Introduction

Perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause represent critical biological transitions in the reproductive life course of women, each associated with distinct physiological, psychological, and social changes [

1]. Perimenopause is the transitional phase preceding menopause, characterised by fluctuating hormone levels and irregular menstrual cycles [

2]. Menopause is defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation for twelve consecutive months, signalling the end of ovarian function, while post-menopause encompasses the years following this transition, often associated with continued symptomatology and long-term health implications such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease [

3,

4,

5]. These stages can occur naturally, as part of the ageing process, or be surgically induced, for instance through hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy, or medically induced via interventions such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone-suppressing treatments for conditions like breast cancer or endometriosis [

6,

7]. In Middle Eastern contexts, including Oman, these reproductive transitions are embedded within unique cultural, religious, and familial frameworks that shape symptom expression, care-seeking behaviours, and the interpretation of menopause [

8,

9]. The region’s social norms often emphasise modesty, family continuity, and caregiving roles for women, which can influence how menopause is discussed, understood, and treated. While biomedical definitions of menopause are universal, the lived experience is deeply influenced by local traditions, intergenerational dynamics, and sociopolitical factors that dictate access to healthcare and knowledge.

Oman has witnessed rapid demographic and epidemiolocal transitions in recent decades, with rising life expectancy and increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [

10]. Women in Oman and across the Gulf region now live substantially longer beyond reproductive age, creating new public health challenges related to menopause and ageing [

11,

12]. As per National Center for Statistics Information, Oman (NCSI), in 2025 estimated total population is 5.5million (2.49 Omanis and 2.12million expatriates). Total number of Omani women in 2024 was 1,483,057 making up nearly 49% of the Omani population and those above 50 years of age were 179,869 (12%) a figure projected to increase as the population continues to age [

12]. The majority of expatriate work force are males [

13]. The government and private sector have health care workers from multiple backgrounds especially from other South Asia, North Africa other Arabic countries. The majority are able to communicate in both languages. These diaspora populations will need physicians who are well versed in managing midlife health issues in a multicultural patient population. Despite these shifts, menopause remains largely under-researched and lacks public awareness campaigns in Oman. Health policies and clinical services prioritised major national programmes such as decreasing maternal and infant morbidity and mortality and increasing child immunization campaigns. Currently, there are limited policies and provisions for midlife women’s health beyond reproductive years. This leaves many women both Omani nationals and expatriates with limited support during a stage of life that significantly affects quality of life, productivity, and long-term health outcomes.

Rationale

There is an increasing need to better understand the menopausal experiences of women in Oman, considering both nationals and diverse expatriate populations. While global literature increasingly recognises menopause as a key public health issue, there remains a critical evidence gap in Middle Eastern contexts, where sociocultural norms, health system structures, and gendered expectations may produce unique health inequalities. The MARIE project aims to address these gaps by generating context-specific evidence on menopause, using qualitative methodologies to capture women’s lived experiences and identify barriers to equitable care. By applying the Delanerolle and Phiri Theory and Qualitative Framework [

14], this study situates menopause within interconnected domains of biological, psychological, sociocultural, and health system factors. Understanding how these factors interact in Oman is essential for informing culturally sensitive policies, improving healthcare services, and supporting women during perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause [

15,

16,

17]. This work represents a critical step towards integrating midlife women’s health into broader public health agendas and advancing gender equity in healthcare delivery in Oman and beyond.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This qualitative study was conducted as part of the MARIE (Menopause and Ageing Research in International Environments) project [

18], focusing on Work Package 2a (WP2a) in Oman. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with Omani women and expatriate women residing in Oman to explore their experiences of perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause. Recruitment occurred through community networks, healthcare facilities, and diaspora organisations. Participants included women across a range of menopausal stages, educational backgrounds, and employment statuses to ensure diversity of perspectives.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted in Arabic and English (n=26), depending on participant preference. Bilingual trained researchers facilitated the sessions, ensuring cultural sensitivity and confidentiality. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English where necessary. Field notes were taken to capture non-verbal cues and contextual factors influencing the interviews.

Analytic Approach

The analysis followed the Delanerolle and Phiri Theory and Qualitative Framework, which examines menopause through four interconnected domains:

Biological domain – physiological symptoms and bodily changes.

Psychological domain – cognitive and emotional impacts.

Sociocultural domain – societal expectations, cultural narratives, and family dynamics.

Health System domain – access to care, service delivery, and policy structures.

An initial open coding process was used to identify key concepts within transcripts. Codes were iteratively refined through team discussions, and axial coding was applied to connect codes within and across domains. The final themes were mapped using the framework, ensuring a structured and comprehensive understanding of menopausal experiences.

Table 1.

Coding table based on the Delanerolle and Phiri framework.

Table 1.

Coding table based on the Delanerolle and Phiri framework.

|

Domain

|

Initial Codes

|

Refined Themes

|

Illustrative Quote

|

| Biological |

Hot flushes, sleep disruption, joint pain, irregular bleeding |

Symptom burden and variability |

“I wake up drenched at night, and it feels like my body is not my own anymore.” (PID12) |

| Psychological |

Anxiety, depression, memory loss |

Cognitive-emotional distress |

“I feel like I am losing myself, my memory is gone, and nobody understands.” (PID7) |

| Sociocultural |

Stigma, family roles, workplace issues |

Cultural silence and social expectations |

“We don’t speak of these things in my family; it’s considered shameful.” (PID15) |

| Health System |

GP knowledge gaps, lack of HRT, fragmented care |

Structural barriers to care |

“I went to three clinics, and no one could explain what was happening to me.” (PID9) |

Ethics

Institutional ethical review board was obtained (Medical Research Ethics Committee, SQU MREC#3547) before the study commenced. All participants provided informed consent prior to the commencement of the study.

Results

The qualitative findings from 25 participants reveal a complex landscape of menopausal experiences shaped by biological changes, psychological challenges, sociocultural norms, and health system barriers. While individual narratives varied in intensity, collectively they portray menopause in Oman as a largely private, under-recognised life stage, occurring within a context of gendered expectations and fragmented care systems. The interplay of these four domains underscores both shared struggles and unique trajectories across Omani nationals and expatriate women.

Biological Domain: Diverse Symptom Burdens and Limited Management

Menopausal symptoms ranged from mild and manageable to severe and disruptive. Vasomotor symptoms of hot flushes and night sweats were among the most frequently reported, though their intensity varied. Several women, particularly PID1, PID7, and PID23, described debilitating night sweats that severely interrupted their sleep and daily functioning:

“I mainly have hot flushes and night sweats, which make it very uncomfortable at night.”

(PID1)

“The most difficult for me is the sleep, because I cannot sleep well at night, and this makes me feel more tired and depressed during the day.”

(PID23)

Others, such as PID12 and PID25, reported minimal symptoms, describing their transition as a natural and expected phase requiring little intervention:

“Honestly, I don’t have many complaints. I don’t feel the hot flushes or night sweats that other women talk about.”

(PID12)

Musculoskeletal pain including back pain, knee discomfort, and joint stiffness—was pervasive, often linked to housework and caregiving responsibilities. This physical strain frequently limited mobility and increased fatigue:

“Yes, it does affect me. It makes heavy work, cleaning, or carrying things harder. Walking long distances can also be difficult.”

(PID15)

Genitourinary concerns were reported but often normalised and left untreated, such as mild urinary leakage:

“Sometimes I leak a little urine when I cough, but with no pelvic pain.”

(PID8)

Participants overwhelmingly relied on self-care methods, such as rest, pacing, prayer, herbal remedies, or over-the-counter analgesics. Structured services like physiotherapy or pelvic health programmes were limited. This reinforced a cycle of silent endurance and acceptance of symptoms as inevitable.

Psychological Domain: Emotional Distress, Resilience, and Coping

Emotional wellbeing was closely tied to symptom severity and caregiving roles. Women with severe vasomotor or sleep disturbances reported high levels of fatigue, anxiety, and irritability. PID6 captured this overwhelming frustration:

“Yes, it’s too much for me. Makes me angry, I cannot control.”

(PID6)

Feelings of hopelessness were rare but present, especially when compounded by chronic sleep deprivation:

“Sometimes when I cannot sleep, I just feel like I cannot carry on.”

(PID7)

Conversely, women with milder symptoms demonstrated higher resilience, often framing menopause as a natural part of ageing. Prayer and spiritual practices were central coping mechanisms, providing comfort and emotional grounding.

“Prayer gives me peace and helps me feel calmer when my symptoms are strong.”

(PID1)

“Prayer, being with family, and doing housework or walking help me cope.”

(PID15)

Notably, formal psychological support such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) was completely absent from women’s narratives. Many participants had never heard of CBT or other evidence-based psychological interventions, relying solely on personal strategies and religious practices. PID8 highlighted this lack of awareness:

“I never used it. Maybe it can help, but I don’t know much about it.”

(PID8)

The few health care professionals that can deliver CBT further added to the systemic neglect due to limited-service provision. This left women vulnerable to prolonged emotional distress, particularly those managing both menopausal symptoms and demanding caregiving responsibilities.

Sociocultural Domain: Silence, Stigma, and Gendered Expectations

Menopause remains a largely private and stigmatised topic in Omani society. Women rarely discussed their experiences openly, even within families. Conversations were typically confined to sisters, daughters, or trusted female friends and were often brief and superficial:

“Sometimes, when I try to speak to my friends and neighbours who are around my age, the conversation always dies down immediately.”

(PID4)

“I feel shy to share these personal feelings openly.”

(PID21)

Many participants described feelings of embarrassment or shame surrounding menopause, reinforcing a culture of silence that discouraged help-seeking and perpetuated misinformation. PID6 encapsulated this isolation:

“No, nobody understands, and I feel like it is a private thing, and it is nobody’s business.”

(PID6)

Despite these barriers, informal female support networks particularly among sisters and daughters provided practical assistance with household tasks and emotional solidarity. However, these networks were not a substitute for systemic support, and many women continued to shoulder the bulk of domestic responsibilities regardless of physical discomfort or fatigue:

“My home is busy, noisy. Children and grandchildren make me so tired.”

(PID6)

The diaspora experience added complexity. Expatriate women, particularly those from South Asia and East Africa, often relied entirely on informal advice from peers rather than healthcare professionals. In addition, many approach alternative medicine such as herbal or Auyverdi clinics prior to starting HRT.

Health System Domain: Invisibility of Menopause in Care Pathways

Across all narratives, a consistent theme was the absence of proactive menopause care within the Omani health system. Consultations typically focused on chronic diseases such as hypertension or diabetes, and other midlife programmes such as osteoporosis and breast cancer screening, but no comprehensive menopause clinics with menopause ignored unless the woman herself raised the issue:

“Doctors only check my blood pressure and don’t ask me about my symptoms or mental wellbeing.”

(PID1)

“Unless you say something, they don’t ask about menopause.”

(PID12)

This neglect was compounded by structural barriers, including long wait times, crowded clinics, and limited treatment options. Several women expressed frustration at the lack of diversity in menopausal hormone treatment (HRT), delivery forms. PID15 reflected:

“I also understand that the only option for hormonal treatment is to take tablets. I wish there was other formats, like the patch.”

(PID15)

Participants voiced a strong desire for community-based education campaigns, exercise and relaxation programmes, and routine menopause screening at primary care level. These gaps were particularly stark for rural women, who faced greater travel distances and service inequities compared to urban populations.

Experiences with Menopause Hormone Treatment

Across the narratives, women’s experiences with Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) were characterised by limited access, low awareness, and lack of choice. Most participants had minimal knowledge of HRT, with many unfamiliar with its potential benefits or risks. Where awareness did exist, it was often shaped by informal discussions with friends or relatives rather than reliable medical guidance. Several women described frustration at the restricted range of HRT options available in government facilities, with oral tablets being the only format offered. PID15 reflected on this limitation:

“I also understand that the only option for hormonal treatment is to take tablets. I wish there was other formats, like the patch. I understand it is easier.”

(PID15)

A few women, particularly those with access to private healthcare or higher health literacy, reported some engagement with HRT but noted that information was sparse and counselling inadequate. PID25 emphasised the need for a more holistic and structured approach to menopause care:

“I would like to see a structured program for menopausal women that includes lifestyle advice, physical therapy, and mental health support alongside medication.”

(PID25)

For many, reluctance to consider HRT stemmed from fear of side effects, religious concerns, and a cultural preference for natural or spiritual remedies. One major fear was concern for breast cancer. Several women opted instead for herbal teas, massage, and prayer as primary management strategies. Others were never offered HRT by their healthcare providers, reflecting a passive health system model where menopause was only addressed when explicitly raised by the woman herself. These narratives highlight the urgent need for education, choice, and culturally sensitive counselling, ensuring that women can make informed decisions about HRT and access diverse treatment options tailored to their needs.

Differences Between Natural, Surgical, and Medical Menopause

The Omani narratives revealed distinct experiences and challenges depending on whether menopause occurred naturally, surgically, or through medical induction. The majority of participants reported natural menopause, where symptoms developed gradually and were often perceived as a normal part of ageing and life progression. These women tended to describe their transition with acceptance and patience, drawing on religious beliefs to frame menopause as a natural stage decreed by God. Symptoms such as hot flushes, joint pain, and sleep disturbance were often endured silently, with minimal medical intervention. PID12 reflected this outlook:

“Honestly, I don’t have many complaints. I don’t feel the hot flushes or night sweats that other women talk about.”

(PID12)

In contrast, women who experienced surgical menopause, such as those who underwent hysterectomy or oophorectomy, described a sudden and more intense onset of symptoms. This abrupt hormonal shift was associated with severe vasomotor symptoms, emotional instability, and profound fatigue, creating challenges in daily functioning. These women often felt unprepared for the immediate and overwhelming changes, as healthcare providers had not adequately explained the consequences of surgical menopause. PID15 highlighted the lack of counselling and support:

“I wish doctors would explain more about what happens after surgery. Everything came at once, and I was not ready.”

(PID15)

Participants who underwent medical menopause often due to treatments for chronic conditions or hormone-suppressing therapies described experiences similar to those of surgical menopause, with rapid symptom onset and limited information provided by clinicians. These women also faced heightened anxiety about their underlying health conditions, compounding the psychological burden of menopause. Across both surgical and medical menopause, there was a clear gap in preparatory education and follow-up care. Women reported being discharged after treatment or surgery without tailored advice on symptom management, lifestyle modifications, or available therapies such as HRT. This absence of structured support left many feeling isolated and uncertain about how to navigate their new health challenges. In contrast, women undergoing natural menopause tended to have a gradual adjustment period, relying on prayer, family support, and informal remedies to cope.

These findings highlight how the pace and context of menopausal onset profoundly shape women’s experiences in Oman. They underscore the urgent need for individualised counselling and care pathways, ensuring that women who experience surgical or medical menopause receive proactive education and follow-up support to mitigate the sudden physical and emotional disruptions they face.

Table 2 summarises the key themes from qualitative interviews with 25 women in Oman, using the

Delanerolle & Phiri Framework to explore menopausal experiences across

biological, psychological, sociocultural, and

health system domains. It links women’s direct experiences (

exposures) such as symptoms, caregiving roles, and healthcare interactions with the wider

determinants shaping them, including cultural norms, service gaps, and systemic barriers. Illustrative quotes provide insight into how menopause is understood and lived, highlighting both shared challenges and disparities between Omani nationals and expatriate women.

Table 2.

The consolidated themes, sub-themes, domain and corresponding illustrative quotes.

Table 2.

The consolidated themes, sub-themes, domain and corresponding illustrative quotes.

|

Theme

|

Sub-theme

|

Domain

|

Exposures

|

Determinants

|

Illustrative Quote

|

| Symptom burden and variability |

Vasomotor, musculoskeletal, genitourinary symptoms |

Biological |

Hormonal changes, natural ageing, physical strain from domestic labour |

Lack of menopause-specific health services, normalisation of symptoms |

“I have hot flushes at night, sweating, and I forget things easily.” (PID7) |

| Sleep disruption |

Poor sleep quality, night waking |

Biological |

Vasomotor symptoms, stress, musculoskeletal discomfort |

Absence of structured sleep support or interventions |

“Poor, 4 out of 10.” (PID7) |

| Emotional strain |

Anxiety, sadness, irritability |

Psychological |

Symptom severity, caregiving burden, lack of rest |

Limited psychological care, cultural stigma around mental health |

“Yes, too much for me. Make me angry, I cannot control.” (PID6) |

| Coping through spirituality |

Prayer, Quran recitation, quiet time |

Psychological |

Spiritual and cultural practices, reliance on faith |

Absence of formal counselling, culturally embedded coping norms |

“Prayer gives me peace and helps me feel calmer.” (PID1) |

| Cultural silence and stigma |

Shyness, taboo, secrecy |

Sociocultural |

Lack of open dialogue, generational silence, fear of judgement |

Societal norms of modesty, taboo around discussing women’s health |

“I feel shy to share these personal feelings openly.” (PID21) |

| Informal female support |

Sisters, daughters, female friends |

Sociocultural |

Reliance on close female relatives for advice and practical help |

Absence of formal support systems, strong intergenerational ties |

“When my daughters help me at home.” (PID8) |

| Gendered household expectations |

Continued caregiving despite symptoms |

Sociocultural |

Domestic workload, caregiving for children and elderly family members |

Gendered division of labour, lack of recognition of women’s needs |

“My home is busy, noisy. Children and grandchildren make me so tired.” (PID6) |

| Neglect in healthcare |

Lack of proactive menopause questioning |

Health System |

Consultations focused on chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension |

Biomedical model prioritising disease management over holistic care |

“Unless you say something, they don’t ask about menopause.” (PID12) |

| Limited treatment access |

Restricted HRT forms, poor education |

Health System |

Limited HRT availability (mainly oral tablets), absence of non-pharmaceutical care |

Centralised service design, lack of clinician training and education |

“I wish there was other formats, like the patch.” (PID15) |

| Rural vs urban inequities |

Access challenges for rural women |

Health System |

Distance to clinics, lack of transport, fewer local services |

Geographic disparities, resource concentration in urban areas |

“Women in rural areas may find it harder.” (PID17) |

Table 3.

Colloquial terms.

Table 3.

Colloquial terms.

|

Arabic Term

|

English Translation

|

Menopause Context

|

|

Harara dakhiliya (حرارة داخلية) |

Internal heat |

Describes hot flushes and night sweats |

|

Nisyan kathir (نسيان كثير) |

Frequent forgetting |

Cognitive difficulties and memory lapses |

|

Ta’ab shadid (تعب شديد) |

Extreme tiredness |

Fatigue and lethargy |

|

Taghyeer raheeb Fi AlUmr ((تغيير رهيب في العمر

|

Drastic change in life |

Perimenopausal transition |

|

Kalam mamnoua (كلام ممنوع) |

Forbidden words |

Taboo around discussing menopause |

|

Al-waja’ al-daa’im (الوجع الدائم) |

Persistent pain |

Chronic musculoskeletal discomfort |

|

Haalat qaliq (حالات قلق) |

Anxiety episodes |

Psychological distress |

Colloquial Context Narrative

Colloquial expressions played a central role in how Omani women articulated their menopausal experiences. The phrase harara dakhiliya (“internal heat”) was frequently used to describe vasomotor symptoms, particularly hot flushes and night sweats. This term reflects both the physical sensation and the cultural framing of menopause as an internal, private issue. Similarly, nisyan kathir (“frequent forgetting”) conveyed cognitive changes such as memory lapses, which were often stigmatised and rarely discussed outside trusted circles.

The use of kalam mamnoua (“forbidden words”) illustrates the deep-rooted cultural silence surrounding menopause. Many women avoided the biomedical term altogether, using euphemisms to maintain propriety within families and communities:

“We call it internal heat, not menopause, because saying the word is not proper in front of family.”

(PID5)

Expressions like al-waja’ al-daa’im (“persistent pain”) were linked to musculoskeletal and joint discomfort, underscoring the normalisation of physical suffering as part of women’s caregiving roles. Meanwhile, haalat qaliq (“anxiety episodes”) captured the emotional burden, often hidden behind a facade of strength.

These colloquial terms highlight how language shapes understanding and care-seeking behaviours. They reflect a broader sociocultural context in which menopause is simultaneously embodied, spiritualised, and silenced leaving many women without the words, resources, or safe spaces to fully express their needs.

Cultural and Religious Beliefs Shaping Menopausal Experiences in Oman

The findings revealed that Omani culture and Islamic religious beliefs deeply shape how menopause is perceived, discussed, and managed. Menopause was often framed as a natural, God-given stage of life, accepted with patience and humility rather than approached as a medical condition. Many participants described their symptoms through a lens of spiritual meaning, viewing them as part of a divine plan. This spiritual perspective fostered resilience and coping, with prayer, Quran recitation, and reflection serving as key strategies for emotional regulation and stress relief.

“Prayer gives me peace and helps me feel calmer when my symptoms are strong.”

(PID1)

“Prayer and reading Quran calm me. When I am exhausted, anxious, or tired, Quran makes me feel at peace.”

(PID10)

Cultural expectations around modesty and privacy reinforced silence about menopause, particularly in mixed-gender or intergenerational settings. Women described avoiding explicit discussion of menopausal symptoms, even within their families, to maintain propriety and prevent embarrassment. This cultural restraint was especially evident when discussing topics such as vaginal dryness, libido changes, or urinary incontinence, which were considered “kalam mamnoua”(forbidden words).

“We call it internal heat, not menopause, because saying the word is not proper in front of family.”

(PID5)

Religious and cultural norms also reinforced women’s caregiving roles, with menopausal women expected to continue fulfilling household responsibilities despite physical and emotional challenges. While faith and cultural identity provided a sense of meaning, they also contributed to under-reporting of symptoms and reluctance to seek professional care. This intersection of belief, silence, and service gaps highlights the need for culturally sensitive approaches that respect religious values while encouraging open dialogue and appropriate health interventions.

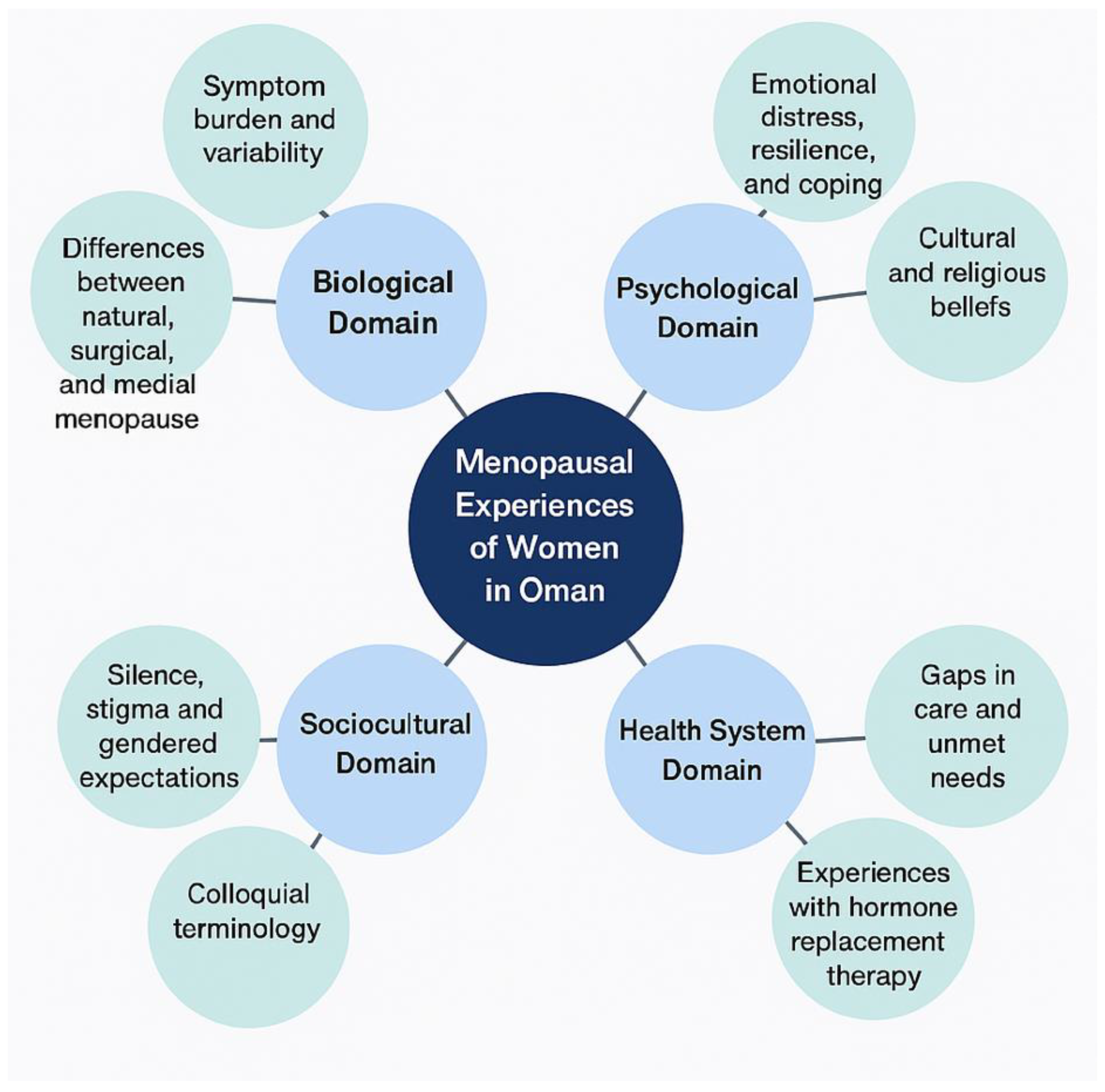

Figure 2.

Bubble-map of the themes and contextual components identified.

Figure 2.

Bubble-map of the themes and contextual components identified.

Discussion

Main findings: This qualitative study provides a detailed exploration of menopausal experiences among Omani and expatriate women living in Oman, revealing how biological, psychological, sociocultural, and health system factors interact to shape this life transition. The findings highlight that menopause is primarily understood as a natural process, framed within religious and cultural contexts that emphasise acceptance and silence rather than medical engagement. While vasomotor, musculoskeletal, genitourinary, and sleep-related symptoms were common, their expression and severity varied widely. Women experiencing natural menopause described a gradual transition, whereas those with surgical or medically induced menopause reported abrupt, intense symptoms accompanied by feelings of unpreparedness and emotional strain. Across all groups, coping strategies relied heavily on self-management, family support, and prayer rather than structured clinical interventions.

A study by Faiza Al Zidjali et al in 2023 looked at impact of post-menopausal osteoporosis on the lives of Omani women and the use of cultural and religious practices to relieve pain, interviewed 25 women also found that Muslim prayers, recitation of Quranic verses, and herbal remedies were among coping strategies for pain in this population [

19]. The study also exposes significant gaps in healthcare provision. Menopause was rarely addressed proactively by healthcare professionals, with consultations focused on chronic conditions such as diabetes or hypertension. Access to menopausal hormone treatment (MHT) was limited, with oral tablets often the only available option in public and private health facilities. Cultural stigma further restricted open discussion, with sensitive symptoms such as sexual health or urinary incontinence described using euphemisms like

harara dakhiliya (“internal heat”) or entirely left unspoken. This silence was especially marked among the older women or less educated. The breast cancer screening programme is available for both Omani and Expatriate patients especially via the mobile mammogram unit [

20]. These findings underscore the need to now focus on mature women’s health. These patient interviews highlight how both limited and, in some areas, fragmented health services for menopausal care in addition to cultural norms reinforce each other, leaving many women to navigate menopause in isolation

Population Science

From a population health perspective, these findings have critical implications for Oman’s rapidly ageing society. With life expectancy rising, a growing proportion of women will spend decades in perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause, making midlife health a pressing public health concern. The narratives highlight the dual burden of symptoms and caregiving, where women continue to manage households and provide care for children and elderly relatives despite fatigue, pain, and sleep disruption. This unrecognised labour contributes to hidden health inequalities, with menopausal women bearing a disproportionate physical and emotional load that impacts family and community wellbeing.

The study also identifies intersectional challenges faced by expatriate women, that are part of the Omani workforce, particularly in service sectors. These women are often excluded from health planning, lack culturally and linguistically appropriate services, and face barriers to seeking care due to and lack of insurance. In general women over 55 are not employed in nonprofessional careers. Their experiences reveal structural gaps that, if unaddressed, could perpetuate inequities and widen health disparities. Women who do not have insurance, have to pay out of pocket for expensive investigations and treatment, thus more affordable menopausal clinics in private sector are recommended.

Population-level strategies must therefore move beyond individualised care to address collective determinants of health, including gender norms, socioeconomic conditions, and rural–urban inequities. Awareness campaigns, community-based education, and inclusive health services are essential to ensuring that menopausal health is recognised as a societal priority rather than a private struggle. Importantly, these initiatives must engage men and younger generations to normalise discussion and support, breaking the cycle of silence and stigma that emerged so strongly in this study.

Clinical Implications

The clinical narratives reveal a striking absence of structured menopause care pathways covering the whole of Oman. Primary care providers rarely initiated conversations about menopause, leaving women to self-manage or seek help only when symptoms became severe. This reactive model results in missed opportunities for early intervention and holistic management. Training healthcare professionals to routinely screen for other menopausal symptoms, including psychological, mental and sexual health at the same time as screening for osteoporosis and breast cancer, could significantly improve quality of care and reduce long-term complications such as depression.

Expanding the range and accessibility of treatment options, particularly HRT, is critical. Offering patches, gels, and other formulations would provide women with choices tailored to their preferences and medical needs, especially those unable to tolerate oral medications. In addition, integrating lifestyle interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, physiotherapy, relaxation classes, and group education sessions could empower women to manage their symptoms more effectively.

Culturally sensitive counselling is essential to address misconceptions and religious concerns around menopause treatments. Involving female healthcare providers and creating safe, private spaces for consultation would encourage women to seek care without fear of judgement. Furthermore, multidisciplinary clinics bringing together gynaecology, endocrinology, breast clinics, mental health, and physiotherapy services would align with best practices for comprehensive midlife women’s health care. More awareness needs to be carried out to clarify the benefits and side effects of HRT especially addressing women’s fear associated with HRT and breast cancer.

Policy Recommendations

The findings call for policy-level action to integrate comprehensive menopausal health into Oman’s national health agenda. Menopause should be recognised as a public health priority, similar to maternal and child health, with dedicated resources and measurable indicators. Policy frameworks must address both clinical care delivery and community engagement, ensuring services are accessible, equitable, and culturally appropriate.

Health policies should include mandatory training on menopause for all primary care and secondary providers with updated National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment need to be better implemented. Expanding the essential medicines list to include a full range of HRT formulations is vital to improve treatment accessibility. Moreover, policies should target rural–urban disparities through mobile clinics and outreach programmes, ensuring women in remote areas are not left behind.

Community education campaigns are also needed to reduce stigma and promote health literacy. These campaigns should be co-designed with women, religious leaders, and community groups to ensure cultural alignment and acceptance. Finally, expatriate women must be included in health planning, with policies that include midlife health services irrespective of employment status or nationality such as the free breast cancer screening mobile unit. More of such initiatives are needed.

Table 4.

Policy Recommendations for Menopausal Health in Oman.

Table 4.

Policy Recommendations for Menopausal Health in Oman.

|

Priority Area

|

Policy Action

|

Intended Impact

|

| Healthcare Workforce Training |

Mandatory menopause education for primary care providers and nurses |

Improve clinician knowledge and proactive care |

| Routine Screening and Diagnosis |

Integration of menopause screening into annual health checks |

Early identification and management of symptoms |

| Access to HRT |

Expand essential medicines list to include patches, gels, and other HRT formulations |

Increase treatment choice and adherence |

| Community Education |

Public health campaigns using culturally sensitive language and local leaders |

Reduce stigma and promote health literacy |

| Rural–Urban Equity |

Mobile clinics and outreach services for rural areas |

Reduce geographical disparities in access |

| Multidisciplinary Care |

Establish menopause clinics with gynaecology, mental health, physiotherapy, and lifestyle services |

Holistic, patient-centred care |

| Expatriate Health Inclusion |

Policies ensuring basic menopausal care for all women, regardless of employment or residency status |

Address systemic inequities |

By situating menopause within a broader framework of gender, culture, and health system reform, Oman can develop a comprehensive strategy that supports women through this critical life stage. Such action would not only improve individual health outcomes but also strengthen families, workplaces, and communities, contributing to national wellbeing and resilience.

Strengths: This study is among the first to explore menopausal experiences in Oman, incorporating both Omani and expatriate women across different menopausal stages. Using the Delanerolle & Phiri Framework allowed a comprehensive view of biological, psychological, sociocultural, and health system influences. Inclusion of diverse participants from urban and rural settings, and the use of verbatim quotes, enhanced the depth and authenticity of the findings.

Limitations: As a qualitative study, the results are not generalisable to all women. The small sample size, limited to outpatient attendees, may exclude those with restricted healthcare access. Some participants may have withheld sensitive details due to social desirability or cultural norms. Expatriate perspectives mainly represented South and Southeast Asian groups, with limited representation from other backgrounds. Future research using mixed methods and broader sampling is recommended to validate and expand these findings.

Conclusion

This study provides a nuanced understanding of menopausal experiences among Omani and expatriate women, highlighting the intersection of biological, psychological, sociocultural, and health system factors. Menopause was predominantly framed as a natural, spiritual transition, yet marked by silence, stigma, and limited clinical engagement. Women reported diverse symptom burdens, with those experiencing surgical or medical menopause facing more abrupt and challenging transitions, often without adequate support. The findings underscore the urgent need for culturally sensitive, accessible, and equitable menopause care pathways, including expanded HRT options and routine screening. Addressing these gaps through education, policy reform, and community engagement, and comprehensive health programmes will be essential to improving midlife health in Oman.

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. LAK and NAR submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study. GHU and team collected data. GD and NAR conducted the data analysis. GD, LAK and NAR wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Medical Research Ethics Committee, SQU MREC#3547

Consent to participate

Obtained

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

Code availability

Not applicable

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Paula Briggs, Donatella Fontana, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumde, Heitor Cavalini, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Chukwuemeka Chidindu Njoku, Ayyuba RABIU, Chijioke Chimbo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuaz, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Susan Nweje, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Michael Nnaa Otis, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Kim-Yen Lee, Siti Nurul Aiman Ali Madinah, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Xiu-Sing Wong, John Yen-Sing Lee, Yee-Theng Lau, Alyani Mohamad Mohsin, Nor Fareshah Mohd Nasir, Diana Suk-Chin Lau, Farhawa Zamri, Artini Abidin, Aini Hanan Azmi, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Fatin Imtithal Adnan, Puong Rui-Lau, Xin-Sheng Wong, Geok-Seim Lim, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Karen Kristelle, Asma’ Mohd Haslan, Noorhazliza Abdul Patah, Vaitheswariy Rao Nalathambi, Juhaida Jaafar, Jinn-Yinn Phang, Lee Leong Wong, Nurfauzani Ibrahim, Siew-Yew Ting, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Norhazura Hamdan, Min-Huang Ngu, Choon-Moy Ho, Safilah Dahian, Daniel Leong-Hoe Ngu, Sing-Yee Khoo, Kamilah Dahian, Jeffrey Soon-Yit Lee, Shubashini Kanagaratnam, Amirah Fazira Zulkifli, Manisha Mathur, Rukshini Puvanendran, Farah Safdar, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Raksha Aiyappan, Ganesh Dangal, Puja Lam, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Prasanna Herath, Damayanthi Dassnayake, Chandrani Herath, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Cristina Laguna Benetti-Pinto, Renan Massao Nakamura, Daniela Angerame Yela, Gabriela Pravatta Rezende, Renan Massao Nakamura, Isaac Lartey Narh, Kwasi Eba-Polley, Catherine Narh Menka, Prince Osei, Nana Osei, Lemuel Lartey, Bernard Bortieh, Cletus Kumi, Elijah Boafo, Janet Ayorkor Anyetei, Edel Issabella Arthur, Horatio King Glover, Fredrick Amoah, Ethel Larteley Boye, Zerish Lamptey, Laurinda Gyan, Bharat Prasad, Shaziya Noor, Kumari Shilpa, Poonam Singh, Usha Jha, Manu Chatterjee, Oscar Mahinyila, Alosisia Shemdoe, Kornelio Mpangala, Filbert Ilaza , Zepherine Pembe, Mpoki Kaminyoge, Thomas Alon

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Delanerolle, G. et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 13, e196-e198 (2025).

- Troìa, L., Martone, S., Morgante, G. & Luisi, S. Management of perimenopause disorders: hormonal treatment. Gynecological Endocrinology 37, 195-200 (2021).

- Ambikairajah, A., Walsh, E. & Cherbuin, N. A review of menopause nomenclature. Reproductive health 19, 29 (2022).

- Santoro, N., Roeca, C., Peters, B. A. & Neal-Perry, G. The menopause transition: signs, symptoms, and management options. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 106, 1-15 (2021).

- Davis, S. R. & Baber, R. J. Treating menopause—MHT and beyond. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 18, 490-502 (2022).

- Kingsberg, S. A., Larkin, L. C. & Liu, J. H. Clinical effects of early or surgical menopause. Obstetrics & Gynecology 135, 853-868 (2020).

- Mishra, G. D., Chung, H.-F., Hickey, M., Kuh, D. & Hardy, R. Menopause and Hysterectomy. A Life Course Approach to Women's Health, 49 (2023).

- Osman, Y. M., El-Kest, H. R. A., Awad Alanazi, M. & Shaban, M. I’m still quite young: women’s lived experience of precocious or premature menopause: a qualitative study among Egyptian women. BMC nursing 24, 612 (2025).

- Al-Zoqari, H. S. Factors Shaping Menopause Management Practices among Arab Women: A Systematic Review. (2025).

- Al-Mawali, A. et al. Prevalence of risk factors of non-communicable diseases in the Sultanate of Oman: STEPS survey 2017. PLoS one 16, e0259239 (2021).

- EAST, G. M. & JASSIM, G. WOMEN'S HEALTH IN. Healthcare in the Arabian Gulf and Greater Middle East: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals-E-Book, 64 (2023).

- 12 Rinker, C. H. in Routledge Handbook on Women in the Middle East 535-547 (Routledge, 2022).

- Kemp, L. J. & Madsen, S. R. Oman's labour force: an analysis of gender in management. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 33, 789-805 (2014).

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women's Health Research. (2025).

- Al-Saadoon, M., Al-Adawi, M. & Al-Adawi, S. Socio-cultural constraints in protecting child rights in a society in transition: A review and synthesis from Oman. Child indicators research 14, 239-267 (2021).

- Ryan, J., Al Sheedi, Y. M., White, G. & Watkins, D. Respecting the culture: Undertaking focus groups in Oman. Qualitative Research 15, 373-388 (2015).

- Al Kindi, B. H. Development of a culturally sensitive evaluation framework for the Oman Research Council's Road Safety Research Program, Queensland University of Technology, (2020).

- Delanerolle, G. et al. An Exploration of the Mental Health impact among Menopausal Women: The MARIE Project Protocol (International Arm). medRxiv, 2023.2011. 2026.23299012 (2023).

- Zadjali, F. A., Brooks, J., O'Neill, T. W. & Stanmore, E. Impact of postmenopausal osteoporosis on the lives of Omani women and the use of cultural and religious practises to relieve pain: A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Health Expectations 26, 2278-2292 (2023).

- Al Lawati, N. A. & Al Harthi, H. Impact of Screening Programs on Stage Migration in Breast Cancer.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).