Background

Menopause, whether occurring naturally, or induced through medical or surgical intervention, represents a universal yet highly individual health transition, defined clinically as the absence of menstruation for 12 consecutive months in the absence of other causes [

1,

2]. This transition spans a continuum,

perimenopause, characterised by fluctuating hormones and irregular cycles;

menopause, marking the final menstrual period; and

post-menopause, where symptoms may persist and long-term health risks emerge [

3,

4,

5]. Abrupt onset following interventions such as bilateral oophorectomy, chemotherapy, or pelvic radiotherapy often precipitates more severe symptom profiles and distinct care needs compared with gradual, natural transition [

6].

Public and clinical discourse frequently centres on vasomotor symptoms and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) access, yet this narrow framing obscures the broader burden [

7,

8]. Cognitive decline, mood disturbance, musculoskeletal pain, urogenital dysfunction, and increased long-term risks related to cardiometabolic, autoimmune, and neurological conditions are common and often compounded in those with pre-existing comorbidities. Individuals experiencing medical or surgical menopause frequently face sudden symptom escalation with limited preparatory information or tailored support [

9].

An intersectional perspective highlights how clinical challenges are intensified by structural and social inequities [

10,

11]. Socioeconomic disadvantage, occupational instability, cultural stigma, racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and treatment, neurodivergence, and histories of trauma interact to shape both the experience of symptoms and access to care [

10]. The Delanerolle and Phiri Framework, comprising four interdependent domains of

Biological, Psychological, Socio-cultural, and

Health System, captures these overlapping influences, reframing menopause as a convergence of lifetime health trajectories, mental wellbeing, cultural norms, and health system responsiveness [

12].

Despite increasing public awareness and recent UK policy reforms aimed at expanding HRT provision and menopause education, current strategies fail to address the diversity of symptom profiles, the high burden of comorbidity, and the compounded disadvantages faced by marginalised populations. Individuals with long-term mental health conditions, rare diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, or treatment-induced menopause remain at particular risk of unmet needs [

13].

Rationale

This study applies a qualitative, intersectional-informed analysis to chart the experiences of perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause across natural, medical, and surgical pathways. It examines how biological, psychological, socio-cultural, and health system factors interact to shape symptom severity, comorbidity burden, and access to care. By centring participant narratives, the study generates evidence to inform responsive clinical service design and targeted policy interventions. While grounded in the UK context, the findings have international relevance, offering a framework for equitable, context-sensitive menopausal care across diverse health systems.

Methods

Design

A secondary qualitative analysis was conducted using 50 semi-structured interviews from the MARIE UK WP2a study. Participants included cisgender and transgender individuals aged 35–70 who had experienced perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause through natural, medical, or surgical pathways.

Framework

Qualitative data were analysed using the Delanerolle and Phiri Framework, a structured model incorporating four interrelated domains of Biological, Psychological, Socio-cultural, and Health System. This framework was selected for its capacity to integrate biomedical, psychosocial, and structural determinants of health, allowing for systematic exploration of symptom profiles and care experiences.

The Biological domain captured physiological mechanisms, hormonal changes, and coexisting medical conditions influencing symptom severity and trajectories. The Psychological domain encompassed cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions, including the influence of stress, trauma, and pre-existing mental health conditions. The Socio-cultural domain examined the role of cultural norms, gendered expectations, stigma, and socioeconomic status in shaping health behaviours and access to care. The Health System domain interrogated the organisation, quality, and accessibility of services, clinician expertise, and systemic barriers to timely and equitable treatment.

Data Analysis

All transcripts were deductively coded into the four domains. Within each domain, content analysis was used to identify comorbidities, symptom patterns, and severity (mild, moderate, severe). Symptom severity was cross-mapped with participants’ comorbidity profiles and the health system responses they received. NVivo was used to manage the data. A thematic synthesis followed, integrating narrative quotes, frequency counts, and participant-reported impact across domains. A final cross-case matrix was developed to identify patterns and intersectional overlap.

Codes and sub-codes used for the scope of this study aligned to the Delanerolle and Phiri framework is shown in

Table 1.

Ethics

The study received integrated ethical and governance approval from the Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales (Reference: 22/EE/0158) and sponsorship from Hampshire and Isle of Wight Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (formally Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

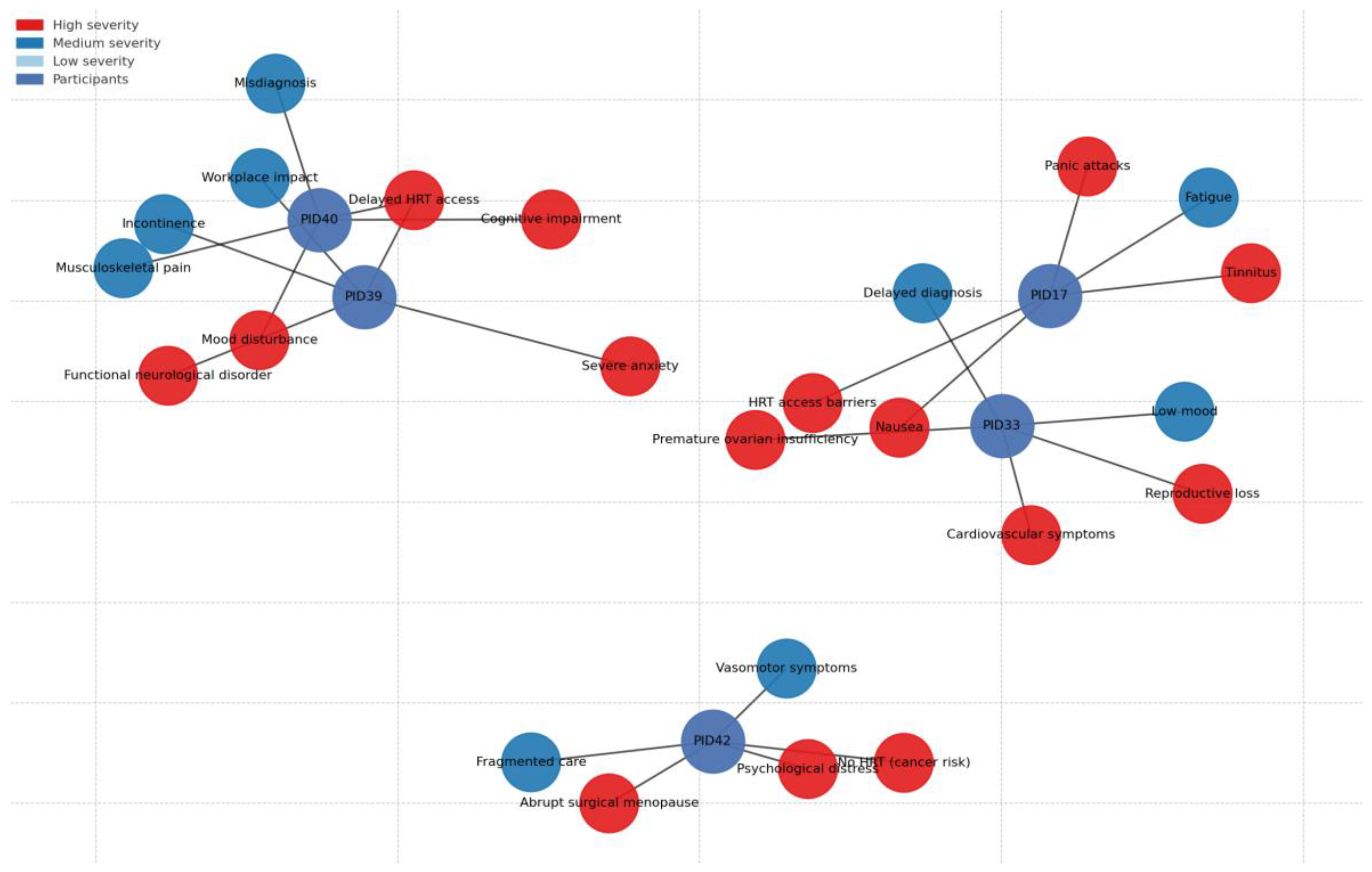

A characteristics table of the study (

Table 2) explain the sample. Thematic analysis revealed marked disparities in menopausal symptom experience, care access, and support, strongly shaped by intersecting biological, psychological, socio-cultural, and systemic factors (

Table 3;

Figure 1). Intersectional disadvantages arising from the overlap of comorbidity, neurodivergence, socioeconomic deprivation, and marginalised identities were evident across all domains.

Biological Domain

Participants with cardiometabolic, autoimmune, and endocrine disorders reported severe or accelerated menopausal symptoms that were frequently misattributed to existing conditions, delaying appropriate intervention. Abrupt hormonal withdrawal following BRCA-related surgery or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) led to sudden, debilitating symptoms and elevated long-term health risks.

“I went through it early… but nobody explained why my heart was racing. I thought I was dying.” (PID33)

“I’ve got diabetes and Crohn’s, so when the hot flushes and night sweats started, they thought it was infection. It wasn’t—it was menopause.” (PID40)

The absence of multidisciplinary coordination left many managing complex, overlapping conditions without integrated support. For some, menopause appeared to exacerbate baseline disease activity, including interstitial cystitis and cardiovascular instability.

Pre-existing comorbidities and abrupt hormonal changes heightened physical symptom burden.

“The pain and tiredness I already had got worse overnight—like someone had turned the volume up on everything.” (PID2)

“I’d stand up and the room would spin, but no one thought it was menopause-related.” (PID30)

“The joint pain after menopause became relentless—painkillers just didn’t touch it anymore.” (PID7)

“One day I was fine, the next I was drenched in sweat every hour—my body went into shock.” (PID22)

“The heat and sweating were unbearable—I’d have to change clothes three times a night.”(PID27)

Menopausal symptoms emerged within the context of complex multimorbidity, including head and neck cancer treated with high-dose radiotherapy, thyroid dysfunction, long-term Mirena coil use, and historical heavy menstrual bleeding. Early symptoms were mild and managed with oestradiol and the Mirena coil, but severity escalated in late 2022–2023, with persistent nausea (a known trauma trigger from hyperemesis gravidarum), tinnitus, fatigue, and low energy. Symptom attribution was complicated by oncology sequelae, delaying targeted intervention and increasing cumulative symptom burden.

“The nausea was getting intolerable… I’ve had really bad hyperemesis gravidarum with both my pregnancies… feeling nauseous is a bit of a trigger for me.” (PID17)

Psychological Domain

Cognitive dysfunction and psychological symptoms memory lapses, word-finding difficulties, mood instability were described as among the most distressing yet least understood aspects of menopause. Intersectional vulnerability was acute for those with pre-existing mental health diagnoses, trauma histories, or neurodivergence.

“I lost my words in meetings. I thought I had dementia. It terrified me.” (PID40)

“I already had mental health issues, but menopause sent me into a spiral. I didn’t want to live.” (PID38)

“I’m autistic—change is hard enough, but this felt like my brain was being rewired overnight. My GP didn’t believe menopause could do that.” (PID47)

For neurodivergent participants, menopausal cognitive changes amplified sensory and executive function challenges, often leading to medical dismissal or misdiagnosis. Psychological distress was frequently treated as unrelated to menopause, and specialist referrals were rare. The lack of integrated menopause–mental health pathways emerged as a recurrent structural gap.

Mental health vulnerabilities compounded the impact of physical symptoms.

“Every time I lost my words at work, my heart sank. I thought—what if this is dementia?” (PID13)

“The lack of sleep and pain pushed me into a dark place. I didn’t want to get out of bed.”(PID7)

“I already struggle to process too much information—brain fog made everything overwhelming.”(PID27)

“The panic attacks came back worse than before—it was like my body remembered every bad thing at once.”(PID2)

“I’d wake up at 3 a.m. panicking about forgetting something important—it made the brain fog even worse.”(PID30)

The severity of her cognitive and emotional symptoms escalated alongside physical changes. She reported heightened anxiety, panic attacks linked to tinnitus, low mood, and difficulty processing care disruptions possibly amplified by her suspected ADHD or other neurodivergent traits. Her account suggested sensory sensitivity and rigidity around treatment routines, with significant psychological distress triggered by the prospect of HRT regime changes.

“I’m autistic—change is hard enough, but this felt like my brain was being rewired overnight. My GP didn’t believe menopause could do that.”“The prospect of having to change my HRT really sent me in quite a bad spiral… I just couldn’t cope with it.” (PID17)

Socio-Cultural Domain

Workplace discrimination, gendered stigma, and social invisibility defined much of the socio-cultural experience. Participants described masking symptoms in professional settings, leading to presenteeism, performance decline, and, in some cases, job loss.

“No one at work talks about it… only the online groups got me through.” (PID29)

“I was a senior clinician, but when I started forgetting things, I felt ashamed. I didn’t tell anyone.” (PID44)

Early or surgical menopause brought additional grief related to reproductive loss, compounded by silence and marginalisation. Peer networks Facebook groups, WhatsApp chats, charity forums emerged as essential spaces for validation and knowledge exchange, underscoring the failure of mainstream services to meet cultural and emotional needs.

Workplace expectations and social stigma forced participants to conceal symptoms.

“I smiled through it at work, but inside I was counting the minutes until I could get home.”(PID30)

“After surgery, people expected me to just get on with things—cooking, looking after everyone—no one asked how I was coping.”(PID22)

“People judged me for my weight, so I kept quiet about the sweats and exhaustion.”(PID27)

“Friends just didn’t get it. I stopped talking about it and found comfort online instead.”(PID2)

Although not currently in formal employment, PID17’s workplace observations revealed a growing but inconsistent recognition of menopause, often driven by external social pressure rather than embedded policy. She noted the absence of formal menopause support during her working life and highlighted how informal networks (e.g., forums, peer discussions) remain vital sources of information and solidarity. Her account linked structural decision-making about drug licensing and prescribing rules to feelings of disempowerment and loss of agency.

“Decisions are made about our health and well-being, and we don’t have a say in it at all.” (PD17)

Health System Domain

Care pathways were characterised by delays, contradictions, and inequitable access. Many were denied HRT due to comorbidities without alternative management plans; others navigated conflicting advice across general practice, gynaecology, and mental health services.

“I was a midwife, but when it hit me, no one could help. I felt betrayed by the system I’d served.” (PID44)

“My GP just kept saying it was stress. I was crying every day, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t think straight, and still—no HRT.” (PID39)

Rural and underserved populations faced heightened barriers, with some accessing timely support only through personal networks or private care. Intersectional disadvantage was particularly evident where health system fragmentation overlapped with socioeconomic constraints, racial marginalisation, or neurodivergence, compounding both clinical and emotional harm.

The severity in symptoms was exacerbated by systemic failures. A service gap in Mirena coil provision for HRT purposes, caused by policy changes shifting insertion to sexual health clinics without integrated menopause care. This discontinuity triggered high anxiety and reinforced feelings of being “lost in the system.” recounting funding refusals for menopause-specific GP training, inconsistent HRT availability, and restricted access to testosterone treatments such as Androfeme.

“Somebody sitting in an office somewhere taking these decisions away from me… I feel strongly that this is a massive gap within women’s health.” (PID17)

The capacity to self-fund private consultations buffered the worst impacts, but she expressed guilt knowing most women could not do the same framing this inequity as a moral and systemic failing. These findings illustrates how high symptom severity both physical (nausea, tinnitus, fatigue) and psychological (panic, anxiety, cognitive disruption) can emerge from the interaction of complex medical histories, suspected neurodivergence, and rigid or inaccessible care pathways. Her experience demonstrates that severity is not only a function of hormonal change but is magnified by trauma triggers, sensory sensitivities, service fragmentation, and loss of patient agency. Within the Delanerolle & Phiri framework, her account spans all four domains, with particular emphasis on the health system domain as an active driver of symptom escalation.

Gaps in clinical pathways often prolonged or worsened symptoms.

“One doctor told me I needed HRT, another said no—it went on for months while I struggled.”(PID30)

PID22 said, “They kept saying it was too soon after surgery for HRT, but the symptoms were unbearable.”

PID7 recalled, “I had to fight for every appointment—by the time I got one, the pain was constant.”

PID27 noted, “There’s no menopause clinic near me. My GP tries, but they don’t have the training.”

PID2 explained, “They told me it was just ageing—I believed them until I couldn’t function anymore.”

“Every time I saw a new doctor, I had to start my story again—no one joined the dots.”(PID13)

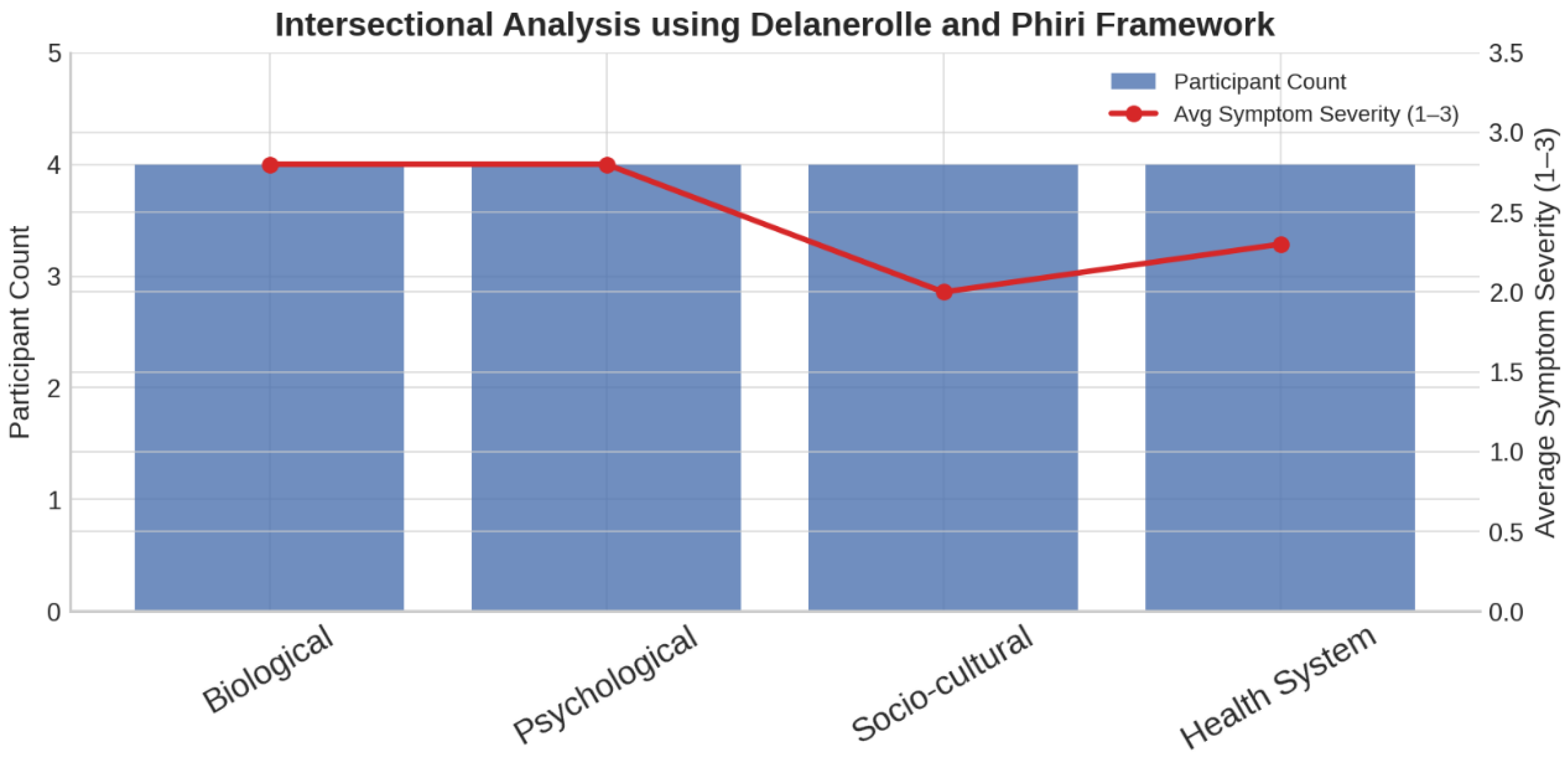

Average symptom severity scores were highest in the

Biological and Psychological domains (

Figure 2), suggesting these areas had a more profound symptom impact. In contrast, the

Socio-cultural domain showed the lowest average severity, while the

Health System domain exhibited a moderate increase, reflecting the interplay between structural barriers and symptom experience.

Discussion

Intersectionality, applied through qualitative methodologies, offers a critical lens to examine the compounded effects of social positioning, structural discrimination, and clinical marginalisation in women’s health. In the context of menopause, qualitative approaches capture nuanced lived experiences that remain obscured by biomedical metrics alone. The Delanerolle and Phiri Framework, which categorises inequalities across four intersecting domains of

biological, psychological, socio-cultural, and

health system has revealed how comorbidities, stigma, and fragmented care pathways influence both symptom burden and access to quality care [

12].

In the UK, where menopause has entered mainstream discourse, our findings challenge the adequacy of one-size-fits-all policies. Standardised approaches overlook the needs of individuals with neurodivergence, chronic illness, or reproductive trauma, and risk exacerbating inequities. An intersectional perspective is therefore essential to achieving equity in clinical practice, education, and service delivery. Without it, the most vulnerable populations remain underserved despite policy advances.

Clinical Impact

This study demonstrates that the severity and management of menopausal symptoms are shaped by the interaction between co-existing health conditions and social identities. Participants with cardiometabolic disease, neurodevelopmental disorders, or complex trauma histories described amplified cognitive, emotional, and somatic symptoms, often compounded by diagnostic delays and fragmented treatment.

Current UK clinical pathways inadequately reflect this complexity. Menopause care remains siloed, with pharmacological management separated from mental and physical health support. This division neglects the biopsychosocial interplay central to menopause and disproportionately disadvantages racially minoritised, neurodivergent, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. For those declining pharmacological treatment, non-medical options are often limited to generic lifestyle advice or referrals to overstretched services, further entrenching barriers.

Integrated, trauma-informed, and person-centred models are required. Routine assessments should screen for mental health disorders, neurodiversity, histories of reproductive injustice, and social determinants of health. Clinicians must be equipped to deliver culturally competent, inclusive care that bridges physical and mental health, ensuring continuity and equity.

Beyond the Academic Impact

Despite an expanding evidence base, much menopause research remains disconnected from practice. Interventions, including digital platforms, pharmacological therapies, and educational tools are often developed without sustainable adoption plans, clear licensing pathways, or integration into NHS and community services. This limits their reach, undermines public trust, and wastes public investment. Industry-led solutions may offer alternatives, but concerns persist over data use, ownership, and potential harm.

The financial consequences of narrow, non-translational research are significant. Publicly funded projects that fail to embed sustainability risk duplicating efforts, burdening NHS services, and excluding underserved populations. Proprietary licensing models, poor interoperability, and limited clinical relevance reduce value for patients and clinicians, placing avoidable costs on the taxpayer. Narrow methodologies also perpetuate epistemic exclusion by under-representing racially minoritised, neurodivergent, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and LGBTQ+ populations in study design and dissemination.

A Paradigm Shift: The Delanerolle and Phiri Framework

The Delanerolle and Phiri Framework offers an integrated approach that addresses structural, clinical, and experiential complexity [

12]. Moving beyond frequency-based coding or abstracted thematic categorisation, it situates narratives within intersectional contexts, combining socio-structural mapping, experiential trajectory modelling, and translation into policy- and practice-ready outputs.

Socio-structural coding links participant experiences to determinants such as race, income, disability, and geography. Experiential trajectory modelling captures how menopause symptoms evolve across natural, surgical, premature, and medically induced pathways, shaping care access and self-management. Translation layering converts these data into actionable outputs, including tailored escalation pathways, culturally adapted communication prompts, and intersectionality-informed public health recommendations.

By retaining narrative complexity while structuring it for decision-making, the framework generates evidence capable of informing NHS practice, commissioning, and workplace policy, bridging the research–practice divide while embedding equity.

Healthcare Service Impact

Across primary, acute, community, and mental health services, we identified persistent fragmentation, insufficient training, and minimal accountability, particularly for individuals with multimorbidity, neurodivergence, or complex psychosocial histories.

In primary care, participants frequently reported symptom minimisation, misdiagnosis, and reluctance to prescribe HRT, especially in the presence of comorbidities. Antidepressants were often prescribed inappropriately, reflecting a lack of menopause-specific training. Acute care settings rarely recognised menopause as a contributing factor in presentations such as cognitive decline or cardiovascular events, leading to missed opportunities for prevention and delayed management. Community services were often inaccessible outside urban areas, with little integration across care settings. Mental health services operated in isolation from menopause care, failing to link psychological symptoms with hormonal changes, particularly in those with trauma histories.

Our intersectional, multisystem approach revealed how these deficits intersect, producing compounded disadvantage. The analysis identified actionable, system-specific gaps such as the absence of trauma-informed care in general practice, lack of neurodiversity awareness in mental health triage, and inadequate cultural adaptation in community outreach offering a roadmap for policy and commissioning reform.

Policy Impact

Current UK menopause policies inadequately address intersectional disparities [

14]. Future reforms must prioritise tailored workplace support, national clinical guidelines that account for diverse menopausal pathways, and equity-driven funding for menopause research. Expanding self-referral routes, implementing digital triage, and developing regional menopause hubs could help close access gaps. Global health systems can adapt these principles to embed intersectionality in policy, ensuring that menopause care is equitable, context-sensitive, and responsive to diverse lived experiences.

The IMS 2024 White Paper emphasises a biopsychosocial approach to menopause diagnosis and management, integrating biological, psychological, and social determinants to optimise care [

15]. This reflects a shift towards holistic, patient-centred models that account for individual symptom profiles, comorbidities, and contextual factors. In contrast, cognitive health in menopause, while increasingly recognised, remains an area with limited high-quality evidence, particularly regarding the role of HRT. The position statement of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) on hormone therapy on brain fog underscores that HRT should not be promoted primarily for cognitive benefit, given the paucity of robust data, and instead offers a practical toolkit for clinicians to assess and manage cognitive complaints through multidisciplinary and non-pharmacological strategies [

16]. Our findings build on these foundations, advancing the IMS approach by embedding intersectional health inequalities, lived experience insights, and cross-cultural perspectives, while operationalising findings into actionable, scalable interventions. The MARIE project takes the IMS vision ten steps further bridging evidence to real-world adoption, sustainability, and policy integration.

Conclusions

In the UK, menopausal symptom burden is intensified by intersecting comorbidities, neurodivergence, and structural inequities, while fragmented services perpetuate delays and mismanagement. Urgent, coordinated reform spanning clinical training, integrated care pathways, workplace policy, and equitable research funding is essential to ensure accessible, person-centred menopause care for all.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. GD, KE, PP, JT, LS and HFK submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study. KM, VC, LS, KR, SH, KP, GD, PP, VT, RP and HFK collected data. GD and JQS conducted the data analysis. GD wrote the first draft and was furthered by all other authors. VP and PP edited and formatted all versions of the manuscript. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales Approval (22/EE/0158).

Consent to participate

Obtained.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Kathleen Riach, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Ganesh Dangal, Om Kurmi, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani and Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Fred Tweneboah-Koduah, Nana Afful-Minta, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Chukwuemeka Chijindu Njoku, Bernard Mbwele, David Chibuike Ikwuka, Pradip K Mitra, Cristina Benetti-Pinto, Rukshini Puvanendram, Manisha Mathur, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Farah Safdar, Raksha Aiyappan, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel, Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma, Francisca Ndubuisi, Baraka Godfrey Mwahi, Filbert Francis Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Clement Mwabenga, Mpoki Kaminyoghe, Brenda Mdoligo, Thomas Alone Saida, Nicodemus E. Mwampashi.

References

- Ambikairajah, A.; Walsh, E.; Cherbuin, N. A review of menopause nomenclature. Reproductive health 2022, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greendale, G.A.; Lee, N.P.; Arriola, E.R. The menopause. The Lancet 1999, 353, 571–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redding, N. The Menopause Transition in a Relationship Context: Voices and Choices at Midlife, 1991-2012: Taylor & Francis; 2025.

- Cunningham, A.C.; Hewings-Martin, Y.; Wickham, A.P.; Prentice, C.; Payne, J.L.; Zhaunova, L. Perimenopause symptoms, severity, and healthcare seeking in women in the US. npj Women's Health 2025, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G.; Phiri, P.; Elneil, S.; Talaulikar, V.; Eleje, G.U.; Kareem, R.; et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 2025, 13, e196–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuster, L.T.; Rhodes, D.J.; Gostout, B.S.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A. Premature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequences. Maturitas 2010, 65, 161–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flore, J.; Kokanović, R.; Johnston-Ataata, K.; Hickey, M.; Teede, H.; Vincent, A.; et al. Care, choice, complexities: The circulations of hormone therapy in early menopause. The Sociological Review 2024, 72, 1193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, B.A. Intervention and (Re) Invention for Women in Menopause: Cultural Norms, Hormone Therapy and Female Subjectivity: University of Otago; 2012.

- Crandall, C.J.; Mehta, J.M.; Manson, J.E. Management of menopausal symptoms: a review. Jama 2023, 329, 405–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blais, A. Women, Menopause and Menopause Learning: A Critical Feminist Analysis. 2024.

- Cortés, Y.I.; Marginean, V. Key factors in menopause health disparities and inequities: beyond race and ethnicity. Current opinion in endocrine and metabolic research 2022, 26, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women's Health Research. 2025.

- Mansour, D.; Barber, K.; Chalk, G.; Noble, N.; Digpal, A.A.S.; Talaulikar, V.; et al. The evolving perspective of menopause management in the United Kingdom. Women's Health 2024, 20, 17455057241288641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westwood, S. A bloody mess? UK regulation of menopause discrimination and the need for reform. Journal of Law and Society 2024, 51, 104–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panay, N.; Ang, S.B.; Cheshire, R.; Goldstein, S.R.; Maki, P.; Nappi, R.E.; et al. Menopause and MHT in 2024: addressing the key controversies–an International Menopause Society White Paper. South African General Practitioner 2024, 5, 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, R.E. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society: no news is good news. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2022, 10, 832–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).