Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

References

- Abo Sedera, F. A.; Abd El-Latif, A. A.; Bader, L. A. A.; Rezk, S. M. Effect of NPK mineral fertilizer levels and foliar application with humic and amino acids on yield and quality of strawberry. Egyptian Journal of Applied Science 2010, 25, 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Alhasawi, A.; Castonguay, Z.; Appanna, N. D.; Auger, C.; Appanna, V. D. Glycine metabolism and anti-oxidative defence mechanisms in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Microbiological research 2015, 171, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvares, C. A.; Stape, J. L.; Sentelhas, P. C.; Gonçalves, J. D. M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 22(6), 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, R.; Galili, G.; Cohen, H. The metabolic roles of free amino acids during seed development. Plant Science 2018, 275, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Arginine increases tolerance to nitrogen deficiency in Malus hupehensis via alterations in photosynthetic capacity and amino acids metabolism. Frontiers in plant science 2022, 12, 772086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, C. S.; de Almeida, T. L.; Camara, A. M.; Prates, J. F.; Panozzo, L. E. Growth of wheat plants from high and low vigor seeds treated with amino acids. journal of Engineering in Agriculture 2019, 27(5), 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. F. Sisvar: a Guide for its Bootstrap procedures in multiple comparisons. Ciência e agrotecnologia 2014, 38, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gins, M. S.; Gins, V. K.; Baikov, A. A.; Kononkov, P. F.; Pivovarov, V. F.; Sidelnikov, N. I.; Goncharova, O. I. Antioxidant content and growth at the initial ontogenesis stages of Passiflora incarnata plants under the influence of biostimulant Albit. Russian agricultural sciences 2017, 43(5), 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluhić, D. Primjena biostimulatora na bazi aminokiselina u poljoprivrednoj proizvodnji. Glasnik Zaštite Bilja 2020, 43(3.), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S. A.; Ali, O. A. Physiological and biochemical studies on drought tolerance of wheat plants by application of amino acids and yeast extract. Annals of Agricultural Sciences 2014, 59(1), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, W.; Geiger, R. Klimate der Erde; Verlagcondicionadas: Gotha, 1928; Justus Perthes. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Q.; Chen, H. Y.; Ni, Q. X.; Kyu, S. L. Evaluation of the role of mixed amino acids in nitrate uptake and assimilation in leafy radish by using 15N-labeled nitrate. Agricultural Sciences in China 2008, 7(10), 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavolta, E.; Vitti, G. C.; Oliveira, S. A. D. Evaluation of the nutritional status of plants: principles and applications, 2nd ed.; Brazilian Association for Potash and Phosphate Research: Piracicaba, 1997; p. 319 p. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, M. F.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Tanaka, H.; Asao, T. Effects of amino acids on the growth and flowering of Eustoma grandiflorum under autotoxicity in closed hydroponic culture. Scientia Horticulturae 2015, 192, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, R.; Umar, S.; Khan, N. A. Exogenous salicylic acid improves photosynthesis and growth through increase in ascorbate-glutathione metabolism and S assimilation in mustard under salt stress. Plant signaling & behavior 2015, 10(3), e1003751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T. O.; Santos, R. F.; Santos, N. B.; Zitha, A. R.; Tokura, L. K. Use of zinc and silver nanoparticles associated with amino acids in soybean seeds. Caribbean Journal of Social Sciences 2024, 13(5), e3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Costa, L. F. Dos.; Melo Ferreira, E. de.; Junqueira, P. H.; Lobo, L. M.; Muniz, C. O.; dos Santos Isepon, J. Physical and chemical characteristics and productivity of 'Pera 'orange as a function of foliar application of amino acids. Revista Trópica: Agricultural and Biological Sciences 10(1), 53–62.

- Santos, H. G. dos.; Jacomine, P. K. T.; Anjos, L. H. C. dos.; Oliveira, V. A. de.; Lumbreras, J. F.; Coelho, M. R.; Cunha, T. J. FBrazilian Soil Classification System, 5th ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, 2018; p. 355p. [Google Scholar]

- Sh Sadak, M.; Abdelhamid, M. T.; Schmidhalter, U. Effect of foliar application of aminoacids on plant yield and some physiological parameters in bean plants irrigated with seawater. Acta biológica colombiana 2015, 20(1), 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, R. D. Effect of seed pre-treatment with varying concentrations of salicylic acid on antioxidant response of wheat seedlings. Indian journal of plant physiology 2014, 19(3), 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D. M. G.; Lobato, E. (Eds.) Cerrado: Soil Correction and Fertilization, 2. ed.; Embrapa Technological Information/Embrapa-CPA: Brasília, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, N. T.; dos Santos, N. M. C.; Jesus, A. S.; de Oliveira, F. C. Commercial formulation containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and supplemented with amino acids via foliar application in coffee plants. Foco Journal 2022, 15(5), e525–e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, W. F.; Fagan, E. B.; Soares, L. H.; Umburanas, R. C.; Reichardt, K.; Neto, D. D. Foliar and seed application of amino acids affects the antioxidant metabolism of the soybean crop. Frontiers in plant science 2017, 8(327), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano-Gámez, J. A.; El-Azaz, J.; Ávila, C.; de la Torre, F. N.; Cánovas, F. M. Enzymes Involved in the biosynthesis of arginine from ornithine in maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.). Plants 2020, 9(10), 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Mou, H. Production of a water-soluble fertilizer containing amino acids by solid-state fermentation of soybean meal and evaluation of its efficacy on the rapeseed growth. Journal of Biotechnology 2014, 187(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, G.; Todd, C. D.; Trovato, M.; Forlani, G.; Funck, D. Physiological implications of arginine metabolism in plants. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6(534), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Q. Connections between amino acid metabolisms in plants: lysine as an example. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11(928), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Macronutrients | ||||||||||||||||

| Prof. | pH | P | S | K | Ca | Mg | Al | H+Al | M.O. | SB | CTC | V | m | |||

| cm | CaCl2 | mg dm-3 | cmolcdm-3 | g dm-3 | cmolcdm-3 | % | ||||||||||

| 0-20 | 3,9 | 7,53 | 17,3 | 19 | 0,5 | 0,37 | 0,92 | 7,50 | 32,6 | 0,92 | 8,51 | 10,8 | 50,0 | |||

| 20-40 | 3,9 | 5,31 | 16,8 | 17 | 0,36 | 0,28 | 0,85 | 6,35 | 29,0 | 0,68 | 7,03 | 9,7 | 55,6 | |||

| Micronutrients | Granulometry | |||||||||||||||

| B | Na | Cu | Fe | Mn | Zn | Sand | Silt | Clay | Textural class | |||||||

| mg dm-3 | % | |||||||||||||||

| 0-20 | 0,41 | 0,0 | 0,39 | 48,53 | 9,67 | 2,53 | 33 | 8 | 59 | Clayey | ||||||

| 20-40 | 0,41 | 0,0 | 0,34 | 45,03 | 6,05 | 1,8 | 33 | 4 | 63 | M. Clayey | ||||||

| Fertilization | Source | Quantity |

| Correction | Dolomitic limestone1 | 3 t ha-1 |

| Sowing | Formulated 05-25-252 | 400 kg ha-1 |

| Application | Timing | Dose, commercial product, and active ingredients |

| 1ª | Pre-planting | 3,0 L ha-1 of Crucial (Glyphosate)+ 0,5 L ha-1 de Zethamaxx (Flumioxazina + Imazetapir) + 0,6 L ha-1 de U 46 (2,4-D) |

| TS | Sowing | 0,5 L 100 kg-1 de semente de Cropstar (Tiodicarbe + Imidacloprido) + Protreat (Tiram + Carbendazin) + 0,1 L 100 kg-1 of seed + 0,1 L 100 kg-1 of Cropseed (Bradyrhizobium japonicum) |

| 2ª | 20 DAE | 2,0 L ha-1 of Crucial (Glyphosate) + 0,8 L ha-1 of Cletodim (Viance) |

| 3ª | 40 DAE | 0,07 L ha-1 of Kaiso (Lambda-cialotrina) + 0,4 L ha-1 of Fox (Protioconazol + Trifloxistrobina) + 0,25% de Aureo |

| 4ª | 60 DAE | 0,07 L ha-1 of Kaiso (Lambda-cialotrina) + 0,4 L ha-1 of Fox (Protioconazol + Trifloxistrobina) + 0,25% of Aureo |

| 5ª | 70 DAE | 1,0 kg ha-1 of Perito (Acefato) + 0,2 L ha-1 of Valio (Orange oil) |

| 6ª | 80 DAE | 0,3 L ha-1 of Priori Xtra (Azoxystrobin + Cyproconazole) + 0,5% of Nimbus |

| Desiccation | 110 DAE | 2,0 L ha-1 of Gramoxone (Paraquat) + 0,2 L ha-1 of Valio (Orange oil) |

| Treatments | Formulation | Dose (g ha-1) | Stages |

| 1 | Aspartic acid | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 2 | Arginine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 3 | Cysteine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 4 | Cystine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 5 | Citrulline | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 6 | Phenylalanine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 7 | Glycine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 8 | Glutamine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 9 | Isoleucine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 10 | Leucine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 11 | Lysine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 12 | Methionine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 13 | Ornithine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 14 | Proline | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 15 | Taurine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 16 | Tyrosine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 17 | Threonine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 18 | Tryptophan | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 19 | Valine | 20 | V4 + R1 |

| 20 | - | - | - |

| FV | GL | Mean squares | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height | Number of internodes | Number of leaves | Number of branches | Number of pods | ||||||||||||||||||

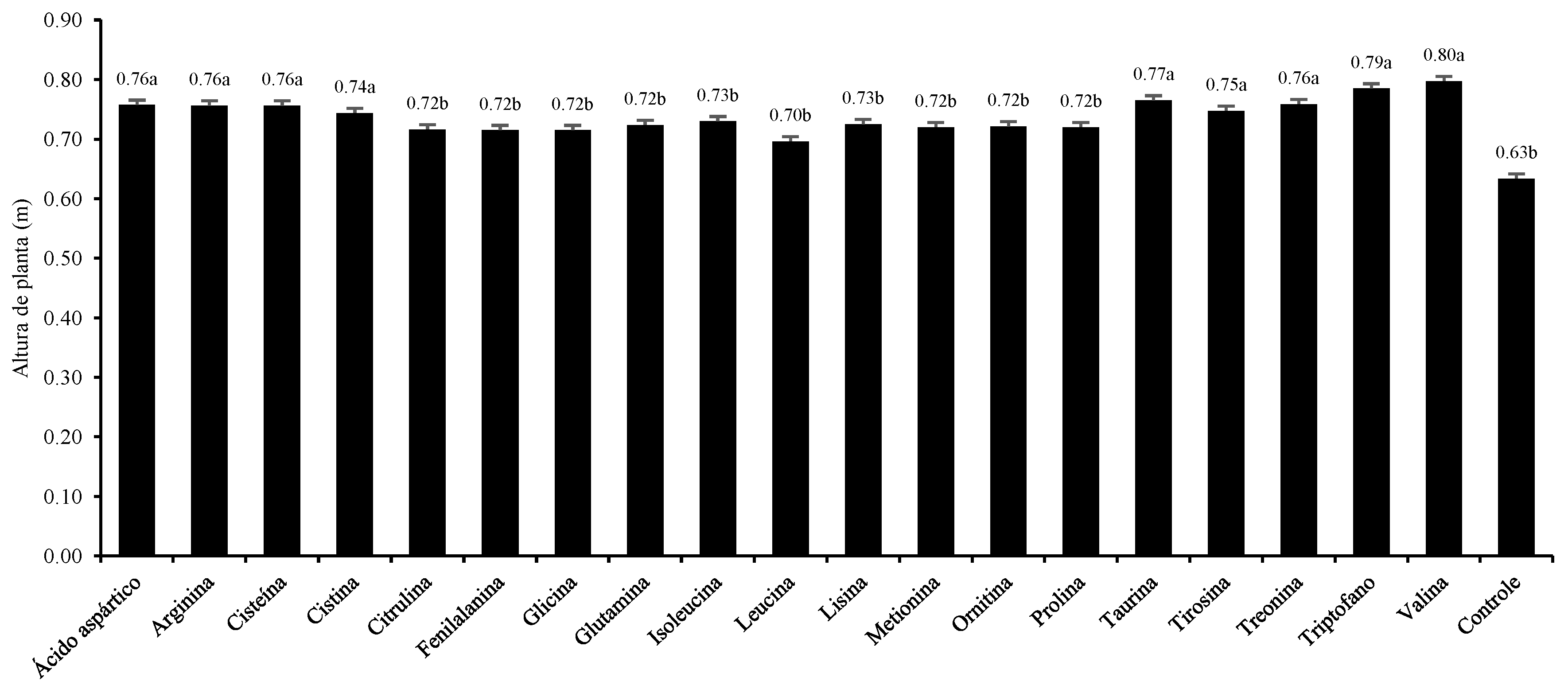

| Treatments | 19 | 49,041 ** | 0,753 ns | 14,249 ns | 1,648 ns | 148,684 ns | ||||||||||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 169,919 | 17,441 | 188,561 | 1,125 | 949,708 | ||||||||||||||||

| Residue | 57 | 18,318 | 2,391 | 20,947 | 1,289 | 241,116 | ||||||||||||||||

| CV (%) | 5,83 | 10,87 | 21,57 | 27,36 | 24,70 | |||||||||||||||||

| FV | GL | Mean squares | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N | P | K | Ca | Mg | S | |||||||||||||||||

| Treatments | 19 | 7,226 ns | 0,429 ns | 13,548 ns | 30,381 ns | 2,373 ns | 3,158 ns | |||||||||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 23,140 | 1,099 | 80,858 | 503,765 | 72,167 | 4,539 | |||||||||||||||

| Residue | 57 | 10,041 | 0,297 | 18,360 | 20,799 | 2,157 | 3,315 | |||||||||||||||

| CV (%) | 7,82 | 14,96 | 26,66 | 21,09 | 15,49 | 53,85 | ||||||||||||||||

| FV | GL | Mean squares | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fe | Mn | Cu | Zn | Mg | ||||||||||||||||||

| Treatments | 19 | 21947,183 ns | 2443,881 ns | 6,690 ns | 45,111 ns | 84,225 ns | ||||||||||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 536778,340 | 4079,361 | 30,227 | 371,738 | 97,923 | ||||||||||||||||

| Residue | 57 | 17753,138 | 2689,721 | 5,868 | 43,648 | 69,947 | ||||||||||||||||

| CV (%) | 30,95 | 82,07 | 19,19 | 16,26 | 19,59 | |||||||||||||||||

| FV | GL | Mean squares | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 100-grain weight | Grain productivity (kg ha-1) | |||||||||||||||||||||

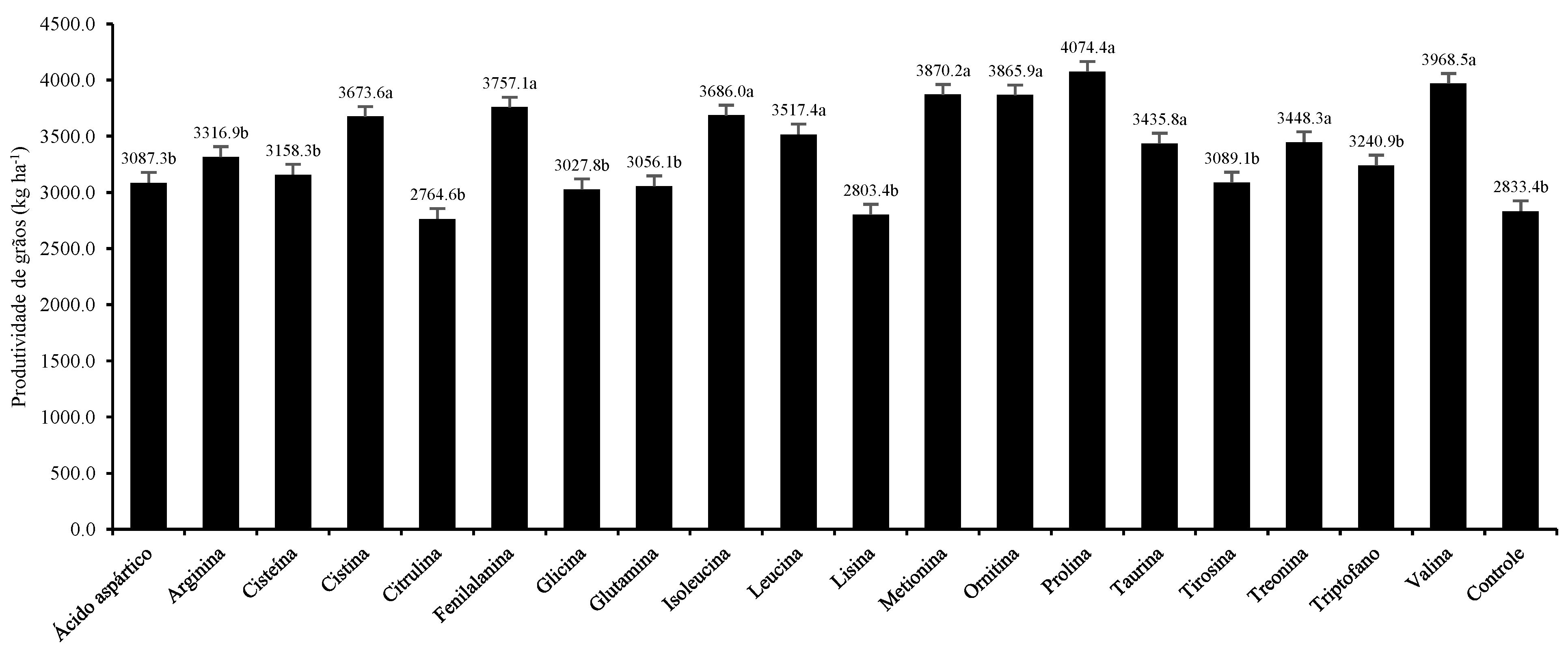

| Treatments | 19 | 0,634 ns | 495009,686 ** | |||||||||||||||||||

| Blocks | 3 | 10,627 | 15123,585 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Residue | 56 | 0,421 | 83400,751 | |||||||||||||||||||

| CV (%) | 3,45 | 8,53 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).