1. Introduction

Meteorites represent a unique opportunity to sample remnants of accretionary products of the early Solar System. Over 50,000 meteorites have been found on Earth. These meteorites are classified into different groups based on their composition and origin: Moon, Mars, or asteroids They can further be divided into groups, sub-groups, clans, etc. [

1,

3].

Because of their huge numbers, diversity and complexity, there are several ways to classify them. The most common and simple classification method, divides them into three main groups: (i) stony meteorites, with metal content (generally Fe-Ni-Co alloys) less or equal to 30 wt.% (ii) stony-iron meteorites with about 50–65 wt.% of metal materials and Fe-Ni-Co alloys, and (iii) iron meteorites, their Fe-Ni-Co alloys content is high up to 95 wt.%. Each group can be further divided into sub-groups based on their composition and formation history. Another classification method divides the meteorites as: differentiated (which contain all three groups) and undifferentiated which are the stony meteorites only. The basic properties of the three main groups are as follows.

(a) The stony meteorites can be divided into: (a) Chondrites, who are the most common (91.5%) meteorites and (b) Achondrites. (a) The chondrites are considered to be among the oldest rocks in our solar system, dating back to the formation of the planets. They are characterized by the presence of chondrules (small, spherical inclusions of silicate melt droplets) and mineral compositions that reflects the early solar system. Ordinary chondrites are by far the most numerous groups and based on their iron content, they are further divided into three sub-groups: H (25–28 wt.%), L(20–25 wt.%) and LL(19–22 wt.%). (b) The Achondrites meteorites [originated from “chondrules” which are the spherical millimeter-sized silicate aggregates] are similar to terrestrial rocks and are formed from melted and differentiated materials, like those found on planets or large asteroids. Some of them are classified as "primitive achondrites" -from Moon, or "planetary achondrites", from -Mars.

(b) Iron Meteorites are dominantly composed of various phases of Fe-Ni-Co alloys which originated from molten or solidified core of the parent bodies. They may contain small inclusions such as troilite (FeS), schreibersite (Fe,Ni)3P, silicates, etc. Their magnetic transition temperatures (TC) are well above room temperature (RT).

(c) The Stony-Iron Meteorites are mixtures of metallic Fe-Ni-Co alloys and silicate minerals mainly olivine (Mg,Fe)SiO4). There are two main subgroups: Pallasites: where the silicate crystals are embedded in the metallic matrix and Mesosiderites: where the silicates are mixed with the metallic materials.

Over the past decades, our group has conducted large-scale research on various meteorites, which includes their characterization by: optical microscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), magnetization measurements and especially by

57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy (MS). These studies were published in more than 30 scientific papers (see, e.g., ([

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and references therein]). Most of them were published in specific journals on meteoritics, earth sciences or geochemistry. These publications demonstrated: characterization, magnetic and approaches for classifications of meteorites. This manuscript (which is not a review one) is intended for an average scientist who is not exposed to magnetism of meteorites.

Practically, meteorites are usually named after the places in the world where they fell. In most cases, at room temperature (RT), the iron-based alloys are soft ferromagnetic (FM) (with small hysteresis loops), and their magnetic transition temperatures (Tc) are at elevated temperatures. All meteorites are not homogeneous multi-phase materials. Therefore, the magnetic results made on the same meteorite may be slightly different when measured in its different areas. Indeed, in several cases, the interior and the fusion crust of the same meteorite showed some differences in their physical and magnetic properties. Therefore, comparing magnetic results made in one laboratory with data published by others, may be misleading.

We will focus here, on seven different meteoritic samples (presenting the three different groups mentioned above) with the purpose of showing the diversity of their magnetic properties. Those who are interested in other extended measured properties should refer to our published corresponding articles. All results presented here have already been published by us in the past.

2. Materials and Methods

The meteorites powders (except troilite) were obtained from the polished sections of various meteorite fragments, by the Institute of Physics and Technology, Ural Federal University (Ekaterinburg, Russian Federation). These powders were also used for XRD, EDS, MS and for other characteristics studies [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Magnetic measurements on powder meteorites (mounted in gel-caps), were carried out with a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer (Quantum Design, Inc.) at the Racah Institute of Physics, the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. The differential SQUID sensitivity is 10–7 emu with an uncertainty of 1%. The zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) temperature dependent magnetization M(T) branches, via heating, were measured in the range of 5–300 K under low applied magnetic fields (H). The samples were cooled to 5 K at H=0, then H was applied to trace the ZFC branch. Under this H, the FC branch was measured via warming from 5 to 300 K. The field dependence of isothermal magnetization M(H) curves was measured under H range, of 50 kOe to –50 kOe.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stony Meteorites

For this group, one undifferentiated (Bjurböle) and one differentiated (Sariçiçek) meteorites were chosen, Extended studies of these meteorites including: optical microscopy, SEM with EDS, XRD and MS were published in [

7,

8].

3.1.1. Chondrite Bjurböle L/LL4 Ordinary Chondrite

On March 12, 1899, 328 kg of meteorite fell near Bjurböle, Finland and was classified as L/LL4 ordinary chondrite. [22 ordinary chondrites only were classified as L/LL4]. Bjurböle meteorite has visible chondrules which contain: homogeneous olivine (Fe,Mg)

2SiO

4, orthopyroxene (Fe,Mg)SiO

3, troilite (FeS) and pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS), chromite (FeCr2O

4), hercynite (FeTiO

3) and α γ-FM Fe(Ni,Co) phase [

7].

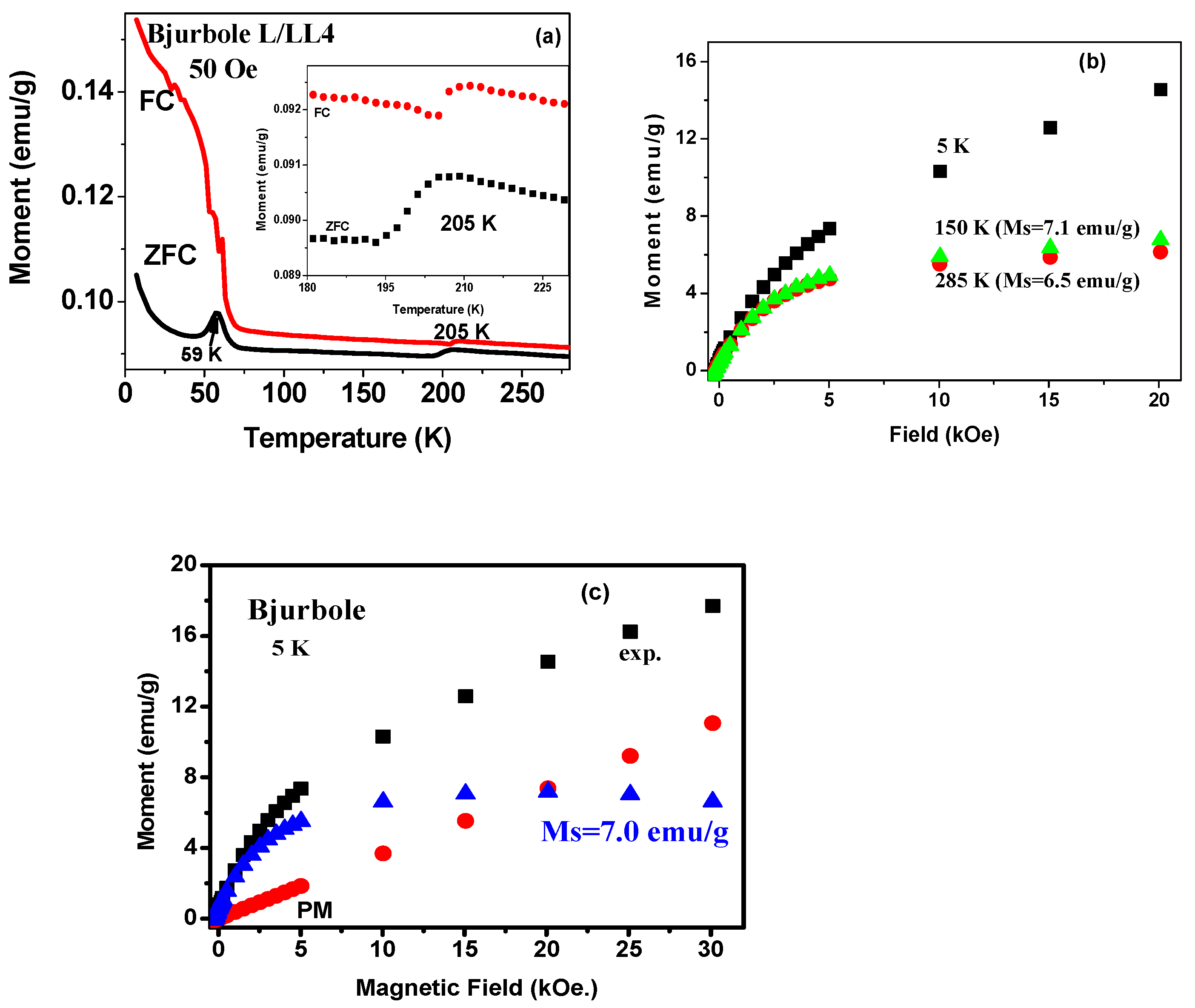

The ZFC and FC magnetization

M(

T) curves of bulk interior Bjurböle measured at 50 Oe and the isothermal

M(

H) plots at 5 and 295 K are displayed in

Figure 1(a ,b). Both ZFC and FC plots indicate a multi-phase magnetic material. A pronounced peak in ZFC and small bump in FC plots at 57(1) K and small steps around 205(2) K in both branches, are readily observed. The two curves do not merge at RT, indicating a small magnetically ordered phase with

TC above RT. At low temperatures, the sharp increase (in particular in the ZFC branch) marks the presence of paramagnetic (PM) component(s). The peak at

T ~ 57 K is related to the magnetic phase transition of chromite [

13] and were found in other LL meteorites as well [

14]. Another option is that this peak originated from solidified of oxygen absorbed on the meteorite powder surface [

15], as observed in several other powder based material.[

16,

17]. The origin of the step around 207(2) K is not known yet. A similar bulge at ~201 K, was observed in the FC curve of bulk interior of Kemer L4 [

18].

At low temperatures (5-47 K), the ZFC branch adheres closely to the PM Curie-Weiss (CW) law:

where

χ0 is the temperature independent part of the susceptibility,

C is the Curie constant,

T is the measured temperature, and θ

CW is the CW temperature. Due to the multi-phase material, the deduced relevant parameter is: θ

CW = –3.0 (0.1) K, indicating weak anti-ferromagnetic (AFM) interactions at low temperatures.

In all Isothermal

M(

H) curves (

Figure 1,b.), the magnetization first increases linearly up to 5 kOe and then tends to saturate. The absence of saturation reveals an admixture of magnetic and PM components. The experimental

M(

H)

exp plots can be fitted as:

where

MS is the saturation magnetic moment of the FM component and χ

pH is the linear PM contribution (blue red stars in

Figure 1,c respectively). The values deduced at 5 K are:

MS = 7.0(1) emu/g and

χp = 3.7(1) × 10

–4 emu/g Oe. At 150 K and 295 K the PM contributions are low and

MS = 7.1(1) and 6.4(1) emu/g respectively, indicating FM phase(s) with high

TC value. All

M(

H) plots show small hysteresis loops (not shown) with

HC = –200(10) and –160(10) Oe at 5 and 150 - 285 K, respectively. (see

Figure 5 below)

The

MS values obtained here agree well with

MS = 5.42 and 8.8 emu/g obtained for similar ordinary chondrites meteorites: NWA 6286 LL5 and NWA 7857 LL5 [

19], and in line with the general statement that for LL ordinary chondrites, the

MS value arearound 10 emu/g [

20].

3.1.2. Achondrite Sariçiçek Howardite

Sariçiçek is an Achondrite meteorite that fell in Turkey on September 2015. Beside troilite, chromite, hercynite and Fe-Ni-Co alloy, it is rich with orthopyroxene (Fe,Mg)SiO

3 and clinopyroxene (Fe,Ca,Mg)SiO

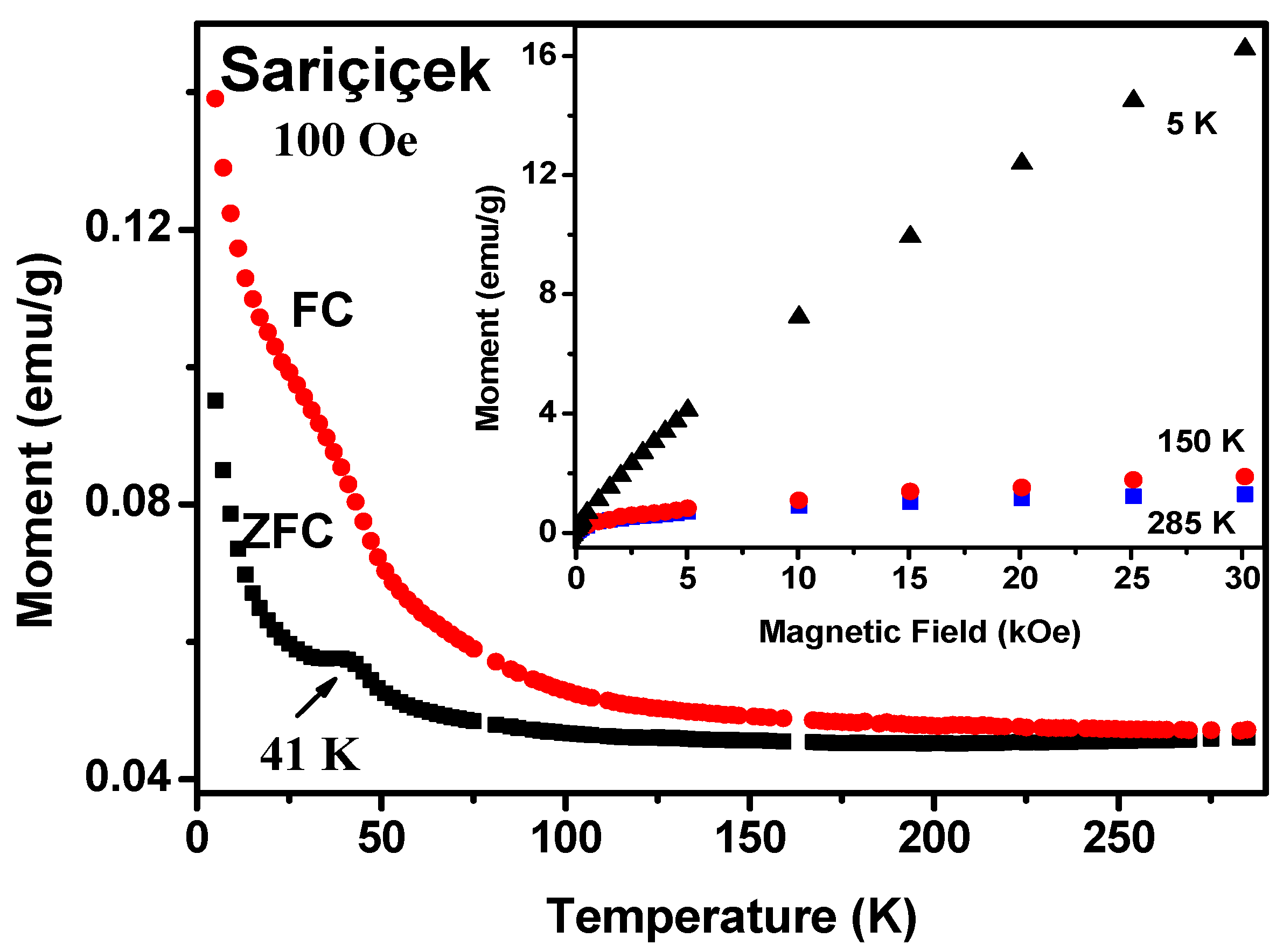

3. We studied its bulk interior and its fusion crust magnetic properties which were quite similar to each other. For the sake of brevity, we show in

Figure 2 the magnetic data of the fusion crust part only [

8].

In fact,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 are very similar to each other. The two ZFC and FC curves of the fusion crust, show dominant PM contribution. As above, the ZFC branches show

s a clear peak at ~ 41 K for the fusion crust or 40 K for interior, which are related to the ferrimagnetic-PM phase transition of chromate . At higher temperatures the PM curve obeys the CW law (equation 1) and the deduced positive θ

CW =25.7(1) or -7.6 K for the fusion crust or interior respectively. The higher value of θ

CW indicates an increase of the dominant interactions in the PM phases in Sariçiçek. Here again, the ZFC and FC curves approaching each other but do not merge up to RT.

The 5 K

M(

H) plots of Sariçiçek fusion crust (

Figure 2 ,inset) demonstrate an admixture of magnetic and dominant PM components and can be fitted by equation 2 and the deduced

MS values is 3.9(1) emu/g (12.7(1) emu/g for the interior) indicating a lower value for fusion crust . For 150 and 185 K, Ms=1.9(1) and 1.3(1) respectively That is consistent with the low Ms values obtained for Bjurböle and other stony meteorites [

20].

3.2. Iron Meteorites

Three proto-type samples of iron meteorites from different subgroups were chosen here: (1) Mundrabilla IAB-ung (medium octahedrite), (2) Sikhote-Alin IIAB (coarsest octahedrite) and its troilite inclusion and (3)Trenton IIIAB (medium octahedrite). Detailed studies of these samples by optical microscopy, SEM with EDS, XRD and Mössbauer spectroscopy have been recently carried out by us (see [

9,

10]).

3.2.1. Mundrabilla IAB-ung Iron Meteorite

Two massive fragments of 10–12 and 5.5 tons and many smaller fragments of meteorite shower were found near- Mundrabilla, Western Australia in 1966 and 1979. Mundrabilla is classified as IAB-ung (ungrouped) iron meteorite. IAB-ung IAB-ung classification means, meteorites composed of iron and silicate inclusions which cannot be classified with any known meteorite subgroups class. It is composed of several magnetic Fe-Ni-Co phases, troilite, graphite, schreibersite (Fe,Ni)3P, daubréelite (FeCr2S4), chromite and silicate inclusions.

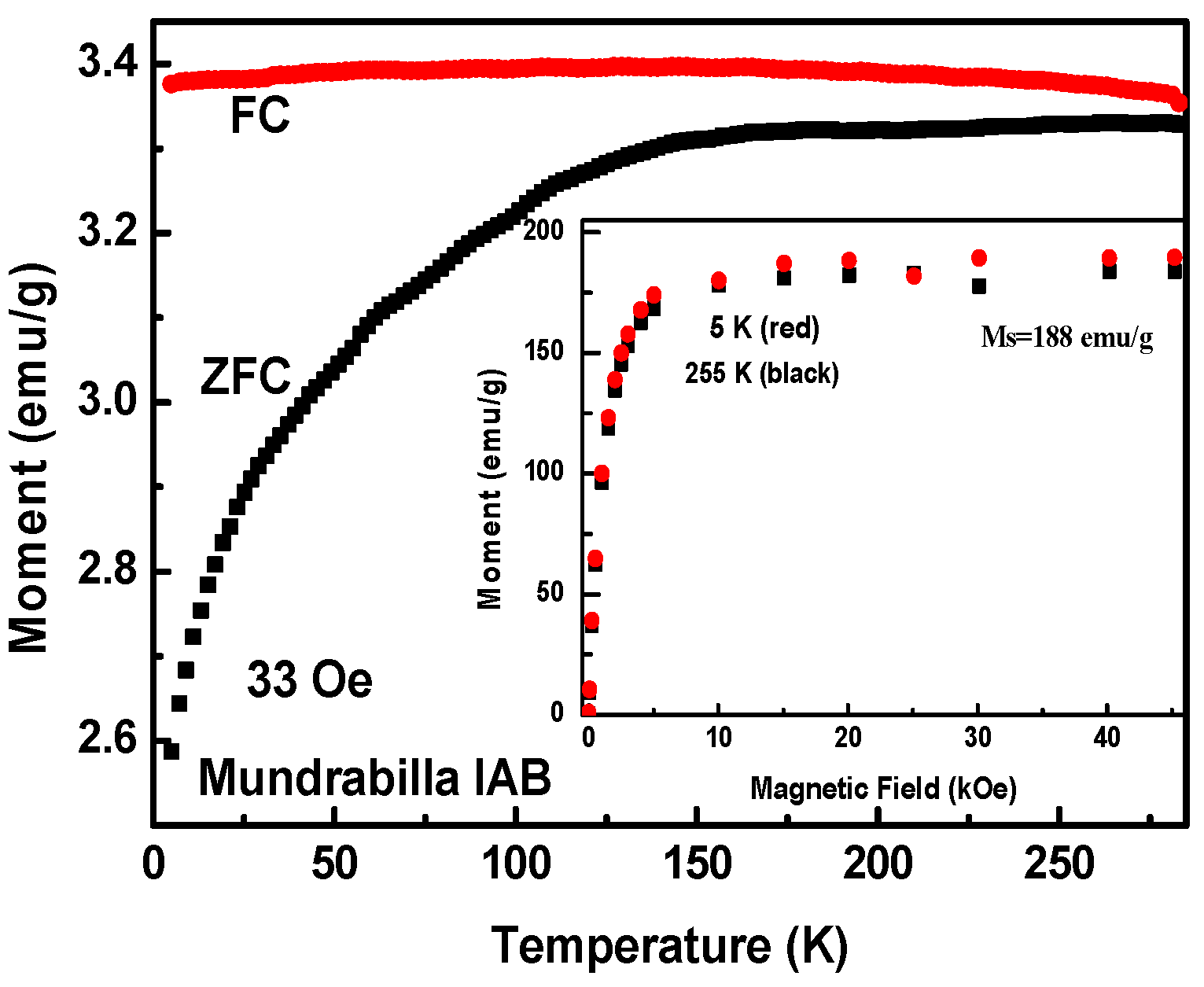

Mundrabilla consists of several magnetic phases and both

M(

T) and

M(

H) plots (

Figure 3) exhibit their macroscopic FM bulk behavior. Here, the magnetic moments values, are 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than shown above for stony meteorites (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The ZFC plot increases slightly (around 20% only) from 5 K to RT and the last RT measured moment value remains unchanged in the almost a straight line of FC branch. That is a typical behavior of FM materials with

TC well above RT. Due its high magnetic moment, the peak in the ZFC branch around 50 K related either to chromite or to oxygen solidification, is not visible.

The two

M(

H) curves at 5 and 255 K (

Figure 3, inset) practically are the same. Full saturation is already achieved around 7–8 kOe. and

MS = 188(2) emu/g for both temperatures are lower by 15% only, than 220 emu/g reported for pure iron at RT. This high

MS indicates the high

TC of the various phases in Mundrabilla IAB-ung.[

9] No hysteresis loops were observed in both curves.

3.2.2. Sikhote-Alin IIAB Iron Meteorite and Its Troilite Inclusion

A second iron meteorite example, is Sikhote-Alin IIAB. which fell as the largest meteorite shower, on 1947 in Eastern Siberia (Russia) near Sikhote-Alin mountains. The main phase of bulk Sikhote-Alin is the α-Fe-Ni-Co with approximately metal composition of: Fe (93%) , Ni(5.9%) , Co(0.42%) and other tiny trace elements. Optical microscopy, XRD and SEM with EDS studies showed that this bulk, contains minor iron bearing inclusions of phosphides and sulfides. The inclusions consist of slightly iron deficient (0.014) troilite (FeS) (~93% wt.%) and (~7 wt.%) daubréelite FeCr

2S

4 without any Fe-Ni-Co alloy phase [

21,

22]. Here we show the magnetic studies of:(i) the main bulk Sikhote-Alin phase and (ii) its extracted massive troilite inclusion.

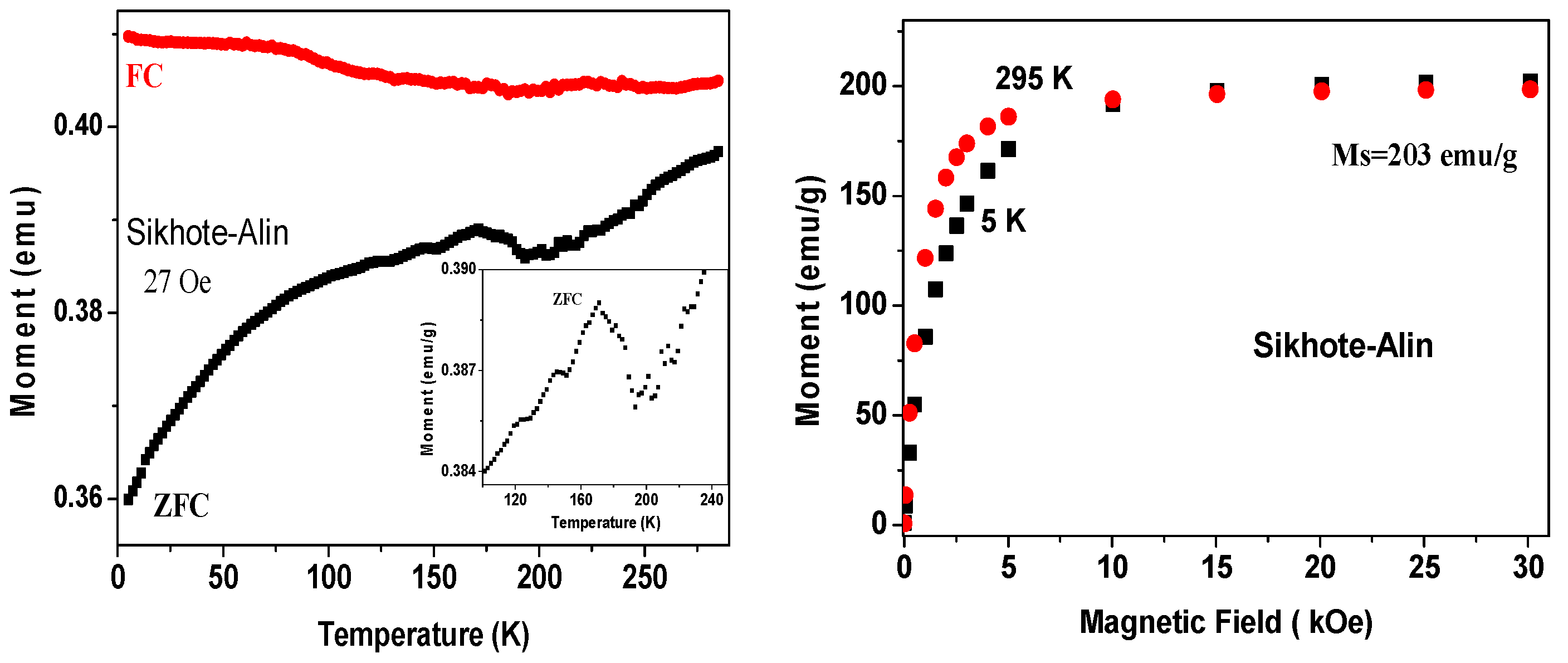

(i) The

M(

T) and

M(

H) plots for bulk Sikhote-Alin IIAB are shown in

Figure 4 . Similar to Mundrabilla (

Figure 3) no bifurcation in the ZFC and FC is observed at RT. However, due to the multi-phase magnetic phases, the ZFC branch exhibits several discontinuities (inset) in the temperature range of 160–230 K, their explanation is debatable. The

M(

H) curves at 5 and 295 K (

Figure 4, right), which overlap at high H values, clearly indicate the presence of dominant FM phase(s) with

MS = 203 emu/g, a value which is slightly higher than 183 emu/g obtained for Mundrabilla IAB-ung (

Figure 3).

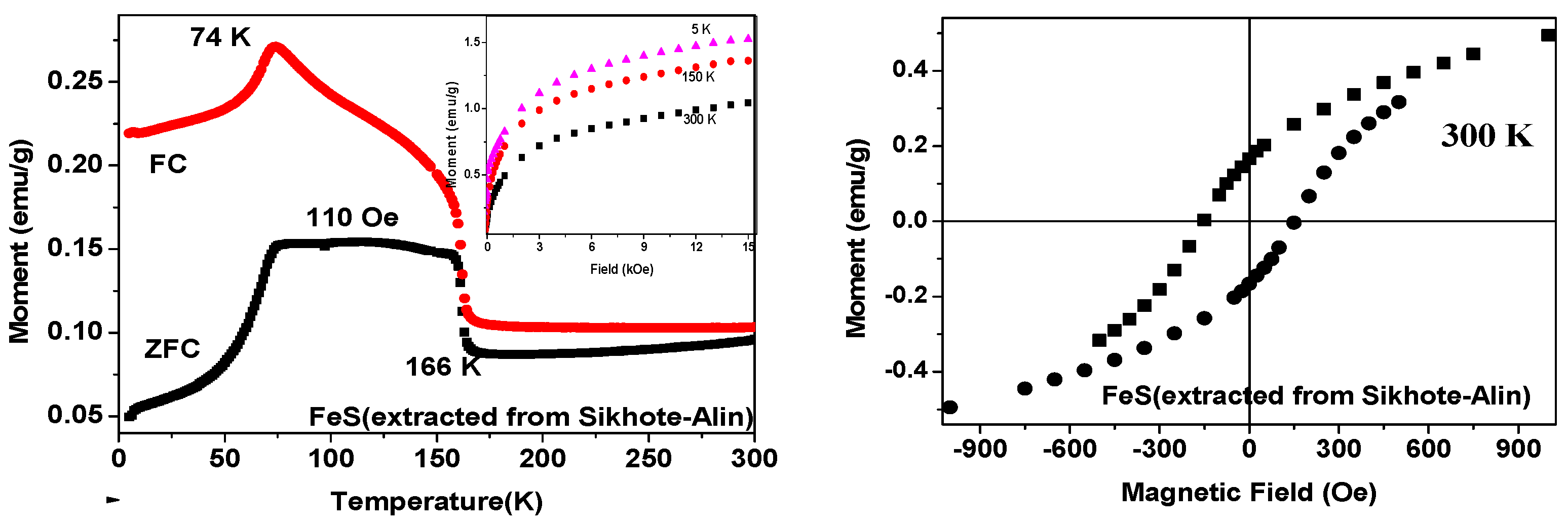

(ii) The magnetization

M(

T) and

M(

H) plots for the troilite

inclusion are shown in

Figure 5. The ZFC and FC curves (left) measured at 110 Oe do not merge at RT. They display a distinguished transition at 74(1) K and a sharp magnetic decrease at 166(2) K. These magnetic transitions are explained as follows. Troilite is primarily AFM ordered and undergoes around 70 K a magnetic transition to a canted AFM regime up to its magnetic transition

TN, around 588 K. [

23]. On the other hand, pure FeCr

2S

4 is ferrimagnetically ordered with Tc ~177 K which is presented here as the transition at 166 K.

The isothermal

M(

H) curves measured at 5, 150 and 300 K (

Figure 5, inset) treated by Equation 2 yield

MS = 1.01, 1.17 and 0.74 emu/g respectively. These small M

S values are due to the presence of a tiny magnetic phase with high Tc. A small hysteresis loop with a coercive field

HC of 150(5) Oe is observed at 300 K (

Figure 5 right). The hysteresis observed here (and also in

Bjurböle as discussed above), appears only when the measured M(T) curves are low and as a result, the Ms values are around 1-4 emu/g. In bulk iron meteorite the hysteresis loops are masked by the high M(T) values where Ms=180-240 emu/g.

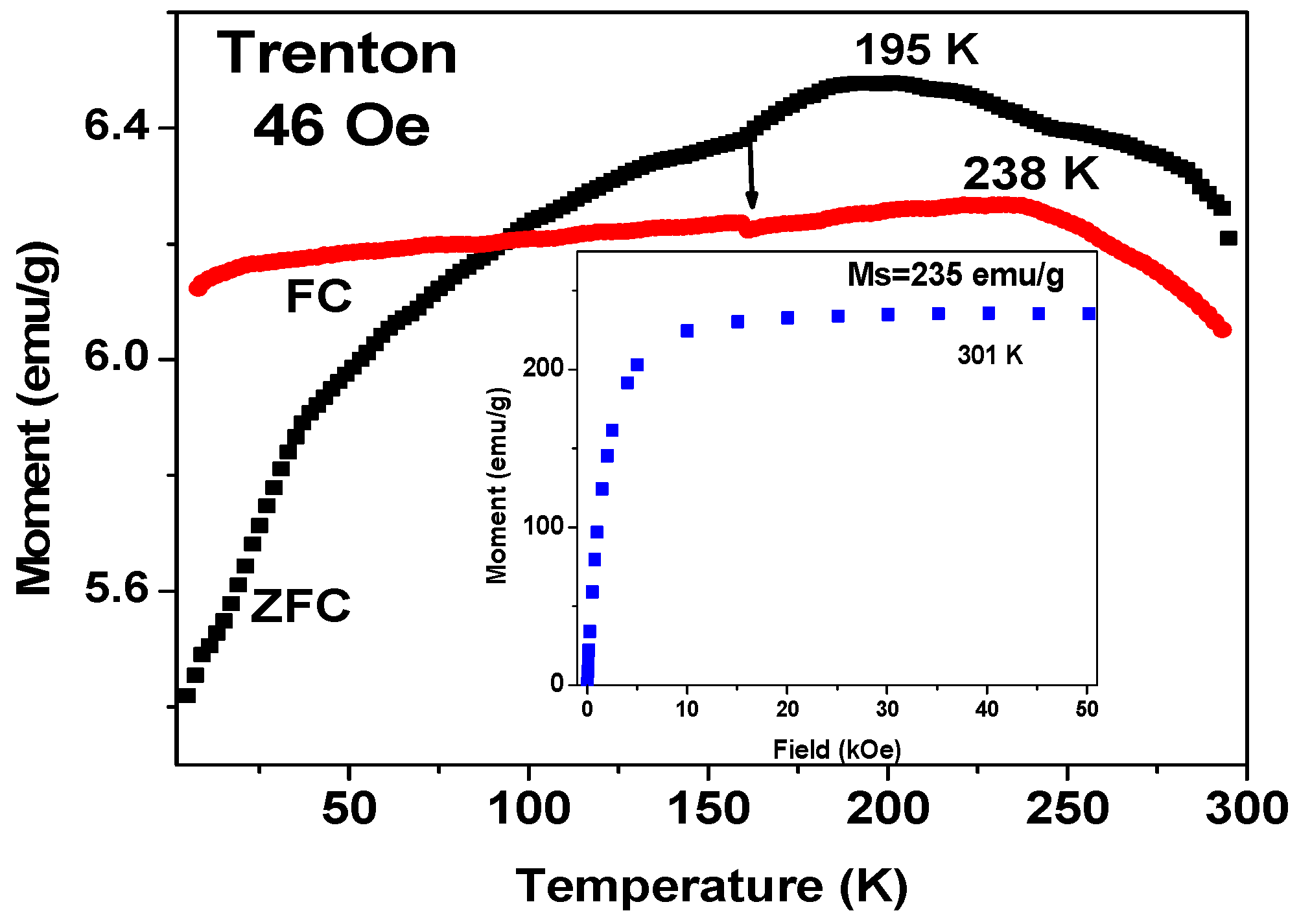

3.2.3. Trenton IIIAB Iron Meteorite

This iron meteorite, found in 1868 in Trenton, Wisconsin (USA), was classified as an iron, IIIAB octahedrite. (IIIAB group, signify a specific range of nickel and other elements concentration). Trenton is characterized by its medium visible octahedrite structure and also contains inclusions. However, its M(T) (shown in

Figure 6) are quite different from the two iron meteorites presented above.

Typically to other iron meteorites the ZFC plot first increases with temperature up to 195 K and then slightly decrease up to RT. Here again, the FC branch reflects the last measured ZFC moment (the moment at 5 K is smaller by 2% than the ZFC value at RT). Un expectedly, at 95 K the ZFC curve cuts the FC branch, thus ZFC>FC. Within the uncertainties the whole ZFC > FC effect is around 3%. (At 195 K, M

ZFC and M

FC are 6.46 and 6.26 emu/g respectively). This is a peculiar rare phenomenon which was seldom observed 16-17]. In addition, in both Campo del Cielo IAB and Gebel Kamil ung iron meteorites, the ZFC>FC phenomenon obtained in the entire temperatures range 5-300 K [

10].

This peculiar ZFC>FC behavior was observed and explained in: (i) amorphous carbon [

16], (ii) multi-layered of Ni or Co chiral-based magnetic memory devices and in (iii) some human liver tissues [

17]. These cases are somewhat different than the phenomenon shown for Trenton. There (a) the pronounced narrow ZFC peaks cut the FC branchs, twice, say, around 40-50 K and 70-80 K, thus ZFC>FC ranges are limited to 20-30 K only. (b) The materials are basically diamagnetic with a very low background. Although these differences, we propose that the hand-waiving model applied there [

16,

17], may also be valid here (

Figure 6). The rapid solidification process of Trenton generated a minor fraction of un-oriented intrinsic magnetic domains (or spins) which were randomly distributed over the meteorite matrix, without contributing to the total magnetic moment. During the ZFC process, at a certain temperature, the applied H orients this un-oriented fraction to be in the field direction, causing an extra M(T) moment in the ZFC branch, which exceeds the FC branch. Then, it is expected that above RT before they merge at Tc, the ZFC curve should decrease and cut (or merge) the FC one.

The RT isothermal

M(

H) curve of Trenton IIIAB is shown in

Figure 6 inset. No hysteresis loop is observed. Similar to other iron meteorites, the

M(

H) shape clearly indicates the presence of dominant FM phase(s) with high

MS = 235 emu/g. This relatively high

MS is related mainly to the high content of various Fe-Ni-Co phases. Similar high

MS values 241(2) and 238(3) emu/g, were deduced for Campo del Cielo IAB iron meteorite and for Fe-Ni-Co alloy extracted from Omolon PMG stony-iron meteorite: respectively [

11] These

MS values are higher by 5–10% than

MS = 220 emu/g of pure iron (or 170 emu/g for Co) at RT. Similar

MS = 232 emu/g at RT, was observed for equi-atomic Fe-Co alloy [

24].

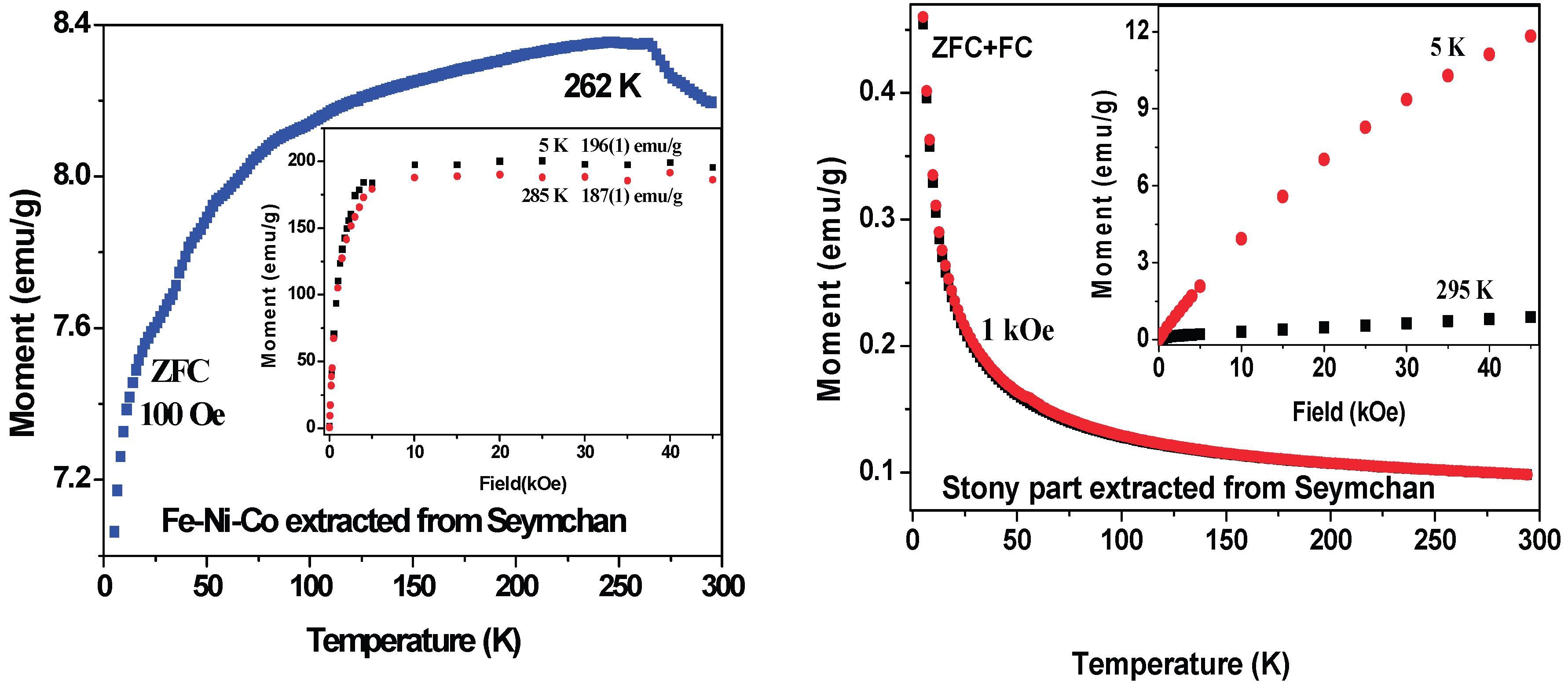

3.3. Stony-Iron Meteorites

Seymchan, found in Magadan (Russia), was classified as a stony-iron pallasite class meteorite. Pallasite (which are relatively rare) were formed by slow cooling of solid silicate mixtures such as: olivine (Fe,Mg)

2SiO

4) and pyroxene (Fe,Mg,Ca)SiO3 (stony), embedded in molten Fe-Ni-Co iron based core. They may also contain some troilite (FeS) and chromite (FeCr2O

4) [

11].

We managed to depart between the stony and the iron core parts of Seymchan and measure them separately. Similar to

stony meteorites (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), the stony part (

Figure 7 right) is PM at all 5-300 K temperature range, The ZFC and FC curves coincide and adhere to the CW (Eq. 1). The deduced parameters are: C =0.00034(1) emu/g.Oe, and θ

CW=-4.7(2) K, indicating weak AFM interactions at low temperatures, as discussed for Bjurböle stony meteorite (

Figure 1). The M(H) curves measured at 5 and 295 K (inset) exhibit typical PM behavior. On the other hand, for the molten Fe-Ni-Co core the ZFC curve (

Figure 7, left) increases with temperature up to 262 K and for M(H) at 5 and 285 K, Ms =196(1) and 187(1) emu/g respectively were deduced, consistent with other iron meteorites (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 6)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Meteorites are important materials for magnetic investigations, due to their unique structures formed in the extreme space conditions, which cannot be reproduced at Earth. Over the past few years, we have extensively studied dozens of different meteorites and display here, the magnetic behavior only, of seven representing examples. This article is directed to non-expert scientists in meteorites, therefore, we used here the common meteorites classification to three main groups: stony, iron and stony-iron meteorites. In general, all meteorites are not homogeneous. Therefore, data obtained from one part of a matter (say its interior) can be slightly different from that measured in its crust.

Practically, all three groups are composed of two fractions: (i) the high Tc (well above RT) FM components, mainly based on Fe-Ni-Co alloys, (ii) various inorganic minerals such as: silicates, troilite, chromite etc. which may show either PM behavior or low temperature magnetic transitions. In fact, the difference between the three main groups is, the ratio between these two fractions. The iron-based fraction is the dominant magnetic one and may even mask and overshadow the magnetic properties of the second part, as observed in some iron meteorite main group.

In the

iron meteorite group, we have presented the M(T) (ZFC and FC) curves and the M(H) plots of Mundrabilla and Sikhote-Alin meteorites (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), keeping in mind that all iron meteorites, show similar magnetic behavior. At low applied fields, the measured M(T) magnetic moments values are a few emu/g. The M(H) plots saturate already at 5-8 kOe and all Ms values are high (180-240 emu/g). As an exception, Trenton (

Figure 6) shows the ZFC>FC rare phenomenon above 95 K.

On the other hand, in both

stony and

stony iron meteorites, the PM parts dominate (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 7). The measured M(T) magnetic moment values are relatively low -around 0.1 emu/g. Therefore, magnetic transitions at low temperatures (40-60 K) are visible. Their origin can be partially identified, and may be related to chromite (in its various compositions), or to oxygen solidification. In the PM regions the M(T) curves are fitted by the CW law (Eq. 1). However, since the exact compositions of the PM components were not well determined, the only valid parameter deduced is θ

CW which may reflect the low temperatures magnetic interactions, provided that these PM compounds are symmetric. In Bjurböle and Sarıçiçek stony meteorites, the ZFC and FC branches do not merge at RT and the M(H) plots are composed of PM and FM components and analyzed according to Eq. 2. The extracted Ms values (below 10 emu/g) are an ordered of magnitude lower than Ms values of iron meteorites. This is a clear indication for the tiny FM phases in the stony meteorites. In the stony-iron Seymchan meteorite (

Figure 7), the extracted stony part, is PM in all measured temperature range.

The Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite (

Figure 5) consists inclusions which contain: AFM troilite (FeS 93%) and daubréelite (FeCr2S

4). Tin both ZFC and FC branches we observe first, the reorientation of troilite (at 75 K) and then ferrimagnetic transition of daubréelite (at 166 K). Due to the low M(T) values (Ms = 0.74 emu/g) the hysteresis loop at RT is visible.

Author Contributions

Magnetic measurements and text writing, I.F, editing and comments M.I.O. The authors agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, project № FEUZ-2023-0013.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be provided by requesting via the corresponding email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wasson J.T. Meteorites. Classification and Properties, Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 1974; pp. 1–320.

- Weisberg M.K., McCoy T.J., Krot A.N. Systematics and evaluation of meteorite classification. In Meteorites and the Early Solar System II, Lauretta D.S., McSween H.Y., Jr., Eds.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, USA, 2006; pp. 19–52.

- Maksimova A.A., Oshtrakh M.I. Applications of Mössbauer spectroscopy in meteoritical and planetary science, Part I: Undifferentiated meteorites. Minerals, 2021, 11, 612.

- Maksimova A.A., Oshtrakh M.I. Applications of Mössbauer spectroscopy in meteoritical and planetary science, Part I: undifferentiated meteorites. Minerals, 2021, 11, 612.

- Goryunov M.V., Maksimova A.A., Oshtrakh M.I. Advances in analysis of the Fe-Ni-Co alloy and iron-bearing minerals in meteorites by Mössbauer spectroscopy with a high velocity resolution. Minerals, 2023, 13, 1126.

- Maksimova A.A., Goryunov M.V., Oshtrakh M.I. Applications of Mössbauer spectroscopy in meteoritical and planetary science, Part II: differentiated meteorites, Moon and Mars. Minerals, 2021, 11, 614.

- Maksimova A.A., Petrova E.V., Chukin A.V., Nogueira B.A., Fausto R., Szabó Á., Dankházi Z., Felner I., Gritsevich M., Kohout T., Kuzmann E., Homonnay Z., Oshtrakh M.I. Bjurböle L/LL4 ordinary chondrite properties studied by Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A: Molec. and Biomolec. Spectroscopy, 2021, 248, 119196.

- Maksimova A.A., Unsalan O., Chukin A.V., Karabanalov M.S., Jenniskens P., Felner I., Semionkin V.A., Oshtrakh M.I. The interior and the fusion crust in Sariçiçek howardite: study using X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A: Molec. and Biomolec. Spectroscopy, 2020, 228, 117819.

- Goryunov M.V., Varga G., Dankházi Z., Chukin A.V., Felner I., Kuzmann E., Grokhovsky V.I., Homonnay Z., Oshtrakh M.I. Characterization of iron meteorites by scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy: Mundrabilla IAB ung. Meteorit. & Planet. Sci., 2023, 58, 1552–1562.

- Goryunov M.V., Felner I., Varga G., Dankházi Z., Chukin A.V., Naumov S.P., Leitus G., Muftakhetdinova R.F., Kuzmann E., Homonnay Z., Oshtrakh M.I. Magnetic features of some extraterrestrial Fe-Ni-Co alloys: study using magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Phys. B: Cond. Mat., 2025, 716, 417656.

- Oshtrakh M.I., Maksimova A.A., Goryunov M.V., Petrova E.V., Felner I., Chukin A.V., Grokhovsky V.I. Study of metallic Fe-Ni-Co alloy and stony part isolated from Seymchan meteorite using X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurement and Mössbauer spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct., 2018, 1174, 112–121.

- Oshtrakh M.I., Klencsár Z., Petrova E.V., Grokhovsky V.I., Chukin A.V., Shtoltz A.K., Maksimova A.A., Felner I., Kuzmann E., Homonnay Z., Semionkin V.A. Iron sulfide (troilite) inclusion extracted from Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite: composition, structure and magnetic properties. Mat. Chem. Phys., 2016, 174, 100–111.

- Gattacceca J., Rochette P., Lagroix F., Mathé P.-E., Zanda B. Low temperature magnetic transition of chromite in ordinary chondrites. Geophys. Res. Lett., 2011, 38, L10203.

- Kohout T., Haloda J., Halodová P., Meier M.M.M., Maden C., Busemann H., Laubenstein M., Caffee M.W., Welten K.C., Hopp J., Trieloff M., Mahajan R.R., Naik S., Trigo-Rodriguez J.M., Moyano-Cambero C.E., Oshtrakh M.I., Maksimova A.A., Chukin A.V., Semionkin V.A., Karabanalov M.S., Felner I., Petrova E.V., Brusnitsyna E.V., Grokhovsky V.I., Yakovlev G.A., Gritsevich M., Lyytinen E., Moilanen J., Kruglikov N.A., Ishchenko A.V. Annama H chondrite – mineralogy, physical properties, cosmic ray exposure, and parent body history. Meteorit. & Planet. Sci., 2017, 52, 1525–1541.

- Bandow S., Yamaguchi T., Iijima S. Magnetism of adsorbed oxygen on carbon nanohorns. Chem. Phys. Lett., 2005, 401, 380–384.

- Felner I. Peculiar magnetic features and superconductivity in sulfur doped amorphous carbon. Magnetochem., 2016, 2, 34.

- Felner I., Alenkina I.V., Vinogradov A.V., Oshtrakh M.I. Peculiar magnetic observations in pathological human liver. J. Mag. Mag. Mat., 2016, 399, 118–122.

- Maksimova A.A., Petrova E.V., Chukin A.V., Karabanalov M.S., Nogueira B.A., Fausto R., Yesiltas M., Felner I., Oshtrakh M.I. Characterization of Kemer L4 meteorite using Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A: Molec. and Biomolec. Spectroscopy, 2020, 242, 118723.

- Maksimova A.A., Oshtrakh M.I., Chukin A.V., Felner I., Yakovlev G.A., Semionkin V.A. Characterization of Northwest Africa 6286 and 7857 ordinary chondrites using X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A: Molec. and Biomolec. Spectroscopy, 2018, 192, 275–284.

- Gattacceca J., Suavet C., Rochette P., Weiss B.P., Winklhofer M., Uehara M., Friedrich J.M. Metal phases in ordinary chondrites: magnetic hysteresis properties and implications for thermal history. Meteorit. & Planet. Sci., 2014, 49, 652–676.

- Oshtrakh M.I., Larionov M.Yu., Grokhovsky V.I., Semionkin V.A. Study of rhabdite (iron nickel phosphide) microcrystals extracted from Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite by magnetization measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Mat. Chem. Phys., 2011, 130, 373–380.

- Oshtrakh M.I., Klencsár Z., Petrova E.V., Grokhovsky V.I., Chukin A.V., Shtoltz A.K., Maksimova A.A., Felner I., Kuzmann E., Homonnay Z., Semionkin V.A. Iron sulfide (troilite) inclusion extracted from Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite: composition, structure and magnetic properties. Mat. Chem. Phys., 2016, 174, 100–111.

- Kohout T, Kosterov A, Jackson M, Pesone,L.J, Kletetschka G, and Lehtinen, M Low-temperature magnetic properties of the Neuschwanstein EL6 meteorite, 2007, Earth and Planetary Science Lett.

- Bardos D.I. Mean magnetic moments in bcc Fe–Co alloys. J. Appl. Phys., 1969, 40, 1371–1372.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).