1. Introduction

Mine tailings are increasingly recognised as a potential source of mineral raw materials in response to growing metal demand and the need for sustainable resource management. Their characterisation and the recovery of valuable components have become an important part of contemporary resource and environmental policies [

1]. Mine tailings often contain significant amounts of metals that could not be recovered with the technologies available at the time of mining, were not economically viable, or were not analysed (or could not be analysed) at that time. In Serbia, tailings generated from polymetallic Pb–Zn mines are the second largest source of waste in the metal mining sector, due to an annual ore production of approximately 500 thousand tonnes [

2]. Despite their potential as secondary sources of metals, tailings from polymetallic deposits in Serbia have received limited scientific attention [

3,

4]. Until recently, only flotation tailings from the Grot mine had been subject to preliminary investigation [

5]. More recent studies have examined flotation tailings from the Rudnik mine, including mineralogical and environmental assessments [

6], and the flotation behaviour of minerals [

7,

8,

9].

The Rudnik mine, situated in central Serbia, is one of the most prominent and long-standing polymetallic mining sites. It hosts economically significant concentrations of Pb, Zn, Cu, and Ag and has been continuously exploited since 1953, with a total of over 14 million tonnes of ore extracted to date [

10]. The mine exploits a distal skarn deposit formed during Oligocene to Early Miocene magmatic-hydrothermal events, consistent with other deposits associated with volcano-intrusive complexes in the Balkan Peninsula [

11,

12,

13]. Sulfide ore is predominantly hosted within epidote-bearing skarn and occurs as massive bodies, stockwork veinlets, and disseminated mineralisation. The main sulfide minerals include sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite, with pyrrhotite, arsenopyrite, and pyrite as common gangue phases. Metal concentrations in ore vary considerably, ranging from 0.94 to 5.66 wt% Pb, 0.49 to 4.49 wt% Zn, 0.08 to 2.18 wt% Cu, and 50 to 297 µg/g Ag [

14].

Decades of mining and flotation processing of polymetallic ore have resulted in a tailings storage facility covering ~30 ha, with over 11 million tonnes (7 million m³) of material deposited to date (

Figure 1a, b). This flotation tailings, representing the residual fraction after beneficiation of PbS, ZnS, and CuFeS₂ concentrates, has evolved from initially supporting only Pb and Zn recovery to including Cu concentrates since 1988. Their mineralogical composition and heterogeneity position them simultaneously as a potential secondary resource and as a factor influencing long-term environmental impact. Consequently, the tailings storage facility represents both a challenge and an opportunity—requiring proper management to mitigate ecological risks while offering scope for revalorization through modern processing technologies. In this context, characterisation becomes essential for advancing sustainable resource management and circular economy strategies.

The present study provides the first comprehensive dataset on the mineralogical, geochemical, and magnetic susceptibility properties of flotation tailings samples from the Rudnik mine, thereby strengthening the knowledge base required for sustainable management and potential valorisation of tailings as secondary raw material sources in future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

Samples were obtained from three vertical trenches excavated within the tailings body, which occupies the bed of a former dry creek (

Figure 1a). In total, 16 samples (designated RW1–RW16) were collected (

Table 1). Trench T1 was sampled at 0.5 m intervals, whereas trenches T2 and T3 were sampled at 1 m intervals to evaluate vertical heterogeneity within the flotation tailings material. All samples were quartered: one quarter was stored in bags as a reference, while the opposite quarter was used for mineralogical analyses. The remaining two quarters from each trench were homogenised to produce composite samples that represent the vertical profiles. These composites were subsequently subdivided and prepared for further geochemical analyses and mass magnetic susceptibility measurements.

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction analyses were done on a "PHILIPS" X-ray diffractometer, model PW-1710, with a curved graphite monochromator and a scintillation counter. The intensities of diffracted CuKα X-rays (λ=1.54178Å) were measured at room temperature in intervals of 0.02o2θ and time of 1s in the range from 4 to 65o2θ. The X-ray tube was operated at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 30 mA, while the slits for directing the primary and diffracted beams were set to 1 mm and 0.1 mm, respectively.

2.3. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

Optical analyses were performed at the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Mining and Geology, using a Zeiss Axio Imager 2 reflected light microscope, and at the Institute for Technology of Nuclear and Other Mineral Raw Materials (ITNMS), using a Carl Zeiss-Jena JENAPOL-U polarising microscope for both reflected and transmitted light. Samples were subsequently examined with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-6610LV, JEOL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) operated at 20 kV. Mineral identification was supported by energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS, Xplore 30, Oxford Instruments, UK), with a detection limit of approximately 0.1 wt% based on internal standards. Backscattered electron (BSE) micrographs were used to evaluate mineral homogeneity and identify potential zoning features.

2.4. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

The chemical composition of the selected samples were performed using the SPECTRO Xepos C energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) spectrometer, with an air-cooled X-ray tube with a thick Pd/Co binary alloy anode operating at 50kV voltage and at tube power of 50W. The analyses were performed on fine-grained powder samples of 5g.

2.5. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra of the fine-grained powder materials were recorded using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two equipped with the Universal ATR accessory. The spectrum of each powder sample was recorded in the mid-infrared range 1600–400 cm−1 with 20 scans and a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES)

Selected trace elements (Cu, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Mn, Cr, Ba, As, Bi, and Ag) were analysed with a PERKIN-ELMER AVIO 200 ICP-OES. Plasma was generated by argon combustion in an oxygen stream, and a full-wavelength field detector simultaneously measured spectral ranges around the lines of interest. Sample digestion and preparation were carried out using an acid mixture (HNO₃:HCl = 3:1). The detection limit of the AVIO 200 ICP-OES is in the µg/L (ppb) range, typically 0.1–100 µg/L depending on the element. Standard reference material OREAS 135 was used for calibration and quality control (

https://www.oreas.com/crm/oreas-135/).

2.5. Laboratory Measurement of Magnetic Susceptibility (MS)

Magnetic susceptibility was measured at room temperature (~20 °C) under a low magnetic field of 400 A/m using an MFK-1A Kappabridge (AGICO Instruments, Brno, Czech Republic) with a sensitivity of 2 × 10⁻⁸ SI. Volume magnetic susceptibility was determined on dry samples of fixed volume (20 cm³). Sample mass was measured with a Radwag AS 220 R2 Plus analytical balance, accurate to four decimal places, to calculate mass magnetic susceptibility. Each sample was measured five times, and the mean value was used for further analysis. Before measurements, the magnetic susceptibility of the plastic bag and instrument holder was determined and used to correct the final values.

3. Results

3.1. Mineralogy

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of flotation tailings samples (RW1–RW16) reveals a consistent and complex mineral assemblage predominantly composed of silicate, carbonate, sulfate, and sulfide minerals (

Figure 2,

Table 2). Quartz and calcite are the most abundant phases across all samples. Sulfide minerals, including pyrite, sphalerite, chalcopyrite, galena, pyrrhotite, and arsenopyrite, accompany them. Accessory minerals such as chlorite, dolomite, and gypsum were also identified, while minor diffraction peaks suggest the presence of additional gangue minerals, including kaolinite or related clays, plagioclase, orthoclase, muscovite, anatase, and goethite.

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used for profiling the mine tailing samples components. The component identification based on characteristic band vibrations in the fingerprint region of 1600-400 cm

-1 is shown in

Figure 3. In the fingerprint region, the most intensive broad complex band in the 1100-950 cm

-1 range is assigned to the in-plane Si–O–Si stretching vibration in silicates. The bands at ca 1163, 1086 (shoulder), doublet 799 and 778, are assigned to stretching and banding vibrations in quartz. The strong and wide band at 1440-1420 cm

-1 is assigned to carbonates. Specifically, bands 876 and 712 cm

-1 are assigned to calcite. The intensities of quartz and carbonate bands suggest that those minerals are the most abundant, which is consistent with optical and XRD investigations. In addition, the bands belonging to feldspar and sulfates are also observed, the latter consistent with the gypsum identified by XRD.

3.1.3. Optical and Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

Optical and SEM-EDS analyses support the XRD results and provide additional insight into the textural and spatial relationships among the identified minerals (

Table 2). The tailings comprise a heterogeneous mixture of sulfides, native elements, and secondary oxidation products, embedded within a matrix dominated by silicates and carbonates (

Figure 4a). Most grains range in size from 200 to 400 µm. Sulfides and alteration products often appear as finer particles (<100 µm), whereas silicates and carbonates tend to form coarser grains (>500 µm).

Quartz is the most abundant, occurring as large, homogeneous, often euhedral grains that frequently exhibit well-developed intergrowths with sulfide minerals, particularly pyrite and sphalerite (

Figure 4a, b).

Calcite, epidote, garnet, and orthoclase are also common, most frequently occurring as dispersed grains of various sizes, and less commonly as intergrowths on sulfide grains (

Figure 4a, b). Ca-pyroxenes, diopside-hedenbergite, occur as subhedral to euhedral grains, though they are present only in minor quantities. Apatite and zircon appear as small, very rare, and dispersed grains.

Pyrite and arsenopyrite represent the most abundant sulfide minerals within the tailings, predominantly occurring as isolated grains and, to a lesser extent, as intergrowths with silicate phases (

Figure 4c). Pyrite grains display considerable size variability, often reaching coarse dimensions up to 400 µm. These grains are homogeneous, with rare inclusions of chalcopyrite and galena, which appear as droplet-shaped inclusions up to 40 µm in length. Partial to complete oxidation of pyrite is frequent, with hematite commonly present as a secondary alteration mineral (

Figure 4a, b). Arsenopyrite occurs as isolated, homogeneous, and unaltered grains of sizes comparable to pyrite (

Figure 4c).

Pyrrhotite is less abundant relative to pyrite and arsenopyrite and occurs intergrown with galena, sphalerite, and chalcopyrite (

Figure 4d). It occasionally contains flame- or vein-like pentlandite exsolutions less than 5 µm in length.

Among economically significant sulfides, sphalerite is the most prevalent. It occurs as individual grains that host chalcopyrite inclusions ranging from 10 to 40 µm and, less frequently, as simple intergrowths with other minerals, especially sulfides such as galena and chalcopyrite (

Figure 4e). Sphalerite grains range from below 50 µm to 500 µm in size.

Galena is commonly observed in complex intergrowths with sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and various silicate, oxide, and carbonate minerals, while isolated grains are subordinate. Its grain size ranges from 50 to 250 µm. Sometimes, galena is associated with native bismuth, native silver, and bismite (

Figure 4f, g). Secondary alteration along some grain boundaries is evidenced by the occurrence of cerussite (

Figure 4h).

Chalcopyrite forms fine impregnations within sphalerite or as small inclusions and simple intergrowths with Fe-sulfides (

Figure 4d, e). Grain sizes range from submicron to 100 µm. The chalcopyrite is rarely altered, although minor malachite coatings have been present on some grain surfaces.

3.1. Geochemistry

3.1.1. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES)

The most abundant oxide in all samples is SiO₂ (33.81–44.30 wt%;

Table 3), followed by Fe₂O₃ (19.02–28.74 wt%) and Al₂O₃ (7.69–10.57 wt%). Sulfur (S) contents vary widely (2.20–12.30 wt%). Among metals, Zn shows the greatest enrichment (0.21–0.79 wt%), followed by Pb (0.14–0.32 wt%) and Cu (0.05–0.17 wt%). Manganese (Mn) is present in moderate amounts (0.104–0.189 wt%), whereas Cr is consistently low (≤ 0.036 wt%). Arsenic (As) displays a broad range (0.012–0.732 wt%). Nickel (Ni) (0.011–0.023 wt%) and Co (0.003–0.007 wt%) contents remain consistently low. Bismuth (Bi) is present in trace yet potentially significant amounts (0.002–0.013 wt%), while Ag content is lower (6 to 19 µg/g).

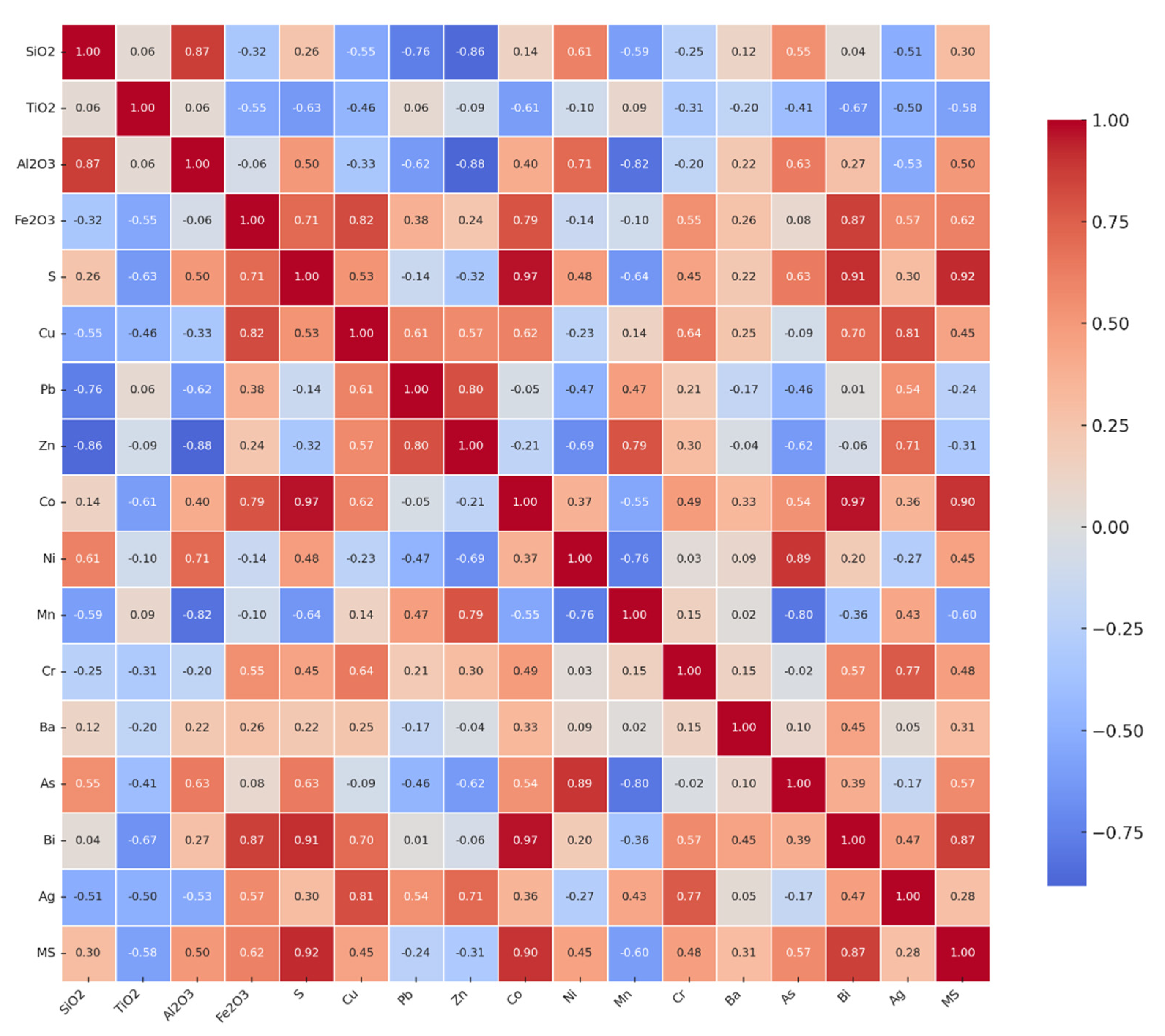

Pearson correlation analysis is performed to assess the relationships among oxides, elements, and magnetic susceptibility (MS) (

Figure 5).

Strong positive correlations (r ≥ 0.7) are between SiO2 and Al2O3 (r = 0.87). Al2O3 is also positively correlated with Ni (r = 0.71), while Fe2O3 shows strong positive correlations with Cu (r = 0.82), Bi (r = 0.87), and Co (r = 0.79). Sulfur (S) is strongly correlated with Co (r = 0.97) and Bi (r = 0.91), while with Cu and Ag (r = 0.81), as well as Zn and Mn (r = 0.79), also show strong positive correlations. Ni is strongly correlated with As (r = 0.89), and Bi with Co (r = 0.97). Ag is positively correlated with Cr (r = 0.77) and Zn (r = 0.71).

Moderate positive correlations (0.4 ≤ r < 0.7) are between SiO2 and Ni (r = 0.61) and As (r = 0.55), Al2O3 and S (r = 0.50) and As (r = 0.63), Fe2O3 and S (r = 0.71) and Cr (r = 0.55), S and Cu (r = 0.53) and Cr (r = 0.45), Cu and Pb (r = 0.61) and Co (r = 0.62), Ni and SiO2 (r = 0.61) and Al2O3 (r = 0.71), Co and Cr (r = 0.49), Cr and Cu (r = 0.64) and Fe2O3 (r = 0.55), Ag and Pb (r = 0.54) and Mn (r = 0.43).

Strong negative correlations (r ≤ -0.7) are between SiO2 and Zn (r = -0.86) and Pb (r = -0.76), Al2O3 and Zn (r = -0.88), Mn and Al2O3 (r = -0.82) and Ni (r = -0.76), and Zn and Ni (r = -0.69).

Moderate negative correlations (-0.7 < r ≤ -0.4) are between TiO2 and Fe2O3 (r = -0.55), S (r = -0.63), Co (r = -0.61), and Cu (r = -0.46), S and Mn (r = -0.64), Cu and Al2O3 (r = -0.33), as well as Ag and SiO2 (r = -0.51), TiO2 (r = -0.50), and Al2O3 (r = -0.530).

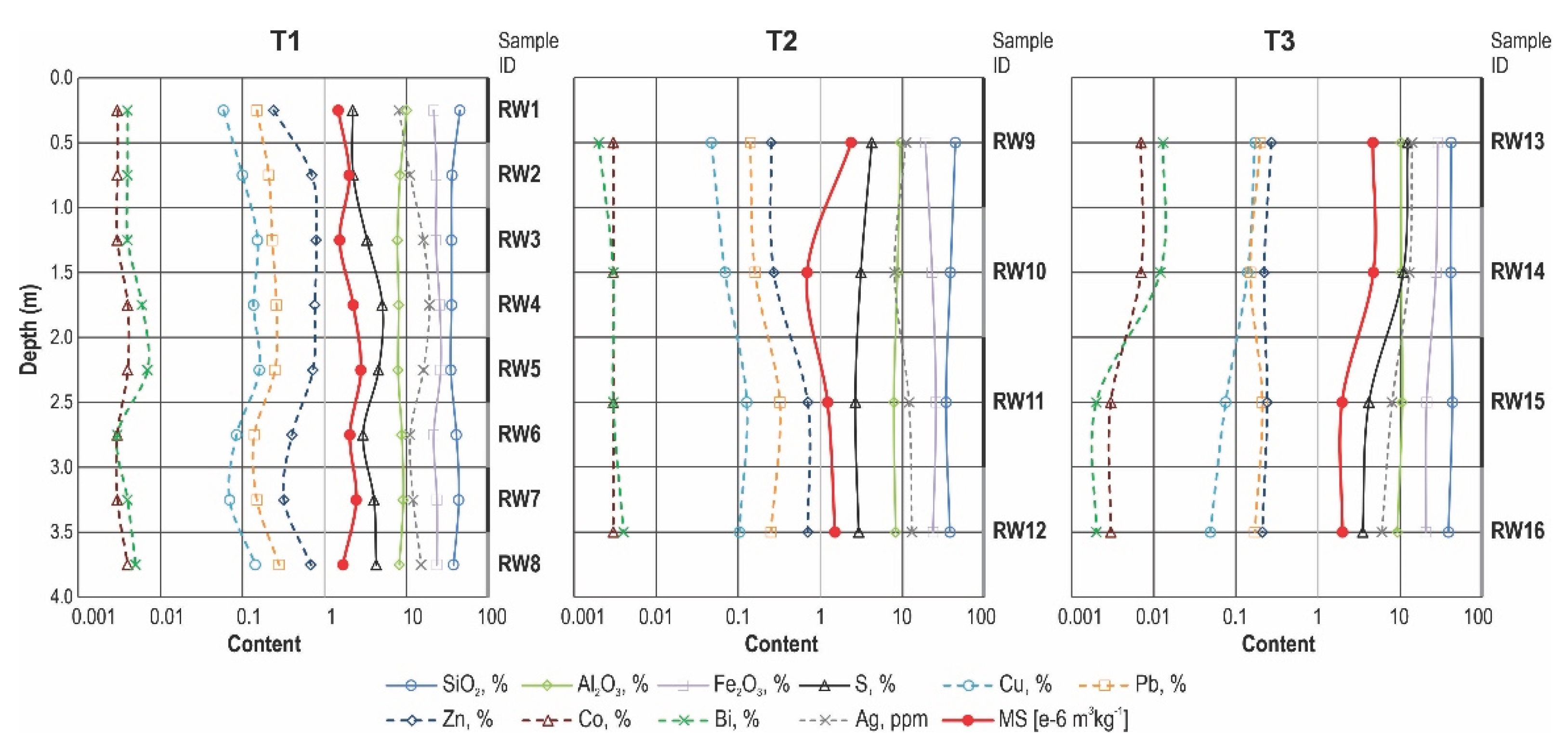

2.5. Magnetic Susceptibility

Mass magnetic susceptibility (MS) values of the flotation tailings samples exhibit considerable variability, ranging from 0.687 × 10⁻⁶ m³·kg⁻¹ to 4.724 × 10⁻⁶ m³·kg⁻¹, with an average value of 2.201 × 10⁻⁶ m³·kg⁻¹ (

Table 3). The highest values were recorded in samples RW13 and RW14, while the lowest were observed in RW10 and RW11. This variation reflects differences in the geochemical and mineralogical composition of the tailings, particularly the presence of iron-rich ferromagnetic minerals (

sensu lato) that demonstrate affinity toward specific metals (

Figure 5).

Strong positive correlations (r ≥ 0.7) with MS have S (r = 0.92), Co (r = 0.90), Bi (r = 0.87), and Ag (r = 0.87). Moderate positive correlations have Fe2O3 (r = 0.62), As (r = 0.57), Cr (r = 0.48), Al2O3 (r = 0.50), Cu (r = 0.45), and Ni (r = 0.45). Moderate negative correlations are observed for Mn (r = -0.60) and TiO2 (r = -0.58). Zn shows a weak negative correlation with MS (r = -0.31). Strong negative correlations (r ≤ -0.7) with MS are not observed.

4. Discussion

The polymetallic ore from the Rudnik mine is characterised by complex microtextural intergrowths of gangue and ore minerals, which can adversely influence ore processing efficiency [

17,

18]. In the flotation tailings, the dominant gangue minerals are quartz and calcite, accompanied by epidote, andradite, and diopside, reflecting the skarn-type mineralogy of the primary ore [

13,

19]. These gangue minerals are commonly intergrown with sulfides, forming fine-grained sulfide phases that are either embedded within or dispersed throughout a predominantly silicate–carbonate matrix. Among sulfides, pyrite, arsenopyrite, and pyrrhotite are dominant, followed by economically valuable sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite.

Post-depositional oxidative alteration is mostly pronounced near the surface, where atmospheric exposure promotes the oxidation of sulfides. Comparable alteration features are also observed at several depths within the tailings, mainly in material previously exposed at the surface and later buried by younger tailing material. Pyrite is particularly susceptible, frequently replaced by hematite along grain boundaries or via pseudomorphosis, illustrating natural weathering processes [

20]. Galena and chalcopyrite are likewise transformed, forming cerussite and malachite, respectively, whereas other sulfides remain relatively unaltered, resulting in heterogeneous oxidation patterns throughout the tailings. In comparison with nearby sites, oxidation in the Rudnik flotation tailings appears relatively limited [

21].

Geochemical data corroborates these mineralogical and petrographic observations. Elevated SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ contents confirm the prevalence of silicate and aluminosilicate gangue minerals, while increased Fe₂O₃ and S concentrations indicate a significant abundance of iron sulfides such as pyrite and pyrrhotite. Sulfur concentrations vary considerably (2.20–12.30 wt%), reflecting vertical heterogeneity in sulfide distribution (

Figure 6). Base metal contents—Zn (up to 0.79 wt%), Pb (up to 0.32 wt%), and Cu (up to 0.17 wt%)—provide further evidence of inefficiencies in historical ore processing. Although present in low concentrations, trace elements such as Ag and Bi may still hold economic significance for potential future recovery.

The sulfur content along the vertical profile of the T2 and T3 trenches indicates its decrease with depth, which further indicates the progressive decomposition of sulfide minerals with time (i.e. depth) and the migration of liberated sulfur in the form of sulfate via pore waters within the tailings body.

Correlation analysis provides additional insights into the geochemical controls of the tailings. The strong positive correlation between SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ (r = 0.87) is typical of aluminosilicate minerals (feldspars, clay minerals), which, together with quartz, dominate the gangue matrix. Conversely, significant positive correlations between Fe₂O₃ and Cu, Bi, Co, as well as between S and Co, Bi, highlight the controlling role of sulfide phases—chiefly pyrite, pyrrhotite, and arsenopyrite—in the geochemical behaviour of these elements [

22]. Correlations such as Cu–Ag, Zn–Mn, and Ni–As further reflect well-documented mineralogical linkages, including chalcopyrite with Ag, sphalerite with Mn, and arsenopyrite with Ni and As [

23,

24]. The exceptionally strong correlation between Bi and Co (r = 0.97) suggests a close association within Fe-sulfide phases, with possible implications for the recovery of critical metals [

25]. Negative correlations between SiO₂/Al₂O₃ and Zn/Pb highlight the contrast between the silicate–carbonate matrix, which is poor in metals, and the sulfide phases, which serve as the primary hosts of base metals. Similarly, negative associations between Mn and Al₂O₃/Ni indicate that manganese is linked to carbonate and oxide minerals, whereas Ni is predominantly controlled by the presence of sulfides.

Magnetic susceptibility (MS) data further reinforce these geochemical patterns. Strong positive correlations between MS and S, Co, Bi, and Ag demonstrate that sulfides and their alteration products (hematite, goethite) are the principal carriers of the magnetic signal [

26]. The highest MS values were measured in Fe-sulfide-rich samples (RW13, RW14), whereas samples dominated by the silicate–carbonate matrix yielded much lower values (

Figure 6). Negative correlations with Mn and TiO₂ suggest that oxide and carbonate phases reduce the overall magnetic response.

5. Conclusions

The flotation tailings of the Rudnik mine exhibit mineralogical and geochemical characteristics that reflect the complexity of the primary ore, the efficiency of mineral liberation and phase selectivity during flotation, as well as post-depositional alterations, including sulfide oxidation and secondary mineral formation. Key findings include:

Complex mineral associations and microtextural intergrowths of rock-forming minerals with sulfides hinder efficient flotation, resulting in fine-grained sulfides within the flotation tailings.

Flotation tailings are dominated by quartz and calcite, accompanied by epidote, andradite, and diopside. Economically valuable sulfides, including sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite, are mostly finer than 400 µm and occur as intergrowths or as free grains within the flotation tailings.

Post-depositional oxidation is moderately developed; pyrite is often replaced by hematite, galena by cerussite, and chalcopyrite by malachite, while other sulfides remain relatively unaltered.

High SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ confirm the dominance of silicate and aluminosilicate gangue, whereas elevated Fe₂O₃ and S reflect the presence of iron sulfides. Zn, Pb, and Cu concentrations are below 1%, while minor elements such as Ag and Bi, although present at low levels, may hold future economic potential.

Mass magnetic susceptibility supports the mineralogical observations: samples with higher Fe₂O₃ and S show elevated susceptibility, whereas samples with lower Fe₂O₃ exhibit reduced susceptibility, consistent with XRD and SEM-EDS analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., V.S., and D.Ž; methodology, N.N., J.S., V.C., J.M., and Lj.O.; validation, V.S., and D.Ž.; formal analysis, N.N., J.S., V.C., Lj.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., V.S.; writing—review and editing, V.C, D.Ž., N.N.; project administration, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, GRANT 7522 – REASONING and the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grant numbers: 451-03-136/2025-03/200126; 451-03-136/2025-03/200053; 451-03-136/2025-03/200023).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The permission to take samples and the determination of selected trace elements by the “Rudnik i flotacija Rudnik” Company is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Mining waste; European Commission — Environment. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/mining-waste_en#law (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024, 446 pp.

- Steiner, T.M.C.; Bertrandsson Erlandsson, V.; Šajn, R.; Melcher, F. Preliminary chemical and mineralogical characterization of tailings from base metal sulfide deposits in Serbia and North Macedonia. Geol. Croat. 2022, 75 (Special issue), 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajn, R.; Ristović, I.; Čeplak, B. Mining and metallurgical waste as potential secondary sources of metals—A case study for the West Balkan region. Minerals 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokić, B.V.; Jović, V.; Jovanović, M.; Ćirić, A.; Jovanović, D. Geochemical behaviour of some heavy metals of the Grot flotation tailing, Southeast Serbia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 66, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramović, F.; Cvetkov, V.; Ilić, A.; Životić, D. Korelacija magnetnog susceptibiliteta i sadržaja metala u flotacijskom jalovištu. XVIII Kongr. Geol. Srbije, Divčibare, 1–4 Jun 2022, pp. 23–24.

- Lazić, P.; Nikšić, Đ.; Miković, B.; Tomanec, R. Copper minerals flotation in flotation plant of the "Rudnik" mine. Podzemni Rad. 2019, (35), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, P.; Nikšić, D.; Tomanec, R.; Vučinić, D.; Cvetičanin, L. Chalcopyrite floatability in flotation plant of the Rudnik mine. J. Min. Sci. 2020, 56, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikšić, D.; Lazić, P.; Kostović, M. Flotability of chalcopyrite from the Rudnik deposit. J. Min. Sci. 2021, 57, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, R.; Umeljić, G. Metallogeny of the Rudnik Mountain, Position in Time and Space [Metalogenija planine Rudnik, pozicija u vremenu i prostoru]. Occas. Publ. Rudnik Flot., Belgrade, 2015; 224 pp.

- Cvetković, V.; Šarić, K.; Pécskay, Z.; Gerdes, A. The Rudnik Mts. volcano-intrusive complex (central Serbia): An example of how magmatism controls metallogeny. Geol. Croat. 2016, 69, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerler, J.; Von Quadt, A.; Burkhard, R.; Peytcheva, I.; Cvetković, V.; Baker, T. The Karavansalija mineralized center at the Rogozna Mountains in SW Serbia: Magma evolution and time relationship of intrusive events and skarn Au±Cu–Pb–Zn mineralization. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 798701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.; Bakker, R.J.; Cvetković, V.; Jelenković, R. Multiphase evolution of fluids in the Rudnik hydrothermal-skarn deposit (Serbia): New constraints from study of quartz-hosted fluid inclusions. Mineral. Petrol. 2024, 118, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, J.; Radosavljević-Mihajlović, A.; Radosavljević, S.; Vuković, N.; Pačevski, A. Mineralogy and genetic characteristics of the Rudnik Pb-Zn/Cu, Ag, Bi, W polymetallic deposit (Central Serbia)—New occurrence of Pb (Ag) Bi sulfosalts. Period. Mineral. 2016, 85, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Whitney, D.L.; Evans, B.W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerstenau, D.W.; Phatak, P.B.; Kapur, P.C.; Abouzeid, A.Z. Simulation of the grinding of coarse/fine (heterogeneous) systems in a ball mill. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 99, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L.; Mainza, A.N.; Becker, M.; Wiese, J.G. Using mineralogical and particle shape analysis to investigate enhanced mineral liberation through phase boundary fracture. Powder Technol. 2016, 301, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, J.N.; Radosavljević, S.A.; Tošović, R.D.; Pačevski, A.M.; Radosavljević-Mihajlović, A.S.; Kašić, V.D.; Vuković, N.S. A review of the Pb-Zn-Cu-Ag-Bi-W polymetallic ore from the Rudnik orefield, Central Serbia. Geol. An. Balk. Poluostrva 2018, 79, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Ballester, A.; Gonzalez, F.; Blázquez, M.L. Pyrite behaviour in a tailings pond. Hydrometallurgy 2005, 76, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravković, A.; Cvetković, V.; Pačevski, A.; Rosić, A.; Šarić, K.; Matović, V.; Erić, S. Products of oxidative dissolution on waste rock dumps at the Pb-Zn Rudnik mine in Serbia and their possible effects on the environment. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 181, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.J.; Corkhill, C.L. Mineralogy of sulfides. Elements 2017, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Ciobanu, C.L. Partitioning of trace elements in co-crystallized sphalerite–galena–chalcopyrite hydrothermal ores. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 77, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.L.; Cook, N.J.; Crowe, B.B.; Ciobanu, C.L. Trace elements in hydrothermal chalcopyrite. Mineral. Mag. 2018, 82, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godirilwe, L.L.; Gayratov, B.; Jeon, S.; Shibayama, A. Utilization of pyrite-rich tailings in sulfation roasting for efficient recovery of copper, nickel, and cobalt from smelter slag. [Journal Name], [Year], [Volume], [Pages].

- Dunlop, D.J.; Özdemir, Ö. Rock Magnetism: Fundamentals and Frontiers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).