Background

Menopause represents a significant biological and social transition in a woman’s life, marking the end of reproductive capacity and bringing with it a range of physical, psychological, and socio-cultural changes [

1,

2]. In Rwanda, menopause has received limited attention within public health agendas, despite its profound implications for women’s health and wellbeing [

3]. Women often experience vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats, musculoskeletal pain, sleep disruption, mood changes, and urogenital concerns, all of which can affect quality of life and daily functioning [

4,

5,

6]. These symptoms can be particularly challenging in contexts where physical labour is a key part of survival and economic contribution, such as farming and tailoring, which are common livelihoods for women across the country. However, in Rwanda, menopause is often viewed as a private and inevitable stage of life rather than a clinical or public health concern [

7]. Cultural expectations emphasise endurance and silence, which can prevent women from seeking help or even discussing their experiences with peers or health professionals. This silence contributes to missed opportunities for early intervention and support. Without accessible, culturally sensitive services, many women are left to manage symptoms alone, often relying on spiritual coping or informal remedies [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, menopause becomes an invisible issue within the health system, despite its far-reaching effects on women’s physical and emotional health, social roles, and economic productivity [

12,

13,

14].

Rwanda’s population dynamics make understanding and addressing menopause increasingly urgent. The country has a growing population of midlife and older women, with life expectancy steadily rising due to improvements in healthcare and reductions in maternal and infectious disease mortality [

15,

16,

17]. As the population ages, the number of women experiencing menopause and its associated challenges will continue to increase. Rural areas, where the majority of women reside, face unique barriers including limited access to health facilities, transport challenges, and financial constraints that hinder care-seeking. These structural inequities intersect with socio-cultural factors to exacerbate health disparities, leaving rural women particularly vulnerable. Although reliable national data on menopause prevalence are lacking, global estimates suggest that nearly every woman who lives into midlife will experience menopause, with many reporting moderate to severe symptoms. In Rwanda, where reproductive health policies historically prioritised maternal health and family planning, menopause has been overlooked, resulting in significant gaps in service provision and policy planning. The consequences extend beyond individual health: unmanaged menopause symptoms can reduce women’s participation in the workforce, limit their ability to contribute to household economies, and increase their risk of chronic conditions such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. This has implications for families, communities, and the broader national economy. Addressing menopause is therefore not only a matter of individual wellbeing but also a vital component of Rwanda’s strategy to manage the needs of an ageing population and promote health equity.

Rationale

Despite the universal nature of menopause, it remains under-researched and under-represented in both clinical practice and policy frameworks in Rwanda. The absence of national data means that health systems lack the evidence needed to design services that reflect women’s lived experiences and address their specific needs. While reproductive health programmes have made notable progress in reducing maternal and infant mortality, there has been little focus on women’s health beyond childbearing years. This study was undertaken to fill that critical gap. It seeks to capture the diverse experiences of women across natural, surgical, and medical menopause, exploring how biological symptoms intersect with psychological, socio-cultural, health-system, and structural determinants. By examining these factors, the study provides a comprehensive picture of how menopause is navigated within Rwandan communities and health systems. Understanding these experiences is essential for several reasons as it offers insights into the hidden burden of menopause on women’s lives, inequities between rural and urban women, including its impact on productivity, mental health, and relationships. It also provides policymakers and health professionals with actionable evidence to design culturally sensitive interventions that break down stigma and silence. This study contributes to the growing global conversation on midlife and ageing women’s health, positioning Rwanda as part of a wider effort to address a historically neglected area. By doing so, it supports the development of integrated, life-course approaches to women’s health that recognise menopause as a key stage requiring attention, investment, and inclusion in national health planning. Ultimately, this research aims to ensure that women in Rwanda are not left to face menopause in isolation but are supported through informed policy, strengthened services, and community-driven solutions.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This qualitative study was part of the MARIE Rwanda Work Package 2a (WP2a) and was designed to explore the lived experiences of women undergoing perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause. It was conducted across both rural and urban regions of Rwanda, representing women from diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The study forms part of a wider multi-country initiative aimed at deepening understanding of women’s health and ageing.

The Delanerolle and Phiri theory and framework were applied to guide both the data collection and analysis [

18]. This framework allowed exploration across five interconnected domains: biological, psychological, socio-cultural, health-system, and structural or environmental. By applying this approach, the analysis captured the complex interplay between individual experiences and broader societal and health-system factors influencing natural, surgical, and medical menopause.

Participant Recruitment and Sampling

Participants were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling to ensure a range of perspectives across age, menopausal stage, socio-economic status, and geographical location. Women were eligible to take part if they were aged between 40 and 75 years and had experienced menopause naturally, surgically, or medically. Those with severe cognitive impairment or other conditions that would prevent meaningful participation were excluded.

In total, 28 interviews were included in the final analysis. The sample included women from farming communities, urban households, and professional roles such as teaching and healthcare. This diversity reflected the broad demographic and occupational contexts of Rwanda and ensured that findings captured a wide range of experiences.

Data Collection

Data were gathered through in-depth interviews conducted in Kinyarwanda. The interview guide was co-developed with local health professionals, researchers, and women with lived experience to ensure cultural sensitivity and contextual relevance. Questions explored biological symptoms, psychological wellbeing, socio-cultural beliefs, health-seeking behaviours, interactions with the health system, and structural challenges.

Interviews were conducted in private, comfortable locations chosen by participants, such as their homes or community centres. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim into Kinyarwanda. The transcripts were then translated into English by trained bilingual researchers. Back-translation was carried out by independent linguists to confirm accuracy and cultural fidelity. Field notes were kept throughout the data collection period to capture non-verbal communication, environmental factors, and researcher reflections.

Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda (CMHS-UR Institutional Review Board: No. 207/CMHS IRB/2025). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were assured of confidentiality, anonymity, and their right to withdraw at any point without consequence. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ghanaian research governance guidelines. Researchers were trained in culturally sensitive, trauma-informed interviewing techniques given the sensitivity of discussing menopause and healthcare experiences.

Data Management and Analysis

The analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis, integrated with the domains of the Delanerolle and Phiri framework. The process began with immersion in the data, where researchers read and re-read transcripts and field notes to gain a deep understanding of the material. Initial codes were then generated inductively from the data, while simultaneously mapping them to the five domains of the framework.

Codes were organised into potential themes and sub-themes to capture recurrent patterns across participants’ experiences. These themes were then examined in relation to determinants and exposures, exploring how factors such as socio-cultural norms or structural barriers influenced the impact of menopause. The research team collaboratively refined the themes to ensure they were clear, coherent, and accurately reflected the data. Contextual mapping was used to situate these themes within broader societal and health-system structures, illustrating the interconnections between biological, psychological, cultural, and structural influences.

Rigour and accuracy were ensured by bilingual analysts who cross-checked transcripts and interpretations. Verbatim quotes were carefully translated, and idiomatic expressions were reviewed in team meetings to maintain their original meaning. A colloquial analysis table was developed to document key menopause-related terms in both Kinyarwanda and English, helping to preserve linguistic and cultural nuance.

Finally, community validation workshops were conducted with participants and local stakeholders. These sessions allowed for confirmation of the findings’ accuracy and ensured that the thematic interpretations resonated with the lived experiences of the women involved.

Adherence to COREQ Guidelines

This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline to ensure transparency and methodological rigour.

Results

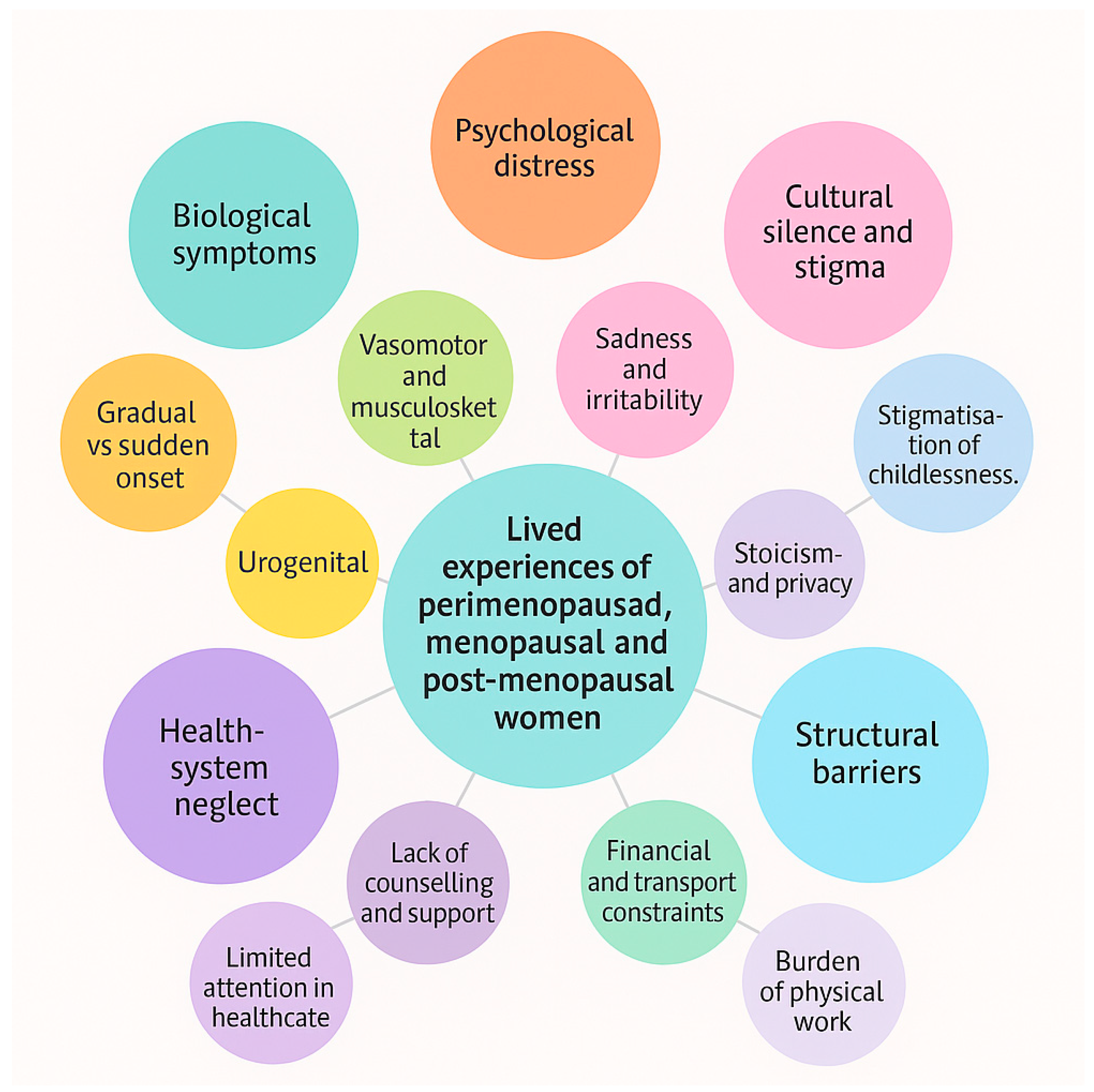

We analysed 28 interviews spanning natural, surgical, and medical menopause across rural and urban Rwanda. Experiences clustered into five interlocking themes: (1) biological symptom load and functional loss; (2) psychological disequilibrium and coping; (3) socio-cultural silence and norms; (4) health-system invisibility of menopause; and (5) structural frictions in work, transport, and cost. Symptom acuity was greatest in surgical and illness-linked trajectories, while a minority of women described more moderate, “endure and carry on” courses shaped by normalisation and low expectations. These patterns were consistent across occupations (farming, tailoring, teaching, hospital work) but intensified where physical labour and travel were routine (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

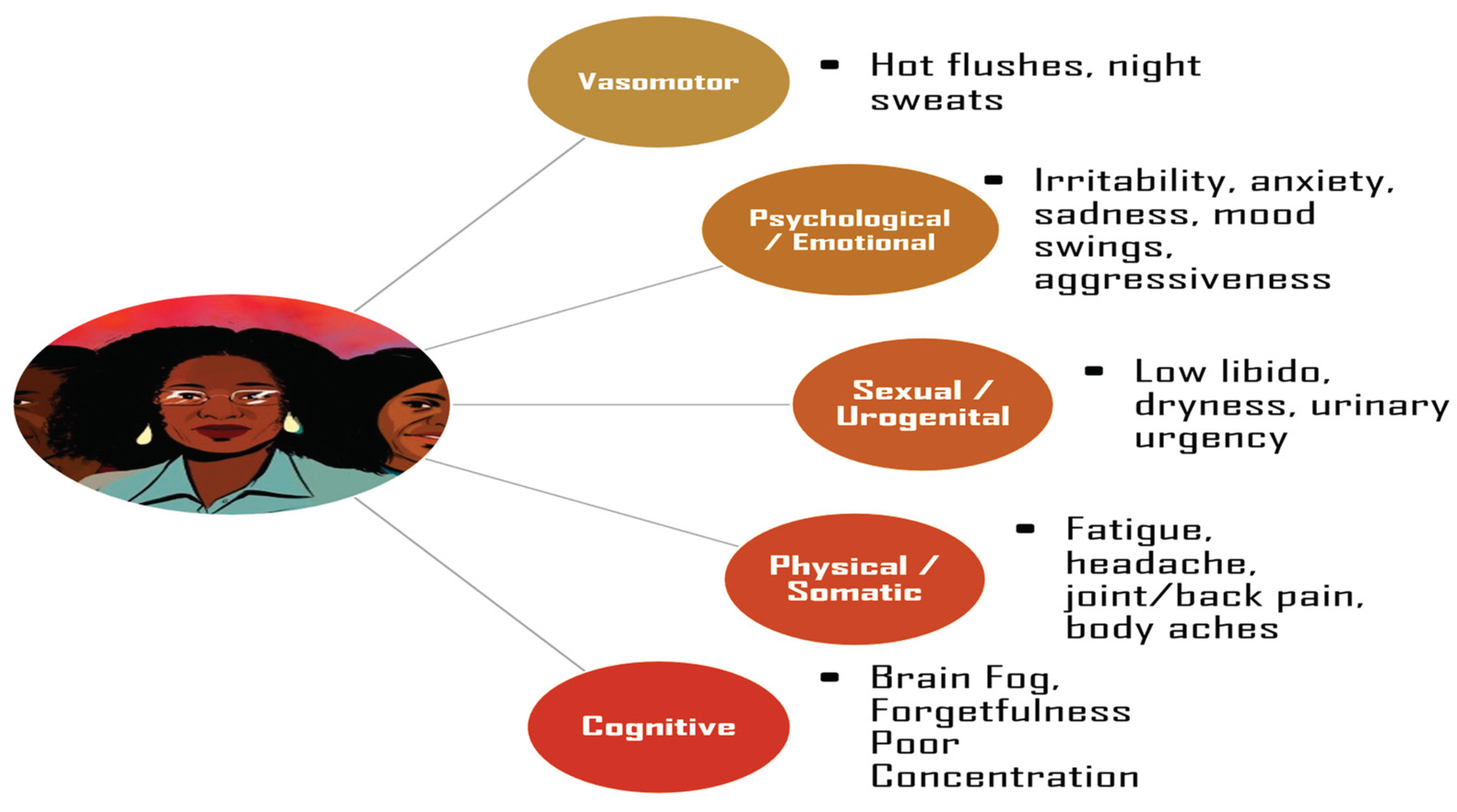

Theme 1: Biological Symptom Load and Functional Loss

Across accounts, vasomotor symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, pelvic discomfort and sleep disruption translated directly into reduced work capacity at the farm, sewing table, or clinic floor. Surgical menopause produced the most abrupt deterioration, often described as a “suddenness” that outpaced women’s ability to adapt (

Figure 2).

“Since the operation and menopause, my stress feels much higher.”

(PID06)

“The suddenness after surgery made it worse.”

(PID05)

“I cannot work as long as I used to.”

(PID02)

“Joint pain makes it hard to sit long at the sewing machine.”

(PID07)

“Hot flashes disturb me at night.”

(PID01)

Theme 2: Psychological Disequilibrium, Sleep Loss and Coping

Sleep fragmentation and unmanaged pain magnified irritability, sadness, hopelessness and cognitive fog. Women described crying, withdrawal, and fear that life would not return to normal. Faith, prayer and sister-to-sister talk were common coping strategies but could not substitute for structured support.

“Some days I wake up and wonder if life will ever feel normal again.”

(PID06)

“I feel low most of the time and cry easily.”

(PID08)

“Sometimes I feel irritated for no reason.”

(PID03)

“Some days I feel like I cannot manage.”

(PID02)

“Prayer gives me comfort.”

(PID03)

Theme 3: Socio-Cultural Silence, Expectations and Identity

Menopause was widely framed as private and to be borne “strongly,” muting help-seeking and peer learning. Expectations around motherhood sharpened stigma for women without children; some equated this with judgement and altered identity.

“Women are told to stay strong and silent.”

(PID07)

“In my culture people don’t talk about these things.”

(PID08)

“There is pressure on women to have children.”

(PID05)

“Women don’t openly talk about menopause.”

(PID01)

Theme 4: Health-System Invisibility and Missed Opportunities

Across settings including hospitals menopause was rarely asked about, with encounters reduced to blood pressure or glucose checks. This invisibility delayed recognition, normalised suffering, and left surgical or cancer-affected women without anticipatory counselling.

“They check my blood pressure but not menopause.”

(PID02)

“Menopause is not discussed enough, even among us.”

(PID05)

“Doctors don’t ask much about menopause.”

(PID01)

“They treat my cancer but no one asks about my feelings.”

(PID08)

“They didn’t give me much counselling after the surgery.”

(PID06)

Theme 5: Structural Frictions—Work, Distance, and Cost

Distance to clinics, transport costs, and the physical demands of daily labour compounded symptoms and constrained care-seeking. Where income depended on daily sales or farm work, women deferred appointments and “carried on,” entrenching a cycle of fatigue and foregone care.

“Transport is difficult and medicine is expensive.”

(PID07)

“The cost is very high, and traveling to the hospital is not easy.”

(PID08)

Women from rural areas described the double burden of physical strain and poor access to care:

“I cannot work as long as I used to, but if I rest, there will be no food for the family.”

(PID02)

“Farm work worsens the pain, yet I cannot afford to stay at home.”

(PID21)

In several accounts, clinic visits required long journeys on foot or by motorbike, deterring women from seeking help unless symptoms became unbearable:

“The clinic is far and I have to walk; by the time I arrive, I am already exhausted.”

(PID04)

“Sometimes I want to go for a check-up, but I think of the distance and the fare and decide to stay.”

(PID27)

Economic insecurity further intensified the dilemma between earning an income and caring for one’s health:

“If I go to the hospital, I lose the day’s money. So, I just buy herbs and continue working.”

(PID06)

“Maybe if I had another source of income, I would rest more or go to the doctor.”

(PID21)

These structural barriers not only delayed care-seeking but also deepened emotional and physical exhaustion, reinforcing gendered inequalities in access to health services. The combined weight of financial strain, transport limitations, and physically demanding labour created a silent but persistent constraint on women’s ability to prioritise their own wellbeing. Addressing these systemic frictions requires decentralised service delivery, affordable medication, and flexible community-based outreach to make menopausal care accessible for all women, regardless of geography or income.

Contrasts and Deviant Cases

A minority described a more moderate course, often framed as a “natural process” requiring little formal help. Even here, women wanted clearer information to prepare and normalise symptoms.

“Menopause is a natural process.”

(PID10)

“Except for the unusual fatigue, nothing much changed.”

(PID12)

“I would like more explanation about menopause symptoms.”

(PID10)

Experiences of menopause varied considerably between women with natural transitions and those whose menopause was surgically or medically induced. Women experiencing natural menopause described a gradual escalation of symptoms, often framing the process as a natural stage of life. They relied primarily on self-care, herbal remedies, and prayer, reflecting both normalisation and limited formal service engagement. A housewife explained:

“Menopause is a natural process. Except for the unusual fatigue, nothing much changed, but I would like more explanation about menopause symptoms.”

(PID10)

Similarly, another woman from a rural farming background stated:

“Knowing beforehand would have prepared me mentally. I was not ready for these changes.”

(PID11)

In contrast, surgical and medical menopause was characterised by abrupt, severe symptom onset, often following hysterectomy or cancer treatment. Women spoke of shock, loss of bodily control, and intense distress in the absence of anticipatory counselling. A participant who underwent a hysterectomy described:

“The suddenness after surgery made it worse. The hot flashes and mood swings can be overwhelming.”

(PID05)

Another, managing both menopause and cancer, shared:

“I feel low most of the time and cry easily. Even small tasks feel too hard for me now.”

(PID08)

These women were acutely aware of systemic neglect, noting that physical healing was prioritised over emotional or reproductive wellbeing:

“They didn’t give me much counselling after the surgery. It was only about wounds, not about how I was feeling inside.”

(PID06)

Geographical context further shaped experiences. Women living in rural areas faced substantial structural barriers to care, including distance, lack of transport, and financial constraints. These compounded biological and psychological burdens, often resulting in delayed or foregone care. A farmer explained:

“Transport is difficult and medicine is expensive. Sometimes I just stay home and endure the pain.”

(PID07)

For rural women engaged in heavy farm work, physical exertion amplified symptom severity:

“I leak urine when I cough or lift heavy things. This makes farm work very hard.”

(PID02)

In contrast, urban participants generally reported fewer access barriers, though gaps in service quality persisted. Even among hospital workers, menopause remained invisible within the health system. A participant working in a hospital shared her frustration:

“Menopause is not discussed enough, even among us as health workers. There is no guidance.”

(PID05)

Urban women with higher education levels often sought more detailed information but still encountered dismissive attitudes:

“They check my blood pressure but not menopause. No one asks about these changes.”

(PID02)

Occupational differences shaped how women experienced and coped with menopause. Farmers and women in heavy physical labour described being physically “worn out,” with symptoms directly undermining productivity. One woman explained:

“My body gets tired very quickly now. I cannot keep up with the farm as before.”

(PID02)

Tailors experienced a different type of strain from prolonged sitting and repetitive movements. A tailor noted:

“Joint pain makes it hard to sit long at the sewing machine, and it slows my work.”

(PID07)

Among teachers and professionals, the focus was on cognitive impacts and performance. A teacher reported:

“Sometimes I feel foggy during lessons. It is hard to keep track, and I worry about making mistakes in front of my students.”

(PID12)

Healthcare workers faced the paradox of being within the system yet lacking menopause-sensitive support. A hospital employee highlighted this:

“Long shifts exhaust me, and symptoms get harder to manage when there is no understanding from colleagues.”

(PID05)

Contextual Analysis

The experiences of Rwandan women navigating perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause reveal a deeply interconnected set of biological, psychological, socio-cultural, health-system, and structural factors.

Women undergoing natural menopause typically described a gradual emergence of symptoms, including hot flushes, fatigue, pelvic and joint pain, and disrupted sleep. These changes were often perceived as part of normal ageing and endured quietly through self-care practices and spiritual coping. This acceptance provided some emotional resilience but also contributed to low visibility within health services. While these women rarely sought medical support, they expressed a desire for better education and anticipatory guidance to understand and manage their symptoms. In contrast, surgical and medical menopause followed a much more abrupt and severe trajectory. Women who experienced menopause as a result of hysterectomy or cancer treatment described sudden and overwhelming changes, both physically and emotionally. Without prior counselling or preparation, they reported feeling shocked, unprepared, and unsupported. The absence of tailored post-surgical and post-treatment care intensified distress and disrupted recovery, leaving women to manage profound bodily changes alone.

Psychological challenges were evident across all groups but were most pronounced in women facing abrupt surgical or medical transitions. Poor sleep, unmanaged pain, and lack of professional support were closely linked to sadness, irritability, and hopelessness. Many women relied on informal coping mechanisms such as faith, prayer, and discussions with trusted friends or relatives. These strategies provided some comfort but could not fully address the need for structured psychological care and counselling.

Cultural expectations played a critical role in shaping experiences. Menopause was commonly viewed as a private matter that should be endured silently. This societal framing discouraged open dialogue and reinforced isolation, preventing women from learning from one another or collectively challenging stigma. For those who had not borne children, deeply embedded social norms around motherhood heightened feelings of exclusion and shame. Structural factors further influenced access to care and symptom management. Rural women faced substantial barriers, including long distances to health facilities, high transportation costs, and limited financial resources. These barriers often resulted in delayed care or complete reliance on home-based remedies. The physical demands of farming and other forms of manual labour intensified symptoms and reduced productivity, threatening household income and stability. In urban areas, physical access to services was less problematic, but women encountered subtler forms of neglect within health facilities, where menopause remained largely absent from clinical discussions and care pathways.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that women’s experiences of menopause are shaped by a web of intersecting factors. Addressing these challenges requires integrated, culturally sensitive care that includes education, counselling, and community support while also addressing the broader structural and systemic inequities that affect women’s health outcomes. To support this fact summarised verbatim quotes are included in

Table 2.

Colloquial Analysis

In the Rwandan context, menopause is often spoken about using indirect and culturally nuanced language. Terms describing symptoms are rooted in everyday experiences, such as heat or tiredness, rather than clinical terminology (

Table 3 and

Table 4). Hot flushes are commonly referred to as “feeling fire inside,” while fatigue is described as “the body being heavy.” Emotional changes are framed around strength and resilience, with sadness or anxiety seldom openly named but implied through references to “thinking too much” or “carrying a heavy heart.” Silence around menopause reflects societal expectations for women to endure quietly, reinforcing privacy, stigma, and limited peer-to-peer discussions.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that menopause in Rwanda is a multifaceted experience shaped by biological, psychological, socio-cultural, health-system, and structural determinants. The results highlight profound variation between women undergoing natural menopause and those experiencing surgical or medical menopause. Natural menopause was often understood as a gradual, expected transition, with symptoms such as hot flushes, pelvic and joint pain, fatigue, and disrupted sleep endured quietly and managed through self-care practices and spiritual coping. In contrast, surgical and medical menopause was abrupt and intense, often linked to hysterectomy or cancer treatment, leaving women unprepared and distressed in the absence of anticipatory counselling or emotional support. Across all groups, menopause was framed as a private matter, and societal expectations of stoicism contributed to silence, stigma, and isolation. These cultural norms, combined with limited knowledge, reinforced a lack of open dialogue and constrained opportunities for shared learning or collective advocacy. Structural and systemic factors compounded these experiences. Rural women faced the greatest barriers, including geographical distance to health facilities, unaffordable transport costs, and reduced access to medication, which often resulted in delayed or foregone care. In urban settings, physical access to clinics was less problematic, yet subtle neglect persisted, with menopause rarely addressed in routine consultations even for women working within the health system. Together, these findings illustrate a cycle of invisibility: biological symptoms lead to psychological strain, which is exacerbated by cultural silence, systemic neglect, and structural barriers, resulting in an overwhelming burden on women that remains largely hidden.

Population Implications

When viewed through the lens of population science, the findings highlight significant gaps in how menopause is addressed within health systems and communities. With Rwanda’s population ageing, the number of women experiencing menopause is set to increase substantially in the coming years, making this an urgent public health issue. Despite this, menopause remains absent from most population-level health initiatives and clinical monitoring frameworks. The lack of reliable data on prevalence, symptom burden, and associated health risks contributes to its continued marginalisation. The disparities identified between rural and urban women highlight structural inequities that are likely to widen as demographic transitions progress. Rural women face a double disadvantage: limited physical access to services and heavy reliance on physically demanding labour that worsens symptoms and reduces productivity. These challenges have economic implications for households and communities, as reduced work capacity directly affects livelihoods and food security. Urban women, while physically closer to services, encounter institutional neglect and lack of recognition of menopause in clinical settings, underscoring that access alone is insufficient without quality, tailored care. Addressing these issues requires integrating menopause into broader population health surveillance and ensuring it is considered within health system strengthening efforts. This includes recognising menopause not only as a clinical issue but as a socio-economic determinant of women’s health and wellbeing across the life course.

Clinical and Policy Implications

From a clinical perspective, the findings reveal significant gaps in both knowledge and practice. Health workers often focus on conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, with menopause rarely addressed during consultations. Even in hospitals, women described how clinicians failed to acknowledge or manage menopausal symptoms. Surgical and medical menopause, in particular, represent missed opportunities for intervention. Women undergoing hysterectomy or cancer treatment did not receive counselling or follow-up care to prepare them for abrupt symptom onset. This gap is especially concerning given the heightened psychological and physical burden faced by these women. Clinicians require training to recognise menopause as a significant health event, to integrate anticipatory guidance into surgical and oncology pathways, and to provide holistic, patient-centred care. From a policy perspective, the invisibility of menopause in national health strategies perpetuates systemic neglect. Without explicit inclusion in policies and resource allocation, services will remain fragmented and underdeveloped. Incorporating menopause into reproductive health and ageing agendas is vital for addressing current gaps. Policymakers should also consider interventions at community level, such as peer support groups and educational campaigns, to break down stigma and cultural silence. Furthermore, financial and structural barriers, particularly for rural women, must be addressed through transport vouchers, mobile outreach services, and coverage of essential medications. This multi-level approach would ensure that menopause is recognised not only within clinical care but also as part of a comprehensive public health response. The

Table 5 implies the recommendations for the current issues.

Conclusion

This study provides critical insight into how menopause is experienced by women in Rwanda, revealing profound intersections between biological, psychological, cultural, and structural factors. It highlights how natural menopause is often normalised, while surgical and medical menopause is abrupt and distressing, leaving women unprepared and unsupported. The findings underscore the urgent need to integrate menopause into population health strategies, clinical pathways, and policy agendas. Addressing these gaps requires tailored interventions that combine education, stigma reduction, and systemic change to ensure equitable and accessible care. By recognising menopause as a key component of women’s health, Rwanda can take a decisive step towards improving quality of life and promoting health equity for midlife and older women.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda (CMHS-UR Institutional Review Board: No. 207/CMHS IRB/2025).

Consent to participate

Participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Author Contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. DCI submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study in Ghana. DCI and team recruited participants to the study. GD and JQS conducted the data analysis. GD and DCI wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors DCI, GJP, KC, NHC, SMI, JDH, KJMV, DU, MM, AK, ET, EH, JS, VP, JT, LS, SH, KP, KE, CA, VT, GUE, OK,NR, TM, JD, LA, NA, BM,IM, FT,NM, THT,PKM,MI,RK,CLB,HFK, RP, JS,NP,SE,PP,GD critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

MARIE Consortium: Donatella Fontana, Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Rukshini Puvanendram, Manisha Mathur, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Farah Safdar, Raksha Aiyappan, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Bertin Ngororano, Victor Archibon, Ibe Michael Usman, Baraka Godfrey Mwahi, Filbert Francis Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Clement Mwabenga, Mpoki Kaminyoghe, Brenda Mdoligo, Thomas Alone Saida, Nicodemus E. Mwampashi, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Delanerolle, G.; Phiri, P.; Elneil, S.; Talaulikar, V.; Eleje, G.U.; Kareem, R.; Shetty, A.; Saraswath, L.; Kurmi, O.; Benetti-Pinto, C.L.; et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e196–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston, R.C.; Thomas, H.N.; Castle, A.J.; Gibson, C.J. Menopause as a biological and psychological transition. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 4, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitini, B.; Ntihinyurwa, P.; Ntirushwa, D.; Mafende, L.; Small, M.; Rulisa, S. Prevalence, impact and management of postmenopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women in Rwanda. Climacteric 2023, 26, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Téllez C, Cortés-Bonilla M, Ortiz-Luna G, et al. Quality of life and menopause. Quality of Life-Biopsychosocial Perspectives: IntechOpen; 2020.

- Comparetto, C.; Borruto, F. Treatments and Management of Menopausal Symptoms: Current Status and Future Challenges. OBM Geriatr. 2023, 07, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, S.S.; Tayade, S.; Lohiya, N.; Tyagi, A.; Chauhan, A. Menopause dynamics: From symptoms to quality of life, unraveling the complexities of the hormonal shift. Multidiscip. Rev. 2025, 8, 2025057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matina, S.S.; Cohen, E.; Mokwena, K.; Mendenhall, E. Menopause and aging in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Climacteric 2025, 28, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, M.K.; Lock, M.; Kaufert, P. Culture and symptom reporting at menopause. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2005, 11, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.; Callister, L.C.; Berry, J.A.; Matsumura, G. Meanings of menopause: cultural influences on perception and management of menopause. J. Holist. Nurs. 2007, 25, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M. Culturally responsive care for menopausal women. Maturitas 2024, 185, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanzel, K.A.; Hammarberg, K.; Fisher, J. Experiences of menopause, self-management strategies for menopausal symptoms and perceptions of health care among immigrant women: a systematic review. Climacteric 2018, 21, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, G.D.; Davies, M.C.; Hillman, S.; Chung, H.-F.; Roy, S.; Maclaran, K.; Hickey, M. Optimising health after early menopause. Lancet 2024, 403, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafaie, F.S.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Jafari, M. Effect of Education through Support Group on Early Symptoms of Menopause: a Randomized Controlled Trial. 2014, 3, 247–256. [CrossRef]

- A Lobo, R.; Gompel, A. Management of menopause: a view towards prevention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amberbir, A.; Cyuzuzo, C.; Boah, M.; Uwinkindi, F.; Kalinda, C.; Yohannes, T.; Isano, S.; Ojiambo, R.; A Greig, C.; Davies, J.; et al. Understanding needs and solutions to promote healthy ageing and reduce multimorbidity in Rwanda: a protocol paper for a mixed methods, stepwise research study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabates-Wheeler, R.; Wylde, E.; Aboderin, I.; Ulrichs, M. The implications of demographic change and ageing for social protection in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from Rwanda. J. Dev. Eff. 2020, 12, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boah, M.; Cyuzuzo, C.; Uwinkindi, F.; Kalinda, C.; Yohannes, T.; Isano, S.; Greig, C.; Davies, J.; Hirschhorn, L.R.; Amberbir, A. Health and well-being of older adults in rural and urban Rwanda: epidemiological findings from a population based cross-sectional study. J. Glob. Heal. 2025, 15, 04108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women's Health Research. 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).