Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

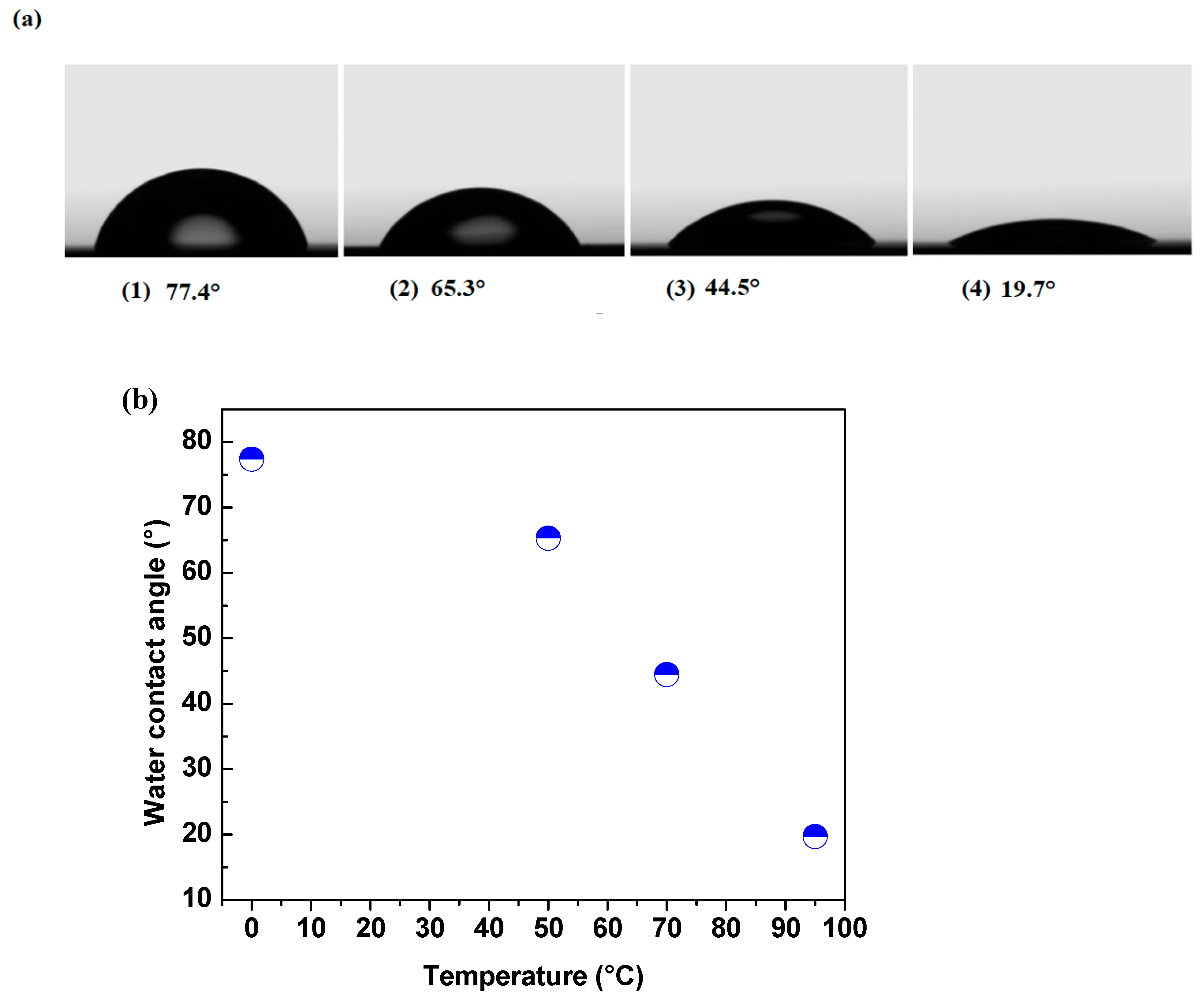

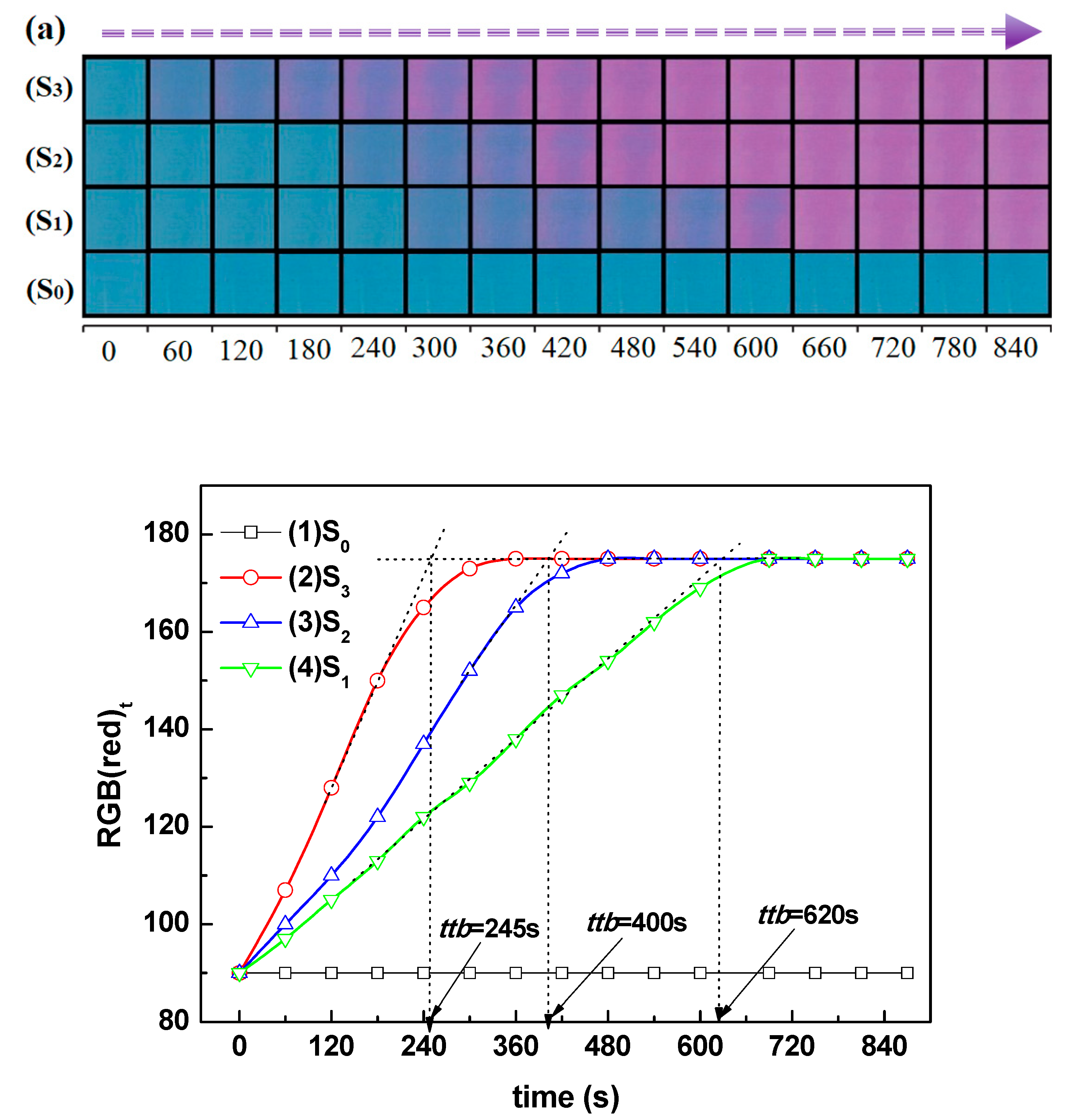

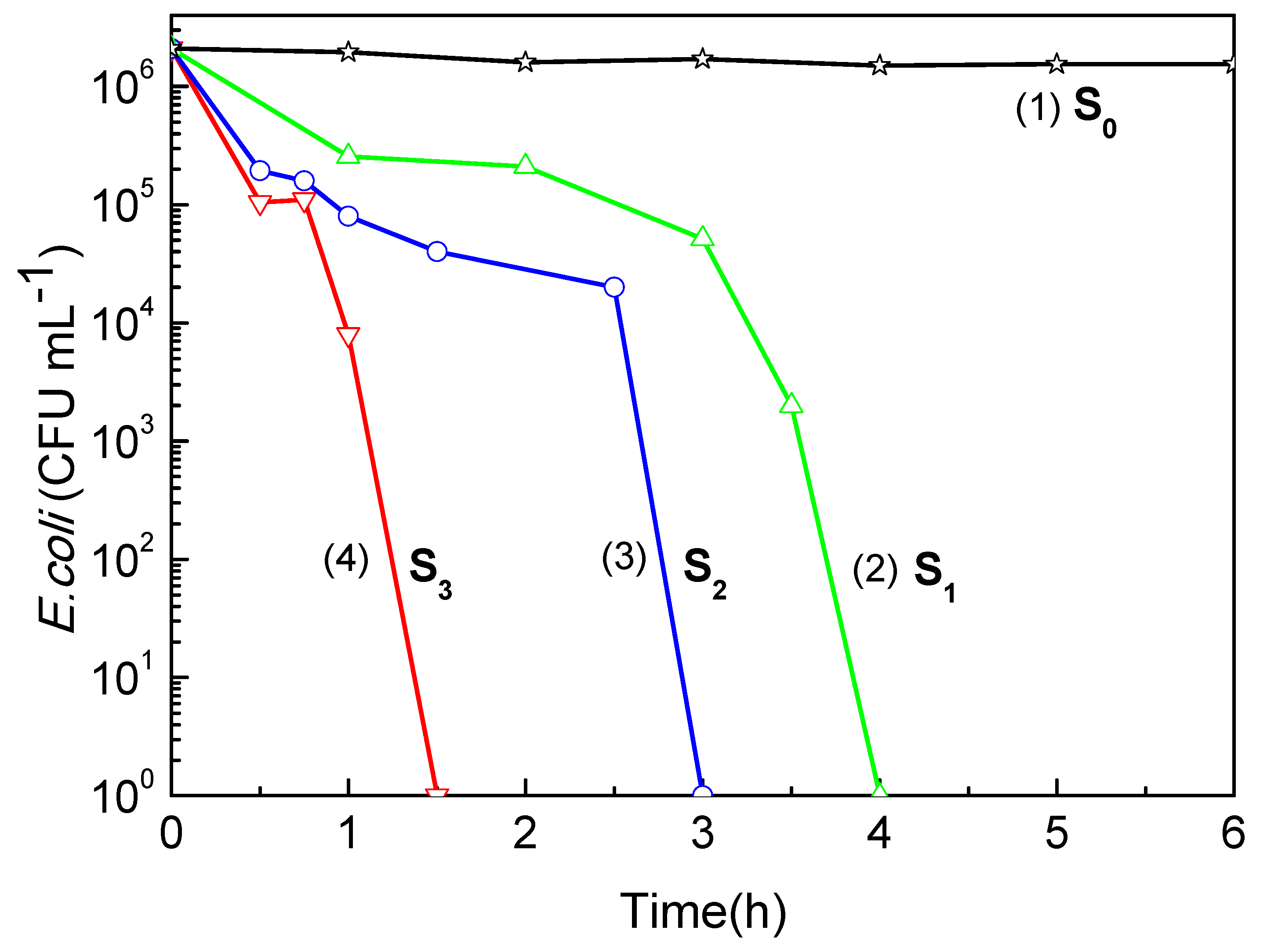

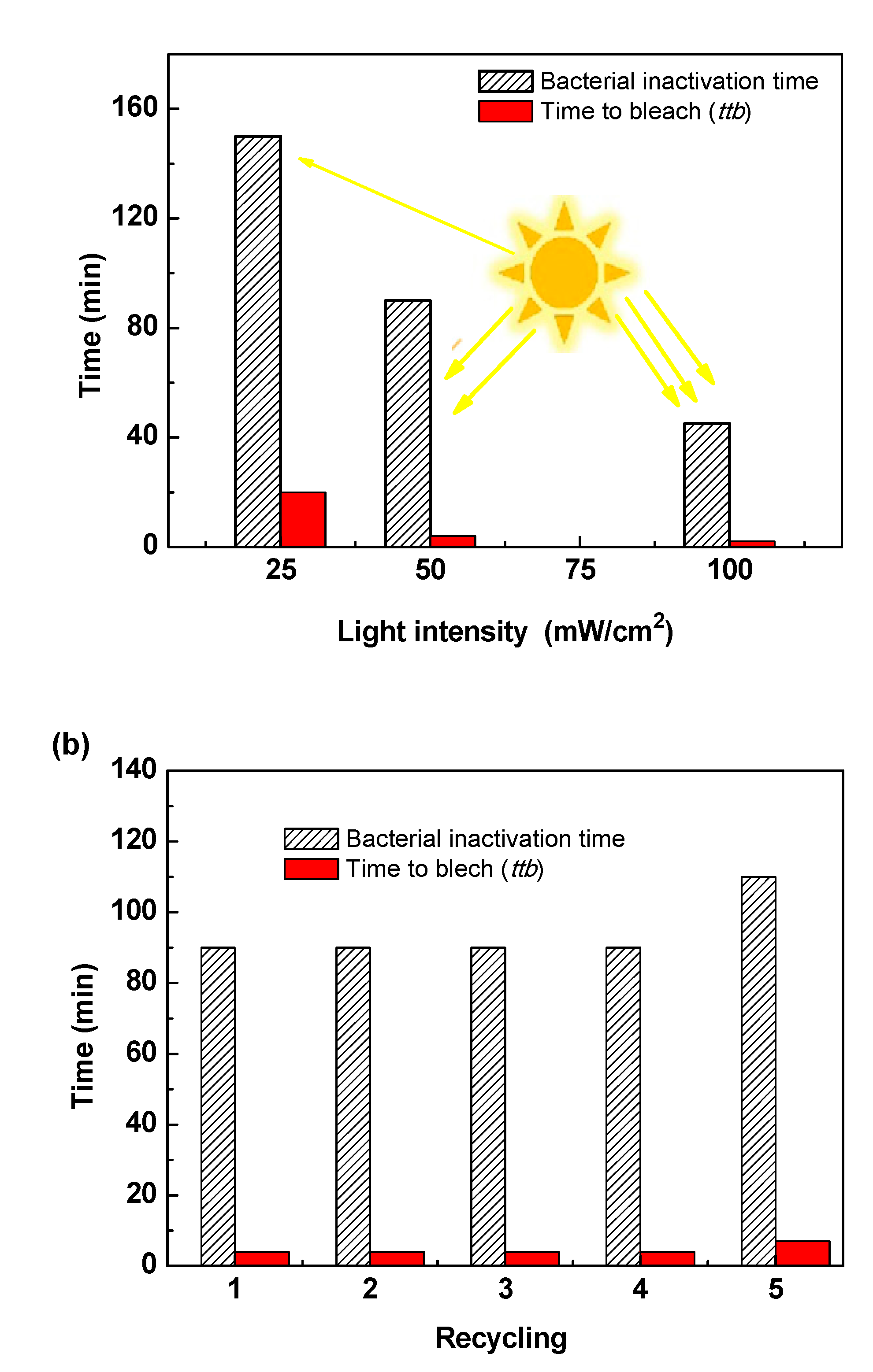

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) thin films were deposited by DC magnetron sputtering and subsequently treated in hot water at 50, 70 and 95 °C for 72h to investigate the influence of low-temperature on their structural optical and functional properties. XRD analysis revealed a progressive transformation from amorphous to anatase phase with increasing treatment temperature, accompanied by an increase in crystallite size from 5.2 to 15.1 nm. FT-IR spectroscopy confirmed enhanced surface hydroxylation, while contact-angle measurements showed a decrease from 77.4° to 19.7°, indicating a significant improvement in superior wettability. The transmittance spectroscopy revealed a slight narrowing of the optical band gap from 3.34 to 3.21 eV, consistent with improved visible-light absorption. Photocatalytic tests using the Resazurin indicator demonstrated that the film treated at 95 °C exhibited the highest activity, achieving a time to bleach of 245 s three times faster than treated at 50°C and twice as fast as treated at 70°C. Under low-intensity solar irradiation, the same sample achieved complete E. coli inactivation within 90 min. These improvements are attributed to increased crystallinity, surface hydroxyl density, and enhanced ROS generation. Overall, this study demonstrates that mild hot-water treatment is an effective, substrate-friendly route to enhance TiO₂ film wettability and multifunctional performance, enabling the fabrication of self-cleaning and antibacterial coatings on fragile materials such as plastics and textiles.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation samples and characterization methods

2.2. Photocatalyst activity and antibacterial properties

3. Results and discussion

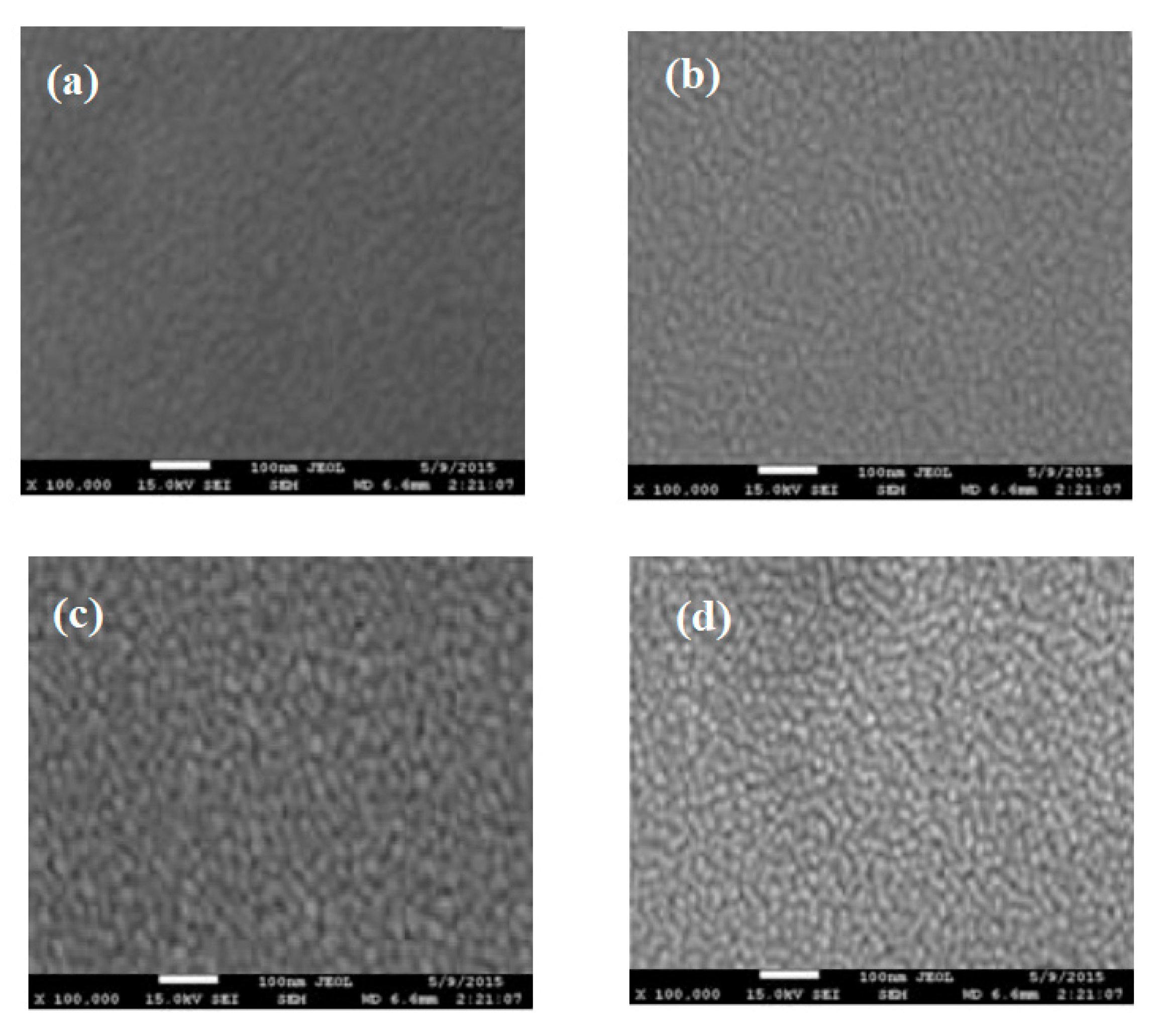

3.1. FE-SEM of Thermal Treated TiO2 Films

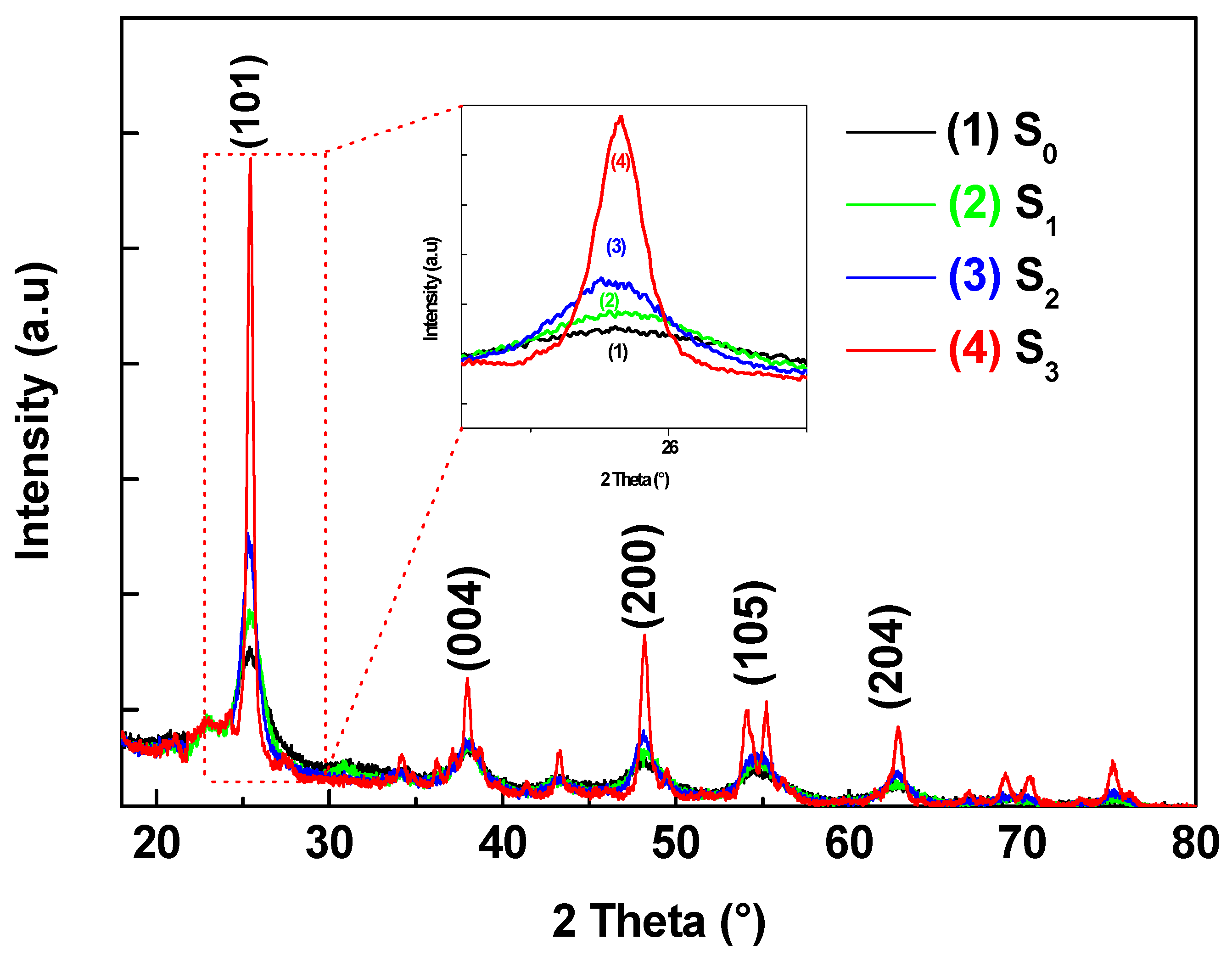

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

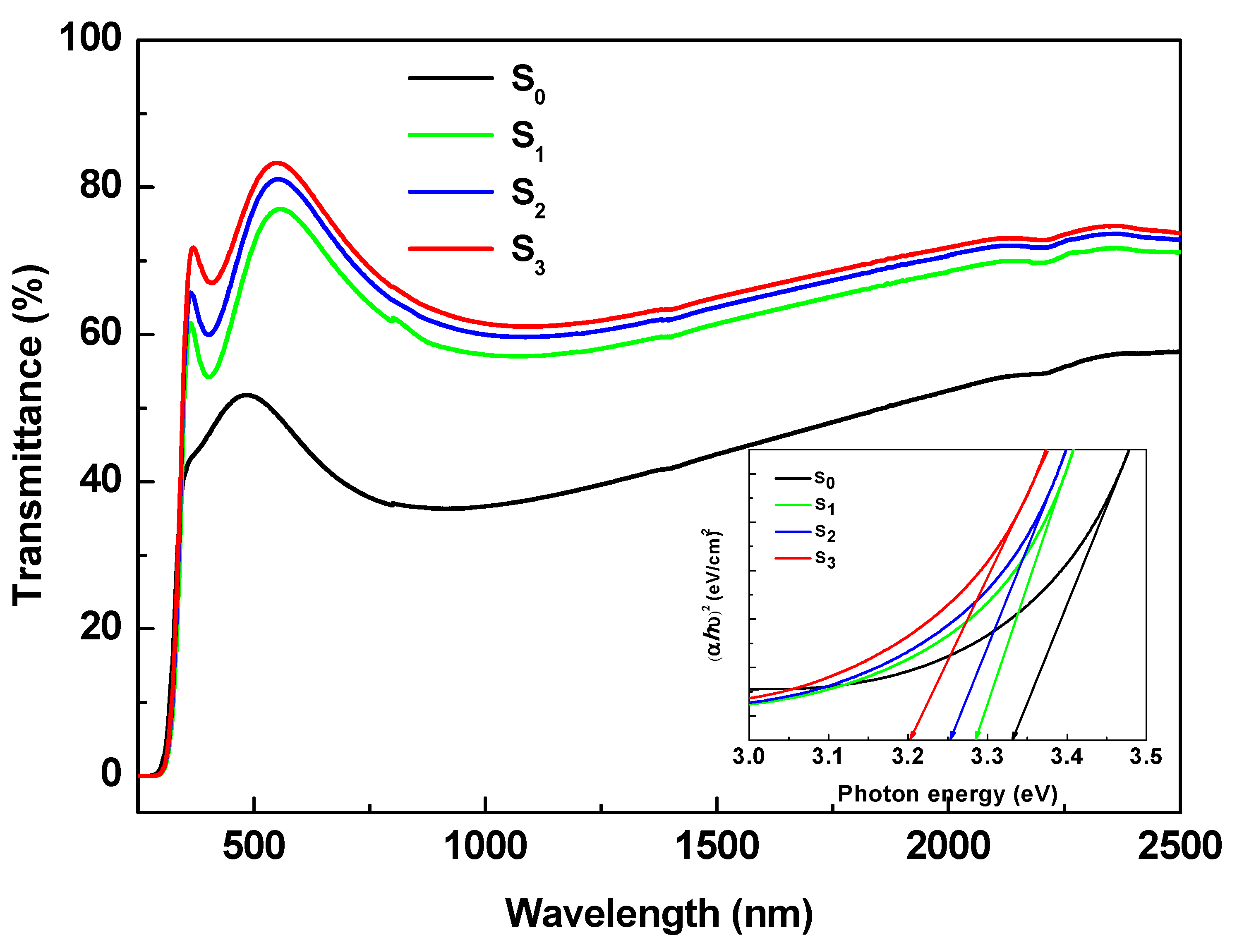

3.3. UV-vis Spectroscopy Analysis and Band gap Calculation

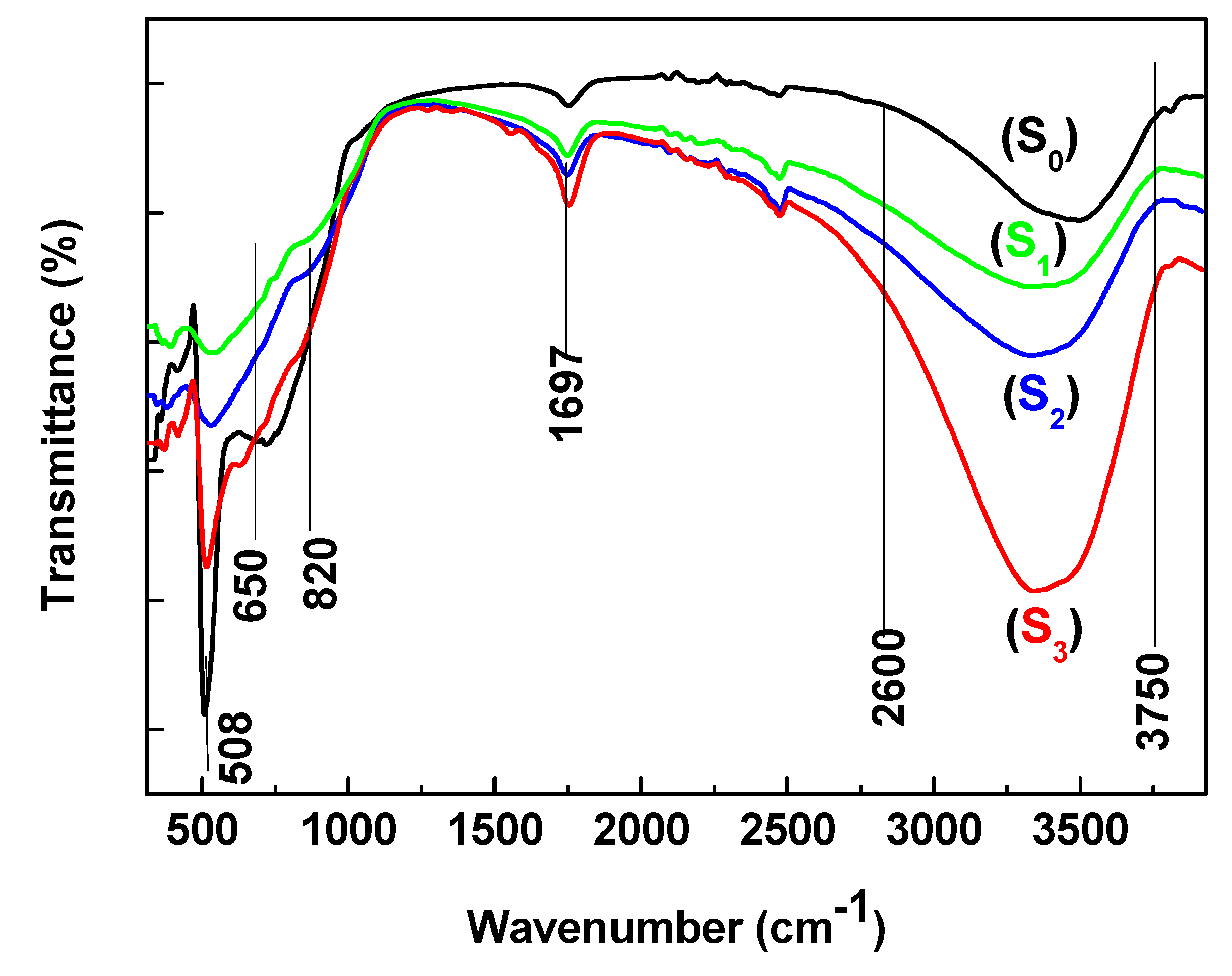

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis (FT-IR)

3.5. Contact Angle Behavior of Thermal Treated TiO₂ Films

3.6. Photocatalyst Activity and Bacterial Inactivation

4. Conclusion

References

- Mao, T.; Zha, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X. Research Progress of TiO2 Modification and Photodegradation of Organic Pollutants. Inorganics 2024, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharma, H.N.C.; Jaafar, J.; Widiastuti, N.; Matsuyama, H.; Rajabsadeh, S.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Jafri, N.N.M.; Suhaimin, N.S.; Nasir, A.M.; et al. A Review of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2)-Based Photocatalyst for Oilfield-Produced Water Treatment. Membranes 2022, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda-Marquez, J.J.; Levchuk, I.; Fernández Ibañez, P.; Sillanpää, M. A Critical Review on Application of Photocatalysis for Toxicity Reduction of Real Wastewaters. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 258, 120694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi Moud, A.; Abbasi Moud, A. Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) Liquid Crystalline State in Suspension: An Overview. Applied Biosciences 2022, 1, 244–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.; Park, M.; Park, S.-J. Recent Advances in TiO2 Films Prepared by Sol-Gel Methods for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants and Antibacterial Activities. Coatings 2019, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Pant, T.; Rohra, N.; Goyal, A.; Lawrence, M.; Dey, A.; Ganguly, P. Nanobiotechnology in Bone Tissue Engineering Applications: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Applied Biosciences 2023, 2, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustini, M.; Louis, B.; Albouy, P.A.; Kuemmel, M.; Grosso, D. Preparation of Sol−Gel Films by Dip-Coating in Extreme Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 7637–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, S.; Bouich, A.; Hajjaji, A.; Khezami, L.; Bessais, B.; Soucase, B.M. Cu-Doped TiO2 Thin Films by Spin Coating: Investigation of Structural and Optical Properties. Inorganics 2024, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chang, V.W.C.; Zhang, L.; Tse, M.S.; Tan, O.K.; Hildemann, L.M. Preparation of TiO2-Coated Polyester Fiber Filter by Spray-Coating and Its Photocatalytic Degradation of Gaseous Formaldehyde. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiflaoui, H.; Jaber, N.B.; Lazar, F.S.; Faure, J.; Larbi, A.B.C.; Benhayoune, H. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Structural and Mechanical Properties of Coatings Prepared by Electrophoretic Deposition of TiO2 Nanoparticles. Thin Solid Films 2017, 638, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zahn, D.R.T.; Madeira, T.I. Photocatalytic Performance of Sol-Gel Prepared TiO2 Thin Films Annealed at Various Temperatures. Materials 2023, 16, 5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ge-Zhang, S.; Mu, P.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Qiao, L.; Mu, H. Advances in Sol-Gel-Based Superhydrophobic Coatings for Wood: A Review. IJMS 2023, 24, 9675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiatrowski, A.; Wojcieszak, D.; Mazur, M.; Kaczmarek, D.; Domaradzki, J.; Kalisz, M.; Kijaszek, W.; Pokora, P.; Mańkowska, E.; Lubanska, A.; et al. Photocatalytic Coatings Based on TiOx for Application on Flexible Glass for Photovoltaic Panels. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 2022, 31, 6998–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Monteiro, C.S.; Silva, S.O.; Frazão, O.; Pinto, J.V.; Raposo, M.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Sério, S. Sputtering Deposition of TiO2 Thin Film Coatings for Fiber Optic Sensors. Photonics 2022, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, F.; Yang, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D. Influence of Annealing Temperature on Structure and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Thin Films Prepared by DC Reactive Magnetron Sputtering Method. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2012, 17, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, J.; Afzal, N.; Rafique, M.; Rizwan, M.; Yasin, M.W. Annealing Effect on DC Magnetron Sputtered TiO2 Film: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations. Arab J Sci Eng 2025, 50, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Kumar, V.; Kango, S.; Khilla, A.; Gupta, R. Microstructural, Wettability, and Corrosion Behaviour of TiO2 Thin Film Sputtered on Aluminium. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 2210–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, Q.; Joo, J.B.; Lu, Z.; Dahl, M.; Gan, Y.; Yin, Y. Water-Assisted Crystallization of Mesoporous Anatase TiO2 Nanospheres. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 9113–9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, K.; Carteret, C.; Lebeau, B.; Marichal, C.; Vidal, L.; Stébé, M.-J.; Blin, J.-L. Water-Catalyzed Low-Temperature Transformation from Amorphous to Semi-Crystalline Phase of Ordered Mesoporous Titania Framework. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Xiang, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Liao, Y. Review of Water-Assisted Crystallization for TiO2 Nanotubes. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, T.; Kim, K.; Hong, J. Thermoinduced and Photoinduced Sustainable Hydrophilic Surface of Sputtered-TiO2 Thin Film. Coatings 2021, 11, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghriche, O.; Rtimi, S.; Pulgarin, C.; Sanjines, R.; Kiwi, J. Effect of the Spectral Properties of TiO2, Cu, TiO2/Cu Sputtered Films on the Bacterial Inactivation under Low Intensity Actinic Light. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2013, 251, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seremak, W.; Baszczuk, A.; Jasiorski, M.; Gibas, A.; Winnicki, M. Photocatalytic Activity Enhancement of Low-Pressure Cold-Sprayed TiO2 Coatings Induced by Long-Term Water Vapor Exposure. J Therm Spray Tech 2021, 30, 1827–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Hepburn, J.; Hazafy, D.; O’Rourke, C.; Krysa, J.; Baudys, M.; Zlamal, M.; Bartkova, H.; Hill, C.E.; Winn, K.R.; et al. A Simple, Inexpensive Method for the Rapid Testing of the Photocatalytic Activity of Self-Cleaning Surfaces. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2013, 272, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Hepburn, J.; Hazafy, D.; O’Rourke, C.; Wells, N.; Krysa, J.; Baudys, M.; Zlamal, M.; Bartkova, H.; Hill, C.E.; et al. Photocatalytic Activity Indicator Inks for Probing a Wide Range of Surfaces. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2014, 290, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, I.; Rtimi, S.; Jayaprakash, A.; Van Driel, B.; Greenwood, B.; Aimable, A.; Senna, M.; Bowen, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Fluorinated Anatase Nanoparticles and Subsequent N-Doping for Efficient Visible Light Activated Photocatalysis. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, A.; Tite, T.; Ivanenko, I.; Enculescu, M.; Radu, C.; Culita, D.C.; Rostas, A.M.; Galca, A.C. TiO2 Phase Ratio’s Contribution to the Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41664–41673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaya, Y.; Souissi, R.; Toumi, M.; Madani, M.; El Mir, L.; Bouguila, N.; Alaya, S. Annealing Effect on the Physical Properties of TiO2 Thin Films Deposited by Spray Pyrolysis. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21852–21860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeribi, F.; Attaf, A.; Derbali, A.; Saidi, H.; Benmebrouk, L.; Aida, M.S.; Dahnoun, M.; Nouadji, R.; Ezzaouia, H. Dependence of the Physical Properties of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2 ) Thin Films Grown by Sol-Gel (Spin-Coating) Process on Thickness. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.H.; Kar, A.K. Titanium-Di-Oxide (TiO2) Concentration-Dependent Optical and Morphological Properties of PAni-TiO2 Nanocomposite. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2020, 105, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krengvirat, W.; Sreekantan, S.; Mohd Noor, A.-F.; Negishi, N.; Kawamura, G.; Muto, H.; Matsuda, A. Low-Temperature Crystallization of TiO2 Nanotube Arrays via Hot Water Treatment and Their Photocatalytic Properties under Visible-Light Irradiation. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2013, 137, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, A.; Szilagyi, H.; Grebenișan, E.; Sandu, A.V.; Lăzărescu, A.-V.; Romila, C. Influence of TiO2 Nanoparticles Addition on the Hydrophilicity of Cementitious Composites Surfaces. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco Navarro, L.K.; Jaroslav, C. Enhancing Photocatalytic Properties of TiO2 Photocatalyst and Heterojunctions: A Comprehensive Review of the Impact of Biphasic Systems in Aerogels and Xerogels Synthesis, Methods, and Mechanisms for Environmental Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez De La Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. IJMS 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Tomoda, R.; Nakajima, T.; Wake, H. Photoelectrochemical Sterilization of Microbial Cells by Semiconductor Powders. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1985, 29, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, P.; Roy, S.; Sarkar, S.; Mitra, S.; Pradhan, S.; Debnath, N.; Goswami, A. Damage of Lipopolysaccharides in Outer Cell Membrane and Production of ROS-Mediated Stress within Bacteria Makes Nano Zinc Oxide a Bactericidal Agent. Appl Nanosci 2015, 5, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, A.; Diez, M.S.; Rojo, D.; Bargiela, R.; Ciordia, S.; Zapico, I.; Albar, J.P.; Barbas, C.; Martins Dos Santos, V.A.P.; Fernández-García, M.; et al. Understanding the Antimicrobial Mechanism of TiO2-Based Nanocomposite Films in a Pathogenic Bacterium. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, H.A.; Ditta, I.B.; Varghese, S.; Steele, A. Photocatalytic Disinfection Using Titanium Dioxide: Spectrum and Mechanism of Antimicrobial Activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 90, 1847–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; An, T.; Li, G.; Nie, X.; Yip, H.-Y.; Zhao, H.; Wong, P.-K. Genetic Studies of the Role of Fatty Acid and Coenzyme A in Photocatalytic Inactivation of Escherichia Coli. Water Research 2012, 46, 3951–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Immersion temperature (°C) |

Lattice parameters (Å) |

Crystallite size (nm) |

|

| a =b c | |||

| 050 70 95 |

3.7291 9.8380 3.6989 9.8352 3.6985 9.8342 3.6974 9.8317 |

2,43 8.19 10.2 25.6 |

0.35 0.37 0.41 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).