Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The white-rot fungus Coriolopsis trogii MUT3379 produces laccase Lac3379-1 in high yields due to the previous implementation of a robust fermentation process. Throughout the extended use of this strain, we observed the occurrence of substrate-specific and transient alternative guaiacol and ABTS (2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)) oxidizing enzymes. Since we could not produce these enzymes in significant amounts using conventional strain selection and fermentation tools, we developed an approach based on protoplast preparation and regeneration to isolate stable producers of these alternative oxidative enzymes from the complex multinucleate mycelium of C. trogii MUT3379. A cost-effective and efficient protocol for protoplast preparation was developed using the enzymatic cocktail VinoTaste Pro by Novozymes. A total of 100 protoplast-derived clones were selected and screened to produce laccases and/or other oxidative enzymes. A variable spectrum of oxidative activity levels, including both high and low producers, was revealed. Notably, a subset of clones exhibited different guaiacol/ABTS positive enzymatic patterns. These findings suggest that it is possible to separate different lineages from the mycelium of C. trogii MUT337 producing a different pattern of oxidative enzymes, unravelling the potential of fungal division of labour to discover novel metabolic traits that otherwise remain cryptic. These data hold outstanding significance for accessing and producing novel oxidative enzymes from native fungal populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Cultivation of C. trogii MUT3379 and Production of Oxidative Enzymes

Protoplast Preparation and Manipulation

Enzyme Assays

NATIVE-PAGE Electrophoresis and Zymograms

Tandem Mass Spectrometry

3. Results

Production of Laccases and Other Oxidative Enzymes in C. trogii MUT3379

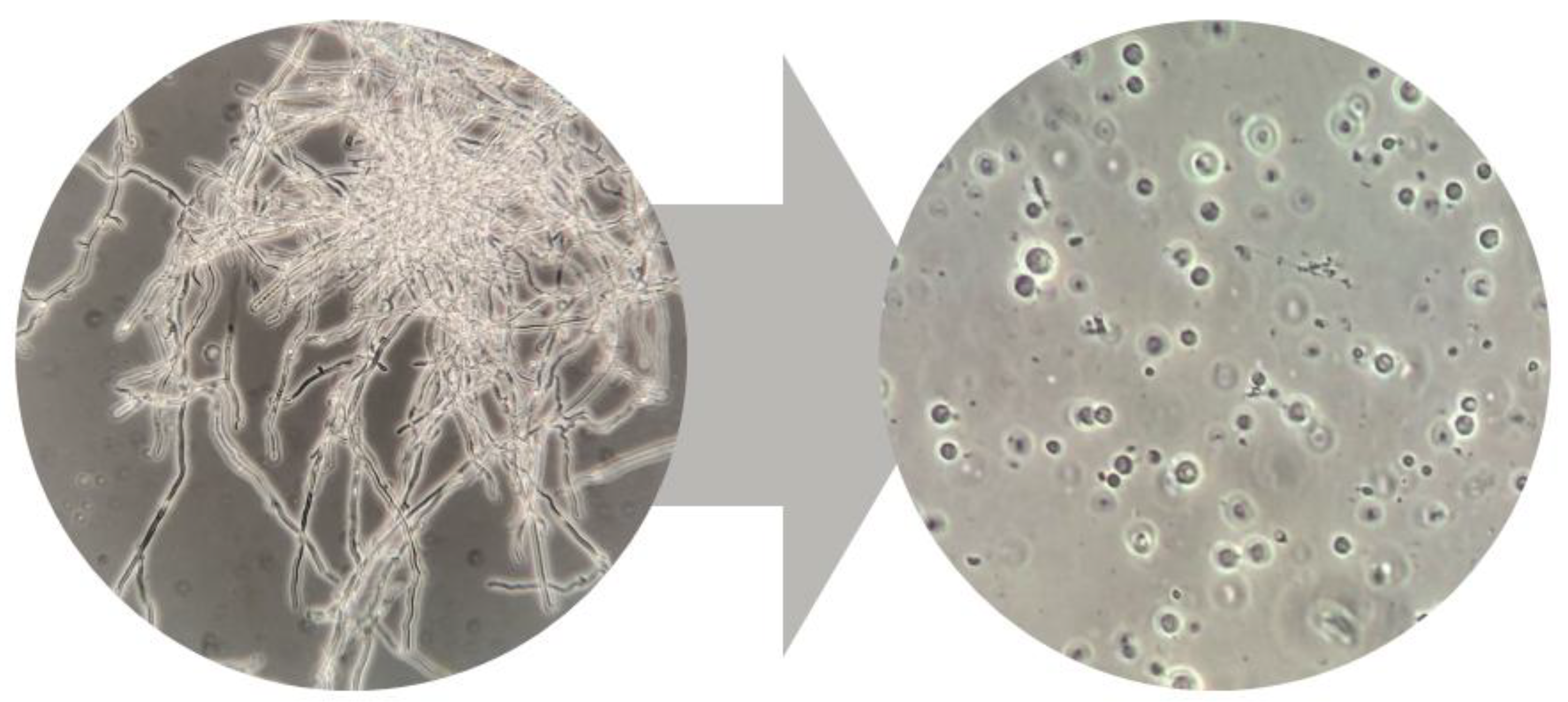

Protoplast-Derived Clone Isolation

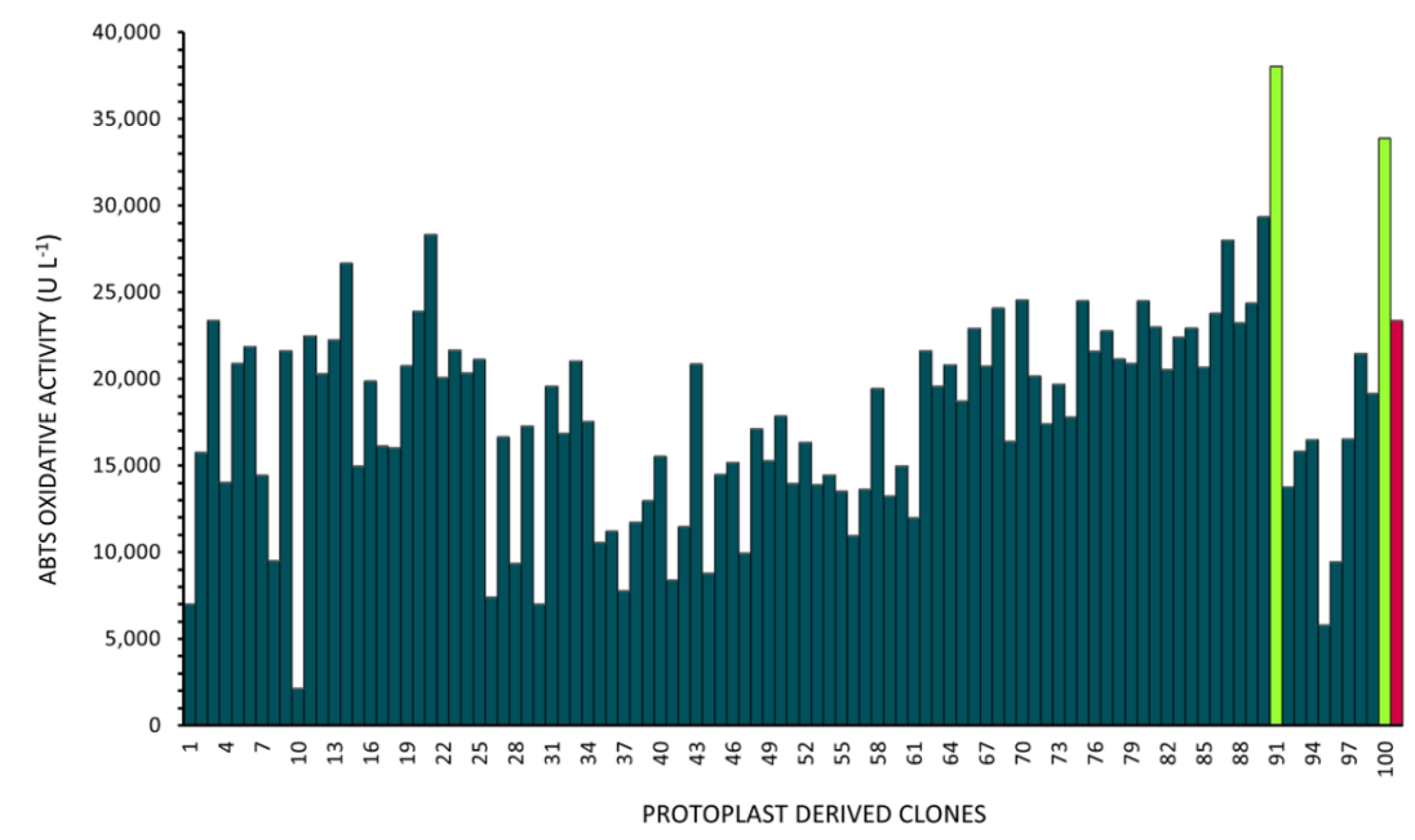

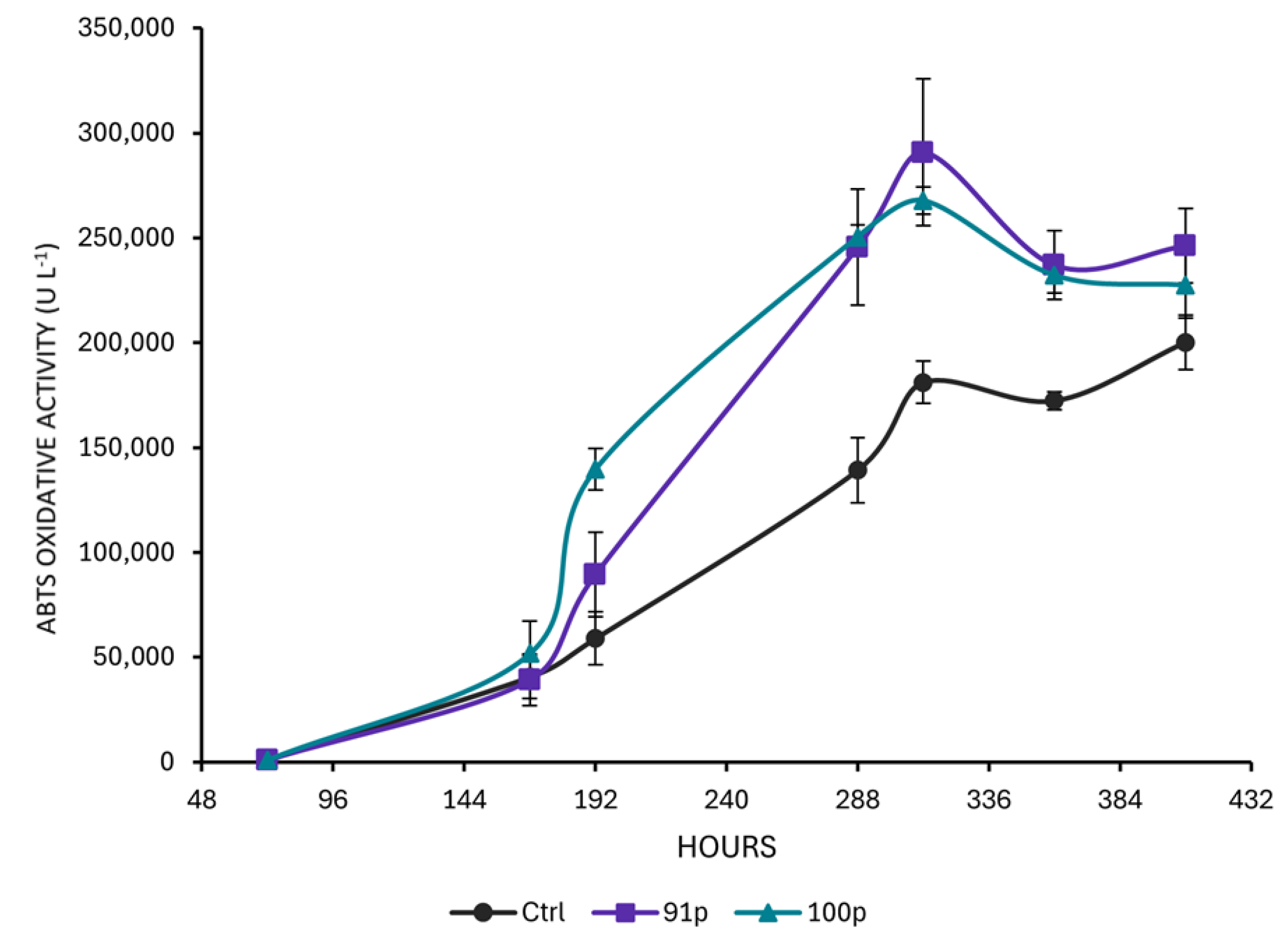

Quantification of the Oxidative Activity in the Protoplast-Derived Clones

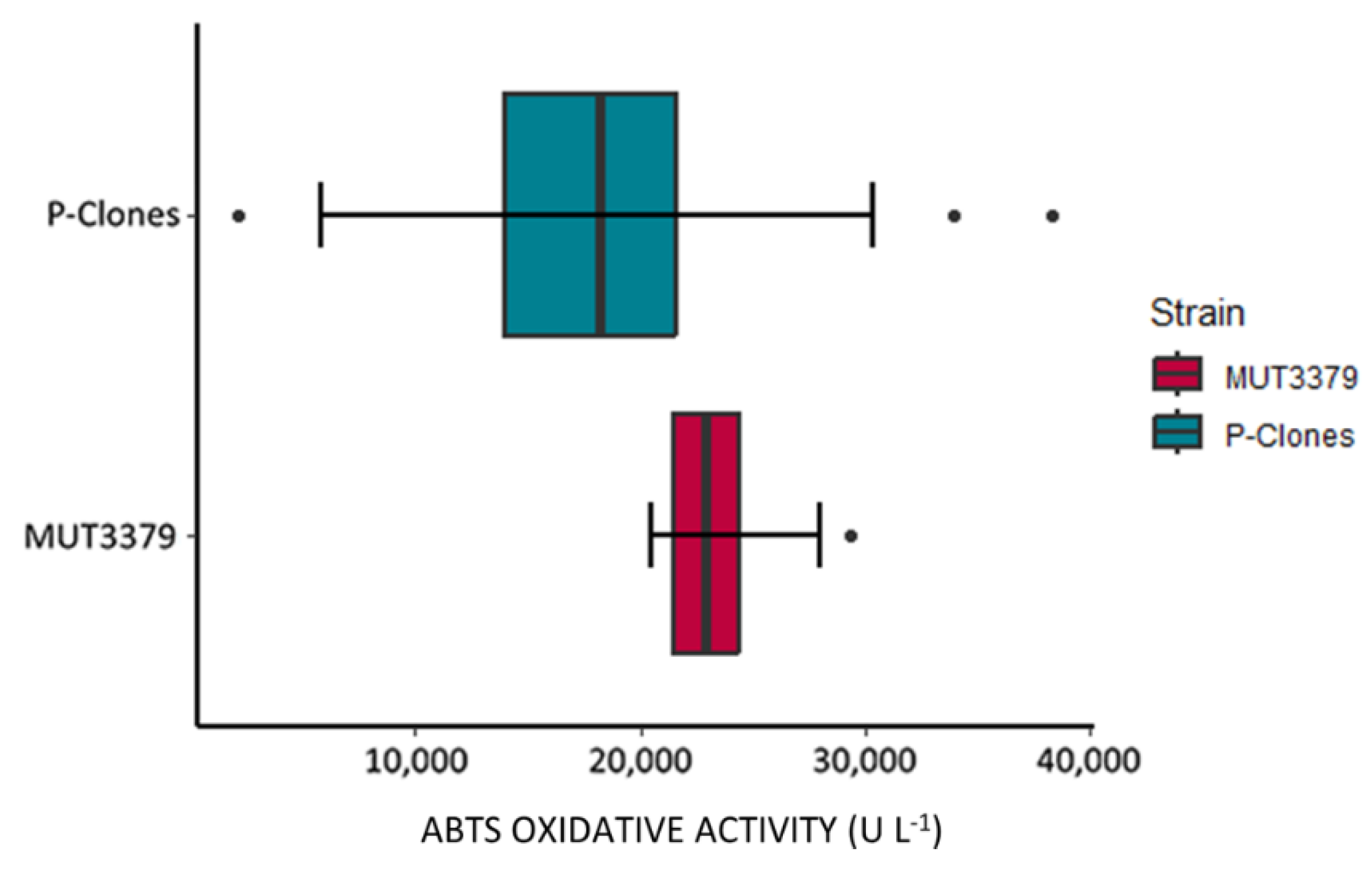

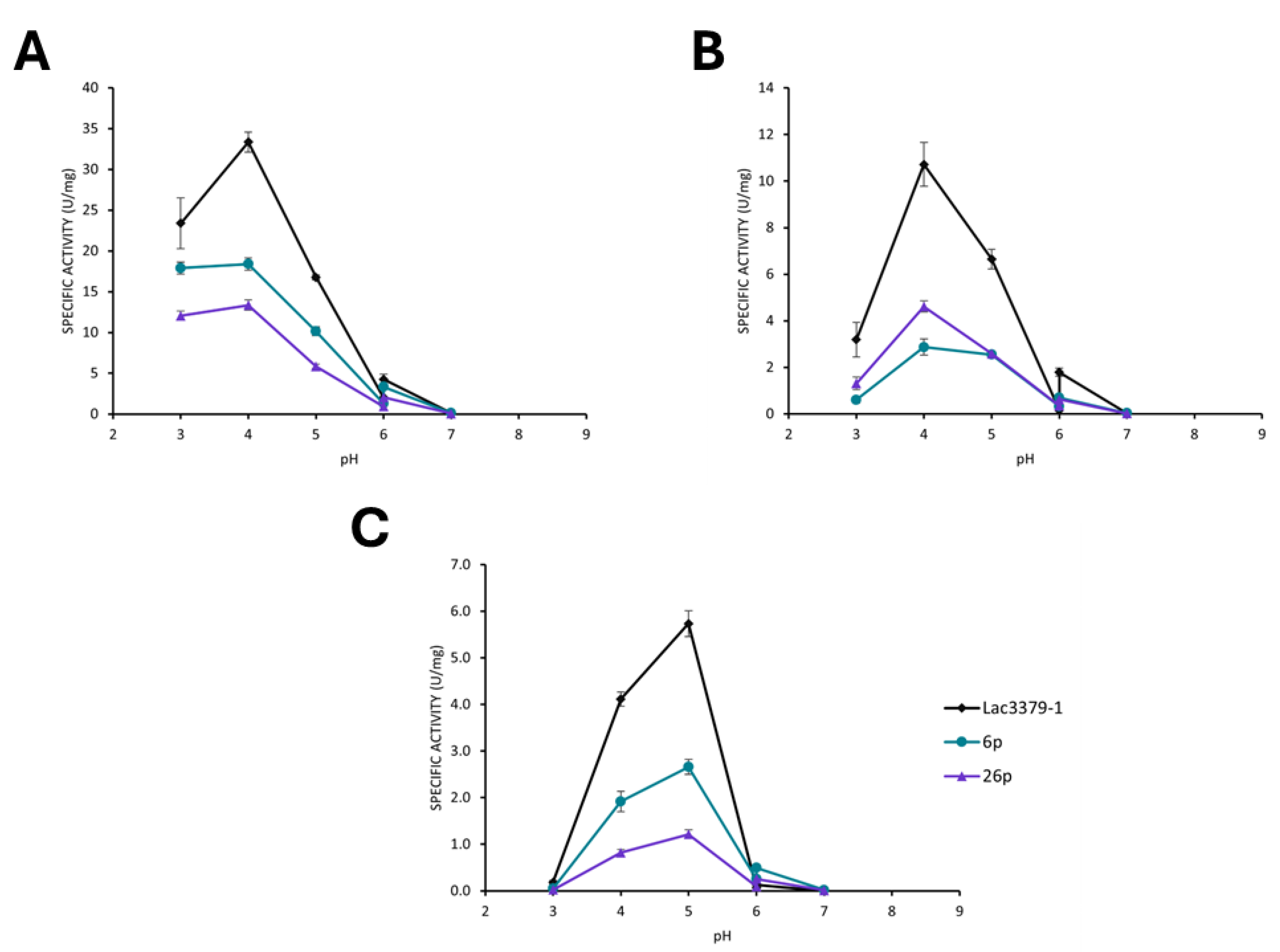

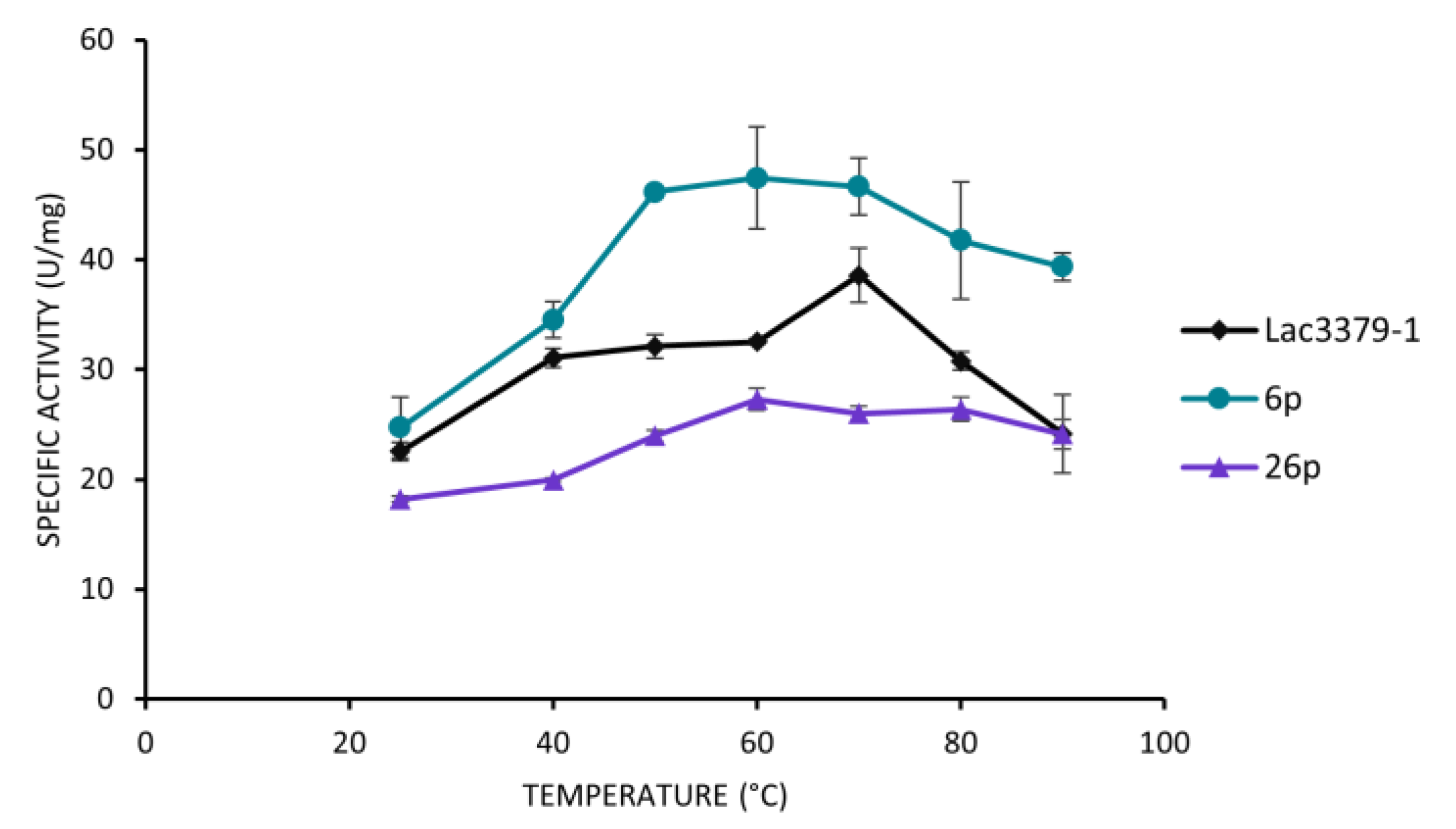

Comparison of the Oxidative Potential of the Protoplast-Derived Clones

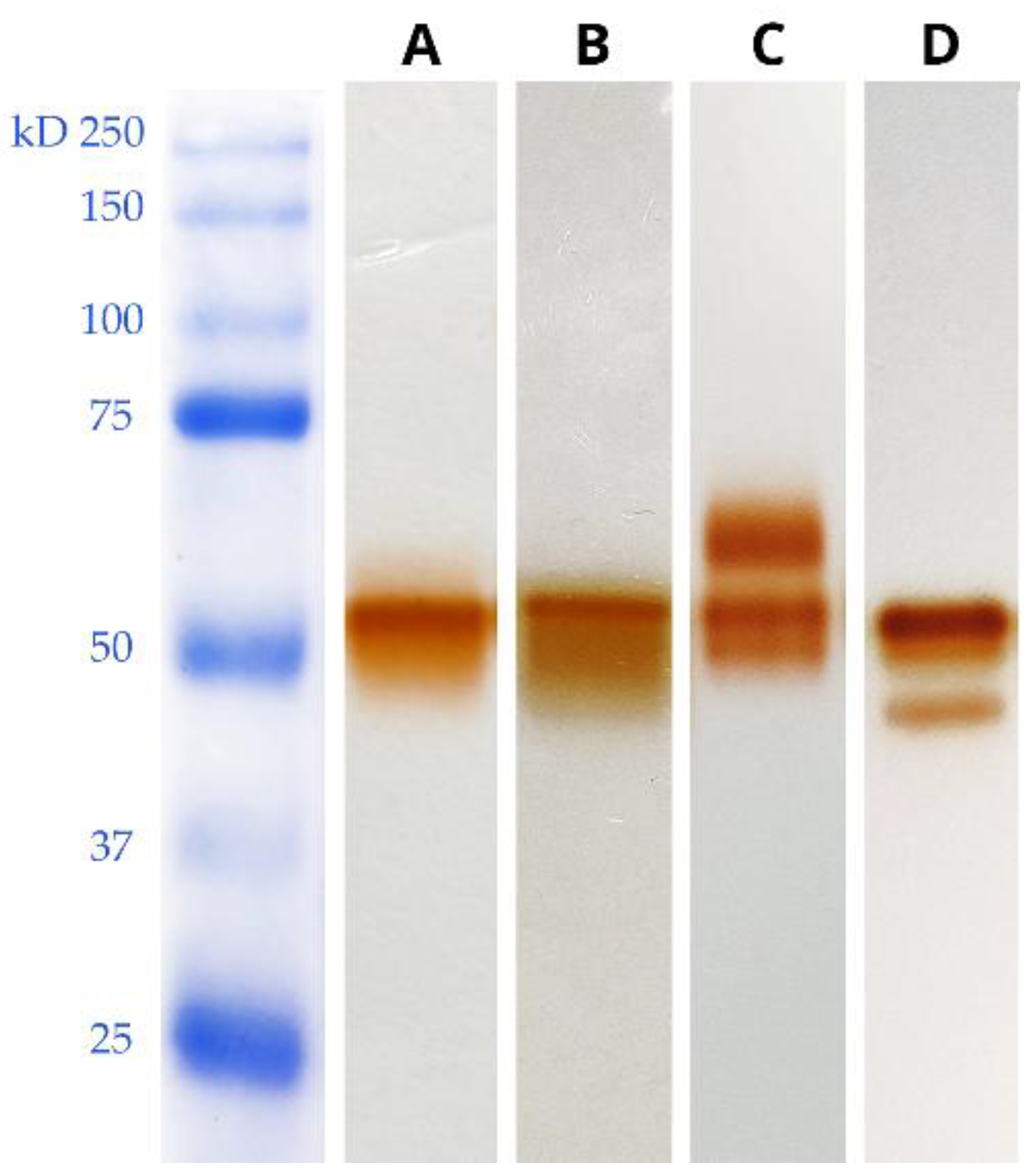

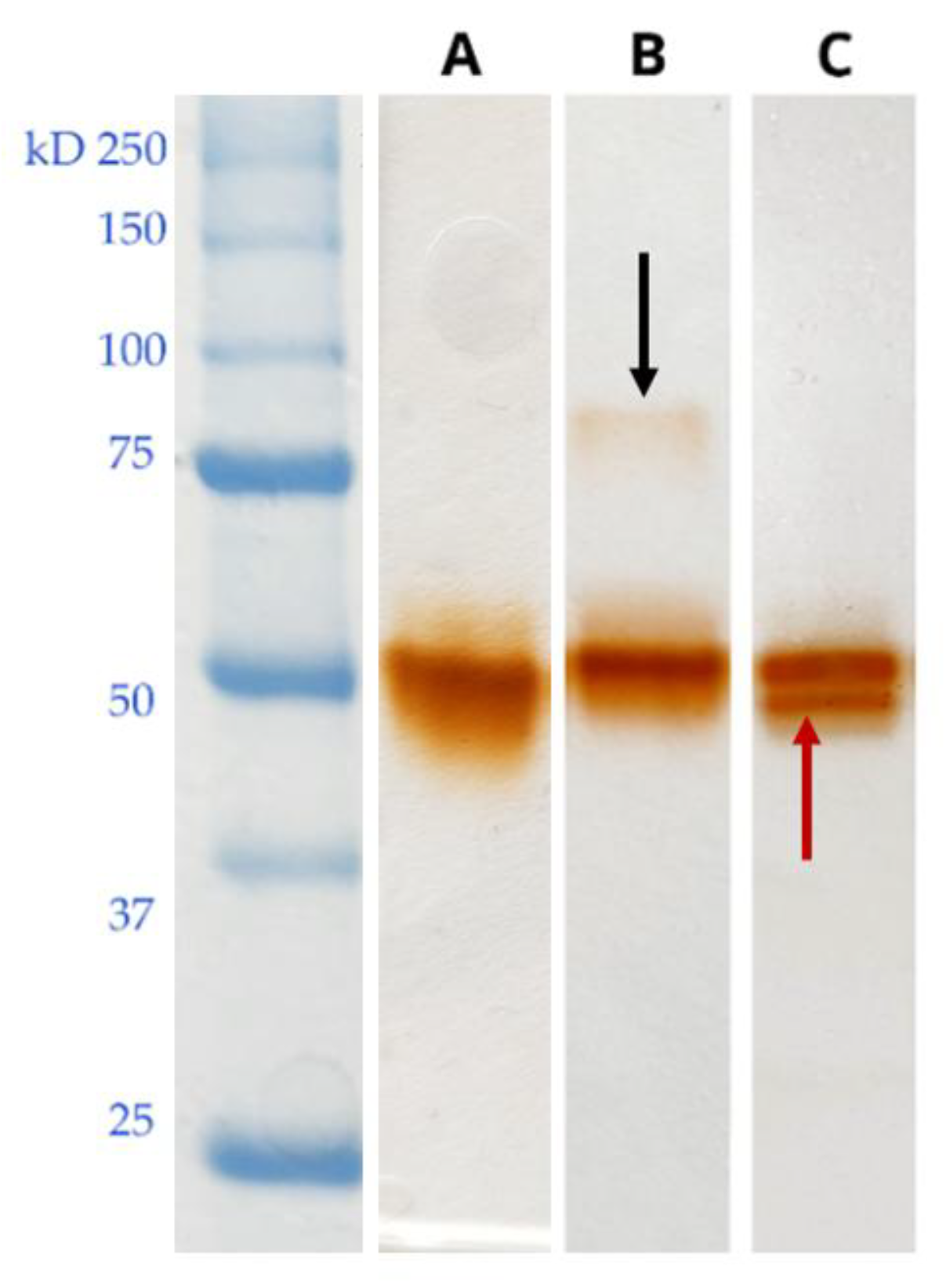

Identification of the Proteins Mapping in the Ox-L and Ox-H Bands

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bentil, J.A. Biocatalytic Potential of Basidiomycetes: Relevance, Challenges and Research Interventions in Industrial Processes. Sci Afr 2021, 11, e00717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Forest Microbiome: Diversity, Complexity and Dynamics. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, N. The Mycota. A Comprehensive Treatise on Fungi as Experimental Systems for Basic and Applied Research; 2002; Vol. 77; ISBN 9783540706151.

- Zhang, Z.; Claessen, D.; Rozen, D.E. Understanding Microbial Divisions of Labor. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traxler, M.F.; Rozen, D.E. Ecological Drivers of Division of Labour in Streptomyces. Curr Opin Microbiol 2022, 67, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, C.; de Barsy, F.; Liem, M.; Liakopoulos, A.; van Wezel, G.P.; Choi, Y.H.; Claessen, D.; Rozen, D.E. Antibiotic Production in Streptomyces Is Organized by a Division of Labor through Terminal Genomic Differentiation. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellere, L.; Bava, A.; Capozzoli, C.; Branduardi, P.; Berini, F.; Beltrametti, F. Strain Improvement and Strain Maintenance Revisited. The Use of Actinoplanes Teichomyceticus Atcc 31121 Protoplasts in the Identification of Candidates for Enhanced Teicoplanin Production. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchetti, B.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Claessen, D. Multiscale Heterogeneity in Filamentous Microbes. Biotechnol Adv 2018, 36, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, A.; Palma-Guerrero, J.; Fricker, M.; Louise Glass, N. Physiological Significance of Network Organization in Fungi. Eukaryot Cell 2012, 11, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijgsheld, P.; Nitsche, B.M.; Post, H.; Levin, A.M.; Müller, W.H.; Heck, A.J.R.; Ram, A.F.J.; Altelaar, A.F.M.; Wösten, H.A.B. Deletion of FlbA Results in Increased Secretome Complexity and Reduced Secretion Heterogeneity in Colonies of Aspergillus Niger. J Proteome Res 2013, 12, 1808–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moukha, S.M.; Wosten, H.A.B.; Asther, M.; Wessels, J.G.H. In Situ Localization of the Secretion of Lignin Peroxidases in Colonies of Phanerochaete Chrysosporium Using a Sandwiched Mode of Culture. J Gen Microbiol 1993, 139, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Tobon, G.; Kurzatkowski, W.; Rozbicka, B.; Solecka, J.; Pocsi, I.; Penninckx, M.J. In Situ Localization of Manganese Peroxidase Production in Mycelial Pallets of Phanerochaete Chrysosporium. Microbiology (N Y) 2003, 149, 3121–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, N.B.; Bushley, K.E. Two Genomes Are Better than One: History, Genetics, and Biotechnological Applications of Fungal Heterokaryons. Fungal Biol Biotechnol 2016, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalov, A.; Heller, J.; Herzog, S.; Fleißner, A.; Glass, N.L. Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Cell Fusion and Heterokaryon Formation in Filamentous Fungi. The Fungal Kingdom 2017, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.P. The Mycota XIII: Fungal Genomics; 2006; ISBN 9783540793069.

- Vande Zande, P.; Zhou, X.; Selmecki, A. The Dynamic Fungal Genome: Polyploidy, Aneuploidy and Copy Number Variation in Response to Stress. Annu Rev Microbiol 2023, 77, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martzy, R.; Mello-de-Sousa, T.M.; Mach, R.L.; Yaver, D.; Mach-Aigner, A.R. The Phenomenon of Degeneration of Industrial Trichoderma Reesei Strains. Biotechnol Biofuels 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hong, S.; Tang, G.; Wang, C. Accumulation of the Spontaneous and Random Mutations Is Causative of Fungal Culture Degeneration. Fundamental Research 2024, 0–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellere, L.; Bellasio, M.; Berini, F.; Marinelli, F.; Armengaud, J.; Beltrametti, F. Coriolopsis Trogii MUT3379 : A Novel Cell Factory for High-Yield Laccase Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinova, O.S.; Moiseenko, K. V.; Vavilova, E.A.; Chulkin, A.M.; Fedorova, T. V.; Tyazhelova, T. V.; Vasina, D. V. Evolutionary Relationships between the Laccase Genes of Polyporales: Orthology-Based Classification of Laccase Isozymes and Functional Insight from Trametes Hirsuta. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahama, T.; Furumai, T.; Okanishi, M. A Modified Regeneration Method for Streptomycete Protoplasts. Agric Biol Chem 1981, 45, 1271–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pible, O.; Allain, F.; Jouffret, V.; Culotta, K.; Miotello, G.; Armengaud, J. Estimating Relative Biomasses of Organisms in Microbiota Using “Phylopeptidomics”. Microbiome 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A.; Dulermo, R.; Ortet, P.; Blanchard, L.; Guérin, P.; Fernandez, B.; Vacherie, B.; Dossat, C.; Jolivet, E.; Siguier, P.; et al. Alliance of Proteomics and Genomics to Unravel the Specificities of Sahara Bacterium Deinococcus Deserti. PLoS Genet 2009, 5, e1000434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.G.M.; Tychanowicz, G.K.; De Souza, D.F.; Peralta, R.M. Production of Laccase Isoforms by Pleurotus Pulmonarius in Response to Presence of Phenolic and Aromatic Compounds. J Basic Microbiol 2004, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, G.; Ng, T.B.; Lin, J.; Ye, X. Laccase Production and Differential Transcription of Laccase Genes in Cerrena Sp. in Response to Metal Ions, Aromatic Compounds, and Nutrients. Front Microbiol 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.A.; Cooper, G.A. Division of Labour in Microorganisms: An Evolutionary Perspective. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016, 14, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, A.D.M.; Ramsdale, M.; Watkins, Z.R. Origins and Significance of Genetic and Epigenetic Instability in Mycelial Systems. Canadian Journal of Botany 1995, 73, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, V.M.; Ra, Y.; Sue, C.; Alcala, E.; Reaso, J.N.; Ruzin, S.E.; Traxler, M.F. Genetic Network Architecture and Environmental Cues Drive Spatial Organization of Phenotypic Division of Labor in Streptomyces Coelicolor. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, M.; Ellison, C.; Taylor, J.W.; Glass, N.L. Nuclear and Genome Dynamics in Multinucleate Ascomycete Fungi. Current Biology 2011, 21, R786–R793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Enshasy, H.A. Fungal Morphology: A Challenge in Bioprocess Engineering Industries for Product Development. Curr Opin Chem Eng 2022, 35, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiter, L.; Rajamanickam, V.; Herwig, C. The Filamentous Fungal Pellet—Relationship between Morphology and Productivity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Z. Morphological Regulation of Aspergillus Niger to Improve Citric Acid Production by ChsC Gene Silencing. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2018, 41, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, K.; Yoshimi, A.; Yoshimi, A.; Abe, K.; Abe, K.; Abe, K. The Mechanisms of Hyphal Pellet Formation Mediated by Polysaccharides, α-1,3-Glucan and Galactosaminogalactan, in Aspergillus Species. Fungal Biol Biotechnol 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pombeiro-Sponchiado, S.R.; Sousa, G.S.; Andrade, J.C.R.; Lisboa, H.F.; Gonçalves, R.C.R. Production of Melanin Pigment by Fungi and Its Biotechnological Applications. Melanin 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullah, S.; Hazarika, D.J.; Goswami, G.; Borgohain, T.; Ghosh, A.; Barooah, M.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Boro, R.C. Melanin Production and Laccase Mediated Oxidative Stress Alleviation during Fungal-Fungal Interaction among Basidiomycete Fungi. IMA Fungus 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, M.; Dufossé, L.; Singh, S.K. The Enigmatic World of Fungal Melanin: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlquist, M.; Fernandes, R.L.; Helmark, S.; Heins, A.L.; Lundin, L.; Sørensen, S.J.; Gernaey, K. V.; Lantz, A.E. Physiological Heterogeneities in Microbial Populations and Implications for Physical Stress Tolerance. Microb Cell Fact 2012, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herpoël, I.; Moukha, S.; Lesage-Meessen, L.; Sigoillot, J.C.; Asther, M. Selection of Pycnoporus Cinnabarinus Strains for Laccase Production. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2000, 183, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Andrew Alspaugh, J.; Liu, H.; Harris, S. Fungal Morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, N.; Harris, S.D.; Everhart, S.E. Evolutionary Significance of Fungal Hypermutators: Lessons Learned from Clinical Strains and Implications for Fungal Plant Pathogens. mSphere 2022, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, A.M.; De Vries, R.P.; Conesa, A.; De Bekker, C.; Talon, M.; Menke, H.H.; Van Peij, N.N.M.E.; Wösten, H.A.B. Spatial Differentiation in the Vegetative Mycelium of Aspergillus Niger. Eukaryot Cell 2007, 6, 2311–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Juan, J.; Kuai, B.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H. Transcriptome and Differentially Expressed Gene Profiles in Mycelium, Primordium and Fruiting Body Development in Stropharia Rugosoannulata. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehinger, M.O.; Croll, D.; Koch, A.M.; Sanders, I.R. Significant Genetic and Phenotypic Changes Arising from Clonal Growth of a Single Spore of an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus over Multiple Generations. New Phytologist 2012, 196, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, T.; Masclaux, F.G.; Rosikiewicz, P.; Pagni, M.; Sanders, I.R. Population Genomics Reveals That Within-Fungus Polymorphism Is Common and Maintained in Populations of the Mycorrhizal Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis. ISME Journal 2016, 10, 2514–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübeck, M.; Lübeck, P.S. Fungal Cell Factories for Efficient and Sustainable Production of Proteins and Peptides. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peberdy, J.F. Protein Secretion in Filamentous Fungi - Trying to Understand a Highly Productive Black Box. Trends Biotechnol 1994, 12, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.V.S.; Phale, P.S.; Durani, S.; Wangikar, P.P. Combined Sequence and Structure Analysis of the Fungal Laccase Family. Biotechnol Bioeng 2003, 83, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, G.; Giardina, P.; Bianco, C.; Fontanella, B.; Sannia, G. Copper Induction of Laccase Isoenzymes in the Ligninolytic Fungus Pleurotus Ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000, 66, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.V.S.; Phale, P.S.; Durani, S.; Wangikar, P.P. Combined Sequence and Structure Analysis of the Fungal Laccase Family. Biotechnol Bioeng 2003, 83, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, C.; Pan, J.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Pleurotus Eryngii Laccase Gene (PeLac) Family and Functional Identification of PeLac5. AMB Express 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Ng, T.B.; Lin, J.; Ye, X. Laccase Gene Family in Cerrena Sp. HYB07: Sequences, Heterologous Expression and Transcriptional Analysis. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasina, D. V.; Moiseenko, K. V.; Fedorova, T. V.; Tyazhelova, T. V. Lignin-Degrading Peroxidases in White-Rot Fungus Trametes Hirsuta 072. Absolute Expression Quantification of Full Multigene Family. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0173813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).