Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

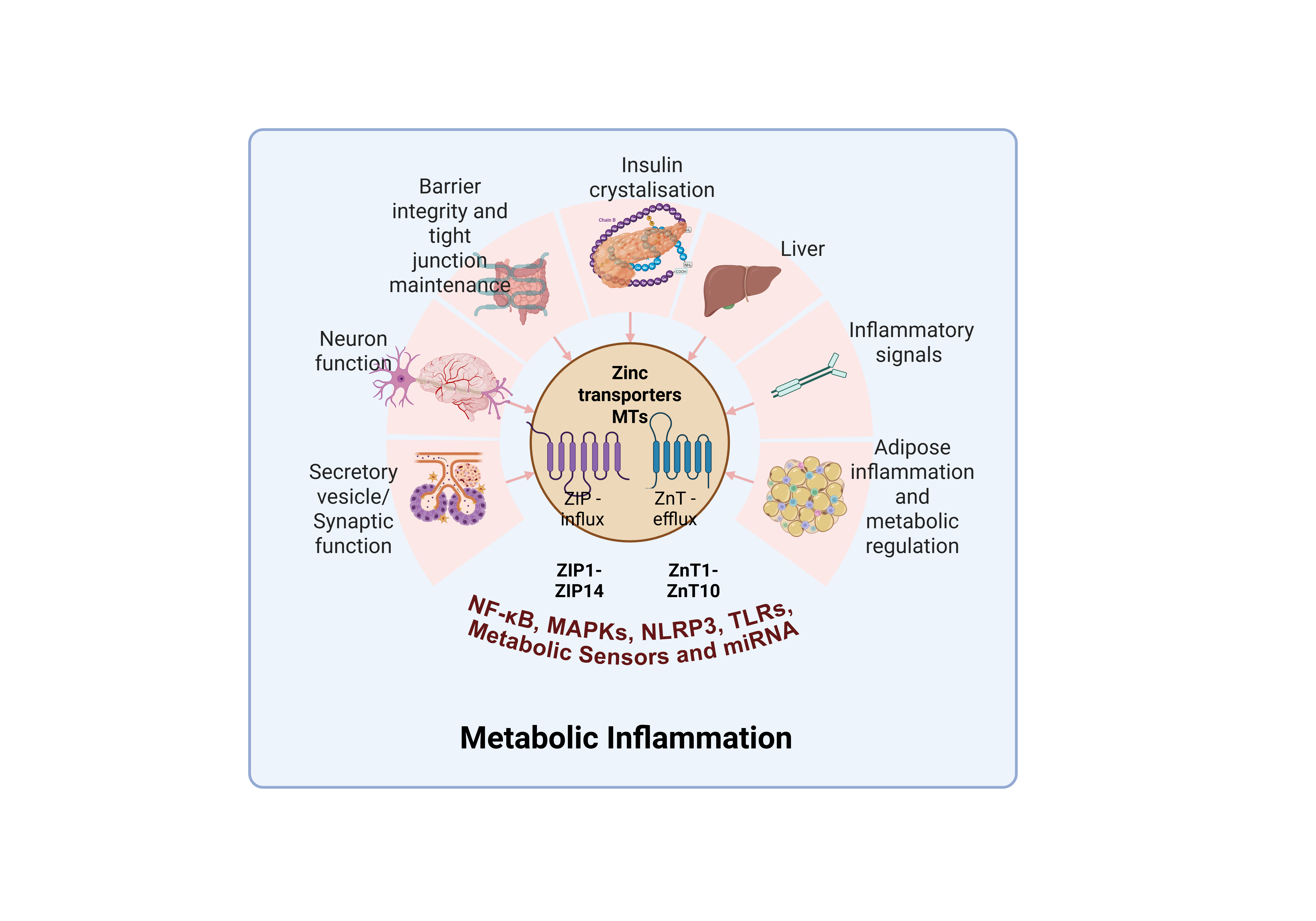

2. Key Machinery for Zinc Homeostasis

2.1. ZnT and ZIP Families: the Core Zinc Transporters

2.2. Metallothionein: A Crucial Intracellular Zinc Buffer

2.3. Key Cellular Zinc Compartments and Organelle-Specific Zinc Trafficking.

| Organelle | Transporters Involved | Function & Physiological Significance | Key Experimental Study Details & Insights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | ZIP family (influx), ZnT family (efflux into organelles/extracellular space) | Maintains low free Zn²⁺ (picomolar) to support signaling and prevent toxicity; main hub for zinc-sensitive enzymes and kinases. | ZIP1/ZIP3 found in intracellular organelles (HEK293, mouse), localize dynamically based on zinc status .Cytosolic zinc wave observed in mast cells, dependent on ZIP/ZnT activity. | [31] |

| Secretory Vesicles(e.g., synaptic, insulin granules) | ZnT3, ZnT8, ZnT2, ZnT4 | Accumulate high vesicular zinc (millimolar range); ZnT3 loads synaptic vesicles (neurons); ZnT8 loads insulin granules (pancreatic β cells); ZnT2 regulates glandular vesicles; ZnT4 traffics vesicles in secretory tissues. | ZnT8 knockout and variant studies confirm granule-specific insulin packaging/diabetes risk. ZnT3 is involved in heterogeneous synaptic vesicle assembly and neurotransmission. ZnT2 is critical for zinc vesicle formation and stress protection. | [32,33,34,35,36,37,38] |

| Golgi Apparatus & ER | ZnT5, ZnT6, ZnT7 (influx into lumen); ZIP7, ZIP13 (efflux into cytosol) | Zinc is required for folding and activation of secreted/membrane proteins, e.g., tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), ERp44; ZIP exports zinc in "zinc wave" for cytosolic signaling; ZnT5/6/7 localized to Golgi & ER, essential for ALP activation. | ZnT5 variant B localizes to ER, colocalizes with ZIP7, forming zinc efflux pathway; ZIP7 essential for cytosolic zinc signaling. ZnT7 localizes to proximal Golgi and regulates ERp44-dependent homeostasis. ZnT5/6/7 activate tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase in two-step mechanism. | [17,20,21,39,40,41] |

| Mitochondria | ZnT2 (suggested), ZnT9 (SLC30A9), ZIP family (potential roles) | Mitochondrial zinc pools regulate oxidative metabolism, apoptosis, mitophagy; zinc influx/efflux affects mitochondrial stress resilience and cytochrome c release. | SLC30A9 (ZnT9) loss causes zinc mishandling and mitochondrial overload in HeLa cells, shown by live dye tracking and ERC coevolution analysis. Zn-induced mitochondrial swelling triggers mPTP opening, mediates apoptosis. | [24,42,43,44,45] |

| Lysosome-Related Organelles (LROs) | CDF-2 (ZnT family), ZIPT-2.3 (ZIP family, C. elegans), ZnT4 | Dynamic zinc storage and release; maintain organellar zinc pools for protein degradation/homeostasis, critical in stress adaptation. | In C. elegans, CDF-2 stores zinc in LROs during excess, ZIPT-2.3 releases zinc during deficiency; co-regulation and colocalization confirmed by super-resolution microscopy and transgenics. Morphologic changes reflect zinc status, transporter levels. | [46] |

| Nucleus | Metallothioneins (MTs), potential transporters | Zinc primarily bound to transcription factors (zinc fingers), essential for gene expression/DNA replication; labile pool controls TF binding/dynamics. | Single-molecule microscopy reveals that zinc availability modulates DNA binding of zinc finger TFs (MTF-1, CTCF, GR) in live mammalian cells; zinc depletion shortens TF dwell time .MTs buffer nuclear zinc and protect against oxidative injury . | [47,48] |

3. Functional Links Between Zinc and Metaflammation

3.1. The Influence of Zinc Transporter Imbalance in Metaflammation

3.2. Zinc Transporters and microRNA-Mediated Regulation of Metaflammation

| Pathogenic Trigger | Zinc-Related Impact | Inflammatory Outcome / Mechanism | Mechanistic/Clinical Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFAs, ROS, glucose overload | Disrupt zinc transporter expression: ZIP14 ↑ (in hepatocytes, adipocytes), ZnT8 ↓ (in pancreatic β-cells) | NLRP3 inflammasome activation, increased IL-1β/IL-18 release, chronic metabolic inflammation | ZIP14 upregulation in response to TLR4 activation and IL-6 drives hepatic/adipose zinc accumulation and insulin resistance. ZnT8 downregulation impairs insulin granule formation and β-cell function. High glucose and ROS amplify IL-1β/IL-18 via NLRP3 . | [54,67,68] |

| Zinc deficiency | Reduced Treg cell numbers, increased NF-κB activation; impaired metallothionein buffering | Chronic low-grade inflammation, heightened NLRP3 activation, increased cytokine output | Zn deficiency leads to lysosomal stress, ROS generation, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation/secretion of IL-1β .Zinc supplementation inhibits NLRP3 and supports immune balance. | [59,70,74] |

| Zinc transporter dysfunction | Alters zinc distribution in pancreas (ZnT8), liver/adipose (ZIP14), gut (ZnT2/ZIP8) | Insulin resistance, gut barrier leakiness, cytokine imbalance | Genetic or acquired dysfunction in ZnT8/ZIP14 impairs insulin packaging/secretion and hepatic/adipose zinc homeostasis. ZnT2/ZIP8 regulate intestinal barrier integrity; dysfunction increases permeability and systemic inflammation. | [67,68,75,76] |

| Oxidative stress | Displaces zinc from protein binding sites, impairs antioxidant function | Amplifies ROS, triggers NLRP3 activation, further immune cell recruitment and cytokine release | Oxidative stress displaces zinc, activates stress kinases, and amplifies proinflammatory signaling. Zinc repletion reduces ROS and NLRP3 activity, supporting antioxidant defenses. | [59,77] |

4. Tissue-Specific Roles of Zinc Transporters

| Tissue | Zinc Transporters | Functions | Pathological Implications & Supporting Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | ZIP14, ZIP8, ZIP1, ZIP10, ZnT1, ZnT5, ZnT6 | ZIPs mediate hepatic zinc uptake (ZIP14, ZIP8), respond to inflammation/acute phase (ZIP14); ZIP1/ZIP10 support vesicular influx; ZnT1 exports zinc. | Dysregulated ZIP14 leads to hepatic inflammation, NAFLD, and insulin resistance; ZnT1 alterations impact systemic zinc homeostasis. ZIP1 transits between plasma membrane and intracellular vesicles based on zinc levels. | [79,81,107,108,109] |

| Pancreas | ZnT8, ZnT5, ZnT7, ZIP6, ZIP7, ZIP8, ZIP1 | ZnT8 loads zinc into insulin granules for packaging/maturation (T2D linkage); ZnT5/7 regulate zinc in ER/Golgi for hormone biosynthesis; ZIPs maintain cytosolic/organelle zinc homeostasis; ZIP1 & ZIP3 is detected in mouse/pig pancreatic tissue. | ZnT8 dysfunction causes β-cell failure, impaired insulin secretion, and diabetes risk; ZIP6/7/8 impairment affects proinsulin processing and stress responses in beta cells. ZIP1 can localize to vesicular structures in transfected cells. | [37,87,110] |

| Adipose Tissue | ZIP14, ZIP13, ZIP8, ZIP1, ZnT7, ZnT5 | ZIP14 mediates zinc influx during inflammation, impacts immune signaling; ZIP13 regulates secretory pathway and adipocyte differentiation/BMP/TGF-β signaling (knockout leads to vesicular zinc build-up in fibroblasts); ZnT7 influences fat metabolism. | ZIP13 dysfunction leads to adipose inflammation and altered fat mass. ZIP14 upregulation is linked with metabolic syndrome and obesity-associated inflammation. ZnT7 influences insulin sensitivity and adiposity. ZIP1 and ZIP8 involved in adipocyte zinc homeostasis and cytokine response. | [91,96,97,111,112] |

| Gut (Intestine) | ZIP4, ZIP8, ZIP1, ZIP10, ZnT1, ZnT2, ZnT4 | ZIP4 mediates dietary zinc absorption on apical surface (ZIP4 mutations: acrodermatitis enteropathica); ZIP8 maintains immune cell zinc levels; ZIP1/ZIP10 contribute to epithelial zinc balance; ZnT1 exports into circulation (basolateral), ZnT2 supports zinc granule secretion in Paneth/goblet cells. | ZIP4 essential for intestinal health and systemic zinc; ZnT1 expressed highly in gut, supporting serum zinc levels. ZnT4 contributes to vesicle trafficking in enterocytes. ZIP8, ZIP1, ZIP10 regulate intestinal immunity and barrier integrity. | [99,100,101,104,113,114] |

| Kidney | ZIP8, ZIP1, ZnT3, ZIP10, ZnT1, ZnT4, ZnT8 | ZIPs/ZnTs support renal zinc reabsorption, homeostasis, and excretion; ZnT1/2 mRNA unique in kidney; ZnT4 and ZnT6 traffic in vesicular compartment. | Zinc imbalance impairs kidney function, ZnT3/ZIP8/ZIP1 changes affect nephropathy risk; transporter regulation controls acute-phase systemic zinc redistribution. | [60,115,116,117,118] |

| Brain | ZIP3, ZIP8, ZIP1, ZIP6, ZIP7, ZnT1, ZnT3, ZnT4, ZnT6 | ZnT3 loads zinc into synaptic vesicles for neurotransmission; ZIP3/8/1/6 manage neuronal zinc influx and homeostasis; ZIP7 located constitutively in Golgi/ER in neurons and glia; ZnT4, ZnT6 detected in neural vesicles. | ZnT3 critical for synaptic plasticity, alteration linked to neurodegeneration; ZIP7 antibody stains Golgi/ER regions in diverse cell types, including neurons and glia. Transporter imbalance may affect cognition and neuroinflammation. | [119,120,121] |

5. Zinc-Modulated Signaling Pathways

5.1. Zinc’s Crosstalk with Canonical Pathways: NF-κB, MAPKs, NLRP3, TLRs,

| Signaling Pathway | Zinc’s Role | Physiological Impact | Study Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Waves | Acts as a second messenger; rapid release from ER/perinuclear stores after receptor stimulation (FcεRI, TLR, cAMP/PKA) | Modulates protein tyrosine phosphatase activity, prolongs MAPK activation, amplifies/controls cytokine (IL-6, TNF-α) production | Zinc waves occur within minutes after FcεRI crosslinking, dependent on Ca²⁺ and MEK signals. Inhibits phosphatases and sustains MAPKs; first described in mast cells. | [1] |

| NF-κB | Inhibits IκB kinase (IKK), stabilizes IκB, directly and indirectly restricts NF-κB nuclear translocation | Suppresses pro-inflammatory gene expression (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β); zinc deficiency or transporter dysfunction relieves this suppression | Zinc wave enhances cytokine gene induction via prolonged MAPK and potentially NF-κB activation after FcεRI stimulation .Zinc essentially gates the amplitude/duration of the NF-κB response . | [1,9,54] |

| MTF-1 | Direct zinc sensor; zinc binding activates metal response elements, upregulating metallothioneins and select ZnT genes | Promotes cellular defense against oxidative stress; increases zinc buffering capacity; adapts transporter profile to stress | Zinc exposure or cytosolic elevation leads to MTF-1 nuclear translocation and oxidative stress protection, well-documented in immune and liver cells . | [16] |

| MAPKs (ERK, JNK, p38) | Zinc waves/influx modulate phosphorylation, inhibiting protein phosphatases, sustaining MAPK signaling | Controls cell proliferation, inflammation, cytokine output, and survival/differentiation signals | Zinc ionophores mimic zinc wave by prolonging MAPK activation, increasing late-phase IL-6/TNF-α expression in mast cells . | [1] |

| NLRP3 Inflammasome | Zinc deficiency or oxidation-driven displacement of zinc from proteins activates NLRP3 inflammasome, increases IL-1β | Promotes metaflammation, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammatory disease | Zinc supplementation inhibits NLRP3 activation; deficiency/oxidative stress enhances it. Linked to response in macrophages, adipose tissue . | [54] |

| TLRs | Zinc suppresses MyD88 and canonical NF-κB pathway activation in TLR4/2 signaling, modulates inflammatory threshold | Prevents excessive cytokine release on microbial/metabolic stimulation; restricts prolonged inflammation | TLR activation results in rapid transporter regulation and a decrease in free zinc as an early signal for dendritic cell activation. ZIP14 and ZIP8 up/downregulation tightly couple TLR activity to zinc homeostasis. | [93,130] |

| Insulin Signaling | Zinc enhances Akt activation, supports phosphorylation cascade; ZnT8 ensures proper insulin packaging/release | Promotes glucose uptake, insulin secretion, and β-cell function; deficiency linked to impaired glycemic control | ZnT8 mutations disrupt insulin granule biogenesis and secretion, increasing T2D risk. Zinc signaling also influences IRS-1/PI3K/Akt sensitivity in target tissues. | [133,134] |

6. Therapeutic Implications and Translational Potential of Zinc Transporters

6.1. Pharmaceutical Development and Contemporary Case Analyses:

| Zinc Transporter / Target | Mechanism / Rationale | Disease / Condition | Drug/Intervention Type | Study Details | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnT8 | Zinc transport into insulin granules (β-cell specific); impacts insulin maturation and secretion | Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) | Targeted modulator / Precision therapy (in development) | GWAS and rare variant studies: loss-of-function alleles reduce T2D risk .Ongoing drug development focused on enhancing or mimicking protective variants. ZnT8-KO mouse studies confirm islet-specific function. | [154,155] |

| ZIP5 | Regulates glucose sensing & insulin secretion in β-cells; impacts gut/pancreas zinc handling | Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases | Small molecule/Genetic modulation (preclinical) | Mouse knockout protects against glucose dysregulation and pancreatic zinc toxicity. SLC39A5 variants studied in large cohorts; shown to modulate serum zinc and glucose homeostasis in humans and animals. | [146] |

| ZIP8 | Modulates zinc uptake in gut/liver/adipose; influences innate immunity, metabolism, Crohn's disease risk | Crohn's Disease, Gut/Liver Inflammation | Genetic and pharmacological modulation (early translational phase) | Functional variant linked with Crohn's disease and microbiome composition. Modifiers of ZIP8 studied in immune/inflammatory disease animal models. | [156,157] |

| ZIP10 | Controls B-cell receptor signaling, humoral immunity, anti-apoptotic signaling | Hematologic malignancy, Immunodeficiency | Genetic targeting / Therapeutic antibodies (preclinical) | ZIP10 critical for B cell survival; mouse genetic studies. ZIP10 inhibitors/enhancers under investigation for immune modulation; drug development in early preclinical phase. | [158] |

| ZIP13 | Regulates vascular and cardiac/skin function; upregulation linked to fibrosis and inflammation | Cardiovascular disease, Fibrosis | Small molecule inhibitor / antisense RNA (in development) | Mouse ZIP13 downregulation reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury via CaMKII regulation. Pharmacologic inhibition as a therapeutic strategy is under study. | [159] |

| ZIP4 | Dietary zinc absorption / homeostasis; overexpression in cancer | Pancreatic & GI cancers, Acrodermatitis Enteropathica | Antibody drugs / Antisense oligonucleotides | Anti-ZIP4 therapies in preclinical cancer studies. Genetic therapies for acrodermatitis enteropathica under development. | [99,160] |

| ZnT1 | Exports zinc from cells; affects systemic and tissue zinc levels | Zinc deficiency/excess, intestinal disorders | Dietary/Pharmacological / Translational biomarker | Plays a role in dietary and supplemental zinc absorption; involved in biomarker trial (NCT01062347) . | [161,162] |

| SLC transporters (class) | General therapeutic target class: several subtypes including SLC30A, SLC39A individually druggable | T2D, metabolic, cancer, inflammation | Small molecule/Monoclonal antibodies/combo therapy | SLC30A8 and related SLCs identified as most promising for metabolic indications from human genetic & animal studies; some SLCs targeted in marketed and experimental cancer/metabolic drugs. | [163,164,165] |

7. Future Perspectives and Open Questions

References

- Chen, B.; Yu, P.; Chan, W.N.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Leung, K.T.; Lo, K.W.; Yu, J.; Tse, G.M.K.; et al. Cellular Zinc Metabolism and Zinc Signaling: From Biological Functions to Diseases and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Kambe, T. The Functions of Metallothionein and ZIP and ZnT Transporters: An Overview and Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 336. [CrossRef]

- Charles-Messance, H.; Mitchelson, K.A.J.; Castro, E.D.M.; Sheedy, F.J.; Roche, H.M. Regulating Metabolic Inflammation by Nutritional Modulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 706–720. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Troche, C.; Kim, M.-H.; Cousins, R.J. Hepatic ZIP14-Mediated Zinc Transport Contributes to Endosomal Insulin Receptor Trafficking and Glucose Metabolism*. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23939–23951. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Diabetes and Zinc Dyshomeostasis: Can Zinc Supplementation Mitigate Diabetic Complications? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1046–1061. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Pradeep, S.R.; Srinivasan, K. Zinc Supplementation Mitigates Its Dyshomeostasis in Experimental Diabetic Rats by Regulating the Expression of Zinc Transporters and Metallothionein†. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1765–1777. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Ameliorative Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Compromised Small Intestinal Health in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 307, 37–50. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-G.; Wu, T.-Y.; Zhao, L.-X.; Jia, R.-J.; Ren, H.; Hou, W.-J.; Wang, Z.-Y. From Zinc Homeostasis to Disease Progression: Unveiling the Neurodegenerative Puzzle. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 199, 107039. [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Silwal, P.; Sasakawa, C.; Jo, E.-K. An Update on the Regulatory Mechanisms of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1141–1160. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Eide, D.J. The SLC39 Family of Zinc Transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 612–619. [CrossRef]

- Kambe, T.; Taylor, K.M.; Fu, D. Zinc Transporters and Their Functional Integration in Mammalian Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100320. [CrossRef]

- Roca-Umbert, A.; Garcia-Calleja, J.; Vogel-González, M.; Fierro-Villegas, A.; Ill-Raga, G.; Herrera-Fernández, V.; Bosnjak, A.; Muntané, G.; Gutiérrez, E.; Campelo, F.; et al. Human Genetic Adaptation Related to Cellular Zinc Homeostasis. PLOS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010950. [CrossRef]

- Krężel, A.; Maret, W. The Bioinorganic Chemistry of Mammalian Metallothioneins. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 14594–14648. [CrossRef]

- Bafaro, E.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dempski, R.E. The Emerging Role of Zinc Transporters in Cellular Homeostasis and Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17029. [CrossRef]

- Oteiza, P.I. Zinc and the Modulation of Redox Homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1748–1759. [CrossRef]

- Laity, J.H.; Andrews, G.K. Understanding the Mechanisms of Zinc-Sensing by Metal-Response Element Binding Transcription Factor-1 (MTF-1). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 463, 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Amagai, Y.; Sannino, S.; Tempio, T.; Anelli, T.; Harayama, M.; Masui, S.; Sorrentino, I.; Yamada, M.; Sitia, R.; et al. Zinc Regulates ERp44-Dependent Protein Quality Control in the Early Secretory Pathway. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 603. [CrossRef]

- Wagatsuma, T.; Shimotsuma, K.; Sogo, A.; Sato, R.; Kubo, N.; Ueda, S.; Uchida, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Kambe, T. Zinc Transport via ZNT5-6 and ZNT7 Is Critical for Cell Surface Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102011. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Aydemir, T.B.; Kim, J.; Cousins, R.J. Hepatic ZIP14-Mediated Zinc Transport Is Required for Adaptation to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E5805–E5814. [CrossRef]

- Amagai, Y.; Yamada, M.; Kowada, T.; Watanabe, T.; Du, Y.; Liu, R.; Naramoto, S.; Watanabe, S.; Kyozuka, J.; Anelli, T.; et al. Zinc Homeostasis Governed by Golgi-Resident ZnT Family Members Regulates ERp44-Mediated Proteostasis at the ER-Golgi Interface. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2683. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Ishihara, K.; Migaki, H.; Ishihara, K.; Nagao, M.; Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y.; Kambe, T. Two Different Zinc Transport Complexes of Cation Diffusion Facilitator Proteins Localized in the Secretory Pathway Operate to Activate Alkaline Phosphatases in Vertebrate Cells*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30956–30962. [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, H.; Morino, N.; Wagatsuma, T.; Munekane, M.; Ueda, S.; Matsunaga, M.; Uchida, Y.; Katayama, T.; Katoh, T.; Kambe, T. ZNT5-6 and ZNT7 Play an Integral Role in Protein N-Glycosylation by Supplying Zn2+ to Golgi α-Mannosidase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107378. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, N.H.; Kelleher, S.L. ZnT4 Provides Zinc to Zinc-Dependent Proteins in the Trans-Golgi Network Critical for Cell Function and Zn Export in Mammary Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2012, 303, C291–C297. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Gale, J.R.; Reynolds, I.J.; Weiss, J.H.; Aizenman, E. The Multifaceted Roles of Zinc in Neuronal Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 489. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Yo, R.; Zhang, Z.; Shimizu, T.; Ohto, U. Cryo-EM Structures of the Zinc Transporters ZnT3 and ZnT4 Provide Insights into Their Transport Mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 2025, 599, 41–52. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, O.C.; Geddes, D.T.; Barber-Zucker, S.; Zarivach, R.; Gagnon, A.; Soybel, D.I.; Kelleher, S.L. A Common Genetic Variant in Zinc Transporter ZnT2 (Thr288Ser) Is Present in Women with Low Milk Volume and Alters Lysosome Function and Cell Energetics. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C1166–C1177. [CrossRef]

- Chowanadisai, W.; Lönnerdal, B.; Kelleher, S.L. Identification of a Mutation in SLC30A2 (ZnT-2) in Women with Low Milk Zinc Concentration That Results in Transient Neonatal Zinc Deficiency*. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39699–39707. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, H.W.; Wenzlau, J.M.; O’Brien, R.M. Zinc Transporter 8 (ZnT8) and β Cell Function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 415–424. [CrossRef]

- Kukic, I.; Lee, J.K.; Coblentz, J.; Kelleher, S.L.; Kiselyov, K. Zinc-Dependent Lysosomal Enlargement in TRPML1-Deficient Cells Involves MTF-1 Transcription Factor and ZnT4 (Slc30a4) Transporter. Biochem. J. 2013, 451, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Liuzzi, J.P.; McClellan, S.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter ZIP8 (SLC39A8) and Zinc Influence IFN-γ Expression in Activated Human T Cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 86, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dufner-Beattie, J.; Kim, B.-E.; Petris, M.J.; Andrews, G.; Eide, D.J. Zinc-Stimulated Endocytosis Controls Activity of the Mouse ZIP1 and ZIP3 Zinc Uptake Transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24631–24639. [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Y. Free Zinc Determines the Formability of the Vesicular Dense Core in Diabetic Beta Cells. Cell Insight 2022, 1, 100020. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, B.B.; Dyck, R.H. Zinc Transporter 3 (ZnT3) and Vesicular Zinc in Central Nervous System Function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 329–350. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, H.W.; Wenzlau, J.M.; O’Brien, R.M. ZINC TRANSPORTER 8 (ZNT8) AND BETA CELL FUNCTION. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2014, 25, 415–424. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rivera, O.C.; Kelleher, S.L. Zinc Transporter 2 Interacts with Vacuolar ATPase and Is Required for Polarization, Vesicle Acidification, and Secretion in Mammary Epithelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 21598–21613. [CrossRef]

- Kambe, T.; Matsunaga, M.; Takeda, T. Understanding the Contribution of Zinc Transporters in the Function of the Early Secretory Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2179. [CrossRef]

- Wijesekara, N.; Dai, F.F.; Hardy, A.B.; Giglou, P.R.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Koshkin, V.; Chimienti, F.; Gaisano, H.Y.; Rutter, G.A.; Wheeler, M.B. Beta Cell Specific ZnT8 Deletion in Mice Causes Marked Defects in Insulin Processing, Crystallization and Secretion. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1656–1668. [CrossRef]

- Palmiter, R.D.; Cole, T.B.; Quaife, C.J.; Findley, S.D. ZnT-3, a Putative Transporter of Zinc into Synaptic Vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 14934–14939. [CrossRef]

- Fukunaka, A.; Kurokawa, Y.; Teranishi, F.; Sekler, I.; Oda, K.; Ackland, M.L.; Faundez, V.; Hiromura, M.; Masuda, S.; Nagao, M.; et al. Tissue Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase Is Activated via a Two-Step Mechanism by Zinc Transport Complexes in the Early Secretory Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16363–16373. [CrossRef]

- Bafaro, E.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dempski, R.E. The Emerging Role of Zinc Transporters in Cellular Homeostasis and Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17029. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.K.; Taylor, K.M.; Ford, D.; Valentine, R.A. Differential Subcellular Localization of the Splice Variants of the Zinc Transporter ZnT5 Is Dictated by the Different C-Terminal Regions. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e23878. [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Cui, Y.; Sang, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhao, H.; Mei, X. Zinc Ions Regulate Mitochondrial Quality Control in Neurons under Oxidative Stress and Reduce PANoptosis in Spinal Cord Injury Models via the Lgals3-Bax Pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 221, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Sadykhov, N.K.; Kartuesov, A.G.; Borisov, E.E.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. Interplay between Zn2+ Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Functions in Cardiovascular Diseases and Heart Ageing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6890. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Qiao, X.; Xie, T.; Fu, W.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, M.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. SLC-30A9 Is Required for Zn2+ Homeostasis, Zn2+ Mobilization, and Mitochondrial Health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, e2023909118. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Sullivan, P.G.; Sensi, S.L.; Steward, O.; Weiss, J.H. Zn2+ Induces Permeability Transition Pore Opening and Release of Pro-Apoptotic Peptides from Neuronal Mitochondria *. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 47524–47529. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, A.D.; Dietrich, N.; Tan, C.-H.; Herrera, D.; Kasiah, J.; Payne, Z.; Cubillas, C.; Schneider, D.L.; Kornfeld, K. Lysosome-Related Organelles Contain an Expansion Compartment That Mediates Delivery of Zinc Transporters to Promote Homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121, e2307143121. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Kambe, T. The Functions of Metallothionein and ZIP and ZnT Transporters: An Overview and Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 336. [CrossRef]

- Lichtlen, P.; Schaffner, W. Putting Its Fingers on Stressful Situations: The Heavy Metal-regulatory Transcription Factor MTF-1. BioEssays 2001, 23, 1010–1017. [CrossRef]

- Charles-Messance, H.; Mitchelson, K.A.J.; De Marco Castro, E.; Sheedy, F.J.; Roche, H.M. Regulating Metabolic Inflammation by Nutritional Modulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 706–720. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Foundations of Immunometabolism and Implications for Metabolic Health and Disease. Immunity 2017, 47, 406–420. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [CrossRef]

- Diet Review: Anti-Inflammatory Diet • The Nutrition Source 2021.

- Milanski, M.; Degasperi, G.; Coope, A.; Morari, J.; Denis, R.; Cintra, D.E.; Tsukumo, D.M.L.; Anhe, G.; Amaral, M.E.; Takahashi, H.K.; et al. Saturated Fatty Acids Produce an Inflammatory Response Predominantly through the Activation of TLR4 Signaling in Hypothalamus: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Obesity. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 359–370. [CrossRef]

- Finucane, O.M.; Lyons, C.L.; Murphy, A.M.; Reynolds, C.M.; Klinger, R.; Healy, N.P.; Cooke, A.A.; Coll, R.C.; McAllan, L.; Nilaweera, K.N.; et al. Monounsaturated Fatty Acid–Enriched High-Fat Diets Impede Adipose NLRP3 Inflammasome–Mediated IL-1β Secretion and Insulin Resistance Despite Obesity. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2116–2128. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Chang, K.; Wu, W.; Griffiths, H.R.; Lu, S.; Gao, D. Adipose Tissue Macrophages as Potential Targets for Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1153915. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Zinc Supplementation Ameliorates Diabetic Cataract Through Modulation of Crystallin Proteins and Polyol Pathway in Experimental Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 187, 212–223. [CrossRef]

- Izgilov, R.; Kislev, N.; Omari, E.; Benayahu, D. Advanced Glycation End-Products Accelerate Amyloid Deposits in Adipocyte’s Lipid Droplets. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 846. [CrossRef]

- Asadipooya, K.; Lankarani, K.B.; Raj, R.; Kalantarhormozi, M. RAGE Is a Potential Cause of Onset and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 2151302. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Attenuation of Oxidative Stress and Cardioprotective Effects of Zinc Supplementation in Experimental Diabetic Rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 335–350. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Pradeep, S.R.; Srinivasan, K. Zinc Supplementation Alleviates the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting the Overexpression of Oxidative-Stress-Mediated Molecular Markers in Streptozotocin-Induced Experimental Rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 54, 113–129. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation, Metaflammation and Immunometabolic Disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Marreiro, D. do N.; Cruz, K.J.C.; Morais, J.B.S.; Beserra, J.B.; Severo, J.S.; de Oliveira, A.R.S. Zinc and Oxidative Stress: Current Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wessels, I.; Maywald, M.; Rink, L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1286. [CrossRef]

- Wessels, I.; Haase, H.; Engelhardt, G.; Rink, L.; Uciechowski, P. Zinc Deficiency Induces Production of the Proinflammatory Cytokines IL-1β and TNFα in Promyeloid Cells via Epigenetic and Redox-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Dierichs, L.; Kloubert, V.; Rink, L. Cellular Zinc Homeostasis Modulates Polarization of THP-1-Derived Macrophages. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2161–2169. [CrossRef]

- Kulik, L.; Maywald, M.; Kloubert, V.; Wessels, I.; Rink, L. Zinc Deficiency Drives Th17 Polarization and Promotes Loss of Treg Cell Function. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 63, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, J.P.; Lichten, L.A.; Rivera, S.; Blanchard, R.K.; Aydemir, T.B.; Knutson, M.D.; Ganz, T.; Cousins, R.J. Interleukin-6 Regulates the Zinc Transporter Zip14 in Liver and Contributes to the Hypozincemia of the Acute-Phase Response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 6843–6848. [CrossRef]

- Merriman, C.; Fu, D. Down-Regulation of the Islet-Specific Zinc Transporter-8 (ZnT8) Protects Human Insulinoma Cells against Inflammatory Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 16992–17006. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-J.; Bao, S.; Gálvez-Peralta, M.; Pyle, C.J.; Rudawsky, A.C.; Pavlovicz, R.E.; Killilea, D.W.; Li, C.; Nebert, D.W.; Wewers, M.D.; et al. ZIP8 Regulates Host Defense through Zinc-Mediated Inhibition of NF-κB. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 386–400. [CrossRef]

- Summersgill, H.; England, H.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Lawrence, C.B.; Luheshi, N.M.; Pahle, J.; Mendes, P.; Brough, D. Zinc Depletion Regulates the Processing and Secretion of IL-1β. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1040. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Rondan, F.R.; Ruggiero, C.H.; Cousins, R.J. Long Noncoding RNA, MicroRNA, Zn Transporter Zip14 (Slc39a14) and Inflammation in Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5114. [CrossRef]

- Taslim, N.A.; Graciela, A.M.; Harbuwono, D.S.; Syauki, A.Y.; Anthony, A.N.; Ashari, N.; Aman, A.M.; Tjandrawinata, R.R.; Hardinsyah, H.; Bukhari, A.; et al. Zinc as a Modulator of miRNA Signaling in Obesity. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3375. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cheng, M.; Fan, L.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, P.; Xie, Y.; You, X.; Zhou, M.; Wang, B.; et al. Plasma microRNA Expression Profiles Associated with Zinc Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Exploring Potential Role of miR-144-3p in Zinc-Induced Insulin Resistance. Environ. Int. 2023, 172, 107807. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Zinc Supplementation Alleviates Hyperglycemia and Associated Metabolic Abnormalities in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 94, 1356–1365. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.B.; Aydemir, T.B. Roles of Zinc and Zinc Transporters in Development, Progression, and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1649658. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, B. The Impact of Zinc and Zinc Homeostasis on the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier and Intestinal Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 900. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Bian, A.; Liu, J.; Ma, J. Zinc Inhibits High Glucose-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Human Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 5195–5202. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Cousins, R.J. The Multiple Faces of the Metal Transporter ZIP14 (SLC39A14). J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 174–184. [CrossRef]

- Winslow, J.W.W.; Limesand, K.H.; Zhao, N. The Functions of ZIP8, ZIP14, and ZnT10 in the Regulation of Systemic Manganese Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3304. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Chang, S.-M.; Guthrie, G.J.; Maki, A.B.; Ryu, M.-S.; Karabiyik, A.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter ZIP14 Functions in Hepatic Zinc, Iron and Glucose Homeostasis during the Innate Immune Response (Endotoxemia). PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48679. [CrossRef]

- Gartmann, L.; Wex, T.; Grüngreiff, K.; Reinhold, D.; Kalinski, T.; Malfertheiner, P.; Schütte, K. Expression of Zinc Transporters ZIP4, ZIP14 and ZnT9 in Hepatic Carcinogenesis—An Immunohistochemical Study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 49, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Feng, M.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R.; Liu, Y.; Tang, J.; Pan, K.; Lan, R.; Mao, Z. ZnT8 Deficiency Protects From APAP-Induced Acute Liver Injury by Reducing Oxidative Stress Through Upregulating Hepatic Zinc and Metallothioneins. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Germanos, M.; Gao, A.; Taper, M.; Yau, B.; Kebede, M.A. Inside the Insulin Secretory Granule. Metabolites 2021, 11, 515. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, K.; Ravier, M.A.; Schraenen, A.; Creemers, J.W.M.; Van de Plas, R.; Granvik, M.; Van Lommel, L.; Waelkens, E.; Chimienti, F.; Rutter, G.A.; et al. Insulin Crystallization Depends on Zinc Transporter ZnT8 Expression, but Is Not Required for Normal Glucose Homeostasis in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 14872–14877. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Xavier, G.; Bellomo, E.A.; McGinty, J.A.; French, P.M.; Rutter, G.A. Animal Models of GWAS-Identified Type 2 Diabetes Genes. J. Diabetes Res. 2013, 2013, 906590. [CrossRef]

- Sladek, R.; Rocheleau, G.; Rung, J.; Dina, C.; Shen, L.; Serre, D.; Boutin, P.; Vincent, D.; Belisle, A.; Hadjadj, S.; et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Risk Loci for Type 2 Diabetes. Nature 2007, 445, 881–885. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Kirschke, C.P.; Huang, L. SLC30A Family Expression in the Pancreatic Islets of Humans and Mice: Cellular Localization in the β-Cells. J. Mol. Histol. 2018, 49, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Batchuluun, B.; Ho, L.; Zhu, D.; Prentice, K.J.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Zhang, M.; Pourasgari, F.; Hardy, A.B.; Taylor, K.M.; et al. Characterization of Zinc Influx Transporters (ZIPs) in Pancreatic β Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18757–18769. [CrossRef]

- Egefjord, L.; Jensen, J.L.; Bang-Berthelsen, C.H.; Petersen, A.B.; Smidt, K.; Schmitz, O.; Karlsen, A.E.; Pociot, F.; Chimienti, F.; Rungby, J.; et al. Zinc Transporter Gene Expression Is Regulated by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines: A Potential Role for Zinc Transporters in Beta-Cell Apoptosis? BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009, 9, 7. [CrossRef]

- Troche, C.; Beker Aydemir, T.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter Slc39a14 Regulates Inflammatory Signaling Associated with Hypertrophic Adiposity. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E258–E268. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Kim, M.-H.; Kim, J.; Colon-Perez, L.M.; Banan, G.; Mareci, T.H.; Febo, M.; Cousins, R.J. Metal Transporter Zip14 (Slc39a14) Deletion in Mice Increases Manganese Deposition and Produces Neurotoxic Signatures and Diminished Motor Activity. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 5996–6006. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.B.; Thorn, T.L.; Lee, M.-T.; Kim, Y.; Comrie, J.M.C.; Bai, Z.S.; Johnson, E.L.; Aydemir, T.B. Metal Transporter SLC39A14/ZIP14 Modulates Regulation between the Gut Microbiome and Host Metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2023, 325, G593–G607. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Chang, S.-M.; Guthrie, G.J.; Maki, A.B.; Ryu, M.-S.; Karabiyik, A.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter ZIP14 Functions in Hepatic Zinc, Iron and Glucose Homeostasis during the Innate Immune Response (Endotoxemia). PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48679. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Limesand, K.; Zhao, N. Recent Progress toward Understanding the Role of ZIP14 in Regulating Systemic Manganese Homeostasis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2332–2338. [CrossRef]

- Troche, C.; Beker Aydemir, T.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter Slc39a14 Regulates Inflammatory Signaling Associated with Hypertrophic Adiposity. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E258–E268. [CrossRef]

- Tepaamorndech, S.; Kirschke, C.P.; Pedersen, T.L.; Keyes, W.R.; Newman, J.W.; Huang, L. Zinc Transporter 7 Deficiency Affects Lipid Synthesis in Adipocytes by Inhibiting Insulin-Dependent Akt Activation and Glucose Uptake. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 378–394. [CrossRef]

- Fukunaka, A.; Fukada, T.; Bhin, J.; Suzuki, L.; Tsuzuki, T.; Takamine, Y.; Bin, B.-H.; Yoshihara, T.; Ichinoseki-Sekine, N.; Naito, H.; et al. Zinc Transporter ZIP13 Suppresses Beige Adipocyte Biogenesis and Energy Expenditure by Regulating C/EBP-β Expression. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006950. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Srinivasan, K. Enhanced Intestinal Absorption of Micronutrients in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats Maintained on Zinc Supplementation. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 50, 182–187. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.K. Regulation and Function of Zip4, the Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Gene. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36, 1242–1246. [CrossRef]

- Kuliyev, E.; Zhang, C.; Sui, D.; Hu, J. Zinc Transporter Mutations Linked to Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Disrupt Function and Cause Mistrafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100269. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xiao, W.; Lei, Y.; Green, A.; Lee, X.; Maradana, M.R.; Gao, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, R.; Chennell, G.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Utilises Cellular Zinc Signals to Maintain the Gut Epithelial Barrier 2022, 2022.11.03.515052.

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, B. The Impact of Zinc and Zinc Homeostasis on the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier and Intestinal Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 900. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Rondan, F.R.; Ruggiero, C.H.; Riva, A.; Yu, F.; Stafford, L.S.; Cross, T.R.; Larkin, J.; Cousins, R.J. Deletion of Metal Transporter Zip14 Reduces Major Histocompatibility Complex II Expression in Murine Small Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2025, 122, e2422321121. [CrossRef]

- Podany, A.B.; Wright, J.; Lamendella, R.; Soybel, D.I.; Kelleher, S.L. ZnT2-Mediated Zinc Import Into Paneth Cell Granules Is Necessary for Coordinated Secretion and Paneth Cell Function in Mice. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2, 369–383. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.-X.; Lei, Z.; Wolf, P.G.; Gao, Y.; Guo, Y.-M.; Zhang, B.-K. Zinc Supplementation, via GPR39, Upregulates PKCζ to Protect Intestinal Barrier Integrity in Caco-2 Cells Challenged by Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1282–1289. [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.; Canzoniero, L.M.T. Zinc Homeostasis and Redox Alterations in Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lichten, L.A.; Ryu, M.-S.; Guo, L.; Embury, J.; Cousins, R.J. MTF-1-Mediated Repression of the Zinc Transporter Zip10 Is Alleviated by Zinc Restriction. PloS One 2011, 6, e21526. [CrossRef]

- Jou, M.-Y.; Hall, A.G.; Philipps, A.F.; Kelleher, S.L.; Lönnerdal, B. Tissue-Specific Alterations in Zinc Transporter Expression in Intestine and Liver Reflect a Threshold for Homeostatic Compensation during Dietary Zinc Deficiency in Weanling Rats. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 835–841. [CrossRef]

- Ziatdinova, M.M.; Мунирoвна, З.М.; Valova, Y.V.; В, В.Я.; Mukhammadiyeva, G.F.; Ф, М.Г.; Fazlieva, A.S.; С, Ф.А.; Karimov, D.D.; Д, К.Д.; et al. Analysis of MT1 and ZIP1 Gene Expression in the Liver of Rats with Chronic Poisoning with Cadmium Chloride. Hyg. Sanit. 2021, 100, 1298–1302. [CrossRef]

- Dufner-Beattie, J.; Huang, Z.L.; Geiser, J.; Xu, W.; Andrews, G.K. Mouse ZIP1 and ZIP3 Genes Together Are Essential for Adaptation to Dietary Zinc Deficiency during Pregnancy. Genes. N. Y. N 2000 2006, 44, 239–251. [CrossRef]

- Fukada, T.; Civic, N.; Furuichi, T.; Shimoda, S.; Mishima, K.; Higashiyama, H.; Idaira, Y.; Asada, Y.; Kitamura, H.; Yamasaki, S.; et al. The Zinc Transporter SLC39A13/ZIP13 Is Required for Connective Tissue Development; Its Involvement in BMP/TGF-β Signaling Pathways. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3642. [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Ghafouri-Taleghani, F.; Todorčević, M. Zinc and Adipose Organ Dysfunction: Molecular Insights into Obesity and Metabolic Disorders. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 117. [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, D.R.; Haq, S.; Knoell, D.L. Divalent Metal Uptake and the Role of ZIP8 in Host Defense Against Pathogens. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, R.J.; Cousins, R.J. Regulation of the Zinc Transporter ZnT-1 by Dietary Zinc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 4841–4846. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, T.; Song, Z.; Ni, P.; Zhong, M.; Su, Y.; Xie, E.; Sun, S.; Lin, Y.; et al. SLC39A8-Mediated Zinc Dyshomeostasis Potentiates Kidney Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2025, 122, e2426352122. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lu, H.; Ying, Y.; Li, H.; Shen, H.; Cai, J. Zinc and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2024, 70, 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, D.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Dong, J.; Li, L.; Chi, Z. ZnT8 Exerts Anti-Apoptosis of Kidney Tubular Epithelial Cell in Diabetic Kidney Disease Through TNFAIP3-NF-κB Signal Pathways. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 2442–2457. [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, J.P.; Blanchard, R.K.; Cousins, R.J. Differential Regulation of Zinc Transporter 1, 2, and 4 mRNA Expression by Dietary Zinc in Rats. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 46–52. [CrossRef]

- McAllister, B.B.; Dyck, R.H. Zinc Transporter 3 (ZnT3) and Vesicular Zinc in Central Nervous System Function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 329–350. [CrossRef]

- Grubman, A.; Lidgerwood, G.E.; Duncan, C.; Bica, L.; Tan, J.-L.; Parker, S.J.; Caragounis, A.; Meyerowitz, J.; Volitakis, I.; Moujalled, D.; et al. Deregulation of Subcellular Biometal Homeostasis through Loss of the Metal Transporter, Zip7, in a Childhood Neurodegenerative Disorder. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 25. [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, S.; Rostamirad, M.; Dempski, R.E. Unlocking the Brain’s Zinc Code: Implications for Cognitive Function and Disease. Front. Biophys. 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Alshawaf, A.J.; Alnassar, S.A.; Al-Mohanna, F.A. The Interplay of Intracellular Calcium and Zinc Ions in Response to Electric Field Stimulation in Primary Rat Cortical Neurons in Vitro. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, M.; Olbert, M.; Wyszogrodzka, G.; Młyniec, K.; Librowski, T. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Zinc. Zinc-Dependent NF-κB Signaling. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yu, P.; Chan, W.N.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Leung, K.T.; Lo, K.W.; Yu, J.; Tse, G.M.K.; et al. Cellular Zinc Metabolism and Zinc Signaling: From Biological Functions to Diseases and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Anson, K.J.; Corbet, G.A.; Palmer, A.E. Zn2+ Influx Activates ERK and Akt Signaling Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118, e2015786118. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yang, C.; Liu, D.; Zhi, Q.; Hua, Z.-C. Zinc Depletion Induces JNK/P38 Phosphorylation and Suppresses Akt/mTOR Expression in Acute Promyelocytic NB4 Cells. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127264. [CrossRef]

- Summersgill, H.; England, H.; Lopez-Castejon, G.; Lawrence, C.B.; Luheshi, N.M.; Pahle, J.; Mendes, P.; Brough, D. Zinc Depletion Regulates the Processing and Secretion of IL-1β. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1040–e1040. [CrossRef]

- Maywald, M.; Wessels, I.; Rink, L. Zinc Signals and Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2222. [CrossRef]

- Fessler, M.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Brown, M. Toll-like Receptor Signaling Links Dietary Fatty Acids to the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2009, 20, 379–385. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, W.-W. Regulatory Role of Zinc in Immune Cell Signaling. Mol. Cells 2021, 44, 335–341. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Bao, B. Molecular Mechanisms of Zinc as a Pro-Antioxidant Mediator: Clinical Therapeutic Implications. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 164. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Eom, J.-W.; Koh, J.-Y. Mechanism of Zinc Excitotoxicity: A Focus on AMPK. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.V.T.; Nissom, P.M.; Sim, S.-L.; Yeo, J.H.M.; Chuah, S.-H.; Yap, M.G.S. Zinc as an Insulin Replacement in Hybridoma Cultures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 93, 553–563. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Du, J.; Merriman, C.; Gong, Z. Genetic, Functional, and Immunological Study of ZnT8 in Diabetes. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 1524905. [CrossRef]

- Chim, S.M.; Howell, K.; Dronzek, J.; Wu, W.; Hout, C.V.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Ye, B.; Li, A.; Brydges, S.; Arunachalam, V.; et al. Genetic Inactivation of Zinc Transporter SLC39A5 Improves Liver Function and Hyperglycemia in Obesogenic Settings. eLife 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fukunaka, A.; Fujitani, Y. Role of Zinc Homeostasis in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes and Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Horton, T.M.; Allegretti, P.A.; Lee, S.; Moeller, H.P.; Smith, M.; Annes, J.P. Zinc-Chelating Small Molecules Preferentially Accumulate and Function within Pancreatic β Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 213-222.e6. [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Wathurapatha, W.S.; Galappatthy, P.; Katulanda, P.; Jayawardena, R.; Constantine, G.R. Zinc Supplementation in Prediabetes: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Diabetes 2018, 10, 386–397. [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Jayawardena, R.; Pigera, A.; Katulanda, P.; Constantine, G.R.; Galappaththy, P. Zinc Supplementation in Pre-Diabetes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2013, 14, 52. [CrossRef]

- Chim, S.M.; Howell, K.; Dronzek, J.; Wu, W.; Hout, C.V.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Ye, B.; Li, A.; Brydges, S.; Arunachalam, V.; et al. Genetic Inactivation of Zinc Transporter SLC39A5 Improves Liver Function and Hyperglycemia in Obesogenic Settings 2021, 2021.12.08.21267440.

- Davidson, H.W.; Wenzlau, J.M.; O’Brien, R.M. ZINC TRANSPORTER 8 (ZNT8) AND BETA CELL FUNCTION. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 2014, 25, 415–424. [CrossRef]

- Bin, B.-H.; Hojyo, S.; Ryong Lee, T.; Fukada, T. Spondylocheirodysplastic Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (SCD-EDS) and the Mutant Zinc Transporter ZIP13. Rare Dis. 2014, 2, e974982. [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Ma, Q.; Kong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Chen, X.; Su, Y.; Xiao, T.; He, Q.; Wang, X.; et al. A Compound Screen Based on Isogenic hESC-Derived β Cell Reveals an Inhibitor Targeting ZnT8-Mediated Zinc Transportation to Protect Pancreatic β Cell from Stress-Induced Cell Death. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2413161. [CrossRef]

- Batta, I.; Sharma, G. Molecular Docking Simulation to Predict Inhibitors Against Zinc Transporters 2024.

- Jangid, H.; Shah, N.H.; Dar, M.A.; Wani, A.K. Identification of Potent Phytochemical Inhibitors against Mobilized Colistin Resistance: Molecular Docking, MD Simulations, ADMET, and Toxicity Predictions. Silico Res. Biomed. 2025, 1, 100013. [CrossRef]

- Chim, S.M.; Howell, K.; Dronzek, J.; Wu, W.; Hout, C.V.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Ye, B.; Li, A.; Brydges, S.; Arunachalam, V.; et al. Genetic Inactivation of Zinc Transporter SLC39A5 Improves Liver Function and Hyperglycemia in Obesogenic Settings. eLife 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoon, B.R.; Yeo, J.; In Jung, J.; Yu, K.-S.; Kim, H.C.; Yoo, S.-J.; Park, J.K.; Kang, S.W.; et al. Cytoplasmic Zinc Promotes IL-1β Production by Monocytes and Macrophages through mTORC1-Induced Glycolysis in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabi7400. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-A.; Kwak, J.-S.; Park, S.-H.; Sim, K.-Y.; Kim, S.K.; Shin, Y.; Jung, I.J.; Yang, J.-I.; Chun, J.-S.; Park, S.-G. ZIP8 Exacerbates Collagen-Induced Arthritis by Increasing Pathogenic T Cell Responses. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 560–571. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jeon, J.; Shin, M.; Won, Y.; Lee, M.; Kwak, J.-S.; Lee, G.; Rhee, J.; Ryu, J.-H.; Chun, C.-H.; et al. Regulation of the Catabolic Cascade in Osteoarthritis by the Zinc-ZIP8-MTF1 Axis. Cell 2014, 156, 730–743. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-A.; Kwak, J.-S.; Park, S.-H.; Sim, K.-Y.; Kim, S.K.; Shin, Y.; Jung, I.J.; Yang, J.-I.; Chun, J.-S.; Park, S.-G. ZIP8 Exacerbates Collagen-Induced Arthritis by Increasing Pathogenic T Cell Responses. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 560–571. [CrossRef]

- Troche, C.; Beker Aydemir, T.; Cousins, R.J. Zinc Transporter Slc39a14 Regulates Inflammatory Signaling Associated with Hypertrophic Adiposity. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E258–E268. [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Peralta, M.; Wang, Z.; Bao, S.; Knoell, D.L.; Nebert, D.W. Tissue-Specific Induction of Mouse ZIP8 and ZIP14 Divalent Cation/Bicarbonate Symporters by, and Cytokine Response to, Inflammatory Signals. Int. J. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 246–258. [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, G.; Briassoulis, P.; Ilia, S.; Miliaraki, M.; Briassouli, E. The Anti-Oxidative, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Apoptotic, and Anti-Necroptotic Role of Zinc in COVID-19 and Sepsis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1942. [CrossRef]

- Barman, N.; Haque, M.A.; Ridwan, M.; Ghosh, D.; Islam, A.B.M.M.K. Loss-of-Function Variant of SLC30A8 Rs13266634 (C > T) Protects against Type 2 Diabetes by Stabilizing ZnT8: Insights from Epidemiological and Computational Analyses. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100565. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, S.K.; Gloyn, A.L. Human Genetics as a Model for Target Validation: Finding New Therapies for Diabetes. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 960–970. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Zhao, M.; Chernikova, D.; Arias-Jayo, N.; Zhou, Y.; Situ, J.; Gutta, A.; Chang, C.; Liang, F.; Lagishetty, V.; et al. ZIP8 A391T Crohn’s Disease-Linked Risk Variant Induces Colonic Metal Ion Dyshomeostasis, Microbiome Compositional Shifts, and Inflammation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 3760–3772. [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.C.; Smith, D.R.; Dyavar, S.R.; Wyatt, T.A.; Samuelson, D.R.; Bailey, K.L.; Knoell, D.L. Critical Role of Zinc Transporter (Zip8) in Myeloid Innate Immune Cell Function and the Host Response against Bacterial Pneumonia. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 2021, 207, 1357–1370. [CrossRef]

- Miyai, T.; Hojyo, S.; Ikawa, T.; Kawamura, M.; Irié, T.; Ogura, H.; Hijikata, A.; Bin, B.-H.; Yasuda, T.; Kitamura, H.; et al. Zinc Transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 Facilitates Antiapoptotic Signaling during Early B-Cell Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 11780–11785. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Z. Downregulation of the Zinc Transporter SLC39A13 (ZIP13) Is Responsible for the Activation of CaMKII at Reperfusion and Leads to Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mouse Hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 152, 69–79. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hiscox, S.; Guo, G.; Apte, U.; Taylor, K.; Sheline, C.; Wang, L.; Andrews, G. Zip4 (Slc39a4) Expression Is Activated in Hepatocellular Carcinomas and Functions to Repress Apoptosis, Enhance Cell Cycle and Increase Migration. PloS One 2010, 5. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xie, E.; Xu, S.; Ji, S.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, R.; Shen, X.; Su, Y.; Song, Z.; et al. The Intestinal Transporter SLC30A1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Systemic Zinc Homeostasis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2406421. [CrossRef]

- Trial | NCT01062347 Available online: https://cdek.pharmacy.purdue.edu/trial/NCT01062347/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Hara, T.; Yoshigai, E.; Ohashi, T.; Fukada, T. Zinc Transporters as Potential Therapeutic Targets: An Updated Review. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 148, 221–228. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, C. Analysis of the Prognostic Significance of Solute Carrier (SLC) Family 39 Genes in Breast Cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20200764. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhu, Z.; Ren, S.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Sui, X.; Jin, L.; Sun, X. Zinc Transporters Serve as Prognostic Predictors and Their Expression Correlates with Immune Cell Infiltration in Specific Cancer: A Pan-Cancer Analysis. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 939–954. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).