1. Introduction

The exploitation of mineral resources plays a crucial role in stimulating economic growth and creating wealth. However, it is often associated with environmental impacts, leading to conflicts with other land uses. Mining is considered one of the most environmentally problematic activities within the primary sector, largely due to its contamination and habitat destruction legacy. When exposed to weathering processes, sulfide-rich mine waste generates acid mine drainage (AMD), a major source of environmental degradation. AMD is characterized by acidic effluents enriched in sulfate and metals that result from the oxidative dissolution of sulfide minerals in waste dumps (Chockalingam and Subramaniam, 2009; Valente et al., 2016). These contamination sources, both diffuse and point sources, release pollutants that are incorporated into various environmental reservoirs, such as aquatic systems, soils, and biological tissues, contributing to significant ecosystem degradation (Desenfant et al., 2004; Entwistle et al., 2019; Rezaie and Anderson, 2020). The impact is particularly severe in abandoned mines, where unmanaged wastes continue to cause environmental problems for decades or even centuries (Aska et al., 2024).

The Iberian Pyrite Belt (IPB), one of the largest metallogenic provinces in the world, is home to numerous abandoned mines that lack adequate protection measures for aquatic systems. Among these, the São Domingos mine, located in the Portuguese sector of the IPB, has been an important mining site since pre-Roman times. Mining activities continued until 1966, when operations were definitively closed (Álvarez-Valero et al., 2008). The São Domingos mine is characterized by the exploitation of massive sulfides in the Volcanic-Sedimentary Complex (VSC) (Matos and Martins, 2003). The mining legacy includes extensive waste dumps scattered over approximately 5.5 km along the São Domingos stream, which ultimately drains into the Chança reservoir. These waste dumps are the main source of contamination in the region’s water system, affecting both water quality and the storage capacity of reservoirs along the mining complex (Gomes et al., 2018).

Sediments from river systems affected by AMD are often enriched in magnetic phases and potentially toxic elements (PTEs). These elements can be incorporated into the crystalline structure of minerals or adsorbed onto particle surfaces (Kukier et al., 2003). Magnetic properties of sediments have been widely studied to understand various processes, including mineral-water interactions, pedogenesis, and the effects of climatic and environmental changes (Maher et al., 2003; Desenfant et al., 2004). Recent studies have highlighted the utility of rock magnetism in assessing environmental contamination and tracking pollution sources (e.g., Desenfant et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2018; Almeida et al., 2021). Also, magnetic properties have proven to be effective tools for investigating sediment dynamics in AMD-affected environments. Magnetic minerals such as magnetite, hematite, and goethite are commonly associated with AMD processes and can retain PTEs (Gomes et al., 2016; Sahoo et al., 2012). Thus, the study of magnetic properties can provide insights into contamination sources and the behavior of pollutants in sediments.

This study focuses on the São Domingos stream, a key pathway for AMD from the abandoned mine site to the surrounding environment. The primary objective is to investigate the sediments that contribute to the clogging of the mine water dams along the stream. A comprehensive analysis of magnetic, geochemical, and mineralogical properties was conducted by examining the sediments profiles from five clogged dams. Through this multidisciplinary approach, the study provides insights into the relationship between AMD processes, sediment dynamics, and PTE mobility in this historic mine of the IPB region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Work and Sample Preparation

The fieldwork involved drilling at five locations within mine dams constructed for water retention, which serve as key sites for sediment accumulation. Two locations (

Figure 1) were selected for detailed investigation due to their substantial sediment deposits and proximity to the mine waste dumps: S1 (0.9 m depth) and S4 (1.7 m depth).

Each core was divided into two sections—one preserved as a reference and the other designated for laboratory analysis. The cores were further segmented into 10 cm intervals, resulting in 10 subsamples for S1 and 18 subsamples for S4.

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction

After drying at 40 ºC, homogenization, and sieving to obtain the < 2 mm fraction, the samples were pulverized in an agate mortar. The mineralogical composition was obtained in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) Laboratory of Earth Sciences of the University of Minho. The XRD analyses were performed in powder samples, using Philips PW1710 equipment (APD - 3.6j version) with CuKα radiation, 40 kV voltage, and 20 mA. The equipment was operated with a step size of 0.02◦ 2-theta and a counting time of 1.25 s. The relative abundance of the mineral phases was estimated by measuring the intensity of diagnostic diffraction peaks as described in Brindley and Brown (1980).

2.3. Rock Magnetism

The magnetic properties of sediments were measured in the paleomagnetism laboratory of the Earth Sciences Department of the University of Coimbra. Magnetic susceptibility was measured with an MS2 meter (Bartington) and normalized by mass (χ em m3/kg). Magnetic susceptibility measures the ability of a material to be magnetized and includes contributions (in proportion to their abundance) from all diamagnetic (calcite), paramagnetic (clays), and ferromagnetic (magnetite) minerals present in the sediment.

Frequency-dependent magnetic susceptibility (Kfd in %) was calculated using the formula: Klf-Khf/Khf*100, where Klf and Khf are the magnetic susceptibility at low and high frequency respectively. Kfd (%) informs about the contribution of superparamagnetic particles. Isothermal remnant magnetization (IRM) curves were acquired using an impulse magnetizer (model IM-10-30). The IRM was measured with a Minispin magnetometer (Molspin). Samples were previously demagnetized using an alternating field (AF) of 100 mT. The IRM data were reported as mass-normalized (Am2/kg unit) with a constant volume of 10 cm3. The IRM curves were analyzed using a cumulative log-Gaussian (CLG) function (Kruiver et al., 2001) and a Skewed Generalized Gauss function (SGG) (Maxbauer et al., 2015) to discriminate magnetic phases by their respective coercivity spectra. The saturation of the isothermal remnant magnetization curves (SIRM) provide information regarding the concentration of the magnetic particles. The mean coercivity (B1/2), which corresponds to the value of the imparted field required to reach half of the saturation, provides information about the nature of the magnetic particles (ex. Magnetite, hematite, etc.). The dispersion parameter (DP) informs about the distribution of the coercivity spectra and informs about the nature and grain size distribution of the magnetic populations.

2.4. Chemical Analysis by ICP-MS

The pulverized samples of the < 2 mm fraction were subjected to extraction with Aqua Regia, which consists of an acid attack combining hydrochloric and nitric acid. Then, they were analyzed by mass spectrometry with plasma source induced (ICP-MS) in the Actlabs laboratory (Canada), including duplicate analysis, blanks, and certified standard materials for quality assurance and quality control (QC/QA) (reference materials from GXR series). Values for precision, as RSD%, were typically less than 15% for all elements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mineralogical Composition

The mineralogical composition is detailed in

Table 1, highlighting the minerals identified across the analyzed strata. Quartz emerges as the dominant mineral, consistent with the regional and local lithology described by Álvarez-Valero et al. (2008). Moreover, mineralization occurs in massive sulfide deposits associated with felsic volcanic rocks (Leistel et al., 1998), explaining the presence of plagioclase and micas. Also, the significant hydrothermal alteration of the host rocks of massive sulfide deposits (Sánchez-España et al., 2000) accounts for the prominent presence of clay minerals.

Jarosite (K₂Fe₆(OH)₁₂(SO₄)₄) was detected in nearly all samples. This hydroxysulfate is a typical secondary mineral in AMD environments, formed by the oxidative dissolution of sulfides (Bigham, 1994; Nordstrom and Alpers, 1999). In such a mineralized context, jarosite is expected to be a prevalent phase in mine waste deposits. Sulfide minerals were scarce, with pyrrhotite as the only sulfide identified. The scarcity of sulfides is attributed to the high redox potential of the environment, which promotes their instability and favors transformation into jarosite and/or goethite (Alpers et al., 1994; Valente and Leal Gomes, 2009).

Figure 2 illustrates a selection of phases based on their abundance and ubiquity (e.g., jarosite; pyrrhotite as a primary mineral and goethite as a secondary mineral formed by sulfide oxidation). Thus, the depth profiles globally reflect ore paragenesis, host rock mineralogy, and associated weathering products such as clay minerals.

Pyrrhotite is generally present at concentrations below 5%, while clay minerals and jarosite dominate, especially near the surface, consistent with more oxic conditions. In contrast, pyrrhotite is predominantly found between 20 and 60 cm depth. Notably, the highest concentration of siderite at 20 cm in S1 coincides with the absence of both jarosite and sulfide. This observation suggests that local equilibrium conditions favoring the presence of the carbonate inhibit the stability of sulfide and its weathering product.

3.2. Magnetic Properties

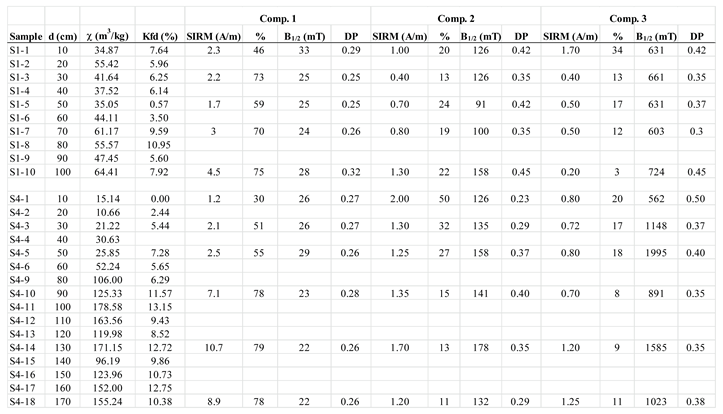

Low field mass-specific magnetic susceptibility (χ) varies from 34 × 10

-8 to 64 × 10

-8 m

3/kg in the S1 core, and from 10 × 10

-8 to 171 × 10

-8 m

3/kg in the S4 core (

Figure 3;

Table 2). In the S4 core, the lowest χ values are observed at the top of the core, while χ gradually increases to the highest values at the bottom of the core (

Figure 2). Kfd (%) varies from 3.5 to 10.9 % in the S1 core (except for sample S1-5 which has a Kfd of 0.6%), and from 0 to 13.2 % in the S4 core (

Figure 2). Kfd (%) between 2-10% indicates a mixture of grain sizes, with some superparamagnetic (SP) contribution. Kfd > 10% indicates a significant contribution of very fine-grained superparamagnetic particles, often associated with pedogenic particles (Dearing, 1999; Maher, 1988). In the S4 core, Kfd values gradually increase from the top to the bottom of the core, in correlation with χ, suggesting a gradual downward increase of SP particles.

Analysis of the IRM curves by a CLG and SGG functions indicates three main magnetic components in all samples. Fitting using the Kruiver et al. (2011) excel sheet or the MaxUnmix Software (Maxbauer et al., 2015) provided the same results.

Figure 4 represents the coercivity spectra obtained with the MAxUnmix software for two samples of each analyzed drills. Component 1 has a mean coercivity (B

1/2) of 22-33 mT and a dispersion parameter (SD) of 0.25-0.32, corresponding to the coercivity range of detrital and/or pedogenic magnetite (Egli, 2004). Component 1 contributes to 51-79 % of the total magnetization, except in the top of the core (Samples S1-1 and S4-1), where this contribution decreases up to 30 and 46 % (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4;

Table 2). Component 2 has B

1/2 values of 91 to 178 mT and DPof 0.23 to 0.45, corresponding either to hematite or fine-grained (high coercivity) magnetite. Component 2 contributes 11 % to 505 % of the total magnetization, with higher values observed at the top of the core. B

1/2 of component 3 varies from 600 to 1995 mT, with DP of 0.3-0.5, and corresponds to a high coercivity phase, probably goethite.

It is important to note that hematite and magnetite are not included among the phases listed in the mineralogical composition (

Table 1,

Figure 2). This highlights the complementary role of rock magnetism in overcoming the limitations of XRD analysis. The lower abundance of these oxides, compared to jarosite, precluded their detection by XRD. Nevertheless, their presence is clearly evidenced through these magnetic parameters.

3.3. Geochemical Relationships

Table 3 presents the chemical composition of samples regarding a set of representative elements. In general, the highest concentrations occur in S1. This high level of contamination in elements such as Pb and As can be mostly related to its location. This drill was obtained near the ore grinding and treatment plant (Achada do Gamo) of São Domingos mine, while S4 is located downstream. Therefore, these results may be a consequence of the leaching of these elements from the wastes accumulations to lower levels, in accordance with the runoff flow direction.

It is noteworthy that the highest concentrations of Pb (16700 and 12000 mg/kg) were detected in the samples with the highest amounts of jarosite (S1-1 and S1-10, respectively). The same for Cu and As. Thus, as extensively documented in literature, the ability of jarosite for adsorbing toxic elements (references) should be responsible for its retention, justifying the observed concentrations.

Table 4 shows the correlation between Fe, Pb, As, Cu the MS and SIRM in the studied drills. These elements were selected for representing the ore paragenesis, high concentrations in the sediment and environmental threat (Gomes et al., 2016). The results reveal that MS and SIRM have high correlations for both drills, with 0.97 and 1.00, respectively. According to Cunha et al. (2019), these results are indicative that MS is mainly controlled by the concentration of ferromagnetic iron.

Comparing the magnetite and hematite SIRM values in the studied sediments, with literature values of alluvial plain sediments of quaternary terraces (Cunha et al., 2019) (

Table 5), it is realized that the São Domingos materials are more magnetic.

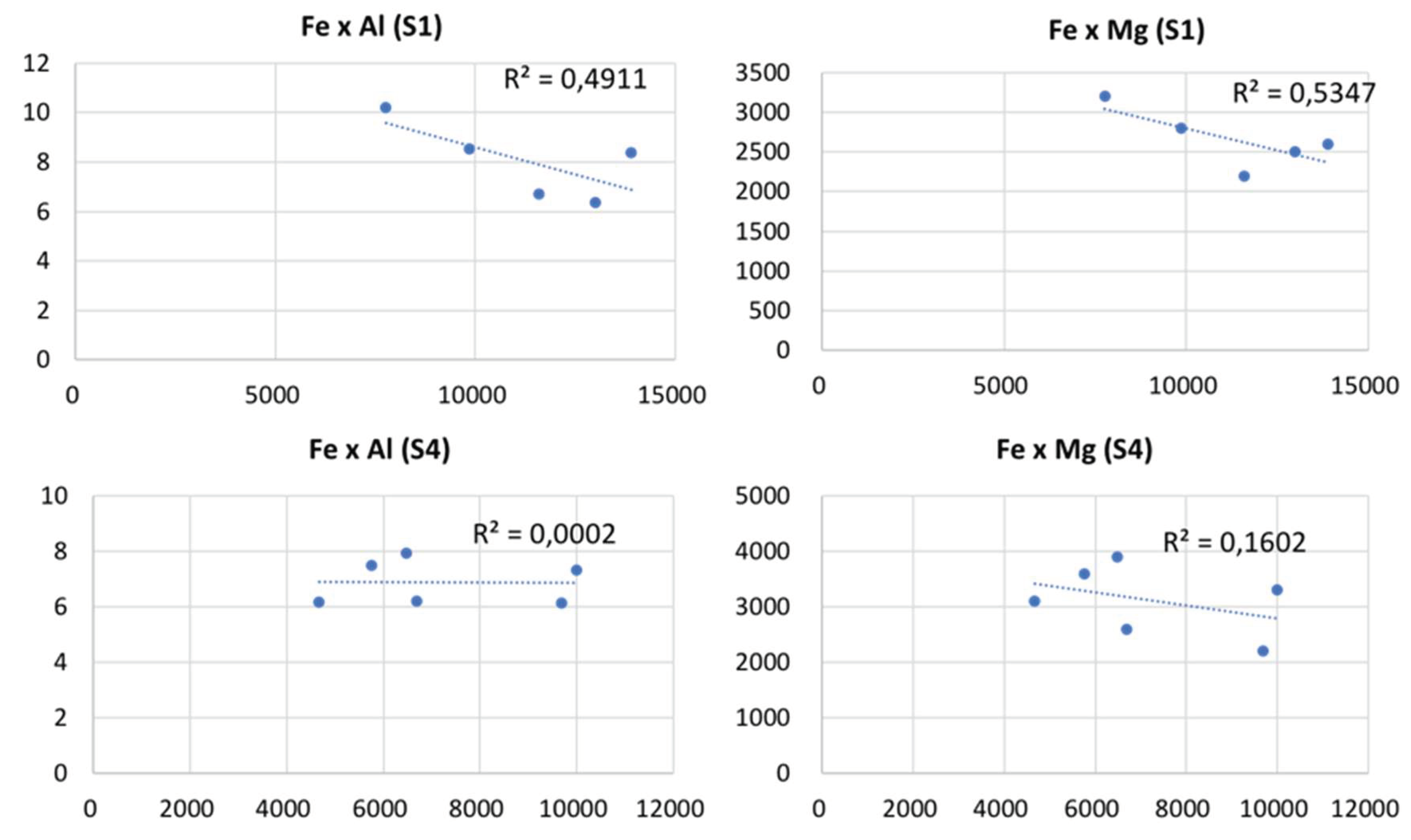

Nevertheless, when performing the study of chemical elements relationships (

Table 4), the results reveal low correlation coefficients. With regard to Fe, for example, it is also possible to observe a low correlation between MS and IRM. The correlations are between 0.3 and 0.4 in S1, and negative when analyzed for S4. These results suggest that Fe is not associated with magnetic particles identified with MS and IRM curves, because there is no notable correlation between these parameters.

Some correlation can be observed between toxic elements, particularly As and Pb (0.83 in S4) and As and Cu (0.7 in S1). Other correlations, such as among Fe, As and Cu, are also relevant, although less expressive (between 0.5 and 0.6). As mentioned above, these PTE constitute an integral part of primary paragenesis, having therefore a common origin expressed in this correlation. According to Gomes et al. (2016) and Valente et al. (2012), Fe may be associated with clay particles and/or iron oxyhydroxides (goethite) and hydroxysulfates (jarosite). Nonetheless, the correlation among Fe, Mg, and Al (

Figure 5) is practically absent in S4, suggesting that Fe is not associated with clays either. Thus, it can be deduced that jarosite should be the main Fe reservoir, as it is a very abundant mineral in the whole environment, especially in this drill -

Figure 1).

4. Conclusion

The mineralogical, geochemical, and magnetic analyses of sediments from the São Domingos mine reveal complex interactions between primary mining-associated minerals and secondary weathering products in an AMD environment. Jarosite, the predominant non-magnetic mineral, plays a crucial role in retaining PTEs such as lead, arsenic, and copper, especially near mining waste deposits.

Despite the high iron concentration in the sediments, no significant correlation was found between iron and magnetic minerals (magnetite, hematite, and goethite), indicating that iron is primarily hosted in jarosite. The low pH (<3) and high redox potential favor its stability, while the scarcity of sulfide minerals suggests their transformation into secondary phases like jarosite and goethite.

Magnetic phases play a limited role in PTE transport, being mainly controlled by magnetite, with minor contributions from hematite and goethite. Geochemical correlations indicate that PTEs are more strongly associated with jarosite than with magnetic minerals, reinforcing that their mobility is primarily influenced by non-magnetic iron-rich phases.

This study highlights the importance of a multi-parameter approach to understanding pollutant behavior in AMD environments. It also emphasizes the need for further research on the long-term stability and mobility of PTEs, as well as the potential for using magnetic methods as complementary tools for environmental monitoring and remediation in AMD-affected areas.

References

- Alpers, C.N., Blowes, D.W., Nordstrom, D.K., & Jambor, J. L. (1994) Secondary minerals and acid mine-water chemistry. In J. L. Jambor & D. W. Blowes (Eds.), Environmental Geochemistry of Sulfide Mine-Wastes. Mineralogical Association of Canada Short Course Handbook, 22, 247-270.

- Álvarez-Valero, A.M., Pérez-López, R., Matos, J.X., Capitán, M.A., Nieto, J.M., Saez, R., Delgado, J., Caraballo, M. (2008) Potential environmental impact at São Domingos mining district (Iberian Pyrite Belt, SW Iberian Peninsula): evidence from a chemical and mineralogical characterization. Environ Geololgy. 55, 1797–1809. [CrossRef]

- Aska, B., Franks, D.M., Stringer, M.; Sonter, L. (2024) Biodiversity conservation threatened by global mining wastes. Nature Sustainability 7, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Bigham, J.M. (1994) Mineralogy of ochre deposits formed by sulfide oxidation. In: Jambor, J.L., Blowes, D.W. (Eds.), Environmental Geochemistry of Sulfide Mine-Wastes. Mineralogical Association of Canada,103–132.

- Brindley, G.W. (1980) Order-disorder in clay mineral structures. In G. W. Brindley e G. Brown, Eds., Crystal Structures of Clay Minerals and their X-ray Identification, 125-195 p. Mineralogical Society, London.

- Chockalingam, E., Subramaniam, S. (2009) Utility of Eucalyptus tereticornis (Smith) bark and Desulfotomaculum nigrificans for the remediation of acid mine drainage. Bioresource Technology 100, 615-621. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P., Gouveia, M., Ferreira, C., Martins, A., Buylaert, J., Murray, A., Font, E., Pereira, T., Figueiredo, S., Bridgland, D., Yang, P., Stevaux, J, Mota, R. (2019) The Lowermost Tejo River Terrace at Foz do Enxarrique, Portugal: A Palaeoenvironmental Archive from c. 60–35 ka and Its Implications for the Last Neanderthals in Westernmost Iberia. Quaternary. [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J. (1999) Environmental Magnetic Susceptibility. Using the Bartington MS2 System, second edition. Chi Publishing, England, 54.

- Desenfant, F., Petrovsky, E., Rochette, P. (2004) Magnetic signature of industrial pollution of stream sediments and correlation with heavy metals: Case study from South France. Water Air Soil Pollut. 152, 297–312. [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, J.A., Hursthouse, A.S., Marinho Reis, P.A., Stewart, A.G. (2019) Metalliferous Mine Dust: Human Health Impacts and the Potential Determinants of Disease in Mining Communities. Curr Pollution Rep, 5, 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Gomes P.; Valente T.; Sequeira Braga M.A.; Grande J.A.; de la Torre M.L. (2016) - Enrichment of trace elements in the clay size fraction of mining soils. Environ Sci Pollut R. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.; Valente T.; Pereira P. (2018) Addressing quality and usability of surface water bodies in a Mediterranean semi-arid region. Environ. Process. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-España, J., Velasco, F., Yusta, I. (2000) Hydrothermal alteration of felsic volcanic rocks associated with massive sulphide deposition in the northern Iberian Pyrite Belt (SW Spain), Applied Geochemistry, 15-9, 1265-1290. [CrossRef]

- Leistel, J.M., Marcoux, E., Thiéblemont, D., Quesada, C., Sánchez, A., Almodóvar, G.R., Pascual, E., Sáez, R. (1998) The volcanic-hosted massive sulphide deposits of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. Review and preface to the Thematic issue. Miner. Deposita, 33, 2-30. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Roberts, A. P., Larrasoaña, J. C., Banerjee, S. K., Guyodo, Y., Tauxe, L., & Oldfield, F. (2012) Environmental magnetism: Principles and applications. Reviews of Geophysics, 50(4). [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, D. K., & Alpers, C. N. (1999) Geochemistry of acid mine waters. Reviews in Economic Geology, 6A, 133-160. [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.X., Martins,L. (2003) Geological-geotechnical characterization of the S. Domingos mine open pit, Iberian Pyrite Belt. Actas IV Cong. Int. Património Geol Miner, 539-557.

- Maher, B.A., Alekseev, A., Alekseeva, T. (2003) Magnetic mineralogy of soils across the Russian Steppe: Climatic dependence of pedogenic magnetite formation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. [CrossRef]

- Maxbauer, D. P., Feinberg, J. M. & Fox, D. L. MAX UnMix: A web application for unmixing magnetic coercivity distributions. Comput. Geosci. 95, 140–145 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Pan, H., Lu, X., Lei, K., Shi, D., Ren, C., Yang, L., Wang, L. (2018). Using magnetic susceptibility to evaluate pollution status of the sediment for a typical reservoir in northwestern China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25(15), 14606-14617. [CrossRef]

- Pesic, B., Oliver, D.J., Wichlacz, P. (1989) An electrochemical method of measuring the oxidation rate of ferrous to ferric iron with oxygen in the presence of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biotechnol Bioeng, 33(4): 428-439. [CrossRef]

- Kruiver, P.P., Dekkers, M.J., and Heslop, D. (2001) Quantification of magnetic coercivity components by the analysis of acquisition curves of isothermal remanent magnetisation: Earth Planet Sc Lett, 189, 269–276. [CrossRef]

- Kukier, U., Fauziah, C., Summer, M.E., Miller, W.P. (2003) Composition and element solubility of magnetic and non- magnetic fly ash fractions. Environ Pollut 123:255–266. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K., Tripathy, S., Panigrahi, M.K., Equeenuddin, Sk. Md. (2012) Mineralogy of Fe-Precipitates and Their Role in Metal Retention from an Acid Mine Drainage Site in India. Mine Water Environ 31, 344–352. [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, B., Anderson, A. (2020) Sustainable resolutions for environmental threat of the acid mine drainage. Science of the Total Environment, 717. [CrossRef]

- Valente, T., Gomes, P., Pamplona, J., de la Torre, M.L. (2012) Natural stabilization of mine waste-dumps - Evolution of the vegetation cover in distinctive geochemical and mineralogical environments. J. Geochemical Explor. 123, 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Valente, T., Rivera, M.J., Almeida, S.F.P., Delgado, C., Gomes, P., Grande, A., de la Torre, M.L., Santisteban, M. (2016) Characterization of water reservoirs affected by acid mine drainage: geochemical, mineralogical, and biological (diatoms) properties of the water. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:6002–6011. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).