Evidence Before This Study

Previous UK research has largely quantified disparities such as lower HRT prescribing for Black African and Chinese women and postcode-based inequities without delving deeply into lived experiences. Mixed-method surveys have highlighted dismissive clinical attitudes and poor symptom attribution in quantitative summaries but provided limited lived-context insight. Systematic reviews of qualitative studies have broadly described biopsychosocial themes but lacked intersectional depth, particularly for minoritised, trans, surgical, and rural populations.

Added Value of This Study

Our study delivers rich qualitative evidence from 50 diverse participants including cis-women, trans-women, those with surgical and medical menopause and ethnically minoritised women revealing how structural, clinical, and identity-based barriers actually play out in lives. It uniquely uncovers how disparities deepen emotional distress and misdiagnosis intersects with mental health stigma. These lived narratives illuminate unseen layers of inequity that are not accessible through quantitative or less intersectional qualitative methods.

Implications of All the Available Evidence

Together with prior studies, our findings make a compelling case for qualitative voices to shape menopause care policy and practice reforms. They highlight the need for equity-driven, culturally responsive service redesign including clinically integrated menopause hubs, standardised formulary rollout, and inclusive workplace policies. Acting on these insights can transform menopause services to better reflect the lived realities of all UK individuals, not just those captured in numerical data.

Background

Each year, approximately 13 million individuals in the United Kingdom (UK) around one-third of the female population experience perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause, whether due to natural hormonal changes or precipitated by medical or surgical interventions [

1]. Menopause is typically defined by 12 consecutive months without menstruation, but in approximately 1% of women, it occurs prematurely (under age 40) and is even more abrupt and symptomatically intense when medically or surgically induced [

2,

3,

4,

5]. These accelerated menopausal trajectories carry distinct long-term health risks, including elevated risk of depression requiring hospitalization and increased vulnerability to dementia and cardiovascular disease [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Perimenopause commonly beginning in the early to mid-40s is often the most symptomatic phase, characterised by hormonal fluctuations leading to irregular menstrual cycles, hot flushes, mood disturbances, insomnia, and cognitive impairments [

10]. These symptoms are widespread, affecting up to 75% of menopausal people, with around 25% experiencing severe effects that can persist for several years into post-menopause [

11,

12].

The broader societal and economic toll is significant: over 60% of menopausal women report negative impacts on their work, leading to 14 million lost workdays annually and estimated productivity losses of £1.8 billion, with nearly 900,000 women leaving employment due to menopausal symptoms [

13,

14]. Although national policies such as the Women’s Health Strategy, workplace pledges, and employer initiatives have started addressing menopause-related needs, much of this guidance still assumes a cisgender, heterosexual norm and fails to reflect the full diversity of experiences [

15].

Emerging qualitative studies challenge this narrow framing, where cis-women and transgender people experience disproportionate anxiety, poor healthcare access, and structural assumptions that fail to acknowledge their identities [

16]. Furthermore, transgender and non-binary individuals with ovaries or those who experience prostate transitions describe widespread invisibility in healthcare settings that rely on binary language, lack pronoun awareness, and rarely incorporate gender-affirming hormone care alongside menopause management [

17,

18].

Rationale

Persistent disparities in menopause care signal the urgent need for inclusive research methodologies that go beyond quantification. While large-scale surveys provide estimates of symptom burden or economic costs, they lack the interpretive nuance necessary to explain why services systematically fail marginalised populations. Qualitative methods are essential to uncover how stigma, structural inequities, and clinical assumptions shape access, diagnosis, and lived experience. In response, we developed the MARIE study a mixed-methods investigation whose UK Work Package 2 qualitatively explores menopause care across diverse gender, racial, and sexual identities. This arm of the study seeks to amplify voices typically excluded from mainstream evidence by examining the experiences of cisgender women, sexual minority groups, and trans and gender-diverse individuals undergoing perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause, whether naturally occurring or medically induced. Our goal is to generate actionable insights into the barriers and enablers of equitable menopause care, informing national policy, workforce training, and service design in a rapidly diversifying UK.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This qualitative study (WP2a of the MARIE UK project) was conducted as a follow-up to a larger quantitative study on menopause in the UK. We used a cross-sectional, descriptive design involving semi-structured interviews to explore participants’ healthcare experiences. Participants of legal consenting age ≥18 years who had experienced perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause, naturally, medically or surgically were eligible to take part in the study. Cis women, trans gender and LGBTQ+ populations were eligible to take part. A total of 50 participants were purposefully recruited from those who had completed the earlier quantitative phase and consented to be contacted for an interview.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted approximately 60 days after enrolment in the quantitative study at a two-month follow-up. Each participant took part in a one-to-one interview carried out by a trained researcher, either via telephone or videoconference according to participant preference to facilitate UK-wide inclusion. We developed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions and prompts focusing on participants’ experiences of accessing healthcare services for menopausal symptoms, the quality and inclusivity of care received, perceived barriers or facilitators in seeking help, and any unmet needs or suggestions for improvement. Interviews lasted approximately 40–60 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded with permission and transcribed verbatim. Identifiable information was removed to ensure confidentiality, and each participant was assigned a pseudonym or code in the transcripts.

Data Analysis

We employed reflexive thematic analysis to interpret the qualitative data. The analysis followed the established stages of a context and thematic analysis, which involved familiarisation with the transcripts, inductively coding significant features of the data, and iteratively clustering codes into potential themes and sub-themes. Four researchers (SH, KP, KE and DF) independently reviewed and cleaned the transcripts. These researchers then discussed and refined the coding framework, resolved any discrepancies. The data was re-reviewed using an iterative process to develop a thematic schema capturing key aspects of participants’ perimenopausal, menopausal and post-menopausal experiences. Participants quotes were selected to illustrate each theme in the results. We compared themes across different participant sub-groups to identify divergent experiences indicative of health inequalities.

Ethics

The study received integrated ethical and governance approval from the Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales (Reference: 22/EE/0158) and sponsorship from Hampshire and Isle of Wight Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (formally Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

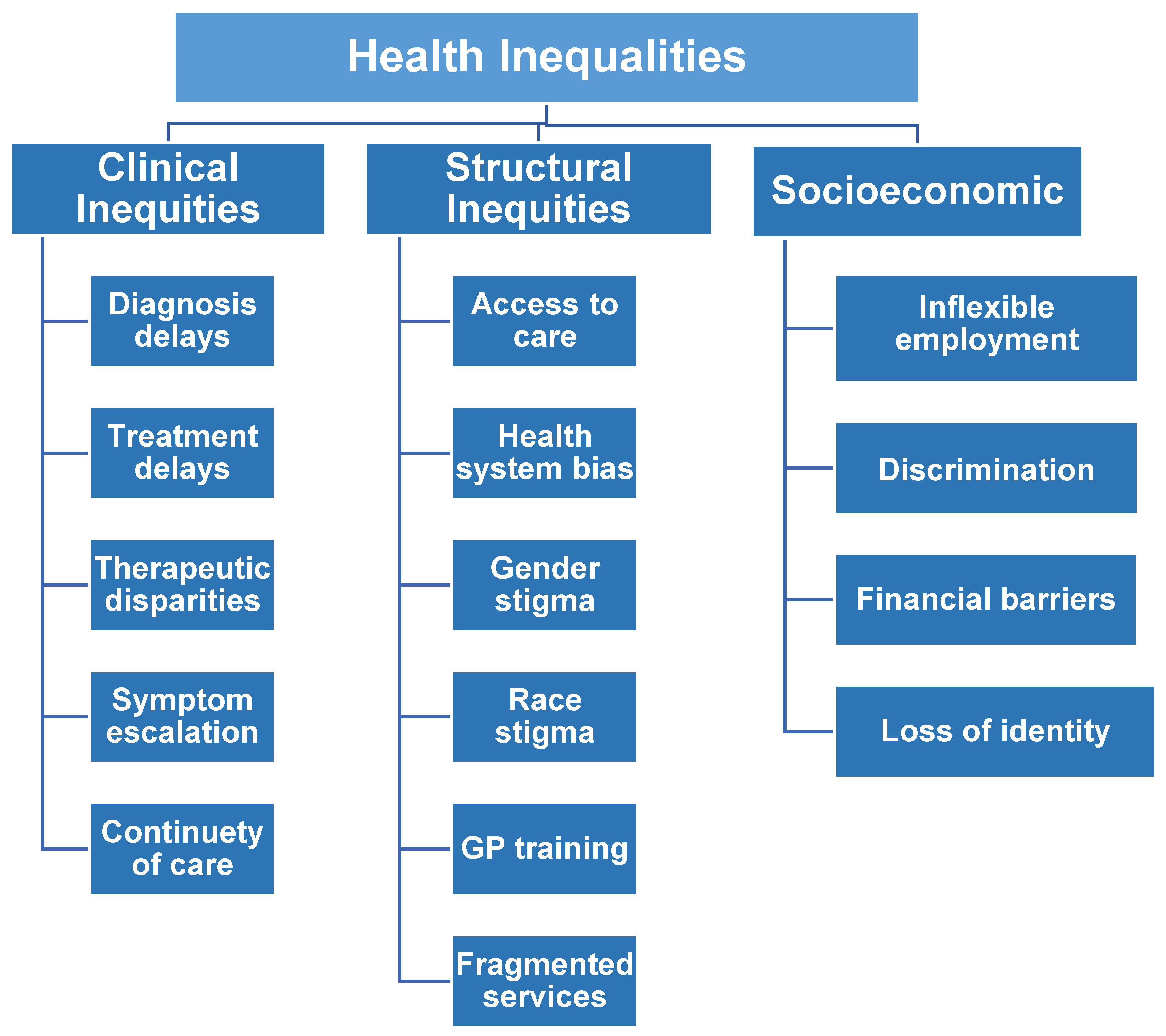

A characteristics table of the study sample and summary table of the themes and sub-themes (

Figure 1) are indicated in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

Clinical Care Inequities

Across all transcripts, a central and recurring theme was the pervasive inadequacy of clinical care during the menopausal transition. Participants reported delays in diagnosis, particularly where symptoms such as cognitive decline, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbance were misattributed to unrelated mental health conditions. Numerous individuals, including those with histories of depression or ADHD, were prescribed antidepressants or anxiolytics before menopause was considered, leading to a cascade of inappropriate treatments. In some cases, such as PID12 and PID13, delays in hormonal assessment contributed to suicidal ideation and prolonged psychological distress.

“Yeah, I went to them before for HRT cause likely it was definitely menopausal and even confirmed it was an bloods that but because it was moods that I was concerned about because I was snapping at my husband and I was really, I was more worried about that, then it was the antidepressant that was offered” PID12

"And I actually was so mentally unwell that I thought that I was going crazy and I was suicidal... And I was given antidepressants and beta blockers and diazepam and all sorts. No one even considered that this could be hormones. I wasn’t even perimenopausal apparently... until someone actually listened to me and gave me HRT, and within a week I felt like myself again." PID13

Participants highlighted the lack of training among general practitioners (GPs) in recognising and managing menopause, especially in cases of surgical or early menopause. Several described the inability of GPs to differentiate between hormonal symptoms and psychiatric or age-related conditions, while others noted their clinicians’ unfamiliarity with transdermal HRT, testosterone, or menopause in the context of complex multimorbidities. Individuals undergoing surgical menopause particularly after cancer or hysterectomy reported abrupt onset of symptoms without anticipatory guidance, post-operative support, or follow-up care. This clinical neglect left them to self-educate and self-advocate, often at great emotional and physical cost.

Structural and Systemic Barriers

Participants described multiple structural barriers to accessing timely and appropriate care. The GP-led model, while intended as a gateway to specialist services, functioned as a gatekeeping mechanism. Several women, such as PID26 and PID33, recounted being dismissed or triaged out of care by uninterested or ill-informed clinicians.

“I went to the GP four or five times, but every time they said it’s just stress or anxiety… I kept saying I think it's something else, but they just gave me sleeping tablets or said try yoga. I felt completely dismissed." PID26

"When I started having symptoms at 30, they didn’t believe it was menopause. I was told I was too young, that it was probably just depression or PMS. No one mentioned HRT until years later." PID33

In rural and remote regions including parts of Scotland the lack of menopause-informed specialists and service proximity further delayed access. PID46 and PID37 spoke of enduring months of debilitating symptoms before finally reaching a practitioner equipped to help.

"Living in rural Scotland meant my GP didn’t really know what to do… I had to wait nearly eight months before I saw someone who actually specialised in menopause. In the meantime, I was struggling to function at work." PID46

"It took me nearly a year before I found someone who actually linked my brain fog and mood swings to menopause. Before that, I thought I was just losing my mind. My GP kept brushing it off as stress."

A postcode lottery in HRT access emerged as a critical health inequality across the UK transcripts. Participants described inconsistent prescribing practices, regional delays, and disparities in access to menopause-informed clinicians. For example, those in rural Scotland (PID46) and northern regions reported long wait times and limited formulation options, while others in metropolitan areas secured timely, tailored care. These inconsistencies were exacerbated by GP gatekeeping, lack of national prescribing guidance enforcement, and economic barriers where private care filled NHS gaps. The resultant inequity reinforces geographic privilege, undermining universal healthcare principles and disproportionately disadvantaging women in marginalised or underserved areas.

Economic inequities emerged as a defining determinant of care quality. For participants unable to wait for NHS services or denied referrals, private healthcare was the only alternative. Yet this option was not universally accessible; those who accessed private menopause clinics expressed guilt and frustration about the inequity this introduced. Several participants, including PID17 and PID5, reflected that access to personalised, effective care should not be contingent on financial privilege.

"I eventually went private because I just couldn’t take it anymore. I felt guilty because I know not everyone can afford it. It shouldn’t have to come down to money just to be taken seriously and feel better." PID17

"I paid for a private consultation after being messed about for months. It was the first time anyone actually listened and understood. But why should it be this way? It’s not fair. People with less money are just left to suffer." PID5

Digital barriers also contributed to exclusion. Appointment systems reliant on online forms, automated calls, or limited consultation windows disadvantaged participants with caregiving responsibilities, mental health challenges, low digital literacy, or unstable internet access. For instance, PID24 noted that employment-related time pressures prevented her from engaging with e-consult systems, while PID8 described how linguistic and geographical factors created additional strain.

"The only way to get an appointment was through the e-consult, but by the time I finished work or looked after my mum, it was closed. I’d try in the morning and it would say all slots were gone. I just gave up some days." PID24

"I live quite far out and the internet’s patchy, so trying to do these online forms is a nightmare. And English isn’t my first language, so half the time I’m not sure what they’re even asking." PID5

Psychosocial and Identity-Based Inequalities

Menopausal distress was often compounded by psychological vulnerability, cultural expectations, and identity-related marginalisation. Several participants recounted suicidal ideation, panic attacks, emotional numbness, and intrusive thoughts that went unrecognised or unsupported. Mental health symptoms were frequently disconnected from underlying hormonal shifts, and psychiatric referrals were offered in lieu of endocrine assessments. The absence of trauma-informed, hormone-literate mental health care was especially damaging for participants with comorbid conditions, such as PID28 (fibromyalgia, PTSD) and PID40 (Crohn’s disease, depression).

"I kept saying something wasn’t right—panic attacks, crying spells, like I wasn’t in my own body. They sent me to mental health services, but no one talked about hormones. With fibromyalgia and PTSD, everything gets lumped together. I was drowning and nobody saw it." PID28

"I honestly thought I was losing my mind. I had suicidal thoughts and terrible brain fog. My GP suggested antidepressants and counselling, but never once mentioned hormones. With Crohn’s and everything else, I felt invisible." PID40

Transgender participants (PID32 and PID36) described the complete absence of menopause-competent, gender-affirming care. They experienced system-level misgendering, confusion about hormone monitoring, and fragmentation between primary and specialist care. These challenges were exacerbated by financial constraints, workplace invisibility, and a lack of tailored support. Their narratives underscore how health systems that are designed for cisgender bodies fail to accommodate diverse hormonal journeys.

"No one seemed to know what to do with me. My GP misgendered me in the notes, and when I asked about how reducing oestrogen might affect me, they just shrugged. I kept getting bounced between endocrinology and primary care it was exhausting." PID32

"I couldn’t afford to see anyone privately, and the NHS had no idea what to do with someone like me. At work, I didn’t tell anyone what I was going through—I just disappeared. There’s no space for trans people in the menopause conversation." PID36

Cultural and racial inequalities were also prominent. PID25, a South Asian woman, and PID47, who is obese and on a bariatric pathway, described stigma and judgment in clinical encounters. The dismissal of weight-related menopause symptoms, coupled with racist assumptions and implicit bias, delayed their access to respectful, competent care. These accounts reveal how intersecting forms of discrimination based on race, weight, gender identity, or reproductive history interact with clinical structures to amplify harm.

"I kept being told it’s just my culture, that I should expect to be tired and emotional because I’m a woman and I’m brown. It felt like they weren’t even listening—like they’d already decided what was wrong with me before I spoke." PID25

"I mentioned the brain fog and anxiety, and they just said it’s probably because of my weight. It’s always about the weight. I’m on the bariatric list, but I’ve been waiting for years. I don’t think they see me as a real menopause patient." PID47

Workplace Inequities and Policy Deficits

Participants reported that workplaces across the public and private sectors were largely unprepared to support menopausal individuals. Despite the growing recognition of menopause as a workplace issue, few participants had access to formal menopause policies, structured accommodations, or performance adjustments. Symptoms such as brain fog, incontinence, emotional volatility, and insomnia contributed to disciplinary action, demotion, or self-imposed withdrawal from work. For instance, PID23, a psychologist, was threatened with demotion for performance issues later attributed to untreated menopause. PID44 and PID40, both former NHS workers, retired early due to the lack of occupational flexibility and systemic understanding.

"I was forgetting things constantly, zoning out in meetings, and struggling to keep up. My manager said I might need to be moved to a lower banding. I didn’t even know it was menopause until months later. No one mentioned it, and there was no policy to protect me." PID23

"I was a senior midwife, but I had to step down. Between the hot flushes, bladder issues, and brain fog, I just couldn’t keep up with the pace. There was no flexibility, no understanding. I felt like I had no choice but to leave." PID44

"I had to leave the NHS. My memory was shot, I was crying at work, and nobody knew what to do with me. They sent me to occupational health, but even they didn’t understand menopause properly. I lost a job I loved because of ignorance." PID40

Even in NHS-affiliated roles, menopause support varied dramatically by department, manager, and geography. While some participants (PID29 and PID41) benefitted from compassionate line management or peer-led menopause cafés, these were exceptional rather than standardised. Most described informal knowledge sharing via Facebook groups, private forums, or charity networks. These substitute support systems were vital but underscored the absence of institutional accountability.

"My line manager was amazing, she let me adjust my hours when the insomnia got really bad. But that was just her being kind, not because there was a policy. If she wasn’t there, I don’t know what I’d have done." PID29

"We had a menopause café at work, which helped me feel less alone. But I learned more from Facebook groups and charity websites than from any official NHS resource. There’s just no consistent support—depends on where you work and who’s in charge."PID41

The cumulative impact of clinical, structural, and occupational exclusion led many participants to adopt self-management strategies through exercise, diet, supplements, or advocacy. Yet these solutions often required significant health literacy, economic means, and emotional resilience, illustrating a structural failure to meet the needs of vulnerable or under-resourced individuals.

Cross-Cutting Inequalities

The narratives revealed that health inequalities in menopause are not siloed but cross-cutting and cumulative. Participants who experienced early, surgical, or complex menopause described particularly acute vulnerability, often navigating the transition without tailored protocols or adequate clinician awareness. Others described how their symptoms were made invisible due to gender, race, class, comorbidities, or disability.

Reproductive injustice was a common experience among those with premature ovarian failure (PID33), endometriosis (PID49), or cancer-induced menopause (PID42). The emotional toll of reproductive loss was compounded by the structural invisibility of these experiences within clinical care and workplace policy.

"I went into menopause at 30. Nobody talked to me about what that would mean—not for my health, not for my future, not for my fertility. I was grieving, but there was no space for that grief anywhere in the system." PID33

"After chemo and the oophorectomy, everything just stopped. I wasn’t offered counselling, no one explained the menopause side of things. I couldn’t take HR

T because of the cancer, but there were no other options. Work didn’t get it either—they just saw me as unreliable."PID42

"They ignored my pain for years, then suddenly it was all too late. I had surgery and woke up in menopause. I didn’t get a chance to plan, to think about kids. That decision was taken out of my hands, and no one helped me process that."PID49

Peer support, although informal, was often more impactful than formal services. Participants repeatedly cited other women as their primary source of information, validation, and strategy. This points not only to the resilience of those affected, but also to a failure of systems to meet basic informational and emotional needs during menopause.

Discussion

Our qualitative analysis of 50 transcripts uncovers a vivid portrait of entrenched health inequalities in menopause care across the UK. Women consistently reported systemic disparities rooted in geography, socioeconomic status, and identity. Clinical barriers such as delayed diagnoses, GP misinformation, and a lack of surgical menopause protocols were intertwined with structural exclusion, including postcode-dependent access to HRT, fragmented services, uneven specialist availability, and digital or linguistic obstacles. Psychosocial distress was often amplified by gendered, racial, or identity-based stigma, with marginalized individuals bearing compounded burdens. Occupational consequences were profound; many were forced into career disruptions due to unsupported symptoms and absent workplace policies. These findings not only echo but also extend existing UK literature, providing rich, intersectional insights into lived experiences of inequality many of which remain invisible in large-scale quantitative studies. Notably, our data reveal nuanced patterns in underrepresented groups, such as trans, racialised, surgical menopause, and rural cohorts, offering novel evidence for targeted reform.

Clinical-level Implications

Across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, our findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive clinician training, enhanced menopause literacy, and proactive diagnostic protocols. National frameworks such as NICE’s

Menopause: Diagnosis and Management guidelines provide valuable direction, yet our cases reveal inconsistent application particularly in areas lacking integrated menopause clinics [

19]. The All-Party Parliamentary Group has long highlighted postcode disparities in specialist access, but our qualitative data illuminate the emotional toll of such gaps. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, devolved initiatives such as free HRT and Women’s Health Hubs show promise, yet clinical inertia persists especially in rural settings (e.g., PID46) [

20]. In Wales, dedicated GP upskilling is unevenly implemented [

21]. Our analysis is unique in highlighting clinician-level misdiagnosis of menopause as psychiatric disorders, and the invisibility of non-HRT options insights rarely captured in national audits.

Population-Level Implications

The UK’s population is extraordinarily diverse, encompassing 287 distinct ethnic groups according to ONS data, representing a wide array of cultural, linguistic, and historical backgrounds [

22]. Our analysis uniquely captures how menopause-related health inequalities are experienced across this rich tapestry of identities—highlighting nuances often overlooked in large-scale datasets.

The King’s Fund emphasised that structural racism profoundly shapes health inequities, affecting not only outcomes but also healthcare access, trust, and engagement[

23] . Our study vividly illustrates these dynamics in menopause care: individuals from minoritised backgrounds described cultural silencing of menopausal symptoms, linguistic miscommunication, and distrust rooted in past healthcare discrimination. These narratives align with the Health Security Agency’s findings of stark ethnic disparities in disease burden and hospitalisation, which are partially rooted in systemic inequities .Crucially, our qualitative data goes beyond epidemiological patterns to reveal intersectional layers from racial and cultural stigma to trans identity and socioeconomic vulnerability shaping how menopause is experienced and treated. This deep, lived insight is unprecedented in UK menopause research and underscores the urgent need for culturally tailored, anti-racist menopause care across all 287 ethnic groups.

Policy-Level Implications

At the policy level, the call to eliminate postcode lotteries is longstanding where the APPG reports highlighted the urgency for reform. Universal menopause health checks at age 45, as described by the APPG, nationally standardised formularies, and protected characteristic status under the Equality Act are uneven across the devolved nations in the UK.

Our findings document the negative consequences of supply chain failures and GP-based gatekeeping . We demonstrate unique evidence on how inconsistent local formularies narrow patient choice and fragment equity, strengthening the case for national HRT minimum datasets. Moreover, our study is the first to foreground occupational harms premature retirement, demotion, or workforce exit as direct outcomes of policy neglect, reinforcing the need for national workplace menopause guidelines and protections, especially in female-dominated sectors like healthcare and education.

Inclusive and representative research demands multidisciplinary teams combining healthcare professionals, patient and public involvement experts, and academics who themselves reflect the ethnic and gender diversity of the UK population. NIHR’s Race Equality Public Action Group emphasizes the importance of co-developing research tools with diverse communities, promoting inclusion at every stage [

24]. Embedding equity, diversity, and inclusion from design through implementation ensures research is more culturally responsive and trustworthy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that ethnically diverse scientific collaborations significantly increase research impact both in citations and in advancing innovation. A diverse team also helps build rapport with historically marginalised communities, fostering trust that’s essential for authentic engagement and equitable outcomes.

Our research is uniquely positioned to inform transformative change, offering unprecedented qualitative insight into the intersectional and identity-driven drivers of inequity. We provide the following recommendations to address the menopause-related health inequalities (

Table 3);

Conclusion

Systemic health inequalities in menopause care appear to be deeply rooted in clinical misrecognition, geographic disparities, socioeconomic exclusion, and workplace neglect. Women from diverse backgrounds especially those undergoing surgical or early menopause, living rurally, or belonging to minoritised groups face compounded barriers in accessing timely, culturally competent care. These lived experiences underscore critical policy failures in implementing equitable access, reinforcing postcode-based disparities. Targeted reforms in clinician training, inclusive service delivery, and menopause-aware workplace policies are urgently needed to uphold the principle of equitable care for all UK women undergoing menopause.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Code availability

Not applicable

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. GD, KE, PP, JT, LS and HFK submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study. KM, VC, LS, KR, SH, KP, GD, PP, VT, RP and HFK collected data. GD and JQS conducted the data analysis. GD wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP and PP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales Approval (22/EE/0158)

Consent to participate

Obtained

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

Acknowledgements: MARIE Consortium

Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Kathleen Riach, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Ganesh Dangal, Om Kurmi, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani and Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Fred Tweneboah-Koduah, Nana Afful-Minta, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Chukwuemeka Chijindu Njoku, Bernard Mbwele, David Chibuike Ikwuka, Pradip K Mitra, Cristina Benetti-Pinto, Rukshini Puvanendram, Manisha Mathur, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Farah Safdar, Raksha Aiyappan, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel, Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma, Francisca Ndubuisi, Baraka Godfrey Mwahi, Filbert Francis Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Clement Mwabenga, Mpoki Kaminyoghe, Brenda Mdoligo, Thomas Alone Saida, Nicodemus E. Mwampashi

References

- Local Government Association. Menopause Factfile [Available from: https://local.gov.uk/our-support/workforce-and-hr-support/wellbeing/menopause/menopause-factfile.

- Greendale GA, Lee NP, Arriola ER. The menopause. The Lancet. 1999;353(9152):571-80.

- Sherman S. Defining the menopausal transition. The American journal of medicine. 2005;118(12):3-7. [CrossRef]

- McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner JG. The normal menopause transition. Maturitas. 1992;14(2):103-15.

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, Talaulikar V, Eleje GU, Kareem R, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health. 2025;13(2):e196-e8. [CrossRef]

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, Hodis HN, Johnson AE, Langer RD, et al. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(25):e506-e32. [CrossRef]

- Than S, Moran C, Beare R, Vincent A, Lane E, Collyer TA, et al. Cognitive trajectories during the menopausal transition. Frontiers in dementia. 2023;2:1098693. [CrossRef]

- Lobo RA, Gompel A. Management of menopause: a view towards prevention. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022;10(6):457-70. [CrossRef]

- Than S, Moran C, Beare R, Vincent AJ, Collyer TA, Wang W, et al. Interactions between age, sex, menopause, and brain structure at midlife: a UK Biobank study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021;106(2):410-20. [CrossRef]

- Kalita K, Raina D, Mall P. The Basics of Perimenopause: Menopause and Pre-Menopause. Utilizing AI Techniques for the Perimenopause to Menopause Transition: IGI Global; 2024. p. 1-25.

- Hamoda H, Moger S, Morris E, Baldeweg S, Kasliwal A, Gabbay F, et al. Menopause practice standards. Post Reproductive Health. 2022;28(3):127-32. [CrossRef]

- Sharman Moser S, Chodick G, Bar-On S, Shalev V. Healthcare utilization and prevalence of symptoms in women with menopause: a real-world analysis. International journal of women's health. 2020:445-54. [CrossRef]

- CIPD Media Centre. Over a quarter of women say menopause has had a negative impact on career progression. 2023.

- Almeida L. Menopause ‘pension penalty’ costs women £30,000 in retirement. The Telegraph. 2023.

- Crown Office & Procurator Fiscal Service. Menopause policy equality impact assessment. 2023.

- Westwood S. ‘GP services are still heteronormative’: Sexual minority cisgender women’s experiences of UK menopause healthcare–Health equity implications. Post Reproductive Health. 2024;30(4):225-31.

- Eder C, Roomaney R. Transgender and non-binary people’s experience of endometriosis. Journal of Health Psychology. 2025;30(7):1610-23. [CrossRef]

- Nowaskie DZ, Menez O. Healthcare experiences of LGBTQ+ people: non-binary people remain unaffirmed. Frontiers in Sociology. 2024;9:1448821. [CrossRef]

- Lumsden MA, Davies M, Sarri G. Diagnosis and management of menopause: the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline. JAMA internal Medicine. 2016;176(8):1205-6.

- Daniel K, Bousfield J, Hocking L, Jackson L, Taylor B. Women’s Health Hubs: a rapid mixed-methods evaluation. Health and Social Care Delivery Research. 2024;12(30):1-138. [CrossRef]

- Group A-WMTaF. All-Wales Menopause Task and Finish Group, Final Report, January 2023. Welsh Government; 2023.

- Office for National Statistics. Ethnic group, England and Wales: Census 2021.

- The King's Fund. What are health inequalities? 2025 [Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/what-are-health-inequalities?

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. NIHR publishes framework to promote race equality in public involvement in research 2022 [Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/news/nihr-publishes-framework-promote-race-equality-public-involvement-research?

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).