Background

Menopause marks a major biological transition in a woman’s life, signalling the end of reproductive capacity and introducing a range of physiological, psychological, and social changes [

1,

2]. Globally, women experience a variety of symptoms during this stage, including vasomotor disturbances such as hot flushes and night sweats, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disruption, mood changes, and urogenital symptoms [

3,

4]. These symptoms can significantly affect quality of life, daily functioning, and economic participation, particularly for women engaged in physically demanding work [

5,

6]. In Rwanda, where many women are involved in subsistence farming, tailoring, and informal labour, the burden of these symptoms can limit productivity and threaten household stability. Despite its widespread impact, menopause remains a largely hidden issue in Rwanda, where it is often regarded as a private and natural process rather than a health condition requiring clinical attention [

7,

8]. Cultural expectations encourage women to endure symptoms silently, while societal norms discourage open discussion. This silence perpetuates stigma and isolates women at a time when they may be struggling physically and emotionally. As a result, menopause is rarely addressed in conversations with family, peers, or healthcare providers, leaving women without access to accurate information, guidance, or supportive services.

The Rwandan healthcare system has achieved considerable success in several areas of public health, particularly maternal and child health, family planning, infectious disease control, and increasingly, the management of non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [

9,

10]. However, services remain predominantly focused on reproductive and maternal health, with limited recognition of the health needs of midlife and older women. Menopause is largely absent from national health policies, clinical protocols, and routine service delivery [

8,

11]. Access to care is shaped by geography, socio-economic status, and the availability of trained staff. Rural women face particularly severe challenges, including long distances to health facilities, poor transport infrastructure, and unaffordable costs, which often prevent them from seeking care altogether [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Even when rural women do reach services, shortages of medicines and healthcare workers can undermine the quality and continuity of care. In contrast, urban women generally face fewer physical barriers but encounter systemic neglect, as clinics and hospitals prioritise disease-specific programmes and fail to integrate menopause into their service frameworks [

11,

13]. Community health workers play a pivotal role in Rwanda’s health system, yet their remit is largely confined to maternal and child health, leaving a significant gap in outreach, education, and support for midlife health [

16,

17,

18]. This structural context results in widespread under-diagnosis, poor symptom management, and missed opportunities for intervention.

Critically, the neglect of menopause in Rwanda reflects a wider global pattern where women’s health beyond the reproductive years has been historically marginalised. While maternal health has benefited from decades of investment and targeted programmes, menopause has remained largely invisible in research, funding, and policy-making. A lack of local data on prevalence, symptom burden, and health impacts compounds this problem, making it difficult for governments to plan services or allocate resources effectively. In Rwanda, the absence of surveillance systems means that menopause-related needs are not systematically monitored or addressed [

19]. This creates a cycle where symptoms remain unmanaged, women delay seeking care, and healthcare providers remain unaware of the scale of the issue. Rural–urban disparities exacerbate these inequities, with rural women excluded through structural barriers to access and urban women excluded through systemic neglect despite proximity to services. Without intervention, these gaps will continue to grow as Rwanda’s population ages, placing increasing pressure on families, communities, and the healthcare system [

20,

21].

Rationale

This study was undertaken to address a critical gap in understanding menopause and health-system readiness in Rwanda. While global literature has highlighted the challenges of managing menopause, there has been little exploration of how these issues manifest in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Rwanda’s health system has successfully scaled up maternal and reproductive health services, yet the transition from reproductive to post-reproductive care remains poorly defined. Women’s health after childbearing years has been neglected, resulting in fragmented, disease-focused services that fail to address holistic needs. By using qualitative methods, this study captures the lived experiences of Rwandan women navigating menopause, with a specific focus on how healthcare services respond to their needs. It examines barriers to access, disparities between rural and urban populations, gaps in service provision, and the absence of anticipatory care for women undergoing surgical or medical menopause. This approach provides rich, contextualised evidence that moves beyond symptom descriptions to explore the systemic and structural factors influencing care. By highlighting missed opportunities for intervention, this research addresses a longstanding knowledge gap and supports the development of integrated, life-course approaches to women’s health. In doing so, it aims to position menopause as a priority within Rwanda’s health agenda, ensuring that midlife and older women are no longer left to face this transition alone but are supported through education, outreach, and responsive, accessible care.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This qualitative study formed part of the MARIE Rwanda Work Package 2a (WP2a), a multi-country initiative aimed at understanding menopause and midlife women’s health within diverse global contexts. The Rwanda component focused specifically on women’s experiences of health-system readiness and responsiveness to menopause. The study was conducted across rural and urban regions, capturing perspectives from communities with varying access to healthcare services.

The Delanerolle and Phiri framework [

22] was used to guide data collection and analysis, providing a lens through which menopause could be examined across five interconnected domains: biological, psychological, socio-cultural, health-system, and structural/environmental. This ensured a holistic exploration of women’s journeys through natural, surgical, and medical menopause, with particular attention paid to interactions with healthcare services and system-level challenges.

Participant Recruitment and Sampling

Participants were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling to ensure diversity in age, menopausal stage, socio-economic background, and geographical location. Women were eligible to participate if they were aged 40–75 years and had experienced natural, surgical, or medical menopause. Those with conditions preventing meaningful participation, such as severe cognitive impairment, were excluded.

In total, 28 women were interviewed in Kinyarwanda, representing both rural and urban settings and a range of occupations, including farming, tailoring, teaching, and hospital-based roles. This diversity allowed exploration of how system-level factors varied across different contexts and care environments.

Data Collection

Data were collected through in-depth interviews conducted in Kinyarwanda, guided by a semi-structured topic guide co-developed with local researchers, clinicians, and women with lived experience. The guide included open-ended questions exploring participants’ experiences of menopause, interactions with health services, barriers to care, and perceptions of provider responsiveness. In line with COREQ guidelines, all interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim in Kinyarwanda, and subsequently translated into English by bilingual research assistants trained in qualitative methods. To ensure accuracy, translations were independently reviewed by a second bilingual reviewer, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Back-translation and cross-checking of a random subset of transcripts were performed to maintain linguistic fidelity, cultural nuance, and conceptual equivalence between the source and translated texts.

Interviews were conducted in private, comfortable settings chosen by the participants, such as homes or community spaces, to promote open and safe dialogue. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English by trained bilingual researchers. To ensure accuracy and cultural fidelity, back-translation was performed by independent linguists. Field notes were used to capture contextual observations and non-verbal cues.

Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda (CMHS-UR Institutional Review Board: No. 207/CMHS IRB/2025). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were assured of confidentiality, anonymity, and their right to withdraw at any point without consequence. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ghanaian research governance guidelines. Researchers were trained in culturally sensitive, trauma-informed interviewing techniques given the sensitivity of discussing menopause and healthcare experiences.

Data Management and Analysis

Analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis, integrated with the Delanerolle and Phiri framework. Researchers first immersed themselves in the data through repeated reading of transcripts and field notes. Initial codes were generated inductively and mapped onto the five framework domains, with particular emphasis on health-system interactions.

Codes were then organised into candidate themes and sub-themes reflecting recurrent experiences of service availability, accessibility, quality, and responsiveness. Themes were refined collaboratively by the research team to ensure they were clear and accurately represented the data. Contextual mapping highlighted how systemic factors influenced women’s experiences across rural and urban settings.

Bilingual analysts cross-checked translations to preserve linguistic accuracy and cultural meaning. Verbatim quotes were carefully selected to illustrate key themes, while idiomatic expressions were discussed with the local team to maintain their integrity. Community validation workshops were held to ensure the findings resonated with participants and stakeholders.

Adherence to COREQ Guidelines

This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline to ensure transparency and methodological rigour in participant recruitment, data collection, analysis, and reporting.

Results

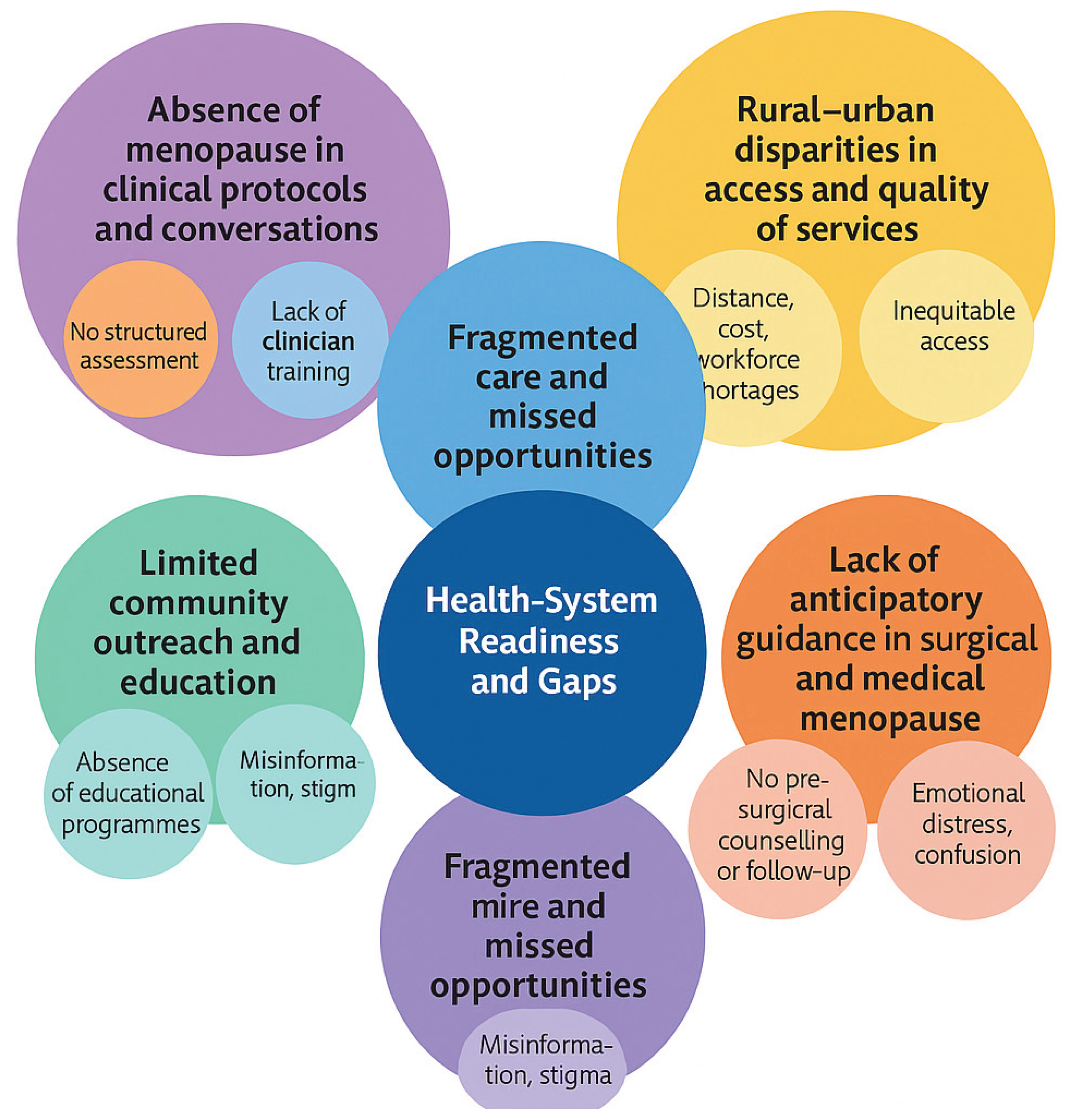

The analysis of 28 interviews revealed how systemic neglect and limited health-system readiness affect women experiencing menopause in Rwanda. Across rural and urban settings, women described the invisibility of menopause within health services, the absence of clear care pathways, inequities between rural and urban populations, and the lack of anticipatory guidance for those undergoing surgical or medical menopause. Five interconnected themes were identified: (1) absence of menopause in clinical protocols and conversations, (2) fragmented care and missed opportunities, (3) rural–urban disparities in access and quality of services, (4) lack of anticipatory guidance in surgical and medical menopause, and (5) limited community outreach and education (

Table 1). These themes illustrate a consistent pattern of unmet needs and systemic gaps across all levels of care (

Figure 1).

Theme 1: Absence of Menopause in Clinical Protocols and Conversations

Women consistently reported that menopause was not routinely discussed during healthcare consultations. Instead, clinical encounters were dominated by monitoring blood pressure, diabetes, and other non-communicable diseases, with menopausal concerns overlooked. This absence reinforced the perception that menopause was not a legitimate health concern requiring professional attention.

A woman from an urban area explained:

“They check my blood pressure but not menopause. No one asks about these changes or how they affect me.” (PID02)

Even women employed within health facilities described a lack of professional awareness and discussion:

“Menopause is not discussed enough, even among us as health workers. It is as if it does not exist.” (PID05)

Others described routine consultations that failed to acknowledge menopause as a health issue:

“They never ask about menopause or ageing problems, only blood pressure and sugar.” (PID27)

“The clinic doesn’t ask about menopause. They just take the pressure and give tablets.” (PID03)

“When I go to the hospital, they treat my other conditions, but menopause is never mentioned.” (PID04)

This lack of engagement meant that symptoms went unrecognised, and women were left to manage them in isolation, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

“We suffer quietly because doctors don’t ask, and we don’t know if it is important to tell them.” (PID07)

The invisibility of menopause in clinical discussions perpetuated misinformation and self-blame, with women attributing their symptoms to ageing or weakness:

“I thought it was just old age; no one explained it was menopause.” (PID26)

“Even when I mentioned my pain, they only said it is because of age, not menopause.” (PID27)

Several participants expressed disappointment that women’s midlife health was not viewed holistically:

“They focus on blood pressure and diabetes, but our other changes are ignored.” (PID02)

“No one counsels us about this time of life, yet it affects everything.” (PID04)

Theme 2: Fragmented Care and Missed Opportunities

Where women did seek care, they encountered fragmented and uncoordinated services. Many reported being referred between different clinics or departments without receiving clear explanations or effective support. Surgical and cancer-related pathways were particularly disjointed, with follow-up focusing solely on surgical recovery or disease progression, rather than the holistic impacts of menopause.

A participant who underwent surgery recalled:

“They didn’t give me much counselling after the operation. The focus was only on my wounds, not about how I was feeling inside.” (PID06)

Women who had undergone hysterectomy or medical procedures reported that their recovery was narrowly defined by physical healing, while psychological distress and vasomotor symptoms were neglected:

“After surgery, they only cared about whether the stitches healed. No one asked why I couldn’t sleep or why I cried.” (PID06)

“Even in the hospital where I work, menopause is not mentioned. The system looks only at diseases, not at women as a whole.” (PID05)

Participants frequently described inconsistent advice and unclear communication between clinicians, leading to a sense of confusion and mistrust:

“One nurse says it’s normal, another says I should take medicine, but no one explains properly what is happening.” (PID03)

“I was sent from one clinic to another and still got no answers.” (PID04)

Several women also highlighted missed opportunities for preventive or supportive counselling, especially in post-surgical and chronic illness contexts:

“After my hysterectomy, no one spoke about menopause or emotions. I only learnt from other women later.” (PID06)

“They measure my blood pressure and sugar, but never talk about menopause or how to live better with it.” (PID27)

Another woman undergoing cancer treatment shared:

“They treat my cancer, but no one asks about the changes in my body or my emotions. It feels like part of me is ignored.”(PID08)

These experiences highlight how opportunities to provide integrated, woman-centred care are consistently missed, resulting in untreated symptoms and heightened psychological distress.

Theme 3: Rural–Urban Disparities in Access and Quality of Services

Rural women described significant barriers to physically accessing care, including long travel distances, poor roads, and unaffordable transport costs. Even when they reached clinics, shortages of trained staff and essential medicines further restricted service availability.

A farmer explained:

“Transport is difficult and medicine is expensive. Sometimes I just stay home and endure the pain.” (PID07)

In contrast, urban women were physically closer to facilities but reported subtler forms of neglect. While they could reach services, the quality of care was often limited, with menopause rarely addressed even in well-resourced settings:

“Being near the hospital does not mean they will help you. They focus on other diseases, not menopause.” (PID05)

This contrast demonstrates that while physical access is a critical barrier in rural areas, service invisibility remains a significant issue in urban contexts.

Theme 4: Lack of Anticipatory Guidance in Surgical and Medical Menopause

Women undergoing hysterectomy or cancer treatment described being unprepared for the sudden and severe onset of menopausal symptoms. None received pre-surgical counselling or clear information about what to expect, leaving them fearful and uncertain. One participant reflected:

“The suddenness after surgery made it worse. The hot flushes and mood swings came without warning.” (PID05)

Another woman explained how this lack of preparation compounded her anxiety:

“I was scared because I didn’t understand what was happening to me. I thought something was wrong with my body.”(PID06)

The absence of anticipatory guidance represents a significant missed opportunity for early intervention and psychological support.

Participants described feeling abandoned immediately after discharge, with medical care focusing solely on surgical wounds or disease management:

“They didn’t give me much counselling after the operation. The focus was only on my wounds, not about how I was feeling inside.” (PID06)

“After the surgery, nobody told me that these emotional and body changes were part of menopause.” (PID05)

Women with cancer diagnoses described a similar absence of anticipatory support, leaving them to interpret menopausal symptoms as a recurrence or worsening of disease:

“They treat my cancer but never explained that these hot flushes and sweating could be from menopause.” (PID08)

“I thought the changes in my body were from the cancer returning, but later I learned it was menopause.” (PID08)

Theme 5: Limited Community Outreach and Education

Community health workers are central to Rwanda’s health system, yet menopause education and outreach are almost entirely absent from their work. Without structured information at community level, women rely on peers, family members, or informal networks for advice. A participant from a rural area shared:

“There is no information in the community. We depend on what other women say, but sometimes it is wrong.” (PID09)

This lack of accurate information perpetuates myths and stigma, reinforcing cultural silence and discouraging help-seeking.

Several women described learning about menopause only through informal discussions rather than organised education or health promotion:

“We hear things from each other, not from the health centres. Everyone just guesses what is happening.” (PID02)

“Even when community health workers visit, they talk about pregnancy or malaria, not menopause.” (PID07)

Others noted that silence within households and communities leaves women unprepared for the transition:

“In my family, no one talked about it, so when it happened, I didn’t know what was normal.” (PID03)

“Older women sometimes give advice, but it’s mixed with myths and fear.” (PID07)

Contextual Analysis

The findings reveal a health system that is ill-prepared to meet the needs of women experiencing menopause. Menopause is invisible at every level of care, from primary services to specialist pathways such as surgery and oncology. While women regularly engage with the health system for other conditions, their menopausal symptoms are rarely acknowledged or addressed, reflecting a systemic failure to prioritise midlife and older women’s health.

Rural women face dual challenges of physical access and service quality. Long travel distances, poor infrastructure, and unaffordable transport create significant barriers to care. Even when they reach clinics, staff shortages and limited resources prevent consistent service delivery. In contrast, urban women benefit from physical proximity but encounter subtler forms of neglect, where menopause remains absent from consultations despite the availability of services.

Cultural expectations of stoicism and silence intersect with these structural barriers, reinforcing women’s isolation and discouraging proactive help-seeking. Without reliable information or community outreach, menopause is framed as a private issue rather than a legitimate health concern. This invisibility has profound consequences for women’s quality of life, mental health, and economic participation. It also limits the health system’s ability to respond to an ageing population where the burden of menopause will continue to grow.

Healthcare System Access Analysis

The Rwandan health system has made significant progress in areas such as maternal health, family planning, and infectious disease control, but menopause remains absent from health planning and service delivery. Participants repeatedly described how healthcare services were geared towards reproductive health and infectious diseases, with little consideration for the needs of midlife and older women. One woman highlighted this systemic gap, saying;

“They focus on children and pregnancy. Once you stop giving birth, it is like you no longer matter to the clinic.” (PID09)

Access to care is shaped by geography, socio-economic status, and the availability of trained health workers. Rural populations face the greatest inequities, with physical access severely constrained by distance, poor roads, and a lack of affordable transport. For many rural women, these barriers lead to delayed care or complete avoidance of health facilities. A farmer described her experience:

“Transport is difficult and medicine is expensive. Sometimes I just stay home and endure the pain.” (PID07)

Financial barriers further limit access, as most women rely on out-of-pocket payments for services and medications. Without affordable options, some women turn to traditional remedies or advice from peers, which can lead to misinformation and untreated symptoms.

“If you cannot afford the hospital, you ask other women. Sometimes what you hear is wrong, but there is no other choice,” explained one rural participant (PID11).

In urban settings, physical access to clinics and hospitals was less problematic, but women encountered a different form of exclusion. Services were often highly specialised and focused on disease-specific programmes such as HIV, maternal health, or chronic disease management. Menopause did not fit within these service models, resulting in systemic neglect.

“Being near the hospital does not mean they will help you. They focus on other diseases, not menopause,” shared an urban participant (PID05)

Another added;

“They check my blood pressure but not menopause. No one asks about these changes or how they affect me.” (PID02)

Community health workers, who play a vital role in Rwanda’s health infrastructure, were described as almost entirely absent from menopause-related care. Their work remains focused on maternal and child health, leaving a gap in outreach and education for midlife and older women. This lack of community-based engagement perpetuates silence and stigma.

“The community health workers come to talk about pregnancy or babies, but they never talk about menopause. We are left to figure it out ourselves,” (PID12)

Women consistently expressed frustration that menopause was excluded from community health agendas and public education campaigns:

“They talk about malaria, pregnancy, and family planning, but not menopause. We are forgotten.” (PID07)

“When health workers come, they check children’s health, but they don’t ask us how we are.” (PID03)

Expanding the remit of community health workers to include midlife health could transform access, particularly for rural women. Education and peer support were highlighted as critical needs, with several women expressing a desire for more accurate information.

“There is no information in the community. We depend on what other women say, but sometimes it is wrong,” said a rural participant (PID09)

“If they can teach about HIV or childbirth, they should also teach us about menopause and ageing.” (PID02)

“Many women believe it’s a curse or punishment because no one explains it properly.” (PID27)

These findings underscore that without targeted policies and investment, the health system will continue to overlook menopause, leaving a growing segment of the population unsupported. A participant summarised this systemic neglect, stating;

“When you are young, they care for you. When you are older, you are on your own.” (PID06)

To address these gaps, a responsive approach must integrate menopause into national health strategies and routine care. Clinicians require training to recognise and manage menopausal symptoms, while health facilities must provide equitable access to essential medicines and counselling. By prioritising education, outreach, and service development, Rwanda can create a health system that supports women throughout the life course, reducing stigma and promoting equity for midlife and older women.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a significant gap in Rwanda’s health system regarding the recognition and management of menopause. Women’s narratives highlighted that menopause remains invisible within healthcare services, leaving those experiencing both natural and surgically or medically induced menopause unsupported. While natural menopause was often endured in silence, women facing abrupt transitions due to hysterectomy or cancer treatment experienced distress and confusion, compounded by the absence of anticipatory counselling and follow-up care. Across rural and urban settings, cultural expectations of stoicism intersected with systemic neglect, leading to delayed diagnosis, unmanaged symptoms, and reliance on informal or traditional care networks. These experiences reflect a broader pattern in which women’s health beyond reproductive years is deprioritised, reinforcing the invisibility of midlife and older women within health planning and service delivery.

Healthcare System Implications

These findings have critical implications for healthcare provision. Rural women face profound structural barriers, including long distances to facilities, unaffordable transport, and staff shortages, resulting in limited access to care [

13,

14,

15]. Even when services are physically accessible, the content and quality of care remain inadequate, with clinics and hospitals focused on maternal health, infectious disease, and chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, rather than holistic women’s health. The absence of dedicated menopause services or protocols leads to fragmented, disease-specific care. Training gaps among healthcare workers further perpetuate this neglect, with clinicians unprepared to address menopause or provide appropriate counselling. Community health workers, who are essential to Rwanda’s health infrastructure, are not engaged in outreach or education for midlife health, leaving women without reliable information or preventive support. Addressing these systemic issues requires a shift towards integrated, life-course approaches to women’s health that recognise menopause as a vital stage requiring attention and resources.

Policy Impact

The invisibility of menopause within national health policies contributes to its neglect at service level [

23,

24]. Current reproductive health strategies in Rwanda focus on maternal health and family planning, with no systematic inclusion of midlife and ageing women’s health needs. The study findings highlight an urgent need for policy reform to bridge this gap. This includes integrating menopause into national health plans, ensuring financial protection for essential medications, expanding the role of community health workers, and improving surveillance systems to track prevalence and outcomes. Strengthening health financing and infrastructure is essential to reduce inequities between rural and urban populations and ensure equitable access to care. Below are few recommendations.

| Area |

Recommendation |

Implementation Level |

| Clinical care |

Introduce standardised menopause screening in primary care, surgical, and oncology services. |

National and district health services |

| |

Train clinicians and nurses on menopause management and holistic women’s health. |

Ministry of Health, medical councils |

| Community outreach |

Expand community health workers’ remit to include menopause education and support. |

Local health structures, NGOs |

| |

Develop culturally sensitive campaigns to reduce stigma and promote awareness. |

National public health campaigns |

| Health system access |

Provide transport vouchers and outreach clinics to reduce rural access barriers. |

Government health financing schemes |

| |

Ensure affordable and continuous supply of essential menopause-related medicines. |

National pharmacy and insurance systems |

| Policy reform |

Integrate menopause into reproductive and ageing health policies. |

National health strategy and policy |

| |

Establish surveillance systems to collect menopause data for planning and monitoring. |

Ministry of Health, statistical agencies |

Conclusion

This study highlights the systemic invisibility of menopause in Rwanda and its profound effects on women’s health and wellbeing. Menopause is neither routinely assessed nor supported within healthcare services, leaving women to manage symptoms alone or through informal networks. Rural–urban disparities further compound inequities, with rural women facing barriers of access and urban women experiencing neglect despite physical proximity to services. Addressing these challenges requires investment in education, training, and infrastructure to create an integrated, responsive health system. By recognising menopause as a public health priority, Rwanda can improve quality of life and ensure equitable care for midlife and older women.

Author Contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. DCI submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study in Ghana. DCI and team recruited participants to the study. GD and JQS conducted the data analysis. GD and DCI wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors DCI, GJP, KC,NHC, SMI, JDH, KJMV,

Data Availability Statement

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable. DU, MM, AK, ET, EH, JS, VP, JT, LS, SH, KP, KE, CA, VT, GUE, OK,NR, TM, JD, LA, NA, BM,IM, FT,NM, THT,PKM,MI,RK,CLB,HFK, RP, JS,NP,SE,PP,GD critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Rwanda (CMHS-UR Institutional Review Board: No. 207/CMHS IRB/2025).

Consent to Participate

Participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Consent for Publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Donatella Fontana, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumde, Heitor Cavalini, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Chukwuemeka Chidindu Njoku, Ayyuba RABIU, Chijioke Chimbo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuaz, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Susan Nweje, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Michael Nnaa Otis, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Kim-Yen Lee, Siti Nurul Aiman Ali Madinah, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Xiu-Sing Wong, John Yen-Sing Lee, Yee-Theng Lau, Alyani Mohamad Mohsin, Nor Fareshah Mohd Nasir, Diana Suk-Chin Lau, Farhawa Zamri, Artini Abidin, Aini Hanan Azmi, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Fatin Imtithal Adnan, Puong Rui-Lau, Xin-Sheng Wong, Geok-Seim Lim, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Karen Kristelle, Asma’ Mohd Haslan, Noorhazliza Abdul Patah, Vaitheswariy Rao Nalathambi, Juhaida Jaafar, Jinn-Yinn Phang, Lee Leong Wong, Nurfauzani Ibrahim, Siew-Yew Ting, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Norhazura Hamdan, Min-Huang Ngu, Choon-Moy Ho, Safilah Dahian, Daniel Leong-Hoe Ngu, Sing-Yee Khoo, Kamilah Dahian, Jeffrey Soon-Yit Lee, Shubashini Kanagaratnam, Amirah Fazira Zulkifli, Manisha Mathur, Rukshini Puvanendran, Farah Safdar, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Raksha Aiyappan, Ganesh Dangal, Puja Lam, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Prasanna Herath, Damayanthi Dassnayake, Chandrani Herath, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Cristina Laguna Benetti-Pinto, Renan Massao Nakamura, Daniela Angerame Yela, Gabriela Pravatta Rezende, Renan Massao Nakamura, Isaac Lartey Narh, Kwasi Eba-Polley, Catherine Narh Menka, Prince Osei, Nana Osei, Lemuel Lartey, Bernard Bortieh, Cletus Kumi, Elijah Boafo, Janet Ayorkor Anyetei, Edel Issabella Arthur, Horatio King Glover, Fredrick Amoah, Ethel Larteley Boye, Zerish Lamptey, Laurinda Gyan, Bharat Prasad, Shaziya Noor, Kumari Shilpa, Poonam Singh, Usha Jha, Manu Chatterjee, Oscar Mahinyila, Alosisia Shemdoe, Kornelio Mpangala, Filbert Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Mpoki Kaminyoge, Thomas Alon

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Delanerolle, G. et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 13, e196-e198 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Thurston, R. C., Thomas, H. N., Castle, A. J. & Gibson, C. J. Menopause as a biological and psychological transition. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1-14 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Comparetto, C. & Borruto, F. Vol. 7 1-47 (LIDSEN Publishing Inc, 2023).

- Utian, W. H. Psychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive review. Health and Quality of Life outcomes 3, 47 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Brewis, J., Beck, V., Davies, A. & Matheson, J. The effects of menopause transition on women’s economic participation in the UK. (2017).

- D’Angelo, S. et al. Impact of menopausal symptoms on work: findings from women in the Health and Employment after Fifty (HEAF) Study. International journal of environmental research and public health 20, 295 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Matina, S. S., Cohen, E., Mokwena, K. & Mendenhall, E. Menopause and aging in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Climacteric, 1-12 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Sitini, B. et al. Prevalence, impact and management of postmenopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women in Rwanda. Climacteric 26, 613-618 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rudasingwa, M., Jahn, A., Uwitonze, A.-M. & Hennig, L. Increasing health system synergies in low-income settings: Lessons learned from a qualitative case study of Rwanda. Global Public Health 17, 3303-3321 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P., Sapsford, R. & Binagwaho, A. Learning from success: how Rwanda achieved the millennium development goals for health. World development 92, 103-116 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Adler, A. et al. What women want: A mixed-methods study of women’s health priorities, preferences, and experiences in care in three Rwandan rural districts. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 162, 525-531 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Drobac, P., Basilico, M., Messac, L., Walton, D. & Farmer, P. Building an effective rural health delivery model in Haiti and Rwanda. Reimagining global health: An introduction 26, 133 (2013).

- Tengera, O. et al. Barriers hindering attendance and adherence to antenatal care visits among women in rural areas in Rwanda: An exploratory qualitative study. PLoS One 20, e0323762 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Selden, O., Rusingiza, E. & Balkrishnan, R. Overview, Infrastructural Challenges, Barriers to Access, and Progress for Rwanda’s Healthcare System: A Review. Integrative Journal of Medical Sciences 12 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Nzasabimana, P. et al. Barriers to equitable access to quality trauma care in Rwanda: a qualitative study. BMJ open 13, e075117 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tuyisenge, G., Crooks, V. A. & Berry, N. S. Using an ethics of care lens to understand the place of community health workers in Rwanda’s maternal healthcare system. Social Science & Medicine 264, 113297 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Tuyisenge, G., Crooks, V. A. & Berry, N. S. Facilitating equitable community-level access to maternal health services: exploring the experiences of Rwanda’s community health workers. International journal for equity in health 18, 181 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Condo, J. et al. Rwanda’s evolving community health worker system: a qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Human resources for health 12, 71 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Islam, R. M. et al. Menopause in low and middle-income countries: a scoping review of knowledge, symptoms and management. Climacteric, 1-38 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Logie, D. E., Rowson, M. & Ndagije, F. Innovations in Rwanda’s health system: looking to the future. The Lancet 372, 256-261 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Binagwaho, A. et al. Rwanda 20 years on: investing in life. The Lancet 384, 371-375 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women’s Health Research. (2025).

- Martin-Key, N. A., Funnell, E. L., Spadaro, B. & Bahn, S. Perceptions of healthcare provision throughout the menopause in the UK: a mixed-methods study. npj Women’s Health 1, 2 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Laker, B. & Rowson, T. Making the invisible visible: why menopause is a workplace issue we can’t ignore. BMJ leader (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).