the long-term intake of this diet reversed these benefits [

17]. Furthermore, resveratrol promoted mitophagy and inhibited apoptosis in uremic toxin–induced intestinal barrier dysfunction, suggesting its broader systemic implications for mitochondrial quality control [

18]. Emerging evidence also indicates the involvement of cafestol in autophagy regulation. Feng et al. demonstrated that cafestol activated LKB1/AMPK/ULK1-dependent autophagy in colon cancer models, a pathway strongly linked to mitophagy and mitochondrial quality control [

19]. Given the pivotal role of mitophagy in maintaining cardiac homeostasis under stress, these findings suggest that cafestol exerts cardioprotective effects by promoting mitochondrial turnover and limiting maladaptive remodeling. Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that cafestol acts as a multifaceted modulator of cardiac remodeling through antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and mitophagy-related mechanisms. Its favorable safety profile and metabolic accessibility further strengthen its candidacy for translational research in cardiovascular therapeutics [

20].

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the therapeutic role of cafestol in pressure overload–induced cardiac pathology by examining its effects on structural remodeling, inflammatory responses, and mitochondrial regulation. By performing integrated histological, biochemical, and molecular analyses, the study provides deeper insights into how cafestol counteracts the progression of HF through the coordinated modulation of fibrosis, inflammation, and mitophagy. These insights support further exploration of cafestol as a candidate for translational research in cardiovascular therapeutics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Cafestol was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A broad panel of primary antibodies was employed to detect proteins involved in inflammation, fibrosis, apoptosis, and cellular stress responses. These included galectin-3 (Gal-3; R&D Systems, Cat# MAB1197), a marker linked to fibrotic and inflammatory signaling in cardiac tissue; CD68 (Bioss, Cat# bs-0649R), a macrophage marker; connective tissue growth factor (CTGF; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-14939); discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-8989); alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; Abcam, Cat# ab5694); and CD44 (MCE, Cat# HY-P80062), which mediates cell adhesion and fibrotic remodeling. Additional targets included collagen I (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-59772), a key extracellular matrix component; GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 2118), used as a loading control; and apoptosis-related proteins Bcl-2, Bax, and cleaved caspase-3. Stress and autophagy markers such as GRP78, ATF4, p62, and phosphorylated/total ERK and mTOR were also assessed. Secondary detection was performed using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (BioLegend, Cat# B426166), optimized for chemiluminescent visualization. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat# 23228). Western blot signals were developed using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Histological evaluation included Sirius Red staining (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 365548) for collagen detection and Masson’s Trichrome staining (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 41116121) to assess fibrotic architecture.

2.2. Animals and Experimental Model

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication, revised 2011) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Taipei Medical University (IACUC 2022-064). Male C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks old, 23.5–27.5 g) were procured from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. To model pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, mice underwent transverse aortic constriction (TAC) or sham surgery following established protocols that reliably reproduce these pathophysiological features in vivo [

21]. Anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (80 mg/kg, 3% solution; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# T48402), ensuring sufficient depth for thoracic intervention. Following intubation, animals were mechanically ventilated at 105 breaths per minute with airway pressure maintained between 13–15 cm H₂O to stabilize respiratory function. The surgical field was sterilized, and a 5 mm incision was made at the left second or third intercostal space. Soft tissue and muscle layers were carefully separated to expose the thoracic cavity. The intercostal muscle was dissected approximately 2 mm lateral to the sternum, and the chest was gently expanded using a retractor to visualize the descending thoracic aorta. A 6-0 silk suture was looped around the aorta and tied securely to induce constriction, simulating chronic pressure overload. The needle was withdrawn, and the thoracic cavity was closed in anatomical layers. Postoperative care included thermal support and close monitoring during recovery. Sham-operated mice underwent identical procedures except for the ligation step, serving as baseline controls for comparative analysis.

2.3. Echocardiographic and Hemodynamic Assessment

To evaluate cardiac morphology and function following sham or TAC surgery, transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a Philips IE-33 imaging system equipped with a 25-MHz RMV-710 transducer [

21]. M-mode recordings at the mid-papillary level were used to quantify key parameters, including left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDd), end-systolic diameter (LVESd), and ejection fraction (LVEF), enabling precise assessment of ventricular dimensions and systolic performance under pressure overload conditions. Complementary hemodynamic measurements were obtained via in vivo cardiac catheterization. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane to maintain physiological stability during data acquisition. A microtip pressure transducer catheter was advanced through the right carotid artery into the left ventricular chamber, allowing continuous recording of intraventricular pressure and heart rate. Data were analyzed using LabChart 7 software (ADInstruments), providing high-resolution insight into cardiac function across experimental groups. This dual-modality approach—combining echocardiographic imaging with invasive pressure monitoring—offers a robust framework for characterizing structural and functional cardiac changes in murine models of pressure overload. It aligns with established methodologies for investigating ventricular remodeling and inflammatory responses in vivo.

2.4. Histological Evaluation

Cardiac tissues were subjected to a standardized histological workflow to assess structural alterations and fibrotic remodeling [

21]. Following fixation, samples were dehydrated through graded ethanol series and embedded in paraffin to preserve tissue architecture. Thin sections (approximately 5 μm) were prepared and stained with Sirius Red to visualize general histological features and with Masson’s Trichrome to delineate collagen fibers, a key indicator of myocardial fibrosis. Quantification of collagen content was performed by calculating the proportion of collagen-stained area relative to the total myocardial area, in accordance with established protocols for fibrosis assessment in cardiac tissue. Inflammatory infiltration was similarly evaluated by measuring the area occupied by immune cells, providing insight into tissue-level damage and remodeling. Stained sections were imaged using a Leica DM4000B light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), ensuring high-resolution visualization of histopathological features. Quantitative analysis was conducted using Image Pro Plus software (version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA), which enabled precise measurement of fibrotic and inflammatory regions. This dual-staining approach, combining Sirius Red and Masson’s Trichrome, offers a robust framework for evaluating myocardial injury and fibrosis, and supports interpretation of therapeutic effects targeting inflammation and extracellular matrix remodeling in cardiovascular disease models.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Cardiac tissues were harvested and immediately rinsed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to preserve protein integrity. Samples were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, including phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, to prevent enzymatic degradation and preserve post-translational modifications relevant to inflammatory and stress signaling pathways. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit, ensuring accurate quantification for consistent gel loading. Equal amounts of protein were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, which offer high binding efficiency for immunodetection. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 90 minutes to reduce nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies were diluted in TBST and incubated overnight at 4°C. The antibody panel included markers of inflammation (CD68, Galectin-3), fibrosis (CTGF, DDR2, alpha-SMA, CD44, collagen I), apoptosis (Bcl-2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3), and cellular stress and autophagy (GRP78, ATF4, p62, phosphorylated and total ERK, phosphorylated and total mTOR). GAPDH was used as a housekeeping protein for normalization. After primary incubation, membranes were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:20,000 dilution) for one hour. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate and imaged with the Fusion FX5 Spectra system (Vilber Lourmat, France), allowing sensitive detection of low-abundance targets.

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

To evaluate mitochondrial ultrastructure and mitophagic activity in the context of cardiac hypertrophy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was conducted using established protocols tailored for subcellular imaging in pressure overload models. Left ventricular tissue samples were promptly harvested and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 24 hours to preserve organelle integrity. Post-fixation was performed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, followed by sequential dehydration in graded ethanol and embedding in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (~70 nm) were prepared using an ultramicrotome and mounted on copper grids. Contrast enhancement was achieved through staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Imaging was carried out using a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN transmission electron microscope, with magnifications ranging from 5,000× to 30,000× to visualize mitochondrial morphology, autophagic structures, and cristae organization. Key indicators of mitophagy—including double-membrane autophagosomes surrounding mitochondria, swelling, cristae disruption, and vacuolar degeneration—were assessed based on criteria established in prior studies of cardiac remodeling. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), with blinded observers evaluating autophagosome frequency and the proportion of structurally compromised mitochondria. This methodology enabled high-resolution characterization of mitochondrial dynamics and provided mechanistic insight into cafestol’s role in preserving organelle quality under hypertrophic stress.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Results are expressed as mean values accompanied by standard deviation (mean ± SD). Prior to statistical testing, data distributions were assessed for normality. Group differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc multiple comparison procedures to identify significant pairwise differences. A threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance throughout the study.

3. Results

3.1. Cafestol Attenuates Cardiac and Ventricular Enlargement After Transverse Aortic Constriction–Induced Hypertrophy

Cafestol exerted a measurable effect on transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Representative heart images revealed morphological differences among the experimental groups and demonstrated a visible reduction in heart and left ventricular size after cafestol treatment (

Figure 1). Quantitative analysis results confirmed that TAC surgery significantly increased both heart and left ventricular weights. However, these increases were markedly attenuated in the cafestol-treated group, indicating a reversal of pressure overload–induced hypertrophic remodeling. The observed cardioprotective effects may be attributed to the ability of cafestol to modulate oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling, thereby limiting pathological myocardial enlargement.

3.2. Cafestol Improves Cardiac Performance in TAC-Induced Hypertrophy

Cardiac function was examined through echocardiographic imaging and ventricular morphometry in mice subjected to TAC. Cafestol administration visibly improved cardiac structure and function across the treatment groups (

Figure 2). Notably, diastolic wall strain was significantly increased in cafestol-treated mice, and left ventricular ejection fraction partially recovered in cafestol-treated mice compared with untreated TAC mice. These functional improvements indicate that cafestol may protect against pressure overload–induced dysfunction. Quantitative data (

Table 1) supported these findings: TAC-induced increases in left ventricular end-diastolic volume and end-systolic volume were markedly reduced after cafestol treatment, demonstrating its capacity to limit pathological ventricular dilation. In addition, cafestol moderated changes in left ventricular internal dimensions at systole and diastole as well as posterior wall thickness, suggesting that cafestol exerted a stabilizing effect on myocardial remodeling. Measurements of interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole and end-systole remained relatively stable across all groups (

Table 1), indicating that the structural effects of cafestol may be regionally selective.

3.3. Cafestol Mitigates Histopathological Alterations in TAC-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy

Histological examination of myocardial tissue revealed marked structural disruption in mice subjected to TAC. Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining demonstrated extensive inflammatory infiltration, necrotic foci, and disorganized myocardial architecture in the TAC group, accompanied by considerable collagen accumulation indicative of fibrotic remodeling (

Figure 3). Cafestol treatment markedly alleviated these pathological changes. Collagen deposition in the left ventricle was substantially reduced after cafestol treatment, as indicated by a lower percentage of fibrotic areas, suggesting that cafestol exerts a protective effect against fibrosis. The observed reduction in the accumulation of collagen and preservation of myocardial structure indicate the potential of cafestol to mitigate fibrotic progression in pressure overload–induced hypertrophy.

3.4. Cafestol Regulates Fibrotic and Inflammatory Signaling in TAC-Induced Cardiac Remodeling

Western blot analysis results revealed marked upregulation of fibrosis- and inflammation-related markers in response to TAC. TAC surgery significantly increased the expression of Gal-3, CD68, CTGF, DDR2, α-SMA, and collagen I—hallmarks of profibrotic and inflammatory activation (

Figure 4). Cafestol treatment significantly suppressed the expression of these proteins, indicating its ability to mitigate maladaptive remodeling processes. Notably, cafestol restored CD44 expression, which had been diminished in TAC-induced hypertrophy. Given the role of CD44 in cell adhesion and migration during tissue repair, this restoration suggests the presence of a specific mechanism through which cafestol facilitates structural recovery and limits fibrotic progression. Broader pathway analysis results (

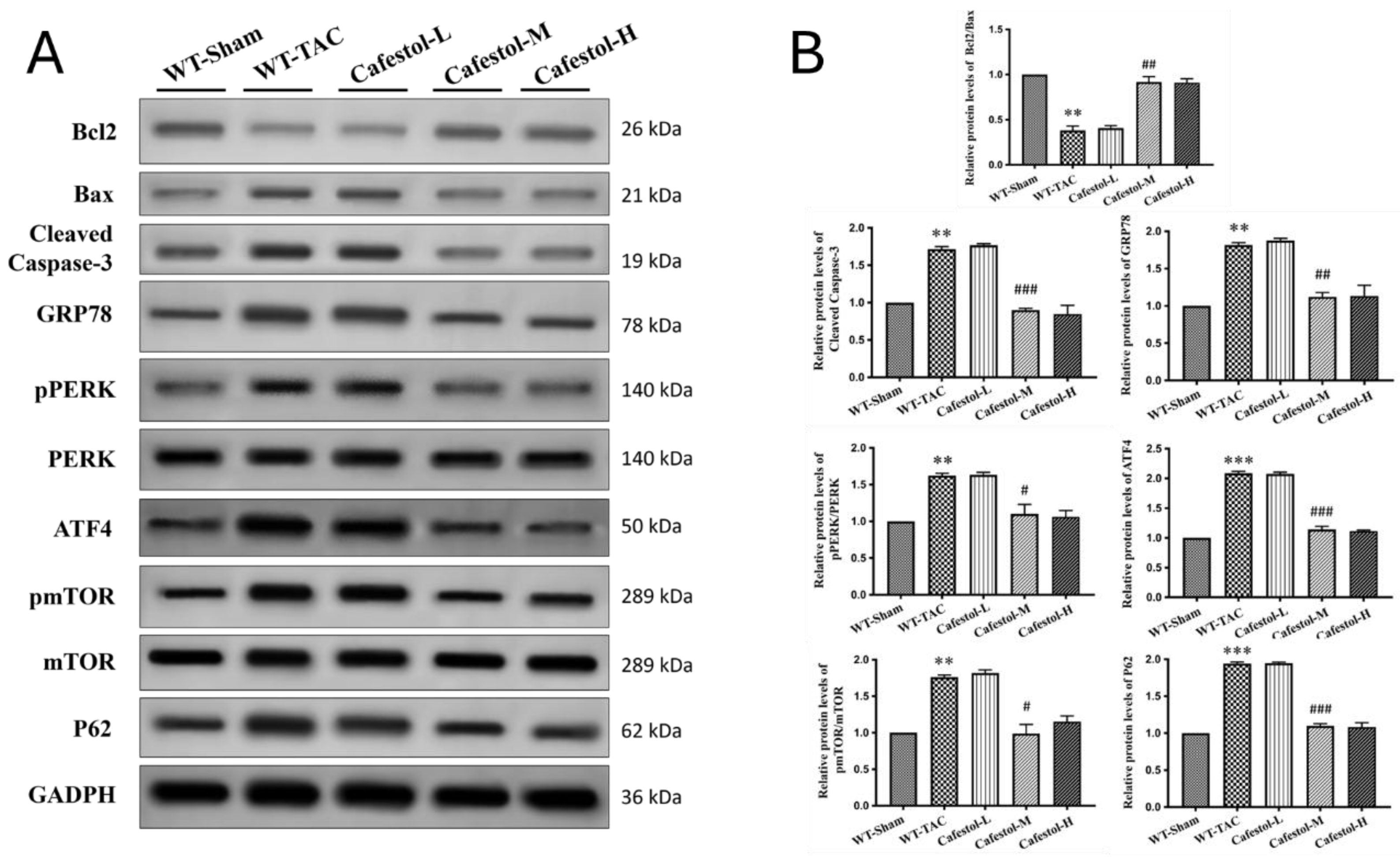

Figure 5) demonstrated that cafestol modulated key regulators of cellular stress and apoptosis. Cafestol treatment reduced the expression of proapoptotic markers, such as Bax and cleaved caspase-3, but maintained the expression of the antiapoptotic marker Bcl-2. Additionally, cafestol affected endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy-related proteins, including GRP78, ATF4, and p62, as well as the components of mTOR and ERK signaling cascades (pmTOR, mTOR, pERK, and ERK), suggesting that cafestol plays a multifaceted role in maintaining mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis. Collectively, these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of cafestol in pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy. By modulating inflammatory, fibrotic, apoptotic, and stress-responsive pathways, cafestol appears to interrupt the progression of pathological remodeling and enhance myocardial resilience.

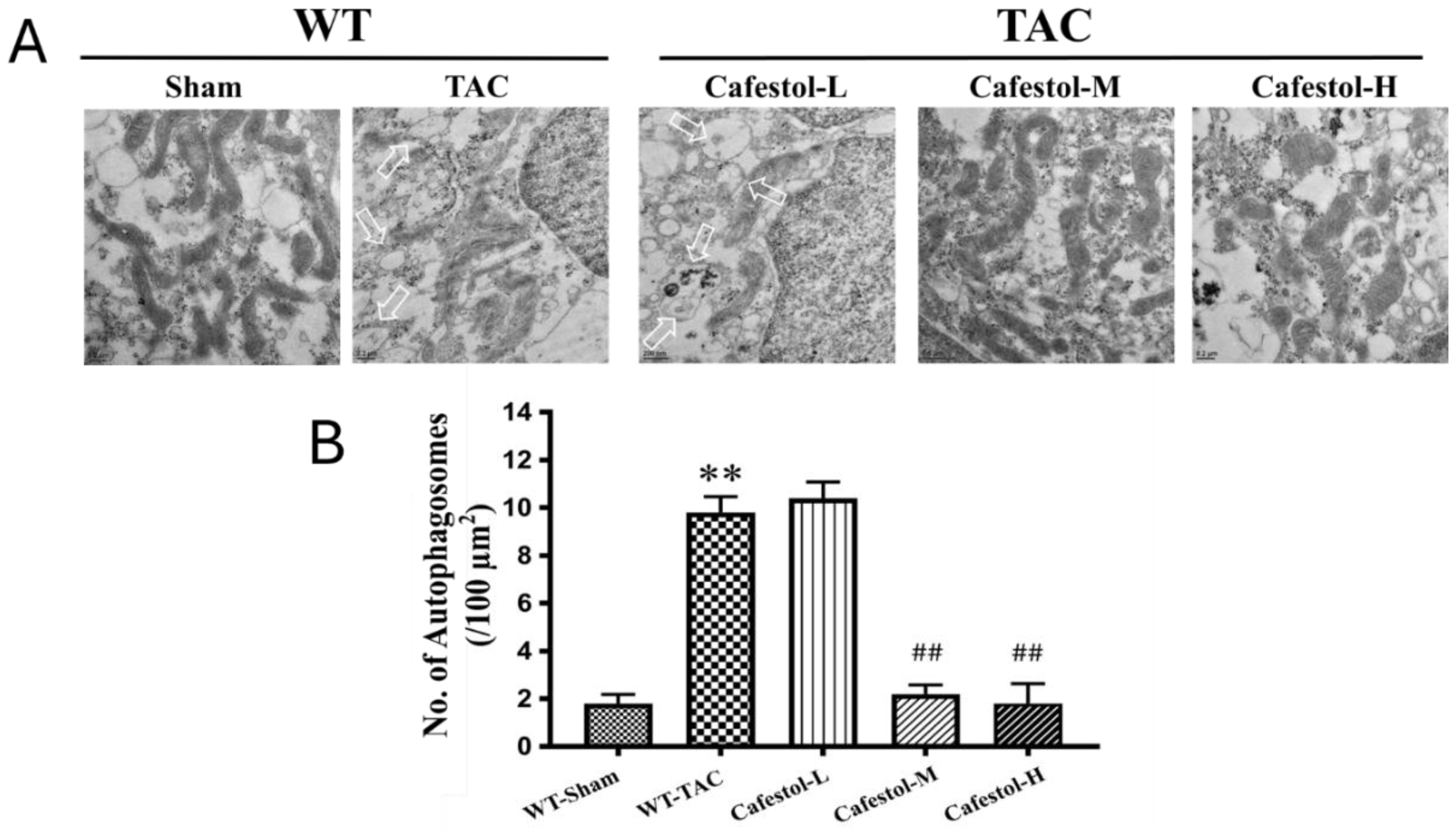

3.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy Reveals Cafestol-Mediated Mitochondrial Protection in Hypertrophic Hearts

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provided ultrastructural insights into mitochondrial remodeling in response to TAC. Myocardial tissue from TAC-operated mice exhibited pronounced mitochondrial swelling, disrupted cristae organization, and autophagosome accumulation—features indicative of impaired mitophagic clearance and increased organelle stress (

Figure 6A). These alterations reflect the substantial cellular burden imposed by pressure overload. Cafestol treatment at 10 and 50 mg/kg/day markedly improved mitochondrial morphology. TEM images revealed preserved cristae, decreased mitochondrial swelling, and fewer autophagosomes in cafestol-treated hearts, suggesting enhanced mitophagic flux and improved organelle quality control. Quantitative analysis of autophagosome density and mitochondrial integrity (

Figure 6B) corroborated these findings. Compared with the TAC control group, the cafestol-treated groups exhibited significantly lower autophagosome counts and improved mitochondrial preservation. Collectively, these results indicate that cafestol promotes mitochondrial resilience and alleviates ultrastructural damage associated with cardiac hypertrophy.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that cafestol exerted strong cardioprotective effects in a murine model of pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling. TAC resulted in marked cardiac hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, inflammatory infiltration, and apoptotic activation, consistent with maladaptive structural and molecular remodeling. Cafestol administration significantly attenuated these pathological changes, as evidenced by reduced deposition of collagen, downregulation of fibrotic markers (CTGF, DDR2, α-SMA, and collagen I), and suppression of inflammatory mediators (CD68, CD44, and galectin-3). Furthermore, cafestol attenuated apoptosis by reducing Bax and cleaved caspase-3 expression and increasing Bcl-2 levels, indicating a shift toward cell survival. Restoration of mitophagic flux and mitochondrial integrity were identified as key mechanisms underlying the therapeutic efficacy of cafestol. TAC-induced accumulation of autophagosomes and disruption of mitochondrial architecture—observed through TEM—were markedly reversed after cafestol treatment. The normalization of p62 expression, along with the preservation of mitochondrial morphology, supports enhanced autophagic clearance and organelle homeostasis. Collectively, these findings indicate that cafestol can modulate mitophagy and alleviate pressure overload–induced cardiac dysfunction through the coordinated suppression of fibrotic, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways.

4.1. Mitophagy as a Therapeutic Target

Mitophagy plays a central role in maintaining mitochondrial quality under cardiac stress, and its dysregulation has been increasingly implicated in pressure overload–induced hypertrophy and fibrosis. A recent study demonstrated that impaired mitophagic flux contributed to mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, and inflammatory activation, all of which exacerbate adverse cardiac remodeling [

22]. In the present study, TAC caused autophagosome accumulation and disrupted mitochondrial architecture, consistent with mitophagy impairment. Cafestol treatment reversed these ultrastructural abnormalities and restored p62 expression, suggesting enhanced autophagic clearance and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cafestol might regulate mitophagy through its known effects on stress-responsive signaling pathways. Previous studies demonstrated that cafestol activated the Nrf2 pathway, which strengthened antioxidant defenses and suppressed inflammasome activation and ER stress in both cardiac and hepatic models [

6,

23]. Nrf2 activation has been shown to inhibit galectin-3 secretion and reduce fibrosis in pressure overload models [

21]. Similarly, Qian Yang Yu Yin granules exerted anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome [

24]. These findings support the notion that cafestol’s modulation of mitophagy is part of a broader cytoprotective network that involves oxidative stress reduction and immune regulation. Although previous studies have primarily focused on the metabolic and anti-fibrotic effects of cafestol [

8,

25], its role in autophagy regulation has gained increasing attention. In colon cancer models, cafestol activated LKB1/AMPK/ULK1-dependent autophagy, suppressing tumor growth [

19]. Although the cardiac context differs, the involvement of similar signaling intermediates suggests a conserved mechanism through which cafestol enhances autophagic flux. Moreover, the ability of cafestol to inhibit ERK phosphorylation—a pathway linked to autophagy suppression and fibrotic signaling—supports its mitophagy-promoting potential [

23,

26]. Taken together, these findings indicate that mitophagy is a promising therapeutic target in pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling. The ability of cafestol to restore autophagic balance and preserve mitochondrial integrity complements its antifibrotic and antiapoptotic actions, offering a multifaceted basis for cardioprotection. Future studies should examine the mechanistic interactions of cafestol with the PINK1/Parkin and ULK1 pathways to fully elucidate its mitophagic profile.

4.2. Antifibrotic and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Cafestol

Cardiac fibrosis and inflammation are hallmark features of pressure overload–induced remodeling and are driven by fibroblast activation, immune cell infiltration, and extracellular matrix deposition. In the present study, cafestol markedly reduced the accumulation of interstitial collagen and suppressed the expression of fibrotic markers, including CTGF, DDR2, α-SMA, and collagen I. These effects were accompanied by the downregulation of inflammatory mediators, such as CD68, CD44, and galectin-3, indicating broad attenuation of both stromal and immune activation. A previous study demonstrated that cafestol exerted antifibrotic effects on diabetic and high-glucose models by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and reducing collagen synthesis [

8]. The ability of cafestol to suppress cyclic strain–induced inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in endothelial cells further supports its vascular anti-inflammatory activity [

9]. In pressure overload models, galectin-3 acts as a key mediator of fibrotic signaling and macrophage recruitment, and the inhibition of galectin-3 by natural compounds such as fucoidan could alleviate cardiac remodeling [

21]. The present findings suggest that cafestol exerts similar effects through the modulation of galectin-3 and associated signaling pathways. Mechanistically, cafestol’s inhibition of ERK phosphorylation may contribute to its antifibrotic efficacy because ERK signaling promotes fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix deposition [

23,

26]. Additionally, the activation of Nrf2—a transcription factor that regulates antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses—has been linked to reduced inflammasome activity and improved cardiac outcomes in hypertensive models [

6,

24]. These converging pathways regulate oxidative stress and immune cell behavior, providing a mechanistic basis for cafestol’s dual antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Taken together, these results support the notion that cafestol mitigates pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling by targeting key fibrotic and inflammatory mediators. Its effects on galectin-3, ERK, and Nrf2 pathways are consistent with previous evidence and underscore its potential as a multi-targeted therapeutic candidate in cardiovascular disease.

4.3. Apoptosis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Modulation

Apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress are strongly associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and are critical contributors to pressure overload–induced cardiac injury. In the present study, TAC increased the expression of the proapoptotic markers Bax and cleaved caspase-3 and the ER stress indicators GRP78 and ATF4, indicating maladaptive cellular stress responses. Cafestol treatment significantly reversed these alterations, suggesting that cafestol plays a protective role by preserving mitochondrial and ER homeostasis. The observed antiapoptotic activity of cafestol is consistent with previous findings in ischemia–reperfusion and diabetic models, where it upregulated Bcl-2 and suppressed caspase activation [

8,

23]. Cafestol has been suggested to reduce cellular stress and promote survival under oxidative conditions by modulating ERK signaling, a pathway that regulates both apoptosis and autophagy [

23,

26]. In hepatic and vascular systems, cafestol has also been shown to inhibit ERK-mediated inflammatory cascades, further supporting its role in stress attenuation [

9,

27]. In addition to ERK, cafestol activates the Nrf2 pathway, which enhances antioxidant defenses and alleviates ER stress by regulating molecular chaperones and unfolded protein response elements [

6,

24]. Nrf2 activation has been associated with reduced ATF4 expression and improved mitochondrial function, particularly in models of cardiotoxicity and hypertensive remodeling. These effects help preserve mitochondrial integrity and suppress apoptotic signaling, consistent with our ultrastructural observations of reduced mitochondrial disruption and autophagosome accumulation. Collectively, the ability of cafestol to modulate apoptosis and ER stress reflects its broader cytoprotective profile. By restoring the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic signaling and alleviating ER stress, cafestol contributes to the stabilization of cardiomyocyte survival under pressure overload. These mechanisms complement its mitophagy-enhancing and anti-inflammatory effects, reinforcing its therapeutic potential in cardiac remodeling.

4.4. Ultrastructural Insights from TEM

TEM facilitated direct visualization of mitochondrial morphology and autophagic structures, providing critical insight into the subcellular effects of pressure overload and cafestol intervention. In TAC hearts, we observed pronounced mitochondrial swelling, cristae disruption, and autophagosome accumulation—hallmarks of impaired mitophagic clearance and organelle stress. These features are consistent with previous reports of mitochondrial vacuolar degeneration in hypertrophic and failing myocardium [

28], and reflect a breakdown in mitochondrial quality control mechanisms. Cafestol treatment markedly preserved mitochondrial architecture, reduced autophagosome burden, and restored ultrastructural integrity. These findings are consistent with evidence from other mitophagy-enhancing interventions, such as semaglutide and α-ketoglutarate, which improved mitochondrial morphology and suppressed inflammasome activation in pressure overload models [

10,

11]. Similarly, compounds such as fenofibrate and metformin have been shown to stabilize mitochondrial dynamics and prevent fragmentation through the modulation of PINK1/Mfn2 and SIRT1 signaling [

14,

16], underscoring the therapeutic importance of mitochondrial preservation. The reduction in autophagosome accumulation observed after cafestol treatment indicates enhanced mitophagic flux instead of autophagy inhibition. This distinction is supported by studies demonstrating that mitophagy activation—rather than generalized autophagy suppression—is protective in pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling [

12,

17]. Furthermore, natural agents such as Xinyang tablets and α-lipoic acid have been demonstrated to regulate mitochondrial unfolded protein response and FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy, respectively, contributing to ultrastructural recovery and functional improvement [

13,

15]. Taken together, our TEM findings confirm that cafestol preserves mitochondrial integrity and restores autophagic balance at the ultrastructural level. These effects complement its molecular actions on p62 and apoptotic signaling, establishing mitophagy restoration as a central mechanism underlying its cardioprotective activity.

4.5. Dose-Dependent Effects and Translational Relevance

Graded administration of cafestol at 2, 10, and 50 mg/kg/day resulted in a dose-dependent attenuation of cardiac remodeling, with higher doses leading to more pronounced reductions in fibrosis, inflammation, and apoptotic signaling. This trend suggests a pharmacologically active range within which cafestol exerts cardioprotective effects, likely through the cumulative modulation of mitophagy, ER stress, and mitochondrial integrity. Similar dose-dependent benefits have been reported for other mitophagy-enhancing agents, such as semaglutide and α-ketoglutarate, which improved cardiac function and inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation in pressure overload models [

10,

11]. The translational relevance of cafestol is supported by its natural origin, oral bioavailability, and established safety profile in dietary contexts. Previous studies have demonstrated that bioactive compounds such as resveratrol and fenofibrate can modulate mitochondrial dynamics and autophagic flux in a dose-dependent manner, leading to improved cardiac outcomes in chronic disease models [

14,

18]. Moreover, interventions targeting the PINK1/Parkin and FUNDC1 pathways—such as metformin and α-lipoic acid—have shown efficacy in restoring mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing cardiac injury, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of mitophagy-based strategies [

13,

16]. The ultrastructural and molecular improvements observed with higher doses of cafestol are consistent with those reported for pharmacological agents currently under clinical investigation. These findings suggest that cafestol is a promising candidate for dietary or adjunctive therapy in pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling, although additional studies are required to define its optimal therapeutic window and long-term safety. Its ability to engage conserved mitochondrial and autophagic pathways positions it well for future translational development.

4.6. Limitations

Despite providing strong evidence for cafestol’s cardioprotective effects under pressure overload, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged to contextualize its translational relevance. First, although TEM revealed ultrastructural improvements in mitochondrial morphology and autophagosome dynamics, the study did not use genetic or pharmacological approaches to directly manipulate mitophagy-related pathways such as PINK1/Parkin and FUNDC1. Previous studies using agents such as berberine or α-lipoic acid have demonstrated that targeted modulation of these axes can clarify causal relationships between mitophagy and cardiac outcomes [

12,

13]. Without such mechanistic analyses, the specific contribution of mitophagy to cafestol’s effects remains inferential. Second, the absence of long-term follow-up limits the ability to examine sustained efficacy and safety. Although short-term interventions, such as semaglutide and α-ketoglutarate, have been reported to be beneficial in pressure overload models [

10,

11], chronic studies are necessary to evaluate potential metabolic, hepatic, or vascular consequences of prolonged cafestol exposure, particularly given its known interactions with lipid metabolism and nuclear receptors. Third, the study examined only male mice, which may not fully capture sex-specific responses to pressure overload or mitophagy modulation. A previous study reported differences in cardiac remodeling patterns and mitochondrial stress responses between sexes, suggesting that future studies should include both male and female cohorts to enhance generalizability [

29]. Finally, although the selected doses of cafestol produced a graded therapeutic effect, the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and tissue distribution of cafestol were not evaluated. These parameters are essential for translating preclinical findings into clinical applications, as observed in studies of metformin and fenofibrate, where mitochondrial targeting and systemic exposure were carefully characterized [

14,

16]. In summary, although the current findings highlight the potential of cafestol as a mitophagy-modulating agent in cardiac remodeling, additional mechanistic, pharmacological, and sex-inclusive studies are warranted to validate its clinical applicability.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that cafestol effectively mitigates pressure overload–induced cardiac remodeling through the coordinated modulation of mitophagy, suppression of fibrotic and inflammatory signaling, and preservation of mitochondrial ultrastructure. The restoration of p62 expression, reduction in autophagosome accumulation, and normalization of mitochondrial morphology collectively support enhanced mitophagic flux and organelle homeostasis. These results are consistent with emerging evidence that targeting mitochondrial quality control—particularly through PINK1/Parkin-, FUNDC1-, and SIRT1-related pathways—can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction [

11,

12,

13]. Cafestol’s dose-dependent efficacy and oral bioavailability position it as a promising candidate for translational development. Its natural origin and established safety in dietary contexts provide practical advantages over synthetic agents. However, as with other mitophagy-enhancing compounds such as semaglutide and fenofibrate, additional pharmacokinetic and mechanistic studies are required to define its therapeutic range and long-term safety [

10,

14]. The integration of mitochondrial unfolded protein response and ER stress modulation—reported with Xinyang tablets and SOCS3-targeted interventions—may offer additional insights into cafestol’s multi-pathway regulatory effects [

15,

29]. Future research should investigate molecular interactions between cafestol and key mitophagy regulators, including ULK1, Mfn2, and NAD⁺-dependent signaling pathways. Studies addressing sex-specific responses, chronic dosing, and combination therapy with established cardioprotective agents are also warranted to enhance clinical relevance. Moreover, given the growing interest in dietary strategies that improve mitochondrial health, cafestol may serve as a prototype for nutraceutical approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Crude immunoblotting data supporting mitophagy-related protein expression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-H.C. and J.-C.L.; methodology, W.-R.H.; software, C.-C.C.; validation, W.-R.H., C.-C.C. and G.-C.H.; formal analysis, G.-C.H.; investigation, J.-H.L.; resources, H.-Y.C.; data curation, J.-H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-R.H.; writing—review and editing, T.-H.C.; visualization, G.-C.H.; data interpretation, J.-J.C.; supervision, T.-H.C. and J.-C.L.; project administration, J.-C.L.; funding acquisition, J.-J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan, grant numbers NSTC 112-2314-B-038-105 and MOST 111-2314-B-039-014, and by China Medical University, Taiwan, grant number CMU111-MF-102.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Taipei Medical University (protocol code IACUC 2022-064, approved in 2022), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication, revised 2011).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TAC |

Transverse Aortic Constriction |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| ERK |

Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| mTOR |

mammalian target of Rapamycin |

| BCA |

Bicinchoninic Acid |

| PVDF |

Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| HRP |

Horseradish Peroxidase |

| ECL |

Enhanced Chemiluminescence |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

| IACUC |

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| Nrf2 |

Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| SIRT1 |

Sirtuin 1 |

| FUNDC1 |

FUN14 Domain Containing 1 |

| LVEF |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| LVEDV |

Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume |

| LVESV |

Left Ventricular End-Systolic Volume |

| SV |

Stroke Volume |

| LVIDs |

Left Ventricular Internal Dimension at Systole |

| LVIDd |

Left Ventricular Internal Dimension at Diastole |

| LVPWd |

Left Ventricular Posterior Wall Thickness at Diastole |

| IVSs |

Interventricular Septal Thickness at Systole |

| IVSd |

Interventricular Septal Thickness at Diastole |

References

- Mavrogeni, S.; Piaditis, G.; Bacopoulou, F.; Chrousos, G.P. Cardiac Remodeling in Hypertension: Clinical Impact on Brain, Heart, and Kidney Function. Horm Metab Res 2022, 54, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaydarski, L.; Petrova, K.; Stanchev, S.; Pelinkov, D.; Iliev, A.; Dimitrova, I.N.; Kirkov, V.; Landzhov, B.; Stamenov, N. Morphometric and Molecular Interplay in Hypertension-Induced Cardiac Remodeling with an Emphasis on the Potential Therapeutic Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, M.; Mi, X.; Ishii, Y.; Kato, Y.; Nishimura, A. Cardiac remodeling: novel pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J Biochem 2024, 176, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.S.; Romanelli, M.A.; Gomes, S.P.S.; Brand, A.L.M.; da Silva, R.M.V.; Oliveira, S.S.C.; Santos, A.L.S.; Rezende, C.M.; Lara, L.S. Pharmacological Potential of Cafestol, a Bioactive Substance in Coffee, in Preventing Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 22825–22836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.; Silva, A.; Andriolo, C.; Mellinger, C.; Uekane, T.; Garrett, R.; Rezende, C. Bioaccessibility of Cafestol from Coffee Brew: A Metabolic Study Employing an In Vitro Digestion Model and LC-HRMS. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 27876–27883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kenany, S.A.; Al-Shawi, N.N. Protective effect of cafestol against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1206782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belka, M.; Gostyńska-Stawna, A.; Stawny, M.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V. Activation of Nrf2 and FXR via Natural Compounds in Liver Inflammatory Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.C.; Chen, P.Y.; Hao, W.R.; Liu, Y.C.; Lyu, P.C.; Hong, H.J. Cafestol Inhibits High-Glucose-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis in Cardiac Fibroblasts and Type 1-Like Diabetic Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 4503747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, W.R.; Sung, L.C.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, P.Y.; Cheng, T.H.; Chao, H.H.; Liu, J.C.; Chen, J.J. Cafestol Inhibits Cyclic-Strain-Induced Interleukin-8, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1, and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Production in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 7861518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wei, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, R.; Jiang, Z. Semaglutide ameliorates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by improving cardiac mitophagy to suppress the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 11824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Gan, D.; Luo, Z.; Yang, Q.; An, D.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, D.; et al. α-Ketoglutarate improves cardiac insufficiency through NAD(+)-SIRT1 signaling-mediated mitophagy and ferroptosis in pressure overload-induced mice. Mol Med 2024, 30, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudureyimu, M.; Yu, W.; Cao, R.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, H. Berberine Promotes Cardiac Function by Upregulating PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy in Heart Failure. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 565751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yin, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Dong, Z.; Hu, K.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. Alpha-lipoic acid protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure via ALDH2-dependent Nrf1-FUNDC1 signaling. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, L.; Gelosa, P.; Muluhie, M.; Mercuriali, B.; Rzemieniec, J.; Gotti, M.; Fiordaliso, F.; Busca, G.; Sironi, L. Fenofibrate reduces cardiac remodeling by mitochondrial dynamics preservation in a renovascular model of cardiac hypertrophy. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 978, 176767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhuang, H.W.; Wen, R.J.; Huang, Y.S.; Liang, B.X.; Li, H.; Xian, S.X.; Li, C.; Wang, L.J.; Wang, J.Y. Xinyang tablet alleviated cardiac dysfunction in a cardiac pressure overload model by regulating the receptor-interacting serum/three-protein kinase 3/FUN14 domain containing 1-mediated mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitophagy. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 330, 118152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Xiong, W.; Zhou, H.; Yang, X.; Zeng, Q.; Ren, H.; et al. Metformin Collaborates with PINK1/Mfn2 Overexpression to Prevent Cardiac Injury by Improving Mitochondrial Function. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, G.; Lou, J.; Feng, M.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, P.; Yang, H.; Dong, L.; et al. Short-term but not long-term high fat diet feeding protects against pressure overload-induced heart failure through activation of mitophagy. Life Sci 2021, 272, 119242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.M.; Hou, Y.C.; Tsai, K.W.; Hu, W.C.; Yang, H.C.; Liao, M.T.; Lu, K.C. Resveratrol Mitigates Uremic Toxin-Induced Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease by Promoting Mitophagy and Inhibiting Apoptosis Pathways. Int J Med Sci 2024, 21, 2437–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Mi, F.; et al. Cafestol inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth in xenograft mice by activating LKB1/AMPK/ULK1-dependent autophagy. J Nutr Biochem 2024, 129, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, N.V.; Kozubek, M.; Hoenke, S.; Ludwig, S.; Deigner, H.P.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Csuk, R. Towards Cytotoxic Derivatives of Cafestol. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.R.; Cheng, C.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Cheng, T.H.; Liu, J.C.; Chen, J.J. Fucoidan Attenuates Cardiac Remodeling by Inhibiting Galectin-3 Secretion, Fibrosis, and Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Pressure Overload. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, T.; Gan, D.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, D. PINK1-mediated mitophagy attenuates pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing the mtDNA release-activated cGAS-STING pathway. Cardiovasc Res 2025, 121, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Wu, L.; Feng, J.; Mo, W.; Wu, J.; Yu, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Dai, W.; Xu, X.; et al. Cafestol preconditioning attenuates apoptosis and autophagy during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting ERK/PPARγ pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 84, 106529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Yuan, F.; Liu, M.; Fang, Z. Qian Yang Yu Yin Granule prevents hypertensive cardiac remodeling by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation via Nrf2. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 337, 118820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.R.; Sung, L.C.; Chen, C.C.; Hong, H.J.; Liu, J.C.; Chen, J.J. Cafestol Activates Nuclear Factor Erythroid-2 Related Factor 2 and Inhibits Urotensin II-Induced Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Am J Chin Med 2019, 47, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.B. Kahweol Found in Coffee Inhibits IL-2 Production Via Suppressing the Phosphorylations of ERK and c-Fos in Lymphocytic Jurkat Cells. J Diet Suppl 2021, 18, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Sung, L.C.; Haw, W.R.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, S.F.; Liu, J.C.; Cheng, T.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Loh, S.H.; Tsai, C.S. Cafestol, a coffee diterpene, inhibits urotensin II-induced interleukin-8 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 820, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaanine, A.H. Morphological Stages of Mitochondrial Vacuolar Degeneration in Phenylephrine-Stressed Cardiac Myocytes and in Animal Models and Human Heart Failure. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, W.C.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lin, Q.Y.; Liao, J.W.; Song, G.R.; Ma, X.L.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, B. SOCS3 Negatively Regulates Cardiac Hypertrophy via Targeting GRP78-Mediated ER Stress During Pressure Overload. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 629932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of cafestol on cardiac morphology and weight parameters under different experimental conditions. (A) Representative images of excised hearts from each group illustrate the morphological impact of cafestol treatment. (B) Quantitative analysis of heart weight-to-body weight ratios reveals significant increases following transverse aortic constriction (TAC), indicative of hypertrophic remodeling. Cafestol administration at varying doses (2 mg/kg/day [Cafestol L], 10 mg/kg/day [Cafestol M], and 50 mg/kg/day [Cafestol H]) mitigated these elevations compared to the untreated TAC group. Experimental groups included sham-operated controls, TAC-only mice, and TAC mice receiving cafestol at the indicated doses. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 5 per group. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham; ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC.

Figure 1.

Effects of cafestol on cardiac morphology and weight parameters under different experimental conditions. (A) Representative images of excised hearts from each group illustrate the morphological impact of cafestol treatment. (B) Quantitative analysis of heart weight-to-body weight ratios reveals significant increases following transverse aortic constriction (TAC), indicative of hypertrophic remodeling. Cafestol administration at varying doses (2 mg/kg/day [Cafestol L], 10 mg/kg/day [Cafestol M], and 50 mg/kg/day [Cafestol H]) mitigated these elevations compared to the untreated TAC group. Experimental groups included sham-operated controls, TAC-only mice, and TAC mice receiving cafestol at the indicated doses. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 5 per group. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham; ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC.

Figure 2.

Impact of cafestol on cardiac function in a murine model of TAC-induced hypertrophy. (A) Representative echocardiographic images from each group illustrate alterations in cardiac performance following transverse aortic constriction (TAC) and cafestol treatment. (B) Quantitative assessment of diastolic wall strain (DWS) reveals significant group differences. TAC surgery led to a marked reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction compared to sham-operated controls, while cafestol administration at 2 mg/kg/day (CafestolL), 10 mg/kg/day (CafestolM), and 50 mg/kg/day (CafestolH) partially restored systolic function. DWS was calculated using the formula: DWS = [PWT(systole) − PWT(diastole)] / PWT(systole), serving as an indicator of left ventricular diastolic stiffness. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham; ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC.

Figure 2.

Impact of cafestol on cardiac function in a murine model of TAC-induced hypertrophy. (A) Representative echocardiographic images from each group illustrate alterations in cardiac performance following transverse aortic constriction (TAC) and cafestol treatment. (B) Quantitative assessment of diastolic wall strain (DWS) reveals significant group differences. TAC surgery led to a marked reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction compared to sham-operated controls, while cafestol administration at 2 mg/kg/day (CafestolL), 10 mg/kg/day (CafestolM), and 50 mg/kg/day (CafestolH) partially restored systolic function. DWS was calculated using the formula: DWS = [PWT(systole) − PWT(diastole)] / PWT(systole), serving as an indicator of left ventricular diastolic stiffness. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham; ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC.

Figure 3.

Histological evaluation of cafestol’s impact on myocardial integrity and fibrosis in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative micrographs of left ventricular sections stained with Masson’s trichrome (top panels) and Sirius red (bottom panels), captured at 200× magnification. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (B, C) Quantitative assessments of myocardial injury and collagen accumulation are shown as percentage area measurements. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. ###P < 0.01 vs. TAC group.

Figure 3.

Histological evaluation of cafestol’s impact on myocardial integrity and fibrosis in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative micrographs of left ventricular sections stained with Masson’s trichrome (top panels) and Sirius red (bottom panels), captured at 200× magnification. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (B, C) Quantitative assessments of myocardial injury and collagen accumulation are shown as percentage area measurements. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. ###P < 0.01 vs. TAC group.

Figure 4.

Cafestol’s effects on fibrotic and inflammatory protein expression in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative Western blot images showing expression levels of galectin-3 (Gal-3), CD68, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen I, and CD44 across experimental groups. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Quantitative bar charts summarizing densitometric analysis of protein bands. TAC surgery elevated fibrotic and inflammatory markers, while cafestol treatment reduced their expression and restored CD44 levels. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

Figure 4.

Cafestol’s effects on fibrotic and inflammatory protein expression in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative Western blot images showing expression levels of galectin-3 (Gal-3), CD68, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen I, and CD44 across experimental groups. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Quantitative bar charts summarizing densitometric analysis of protein bands. TAC surgery elevated fibrotic and inflammatory markers, while cafestol treatment reduced their expression and restored CD44 levels. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

Figure 5.

Cafestol’s regulatory effects on apoptosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and signaling pathways in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative Western blot images showing expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3, GRP78, ATF4, p62, phosphorylated and total ERK (pERK, ERK), and phosphorylated and total mTOR (pmTOR, mTOR) across experimental groups. GAPDH served as a loading control. (B) Corresponding bar charts present densitometric quantification of protein expression. TAC surgery elevated pro-apoptotic and stress markers while suppressing protective signaling components. Cafestol treatment reversed these changes, indicating its role in modulating cell survival and stress adaptation pathways. Data are shown as mean ± SD, n = 3 per group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

Figure 5.

Cafestol’s regulatory effects on apoptosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and signaling pathways in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Representative Western blot images showing expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3, GRP78, ATF4, p62, phosphorylated and total ERK (pERK, ERK), and phosphorylated and total mTOR (pmTOR, mTOR) across experimental groups. GAPDH served as a loading control. (B) Corresponding bar charts present densitometric quantification of protein expression. TAC surgery elevated pro-apoptotic and stress markers while suppressing protective signaling components. Cafestol treatment reversed these changes, indicating its role in modulating cell survival and stress adaptation pathways. Data are shown as mean ± SD, n = 3 per group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural assessment of mitophagy and mitochondrial integrity in left ventricular myocardium following TAC and cafestol treatment. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images from sham-operated, TAC, and cafestol-treated mice (10 and 50 mg/kg/day) reveal distinct morphological changes. TAC hearts display swollen mitochondria, disrupted cristae, and elevated autophagosome formation, indicative of organelle stress and impaired mitophagic activity. White arrows denote autophagosomes. Cafestol administration restores mitochondrial architecture and reduces autophagosome density, suggesting improved mitophagic flux and structural preservation. (B) Quantitative analysis of autophagosome density and mitochondrial integrity across experimental groups. Data are shown as mean ± SD, n = 5 per group. **P < 0.01 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01 vs. TAC group.

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural assessment of mitophagy and mitochondrial integrity in left ventricular myocardium following TAC and cafestol treatment. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images from sham-operated, TAC, and cafestol-treated mice (10 and 50 mg/kg/day) reveal distinct morphological changes. TAC hearts display swollen mitochondria, disrupted cristae, and elevated autophagosome formation, indicative of organelle stress and impaired mitophagic activity. White arrows denote autophagosomes. Cafestol administration restores mitochondrial architecture and reduces autophagosome density, suggesting improved mitophagic flux and structural preservation. (B) Quantitative analysis of autophagosome density and mitochondrial integrity across experimental groups. Data are shown as mean ± SD, n = 5 per group. **P < 0.01 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01 vs. TAC group.

Table 1.

Summary of echocardiographic measurements following Cafestol administration in a murine model of TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Parameters assessed include left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), end-systolic volume (LVESV), stroke volume (SV), and diastolic mass (LVd Mass). Additional structural indices include left ventricular internal dimensions during systole (LVIDs) and diastole (LVIDd), posterior wall thickness at end-diastole (LVPWd), and interventricular septal thickness at systole (IVSs) and diastole (IVSd). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. Statistical comparisons are denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

Table 1.

Summary of echocardiographic measurements following Cafestol administration in a murine model of TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Parameters assessed include left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), end-systolic volume (LVESV), stroke volume (SV), and diastolic mass (LVd Mass). Additional structural indices include left ventricular internal dimensions during systole (LVIDs) and diastole (LVIDd), posterior wall thickness at end-diastole (LVPWd), and interventricular septal thickness at systole (IVSs) and diastole (IVSd). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with n = 5 per group. Statistical comparisons are denoted as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated controls; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. TAC group.

| |

Sham |

TAC |

Cafestol-L |

Cafestol-M |

Cafestol-H |

|

LVEDV (ml) |

0.131± 0.036 |

0.208±0.01** |

0.177±0.021# |

0.195±0.025 |

0.143±0.025### |

|

LVESV (ml) |

0.038±0.018 |

0.094±0.021** |

0.058±0.013## |

0.068±0.012# |

0.034±0.012### |

|

SV (ml) |

0.093±0.019 |

0.114±0.018 |

0.119±0.011 |

0.127±0.028 |

0.109±0.02 |

| LVd Mass |

0.112±0.031 |

0.234±0.034*** |

0.168±0.013## |

0.158±0.023## |

0.158±0.007## |

| LVIDs |

0.230±0.043 |

0.332±0.023** |

0.282±0.02## |

0.298±0.017# |

0.232±0.029### |

| LVIDd |

0.370±0.036 |

0.438±0.007** |

0.414±0.017# |

0.428±0.019 |

0.384±0.023## |

| LVPWd |

0.084±0.008 |

0.116±0.008*** |

0.100±0.000## |

0.088±0.01## |

0.100±0.000## |

| IVSs |

0.112±0.015 |

0.138±0.012* |

0.138±0.012 |

0.124±0.017 |

0.144±0.005 |

| IVSd |

0.084±0.008 |

0.12±0.0155* |

0.100±0.000# |

0.096±0.01# |

0.106±0.008 |

| EF |

72.48±6.049 |

54.82±8.803** |

67.62±4.214# |

64.46±8.395 |

76.5±7.052## |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).