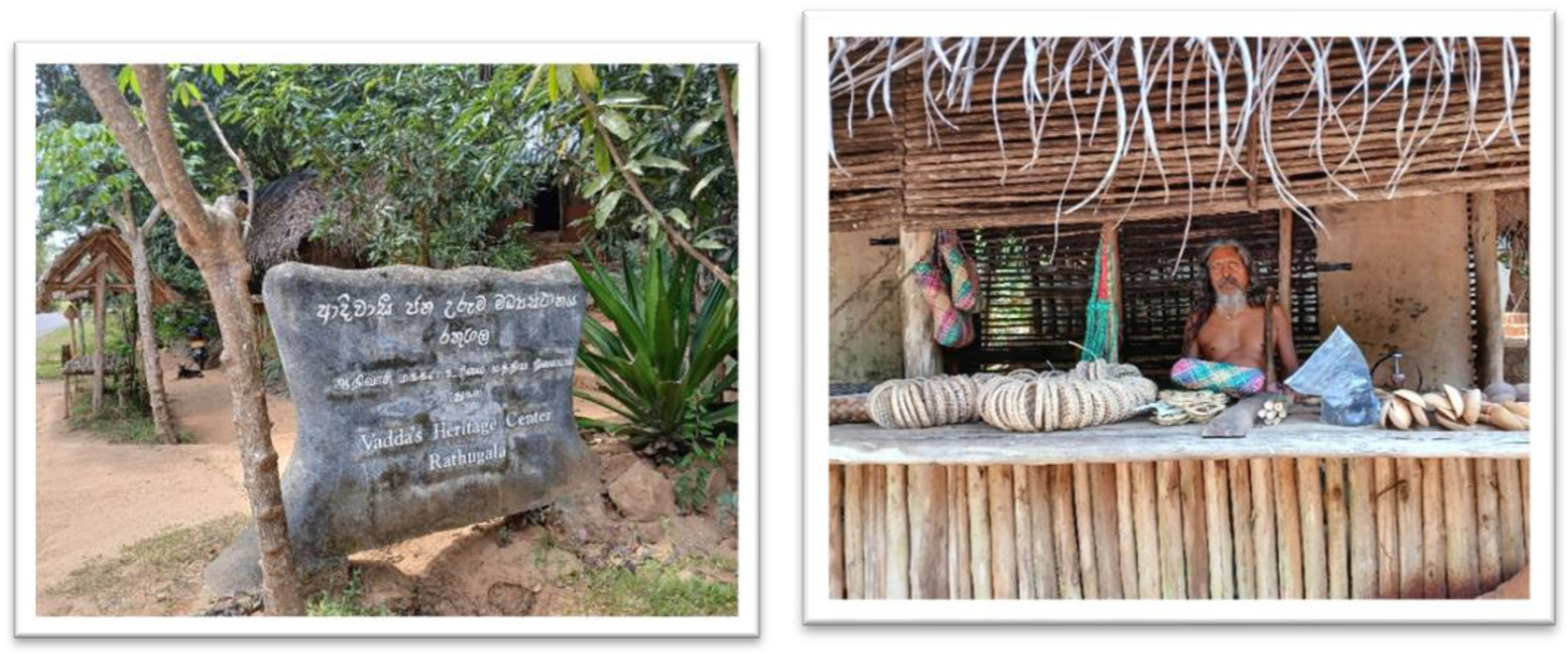

Vedda’s Heritage Center, Rathugala, 2025 Photo – author.

1. Introduction

Menopause whether natural (the permanent cessation of menstruation for at least 12 consecutive months without other causes), surgical, or medically induced marks the end of menstruation.[

1] This transition is shaped by biological, psychological, social, and cultural influences.[

2] While hormonal changes and menstrual cessation are universal, individual experiences vary based on geography, ethnicity, and socio-economic factors. Understanding menopause is especially relevant for Sri Lanka’s indigenous Vedda people, the island’s earliest inhabitants.[

3]

Sri Lanka’s indigenous Vedda people, recognised as the island’s earliest inhabitants, face historical marginalisation and socio-political challenges. Archaeological evidence traces human habitation back 35,000 years, with the earliest remains linked to the Balangoda.[

4] These prehistoric hunter-gatherers are believed to be the ancestors of the present-day Vedda community, which has maintained a continuous presence while adapting to environmental and socio-political shifts over millennia. Their cultural and biological uniqueness has been well documented,[

3] and unlike the Sinhalese and Tamil populations, they have largely preserved their isolation with deep genetic ties to India.[

5]

Sri Lankan indigenous women, particularly from the Vedda community, have historically preserved their cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. Their contributions to indigenous practices, such as herbal medicine, food preparation, and rituals, are deeply tied to community identity.[

6] Their experience of menopause reflects unique cultural perspectives shaped by their traditional way of life, yet they face challenges including cultural erosion, socio-economic disparities, and limited access to healthcare services.[

7]

Over the past century, Sri Lanka’s Vedda population has significantly declined to 5000-10000, attributing to factors such as assimilation, displacement and loss of traditional lands.[

8] At present, indigenous communities primarily reside in Monaragala, Ampara, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura and Badulla which is based within the Eastern, Uva and North Central provinces.[

6]

Within the community, approximately 50% are women, thus there is a scientific and ethical imperative to explore the menopausal experiences. Understanding the perspectives, beliefs and health needs of indigenous women are vital to better support their needs, to achieve this, we conducted a qualitative study with aim to fulfil our understanding and address a vital research gap and help amplify the voices of a marginalised community so that local healthcare providers consider their needs better whilst empowering the women to make informed choices about the health.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This qualitative study, part of Work Package 2a (WP2a) within the MARIE Project, explores culturally embedded perceptions and lived experiences of menopause among Sri Lanka’s indigenous population. The MARIE Project, a global women’s health initiative, examines the physical and mental impacts of menopause across diverse populations. As a key study site, Sri Lanka provides valuable insights into how cultural, biological, and socio-economic factors shape menopausal experiences.

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in “Rathugala”, a Vedda settlement in Monaragala District, Sri Lanka, home to one of the country’s few remaining indigenous communities. This study adopts an indigenous and decolonial approach, emphasising relational and culturally embedded knowledge rather than standardised sampling methods. Indigenous methodologies prioritise depth of engagement and co-created understanding, fostering meaningful dialogue and mutual respect and shared meaning-making.[

9] In line with these principles, a sample of five indigenous menopausal women was selected.

By incorporating relational knowledge production, the study promotes a culturally responsive understanding of menopause within the Vedda community, allowing perspectives to emerge naturally through storytelling and community involvement.

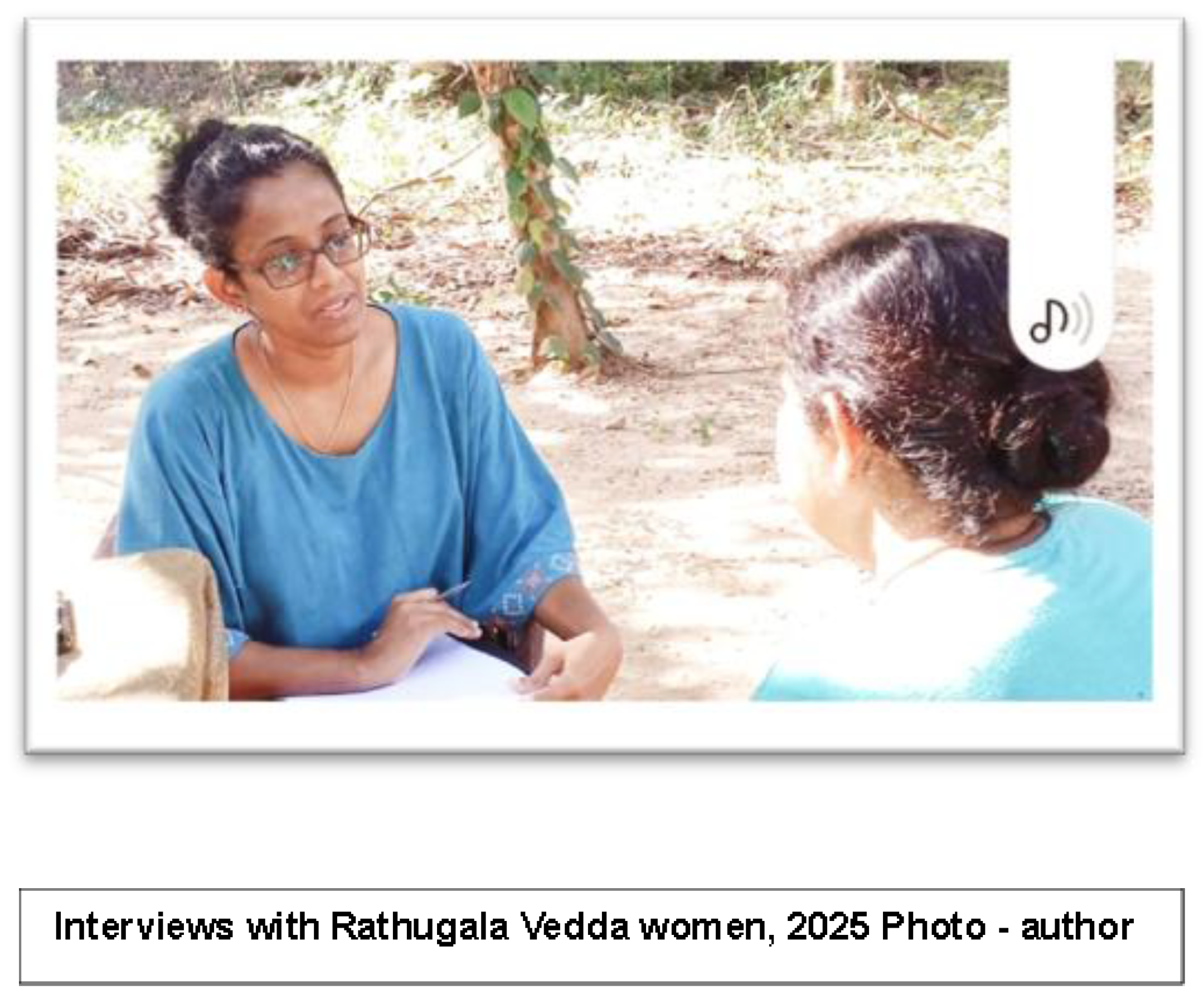

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, focusing on menopausal women of varying ages. Recruitment was facilitated by a trusted grassroots community health worker in “Rathugala”, who possessed deep cultural knowledge and strong community ties.

2.3. Data Collection Tool and Procedure

Data were gathered through comprehensive, semi-structured interviews utilising a study-specific interview guide. The interview guides were developed to explore lived and perceived experiences across the following areas:

Perception and personal attitudes or beliefs about menopause

Experienced menopausal symptoms and impact

Coping mechanisms and managing menopausal symptoms

Influence of cultural beliefs and traditional practices

Sources of information, educational needs and healthcare support

Accessibility and barriers to care

Interviews were conducted in Sinhala, with culturally sensitive interpretation for spiritual or ritualistic concepts when needed. They took place in participants’ homes or community centers, ensuring a comfortable and private environment. Each session lasted 45–60 minutes and was audio-recorded with prior informed consent. Data were collected from five recruited indigenous women to capture their nuanced lived experiences of menopause.

2.4. Data Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, translated into English, and analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework.[

10] Both deductive (interview guide-based) and inductive (participant-driven) coding were applied, with manual coding ensuring organised analysis. A culturally tailored semi-structured interview guide, developed through expert consultations and pilot testing, aligned with study objectives.

A single moderator conducted interviews for consistency, while interviewers received training in qualitative techniques. Interviews were held in preferred settings, ensuring privacy and comfort. Sessions were audio-recorded, supplemented with field notes, and transcribed with accuracy checks by bilingual researchers to preserve cultural authenticity. Interviewers maintained reflective journals, and collaboration with a local Public Health Midwife ensured cultural appropriateness. Transcripts were cross-checked, with ambiguities clarified through follow-ups to enhance reliability.

2.5. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Ruhuna (Ref. No: 2025.02.532). Before visiting the area, necessary approvals were obtained from community health authorities. Women were informed at an early stage with the support of primary healthcare officers, and written informed consent was obtained.

To accommodate illiterate participants, appropriate measures were implemented to ensure their voluntary participation and right to withdraw. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained, with pseudonyms used in all records.

3. Results

Five indigenous women (aged 49–64) from “Rathugala”, a Vedda settlement in Monaragala District, Uva Province, Sri Lanka, participated in this study. With minimal formal education, they primarily relied on subsistence farming, household labor, and informal work. All were married to Indigenous men, had three to six children, and lived with basic facilities. Their interaction with outside society was limited, with information shared solely through verbal communication.

Thematic analysis revealed six interrelated themes (Table 1) highlighting overlooked aspects of menopause in low-resource settings. These themes encompass biological, psychological, social, and cultural influences on women’s experiences. Findings expose challenges in symptom management, healthcare access, societal perceptions, and traditional beliefs. Additionally, they underscore how resource limitations, inadequate medical support, and social stigma shape menopausal experiences, stressing the need for culturally sensitive interventions and awareness programs.

Evidence before this study

There is limited research on the Sri Lankan menopausal experience, particularly among indigenous populations. There is a significant gap in understanding how indigenous communities in Sri Lanka experience and perceive menopause.

Added value of this study

This is the first study from the indigenous populations in Sri Lanka that explores their menopausal experiences thus, addressing a significant gap in existing research. This work provides initial evidence on how menopause is perceived and managed within these communities, offering valuable insights for culturally sensitive healthcare interventions.

Implications of all the available evidence

Initial evidence of this study provides critical insights that can inform clinical practice, public health strategies, and global health policies for women from indigenous communities. Clinically, it highlights the need for culturally sensitive care approaches that acknowledge and address the unique experiences of Indigenous women, moving beyond the perception of menopause as merely a natural aging process. On a broader scale, the data enriches the scientific community's understanding of menopause in underrepresented populations and underscores the importance of inclusive research in shaping equitable health interventions worldwide |

3.1. Loss of Fertility and Life Transition

Women in this community typically begin childbearing in early adolescence, seeing it as a key life milestone. They inherit ancestral knowledge about fertility’s natural decline but have uncertain perceptions about menopause’s effects on health. While aware of its inevitability, they express little concern or deep understanding of the maturation process (

Table 2).

Their experience of menopause differs, shaped by knowledge passed down from recent family members. However, they accept it as a natural transition and do not seek advice from formal or informal health professionals.

3.2. Limited Access to Menopausal Health Information and Services

Participants lacked access to structured menopause information, worsened by illiteracy and the absence of formal education. They showed little interest in learning about it, viewing menopause as separate from their lives. Their isolation due to tribal characteristics, limited social interactions, transportation barriers, digital exclusion, and illiteracy further restricted awareness of treatment options and symptom management.

This gap highlights a significant shortfall in the healthcare system (

Table 3), compounded by their limited access to knowledgeable resource personnel for support.

The lack of menopause knowledge and knowledge seeking behavior led to confusion, symptom misinterpretation, and missed early interventions. This health literacy gap left indigenous women unprepared, causing unnecessary suffering from untreated symptoms. Over time, it affected their quality of life and strained family relationships, as emotional and physical challenges remained unaddressed.

3.3. Menopausal Experiences and Their Impact on Health, Family, and Overall Quality of Life

Participants described menopause as a sudden, transformative experience with intense physical and emotional symptoms. Struggling with precise vocabulary, they expressed their experiences through vivid metaphors (

Table 4) and emotive language.

Menopause’s impact extends beyond physical discomfort, causing psychological distress, social isolation, and a deep sense of personal loss. Many women, constrained by introversion and limited awareness, suffer in silence. For some, it signals physical decline or loss of identity. This unspoken struggle disrupts family dynamics, strains emotional connections, and worsens household relationships. Over time, these challenges erode quality of life, leaving women feeling isolated, marginalized, and unsupported.

3.4. Coping Mechanisms and Treatment Practices During Menopause

With no formal treatment options and limited awareness, women relied on culturally embedded coping mechanisms (

Table 5). Rooted in tribal heritage, these practices included herbal and traditional remedies passed down through generations, serving as both a reflection of cultural continuity and their only accessible relief from menopausal symptoms.

Adaptation and self-reliance were another method of coping the mechanism by the women (

Table 6).

Despite the challenges, some women managed to find a positive perspective on their menopausal journey (

Table 7).

While the majority of women were either unaware of or rarely sought help from available community health care personnel, some did turn to them when faced with severe and persistent symptoms that offered no relief through other means (

Table 8). However, adherence to prescribed treatments remained notably poor, reflecting gaps in trust, understanding, and sustained engagement with healthcare options.

These adaptive strategies highlight women’s resilience in navigating health challenges within limited systems. However, relying solely on herbal remedies without clinical evaluation may delay appropriate care and worsen underlying health issues.

3.5. Psychosocial Impact and Gendered Dimensions of Menopause

Menopause proved to be a deeply complex experience, sparking emotional reflections and gendered perceptions of suffering. Several participants internalised negative associations with being female, linking physical decline to a perceived loss of value, identity, and purpose (

Table 9). The interplay of emotional, social, and cultural factors underscored psychological distress, social isolation, and shifts in familial roles during this transition.

These narratives underscore the deep social and psychological challenges of menopause, rooted in traditional gender roles and expectations. Isolation and the lack of community dialogue further intensify this burden, leaving many aging women without the support or recognition they need during this critical life stage.

3.6. Accessibility and Barriers to Healthcare

Geographic and systemic barriers made healthcare access difficult, with participants citing long travel distances, unreliable transport, and financial constraints. The lack of specialized menopausal care and dismissive attitudes from providers further marginalized women within the healthcare system (

Table 10).

These barriers not only delayed help-seeking but also discouraged women from expressing their symptoms. Although rural hospitals were present, they were often seen as inadequate for addressing the specific needs of aging women, reinforcing their sense of neglect and marginalization.

3.7. Emerging Trends and Community-Level Gaps

Community health workers, particularly Public Health Midwives (PHMs), were the most accessible providers but primarily focused on maternal and child health, leaving aging women underserved (

Table 11). While community health nurses could help bridge this gap, their limited numbers and existing responsibilities further restrict their capacity to provide specialized menopausal care.

These insights highlight the urgent need for health policy reforms and targeted community advocacy to address the unique challenges faced by indigenous postmenopausal women in rural areas. Prioritising their needs is essential for ensuring equitable healthcare access and improving overall well-being.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the complex, overlooked experiences of Sri Lankan Indigenous women navigating menopause, shaped by marginalisation, cultural traditions, and rural health inequities. A critical finding is the absence of culturally tailored, accessible health information, fostering fear and confusion.[

11] Misinterpretation of symptoms and insufficient healthcare interventions further widen this gap.[

12,

13]

Menopause is often perceived as a decline in identity, reinforcing systemic neglect and social isolation.[

14] Vedda women, in particular, face barriers such as illiteracy, geographic isolation, and exclusion from health initiatives.[

15] Limited awareness leaves them unprepared for risks like osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.[

16] However, cultural coping strategies, including herbal remedies and ancestral practices, offer resilience.[

17]

Access to care remains restricted due to financial strain, discrimination, and a lack of culturally sensitive interventions. Indigenous women rarely receive medical information on menopause or access to treatments such as HRT.[

18]

Despite these challenges, they advocate for community-based education, improved healthcare accessibility, and culturally inclusive health systems. Their voices call for urgent reforms to address disparities and promote equitable menopausal care.

4.1. Implication

Sri Lanka’s healthcare policies must address critical gaps in reproductive and geriatric care for Indigenous women. Decolonising health education through holistic approaches and cultural competency training for PHMs and rural staff is essential. Community-based models, developed with Indigenous leaders, should ensure linguistically and culturally appropriate care. Recognising menopause as a complex transition shaped by land, ancestry, and community is vital for equitable healthcare.

4.2. Recommendations

Sri Lanka’s public health system must adopt a culturally inclusive approach to supporting Indigenous women’s health. Menopause education, along with basic literacy and school education, should be prioritised to empower women and improve health awareness. Training PHMs and healthcare workers in cultural competency will enhance engagement. Traditional herbal remedies should be documented and integrated safely. Mobile clinics and decentralised services can improve access, while Indigenous women’s leadership in healthcare planning ensures representation. These steps will promote equitable, holistic care and address systemic neglect.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights menopause as a deeply personal yet overlooked experience for Sri Lankan Indigenous women. Marked by resilience and cultural strength, they navigate this transition with ancestral knowledge and community support. Their voices offer a roadmap for inclusive healthcare, calling for recognition, equity, and systemic change. Addressing their needs is essential for healing historical neglect and fostering holistic well-being.

MARIE Collaboration

MARIE Consortium: Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Suk-ChinLaw, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Donatella Fontana, Carol Atkinson, Nana Afful-Mintah Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Kaushini Peiris, Abirame Shiwakumar, Mohommad Haddadi, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Hospital Pantai Cheras, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, , Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lamiya Al-Hkarusi, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Nicholas Panay, Nihal Al-Riyani, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Ramya Palanisamy, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Kathryn Elliot, Ramiya Palanisamy, Yassine Bouchareb, Gowri Vaidyanathan, Bernard Mbwele, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Irfan Muhammad, Rabia Kareem, Ashish Shetty, Ganesh Dangal, Suman Pant, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Kingshuk Majumder, Victoria Corkhill, Andy Fairclough.

Availability of Data and Material

The data shared within this manuscript is available within government organisations and their ministries or departments of health and in public reports.

Code Availability

Not applicable

Author Contributions

GD conceptualised the MARIE project as part of the ELEMI program. TM conducted the data collection. TM analysed the data with input from TS, NR, LD and GD. First draft was written by GD, NR and TM and critically appraised by all authors. All authors reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Funding.

Ethics Approval

Obtained from the Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka (Ref. 2025.02.532)

Consent to Participate

Obtained

Consent for Publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 2025; 13(2): e196-e8. [CrossRef]

- Nirmala R GD, Peter P, Tharanga M, Thamudi S, Lanka D. The impact of Natural and Surgical Menopause in the Sri Lankan Population. Plos Blogs; 2025.

- Ananda T, Nahallage C. Present sociocultural status of the Sri Lankan indigenous people (the Veddas) and future challenges. Indigenous People and Nature: Elsevier; 2022: 381-98.

- Deraniyagala, SU. The prehistory of Sri Lanka: an ecological perspective: Harvard University; 1988.

- Welikala A, Desai S, Singh PP, et al. The genetic identity of the Vedda: A language isolate of South Asia. Mitochondrion 2024; 76: 101884. [CrossRef]

- De Silva P, Punchihewa A. Socio-anthropological research project on Vedda community in Sri Lanka. Department of Sociology, University of Colombo, Colombo 2011.

- Bank, W. Indigenous Peoples. 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples#1 (accessed 03.05.2025.

- Ministry of Finance Economic Stabilization & National (MoF) and Ministry of Women CAaSE, (MoWCASE). Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework (IPPF), 2024.

- Kovach, M. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts: University of Toronto press; 2021.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006; 3(2): 77-101. [CrossRef]

- Cowell AC, Gilmour A, Atkinson D. Support mechanisms for women during menopause: perspectives from social and professional structures. Women 2024; 4(1): 53-72. [CrossRef]

- AlSwayied G, Frost R, Hamilton FL. Menopause knowledge, attitudes and experiences of women in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 2024; 24(1): 624. [CrossRef]

- Vazirani A, Ravichandiran N. Prevalence of Menopausal Symptoms and Their Health Seeking Behavior in Postmenopausal Women in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Cancer Research 2024; 9(4): 385-94. [CrossRef]

- Vishwa, S. Vishwa S. Indigenous medical systems and national policy. Daily FT. 2021 Saturday, 29 May 2021.

- Riswan M, Bushra B. The “Veddas” in Sri Lanka: Cultural Heritage and Challenges. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archeology 2020; 8: 573-88.

- Shatilwe JT, Kuupiel D, Mashamba-Thompson TP. Evidence on access to healthcare information by women of reproductive age in low-and middle-income countries: scoping review. Plos one 2021; 16(6): e0251633. [CrossRef]

- Dillaway H. Living in uncertain times: Experiences of menopause and reproductive aging. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies 2020: 253-68. [CrossRef]

- Canada MFo. The Silence and the Stigma: Menopause in Canada: Menopause Foundation of Canada; 2022.

Table 2.

Verbatim quotes linked to individual perceptions of entering menopause.

Table 2.

Verbatim quotes linked to individual perceptions of entering menopause.

“I reached menopause naturally at the age of 50, just as my mother had mentioned it would happen around that time.” (P2, 60 years)

“I first learned about the end of monthly periods from my mother, who told me that after the age of 50, a woman would no longer be able to have children because her periods would stop permanently. Other than what my mother shared, no one else provided us with any information about menopause during those times.” (P1, 49 years)

“I kept all the feelings to myself, hoping they would eventually subside, but they never did.” (P5, 64 years)

“I feel that our time has passed, and these changes are simply a natural part of aging. For me, menopause hasn't brought about particularly good or bad feelings”. (P4, 56 years) |

Table 3.

Verbatim quotes linked to the access to menopausal healthcare services.

Table 3.

Verbatim quotes linked to the access to menopausal healthcare services.

“Having lacked formal education, my understanding of health matters is limited. This has made it difficult for me to access and understand important information, especially about issues like menopause. No one ever provided me with education or guidance about what to expect during this stage of life, so I faced these changes without knowing what was happening to my body or how to manage it.” (P2, 60 years)

“I have never heard about hormone treatment and have not attended any well-woman clinics, as we were never informed about them or encouraged to take part. Without this awareness or support, it has been challenging to seek help or understand the options available for managing my health.” (P1, 49 years)

“However, no one else ever provided me with any education or guidance about menopause or what to expect during this stage of life. Not from the hospital, not from the clinic, not even from the midwife.” (P1, 49 years)

“During my early years, formal education was not accessible to us, as we lived closer to the forests and were not integrated into civil society”. (P5, 64 years)

“Occasionally, I sought treatment at the hospital when the symptoms became severe, but no clear explanations were given to me” (P5, 64 years) |

Table 4.

Verbatim quotes linked to the menopausal experience, their impact including the quality of life.

Table 4.

Verbatim quotes linked to the menopausal experience, their impact including the quality of life.

“Currently, I am experiencing leg and joint pain, along with difficulties sleeping, such as an inability to maintain continuous sleep. I also deal with excessive night sweats, hot flashes, and increased fatigue compared to before. Recently, I’ve been waking up in the middle of the night, feeling chills and experiencing a sensation like electric currents running through my body. While my intimate relationship with my husband has continued, it has shifted somewhat and occasionally feels more challenging.” (P3, 51 years)

“During this time, I dealt with various symptoms, including excessive sleepiness, lethargy, sweating, back pain, leg pain, vision problems, headaches that required treatment, and difficulty performing even simple tasks” (P4, 56 years)

“Even the smallest things made me cry. I was not myself anymore. I felt like I lost control over my body and mind.” (P2, 60 years)

“I feel that our time has passed, and these changes are simply a natural part of aging. I no longer felt like myself”. (P3, 51 years)

“I began to notice significant changes in my physical and emotional state. Tasks and routines I once managed with ease started to feel overwhelming, accompanied by a growing aversion to my usual work. My motivation seemed to drain, replaced by a persistent sense of lethargy toward my responsibilities”. (P1, 49 years)

“I also experienced a loss of interest in sexual activities and began avoiding them entirely. My memory became unreliable, leading to forgetfulness and frustration in daily life. Stress was constant, often manifesting as anger and irritation.” (P1, 49 years)

“I kept all the feelings to myself, hoping they would eventually subside, but they never did. Managing my long-term asthma with inhalers has become increasingly challenging, and I now find it difficult to fully engage in daily chores. However, I try to contribute by helping with smaller tasks”. (P5, 64 years) |

Table 5.

Verbatim quotes linked to coping mechanisms and practices for Practices for Symptom Relief.

Table 5.

Verbatim quotes linked to coping mechanisms and practices for Practices for Symptom Relief.

“As the day progresses, I often feel physically exhausted and experience discomfort after completing my work. To alleviate these symptoms, I’ve been applying balm, taking 'Panadol' tablets, and drinking herbal remedies frequently. These include boiled water infused with “Wenivelget” (Coccineum fenestrstum) bark, “Polpala” (Aerva lanata), and coriander seeds. Occasionally, I also consume boiled water made with another local herbal remedy called "Katuwelbatu" (Solanum virginianum), which is readily available in this area. Using these traditional and herbal remedies helps me feel better”. (P3, 51 years)

“From time to time, traditional practices such as “thowil shanthi” was performed in an attempt to bring relief and improvement to my condition. There were moments when life felt less meaningful, and I attributed these changes to the natural process of ageing. I do not rely on Western medicine, except for inhalers to manage my asthma. Instead, we turn to traditional remedies like “Rasakinda” (Tinospora cordifolia), “Nelli” (Phyllanthus emblica), and “Binkohomba” (Munronia pinnata) to ease physical discomfort and enhance our overall well-being”. (P5, 64 years) |

Table 6.

Verbatim quotes linked to individual adaptation and self-reliance.

Table 6.

Verbatim quotes linked to individual adaptation and self-reliance.

“I have not undergone any local treatment for my health difficulties, but I hold on to the hope that these symptoms will eventually ease and that I will feel better. To relieve my backache, I sleep on the floor and rely on paracetamol to manage my physical symptoms. My husband has been supportive, helping me seek medical care, when necessary, though he is unaware of the connection between the cessation of my periods and the health issues I am facing”. (P1, 49 years)

“But caring for my grandchildren and protecting our crops gives me comfort, it helps me feel that I’m still needed. As an elder, I also take part in rituals that connect me to our community and heritage. Even with the struggles, these moments remind me that my role still matters, and I hold onto that”. (P5, 64 years) |

Table 7.

Verbatim quotes linked to the positive outlook shared by some women.

Table 7.

Verbatim quotes linked to the positive outlook shared by some women.

“Despite the challenges, I find motivation in engaging with work, which gives me a sense of purpose in life. I do not feel any aversion toward life or living; instead, I am open to taking on any kind of work. Emotionally, I neither feel sadness nor happiness, and I have not experienced any significant issues with forgetfulness or anger during my daily activities”. (P3, 51 years)

“I take great pleasure in eating the produce I grow and cultivate myself; it’s deeply rewarding. I feel deep love and affection for my grandchildren, and spending time with them brings me genuine happiness”. (P4, 56 years) |

Table 8.

Verbatim quotes linked to adherence to prescribed treatments.

Table 8.

Verbatim quotes linked to adherence to prescribed treatments.

“Hospital, but I still experience occasional episodes of faintness and weight loss. Although I feel better when I am undergoing treatment, I have difficulty maintaining a regular medication schedule due to both the challenges of managing the routine and the financial burden of out-of-pocket expenses. As a result, I have recently stopped taking my medication”. (P3, 51 years)

“When I seek help, it usually comes only during sudden, overwhelming crises. Otherwise, I rely on paracetamol to ease the frequent pain and discomfort. Sometimes I seek advice from the area midwife, hoping for guidance amidst these challenges”. (P2, 60 years)

|

Table 9.

Verbatim quotes linked to the psychological impact of menopause.

Table 9.

Verbatim quotes linked to the psychological impact of menopause.

“In our community, being born female often feels like a misfortune compared to being male, as we bear heavy burdens such as childbearing, caring for children as a widowed mother, and enduring menstruation. At times, the weight of these hardships has led me to contemplate ending my life as a way out, though I have never acted on those thoughts. Sometimes, I feel that being a woman is a curse. We suffer throughout our lives, from periods to menopause”. (P2, 60 years)

“I feel like I’m no longer a woman. Everything has changed. My body, my desires, my energy it’s all gone.” (P4, 56 years)

“My children and husband were unaware of what I was going through, as I didn’t take it seriously enough to discuss it with them. These unspoken struggles were heavy, but they became part of my journey and resilience”. (P5, 64 years)

“At times, I question why I’m still here, especially when I don’t have the strength to keep going. These thoughts weigh on me, and there’s no one to share them with or help lighten the load”. (P5, 64 years) |

Table 10.

Verbatim quotes linked to barriers in healthcare access.

Table 10.

Verbatim quotes linked to barriers in healthcare access.

“I live far from the hospital. Even if I go, they don’t give importance to menopause. They just say it’s normal.” (P2, 60 years)

“For even basic medical care, we have to walk a minimum of 6 kilometers. If specialized care is required, we need to travel to Bibile Hospital, a rural hospital, which adds further strain on our capabilities”. (P2, 60 years)

“Accessing healthcare remains a significant challenge for us. The health facilities are located far from our village, and traveling to them is difficult due to a lack of transportation and financial resources”. (P2, 60 years)

“I always hesitated to seek help at the hospital, convinced that my unusual symptoms would never be taken seriously. It felt as though being older meant my concerns were dismissed outright, regarded as insignificant or unworthy of attention.” (P5, 64 years) |

Table 11.

Verbatim quotes linked to community level gaps and emerging trends.

Table 11.

Verbatim quotes linked to community level gaps and emerging trends.

“So far, I haven't sought any special treatments apart from using contraception implants, which were supported by the area midwife (PHM). Our midwife talks about pregnancy and children, but never about menopause. It’s as if it doesn’t exist for them. I have not attended the Well-Woman Clinic yet”. (P4, 56 years)

Participants expressed a desire for establishing a dedicated healthcare center and suggested integrating menopause-related information through it.

“It would be incredibly beneficial for our village to have access to both information and a primary healthcare center nearby”. (P4, 56 years)

“The thought of having a hospital or healthcare facility nearby feels like a distant yet vital need. Government and non-government organizations have visited us, but they rarely return to offer ongoing support or address our problems”. (P1. 49 years) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).