Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

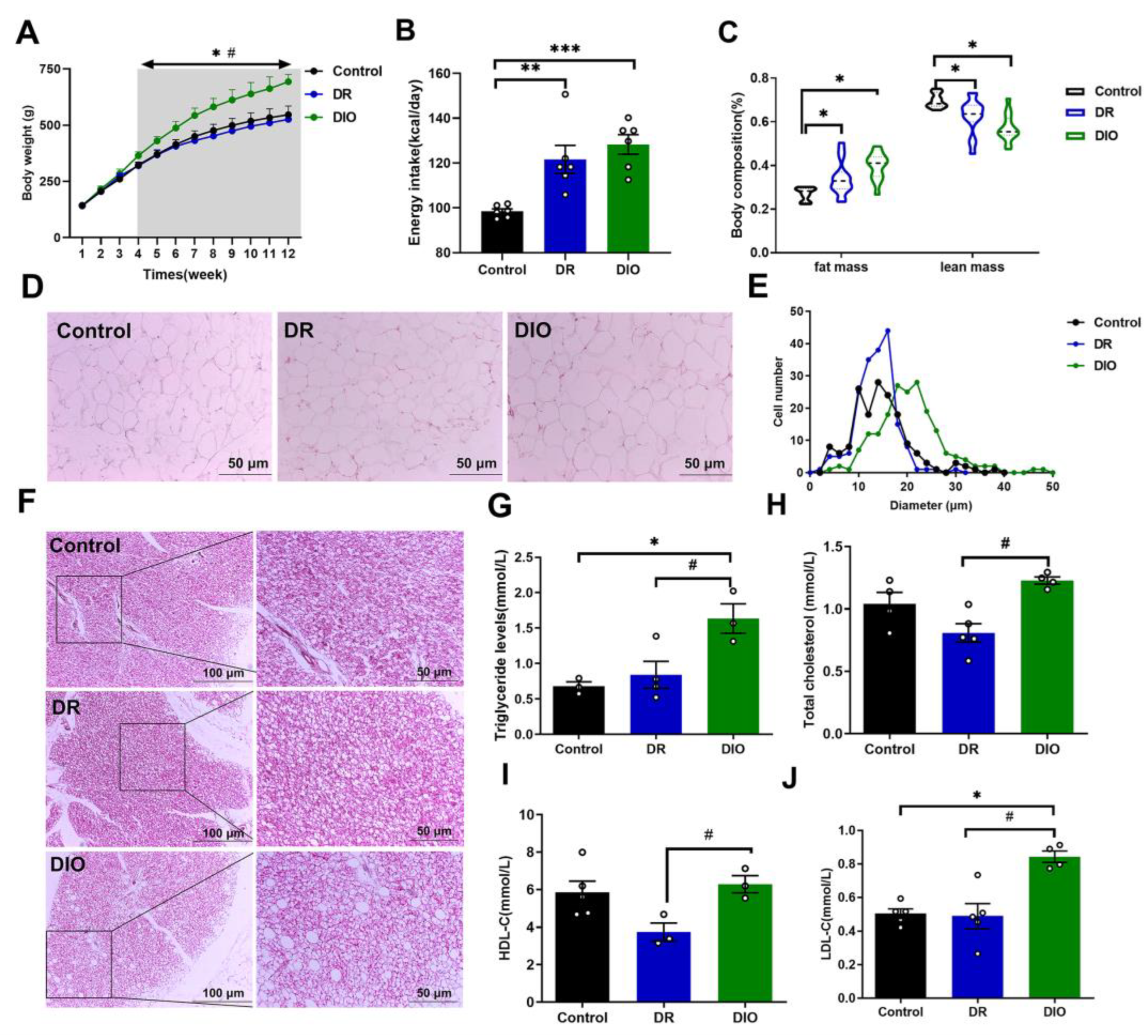

2.1. The Differences in Metabolic Characteristics between DIO and DR Rats

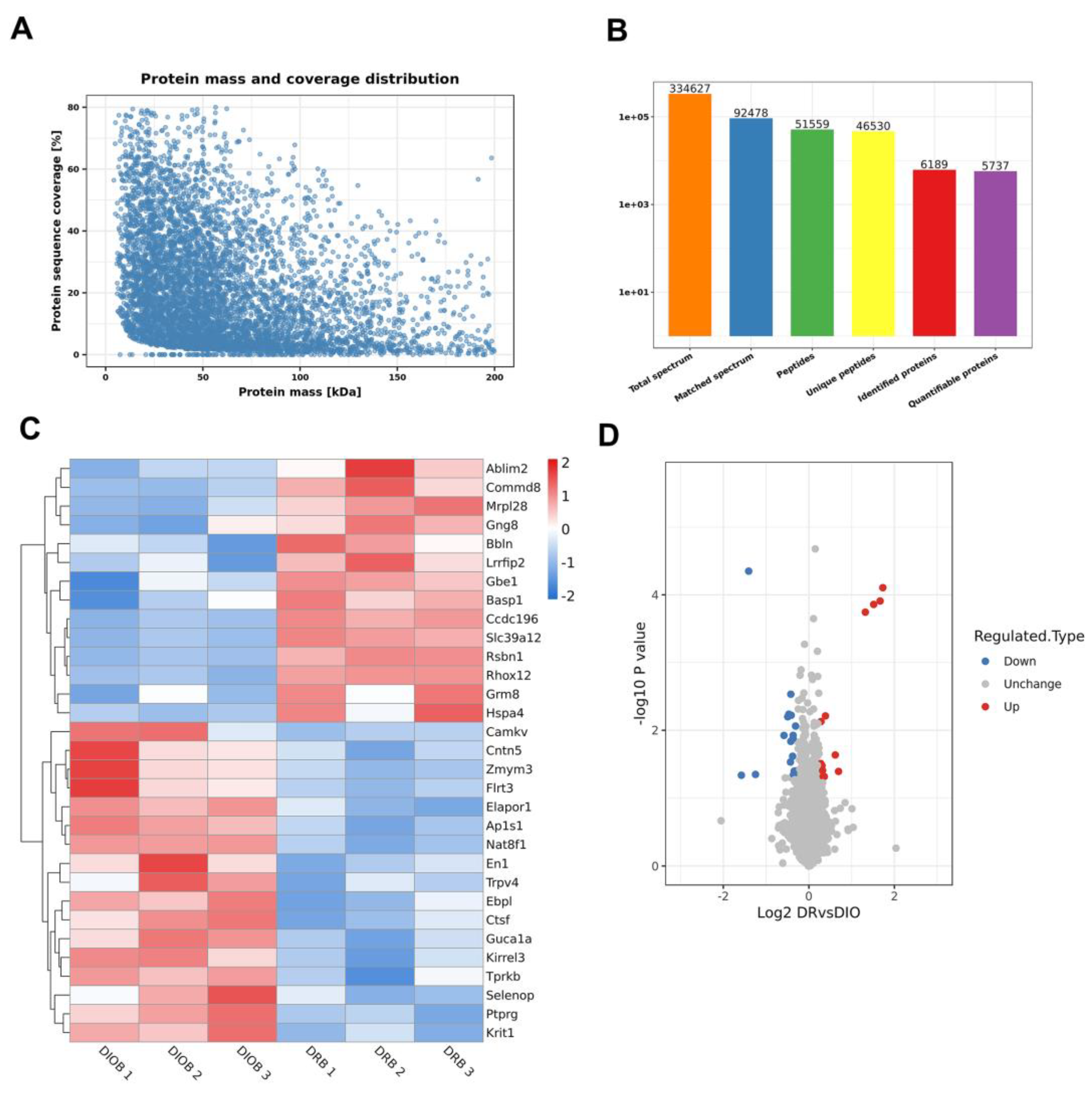

2.2. Proteomics Analysis of Hypothalamus in DIO and DR Rats

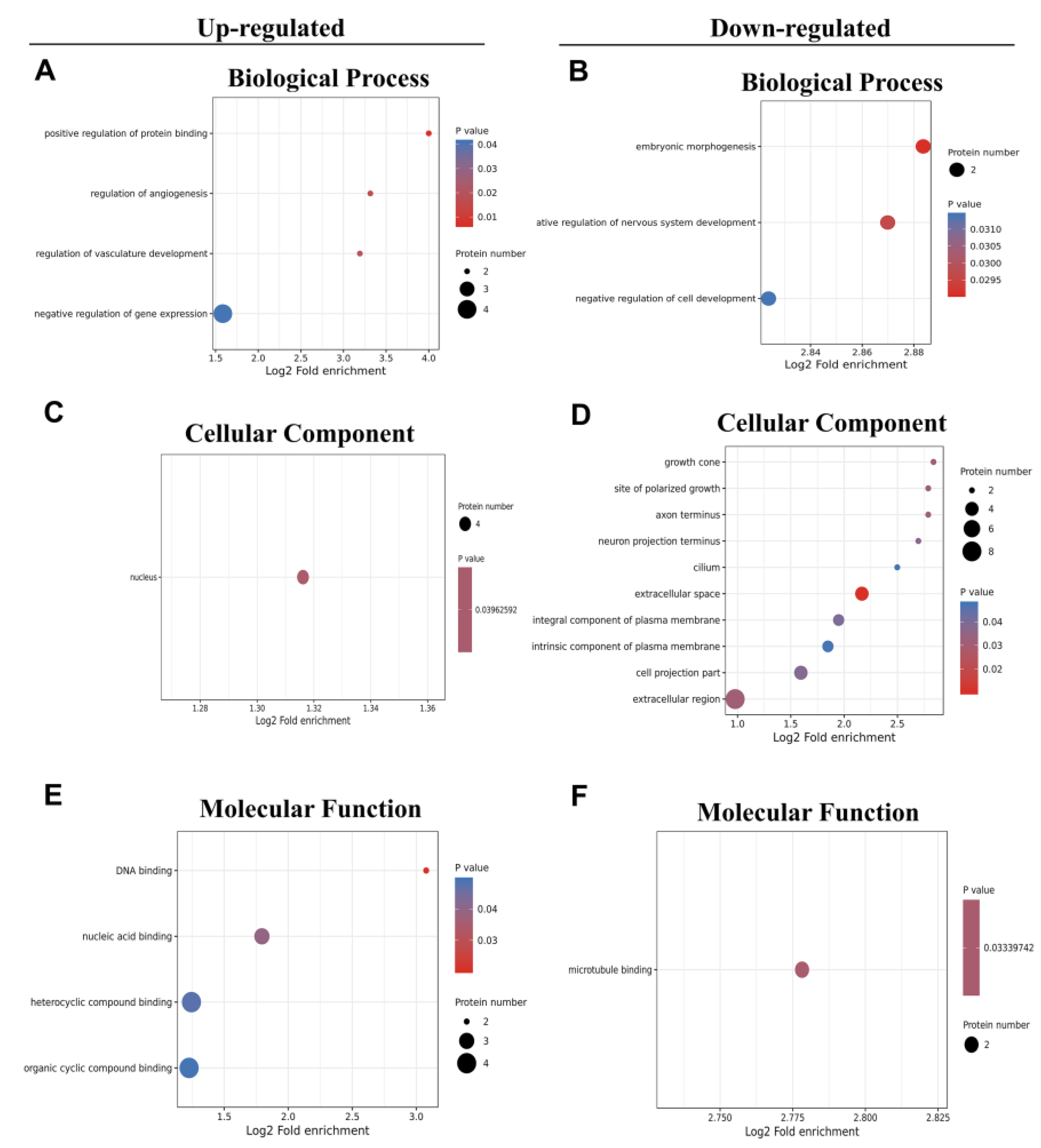

2.3. GO Analysis of DEPs

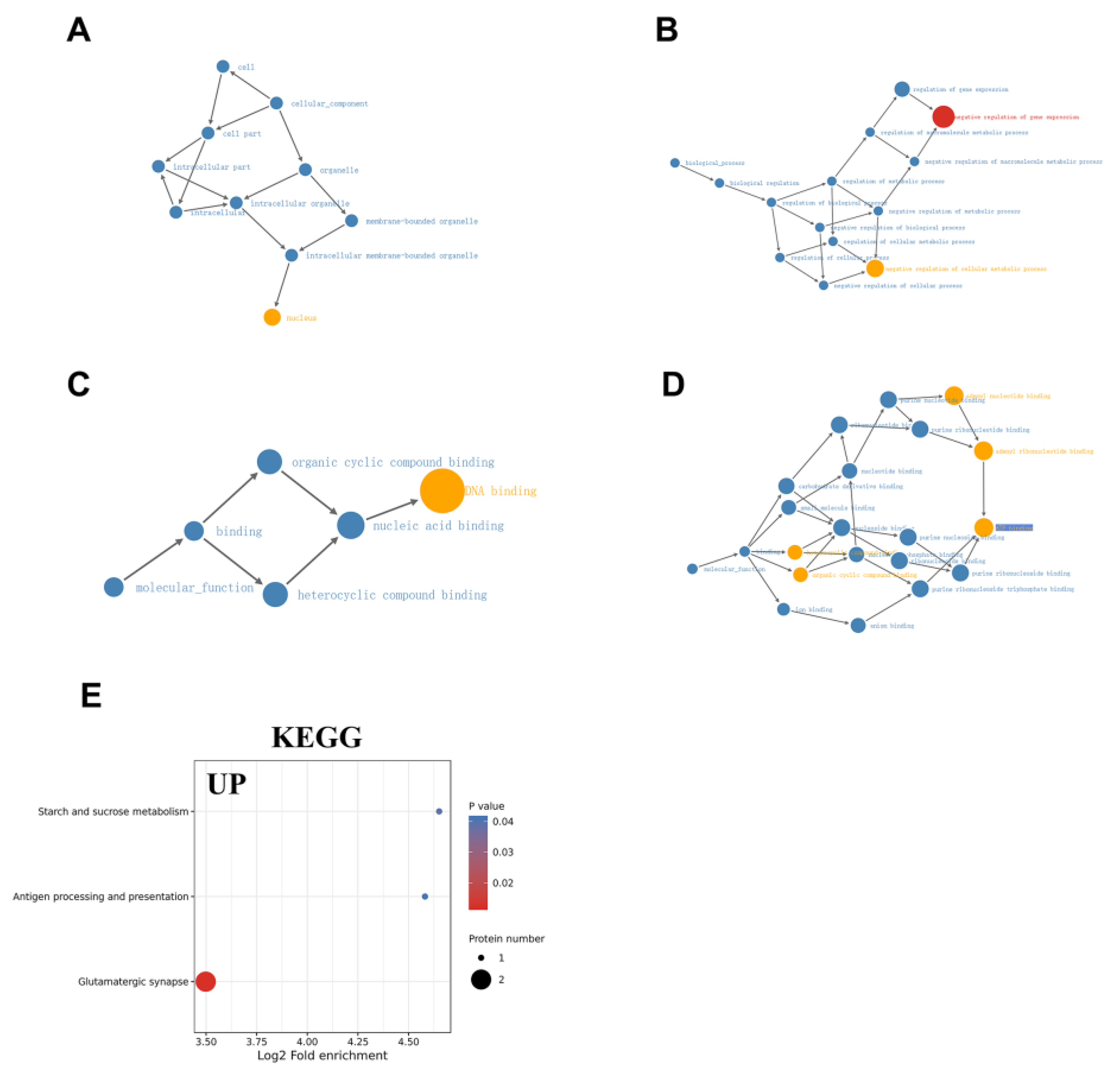

2.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of DEPs

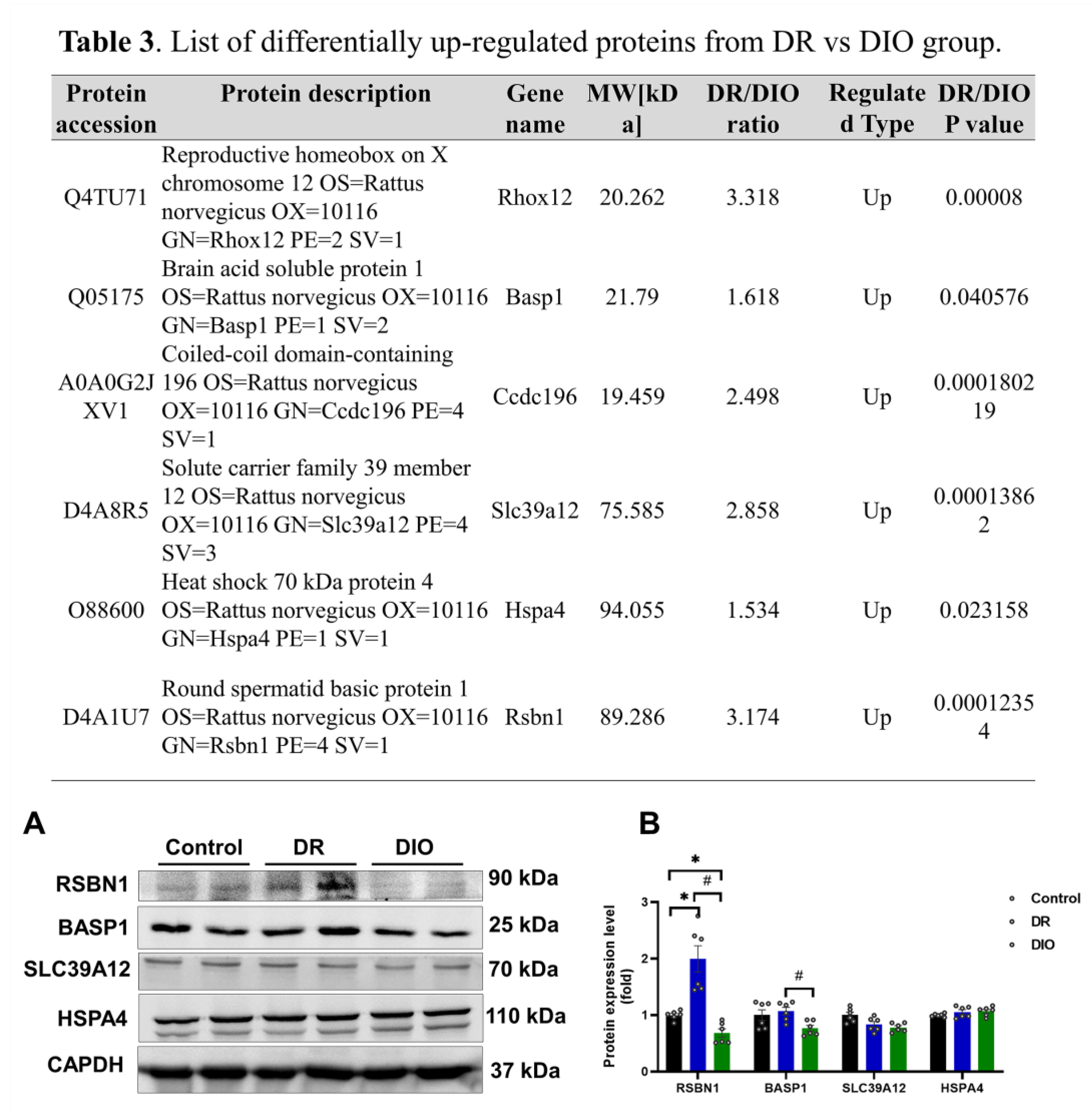

2.5. Analysis of Upregulated Proteins in Hypothalamus of DIO and DR Rats

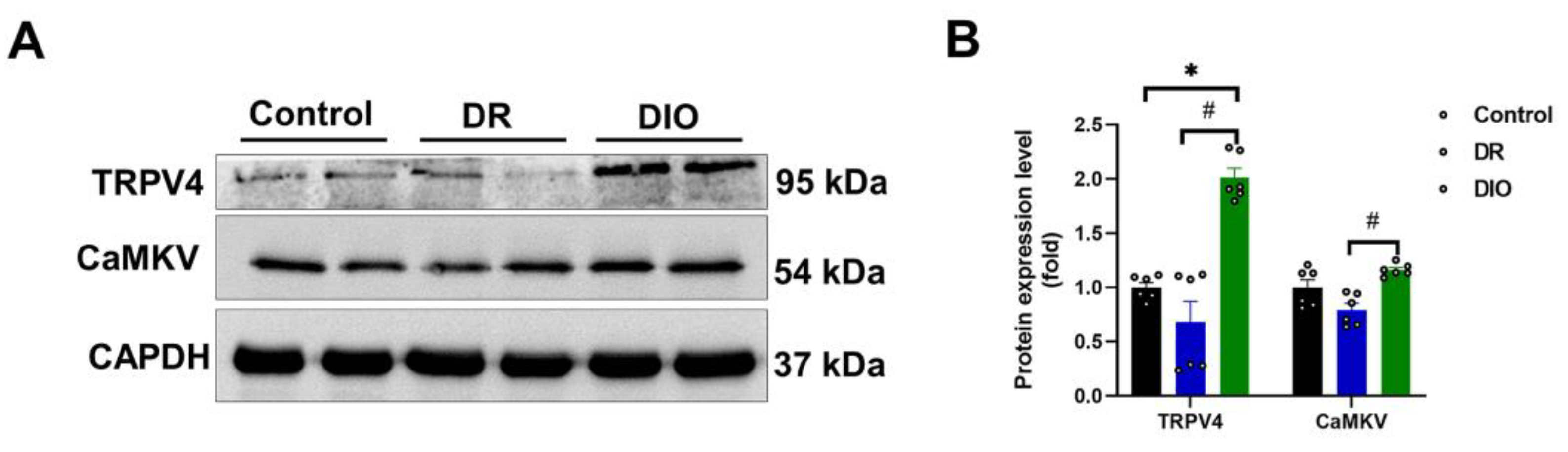

2.6. Analysis of Downregulated Proteins in Hypothalamus of DIO and DR Rats

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Body Mass Analysis

4.3. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

4.4. Blood Lipid Analysis

4.5. Protein Extraction and Proteomics Sample Preparation

4.6. TMT Labeling

4.7. HPLC Fractionation

4.8. Liquid Phase Enzyme Analyzer Using LC-MC/MC Analysis

4.9. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.10. Western Blotting Analysis

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIO | diet-induced obesity |

| DR | diet-induced obesity resistance |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| TG | triglyceride |

| HDL-C | high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| CFD | chow-fat diet |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| HE | hematoxylin-eosin |

| HPLC | reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| HSPA4 | Heat Shock Protein A Family 4 |

| BASP1 | Brain acid soluble protein 1 |

| TRPV4 | transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 |

| TMT | Tandem Mass tag |

| DEPs | differentially expressed proteins |

| TEAB | triethylammonium bicarbonate |

| SD | Sprague-Dawley |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| GUCA1A | guanylate cyclase activator 1A |

| SLC39A12 | solute carrier family 39-member 12 |

| ABLIM2 | actin-binding LIM protein 2 |

| ZMYM3 | Zinc finger MYM-type-containing 3 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene fluoride |

References

- Mouton, A.J.; Li, X.; Hall, M.E.; Hall, J.E. Obesity, Hypertension, and Cardiac Dysfunction: Novel Roles of Immunometabolism in Macrophage Activation and Inflammation. Circ Res 2020, 126, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, B. Humans against Obesity: Who Will Win? Adv Nutr 2019, 10, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, K.; Tang, X.; Chen, A. Differences in energy metabolism and mitochondrial redox status account for the differences in propensity for developing obesity in rats fed on high-fat diet. Food Sci Nutr 2021, 9, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poret, J.M.; Souza-Smith, F.; Marcell, S.J.; Gaudet, D.A.; Tzeng, T.H.; Braymer, H.D.; Harrison-Bernard, L.M.; Primeaux, S.D. High fat diet consumption differentially affects adipose tissue inflammation and adipocyte size in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats. Int J Obes (Lond) 2018, 42, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Duan, M.; Lin, J.; Wang, G.; Gao, H.; Yan, M.; Chen, L.; He, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, F.; et al. LncRNA and mRNA expression profiles in brown adipose tissue of obesity-prone and obesity-resistant mice. iScience 2022, 25, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.M.; Yang, H.; Tian, D.R.; Cai, Y.; Wei, Z.N.; Wang, F.; Yu, A.; Han, J.S. Proteomic analysis of rat hypothalamus revealed the role of ubiquitin-proteasome system in the genesis of DR or DIO. Neurochem Res 2011, 36, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Domínguez, Á.; Millán-Martínez, M.; Domínguez-Riscart, J.; Mateos, R.M.; Lechuga-Sancho, A.M.; González-Domínguez, R. Altered Metal Homeostasis Associates with Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Impaired Glucose Metabolism, and Dyslipidemia in the Crosstalk between Childhood Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, B.; Feng, S.; Zhu, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H. Comparison of visceral fat lipolysis adaptation to high-intensity interval training in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, M.-E.; Tchernof, A.; Després, J.-P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation Research 2020, 126, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, H.-W.; Cerbone, M.; Dattani, M.T. Appetite- and Weight-Regulating Neuroendocrine Circuitry in Hypothalamic Obesity. Endocrine Reviews 2024, 45, 309–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornier, M.A.; McFadden, K.L.; Thomas, E.A.; Bechtell, J.L.; Bessesen, D.H.; Tregellas, J.R. Propensity to obesity impacts the neuronal response to energy imbalance. Front Behav Neurosci 2015, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.F.; Solon, C.; Nascimento, L.F.; De-Lima-Junior, J.C.; Nogueira, G.; Moura, R.; Rocha, G.Z.; Fioravante, M.; Bobbo, V.; Morari, J.; et al. Defective regulation of POMC precedes hypothalamic inflammation in diet-induced obesity. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos-Jankiewicz, A.; Guzman-Quevedo, O.; Fenelon, V.S.; Zizzari, P.; Quarta, C.; Bellocchio, L.; Tailleux, A.; Charton, J.; Fernandois, D.; Henricsson, M.; et al. Hypothalamic bile acid-TGR5 signaling protects from obesity. Cell metabolism 2021, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Fang, T.; Chen, H. Zinc and Central Nervous System Disorders. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, P.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liang, H.; Wang, H.; Tian, D. Upregulation of hypothalamic TRPV4 via S100a4/AMPKalpha signaling pathway promotes the development of diet-induced obesity. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2024, 1870, 166883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, G.; Gautier, E.L.; Clement, K. Adipose Tissue Fibrosis in Obesity: Etiology and Challenges. Annu Rev Physiol 2022, 84, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, E.N. Thyroid hormone and obesity. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity 2012, 19, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Moro Chao, D.; Kirchner, M.K.; Pham, C.; Foppen, E.; Denis, R.G.P.; Castel, J.; Morel, C.; Montalban, E.; Hassouna, R.; Bui, L.C.; et al. Hypothalamic astrocytes control systemic glucose metabolism and energy balance. Cell metabolism 2022, 34, 1532–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.C.; Valencia-Vasquez, A.; Garcia, A.M. Role of TRPV4 Channel in Human White Adipocytes Metabolic Activity. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2021, 36, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Ding, Y.; Li, Q.; Shi, R.; He, Y. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channels as therapeutic targets in diabetes and diabetes-related complications. J Diabetes Investig 2020, 11, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, D.; Wen, X.; Tang, X.; Qi, D.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, W.; Zhu, T. Adipose-derived exosomes protect the pulmonary endothelial barrier in ventilator-induced lung injury by inhibiting the TRPV4/Ca(2+) signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2020, 318, L723–L741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusudo, T.; Wang, Z.; Mizuno, A.; Suzuki, M.; Yamashita, H. TRPV4 deficiency increases skeletal muscle metabolic capacity and resistance against diet-induced obesity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012, 112, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Kleiner, S.; Wu, J.; Sah, R.; Gupta, R.K.; Banks, A.S.; Cohen, P.; Khandekar, M.J.; Bostrom, P.; Mepani, R.J.; et al. TRPV4 is a regulator of adipose oxidative metabolism, inflammation, and energy homeostasis. Cell 2012, 151, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Conor, C.J.; Griffin, T.M.; Liedtke, W.; Guilak, F. Increased susceptibility of Trpv4-deficient mice to obesity and obesity-induced osteoarthritis with very high-fat diet. Ann Rheum Dis 2013, 72, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; Xi, P.; Tian, D. TRPV4 in adipose tissue ameliorates diet-induced obesity by promoting white adipocyte browning. Translational Research 2024, 266, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wong, C.C.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Plattner, F.; Lai, K.O.; Ip, N.Y. The pseudokinase CaMKv is required for the activity-dependent maintenance of dendritic spines. Nature communications 2016, 7, 13282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozolewski, P.; Jeziorek, M.; Schuster, C.M.; Bading, H.; Frost, B.; Dobrowolski, R. The role of nuclear Ca2+ in maintaining neuronal homeostasis and brain health. Journal of Cell Science 2021, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, S.; Feijó, G.d.S.; Neto, J.; Jantsch, J.; Braga, M.F.; Castro, L.F.d.S.; Giovenardi, M.; Porawski, M.; Guedes, R.P. Zinc Supplementation Decreases Obesity-Related Neuroinflammation and Improves Metabolic Function and Memory in Rats. Obesity 2020, 29, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Fan, C.; Ding, C.; Xu, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xing, T. Loss of Slc39a12 in hippocampal neurons is responsible for anxiety-like behavior caused by temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, D.N.; Strong, M.D.; Chambers, E.; Hart, M.D.; Bettaieb, A.; Clarke, S.L.; Smith, B.J.; Stoecker, B.J.; Lucas, E.A.; Lin, D.; et al. A role for zinc transporter gene SLC39A12 in the nervous system and beyond. Gene 2021, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarr, E.; Udawela, M.; Greenough, M.A.; Neo, J.; Suk Seo, M.; Money, T.T.; Upadhyay, A.; Bush, A.I.; Everall, I.P.; Thomas, E.A.; et al. Increased cortical expression of the zinc transporter SLC39A12 suggests a breakdown in zinc cellular homeostasis as part of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. npj Schizophrenia 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-E.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, K.-A. Rhoxin mammalian reproduction and development. Clinical and Experimental Reproductive Medicine 2013, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganas, L.N.; Durá, I.; Osenberg, S.; Semerci, F.; Tosun, M.; Mishra, R.; Parkitny, L.; Encinas, J.M.; Maletic-Savatic, M. BASP1 labels neural stem cells in the neurogenic niches of mammalian brain. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Ming, H. HSPA4 regulated glioma progression via activation of AKT signaling pathway. Biochem Cell Biol 2024, 102, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, L.; Sun, C. SIRT1 attenuates neuroinflammation by deacetylating HSPA4 in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2022, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, P.; Du, J.; Liang, H.; Han, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; He, L.; Wang, Q.; Ge, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Intraventricular Injection of LKB1 Inhibits the Formation of Diet-Induced Obesity in Rats by Activating the AMPK-POMC Neurons-Sympathetic Nervous System Axis. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 2018, 47, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Increased proteins | Gene name | Accession | Fold increase | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive homeobox on X chromosome 12 | Rhox12 | A6JMJ3 | 3.318 | 7.8339E-05 |

| Lysine-specific demethylase 9 | Rsbn1 | D4A1U7 | 3.174 | 0.00012354 |

| Solute carrier family 39-member 12 | Slc39a12 | D4A8R5 | 2.858 | 0.00013862 |

| Coiled-coil domain-containing 196 | Ccdc196 | D4A4F0 | 2.498 | 0.00018022 |

| Brain acid soluble protein 1 | Basp1 | Q05175 | 1.618 | 0.040576 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 4 | Hspa4 | O88600 | 1.534 | 0.023158 |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L28 | Mrp128 | D3ZJY1 | 1.308 | 0.0061432 |

| Actin-binding LIM protein 2 | Ablim2 | A0A0G2JXC7 | 1.284 | 0.048341 |

| Metabotropic glutamate receptor 8 | Grm8 | M0RBY2 | 1.264 | 0.048403 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G | Gng8 | P63077 | 1.259 | 0.048143 |

| Bublin coiled coil protein | Bbln | D3ZBT2 | 1.249 | 0.039317 |

| Leucine-rich repeat flightless-interacting protein 2 | Lrrfip2 | Q4V7E8 | 1.238 | 0.033423 |

| COMM domain containing 8 | Commd8 | B0K015 | 1.217 | 0.0074358 |

| Glucan (1,4-alpha-), branching enzyme 1 (Fragment) | Gbel | A0A096MJY6 | 1.213 | 0.031024 |

| Decreased proteins | Gene name | Accession | Fold increase | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaM kinase-like vesicle-associated protein | Camkv | A0A0G2K1R5 | 0.335 | 0.04622 |

| Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4 | Trpv4 | Q9ERZ8 | 0.421 | 0.044919 |

| Kirre-like nephrin family adhesion molecule 3 | Kirrel3 | A0A0G2K5L4 | 0.668 | 0.0119211 |

| KRIT1, ankyrin repeat-containing | Krit1 | G3V8Z6 | 0.71 | 0.0063187 |

| Endosome-lysosome associated apoptosis and autophagy regulator 1 | Elapor1 | F1MAB2 | 0.723 | 0.0057844 |

| Zinc finger MYM-type-containing 3 (Fragment) | Zmym3 | A0A096MK81 | 0.742 | 0.029479 |

| Cathepsin F | Ctsf | Q499S6 | 0.746 | 0.0145954 |

| AP complex subunit sigma | Ap1s1 | B5DFI3 | 0.746 | 0.0029365 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, G | Ptprg | A0A0G2K561 | 0.751 | 0.0060037 |

| EKC/KEOPS complex subunit Tprkb | Tprkb | Q5PQR8 | 0.769 | 0.024203 |

| EBP-like OS=Rattus norvegicus | Ebpl | D3ZXC8 | 0.774 | 0.0131801 |

| Guanylate cyclase activator 1A | Guca1a | D3ZII9 | 0.775 | 0.0118963 |

| Selenoprotein P | Selenop | P25236 | 0.78 | 0.044981 |

| Homeobox protein engrailed-like | En1 | A0A0G2JT82 | 0.788 | 0.040136 |

| Contactin-5 | Cntn5 | F1M173 | 0.79 | 0.048221 |

| N-acetyltransferase 8 (GCN5-related) family member 1 | Nat8f1 | V9GZ80 | 0.806 | 0.0086754 |

| Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein FLRT3 | Flrt3 | B1H234 | 0.812 | 0.039741 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).