1. Introduction

In the present work, a method for the calculation of composite annular plates with heterogeneous metal facings is proposed. Numerous analysis results are presented, with primary attention focused on the dynamic responses of plates under loads acting in the plane of the facings. The evaluation of the loss of plate stability, which is accompanied by a sudden change in the shape of the plate at a specific critical load, shows the sensitivity of the examined structure to its geometrical and material parameters. The application of a heterogeneous structure with smoothly functionally graded material of facings allows the construction of new plate structures with a classical three-layer layout, whose mechanical properties can fulfil the required specifications. By evaluating the buckling phenomenon for two material models, resulting from the radial distribution of the extreme material properties of steel and aluminium, a thorough numerical analysis and discussion of the obtained results have been conducted. The calculation results were obtained for two computational models: an analytical and numerical model based on the finite difference method (FDM), and a numerical model using finite elements. Special attention was given to the computational efficiency of combining analytical and numerical calculations through approximation methods, including orthogonalization and finite differences. The presented calculation techniques and evaluation of buckling behavior complement research in composite plates, creating opportunities for further exploration of structures tailored to specific requirements.

The search for new composite structures that meet technical requirements continues. Plates, including the annular plates examined in this work, are widely used construction elements in various industries, such as mechanical engineering, civil engineering, nuclear, and aerospace applications. Composite three-layered plates with a classic structure, composed of thin metal facings and a thicker foam core, have been extensively analyzed and applied in practice.

A growing expectation in many industrial sectors is the design of structures dedicated to precise, specific technical solutions. Predicted reactions of elements demonstrating enhanced capabilities of specially composed structures, compared to classical designs, directly fulfill this expectation.

The technical potential of such structures for three-layered annular plates can be realized through the use of heterogeneous elements. Radially variable material properties of the metal facings enable the construction of new layered plates. Recognition of their static and dynamic behaviors, to assess stability loss, is the focus of the research undertaken in this work. It should be emphasized that buckling studies of layered annular plates, including three-layered plates, are presented in numerous scientific works. Thematic groups can be distinguished based on the modeling and load conditions of the examined annular plates. Thermo-mechanical environments are dominant, and most studies focus on plates with transverse material gradation.

The nonlinear bending and post-buckling behavior of a functionally graded material (FGM) annular sector plate is presented in work [

1]. The plate is composed of two materials: ceramic and metal, with material parameters continuously varying across the plate thickness. The effects of material and geometrical parameters on plate responses have been examined. Two kinds of boundary conditions have been applied. Numerical calculations were conducted using graded finite elements. The free vibration analysis of the annular sector plate is presented in work [

2]. The plate is also composed of metal and ceramic. Two theories were used in modeling: first-order shear deformation and Love’s theory. The influence of different geometrical sector ratios and material parameters on the frequencies of the plate sector with various boundary conditions is presented. The dynamic analysis of bidirectional FGMs in a rotating annular plate with variable thickness, including the effects of geometric imperfections and different boundary conditions, is presented in work [

3]. The FGM plate material parameters vary in both the radial and axial directions. The effect of specific geometrical ratios of the annular plate on low-velocity impact behavior is demonstrated through numerous results. Effects of thermo-mechanical loading, geometrical parameters, and boundary conditions on the large deflection behavior of annular and circular FGM plates are presented in paper [

4]. The material grading through the plate thickness is expressed using a power law. Large deflections are derived from Karman’s equations, which include thermal relations. The frequency analysis of an FGM annular plate under hygrothermal effects, with graded material across the plate thickness, is presented in paper [

5]. Finite element analysis was applied to clamped–clamped and clamped–free boundary conditions for the examined plate model. Free vibration analysis of FGM annular and circular plates is presented in paper [

6]. Material parameters are distributed across the plate thickness according to the power law. The effects of graded material parameters and different geometrical measurements on the natural frequency values are examined. The static temperature analysis of a three-layered annular plate with heterogeneous facings made of material with radially variable parameters is considered in work [

7]. Material properties are defined by specified exponent functions. The effects of material and geometrical parameters in two plate models, built using FDM and finite element methods (FEM), on the plate response in a thermal environment are shown. The influence of a time-dependent temperature field and the effect of a stationary temperature field on the stability of a three-layered annular plate are presented in works [

8] and [

9]. Temperature changes, expressed as gradients in the plate’s radial direction, are considered.

Complex loading fields, such as magnetic, electric, and piezo-magnetic, in addition to thermo-mechanical loads, provide additional effects that alter plate responses. The free vibration analysis of FGM annular plates integrated with piezo-magneto-electro-elastic layers is shown in paper [

10]. The effect of temperature environments, corresponding to various plate parameters, has been examined. Stress and displacement analysis of annular FGP plates subjected to complex loads, including transverse mechanical and magnetic forces, is presented in work [

11]. Both the elastic modulus and magnetic permeability coefficient vary across the plate thickness according to a power function. Functionally graded piezoelectric annular plates on Winkler foundations are investigated in work [

12]. The free vibration problem has been solved semi-analytically.

The behavior of plate elements is also controlled by structural properties, such as porosity. Classical functionally graded annular and circular plates with porosity are examined in paper [

13]. Three porosity models were assumed: uniform, O-shaped, and X-shaped. The analyses focus on the basic natural frequencies. The effects of material and geometrical parameters, as well as porosity distribution, on axisymmetric bending of FGM annular or circular microplates under thermal and mechanical loads are presented in paper [

14]. Nonlinear finite element models with various porosity distributions have been examined.

Geometrical or material heterogeneity creates complex models that require specialized solution techniques. To understand not only the macro-scale impact of structures but also the influence of microstructure on plate responses, tolerance-based modeling techniques are used. These approaches are applied to various problems, including vibrations, stability, thermo-elasticity, heat conduction, and temperature-dependent behavior [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The dynamic stability of annular plates subjected to mechanical and thermal loads is presented in works [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The studies by Chen et al. [

22] and Wang et al. [

23] are exemplary, addressing the dynamic stability analysis of mechanically loaded sandwich annular plates. The dynamic stability of three-layered annular plates subjected to loads acting on the facings is presented in works [

24] and [

25]. Plate responses to forces increasing over time are analyzed depending on material, geometrical, and loading parameters. Two plate models, built using FDM and FEM, were examined. A buckling analysis of an FGM sandwich square plate with a metal core is presented in work [

26], examining the effects of geometry, material parameters, and boundary conditions.

2. Problem Analysis

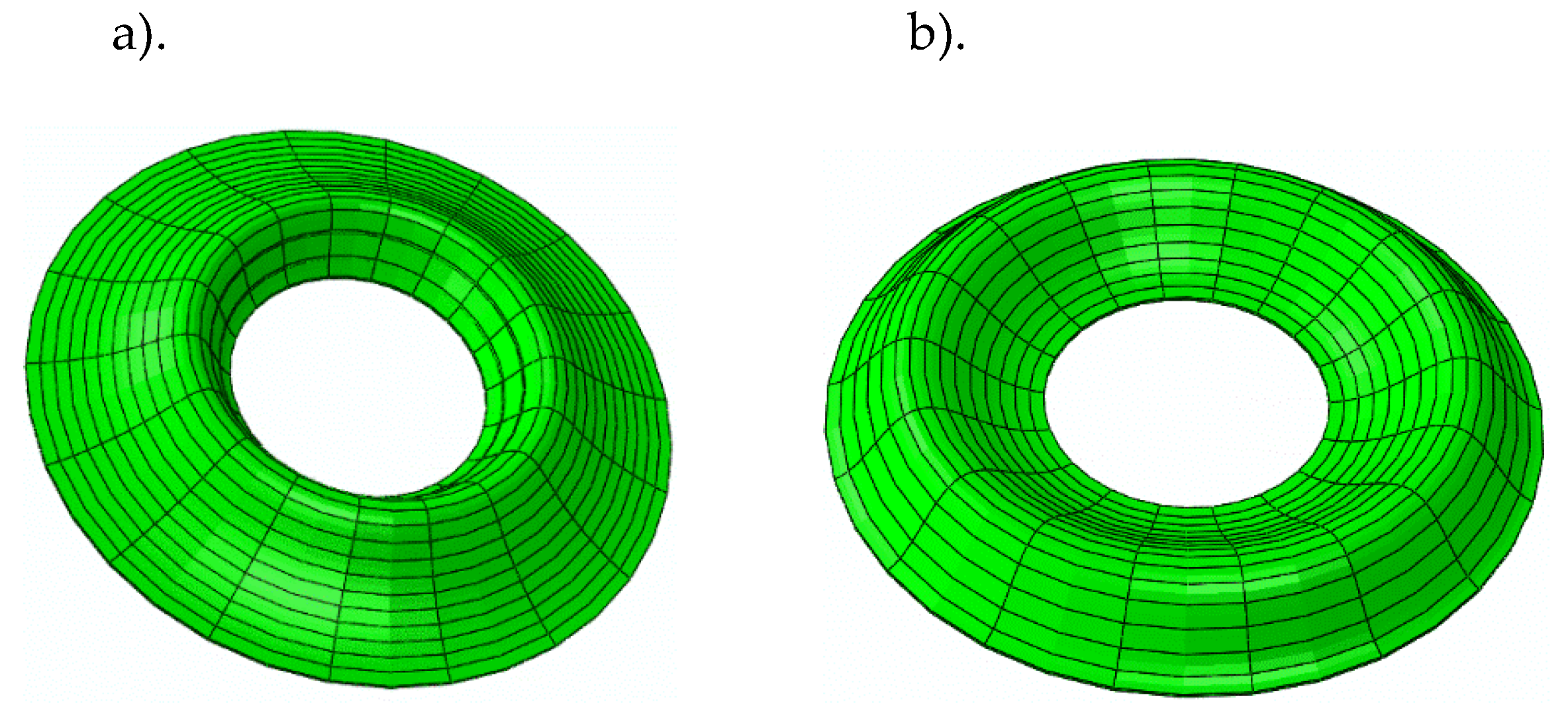

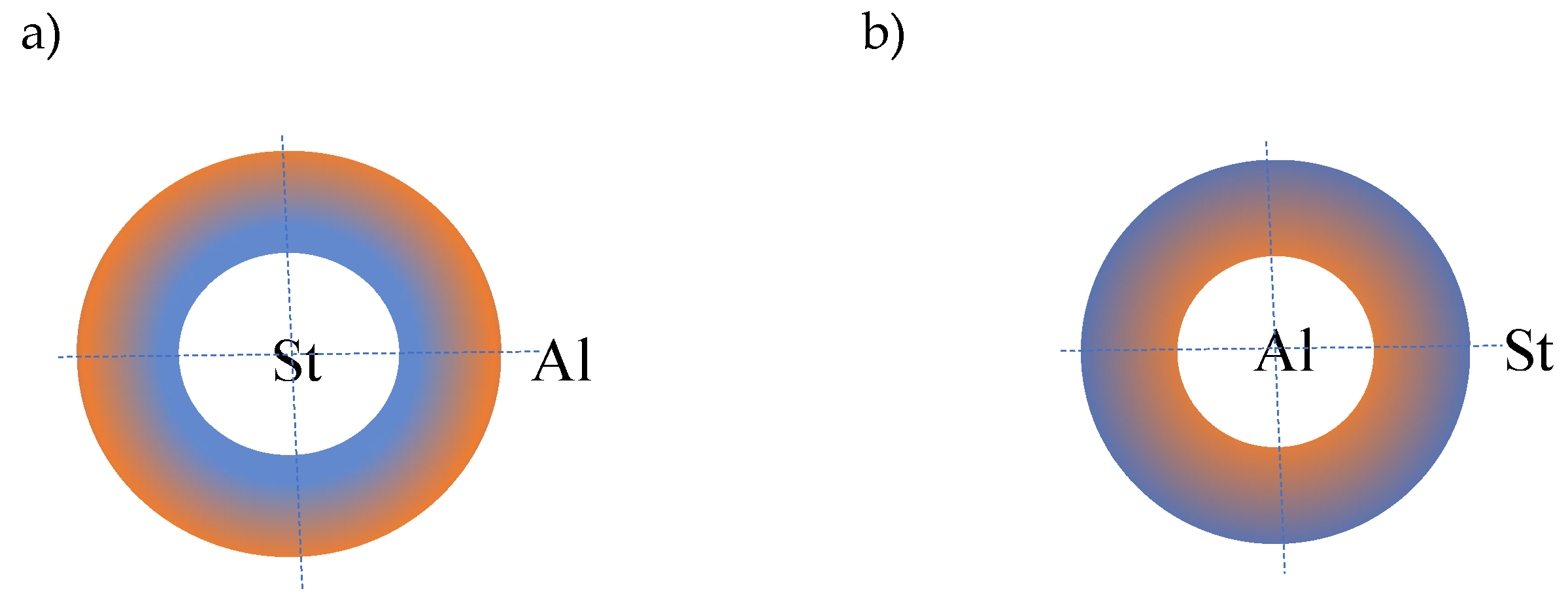

The object of this analysis is a three-layered annular plate, whose outer layers are made of FGM facings. The facings are composed of two metals: steel and aluminium. The material parameters change in the plate’s radial direction according to the functional relation given by Eq. 2 for two material models: St-Al, where steel is on the inner plate edge and aluminium on the outer edge, and Al-St, where aluminium is on the inner plate edge and steel on the outer edge (see

Figure 1).

The analyzed examples include plates with FGM facings and homogeneous facings. The core material is homogeneous, made of polyurethane foam.

The plate is subjected to in-plane forces applied on the inner or outer edge of the facings. In the dynamic analysis, forces increase over time at a specified loading rate. The inner or outer edge is loaded with a uniformly distributed load, linearly increasing in time according to the following formula:

where

p(t) is the compressive stress,

s is the rate of plate loading, and

t is time.

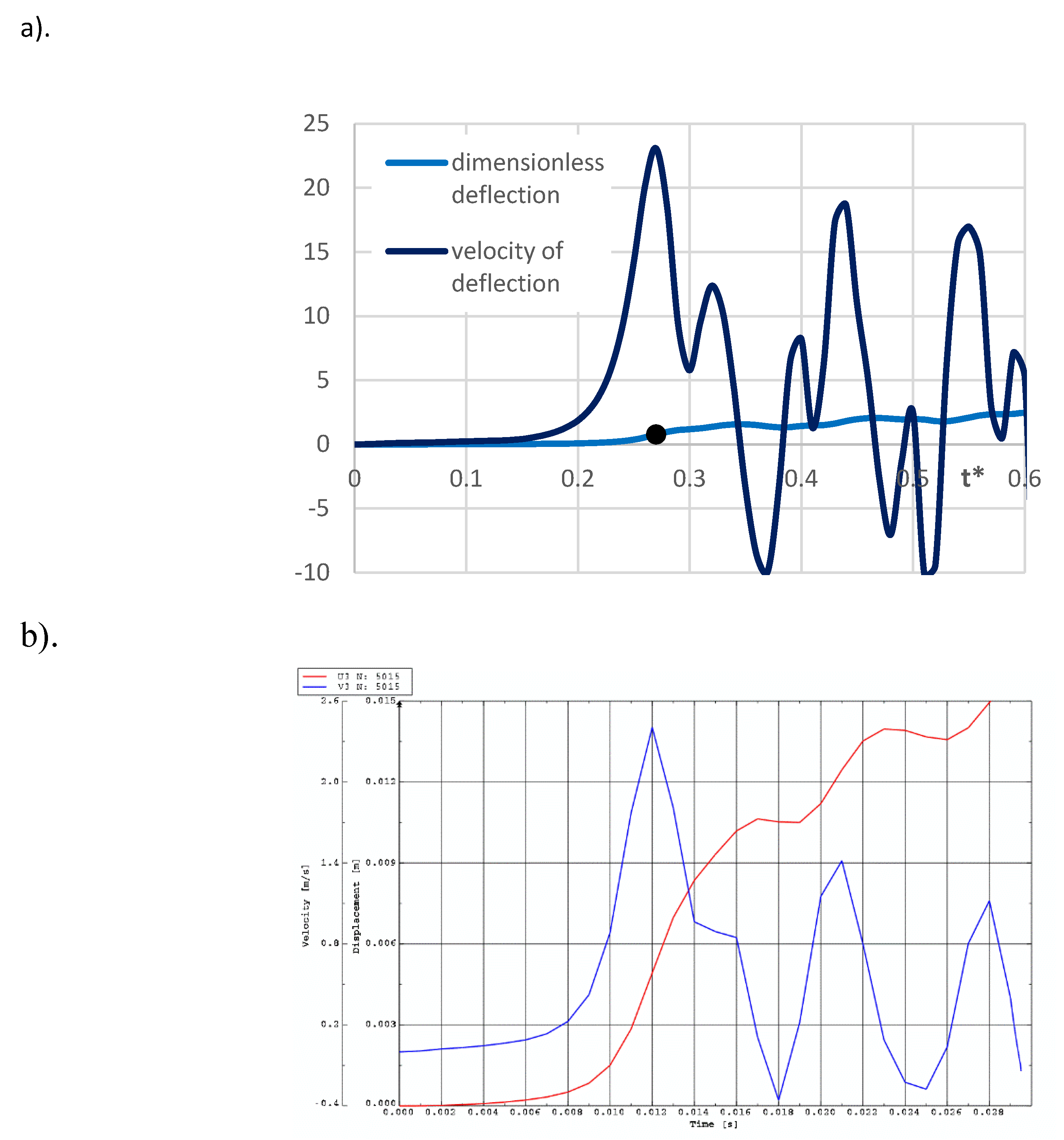

The main focus of this study is the plate’s buckling behavior. The plate is initially imperfect and can lose its stability in complex forms, with radial and circumferential buckling waves. The main observed examples are buckling with a half-wave in the radial direction and several waves in the circumferential direction, or the axisymmetric form without circumferential waves. Critical dynamic parameters, including the load

pcrdyn, time

tcr, deflection

wcr, and mode

m (defined by the number of circumferential waves), characterize the dynamic stability of the examined FGM plate. The moment of the loss of plate stability occurs when the speed of the point of maximum deflection reaches its first peak. This criterion for dynamic stability loss is presented in work [

27].

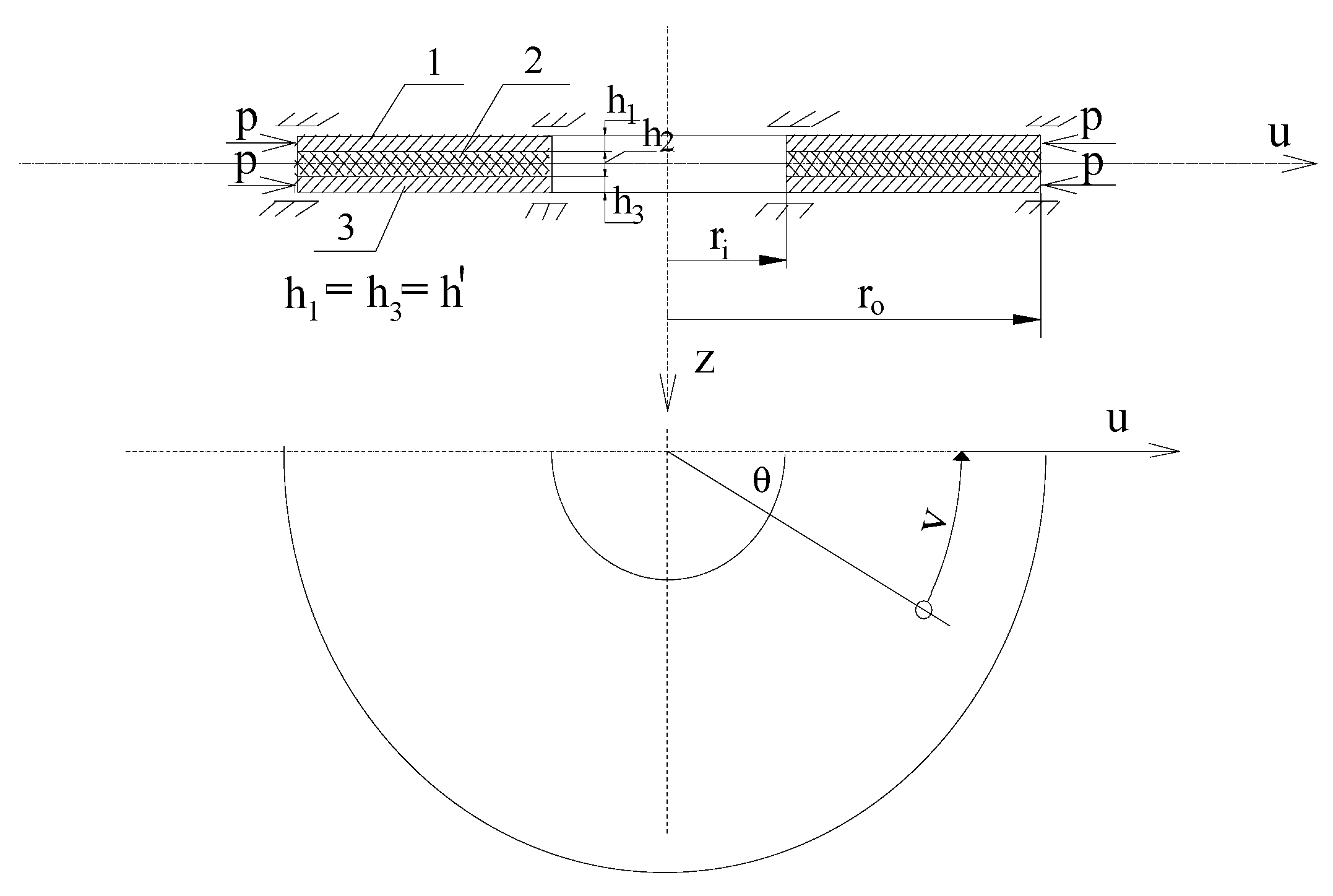

The plate scheme is shown in

Figure 2. The plate consists of three layers: FGM facings and a homogeneous core, forming a classical sandwich cross-section with thinner facings and a thicker core. The analyzed plate is slideably clamped at both the inner and outer edges.

3. Solution Procedure

The problem is solved using a combination of analytical and numerical calculations. It is based on the orthogonalization method for eliminating the angular variable

θ (see

Figure 2) and the FDM. The classical theory [

28] of three-layered plate structures has been adopted. It is based on the assumptions of the broken-line hypothesis and the interaction of stresses between plate layers: normal stresses are carried by the facings, while shear stresses are carried by the core.

Additionally, an FEM plate model has been developed using the finite elements. The FEM plate structure corresponds to the classical formulation used for the FDM plate model.

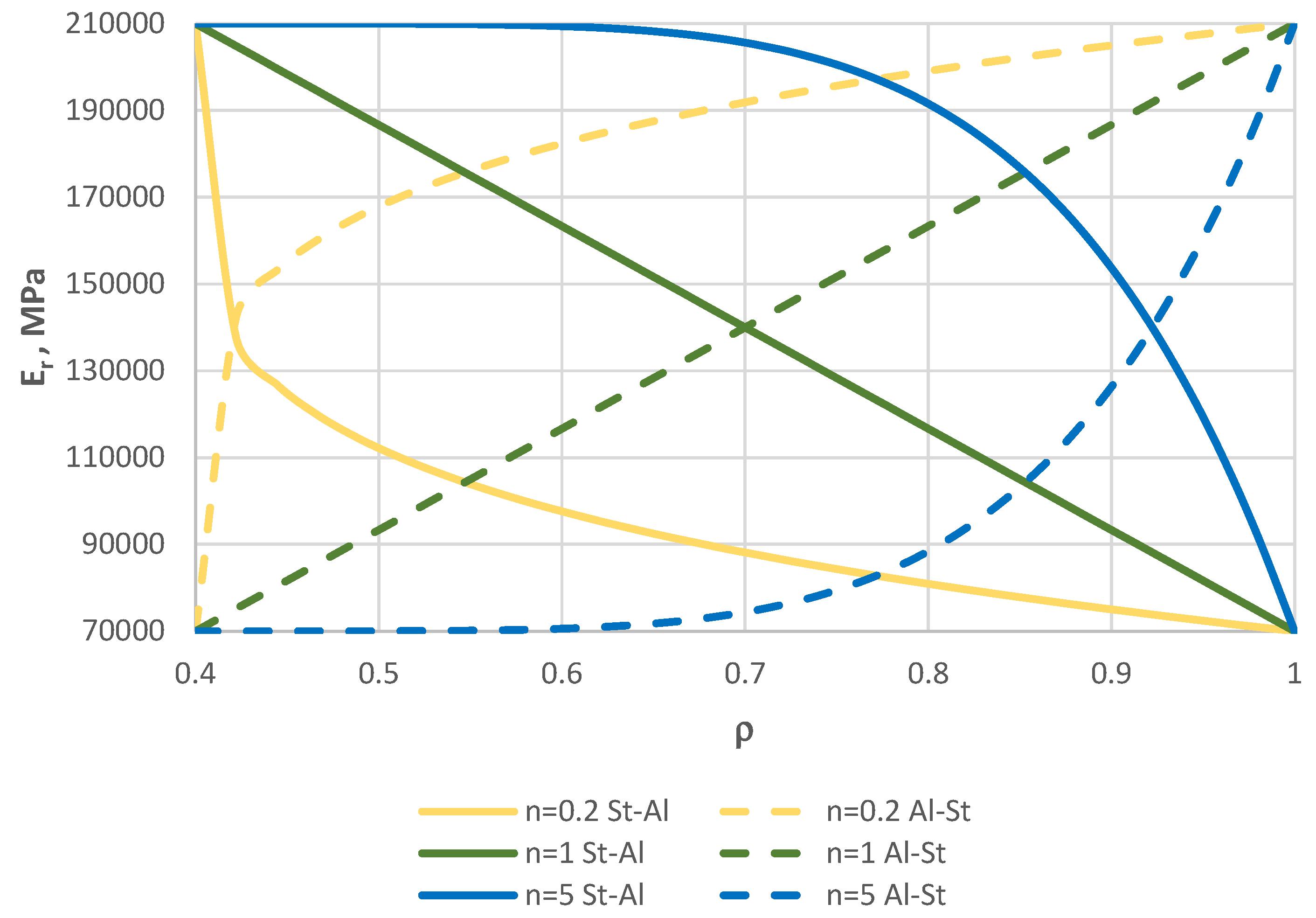

3.1. Material Model

The radial changes of the FGM facing material are smooth and follow a power function:

where

ri and

ro are the inner and outer plate radii,

r is the plate radius, and

n is the power-law exponent.

The material parameters of the facings, such as Young’s modulus

Er, Kirchhoff’s modulus

Gr, Poisson’s ratio

νr, and mass density

μr depend on the plate radius

r and the power-law exponent

n. They are calculated according to the following equation:

where W1 and W2 are the values of the material parameters (Er, Gr, νr, and μr), VV is the rate of material variation in the radial direction, and W is the value of the facing material parameters at the plate point determined by the radius r. The distribution of material parameters in the facing plane is axisymmetric.

The facings are composed of two materials: steel, with Young’s modulus

ESt = 210,000 MPa, and aluminium, with Young’s modulus

EAl = 70,000 MPa, located at the selected edges of the plate. Between the edges, the facings’ material parameters vary according to the selected power-law exponent

n (see Eq. 2), with

n = 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5.

Figure 16 in Chapter 4.6 shows the distribution of Young’s modulus along the plate radius for three values of

n (0.2, 1, 5) for the two plate material models St-Al and Al-St (see

Figure 1). The effect of the material model on the stability results is discussed in this Chapter 4.6.

3.2. Technique of the Problem Solution Using the FDM

The solution process is based on the method presented in previous works [

24,

25,

29,

30]. The solution technique uses both analytical and numerical calculations. The analytical calculations lead to the main differential equation for the deflections of the analyzed composite plate in the dynamic problem:

where

w is the total deflection,

wd is the additional deflection, and

δ, γ are the differences of radial

u1,

u3 and circumferential

v1,

v3 displacements of points on the middle surfaces of the facings, expressed by

δ = u3 - u1 and

γ = v3 - v1, respectively.

N1 = 2

Dr,

,

,

are the rigidities of the plate facings;

h is the total plate thickness,

H′ = h′ + h2, where

h′ is the facings’ thickness and

h2 is the core thickness.

Φ is the stress function,

M = 2

h′μr + h2, and

μ2 is the core mass density.

Equation 4 was derived after formulating the dynamic equilibrium equations for each plate layer, assuming the deformation of the middle surface of the facings follows the nonlinear von Kármán theory, and describing the transversal geometry of the core deformation based on the linear broken line hypothesis. The equations of Hooke’s law were applied:

where σr is the radial stress, σθ is the circumferential stress, and τrθ is the shear stress.

Then, the resultant transverse forces in radial and circumferential directions and the resultant membrane forces expressed by the stress function were formulated, assuming the initial conditions that both the additional deflection

wd and the speed of the additional deflection

wd,t for time

t = 0 are equal to zero. Boundary conditions are expressed for the total deflection

w and the differences of displacements in radial

δ and circumferential

γ plate directions:

Loading conditions are defined for the plate edges: inner for radius

ri or outer for radius

ro, respectively:

The quantities d1 and d2 are equal to 0 or 1.

Plate geometry is modeled with the preliminary deflections. The shape is determined by the combination of the axisymmetric component and depends on the number

m of circumferential waves [

31,

32]:

where the dimensionless predeflection is , the dimensionless plate radius is , ξ1 and ξ2 are numbers that calibrate Eq. 8, and η(ρ) = ρ4 + A1ρ2 + A2ρ2lnρ + A3lnρ + A4, with Ai satisfying the conditions of clamped edges.

The shape functions used in the solution of the problem include the additional deflection

[

31,

32], the functions of the radial and circumferential facings displacements

,

[

24,

25], and the stress function

[

31,

32]:

where

E is the established value of the Young’s modulus (

ESt for the St-Al plate model or

EAl for the Al-St model),

, and

m is the number of circumferential waves corresponding to the number of waves shaping the plate imperfection.

The solution technique uses the orthogonalization method to eliminate the angular variable

θ, along with the FDM, which approximates the derivatives with respect to

ρ using central differences at discrete points. The main equation of the system of differential equations has the following form [

24,

25,

30]:

where the vector

contains elements expressed by the derivative of the additional deflection with respect to time

t, and the number

K is given by

. Here,

K7 represents the rate of mechanical loading growth calculated as the quotient of

s (see Eq. 1) to the assumed value of the critical static load

pcr, with

. The vector

contains the additional deflections. The vector

contains the plate’s material and geometrical parameters, initial and additional deflections, number

m, and dimensionless radius

ρ. The matrix

contains the plate’s material and geometrical parameters, number

m, and parameter

b, which represent the interval in the FDM.

The Runge–Kutta integration method for the initial state of the plate was used in the numerical solution. Results of the time history of deflection parameters are presented for the dimensionless time t* = t ⋅ K7, which was used in the numerical calculation procedure.

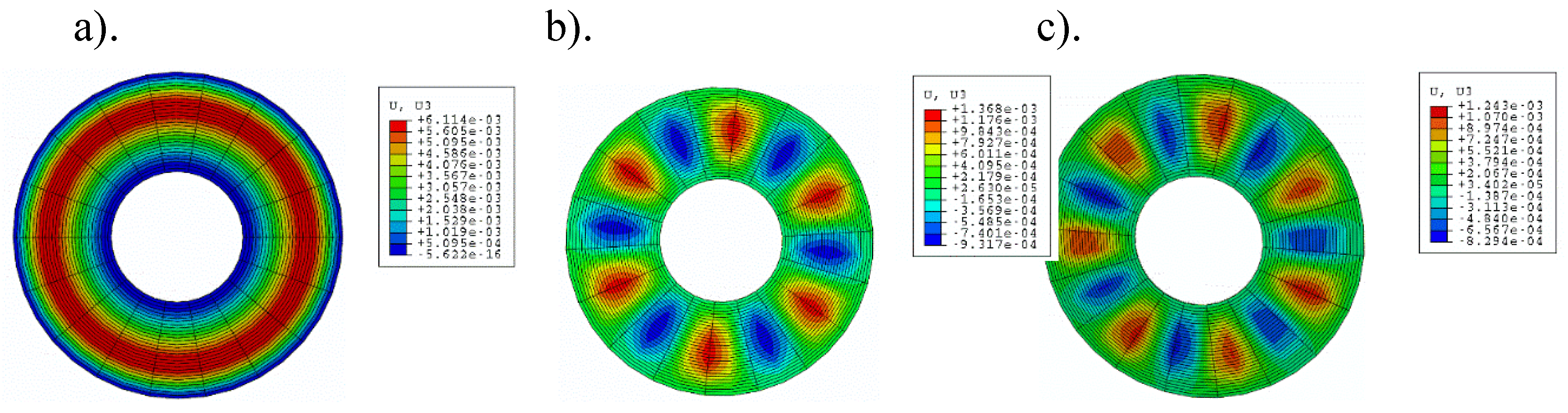

3.3. Technique of the Problem Solution Using the FEM

The plate model was built using shell and solid elements. Shell elements were used to build the facing mesh, and solid elements were used to build the core mesh. The outer surfaces of the facing mesh elements were connected to the outer surfaces of the core elements using surface contact interaction. Calculations were carried out using the ABAQUS system at the Academic Computer Center CYFRONET-CRACOW via the PLGrid Portal under the awarded grant named plgplate1. The Dynamic option of the ABAQUS system was used in the dynamic stability analysis. Static analysis to calculate the critical static load was carried out using the eigenvalue buckling procedure.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the dynamic responses of composite annular plates with facings made of FGM. Alternating changes in material properties create two types of plate models with facings of steel-aluminium or aluminium-steel. In these models, the material with steel or aluminium parameters adheres to the inner edge, while aluminium or steel adheres to the outer edge, respectively. Radial changes of the material parameters are determined by a power function, in which the power-law exponent n takes the values n = 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5. Numerical calculations have been conducted for two models: one using the FDM and the other using the FEM.

The results of the numerical calculations are presented with consideration of the evaluation of the plate critical state parameters. The main observations concern the critical dynamic loads, which are complemented by the evaluation of the changes in values determined for the static state of the plate, namely the critical static loads. The discussion of the calculation results highlights the importance of the radial distribution of the facing material in relation to the type of plate edge loading: inner or outer. In the pursuit of building composite plate structures with greater resistance to buckling, attention is focused on cases of plates with higher critical parameter values. Specifically, these are the cases in which the values of pcrdyn or pcr approach their maximum values, which are associated with steel facings. The most appropriate model is the St-Al plate model with an exponent of n = 5 for the material power function under outer edge loading, or a plate with n = 0.2 under inner edge loading. The benefit of using FGM material with radially variable parameters is a significant reduction in plate weight with only a slight decrease in stability-related properties.

The computational models, built according to the assumptions and limitations of the applied approximation methods, were tested. The static and dynamic responses of both FDM and FEM plate models are consistent. Observed differences in critical load values mainly concern the plate with n = 0.2, whose facings are more flexible due to the increased contribution of aluminium parameters. The proposed analytical and numerical FDM solution procedure demonstrates techniques for modeling complex plate structures and enables rapid, effective calculations for variable plate parameters. From a practical point of view, the effectiveness of the proposed procedure is high.

It is possible to extend the analyses to cases of plates whose facing material functions have various forms. The presented numerical research should be complemented by experimental analyses. Additionally, considering a heterogeneous material for the plate core could significantly enrich the evaluation of the examined composite plates. This topic will be addressed in future work.

Figure 1.

Plate material models: a) St-Al, b) Al-St .

Figure 1.

Plate material models: a) St-Al, b) Al-St .

Figure 2.

Plate scheme compressed on the outer edge (1, 3 – thin facings with thickness h’, 2 – foam core with thickness h2).

Figure 2.

Plate scheme compressed on the outer edge (1, 3 – thin facings with thickness h’, 2 – foam core with thickness h2).

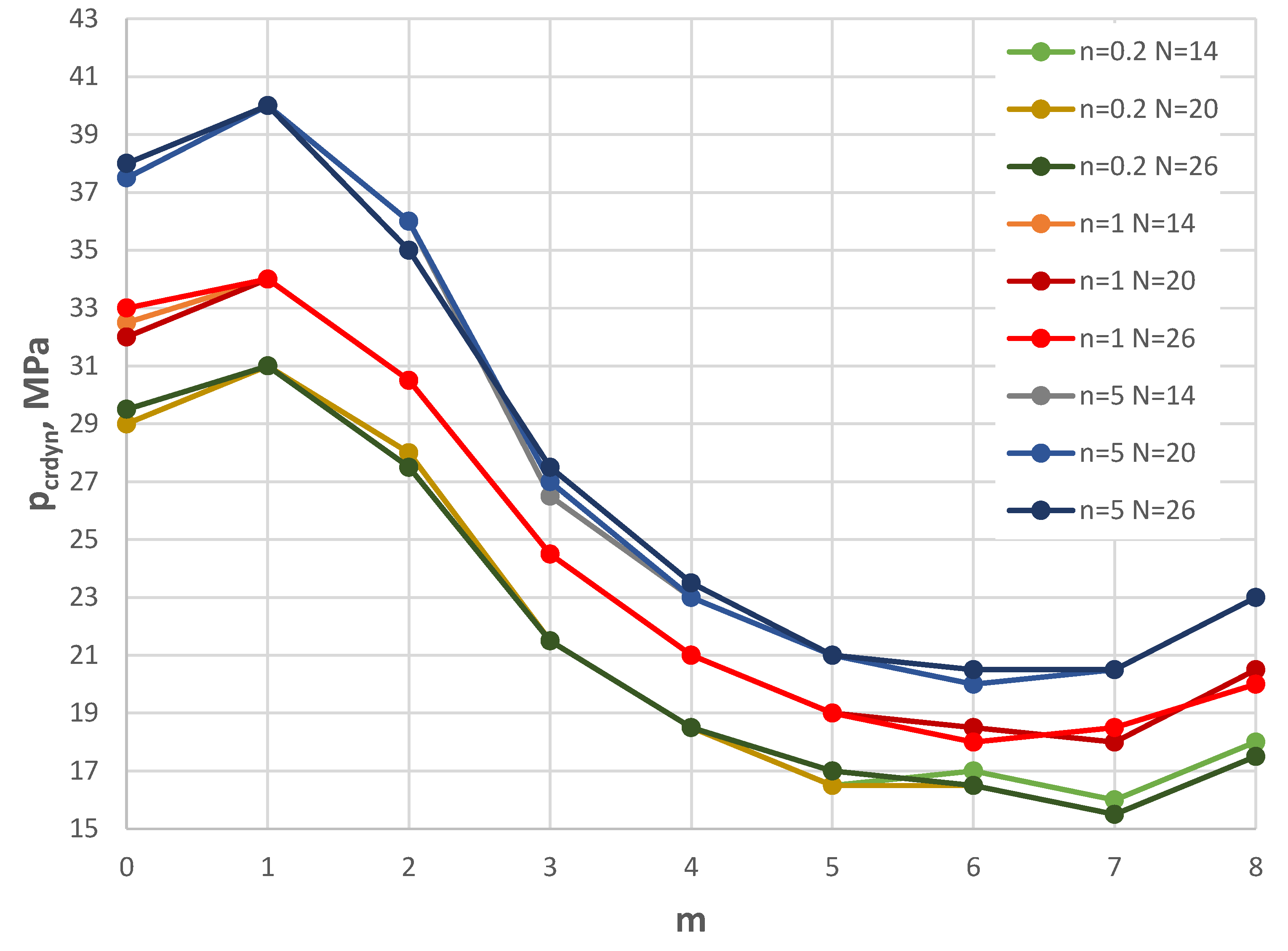

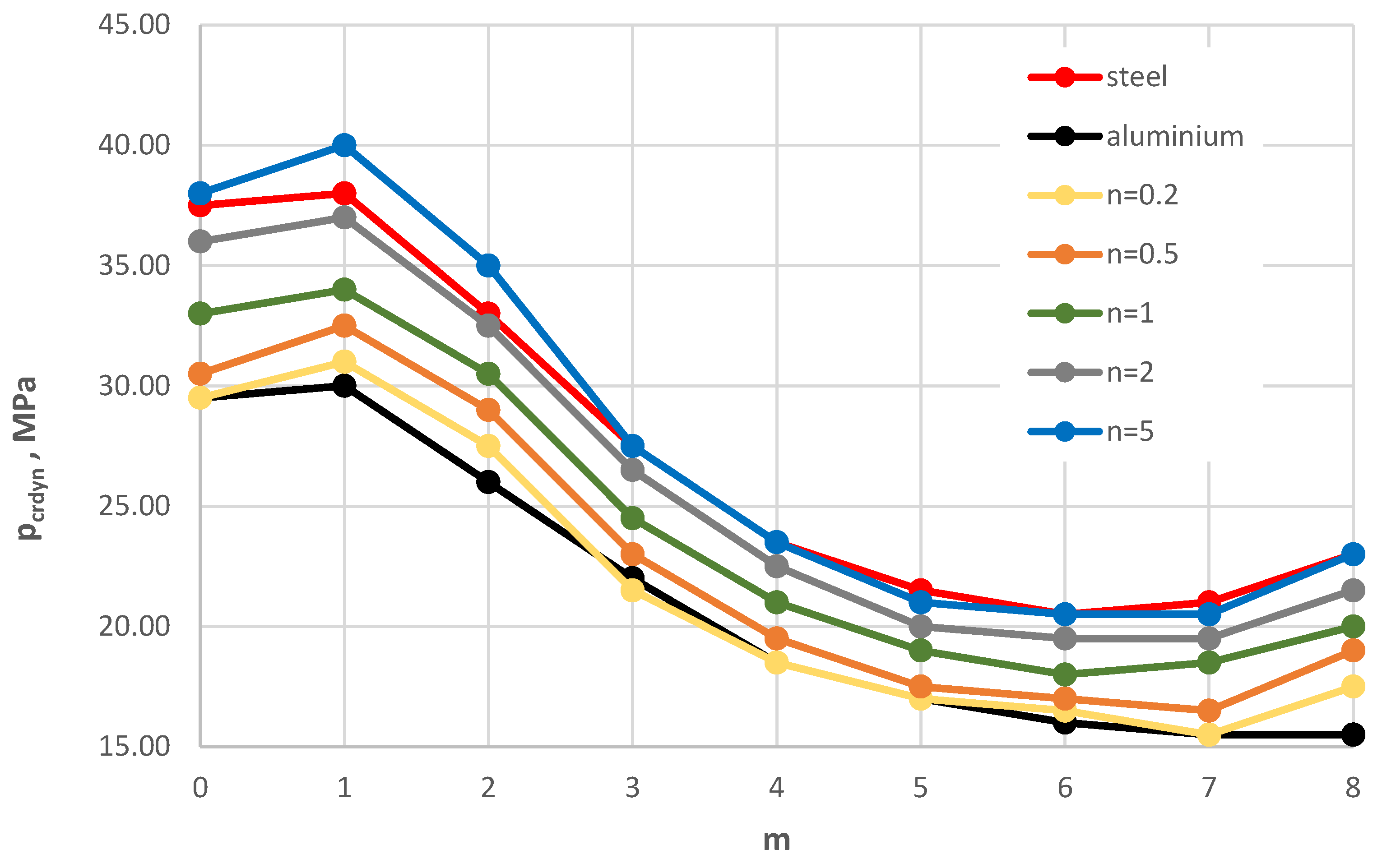

Figure 3.

Distribution of the critical dynamic load pcrdyn versus mode number m for the St-Al plate model loaded on the outer edge with various values of n and number N of discrete points.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the critical dynamic load pcrdyn versus mode number m for the St-Al plate model loaded on the outer edge with various values of n and number N of discrete points.

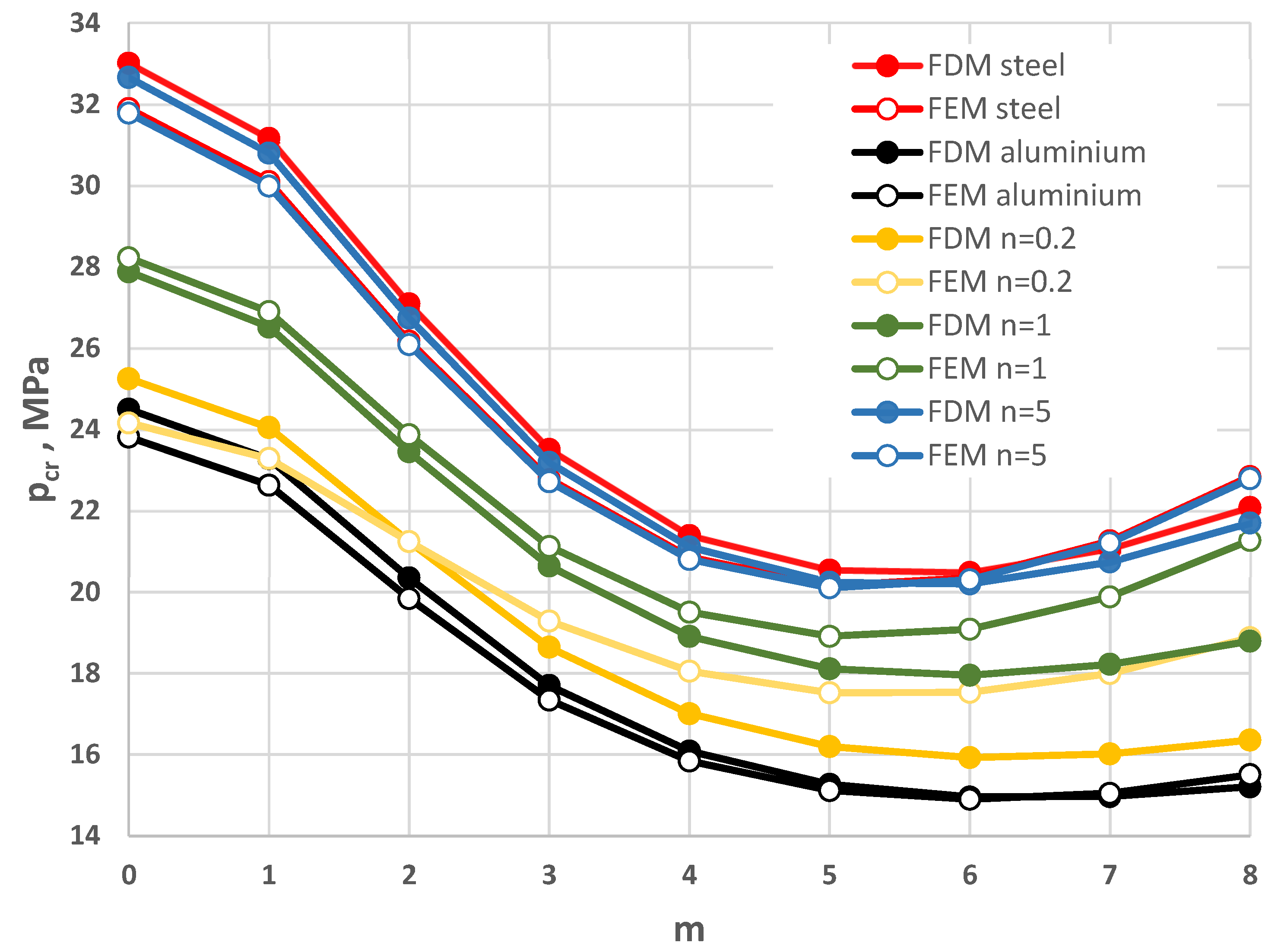

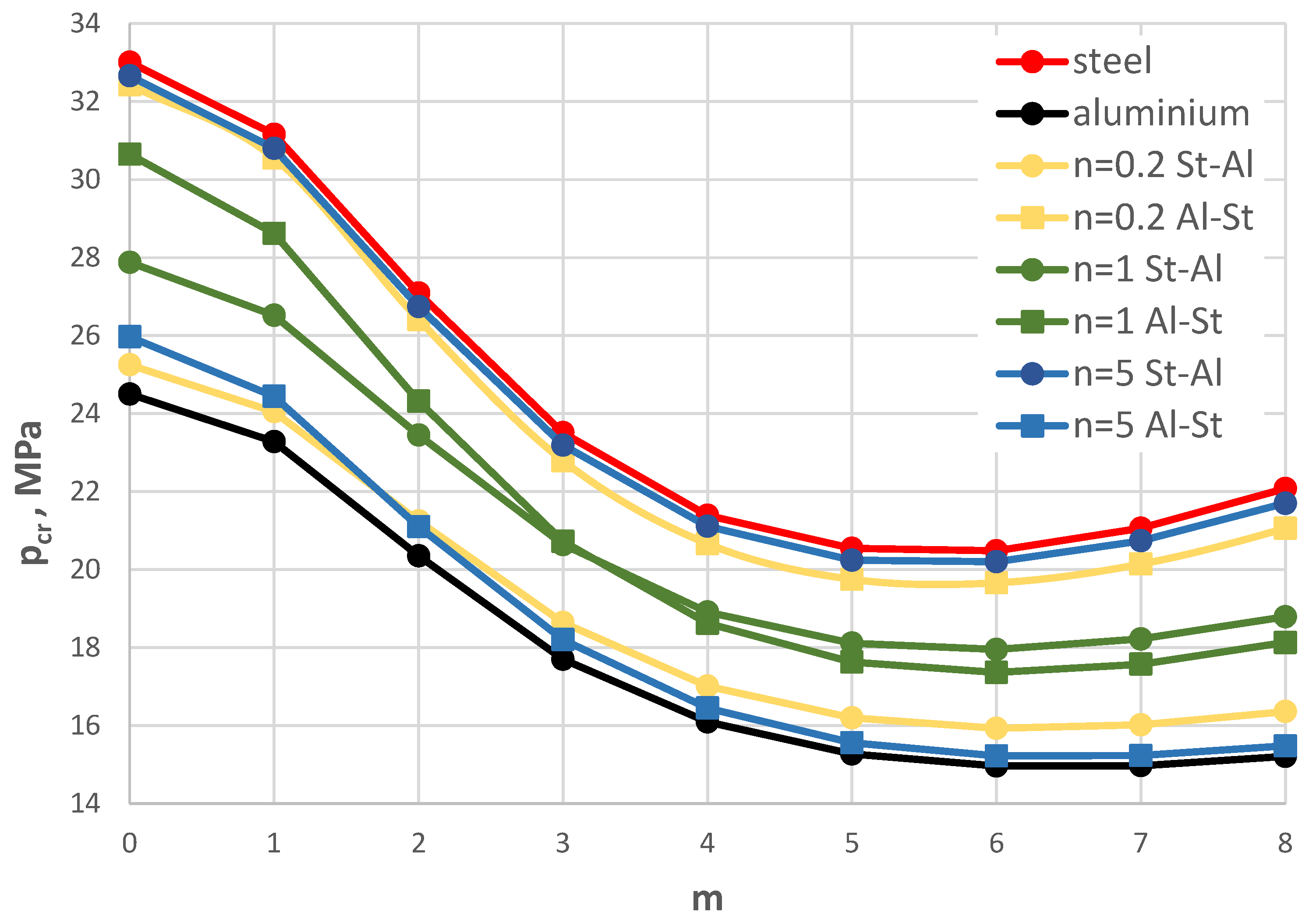

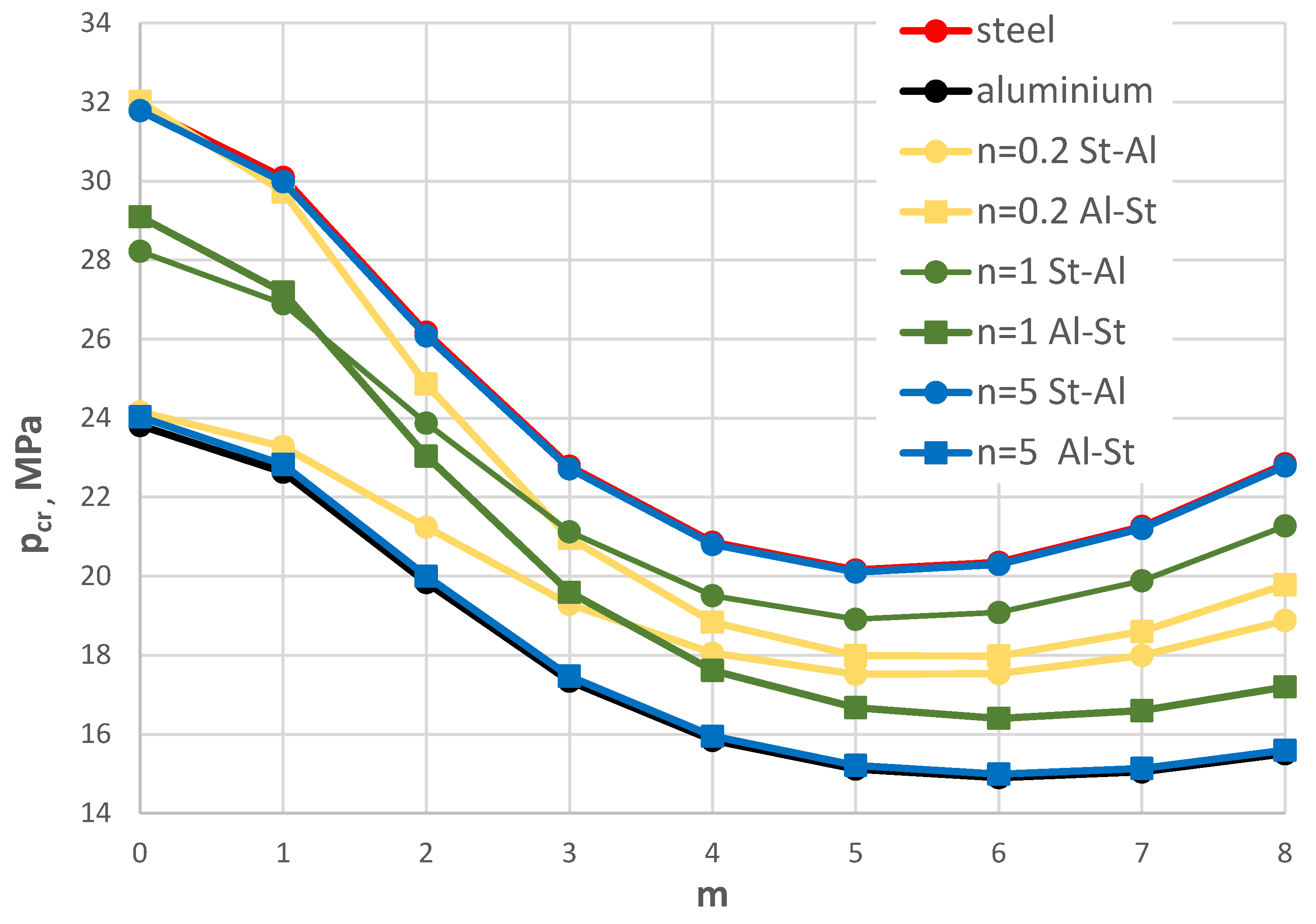

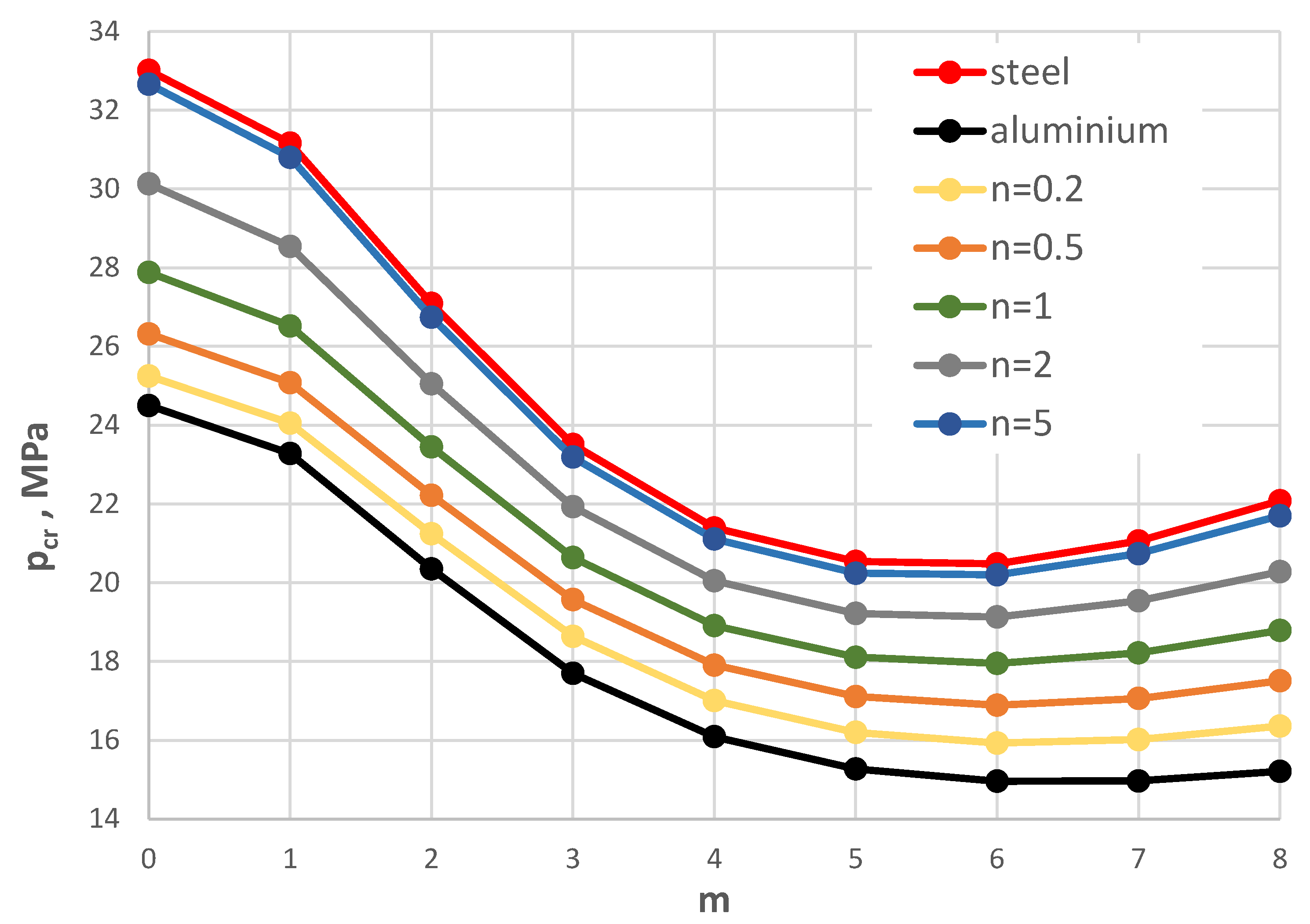

Figure 4.

Distribution of the critical static load pcr versus mode number m for St-Al, steel, and aluminium plate models.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the critical static load pcr versus mode number m for St-Al, steel, and aluminium plate models.

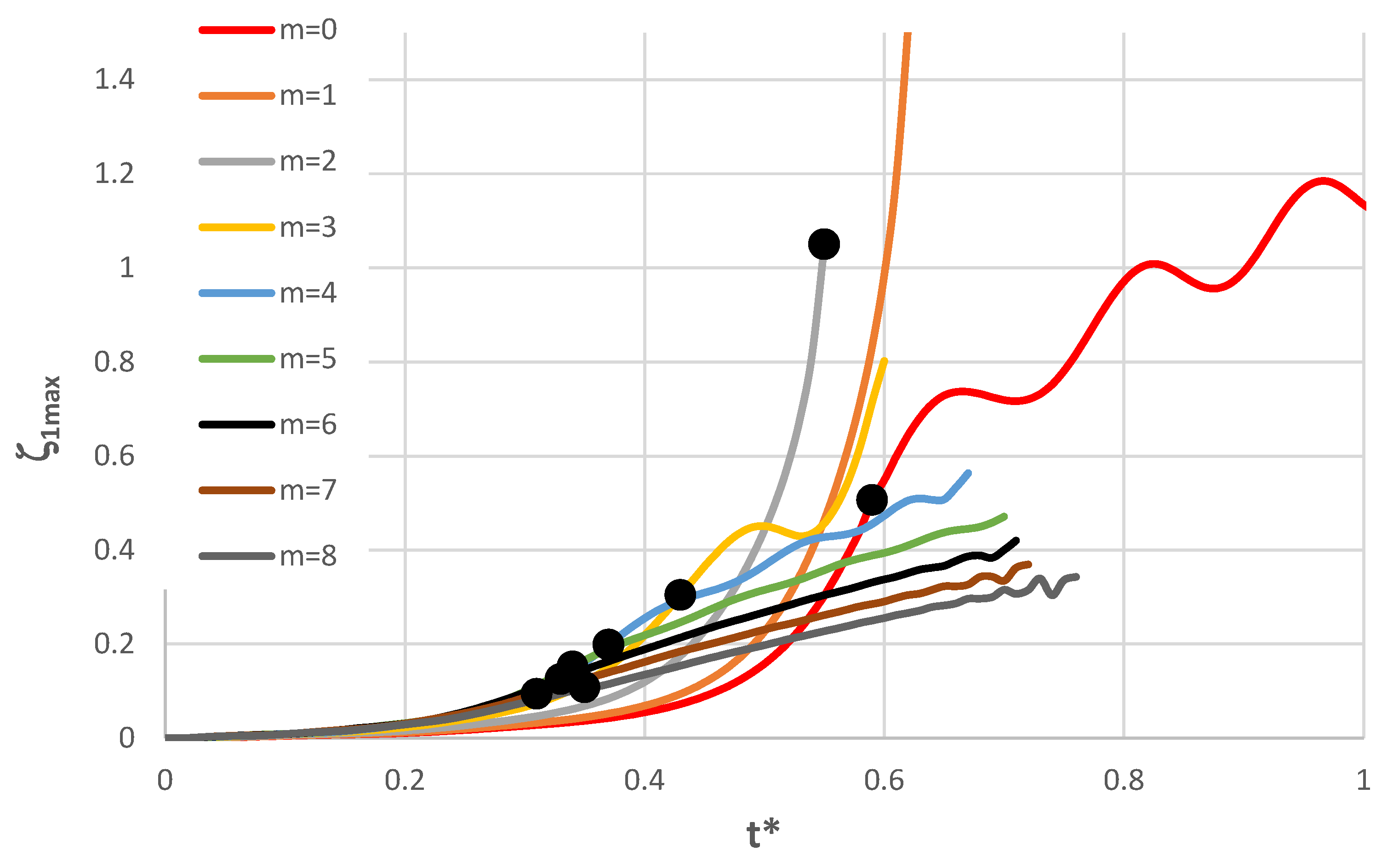

Figure 5.

Distribution of the critical dynamic load pcrdyn versus mode number m for St-Al, steel, and aluminium plate models.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the critical dynamic load pcrdyn versus mode number m for St-Al, steel, and aluminium plate models.

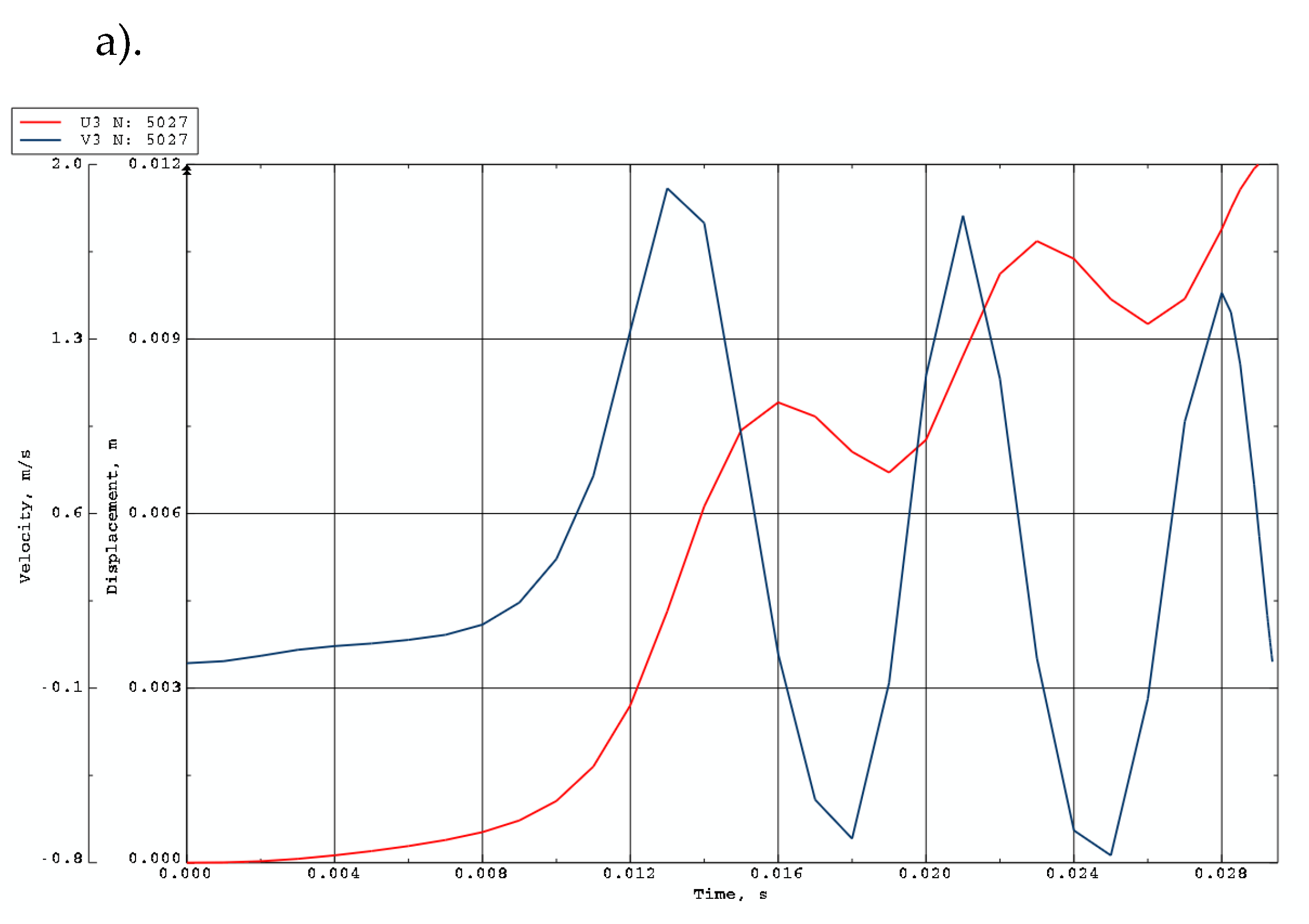

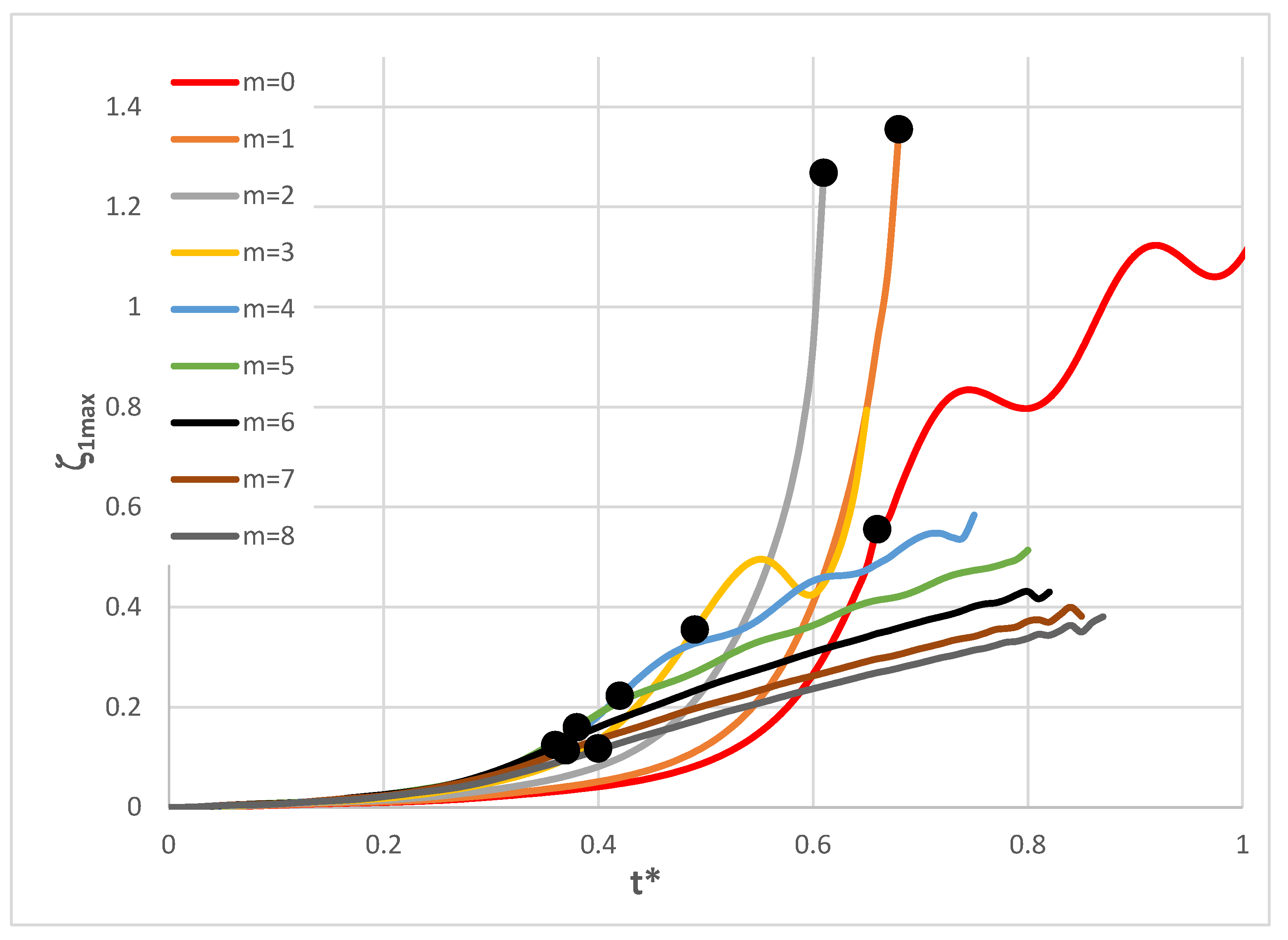

Figure 6.

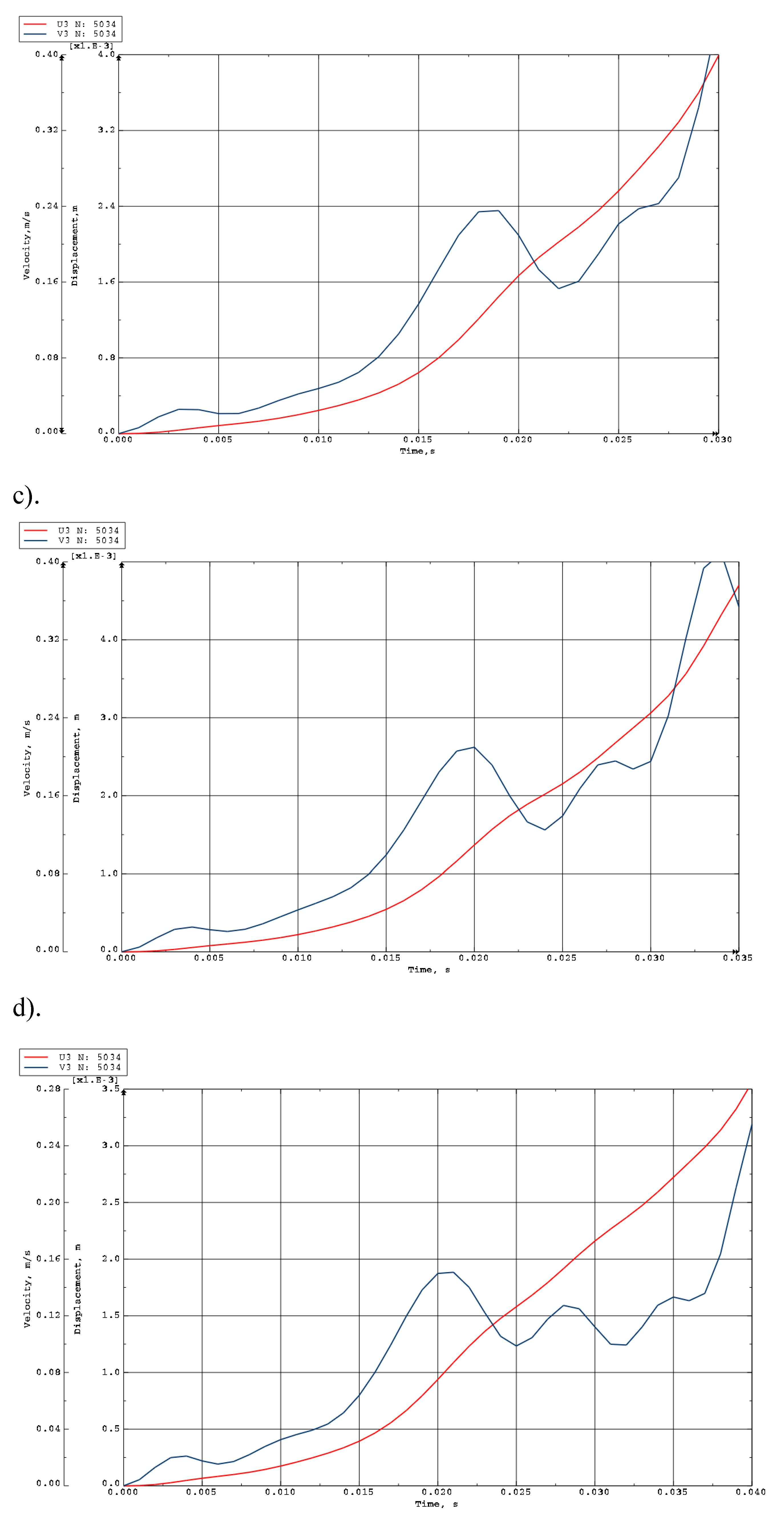

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 0.2.

Figure 6.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 0.2.

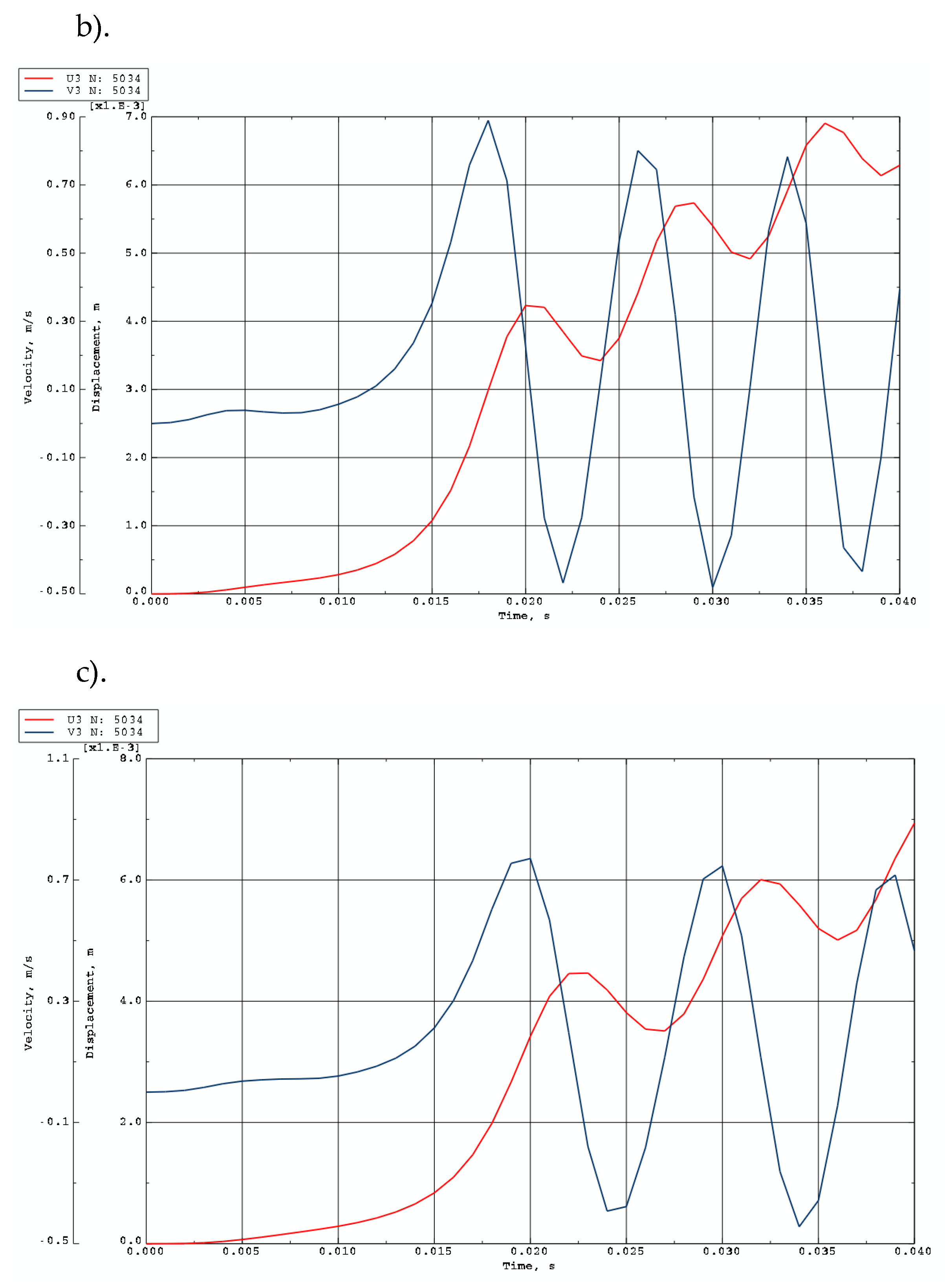

Figure 7.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 1.

Figure 7.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 1.

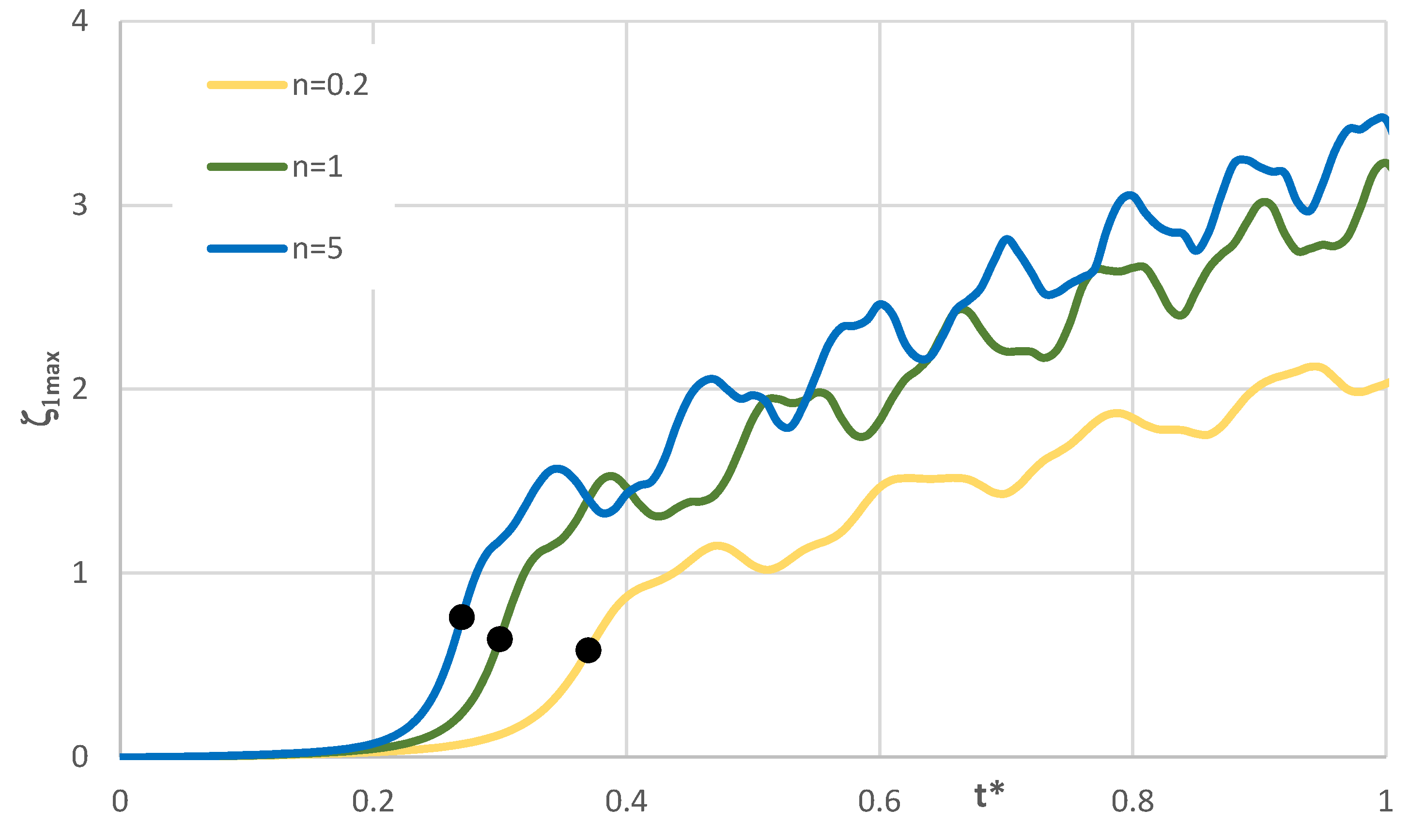

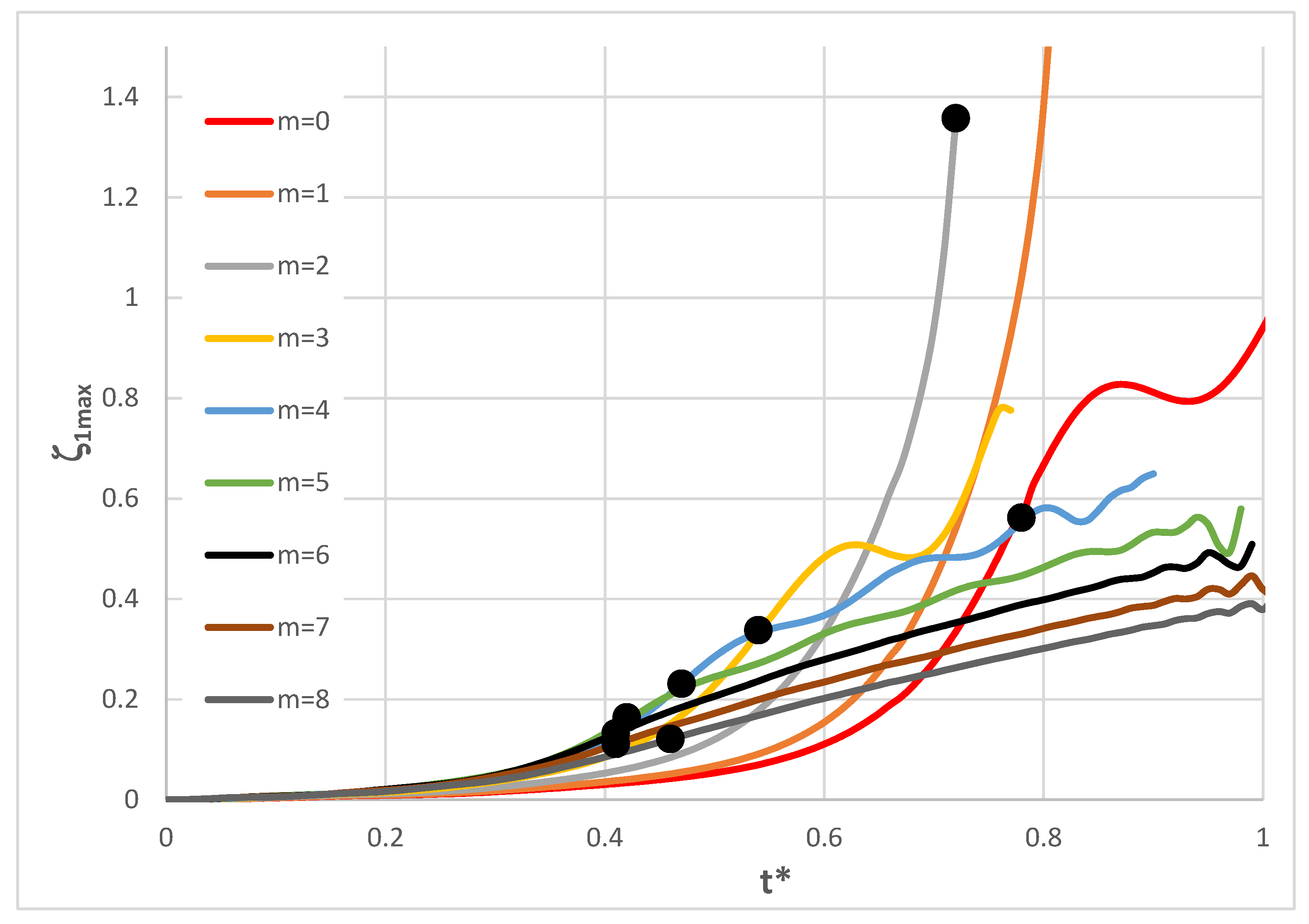

Figure 8.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 5.

Figure 8.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on St-Al plate mode m for n = 5.

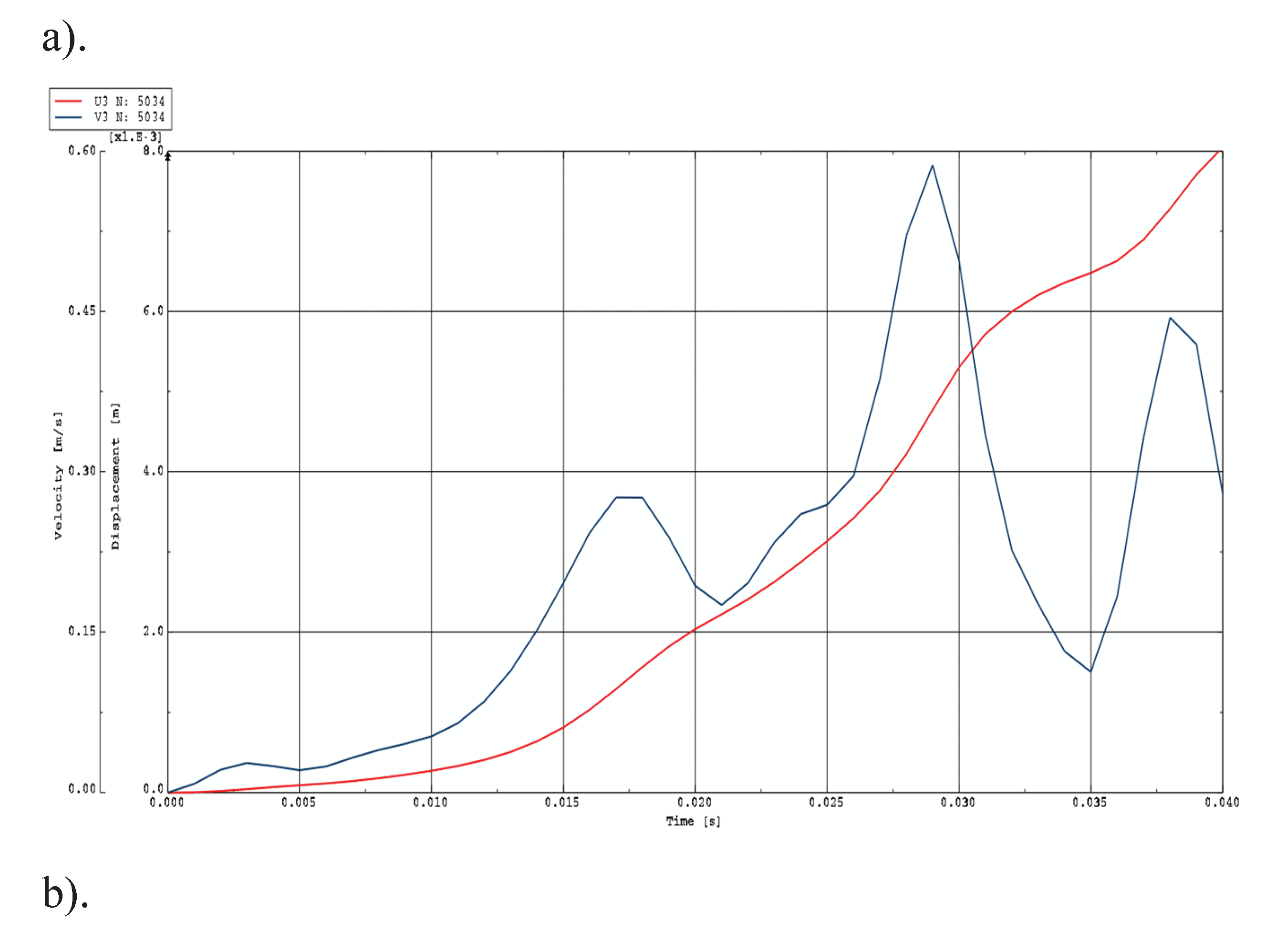

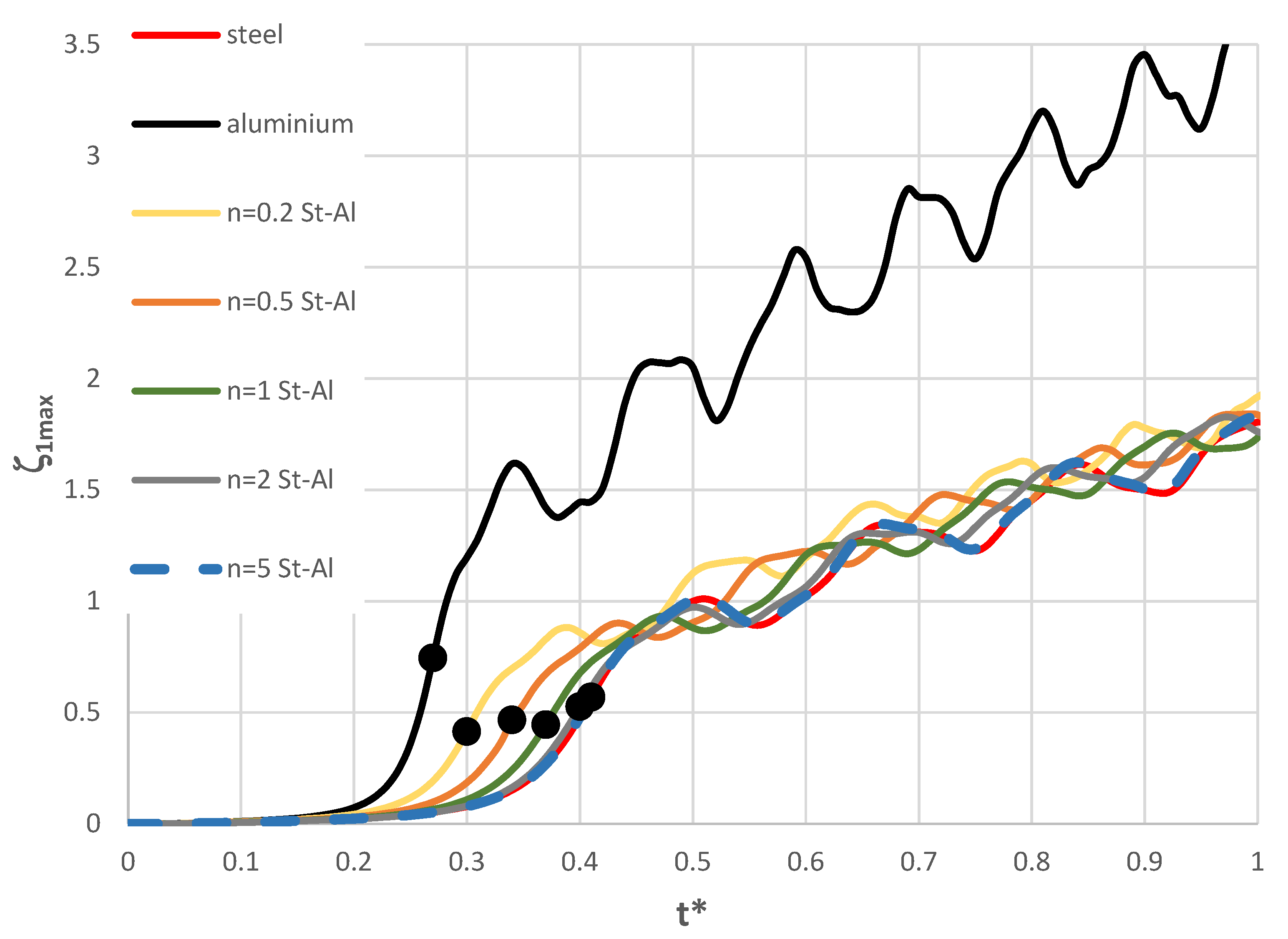

Figure 9.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on steel, aluminium, and St-Al plate models for various power-law exponents n and plate mode m = 0.

Figure 9.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on steel, aluminium, and St-Al plate models for various power-law exponents n and plate mode m = 0.

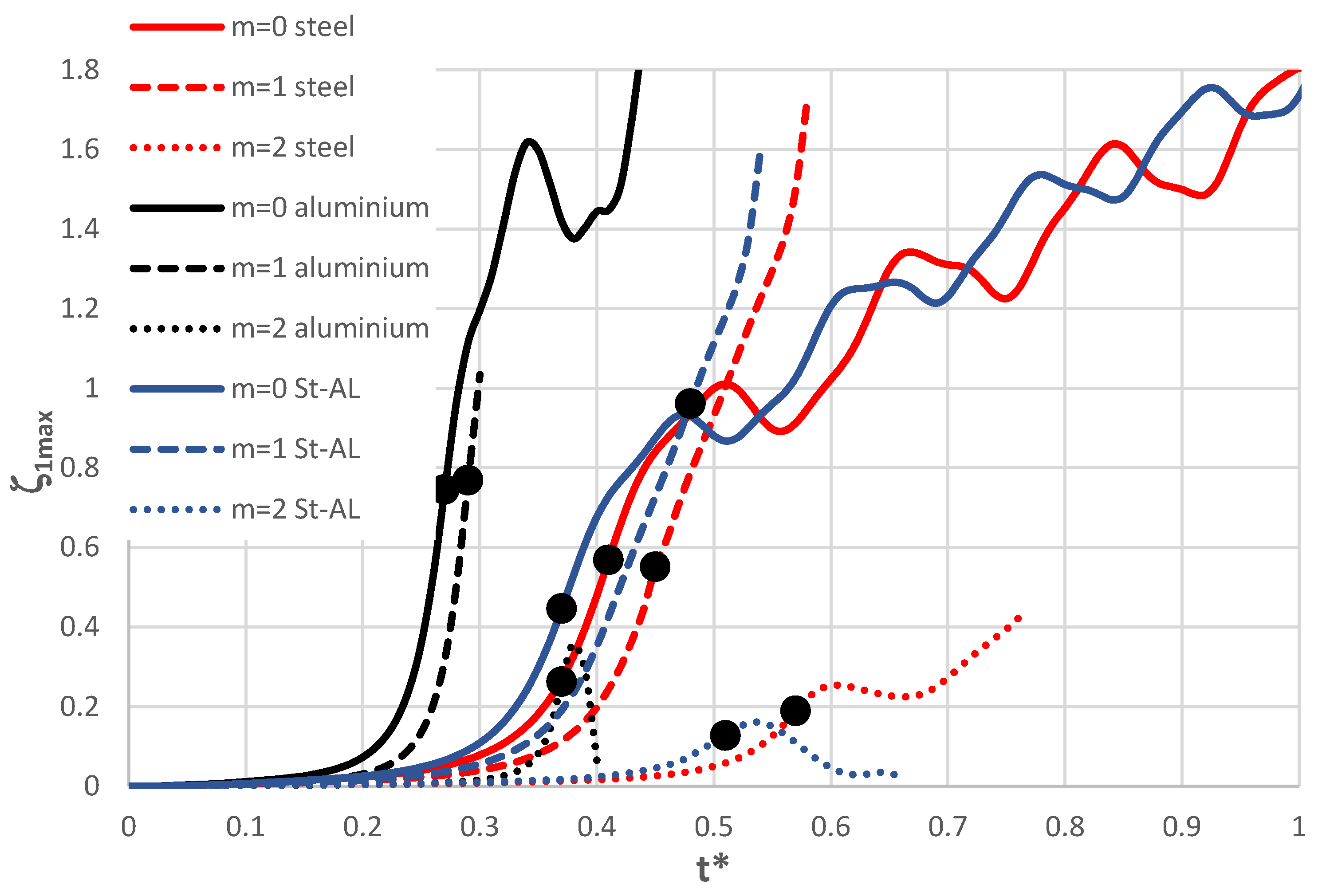

Figure 10.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on steel, aluminium, and St-Al plate models for power-law exponent n = 1 and modes m = 0, 1, 2.

Figure 10.

Time history of dimensionless deflections ζ1max depending on steel, aluminium, and St-Al plate models for power-law exponent n = 1 and modes m = 0, 1, 2.

Table 1.

Geometrical and material plate parameters.

Table 1.

Geometrical and material plate parameters.

| Description |

Parameter |

Value |

| Geometrical parameters |

| plate inner radius |

ri |

0.2 m |

| plate outer radius |

ro |

0.5 m |

| facing thickness |

h’ |

1 mm |

| core thickness |

h2

|

5 mm |

| Material parameters |

| Young’s modulus of steel |

Est |

210 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio of steel |

νst |

0.3 |

| mass density of steel |

µst |

7850 kg/m3

|

| Young’s modulus of aluminium |

Eal |

70 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio of aluminium |

νal |

0.33 |

| mass density of aluminium |

µal |

2700 kg/m3

|

| Kirchhoff’s modulus of polyurethan foam of core material |

Gc |

5 MPa |

| mass density of polyurethan foam of core material |

µc |

64 kg/m3

|

| power-law exponent of the eq. (2) |

n |

0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 |

| Load parameters |

| rate of dynamic loading growth |

s |

1000 MPa/s for plate loaded on the outer edge |

| 5000 MPa/s for plate loaded on the inner edge |

Table 2.

Detailed values of the critical dynamic loads pcrdyn versus mode number m for the St-Al plate model loaded on the outer edge for different values of n and number N of discrete points.

Table 2.

Detailed values of the critical dynamic loads pcrdyn versus mode number m for the St-Al plate model loaded on the outer edge for different values of n and number N of discrete points.

| m |

pcrdyn , MPa |

| St-Al model n=1 |

St-Al model n=5 |

|

N=14 |

N=20 |

N=26 |

N=14 |

N=20 |

N=26 |

| 0 |

32.5 |

32 |

33 |

37.5 |

37.5 |

38 |

| 1 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

40 |

40 |

40 |

| 2 |

30.5 |

30.5 |

30.5 |

36 |

36 |

35 |

| 3 |

24.5 |

24.5 |

24.5 |

26.5 |

27 |

27,5 |

| 4 |

21 |

21 |

21 |

23 |

23 |

23.5 |

| 5 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

21 |

21 |

21 |

| 6 |

18.5 |

18.5 |

18 |

20 |

20 |

20.5 |

| 7 |

18 |

18 |

18.5 |

20.5 |

20.5 |

20.5 |

| 8 |

20.5 |

20.5 |

20 |

23 |

23 |

23 |

Table 3.

Critical dynamic pcrdyn and static pcr loads for the FDM plate model

Table 3.

Critical dynamic pcrdyn and static pcr loads for the FDM plate model

| m |

FDM plate model |

| steel |

aluminium |

St-Al n=0.2 |

St-Al n=1 |

St-Al n=5 |

pcrdyn,

MPa |

pcr, MPa |

pcrdyn, MPa |

pcr, MPa |

pcrdyn, MPa |

pcr, MPa |

pcrdyn, MPa |

pcr, MPa |

pcrdyn, MPa |

pcr, MPa |

| 0 |

37.5 |

33.01 |

29.5 |

24.5 |

29.5 |

25.25 |

33 |

27.88 |

38 |

32.66 |

| 4 |

23.5 |

21.39 |

18.5 |

16.09 |

18.5 |

17.01 |

21 |

18.91 |

23.5 |

21.11 |

| 5 |

21.5 |

20.54 |

17 |

15.27 |

17 |

16.20 |

19 |

18.11 |

21 |

20.24 |

| 6 |

20.5 |

20.48 |

16 |

14.96 |

16.5 |

15.93 |

18 |

17.95 |

20.5 |

20.20 |

| 7 |

21 |

21.06 |

15.5 |

14.97 |

15.5 |

16.02 |

18.5 |

18.22 |

20.5 |

20.74 |