Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Rationale

Methods

Study Design

Research Team and Reflexivity

Participant Selection and Recruitment

Setting and Data Collection

Translation and Transcription

Data Analysis

Trustworthiness and Rigour

- Credibility: Triangulation across researchers and iterative coding discussions.

- Dependability: Maintenance of an audit trail including coding decisions, codebook (Table 1) evolution, and reflexivity logs.

- Confirmability: Peer debriefing within the research team to minimise individual bias.

- Transferability: Detailed description of participants, settings, and contexts to enable applicability to other health systems.

Ethical Considerations

Results

Thematic Analysis

Symptom Burden is Multidimensional and Mutually Reinforcing

Psychological Impacts Pivot Around Irritability, Anxiety, and Lowered Mood

Coping is Diverse: from Faith and Self-Care to Pharmacology and HRT Constrained by Access and Risk

Care Pathways Bifurcate by Ability to Pay; Communication Quality is a Decisive Determinant of Outcomes

Inequities are Structural, not Incidental

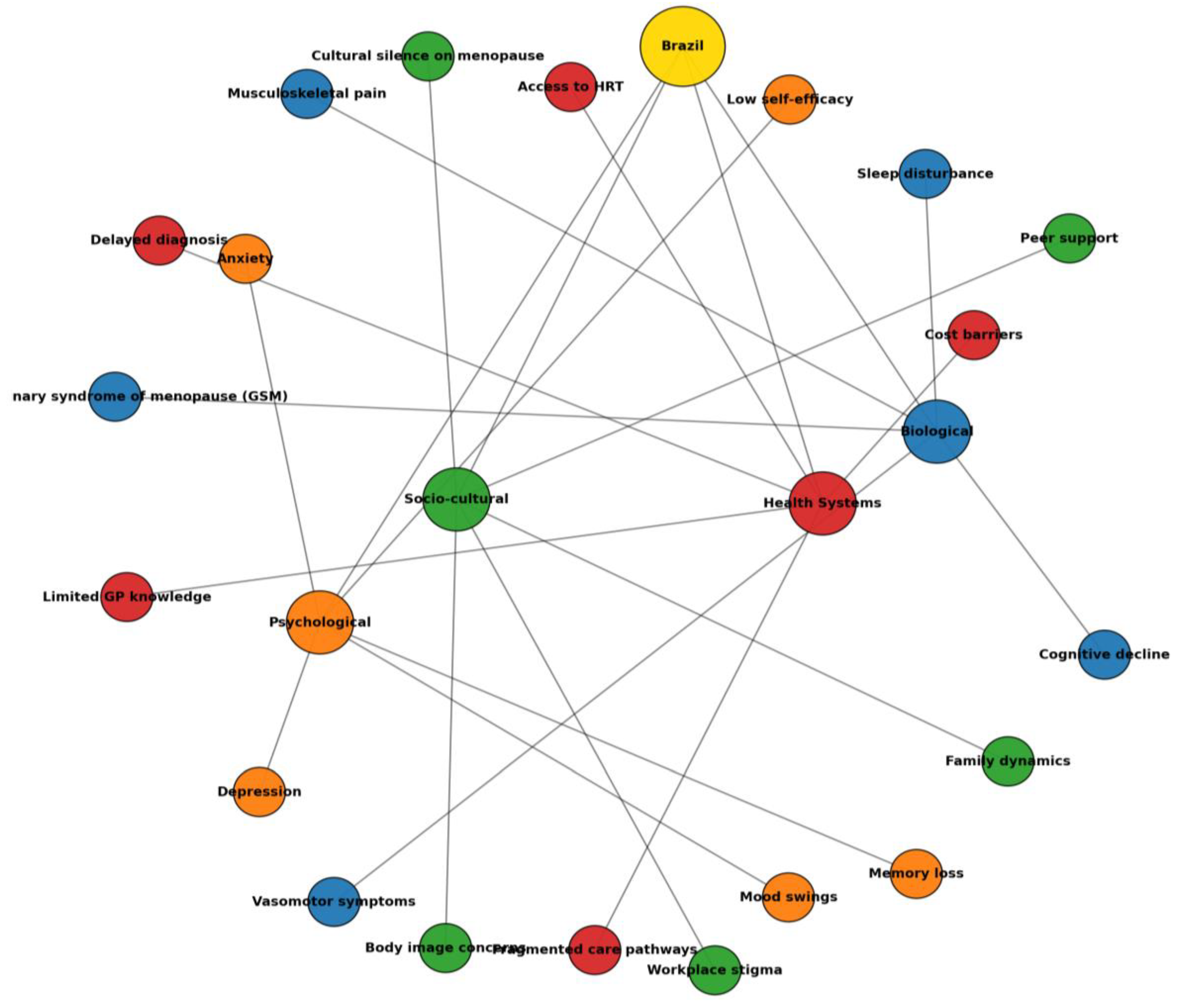

Contextual Analysis

Colloquial Terms Table (English- Portuguese, as Used by Participants)

| English | Portuguese (colloquial) |

| Hot flush / heat wave | Calorão / onda de calor |

| Night sweats | Suor noturno |

| Vaginal dryness | Secura (na vagina) / ressecamento |

| Burning (vaginal) | Ardência |

| Painful sex | Dor na relação / doía para ter relação |

| No libido | Libido zero / sem vontade |

| Short fuse / easily irritated | Pavio curto |

| Angry at anything | Ficar brava por qualquer coisa |

| Brain fog / slow thinking | Cabeça lenta |

| Forgetful | Memória falha / esquecida |

| Tiredness / fatigue | Canseira / cansaço |

| Feeling old | Me sentindo velha / envelhecendo rápido |

| Hellish experience | Inferno |

| Primary care clinic | Postinho / UBS |

| Public system | SUS |

| Private insurance | Convênio |

| Reception/front-desk | Recepção |

| Compounded cream | Remédio manipulado |

| Testosterone gel | Gel de testosterona |

| Combined pill (brand) | Ceci |

| HRT patch/gel | Adesivo/gel de hormônio |

Discussion

Population Science

Clinical Implications

| Domain | Policy Recommendations |

| Health system strengthening | • Integrate menopause into Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) through standardised screening, counselling, and management protocols.• Establish multidisciplinary menopause clinics in specialized public care centers and leverage the Family Health Strategy for community support. |

| Equitable access to treatment | • Guarantee the availability of affordable hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and non-hormonal alternatives through SUS, reducing urban–rural and public–private disparities.• Implement bulk procurement and subsidy mechanisms to ensure cost-effectiveness and sustainability. |

| Clinical training and education | • Introduce mandatory menopause education in medical and nursing curricula, with ongoing continuing professional development for general practitioners and gynaecologists.• Equip community health workers with training to deliver basic counselling, early recognition, and referral. |

| Public health communication | • Launch culturally tailored campaigns to reduce stigma and normalise open discussion of menopause.• Use different tools, including non-digital ones when necessary to facilitate accessibility. |

| Workplace and societal policy | • Promote workplace protections through national labour regulations, ensuring flexibility, reasonable adjustments, and anti-discrimination safeguards.• Incorporate menopause into gender equity and aging strategies to align with Brazil’s commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals, facilitating a more prolonged incorporation of women into the labor market |

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Thurston, R. C., Thomas, H. N., Castle, A. J. & Gibson, C. J. Menopause as a biological and psychological transition. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1-14 (2025).

- Costa, C. R. N. d., Costa, N. C. V. & Manica, D. T. Menstruation as a research topic in the humanities in Brazil: a state of the art. Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society 7, 2424097 (2024).

- Delanerolle, G. et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 13, e196-e198 (2025).

- Lay, A. A. R., do Nascimento, C. F., de Oliveira Duarte, Y. A. & Chiavegatto Filho, A. D. P. Age at natural menopause and mortality: a survival analysis of elderly residents of São Paulo, Brazil. Maturitas 117, 29-33 (2018).

- Lay, A. A. R., de Oliveira Duarte, Y. A. & Chiavegatto Filho, A. D. P. Factors associated with age at natural menopause among elderly women in São Paulo, Brazil. Menopause 26, 211-216 (2019).

- Ygnatios, N. T. M. et al. Age at natural menopause and its associated characteristics among Brazilian women: cross-sectional results from ELSI-Brazil. Menopause 31, 693-701 (2024).

- Pompei, L. M. et al. Profile of Brazilian climacteric women: results from the Brazilian Menopause Study. Climacteric 25, 523-529 (2022).

- Afonso, L. O. et al. Prevalence of hysterectomy and associated factors in Brazilian women aged 50 and older: findings from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSI-Brazil). BMC Public Health 24, 1747 (2024).

- Bagga, S. S., Tayade, S., Lohiya, N., Tyagi, A. & Chauhan, A. Menopause dynamics: From symptoms to quality of life, unraveling the complexities of the hormonal shift. Multidisciplinary Reviews 8, 2025057-2025057 (2025).

- Carvalho, A. O. d., Andrade, L. B. d., Ruano, F. F. L., Wigg, C. M. D. & Marinheiro, L. P. F. Knowledge, practices and barriers to access sexual health of women in the menopausal stages: a cross-sectional study with Brazilian gynecologists. BMC Women’s Health 24, 52 (2024).

- Da Silva, A. R. & Tanaka, A. C. d. A. Factors associated with menopausal symptom severity in middle-aged Brazilian women from the Brazilian Western Amazon. Maturitas 76, 64-69 (2013).

- Bilal, U. et al. Inequalities in life expectancy in six large Latin American cities from the SALURBAL study: an ecological analysis. The lancet planetary health 3, e503-e510 (2019).

- Tserotas, K. & Blumel, J. E. REDLINC: two decades of collaborative insights into menopause and women’s health in Latin America. Climacteric, 1-10 (2025).

- Connelly, R., DeGraff, D. S. & Levison, D. Women’s employment and child care in Brazil. Economic development and cultural change 44, 619-656 (1996).

- Bahiyah Abdullah, M., Moize, B., Ismail, B. A. & Zamri, M. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms, its effect to quality of life among Malaysian women and their treatment seeking behaviour. Med J Malaysia 72, 95 (2017).

- Manoharan, A. et al. Health-seeking behaviors and treatments received for menopause symptoms: a questionnaire survey among midlife women attending primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia. Journal of Menopausal Medicine 29, 119 (2023).

- Laker, B. & Rowson, T. Making the invisible visible: why menopause is a workplace issue we can’t ignore. BMJ leader (2024).

- Li, Q., Gu, J., Huang, J., Zhao, P. & Luo, C. “ They see me as mentally ill”: the stigmatization experiences of Chinese menopausal women in the family. BMC Women’s Health 23, 185 (2023).

- Pinto Neto, A. M. et al. Caracterização das usuárias de terapia de reposição hormonal do Município de Campinas, São Paulo. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 18, 121-127 (2002).

- de Arruda Amaral, I. C. et al. Factors associated with knowledge about menopause and hormone therapy in middle-aged Brazilian women: a population-based household survey. Menopause 25, 803-810 (2018).

- Augusto, R. M., Oliveira, D. C. d. & Polidoro, M. Description of drugs prescribed for hormone therapy in specialized health services for transsexual and transvestite persons in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2020. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 31, e2021502 (2022).

- Ferreira-Campos, L. et al. Hormone therapy and hypertension in postmenopausal women: results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 118, 905-913 (2022).

- Panay, N. et al. Menopause and MHT in 2024: addressing the key controversies–an International Menopause Society White Paper. South African General Practitioner 5, 119-134 (2024).

- Faubion, S. S. et al. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 29, 767-794 (2022).

- Low, T. L., Cheong, A. T., Devaraj, N. K. & Ismail, R. Prevalence of offering menopause hormone therapy among primary care doctors and its associated factors: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 19, e0310994 (2024).

- Macinko, J. & Harris, M. J. Brazil’s family health strategy—delivering community-based primary care in a universal health system. New England Journal of Medicine 372, 2177-2181 (2015).

| Code | Definition | Determinant(s) | Example Quote (PID) | Theme |

| Hot flushes / calorão | Sudden intense heat, often with sweating | Hormonal decline | “The hot flushes… my God! Horrible.” (PID7) | Symptom burden – vasomotor |

| Night sweats | Nocturnal sweating disrupting sleep | Vasomotor instability | “I woke up drenched, bed wet.”(PID4) | Symptom burden – vasomotor |

| Insomnia | Difficulty initiating/maintaining sleep | Vasomotor symptoms, anxiety | “I couldn’t sleep… I rolled in bed.”(PID16) | Symptom burden – sleep |

| Fragmented sleep | Multiple awakenings, unrefreshing sleep | Anxiety, night sweats | “I woke up and couldn’t sleep again.” (PID20) | Symptom burden – sleep |

| Vaginal dryness / secura | Reduced lubrication, painful sex | Oestrogen decline, hysterectomy | “Dryness in the vagina, pain in sex, libido zero.” (PID20) | Symptom burden – GSM |

| Painful sex / dor na relação | Dyspareunia linked to dryness | GSM | “Very dry… pain during sex.”(PID18) | Symptom burden – GSM |

| Recurrent UTIs | Frequent urinary infections | Oestrogen deficiency, GSM | “I get infections almost every month.” (PID8) | Symptom burden – GSM |

| Libido loss / libido zero | Diminished sexual desire | GSM, mood changes | “No desire for sex, libido gone.”(PID7, PID5) | Symptom burden – GSM |

| Memory lapses | Forgetting tasks, poor recall | Menopause, sleep loss | “I forgot many things.” (PID11) | Symptom burden – cognitive |

| Concentration difficulties | Reduced focus, task repetition | Fatigue, insomnia | “I had to redo tasks 3–4 times.”(PID20) | Symptom burden – cognitive |

| Brain fog / cabeça lenta | Slowed mental processing | Sleep loss, hormonal changes | “It seemed like my head was slow.”(PID4) | Symptom burden – cognitive |

| Back pain | Chronic lumbar pain | Osteoporosis, disability | “My back always hurts.” (PID3) | Symptom burden – musculoskeletal |

| Joint pain / knee/spine issues | Musculoskeletal complaints | Chronic illness | “Many spine problems, knee surgery.” (PID2) | Symptom burden – musculoskeletal |

| Weight gain | Noticeable post-menopause weight increase | Hormonal, lifestyle | “I gained a lot of weight after menopause.” (PID1) | Symptom burden – body image |

| Attributional ambiguity | Difficulty separating menopause from comorbidities | Disability, surgery | “I don’t know if it’s menopause or the amputation.” (PID1) | Symptom burden |

| Irritability / pavio curto | Short temper, easy frustration | Hormonal, sleep loss | “Short-fused… everything irritates me.” (PID12) | Psychological impact |

| Anxiety / nervosismo | Heightened worry, nervousness | Pre-existing or menopause-triggered | “I didn’t know I was so anxious until menopause.” (PID2) | Psychological impact |

| Low mood / sadness | Emotional downturn, crying, demotivation | Hormonal, occupational stress | “I became more sad, cried easily.”(PID15) | Psychological impact |

| Accelerated ageing | Feeling older, diminished identity | Cultural scripts | “I felt I was ageing fast.” (PID18) | Psychological impact |

| Faith-based coping | Reliance on prayer, Bible | Religious orientation | “I read the Bible and prayed a lot.”(PID5) | Coping |

| Self-care routines | Exercise, meditation, therapy apps | Individual agency | “I used meditation apps.” (PID3) | Coping |

| Psychotropic use | Antidepressants/anxiolytics | Anxiety, depression, pain | “I take fluoxetine.” (PID20); “Duloxetine for anxiety and pain.”(PID2) | Coping |

| HRT use | Hormone replacement therapy (gel, patch, tablet) | Private access, physician | “I use oestrogel and Duphaston.”(PID20) | Coping |

| HRT contraindication | Unable to use HRT | Thrombosis, risk factors | “I couldn’t use hormones because of thrombosis.” (PID1) | Coping |

| Clinician reluctance | Doctors avoid prescribing | Fear of side effects | “Doctors are afraid to prescribe.”(PID13) | Healthcare |

| Complementary therapies | Acupuncture, reiki, homeopathy | Cultural adaptation | “I tried acupuncture and reiki.”(PID2) | Coping |

| Private care reliance | Access via insurance/self-pay | Socioeconomic privilege | “I do everything private.” (PID20) | Healthcare access |

| SUS reliance | Dependence on public system | Socioeconomic constraint | “I do everything through SUS.”(PID1) | Healthcare access |

| Appointment delays | Long waits, quick consults | Under-resourcing | “It takes long to schedule, consults are quick.” (PID14) | Healthcare access |

| Doctor turnover | Lack of continuity | Workforce instability | “Hard to trust; depends on who you get.” (PID17) | Healthcare access |

| Post-surgical counselling gaps | No menopause briefing post-hysterectomy | Peri-operative care | “I lacked info when I had my uterus removed.” (PID8) | Healthcare access |

| Front-desk gatekeeping | Receptionist/nurse ignorance | System literacy gap | “Receptionist asked odd questions about hormones.” (PID18) | Healthcare access |

| Misinformation online | Confusion from internet | Information desert | “On the internet it’s worse… everyone says different.” (PID13) | Healthcare access |

| Education demand | Desire for group sessions/resources | Community-based support | “Why not a group for menopause?”(PID13) | Healthcare access |

| Equity/ability to pay | Paying vs relying on SUS determines care | Structural inequity | “If you don’t have money, it’s complicated.” (PID9) | Systemic inequity |

| Cultural silence | Generational non-discussion | Social norms | “In my mother’s time nobody spoke.” (PID8) | Systemic inequity |

| Occupational impact | Errors, fatigue, presenteeism | Sleep/cognition loop | “I had to redo tasks 3–4 times.”(PID20) | Systemic inequity |

| Theme | Sub-theme | Determinants | Exposures (what happened) | Example quote (PID) |

| Symptom burden | Vasomotor intensity & cyclicity | Oestrogen decline | Hot flushes, night sweats, daytime sweating cycles | “The hot flushes… my God! Horrible.” (PID7) |

| Sleep fragmentation & non-restorative sleep | Vasomotor activation; anxiety | Difficulty initiating sleep, multiple awakenings, unrefreshing sleep | “I couldn’t sleep… I rolled in bed.” (PID16) | |

| Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) | Oestrogen depletion; surgical menopause | Vaginal dryness, burning, dyspareunia, urinary discomfort/UTIs | “Very dry… pain during sex.” (PID18); “Frequent infections, almost every month.” (PID8) | |

| Sexual function & desire | GSM; mood; relationship context | Low libido, avoidance of sex, partner misunderstanding | “Libido zero.” (PID20); “My ex-husband didn’t understand.” (PID5) | |

| Cognitive efficiency | Menopausal transition; sleep loss | Forgetfulness; slowed processing; reduced concentration; task repetition | “I had to redo tasks 3–4 times.” (PID20); “I forgot many things.” (PID11) | |

| Musculoskeletal pain & fatigue | Osteoporosis; disability; comorbid pain | Back pain; joint pain; daytime fatigue | “My back always hurts.”(PID3) | |

| Weight & body image | Hormonal milieu; mood; activity | Weight gain; altered self-image | “I gained a lot of weight after menopause.” (PID1) | |

| Attributional ambiguity | Multimorbidity; surgical history | Difficulty separating effects of disability/surgery vs menopause | “I don’t know if it’s menopause or the amputation.” (PID1) | |

| Psychological impacts | Irritability & “short fuse” | Hormonal shifts; poor sleep | Lower tolerance, proneness to anger | “Short-fused… everything irritates me.” (PID12) |

| Anxiety amplification | Pre-existing anxiety; transition stressors | Persistent nervousness, hyper-arousal | “I didn’t know I was so anxious until menopause.”(PID2) | |

| Low mood & demotivation | Chronic symptoms; role strain | Sadness, crying, loss of drive | “I became more sad, cried easily.” (PID15) | |

| Identity/ageing sense-making | Social narratives of ageing | Feeling “old”, accelerated ageing | “I felt I was ageing fast.”(PID18) | |

| Coping & management | Faith-based coping | Religious orientation; community | Prayer, Bible reading, meaning-making | “I read the Bible and prayed a lot.” (PID5) |

| Self-care routines | Individual agency; digital access | Exercise, meditation, therapy apps; vitamins | “I used meditation apps and therapy.” (PID3) | |

| Psychotropics | Access; comorbidity | Antidepressants/anxiolytics for mood, sleep, pain | “I take fluoxetine.” (PID20); “Duloxetine for anxiety and pain.” (PID2) | |

| HRT access & effects | Private vs SUS; safety perceptions | Patches/gels/tablets; vaginal oestrogens; symptom relief | “Oestrogel and Duphaston helped.” (PID20) | |

| HRT constraints/contraindications | Thrombosis history; risk perceptions | Non-use despite need; under-prescribing | “I couldn’t use hormones because of thrombosis.”(PID1); “Doctors are afraid to prescribe.” (PID13) | |

| Complementary therapies | Cultural acceptability | Acupuncture, homeopathy, reiki | “I tried acupuncture and reiki.” (PID2) | |

| Workplace self-adaptation | Role autonomy; support | Task pacing, error checking, breaks | “I had to redo tasks several times.” (PID20) | |

| Healthcare access & communication | Private care reliance | Socioeconomic privilege | Direct gynaecology access; steady HRT | “I do everything private.”(PID20) |

| SUS reliance (UBS) pathways | Socioeconomic constraint | Family doctor triage; variable follow-up | “I do everything through SUS.” (PID1) | |

| Appointment logistics & time | Under-resourcing | Delays, rushed consults, scheduling difficulty | “It takes long to schedule… consults are quick.” (PID14) | |

| Continuity/turnover (“doctor shopping”) | Staffing; contracts | Repeating history, inconsistent advice | “It’s hard to trust; depends on who you get.” (PID17) | |

| Post-surgical counselling gaps | Peri-operative education | Hysterectomy without menopause briefing | “I lacked info when I had my uterus removed.” (PID8) | |

| Gatekeeping & staff literacy | Non-clinical staff; stigma | Receptionist/nurse questioning, embarrassment | “Receptionist asked odd questions about hormones.”(PID18) | |

| Misinformation & info deserts | Internet noise; absent materials | Conflicting guidance; fear of hormones | “On the internet it’s worse… everyone says different.”(PID13) | |

| Demand for education & groups | Community models | Desire for group classes/resources | “Why not a group for menopause?” (PID13) | |

| Systemic inequities | Ability to pay = quality of care | Income; insurance | Private/HRT vs public/limited options | “If you don’t have money, it’s complicated.” (PID9) |

| Cultural silence & stigma | Norms; generational gaps | Menopause invisible in families/work | “In my mother’s time nobody spoke.” (PID8) | |

| Occupational consequences | Sleep/cognition; supports | Errors, fatigue, presenteeism | “I had to redo tasks 3–4 times.” (PID20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).