Introduction

Menopause, a significant milestone in a woman’s health, is defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity, typically occurring between the ages of 45 and 55 years [

1]. Although it is a universal biological process, yet the experience of menopause varies considerably across different cultures and societies. Studies suggest that in Pakistan many women reach menopause by their mid-40s, with the mean age reported as 47 years [

2]. This natural transition is often accompanied by an array of symptoms including vasomotor disturbances, sleep problems, mood fluctuations, musculoskeletal pain, urogenital complaints, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction and cognitive difficulties. These symptoms individually or collectively, can contribute to a notable reduction in a woman’s overall quality of life [

3].

Women’s experiences of menopause unfold across different stages, from the perimenopause to the post menopause. They are not only biological but also deeply psychological [

4].

While most women in Pakistan experience menopause through natural ovarian ageing, menopause from surgical interventions is also prevalent and contribute significantly to the symptom burden [

5]. Medical and premature menopause are equally important considerations that cannot be overlooked; however, data from Pakistan are limited, and no exact prevalence figures could be identified in the available literature.

Yet psychological well-being during this stage remains under recognized in clinical practice, and evidence from Pakistan indicates that menopausal women often experience considerable anxiety and depression, underscoring the need for greater clinical focus and culturally appropriate mental health interventions [

6].

However, most of the existing literature on menopause originates from Western contexts, where increasing emphasis has been placed on symptom management, hormone replacement therapy, and workplace support [

7,

8].

In contrast, women in Pakistan often face distinct challenges particularly in the professional life, including subtle age-related discrimination and pressures to maintain professional appearance, as rising awareness has only partially translated into adequate recognition in healthcare services or workplace policies [

9].

Moreover, even in the younger women, the household responsibilities, entrenched social taboos and cultural constraints, acts as barriers to normalising sexual and reproductive health, thereby limiting open dialogue and access to care [

10].

Within South Asia, women have limited use of healthcare services for their menopausal symptoms, and rely heavily on informal or traditional coping strategies [

11,

12].

In Pakistan, awareness of menopause remains still limited and cultural sensitivities frequently discourage open discussions on reproductive health issues [

13].

Existing literature has largely focused on symptom prevalence, while the psychological dimensions of menopause, women’s coping mechanisms and awareness gaps that perpetuates silence remain underexplored [

2,

5].

As women’s participation in the global workforce continues to expand, increasing attention has been given to the need for workplace policies that acknowledge and accommodate women’s midlife health concerns [

8]. Despite this international momentum, there is a striking lack of empirical data and policy discourse on workplace support for women in midlife within Pakistan.

This gap highlights the need for a qualitative inquiry that captures the psychological landscapes of menopause while exploring coping strategies and awareness gaps among them. The Pakistani chapter of MARIE-WP2a was developed with this purpose in mind. By foregrounding women’s voices, the study seeks to provide insights that are indispensable for designing responsive health care interventions and shaping policies that can better support women across all stages of menopause. Ultimately this study contributes to breaking the silence surrounding menopause in Pakistan, emphasizing the importance of psychological well-being during this transition.

Methods

Participants and Setting

This qualitative study (MARIE- PAKISTAN arm) is part of a larger mixed method study (MARIE WP2A), designed to explore the physical and psychological landscape, coping behaviours, and availability of social support to menopausal Pakistani women, guided by the GD and PP equity-oriented framework to identify individual, community, health system, and policy-level determinants of menopause experience [

14]. Semi-structured, face to face, in-depth interviews were conducted from March to May 2024, involving peri-menopausal, surgical menopausal or post-menopausal women, residing in the urban and peri-urban settings of Peshawar, Pakistan. Participants were purposively recruited through community networks, health facilities, and social contact to ensure diversity in socio-economic status, education, and marital background. These interviews were guided by a pre-designed topic guide that included psychological symptoms, physical symptoms, coping strategies, social support during menopause, health care engagements and the knowledge about work-place policies. Each interview lasted between 30 to 60 minutes, in their native language (Pashto or Urdu) and was audio-recorded with consent which then were transcribed and translated into English by bilingual researchers.

This approach allowed for the collection of detailed narratives and insights about the lived experiences of menopause in a comfortable environment suitable for discussing this sensitive topic, capturing both structured and emergent themes. The overarching questions asked during the interview were:

What is your experience of menopause? (Physical and psychological symptoms)

How have you been coping with these symptoms?

Did you take any help from health care professional for these symptoms? If no, what was the reason?

How was the support from family and friends during this time?

Do you know of any work place policies for menopausal women?

Data Analysis

The transcripts were reviewed for accuracy, and de-identified. Data was analysed using thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework: (a) familiarisation with data, (b) generating initial codes, (c) searching for themes, (d) reviewing themes, (e) defining and naming themes, and (f) producing the report [

15]. Coding was done manually by two researchers independently, followed by comparison and reconciliation of themes to ensure rigour. Verbatim quotes were used to support thematic findings.

Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from Institutional Review Board of Prime foundation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study, with pseudonyms used in transcript. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences.

RESULTS

Demographics of Interviewees

A total of 20 postmenopausal and peri-menopausal Pakistani women, aged between 45 and 68 years, were interviewed. Participants came from various backgrounds, including healthcare professionals, teachers, and homemakers. Time since the peri-menopause started, varied from 3 months to over 20 years.

Thematic Analysis

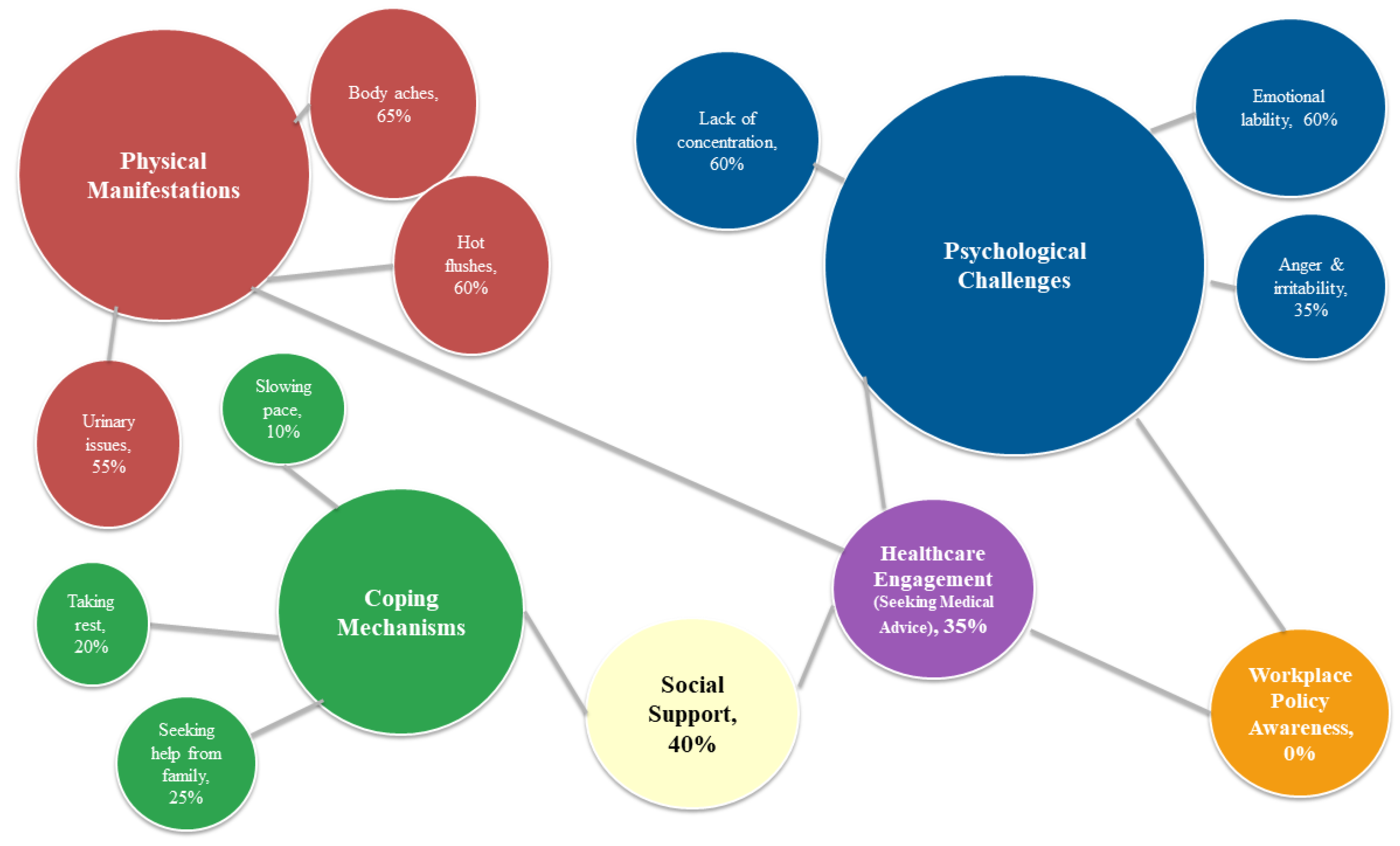

The following six themes emerged during the qualitative interview (

Table 1).

Theme 1: Physical Manifestation-The Everyday Challenge

All participants (n=20, 100%) reported experiencing physical symptom associated with menopause as mentioned in

Table 1. The majority of participants (n=13, 65%) reported experiencing body aches, predominantly localized to the lower back and knees. However, a few women stated they had not noticed any musculoskeletal symptoms associated with menopause.

“I experience pain in my back especially the lower part.” (P3)

“I have severe body aches and feel like each joint of my body is painful.” (P7)

“I have started having painful knees.” (P14)

“I do not experience back ache or any sort of pain.” (P9)

More than half of the participants (n=12, 60%) reported experiencing hot flushes, with the severity ranging from mild to intense episodes.

“I feel a wave of heat in my body (Garma lamba). It’s more pronounced at night. It makes me feel as if I have fever” (P2)

“I have had very bad hot flushes, so severe that I would rush to my room to turn on the fan even in winters. At night, I would sleep next to the wall so I could touch it during a hot flush because the wall felt cool” (P8)

“It is strange to me because I didn’t experience any hot flushes like my friends often complained about” (P20)

Urinary issues, primarily urgency and dribbling, were reported by over half of the participants (n=11, 55%), while others did not experience these concerns.

“The frequency of my urination has increased, and it dribbles before I can reach the toilet.” (P1)

“I feel the need to urinate again just a few minutes after going, and I experience urine dribbling when I cough” (P18)

A subset of participants (n=5, 25%) experienced palpitations, whereas the majority did not report this symptom.

“I have started having these episodes where I can feel my heart pounding and sinking (Zra me dobegee), and it is usually at night and is associated with the hot flushes.” (P2)

“I have started experiencing palpitations recently” (P9)

Regarding sexual discomfort, only 15% (n=3) openly reported issues, while others were unmarried, widowed, or preferred not to answer. A few did not identify any difficulty, but some participants mention decreased frequency due to pain during intimacy.

“Because of the pain, the frequency of our intimacy has decreased.” (P18)

“I have started experiencing problems in my sexual life, but I would rather not go into details” (P12)

Theme 2: Psychological Challenges: Navigating Emotional Shifts

Majority of the women reported psychological disturbances as detailed in Table 2. Most participants described experiencing emotional lability (n=12, 60%) manifesting as mood swings, irritability, and episodes of sadness.

“Even small inconveniences make me feel sad” (P1)

“At times, I find myself unusually irritable during conversations. I feel an impulse to react aggressively, like I would want to slap the other person” (P3)

“I often feel low in mood and have a persistent sense of sadness.” (P11)

“I have episodes of prolonged crying... I would just want to leave the house and escape everything around me.” (P13)

Lack of concentration was also reported by a number of respondents (n=12, 60%), affecting both daily functioning and religious practices.

“I struggle to recall short term details, such as where I have placed a certain item” (P2)

“While reciting holy verses during my prayers, I would suddenly lose track of what I was reciting, as if my mind goes completely blank.” (P6)

“I will open my laptop and then would completely forget what I intended to do” (P9)

“I would walk into the kitchen, open the fridge, and then completely forget why I did so in the first place.” (P15)

Anger issues were reported by a subset of participants (n=7, 35%), and was noted to occasionally affect interpersonal relationships.

“My tolerance has decreased, and I get angry more quickly than I used to be.” (P17)

“I find myself now becoming easily irritated and angry, often leading to arguments with my husband over minor issues.” (P18)

When asked about sleep disturbances, only a small proportion of participants (n=3, 15%) reported difficulties with sleep initiation and maintenance, while the majority did not experience any such problems

“My overall sleep duration has decreased and there are nights where I find it difficult falling asleep” (P5)

“I would wake up in the middle of the night and then find it difficult to fall back asleep afterwards” (P18)

Theme 3: Coping Mechanisms in Response to Menopausal Challenges

In discussing coping with menopausal challenges, majority of participants (n=12, 60%) indicated that menopause had impacted their capacity to manage daily activities. Reported coping strategies included seeking help from family (n=5, 25%), taking rest (n=4, 20%), slowing their pace (n=2, 10%), and using memory aids (n=1, 5%).

“I find it hard to manage responsibilities alone now, so I involve my daughter in my tasks” (P4)

“Since I get distracted and bored quickly with things I used to enjoy, I involve my son to keep me engaged” (P5)

“I find myself getting tired more quickly, so I take breaks in between and lay down” (P3)

“I tire easily now, so I need to take frequent rests as I go about my chores” (P7)

“I am not able to finish my work as fast as I used to, so I go slowly now” (P2)

“I have started writing things down in different colours as a memory aid - it makes it easier to recall tasks” (P9)

Theme 4: “Lean on Me”: Social Support in Menopause

In exploring the role of social support, fewer than half of the participants (n=8, 40%) described receiving meaningful assistance from family, friends and colleagues during this transition. While some shared stories of supportive workplaces, others felt invisible and misunderstood within their own families. For many (n=12, 60%), the menopausal journey was one they felt they had to navigate alone.

“My colleagues have been very considerate and have provided me with full support in the workplace”. (P3)

“My work colleagues are mostly female, and they are very aware of the fact that this phase is very sensitive and hence I feel very supported”. (P9)

“I don’t find my work environment very supportive. Everyone still expects me to work at the same level as before”. (P4)

“I don’t think my husband has been very supportive during this phase. It is important for a spouse to understand the changes happening in your body and how to support you during this difficult time”. (P5)

Theme 5: Health Care Engagement amid Transition

Participants were asked whether they sought help from their doctors regarding menopause. Only a minority (n=7, 35%) reported seeking medical advice, while others accepted menopause as a natural process and did not consult a health care provider. Among those prescribed HRT, some declined treatment, while others relied on traditional advice, or managed their symptoms independently.

“My gynaecologist advised me to take HRT, but I chose not to as I was worried about the side effects. Having worked in a gynaecology unit, I was particularly aware of the potential risks, which made me hesitant.” (P3)

“I have never consulted any one for it as I felt that this is a normal part of the aging process” (P4)

“When my cycles became irregular, I consulted my gynaecologist. She did an ultrasound and explained that what I am experiencing is a normal part of aging, and did not prescribe any medications” (P6)

“I did not consult any one as I was rather happy I stopped having the menses (Jamay may khatmay shway)”. (P7)

“I consulted my gynaecologist twice after my womb was removed, as I started facing a lot of physical issues. She only prescribed calcium supplements which did not help a lot. She explained that rest of the symptoms will improve with time” (P8)

“Although I was prescribed HRT, I chose not to use it as my sister-in-law was diagnosed with breast cancer, so I got scared and never used the treatment”. (P20)

Theme 6: Policy Awareness in the Workplace During Menopause

None of the participants reported of any workplace policies addressing menopause; however, all emphasized the need for such policies to support women during this transition. (

Figure 1).

“I do not know of any workplace policy for menopausal women, but I would want the government to look into the matter and devise such policies”. (P2)

“I don’t know of any workplace policies supporting menopausal women but I wish the authorities would implement some”. (P6)

Figure 1 is a thematic bubble map illustrates the six core themes and related sub-themes emerging from qualitative interviews with Pakistani women about their menopausal experiences. Larger bubbles represent dominant themes, while smaller surrounding bubbles depict related sub-themes. Connecting lines indicate interrelationships between themes, and how these interact to shape women’s lived experiences of menopause.

Discussion

This qualitative study provides a detailed exploration of menopausal experiences among Pakistani women, particularly focusing on the psychological landscapes of menopause, the coping strategies and awareness gaps among them. Our findings suggest that menopause is experienced not merely as a biological transition but as a complex psychosocial event shaped by cultural norms, familial expectations, systemic gaps in healthcare and workplace support.

The findings of our study confirm that the physical manifestations of menopause constitute the most prominent and often distressing aspect of women lived experiences. Musculoskeletal pain was the most frequently reported symptom. This aligns with evidence from Pakistan and other South Asian settings where joint and body aches are among the most frequently cited menopausal complaints [

16]. These finding are in line with the global studies which also recognizes musculoskeletal discomfort as a common midlife symptom, often attributed to declining estrogen levels and age-related changes [

17]. Interestingly, some women reported no such symptoms, reflecting heterogeneity in symptom perception and possibly normalization of age-related discomfort in certain contexts.

Vasomotor symptoms, especially hot flushes, were reported by more than half of the participants. The prevalence of vasomotor symptoms observed in this study aligns with a Pakistani review by Mallhi et al [

18]. Compared with Western populations, hot flushes and night sweats are often considered the hallmark of menopause [

19]. The relatively lower reporting in South Asia may be due to cultural differences in expression, dietary or lifestyle factors, or under-recognition of symptoms. However, a few participants denied experiencing hot flushes, suggesting variability in both symptom expression and thresholds for discomfort.

In our population, urinary symptoms were described by over half of the women, consistent with findings from regional studies which highlight urogenital complaints as one of the most prevalent yet under-discussed aspects of menopause [

20]. Although these symptoms, can greatly affect women’s daily lives, they often go unspoken and untreated, because of embarrassment, cultural taboos and limited access to specialized care.

Sexual discomfort was reported only by a minority of participants, largely due to cultural sensitivities, or reluctance to discuss intimate concerns. Our findings are in line with a study from Iran which reports similar pattern [

21]. In contrast, studies from the Western societies more frequently document vaginal dryness and dyspareunia as core menopausal concerns, reflecting greater openness in discussing sexual health [

22].

Overall, these findings suggest that although the physical manifestations of menopause are like what is reported worldwide, their expression and reporting are influenced by socio-cultural norms and gaps in the healthcare system.

This study underscores the psychological burden of menopause, with emotional instability, irritability, and concentration difficulties emerging as prominent concerns. These findings are broadly consistent with recent studies in both Pakistan and internationally. For instance, a cross-sectional study from Pakistan reported elevated levels of anxiety, low mood, and exhaustion among postmenopausal women, indicating that mood symptoms are common psychological challenges in this population [

23].

An interesting finding of our study was that concentration difficulties sometimes disrupted even religious practices, highlighting how cognitive lapses can interfere with aspects of daily life that women value deeply. This is supported by studies from the international literature which highlights that women’s experience of difficulties with concentration during menopause, often described as, brain fog, extends beyond simple memory lapses, affecting a wide range of cognitive abilities [

24].

Sleep issues were reported only by a small subset of women in our population, which contrasts with a review from the Western literature, which reports frequent nighttime awakenings, difficulty maintaining sleep, and increased wakefulness after sleep onset. This difference may reflect under-reporting, cultural differences in noticing sleep problems, or possibly that psychological symptoms other than sleep are more salient in this sample [

25].

The findings of our study indicate that women predominantly relied on family support, rest, slowing their pace, and using simple memory aids to cope with menopausal challenges. This highlights how women from this population rely on practical, culturally shaped ways of coping with challenges associated with menopause. These finding are in line with a study from Iran, where women relied heavily on social support and practical lifestyle adjustments [

26].

Our findings highlight that social support during menopause was perceived as limited by most participants and for many, menopause was experienced as a solitary journey. These findings resonate with literature from South Asia, where limited family and community awareness of menopause has been shown to contribute to feelings of neglect and isolation [

27]. By contrast, recent international studies emphasize the positive role of social networks, peer support groups, and workplace accommodations in buffering psychological distress during menopause. In Western contexts, structured interventions such as menopause education programs are increasingly recognized as valuable in enhancing women’s coping and well-being [

28]. However, even in these contexts, women may face stigma and lack of understanding, especially in male-dominated workplaces.

Our findings highlight limited engagement with health care services during the menopausal transition, with only a minority of participants seeking medical advice.

These findings are in line with a study from India, where the symptom prevalence was high, most women did not seek formal health care [

29]. A study conducted in 2023 in the UK found that while awareness of menopause management is increasing, many women remain hesitant about HRT due to safety concerns [

30]. This may be attributed to cultural perceptions, health literacy, and differences in health system responsiveness.

Our findings indicate a complete lack of awareness about workplace policies on menopause, despite participants strongly endorsing their need. This gap reflects limited institutional recognition of midlife women’s health and the absence of occupational health strategies to support productivity and well-being. These findings resonate with other South Asian literature, where menopause remains largely absent from workplace health agendas, underscoring the need for structured occupational strategies to support women during this transition [

31]. By contrast, in high-income countries workplace interventions such as flexible work adjustments, and peer-support groups have improved well-being and reduced symptom burden. Yet stigma persists and policy implementation remains inconsistent [

32].

Limitations

The findings of this study offer valuable insights on the menopausal experience among Pakistani women residing primarily within urban and semi-urban settings. We recognise these insights may differ within rural and semi-rural principalities. As the study relied on self-reported narratives, the possibility of recall bias cannot be entirely ruled out.

Future Directions

These findings highlight the need to integrate menopausal care into national health agendas through the development of culturally appropriate guidelines for delivery of clinical care. Establishing dedicated menopausal clinics at both primary and secondary levels, with affordable access to HRT, mental health and wellbeing services would provide vital options to better manage menopausal symptoms. Mandatory training for primary care providers should be prioritised to improve recognition and management of menopausal health. In parallel, community-based awareness campaigns must be launched to break taboos and normalise discussion of menopause. Additionally, workplace support policies recognising menopause as a life-stage that may require additional support could ensure staff retention and improved long term health outcomes.

Conclusion

Menopause among Pakistani women is deeply shaped by psychological, cultural, and systemic factors. While women demonstrate resilience through informal coping strategies, the absence of formal recognition in healthcare and policy frameworks exacerbates distress and perpetuates silence. Addressing these gaps through awareness, healthcare integration, and workplace policies is critical for improving quality of life during this natural life transition.

Author Contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. MI and RK submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study. RK collected data. RK and MI conducted the data analysis. RK and MI wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. MI edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund.

Ethics approval

Prime Foundation Pakistan Institutional Review Board (PRIME/IRB/2023-1044).

Consent to participate

Obtained.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

MARIE Consortium: Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dasanayaka, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Jeevan Dhanasiri, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Ganesh Dangal, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani and Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Chukwuemeka Chijindu Njoku, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumder, Donatella Fontana, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Chukwuemeka Chijindu Njoku.:

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- World Health Organization. Menopause [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/.

- Baig LA, Karim SA. Age at menopause, and knowledge of and attitudes to menopause, of women in Karachi, Pakistan. J Br Menopause Soc. 2006;12(2):71–4. [CrossRef]

- Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):760–70.

- Hu LY, Shen CC, Hung JH, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following symptomatic menopausal transition: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(6):e2800.

- Nusrat N, Nishat Z, Gulfareen H,et al. Knowledge, attitude and experience of menopause. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20(1):56–9.

- Qazi KF, Iqbal A, Panhwar MW, et al. Impact of menopause on psychological wellbeing of women in Pakistan. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2024;31(6):3461–8. [CrossRef]

- Verdonk P, de Rijk A, de Leeuw J, et al. Menopause and work: a narrative literature review. Work. 2022;73(3):813–25.

- Hardy C, Griffiths A, Hunter MS. What do working menopausal women want? A qualitative investigation into women’s experiences of working through the menopause. Maturitas. 2017;101:37–41.

- Tariq N, Shahid A, Malik AA, et al. Workplace challenges and their impact on quality of life among women in midlife and beyond. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2025;75(Suppl-5):S724–9. [CrossRef]

- Ali TS, Asif N, Adnan F, et al. Sexual and reproductive health in Pakistan: a qualitative exploratory study of gender roles, family planning and adolescent health in Chitral, Gilgit-Baltistan and Sindh. BMJ Public Health. 2025;3(1):e000870. [CrossRef]

- Zahan A, Sharma NK, Islam MN,et al. Menopausal symptoms and coping strategies among women of 40–60 years age group: a tertiary care hospital experience from Bangladesh. Community Based Med J. 2025;14(1):54–60.

- Singh N, Chouhan Y, Patel S. Treatment seeking behavior among post-menopausal women. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018;5(6):2444–8.

- Nasim A, Haq NU, Riaz S, et al. Assessment of knowledge and awareness regarding the postmenopausal syndrome in women aged above 30 years in Quetta, Pakistan. J South Asian Feder Menopause Soc. 2019;7(1):24–8. [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle G, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13:e196–8. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Saeed A, Khan A, Naz S, Butt S. Quality of life after menopause in Pakistani women. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2016;10(2):516–20.

- Wright VJ, Schwartzman J, Itinoche R, et al.The musculoskeletal syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2024;27(5):466–72. [CrossRef]

- Mallhi TH, Khan YH, Khan AH, et al. Managing hot flushes in menopausal women: a review. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28(6):460–5. [CrossRef]

- Freeman EW, Sherif K. Prevalence of hot flushes and night sweats around the world: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2007;10(3):197–214. [CrossRef]

- Yahya S, Rehan N. Age, pattern and symptoms of menopause among rural women of Lahore. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2002;14(1):9–12.

- Ghazanfarpour M, Moieni M, Montazeri A. Obstacles to the discussion of sexual problems in menopausal women: a qualitative study of healthcare providers. Climacteric. 2017;20(3):257–63.

- Kasano JP, Bui TH, Park IO, et al. Genitourinary syndrome in menopause: impact of vaginal symptoms on quality of life in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2023;26(2):165–73.

- Khurshid F, Chattha AN, Zain M, et al. A cross-sectional study to explore depression in postmenopausal women. J Shalamar Teach Med Univ. 2024;7(1):61–7. [CrossRef]

- Weber MT, Mapstone M, Henderson VW, et al. Brain fog in menopause: a health-care professional’s guide for decision-making and counseling on cognition. Menopause. 2025;32(5):505–11.

- Maki P, Panay N, Simon JA. Sleep disturbance associated with the menopause: frequent night-time awakenings, increased wakefulness after sleep onset, and links with mood and vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2024;31(8):724–33.

- Refaei M, Mardanpour S, Masoumi SZ,et al. Women’s experiences in the transition to menopause: a qualitative research. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):53.

- Zou P, Shao J, Luo Y, et al. Facilitators and barriers to healthy midlife transition among South Asian immigrant women in Canada: a qualitative exploration. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(2):182. [CrossRef]

- Geukes M, Verdonk P, Appelman Y, et al. Evaluation of a workplace educational intervention on menopause: a quasi-experimental study. Maturitas. 2023;174:48–56.

- Sundararajan M, Madhuvarshini S, Saravanan N. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and health-seeking behavior among school teachers in Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2023;10(3):1224–31.

- Barber K, Charles A. Barriers to accessing effective treatment and support for menopausal symptoms: a qualitative study capturing the behaviours, beliefs and experiences of key stakeholders. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:2971–98. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, M. Menopause in the workplace: challenges and solutions for health care and HR professionals. J South Asian Feder Obst Gynae. 2025;17(1):1–3.

- Rodrigo CH, Smith A, Ramlall S, et al. Effectiveness of workplace-based interventions to promote menopausal health and work outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:352.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).