1. Introduction

Soybean (

Glycine max (L.) Merrill) is one of the most important legumes in the world, valued for its high protein and fat content and its ability to biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) in symbiosis with

Bradyrhizobium japonicum [

1]. Due to its versatile use, soybean is a leader in the global agricultural economy as a major oilseed and important protein crop. Soybean has high thermal requirements, which is why it is not easy to obtain a satisfactory yield in temperate climates [

2]. However, recent years have seen an increase in interest in soybean cultivation in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, due to the need to increase domestic sources of plant protein, but also due to intensive breeding progress and progressive climate warming [

3].

Soybean productivity is highly dependent on weather conditions, especially temperature and precipitation during the growing season. The increase in average air temperature at this latitude is beneficial for thermophilic soybeans, but precipitation patterns are becoming increasingly unfavorable. As a result of climate change, many European countries, including Poland, are experiencing increasingly frequent periodic droughts, which cover large areas and cause significant losses in agricultural production [

4]. Soil water deficiency disrupts physiological and metabolic processes, leading to reduced plant growth, decreased stomatal conductance, inhibited photosynthesis, accelerated leaf ageing and, consequently, affects crop yield and quality [

5,

6].

The reduction in soybean productivity under drought conditions depends on the duration and intensity of stress and the phenological stage of the plants. Soybeans are particularly sensitive to water deficit during the generative phase, i.e., during flowering, pod setting and seed filling. This is a critical period associated with increased water demand by plants, therefore water shortage during this period can cause a significant reduction in seed yield [

7,

8]. Limited soil moisture also reduces the activity of

Bradyrhizobium japonicum symbiotic bacteria and the efficiency of biological nitrogen fixation, leading to physiological disturbances, deterioration in the efficiency of assimilate utilization and, consequently, a reduction in seed yield [

7,

9,

10,

11].

Nitrogen fertilization is one of the most important agrotechnical factors determining plant growth and yield. Nitrogen plays a key role in growth processes, protein, chlorophyll and enzyme synthesis, and its availability determines the efficiency of photosynthesis and biomass production, thus having a decisive impact on both yield and quality [

12,

13,

14]. Soybeans assimilate large amounts of nitrogen, both in the vegetative and generative phases, and the total amount of N taken up is closely correlated with seed yield. Soybeans require approximately 70-90 kg of N per ton of seed [

15]. It meets its nitrogen requirements using biologically fixed nitrogen as well as nitrogen originating from the soil and from mineral fertilizers. With abundant nodulation, symbiotic bacteria can fix up to 100 kg N ha

-¹, which can cover up to 60% of the plants’ demand for this element [

16]. The remainder should be supplemented with mineral nitrogen, whereby the application of an appropriate rate is crucial to maintain a balance between growth and the efficiency of BNF. Optimal rates of mineral nitrogen can stimulate early soybean development, increase leaf area, chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity. However, excessive nitrogen fertilizations can lead to reduced nodule activity, decreased symbiosis efficiency, as well as disturbances in assimilate metabolism and accelerated leaf ageing [

17].

An important factor in production that improves the technological and utility value of plants is breeding progress. New cultivars are generally characterized by higher yields, better quality traits and greater resistance to environmental stresses. Genetic diversity between cultivars determines their ability to adapt to specific environmental conditions, the efficiency of water and nutrient use, including nitrogen, and resistance to abiotic stresses. Cultivars also differ in growth dynamics, length of the growing season, plant architecture, and photosynthesis intensity, which can affect plant productivity and morphological and physiological parameters such as plant height, LAI index, chlorophyll content in leaves and PSII efficiency [

18].

Understanding the interaction between genetic factors, nitrogen fertilization and weather conditions is crucial for optimizing the yield and physiological efficiency of soybeans in temperate climates. The aim of the study was to determine the effect of cultivar and nitrogen fertilization rate on selected morphological and physiological traits and seed yield of soybeans grown under field conditions in central-eastern Poland.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Treatment Specifications

A strict two-year field experiment was conducted at the Experimental and Implementation Field of the Lublin Agricultural Advisory Centre in Końskowola (Lubelskie voivodeship, 51°24′33″N 22°03′06″E). The experiment was established on loamy soil formed from loess, with a soil pH (KCl) ranging from 6.9 to 7.4. The content of available macronutrients ranged from (mg 100g-1 of soil): P – 9.0-19.2; K – 8.6-18.7; Mg – 10.3-11.5. The organic carbon content was 0.96-0.97%.

A two-factor experiment was set up in a split-plot design, with four replicates, on plots with an area of 30 m². The research factors were: nitrogen rate: 0 (control treatment N0), 30 kg ha-¹ (moderate rate N30), 60 kg ha-¹ (high rate N60) and common soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) cultivars: ‘Abelina’ (medium early), ‘Coraline’ (very late), ‘Malaga’ (very late), ‘Petrina’ (very late).

During phosphorus and potassium fertilization, the natural soil fertility was taken into account, using pre-sowing (kg ha⁻¹): P – 17.4, K – 46.5 calculated as pure component. Nitrogen fertilization corresponded to rates of 30 and 60 kg ha-¹, with a rate of 30 kg ha-¹ applied pre-sowing, and a rate of 60 kg divided into two parts, with 50% applied pre-sowing and 50% top-dressing at BBCH 61. No nitrogen was sown on the control object. Before sowing, the soybean seeds were treated with a seed dressing and inoculated with Nitragina containing Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteria, and sown at a rate of 70 seeds per 1 m². All agrotechnical treatments were performed on time, in accordance with the applicable recommendations for soybeans.

2.2. Agronomic and Physiological Traits

During the growing season, four developmental stages of soybean (BBCH 61, 65, 70, 77) were measured for chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm, PI), leaf area index (LAI) and leaf greenness index (SPAD). Direct chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were performed using a PocketPEA fluorometer (Hansatech Instruments – WB). The Fv/Fm index, which determines the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII), and the PI index, which describes PSII performance index, were evaluated. Chlorophyll fluorescence indices are used to determine the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and to assess the physiological condition of plants. The measurements were taken after 20 minutes of leaf adaptation in the dark, and the result from each plot was the average of 10 measurements.

LAI (leaf area index) measurements were performed using the LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyser (LI-COR). It determines the ratio of the total one-sided area of all leaves to the area of the substrate above which they are located. The result from each plot was the average of 3 measurements.

Leaf greenness index (SPAD) measurements were performed using a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Minolta). The device measures the transmission of light beams passing through the leaf, of which only red light is absorbed by the chlorophyll in the leaves. The device measures the differences between light absorption by the leaf at wavelengths of 650 and 950 nm, and the quotient of these differences is the leaf greenness index or relative chlorophyll content. The value of the reading is proportional to the chlorophyll content in the tested area (6 mm²) of the leaf. The result from each plot was the average of 30 measurements.

Before harvesting, 10 plants were randomly selected from each plot to determine the biometric characteristics of the plants: plant height (cm), number of pods per plant (pcs), number of seeds per plant (pcs), seed weight per plant (g). At the stage of full maturity, the seed yield (t ha-¹) at 14% moisture content and the thousand seed weight (TSW) (g) were determined.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The collected research results were statistically analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a three-factor system, in which the factors were: soybean cultivar, nitrogen fertilization rate and year of research. To compare the differences between the means for the main factors and interactions, Tukey’s multiple range test (HSD) was used at a significance level of p≤0.05. The calculations were performed using Statgraphics Centurion XVI software. In addition, Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were calculated between selected morphological, yield-related and physiological traits in order to determine the relationships between the analyzed parameters.

2.4. Weather Conditions

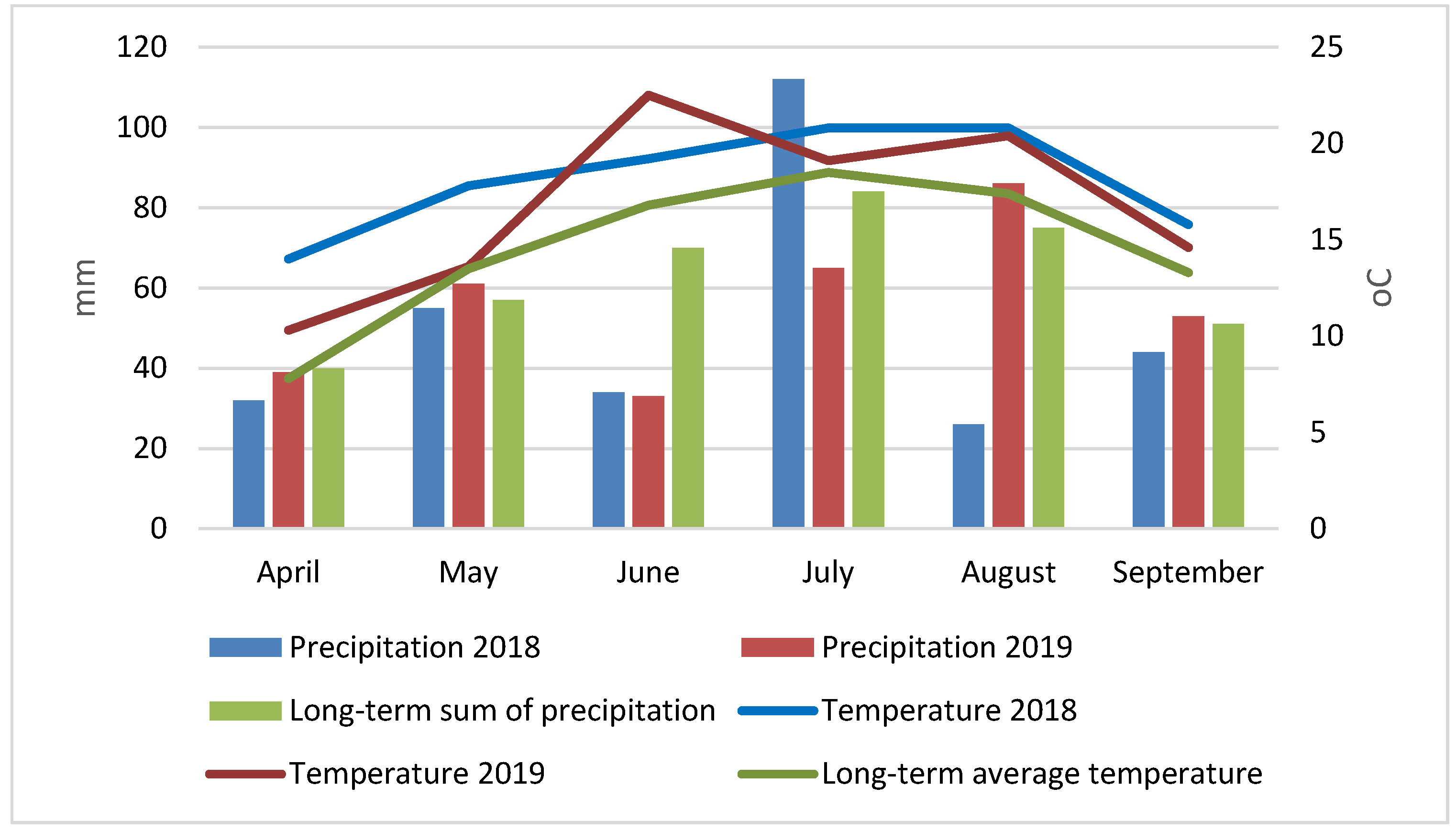

Weather conditions varied between the two growing seasons (

Figure 1). Analysis of thermal conditions showed that these years were exceptionally warm, with the average monthly air temperature in all months and years of the study being higher than the long-term average. In the first growing season (2018), April, May and August were particularly warm (temperatures higher by 6.2, 4.3 and 3.4

oC) higher than the long-term average, while in the second (2019) – June and August (temperatures 5.7 and 3.0

o C higher, respectively) compared to the long-term averages.

The total precipitation for the entire growing season (April-September) was lower in both the first and second years of the study, by 20 and 11%, respectively, compared to the long-term average. In the first growing season, significant rainfall deficits were recorded in April, June and August, 20, 51 and 65% lower than the long-term average, respectively. In July, however, rainfall was 33% higher than average. In the second season, the greatest rainfall deficits were recorded in June and July, 53 and 23% lower than the long-term average, respectively, while August saw a 15% increase in rainfall.

Hydrothermal conditions were also described using the Sielianinov hydrothermal index (k) [

19], calculated using the following formula:

where:

P - monthly sum of precipitation (mm),

Ʃ t - sum of average daily temperatures in a given month > 0 °C.

Table 1.

Characteristics of growing seasons based on the Sielaninow hydrothermal index (k).

Table 1.

Characteristics of growing seasons based on the Sielaninow hydrothermal index (k).

| Month |

2018 |

k (2018) |

2019 |

k (2019) |

April

May

June

July

August

September |

dry

fairly dry

very dry

moderately wet

very dry

fairly dry |

0.71

1.08

0.65

1.87

0.43

1.03 |

fairly dry

optimal

very dry

fairly dry

optimal

optimal |

1.30

1.60

0.54

1.17

1.49

1.33 |

4. Discussion

The success of soybean cultivation in Poland depends on many factors, but one of the most important is the weather conditions during the growing season [

8,

20]. During the years of research, plant growth and development were shaped by variable temperature and humidity conditions, which was reflected in the diversity of morphological and physiological traits and the level of soybean yield. The first year of the study was characterized by a high average air temperature during the growing season (18.1 °C) and low total precipitation (303 mm), which indicates water stress during the vegetative phase and the beginning of soybean flowering (May-June) and pod filling (August-September) (

Table 1). In the second year of the study, the average air temperature during the growing season (16.8 °C) was higher than the long-term average (14.6 °C), and the total precipitation (337 mm) was below the long-term average (377 mm), but the distribution of precipitation was more even. The greatest water shortages occurred during the critical phase of soybean flowering and pod setting (June-July).

Soybean yields were significantly higher in the first year (by an average of 12.7%) compared to the second year. Soybeans have moderate water requirements and tolerate short periods of drought quite well, as they are genetically adapted to this. It develops a strong root system, pubescence on leaves and stems to reduce transpiration, and we also observe the phenomenon of heliotropism, which involves the vertical positioning of leaves in conditions of high temperatures and water shortages, limiting leaf heating and excessive transpiration. This is confirmed by the research of Tabrizi et al. [

21], which showed that reducing soybean irrigation by 25% compared to optimally irrigated controls allowed yields to be maintained at a stable level of around 90%.

The reduction in soybean productivity due to soil water deficiency depends on the duration and severity of the drought and the phenological stage of the plants [

6,

22,

23]. Soybeans do not tolerate prolonged water shortages during critical periods, especially during flowering and pod set [

7]. Lack of moisture during this period causes the rejection of flowers and young pods and results in a lower number of pods and seeds set [

24,

25]. This is confirmed by the studies of Eck et al. [

26] which showed that prolonged stress imposed on plants from the beginning of flowering to the end of pod development reduced soybean seed yield more (by 45%) compared to stress in earlier stages of development. A smaller reduction in yield was also recorded when the stress was short-term and occurred between the beginning and full flowering and the beginning of pod development (by 9-13%). In addition, drought in the summer months, combined with high temperatures, leads to faster soybean maturation and a shorter flowering and pod filling phase [

27]. In our own studies, the first growing season was more deficient in terms of rainfall, but the dry periods occurred mainly at the beginning (June) and end of the growing season (August-September), while the critical period, which falls during flowering and pod setting (July), was moderately humid, which allowed for the formation of a larger number of pods and a significantly higher seed yield (average 4.80 t ha

-¹) compared to the yield in the second season (4.26 t ha

-¹). On the other hand, water shortages during the vegetative phases of soybean contributed to a significant reduction in plant height (by 5.3% on average), a reduction in leaf area index (by 29.1% on average), relative chlorophyll content in leaves (by 24.7% on average) and a reduction in photosynthetic activity expressed by chlorophyll fluorescence indices Fv/Fm and PI (by 9.5 and 58.2%, respectively). In turn, low rainfall at the end of the growing season resulted in a significantly lower TSW (by 5.3% on average). Higher values describing these parameters were obtained in the second year of the study, when air temperatures were lower and rainfall distribution during the growing season was more even. The reduction in morphological and physiological parameters under drought conditions is associated with a decrease in the intensity and disruption of the photosynthesis process, which in turn weakens biomass accumulation and its transfer to seeds. This is confirmed by the results of studies by various authors [

6,

7,

25,

27].

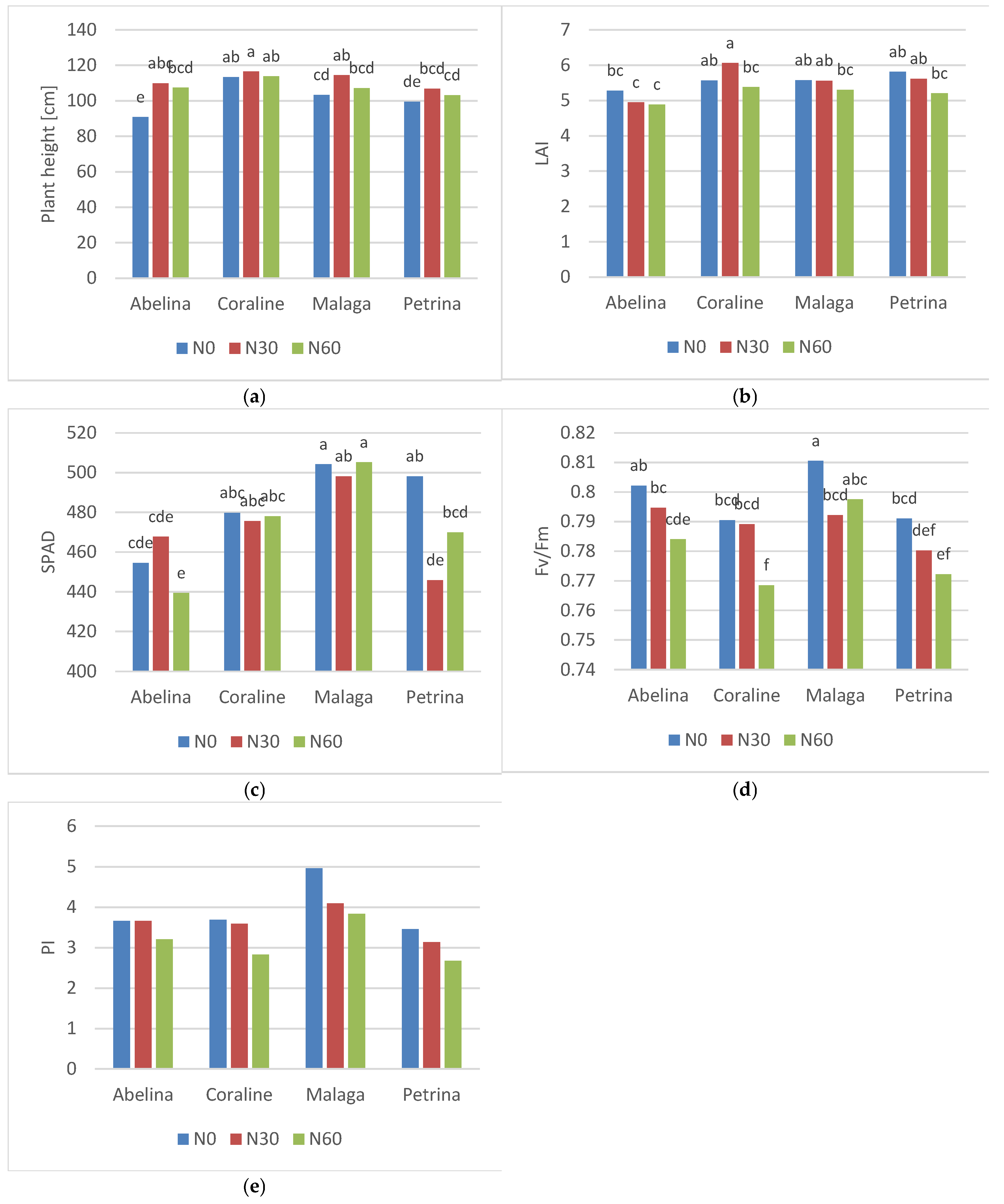

One of the main factors determining the growth, development and yield of soybeans is the genotype [

28,

29]. The results of our own research showed, that the soybean cultivars studied differed significantly in terms of the analyzed traits. The very late cultivar ‘Coraline’ stood out with the highest height, while the highest physiological parameters (SPAD index, Fv/Fm and PI indices) were found in the very late ‘Malaga’, which may indicate its greater adaptability to stressful conditions associated with soil water deficiencies. The high values of physiological parameters translated into good productivity of the ‘Malaga’ cultivar, whose average seed yield (5.06 t ha

-¹) was significantly higher than that of the other cultivars, on average by 14.5-19.0% depending on the cultivar. In addition, ‘Malaga’ was characterized by seeds with the highest TSW (230 g). Among the cultivars tested, the medium-early ‘Abelina’ had the lowest yield, as well as was the shortest in height and showed the lowest SPAD and LAI indices.

The genetic potential of soybean cultivars largely depends on their earliness class. Cultivars with a long growing season generally yield better than earlier cultivars because they have more time to grow and develop assimilation organs and produce a yield. This contributes to the development of a larger leaf area and longer photosynthetic activity, which affects biomass growth and seed yield. This is confirmed by the results of our own research, as well as earlier by the authors’ previous studies. Staniak et al. [

30] showed that among the 15 genotypes studied, late and very late cultivars yielded on average 22.5% more, and medium-early cultivars 20.0% more than early and very early cultivars. Significant differences were also found within individual groups of cultivars. This is confirmed by the research of Prusiński et al. [

31], which showed that the very early cultivar ‘Annushka’ had a significantly higher seed yield, plant height, lowest pod height and thousand seed weight compared to the early ‘Aldana’.

Nitrogen fertilization had a significant effect on plant growth, physiological parameters and, consequently, seed yield and its structural elements. Soybeans fertilized with rates of 30 and 60 kg N ha⁻¹ were significantly taller and had a higher SPAD index compared to the control treatment, which confirms the positive effect of nitrogen on chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthetic activity. At the same time, a decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Fv/Fm and PI) was observed after the application of higher N rates (N60), which may indicate a decrease in the efficiency of PSII functioning with greater availability of mineral nitrogen. For most plants, the Fv/Fm parameter is considered the most sensitive indicator for determining the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus, although it is highly dependent on environmental factors [

32]. According to Kaschuk et al. [

17], soybeans using nitrogen bound as a result of symbiosis with

Bradyrhizobium japonicum show higher photosynthetic activity and slower leaf ageing compared to plants fertilized with mineral nitrogen. The use of higher nitrogen rates in our own studies (N60) may therefore indicate a reduction in PSII activity due to a decrease in the role of BNF. These results confirm, that excessive mineral nitrogen fertilization, despite its positive effect on plant growth and leaf greenness index (SPAD), may not be conducive to maintaining high photosynthetic activity, especially in later stages of development. In contrast, moderate fertilization (N30) improved the physiological condition of plants (high SPAD values) without a significant decrease in PSII efficiency, indicating a more balanced use of mineral and symbiotic nitrogen.

The effect of nitrogen was also evident in the formation of yield components. The application of a higher rate of nitrogen (N60) significantly increased the number of pods per plant and the number and weight of seeds, but did not result in a proportional increase in yield. This was probably due to a reduction in the TSW, which was significantly higher in the control object (N0) and with moderate fertilization (N30). This phenomenon may indicate compensation between the elements of the yield structure, as the increase in the number of seeds was at the expense of their unit weight. Similar relationships were observed by other authors [

33], who found that moderate nitrogen fertilizations (30 kg N ha

-1) improved the vegetative parameters of soybeans without significantly increasing seed yield. The results obtained indicate, that moderate nitrogen fertilization (N30) is more beneficial for maintaining the balance between vegetative growth and soybean productivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and E.B.; methodology, E.B.; investigation, E.B., K.C., A.S; resources, M.S..; data curation, E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., E.B., K.C., A.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, M.S.; funding acquisition, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Average monthly air temperature and monthly sum of precipitation in 2018-2019, taking into account the long-term average (1871-2000).

Figure 1.

Average monthly air temperature and monthly sum of precipitation in 2018-2019, taking into account the long-term average (1871-2000).

Figure 2.

Effects of the cultivar and nitrogen rate on: (a) the plant height, (b) leaf area index (LAI), (c) leaf greenness index (SPAD), (d) maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), (e) PSII performance index (PI). Means followed by different letters are significantly different. The level of significance p≤0.05 (HSD, Tukey test).

Figure 2.

Effects of the cultivar and nitrogen rate on: (a) the plant height, (b) leaf area index (LAI), (c) leaf greenness index (SPAD), (d) maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), (e) PSII performance index (PI). Means followed by different letters are significantly different. The level of significance p≤0.05 (HSD, Tukey test).

Figure 3.

Effects of the cultivar and nitrogen rate on: (a) seed yield, (b) thousand seed weight (TSW), (c) number of pods, (d) number of seeds, (e) weight of seeds; Means followed by different letters are significantly different. The level of significance p≤0.05 (HSD, Tukey test).

Figure 3.

Effects of the cultivar and nitrogen rate on: (a) seed yield, (b) thousand seed weight (TSW), (c) number of pods, (d) number of seeds, (e) weight of seeds; Means followed by different letters are significantly different. The level of significance p≤0.05 (HSD, Tukey test).

Table 2.

Effects of the variety, nitrogen rate and year on the plant height (PH), leaf area index (LAI), leaf greenness index (SPAD) and chlorophyll fluorescence indices: Fv/Fm – maximum quantum efficiency of PSII and PI – PSII performance index.

Table 2.

Effects of the variety, nitrogen rate and year on the plant height (PH), leaf area index (LAI), leaf greenness index (SPAD) and chlorophyll fluorescence indices: Fv/Fm – maximum quantum efficiency of PSII and PI – PSII performance index.

| Factor |

Source

of variation |

PH (cm) |

LAI |

SPAD |

Fv/Fm |

PI |

| Variety (V) |

Abelina

Malaga

Coraline

Petrina

p-value |

102.7 c

108.3 b

114.5 a

103.2 c

*** |

5.04 b

5.48 a

5.67 a

5.54 a

*** |

453.9 c

502.4 a

477.8 b

471.3 b

*** |

0.794 b

0.800 a

0.783 c

0.781 c

*** |

3.507 b

4.296 a

3.369 bc

3.136 c

*** |

| Fertilization (F) |

N0

N30

N60

p-value |

101.8 c

111.9 a

107.9 b

*** |

5.56 a

5.55 a

5.19 b

*** |

484.1 a

471.8 b

473.2 b

** |

0.799 a

0.789 b

0.781 c

*** |

3.940 a

3.620 a

3.136 b

*** |

| Year (Y) |

2018

2019

p-value |

104.3 b

110.1 a

*** |

4.51 b

6.36 a

*** |

409.2 b

543.5 a

*** |

0.750 b

0.829 a

*** |

2.101 b

5.030 a

*** |

V x F

V x Y

F x Y

V x F x Y |

p-value

p-value

p-value

p-value |

***

***

ns

ns |

*

ns

ns

ns |

***

***

**

*** |

**

***

***

*** |

ns

***

*

ns |

Table 3.

Plant height (PH) and leaf area index (LAI) of soybean in 2018-2019.

Table 3.

Plant height (PH) and leaf area index (LAI) of soybean in 2018-2019.

| Treatment |

PH (cm) |

LAI |

| |

2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

| Abelina |

102.6 c

|

102.9 bc

|

4.00 |

6.07 |

| Coraline |

114.9 a

|

114.1 a

|

4.81 |

6.53 |

| Malaga |

102.9 bc

|

113.7 a

|

4.55 |

6.41 |

| Petrina |

96.8 c

|

109.6 ab

|

4.67 |

6.42 |

|

p-value |

*** |

ns |

| N0 |

99.3 |

104.2 |

4.72 |

6.40 |

| N30 |

108.1 |

115.7 |

4.58 |

6.51 |

| N60 |

105.4 |

110.4 |

4.22 |

6.17 |

|

p-value |

ns |

ns |

Table 4.

Leaf greenness index (SPAD) and chlorophyll fluorescence indices: Fv/Fm – maximum quantum efficiency of PSII and PI – PSII performance index, in 2018-2019.

Table 4.

Leaf greenness index (SPAD) and chlorophyll fluorescence indices: Fv/Fm – maximum quantum efficiency of PSII and PI – PSII performance index, in 2018-2019.

| Treatment |

SPAD |

Fv/Fm |

PI |

| 2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

| Abelina |

372.1 e

|

535.6 ab

|

0.761 b

|

0.827 a

|

1.794 cd

|

5.220 a

|

| Coraline |

424.2 d

|

531.3 b

|

0.735 c

|

0.830 a

|

2.001 c

|

4.737 a

|

| Malaga |

455.1 c

|

549.8 ab

|

0.768 b

|

0.832 a

|

3.287 b

|

5.306 a

|

| Petrina |

385.3 e

|

557.3 a

|

0.735 c

|

0.828 a

|

1.322 d

|

4.857 a

|

| p-value |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| N0 |

422.2 b

|

546.0 a

|

0.764 c

|

0.833 a

|

2.570 c

|

5.311 a

|

| N30 |

395.6 c

|

548.0 a

|

0.744 d

|

0.835 a

|

1.942 d

|

5.297 a

|

| N60 |

409.7 bc

|

536.5 a

|

0.741 d

|

0.820 b

|

1.791 d

|

4.482 b

|

| p-value |

** |

*** |

** |

Table 5.

Effects of the cultivar, nitrogen rate and year on seed yield, thousand seeds weight (TSW) and yield structure of soybean by three-way ANOVA.

Table 5.

Effects of the cultivar, nitrogen rate and year on seed yield, thousand seeds weight (TSW) and yield structure of soybean by three-way ANOVA.

| Factor |

Source

of variation |

Number of pods per plant |

Number of seeds per plant |

Weight of seeds per plant (g) |

Seed yield

(t ha-1) |

TSW

(g) |

| Variety (V) |

Abelina

Malaga

Coraline

Petrina

p-value |

28.3 b

38.3 a

30.3 b

37.5 a

*** |

50.4 b

78.5 a

56.8 b

69.7 a

*** |

9.01 b

14.2 a

13.6 a

14.0 a

*** |

4.25 c

4.42 b

5.06 a

4.39 bc

*** |

169.7 c

186.5 b

229.8 a

190.5 b

*** |

| Fertilization (F) |

N0

N30

N60

p-value |

32.6 b

30.8 b

37.4 a

*** |

62.3 b

58.1 b

71.2 a

*** |

12.4 b

11.5 b

14.2 a

** |

4.17 b

4.65 a

4.77 a

*** |

197.2 a

199.9 a

185.3 b

*** |

| Year (Y) |

2018

2019

p-value |

35.2 a

32.0 b

* |

66.8 a

60.9 b

* |

12.9 a

12.5 a

ns |

4.80 a

4.26 b

*** |

188.9 b

199.4 a

*** |

V x F

V x Y

F x Y

V x F x Y |

p-value

p-value

p-value

p-value |

***

***

*

** |

***

***

**

** |

***

**

*

ns |

***

***

***

*** |

ns

***

ns

** |

Table 6.

Seed yield and thousand seeds weight (TSW) of soybean in 2018-2019.

Table 6.

Seed yield and thousand seeds weight (TSW) of soybean in 2018-2019.

| Treatment |

Yield of seeds (t ha-1) |

TSW (g) |

| |

2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

| Abelina |

4.29 cd

|

4.21 cd

|

177.6 c

|

161.4 d

|

| Coraline |

4.80 b

|

4.05 d

|

170.5 c

|

202.4 b

|

| Malaga |

5.71 a

|

4.40 c

|

230.6 a

|

229.1 a

|

| Petrina |

4.40 c

|

4.39 c

|

176.9 c

|

204.1 b

|

|

p-value |

*** |

*** |

| N0 |

4.11 b

|

4.23 b

|

192.2 |

202.2 |

| N30 |

5.06 a

|

4.24 b

|

195.9 |

204.0 |

| N60 |

5.23 a

|

4.31 b

|

178.6 |

192.0 |

|

p-value |

*** |

ns |

Table 7.

Yield structure of soybean in 2018-2019.

Table 7.

Yield structure of soybean in 2018-2019.

| Treatment |

Number of pods per plant |

Number of seeds per plant |

Weight of seeds per plant (g) |

| 2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

2019 |

| Abelina |

28.1 c

|

28.5 c

|

50.2 c

|

50.6 c

|

9.0 b

|

9.0 b

|

| Coraline |

44.5 a

|

32.1 bc

|

92.8 a

|

64.2 bc

|

15.5 a

|

12.9 a

|

| Malaga |

32.9 bc

|

27.8 c

|

61.8 bc

|

51.9 c

|

14.8 a

|

12.3 ab

|

| Petrina |

35.4 bc

|

39.6 ab

|

62.5 bc

|

77.0 ab

|

12.3 ab

|

15.6 a

|

| p-value |

*** |

*** |

** |

| N0 |

32.2 b

|

33.1 b

|

60.6 b

|

64.0 b

|

11.7 b

|

13.1 ab

|

| N30 |

32.0 b

|

29.5 b

|

59.4 b

|

56.8 b

|

11.5 b

|

11.5 b

|

| N60 |

41.5 a

|

33.4 b

|

80.5 a

|

61.9 b

|

15.5 a

|

12.8 ab

|

| p-value |

* |

* |

* |

Table 8.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) among the analyzed traits of soybean (n = 48).

Table 8.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) among the analyzed traits of soybean (n = 48).

| Variable |

PH |

NP |

NS |

SW |

TSW |

LAI |

Fv/Fm |

PI |

SPAD |

| SY |

0.11 |

0.17 |

0.19 |

0.31* |

0.31* |

-0.30* |

-0.27 |

-0.07 |

-0.003 |

| PH |

— |

0.09 |

0.20 |

0.19 |

0.06 |

0.21 |

0.05 |

0.10 |

0.23 |

| NP |

— |

— |

0.97*** |

0.90*** |

-0.23 |

-0.01 |

-0.24 |

-0.13 |

0.13 |

| NS |

— |

— |

— |

0.89*** |

-0.22 |

-0.01 |

-0.24 |

-0.12 |

0.14 |

| SW |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.11 |

0.06 |

-0.07 |

0.05 |

0.28 |

| TSW |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.28 |

0.42** |

0.48** |

0.39** |

| LAI |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.75*** |

0.77*** |

0.80*** |