Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

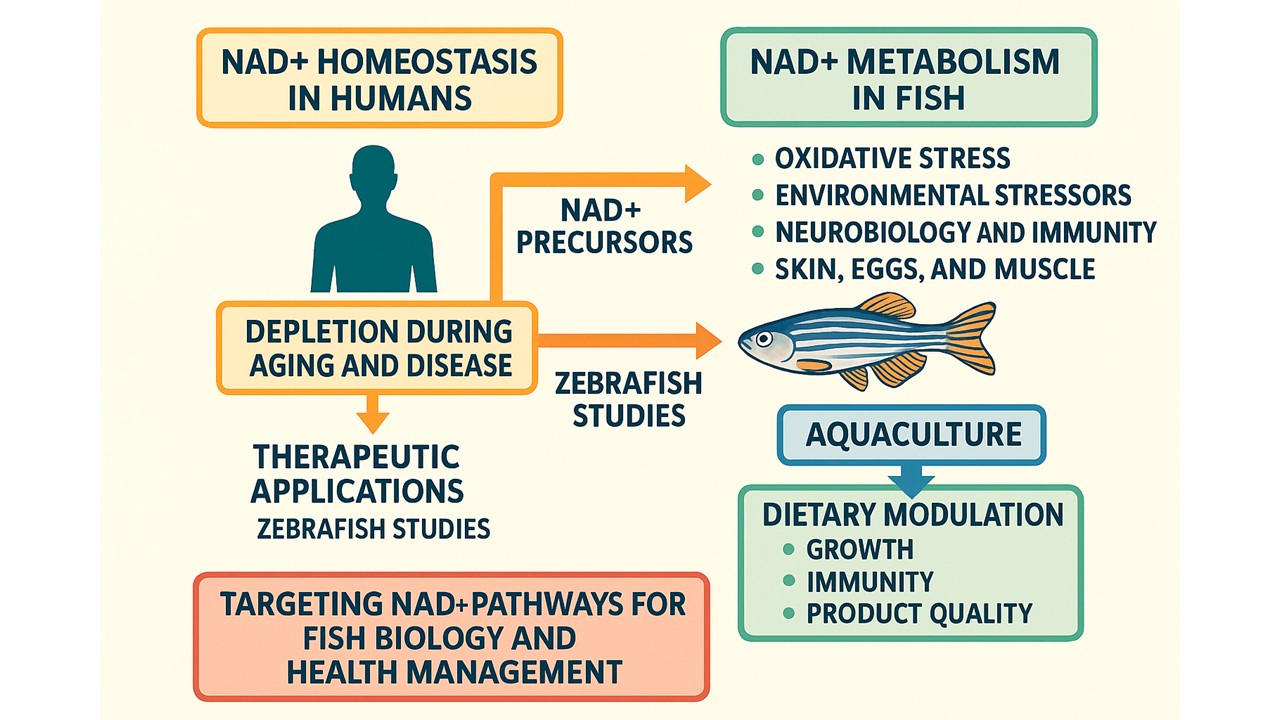

1. Introduction

2. Overview of NAD+ Biology And Its Balance in Human Health and Disease

2.1. Reduction in NAD+ Levels Is Associated with Aging and Numerous Age-Related Diseases.

2.2. Potential Therapeutic Value of NAD+ Precursors

3. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Models for Exploring NAD+-Related Pathways in Humans

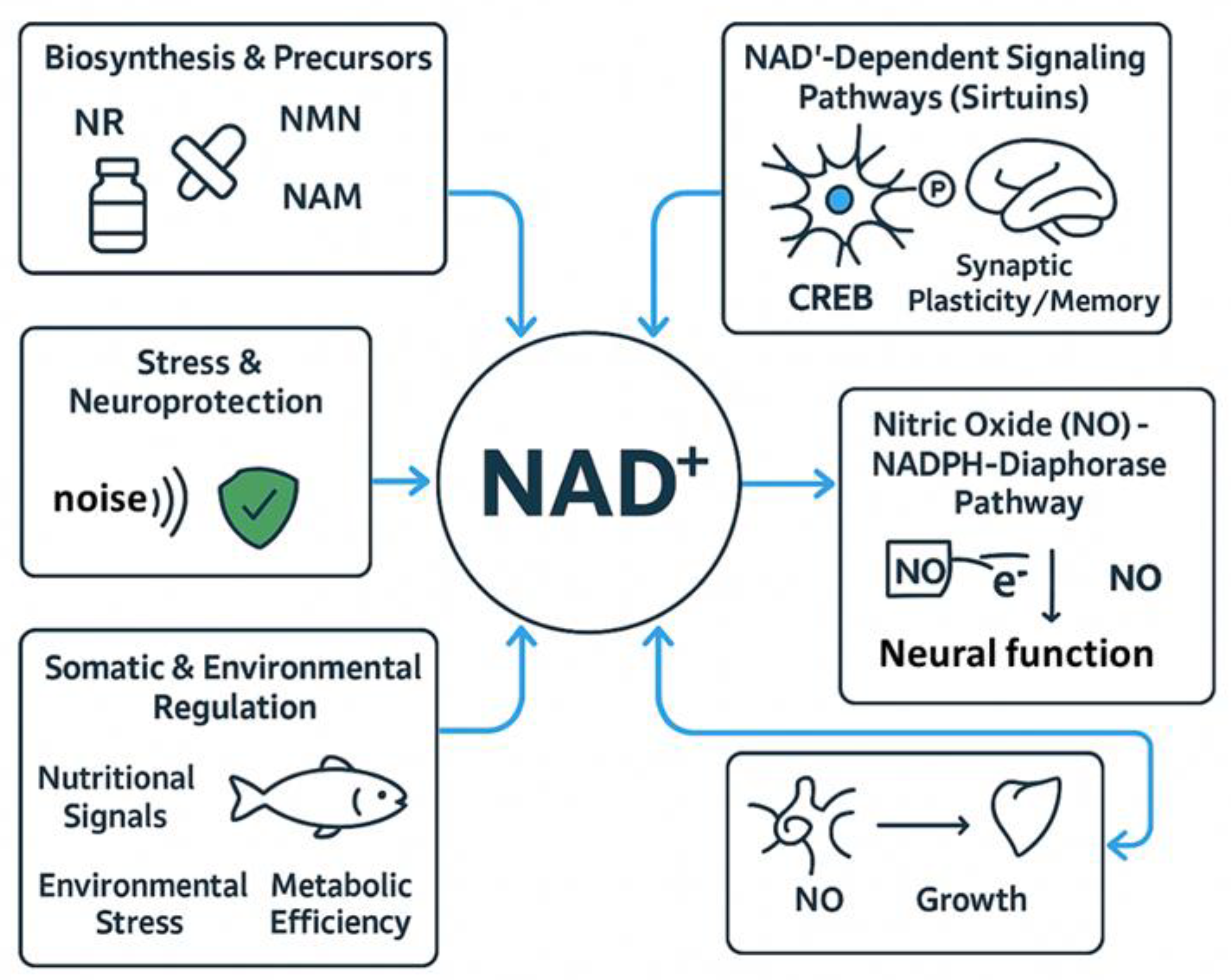

4. Nicotinamide and Related Metabolites in Fish

4.1. Core NAD⁺ Metabolism in Fish Nutrition

4.2. NAD+ and SIRTs as Molecular Hubs for Environmental Stress Adaptation in Fish

4.2.1. NAD+ Role in Stress Responses

| Species / Model | Stressor / Condition | Sirtuins (SIRT) involved | Main findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carp (Cyprinus carpio) |

Seasonal acclimatization (thermal cycles) | SIRT1 | Cold acclimation induced upregulation of rRNA biogenesis genes and DNA methylation changes at rDNA loci; SIRT1 linked environmental sensing to ribosomal synthesis | [68] |

| Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) | Cold acclimation | SIRT1, SIRT3 | Upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSP) HSP70/HSP90 and NAD+-dependent SIRTs; mitochondrial adaptation and proteostasis maintenance | [69] |

| Fish adipocytes (in vitro model) |

Hypoxia | SIRT2 | Hypoxia induced differential sirt2 expression; constrained adipocyte maturation and lipid metabolism | [70] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Stress (cortisol elevation) |

SIRT1 | Stress-induced cortisol suppressed sirt1 expression in hypothalamus; disrupted circadian clock and appetite-regulating peptides | [71] |

| Roughskin sculpin (Trachidermus fasciatus) | Osmotic stress | SIRT1 | Altered Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, caspase 3/7, and stress-related genes (sirt1, hsp70), apoptosis and cellular stress regulation | [72] |

| Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) | Temperature and ammonia stress | SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT5 | Tissue-specific expression changes under stress, regulating mitochondrial function and metabolic homeostasis | [73] |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Oxidative stress | SIRT1 | Dual regulation of p53 apoptosis: KAT8-dependent deacetylation (p53 K382) and KAT8-independent suppression of p53 transcription | [74] |

4.2.2. Disruption of NAD+-Dependent Pathways in Aquatic Organisms Exposed to Environmental Contaminants

| Fish species / Model | Contaminant / Stressor | Main affected pathway | Main findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chub (Leuciscus cephalus) |

Environmental pollutants (organochlorines, PAHs, heavy metals) | NAD⁺ metabolism / redox enzymes | Oxidative stress, metabolic enzyme disruption, pollutant-type dependent responses | [75] |

| Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) |

PCB 153 (Polychlorinated biphenyl 153) |

NAD⁺-linked energy metabolism | Brain proteome alterations, neurotoxicity risk | [76] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Bifenthrin (pesticide) | NAD⁺/NADH balance | Oxidative stress, endocrine disruption, salinity interaction | [77] |

| Rainbow trout (O. mykiss) |

Molybdo-flavoenzymes (AOX, XOR) | NAD⁺-dependent oxidoreduction | XOR exclusively NAD⁺-dependent, detoxification role | [79] |

| Crucian carp (Carassius carassius) | 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2) | NAD⁺ metabolism | Disrupted energy/redox homeostasis, endocrine disruption | [81] |

| Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Lufenuron & Flonicamide (pesticides) | NAD⁺-linked antioxidant/immune pathways | Altered antioxidant gene expression and immune response | [82] |

| Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) | Triclosan | NAD⁺/SIRT/Nrf2 signaling | Downregulated SIRT, impaired antioxidant defenses | [84] |

| Yellowstripe goby (Mugilogobius chulae) | Paracetamol | NAD⁺/SIRT/PXR pathway | SIRT1/3 activation, oxidative stress mitigation, xenobiotic defense | [86] |

| Yellowstripe goby | Atorvastatin | NAD⁺/SIRT/PXR pathway | Altered sirt1/3 expression, antioxidant/inflammatory regulation | [88] |

| Common carp | Triclocarban (TCC) | NAD⁺/SIRT3 / redox balance | Neutrophil extracellular traps formation via sirt3 inhibition, ROS accumulation | [90] |

| Atlantic cod | Wastewater treatment plant effluents | NAD⁺-SIRT / neuronal related genes | Transcriptomic disruption, impaired mitochondrial defense | [91] |

| EPC fish cells | Fluorene-9-bisphenol (Bisphenol A substitute) | NAD⁺/SIRT3 / mitophagy | Quercetin protection, restored mitochondrial homeostasis | [92] |

| Delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) | Ammonia | NAD⁺-redox pathways | Oxidative stress, metabolic resilience disruption | [93] |

| Common carp | Hydrogen peroxide | NAD⁺ redox/DNA repair | Neuronal oxidative damage, impaired NAD⁺ regeneration | [94] |

| Atlantic cod | Methylmercury | NAD⁺-linked mitochondrial pathways | Brain proteome disruption, neurotoxicity | [95] |

| Common carp | Cadmium | miR-217 / NAD⁺-SIRT1 axis | Immune dysregulation, NF-κB hyperacetylation | [96] |

| Fish (various, incl. Tachysurus sinensis) | Zinc (Zn) & Copper (Cu) | NAD⁺-SIRT1/3-autophagy | Zn activates lipophagy, Cu disrupts it, co-deficiency worsens steatosis | [97,98,99,100,101] |

| Crucian carp | ZnO nanoparticles | NAD⁺ redox / immune NETs | Oxidative stress, immune toxicity, NAD⁺ disruption | [98] |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) and Gibel carp (Carassius gibelio) |

Resveratrol (polyphenol) |

NAD⁺-SIRT1 / stress response | Enhanced antioxidant capacity, cold/ammonia stress protection | [102,103] |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Astilbin (flavonoid) | NAD⁺-SIRT1/Nrf2 | Protection against PCB126-induced apoptosis | [104] |

4.2.3. NAD+-sensitive mechanisms in fish metabolic adaptations: Insights for managing aquaculture-associated disorders

| Fish species | Main findings related to NAD⁺/SIRTUINS (SIRTs) metabolism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) |

Glucokinase-independent glucose sensing in liver and Brockmann bodies; metabolic regulation linked to NAD⁺-dependent SIRTs; suggests alternative nutrient-sensing pathways | [105] |

| Several fish species | Link between adipose triglyceride lipase, lipid metabolism, inflammation and NAD⁺ depletion; low NAD⁺ impairs SIRT1 activity affecting lipid metabolism and inflammation | [106] |

| Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) | Feeding restriction activates NAD⁺-dependent AMPK-SIRT1 pathway, suppressing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress, improving glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function | [107] |

| Large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) | n-3 PUFAs activate NAD⁺-SIRT1 pathway, reducing NF-κB-mediated inflammation, improving lipid metabolism and redox balance | [108] |

| Black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii), juvenile | Fenofibrate activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) /SIRT1 axis, enhancing fatty acid oxidation and reducing lipogenesis and inflammation, alleviating high-fat diet-induced hepatic dysfunction | [109] |

| Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) | SIRT1 regulates lipid catabolism, inhibits lipogenesis, and enhances antioxidant defenses via NAD⁺/SIRT1/FOXO1 (Forkhead Box O3a) signaling; upregulated under nutrient deprivation. | [111] |

| Black seabream | Betaine supplementation restores NAD⁺, activates SIRT1/ Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1 (SREBP-1)/PPARα pathway, reduces lipogenesis, enhances fatty acid oxidation, lowers inflammation, improves mitochondrial function. | [113] |

| Black seabream | SIRT1 protects against hepatic lipotoxicity through NAD⁺-dependent deacetylation of Ire1α, alleviating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lipid accumulation. | [114], [115] |

| Black seabream | Fucoidan activates SIRT1, modulating PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 axis, reducing ER stress, enhancing fatty acid oxidation, and improving redox homeostasis. | [117] |

5. NAD⁺ Metabolism and Neuromodulation in Fish: From Muscle Innervation to Cognitive Function

| Species / Model | Focus / Pathway | NAD⁺/NADPH Role | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), and eel (Anguilla anguilla) |

Neuromodulators & NADPH-diaphorase | NADPH as cofactor for nitric oxide (NO) production | Histochemical staining revealed NADPH-diaphorase activity in skeletal muscle nerves, linking NAD metabolism to NO-mediated neuromodulation of muscle function. | [118] |

| General vertebrate model | cAMP Response Element-Binding protein (CREB) transcription factor | Indirect NAD⁺/SIRT1 (sirtuin 1) regulation | CREB integrates extracellular signals into gene expression changes, regulating survival, metabolism, and circadian rhythms. | [119] |

| Goldfish (Carassius auratus) |

CREB in learning & memory | NAD⁺-SIRT1 regulation of CREB | Cognitive activity triggers CREB phosphorylation in memory-related brain areas; NAD⁺-SIRT1 likely modulates CREB-dependent plasticity. | [120] |

| Goldfish | miRNA-132/212 & fear memory | NAD⁺ in neuroplasticity & epigenetics | miRNAs regulate neuronal plasticity; altered NAD⁺ metabolism may affect memory formation and synaptic function. | [121] |

| Mediterranean farmed fish | Somatotropic axis & growth regulation | NAD⁺/SIRT1 metabolic regulation | Nutrition and environment modulate hepatic sirtuin activity; diet enhances NAD⁺-SIRT1 signaling, stress impairs growth via metabolic disruption. | [122] |

| Swordtail fish (Xiphophorus helleri) | NADPH-diaphorase atlas & escape reflex | NADPH as NOS cofactor | Mapped NADPH-d in Mauthner cells; linked NADPH-dependent NO signaling to escape reflex pathways. | [123] |

| Dogfish (Triakis scyllia) |

Vagal afferent NADPH-d activity | NADPH in sensory NO signaling | NADPH-d in vagal afferents suggests NADPH-dependent NO production in sensory/autonomic pathways. | [124] |

| Cichlid (Tilapia mariae) |

NADPH-d in central nervous system | NADPH in neural development | Histochemistry showed NADPH-d activity essential for NO-mediated maturation of neuronal pathways. | [125] |

| African cichlid (Haplochromis burtoni) | Brain regional NADPH-d mapping | NADPH turnover from NAD⁺ | Enrichment in entopeduncular nucleus suggests localized NAD⁺/NADP⁺ demand for NO signaling. | [126] |

| Goldfish (Carassius auratus) |

Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and NADPH-d distribution | NADPH as cofactor for NO | Broad distribution in brain regions for sensory, motor, and neuroendocrine regulation. | [127] |

| Grass puffer (Takifugu niphobles) | NOS in branchial innervation | NADPH-dependent (NOS) activity | NOS activity in glossopharyngeal/vagal afferents links NAD⁺ metabolism to vascular regulation in gills. | [128] |

| Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) | NAD⁺ in acoustic stress response | NAD⁺/NADH redox in auditory stress | Genes linked to NAD⁺ metabolism and oxidative stress protect auditory tissues from loud sound damage. | [129] |

6. Dietary Interventions and NAD+ Homeostasis: Implications for Fish Health and Product Quality

| Fish species | Supplements/Context | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) |

Sirtuins (SIRTs), genes & fasting | Fasting upregulated hepatic sirt1/sirt3, showing NAD+-dependent roles in nutrient deprivation. SIRT functions tissue-specific, with gene duplications suggesting subfunctionalization. | [130] |

| Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) | Mulberry leaf meal | Dietary supplementation (6–9%) enhanced growth, feed efficiency, antioxidant capacity, and immune genes. Likely influences NAD+-dependent SIRT-mediated regulation. | [131] |

|

Gilthead seabream |

Chitosan-tripolyphosphate-DNA nanoparticles | Gene delivery enhanced carbohydrate-to-lipid conversion; NAD+/NADH and NADPH involved in lipogenesis. Suggests central role of NADPH-dependent pathways in lipid biosynthesis | [132] |

|

Tilapia GIFT (Oreochromis niloticus) |

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) supplementation | Leucine/valine enhanced growth, glycolipid metabolism, immune function via NAD+-SIRT1/AMPK pathways. Improved insulin sensitivity, antioxidant capacity, and disease resistance | [133] |

|

Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) |

Niacin deficiency | Deficiency caused poor flesh quality, glycolysis increase, mitochondrial dysfunction. Niacin is a precursor for NAD+/NADP+, essential for energy metabolism | [134] |

| Meagre (Argyrosomus regius) and gilthead seabream |

Fish by-products | By-products rich in niacin, tryptophan, proteins – contribute to NAD+ biosynthesis via de novo/salvage pathways. Implications for aquafeeds and functional foods | [135] |

|

Wuchang bream |

NAD⁺ precursors (hyperglycemia) | NA, NAM, NR, NMN tested against high-glucose damage. NR most effective: restored NAD+, activated SIRT1/SIRT3, reduced oxidative stress/inflammation, improved glucose metabolism | [138] |

|

Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) |

Zophobas atratus larval meal | Replacing soybean meal improved flavor quality and energy metabolism. Enhanced NADH, acetyl-CoA, ATP, fatty acid accumulation; increased umami compounds, reduced off-flavors | [143] |

|

Zig-zag eel (Mastacembelus armatus) |

Spirulina supplementation and Aeromonas hydrophila infection | Improved liver immune/metabolic responses under infection. Likely acts through NAD-dependent enzymes (SIRTs, PARPs) regulating oxidative stress and inflammation | [144] |

|

Killifish (Nothobranchius guentheri) |

Resveratrol in reproductive aging |

Activated NAD+/SIRT1 axis, reduced inflammation, improved lipid metabolism, delayed ovarian aging. Highlighted role of SIRT1 in gut senescence, hepatic steatosis, and reproduction | [145] |

|

Nile tilapia |

Resveratrol |

Improved hepatic lipid metabolism in red tilapia by activating NAD+/SIRT1/AMPK signaling, enhancing lipolysis, and suppressing lipogenesis | [146] |

| Killifish |

Resveratrol in short-lived fish | Delayed ovarian aging | [147] |

|

Black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) |

Arachidonic acid |

Optimal 0.76% diet improved growth, lipid metabolism via SIRT1 activation. Promoted FA oxidation, reduced lipogenesis/oxidative stress. Linked NAD+ pathways with eicosanoid signaling | [148] |

|

Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) |

Vitamin K3 + nicotinamide |

VK3 + nicotinamide improved growth, antioxidant capacity, tissue composition. Nicotinamide component supports NAD+ salvage pathway and redox balance | [149] |

7. NAD⁺ Related Metabolites and Their Implications in Fish Skin

| Fish species | Context | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) |

Wild-type vs yellow mutant |

Transcriptome analysis revealed NAD+ADP-ribosyltransferase activity and NAD biosynthetic processes enriched |

[150] |

|

Blass bloched rockfish (Sebastes pachycephalus) |

Skin pigmentation |

Nicotinamide Riboside Kinase 2 (NMRK2) differentially expressed across skin color types; involved in NAD biosynthesis. Suggests NAD pathways affect pigmentation via cellular energy metabolism | [153] |

|

Cichlids |

Aquaculture implications of pigmentation | Skin coloration linked to marketability, health indicators, selective breeding, mate selection, and survival. NAD+-related genes (e.g., NMRK2) influence pigmentation processes | [155] |

8. NAD⁺ Metabolism in Fish: Implications For Immune Defense and Cellular Homeostasis

| Fish species | Context | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus) |

Bacterial infection (Vibrio sp.) |

Metabolomic profiling revealed alterations in NAD+-dependent pathways, affecting redox balance and energy metabolism | [157] |

| Large yellow croakers (Pseudosciaena crocea) | Aptamers and bacterial infection (Pseudomonas plecoglossicida) | Aptamer B4 inhibits pathogen; transcriptomic shifts involve NAD+/NADH redox reactions; potential therapeutic targets in NAD-dependent processes | [160] |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Viral infection (IRF9, interferon regulator factor 9) | IRF9 inhibits SIRT1, enhances p53 acetylation & apoptosis; demonstrates trade-off between metabolic regulation and immune defense | [161] |

| Killifish (Nothobranchius guentheri) |

Metformin and Poly I:C | Metformin attenuates gut aging via NAD+-dependent AMP-activated protein kinase activation; reduces inflammation, oxidative stress, enhances mitochondrial function | [163] |

| Chinese perch (Siniperca chuatsi) |

Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) in antiviral defense | SIRT6 enhances interferon-stimulated genes; viral infections increase NAD+; highlights SIRT6 role in NAD+-dependent antiviral defense | [164] |

| Grouper hybrid (Epinephelus fuscogutatus × Epinephelus lanceolatus) | Parasite resistance | Transcriptomic analysis revealed NAD+-dependent enzymes involved in immune signaling and redox balance, contributing to parasite resistance | [165] |

9. NAD⁺ Influence in Fish Eggs and Declining in Muscle Post-Mortem

10. Concluding Remarks and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katsyuba, E.; Romani, M.; Hofer, D.; Auwerx, J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat Metab. 2020, 2, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtkooper, R. H.; Cantó, C.; Wanders, R. J.; Auwerx, J. The secret life of NAD+ is an old metabolite that controls new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, A.; Liu, L.; Chellappa, K.; Redpath, P.; Nakamaru-Ogiso, E.; Paolella, L. M.; Zhang, Z.; Migaud, M. E.; Rabinowitz, J. D.; Baur, J. A. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is transported into the mammalian mitochondria. eLife 2018, 7, e33246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarow, W.; Stollar, B.D. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase, a non-histone chromatin protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1977, 180, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C.; Niere, M.; Ziegler, M. The NMN/NaMN adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) protein family. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 2009, 14, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Qiu, F.; Li, Y.; Che, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, S. Mechanisms of the NAD+ salvage pathway in enhancing skeletal muscle function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1464815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgaldi, S.; Kahmini, F.R. A comprehensive review of Sirtuins: With a major focus on redox homeostasis and metabolism. Life Sci. 2021, 282, 119803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins regulate metabolism and health. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannous, C.; Booz, G.W.; Altara, R.; Muhieddine, D.H.; Mericskay, M.; Refaat, M.M.; Zouein, F.A. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide: biosynthesis, consumption, and therapeutic roles in cardiac diseases. Acta Physiol. 2021, 231, e13551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariani, K.; Menzies, K.J.; Ryu, D.; Wegner, C.J.; Wang, X.; Ropelle, E.R.; Moullan, N.; Zhang, H.; Perino, A.; Lemos, V.; Kim, B.; Park, Y.K.; Piersigilli, A.; Pham, T.X.; Yang, Y.; Ku, C.S.; Koo, S.I.; Fomitchova, A.; Cantó, C.; Schoonjans, K.; Sauve, A.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Auwerx, J. Eliciting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide repletion reverses fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, G.; Reinke, H.; Altmeyer, M.; Gutierrez-Arcelus, M.; Hottiger, M. O.; Schibler, U. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in phase entrainment of circadian clocks during feeding. Cell 2010, 142, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Sharf, R.; Alam, M.; Sharf, Y.; Usmani, N. Chronotherapeutic and epigenetic regulation of circadian rhythms: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-sirtuin axis. J. Sleep Med. 2024, 21, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Milbrandt, J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevented axonal degeneration. Science 2004, 305, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mohammed, F. S.; Zhang, N.; Sauve, A. A. Dihydronicotinamide riboside is a potent NAD+ concentration enhancer both in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 9295–9307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Zhang, C.; Luo, T.; Vyas, A.; Chen, S. H.; Liu, C.; Kassab, M. A.; Yang, Y.; Kong, M.; Yu, X. NADP+ is an endogenous PARP inhibitor involved in DNA damage response and tumor suppression. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsyuba, E.; Mottis, A.; Zietak, M.; De Franco, F.; van der Velpen, V.; Gariani, K.; Ryu, D.; Cialabrini, L.; Matilainen, O.; Liscio, P.; Giacchè, N.; Stokar-Regenscheit, N.; Legouis, D.; de Seigneux, S.; Ivanisevic, J.; Raffaelli, N.; Schoonjans, K.; Pellicciari, R.; Auwerx, J. De novo NAD+ synthesis enhances mitochondrial function and improves health. Nature 2018, 563, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, C.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Youn, D.Y.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Cen, Y.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Yamamoto, H.; Andreux, P.A.; Cettour-Rose, P.; et al. The NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Pitta, M.; Jiang, H.; Lee, J.H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Kawamoto, E.M.; Mattson, M.P. Nicotinamide forestalls pathology and cognitive decline in Alzheimer mice: Evidence for improved neuronal bioenergetics and autophagy progression. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1564–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Byun, J.; Zhai, P.; Ikeda, Y.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, an intermediate of NAD+ synthesis, protects the heart from ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS One 2014, 9, e98972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Auranen, M.; Paetau, I.; Pirinen, E.; Euro, L.; Forsström, S.; Pasila, L.; Velagapudi, V.; Carroll, C.J.; Auwerx, J.; Suomalainen, A. Effective treatment of mitochondrial myopathy by nicotinamide riboside and vitamin B3. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morigi, M.; Perico, L.; Rota, C.; Longaretti, L.; Conti, S.; Rottoli, D.; Novelli, R.; Remuzzi, G.; Benigni, A. Sirtuin 3-dependent mitochondrial dynamic improvements protect against acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariani, K.; Menzies, K.J.; Ryu, D.; Wegner, C.J.; Wang, X.; Ropelle, E.R.; Moullan, N.; Zhang, H.; Perino, A.; Lemos, V.; et al. Eliciting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide repletion reverses fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdin, E. NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 2015, 350, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, S.; Nisar, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Shah, A.R.; Frenneaux, M.P.; Fakhro, K.; Haris, M.; Reddy, R.; Patay, Z.; Baur, J.; et al. Role of NAD+ in regulating cellular and metabolic signaling pathways. Mol. Metab. 2021, 49, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J.; Choi, J.M.; Kim, L.; Park, S.E.; Rhee, E.J.; Lee, W.Y.; Oh, K.W.; Park, S.W.; Park, C.Y. Nicotinamide improves glucose metabolism and affects the hepatic NAD-sirtuin pathway in a rodent model of obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, C. NAD+ Precursors: A questionable redundancy. Metabolites 2022, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trammell, S.A.J.; Schmidt, M.S.; Weidemann, B.J.; Redpath, P.; Jaksch, F.; Dellinger, R.W.; Li, Z.; Abel, E.D.; Migaud, M.E.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegre, G.F.S.; Pastore, G.M. NAD+ precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR), are potential dietary contributors to health. Curr Nutr Rep. 2023, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhassan, Y.S.; Kluckova, K.; Fletcher, R.S.; Schmidt, M.S.; Garten, A.; Doig, C.L.; Cartwright, D.M.; Oakey, L.; Burley, C.V.; Jenkinson, N.; Wilson, M.; Lucas, S.J.E.; Akerman, I.; Seabright, A.; Lai, Y.C.; Tennant, D.A.; Nightingale, P.; Wallis, G.A.; Manolopoulos, K.N.; Brenner, C.; Lavery, G.G. Nicotinamide riboside augments the human skeletal muscle NAD+ metabolome and induces transcriptomic and anti-inflammatory signatures in aged subjects: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1717–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollerup, O.L.; Christensen, B.; Svart, M.; Schmidt, M.S.; Sulek, K.; Ringgaard, S.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Møller, N.; Brenner, C.; Treebak, J.T.; Jessen, N. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: safety, insulin sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrador, E.; Salvador-Palmer, R.; Pellicer, B.; López-Blanch, R.; Sirerol, J.A.; Villaescusa, J.I.; Montoro, A.; Dellinger, R.W.; Estrela, J.M. The combination of natural polyphenols with a precursor of NAD+ and a TLR2/6 ligand lipopeptide protects mice against lethal γ-radiation. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 45, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, S.E.; Khosla, S.; Baur, J.A.; de Cabo, R.; Musi, N. Drugs targeting mechanisms of aging to delay age-related disease and promote health span: Proceedings of a National Institute on Aging Workshop. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, A.; Guan, X.; Ying, T.; Pan, J.; Tan, M.; Lu, J. An updated review on the mechanisms, pre-clinical and clinical comparisons of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotinamide Riboside (NR). Food Front. 2024, 6, 630–643. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, A.; Stainier, D.Y.R. Lessons from "lower" organisms: What worms, flies, and zebrafish can teach us about human energy metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Prisingkorn, W.; Prathomya, P.; Jakovlic, I.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, W.M. Transcriptomics, metabolomics and histology indicate that high-carbohydrate diet negatively affects the liver health of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.; Ninov, N. Catching new targets in metabolic disease with a zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 2017, 37, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, L.; Maddison, L.A.; Chen, W. Zebrafish as a model for obesity and diabetes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaoka, Y.; Terai, S.; Sakaida, I.; Nishina, H. The expanding role of fish models in understanding non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Zang, L.; Hirano, M.; Shimada, Y.; Wang, Z.; Umemoto, N.; Kuroyanagi, J.; Nishimura, N.; Tanaka, T. Diet-induced obesity in zebrafish shares common pathophysiological pathways with mammalian obesity. BMC Physiol. 2010, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goody, M.F.; Kelly, M.W.; Lessard, K.N.; Khalil, A.; Henry, C.A. Nrk2b-mediated NAD+ production regulates cell adhesion and is required for muscle morphogenesis in vivo: Nrk2b and NAD+ in muscle morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2010, 344, 809–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goody, M.F.; Henry, C.A. A need for NAD+ in muscle development, homeostasis, and aging. Skeletal Muscle 2018, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goody, M.F.; Kelly, M.W.; Reynolds, C.J.; Khalil, A.; Crawford, B.D.; Henry, C.A. NAD+ biosynthesis ameliorates a zebrafish model of muscular dystrophy. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Ying, L.; Li, L.; Yan, Q.; Yi, W.; Ying, C.; Wu, H.; Ye, X. Resveratrol ameliorates diet-induced dysregulation of lipid metabolism in zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS One 2017, 12, e0180865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.C.; Gregório, C.; Uribe-Cruz, C.; Guizzo, R.; Malysz, T.; Faccioni-Heuser, M.C.; Longo, L.; da Silveira, T.R. Chronic exposure to ethanol causes steatosis and inflammation in zebrafish liver. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Kim, S.H. Adult zebrafish as an in vivo drug-testing model for ethanol-induced acute hepatic injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Morcillo, F.J.; Cantón-Sandoval, J.; Martínez-Navarro, F.J.; Cabas, I.; Martínez-Vicente, I.; Armistead, J.; Hatzold, J.; López-Muñoz, A.; Martínez-Menchón, T.; Corbalán-Vélez, R.; Lacal, J.; Hammerschmidt, M.; García-Borrón, J.C.; García-Ayala, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Pérez-Oliva, A.B.; García-Moreno, D.; Mulero, V. NAMPT-derived NAD+ fuels PARP1 to promote skin inflammation via parthanatos. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Hao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ringø, E.; Olsen, R.E.; Clarke, J.L.; Ran, C.; Zhou, Z. Propionate induces intestinal oxidative stress via Sod2 propionylation in zebrafish. iScience. 2021, 24, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, L.; Wong, L. β-Nicotinamide mononucleotide supplement with astaxanthin and blood orange enhanced NAD+ bioavailability and mitigated age-associated physiological decline in zebrafish. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, X.; Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in decabromodiphenyl ethane-induced lipid metabolism disorders and neurotoxicity in zebrafish larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 11043–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandaram, A.; Paul, J.; Wankhar, W.; Thakur, A.; Verma, S.; Vasudevan, K.; Wankhar, D.; Kammala, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Jaganathan, R.; Iyaswamy, A.; Rajan, R. Aspartame causes developmental defects and teratogenicity in zebrafish embryo: Role of impaired SIRT1/FOXO3a axis in neuron cells. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurho, V.; Gilliland, C.; Ensing, J.; Vansickle, E.; Lanning, N.J.; Mark, P.R.; Grainger, S. A zebrafish model of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) deficiency-derived congenital disorders. Preprint https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387907417 [accessed Aug 06 2025]. 2025.

- Xu, H.; Mao, X.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Jiang, S.; Cai, L.; Miao, X.; Tao, Y.; Peng, C.; Lv, M.; Li, Y. Perfluorooctanoic acid triggers premature ovarian insufficiency by impairing NAD+ synthesis and mitochondrial function in adult zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 201, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Xie, S.; Wang, M.; Guan, G.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X. Identification and functional characterization of a novel PRPS1 variant in X-linked nonsyndromic hearing loss: Insights from zebrafish and cellular models. Hum. Mutat. 2025, 2025, 6690588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xian, C.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, H.; Lv, Z.; Liu, J. Nicotinamide riboside ameliorates survival time and motor dysfunction in an MPTP-Induced Parkinson's disease zebrafish model through effects on glucose metabolism and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 399, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raas, Q.; Haouy, G.; de Calbiac, H.; Pasho, E.; Marian, A.; Guerrera, I.C.; Rosello, M.; Oeckl, P.; Del Bene, F.; Catanese, A.; Ciura, S.; Kabashi, E. TBK1 is involved in programmed cell death and ALS-related pathways in novel zebrafish models. Cell Death Discovery 2025, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimeno, S.; Saida, Y.; Tabata, T. Response of hepatic NAD- and NADP-isocitrate dehydrogenase activities to several dietary conditions in fishes. Nippon Suisan Gakk. 1996, 62, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carafa, V.; Rotili, D.; Forgione, M.; Cuomo, F.; Serretiello, E.; Hailu, G.S.; Jarho, E.; Lahtela-Kakkonen, M.; Mai, A.; Altucci, L. Sirtuin functions and modulation: from chemistry to the clinic. Clin Epigenetics 2016, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabiljo, J.; Murko, C.; Pusch, O.; Zupkovitz, G. Spatio-temporal expression profile of sirtuins during aging of the annual fish Nothobranchius furzeri. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2019, 33, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jia, E.; Shi, H.; Li, X.; Jiang, G.; Chi, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D. Selection of reference genes for miRNA quantitative PCR and its application in miR-34a/Sirtuin-1 mediated energy metabolism in Megalobrama amblycephala. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 45, 1663–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Mirabet, P.; Perera, E.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Local DNA methylation helps to regulate muscle sirtuin 1 gene expression across seasons and advancing age in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Front. Zool. 2020, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Mirabet, P.; Naya-Català, F.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. The expansion of sirtuin gene family in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Phylogenetic, syntenic, and functional insights across the vertebrate/fish lineage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zou, J.; Zhao, J.; Chen, A. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the SIRT gene family in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics. 2025, 54, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qi, Y.; Liang, Q.; et al. The chimeric genes in the hybrid lineage of Carassius auratus cuvieri (♀) × Carassius auratus red var. (♂). Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 6, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, S. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (Nampt) of hybrid crucian carp protects intestinal barrier and enhances host immune defense against bacterial infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2022, 128, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.J.; Volkoff, H. The role of visfatin / NAMPT in the regulation of feeding in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Peptides 2023, 160, 170919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, C.; Librán-Pérez, M.; Otero-Rodiño, C.; López-Patiño, M.A.; Míguez, J.M.; Soengas, J.L. Ceramides are involved in the regulation of food intake in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol. 2016, 311, R658–R668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnicombe, K.R.T.; Volkoff, H. Possible role of transcription factors (BSX, NKX2.1, IRX3 and SIRT1) in the regulation of appetite in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2022, 268, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, E.N.; Zuloaga, R.; Nardocci, G.; Fernandez de la Reguera, C.; Simonet, N.; Fumeron, R.; Valdes, J.A.; Molina, A.; Alvarez, M. Skeletal muscle plasticity induced by seasonal acclimatization in carp involves differential expression of rRNA and molecules that epigenetically regulate its synthesis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 172-173, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teigen, L.E.; Orczewska, J.I.; McLaughlin, J.; O'Brien, K.M. Cold acclimation increases levels of some heat shock protein and sirtuin isoforms in threespine stickleback. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 188, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekambaram, P.; Parasuraman, P. Differential expression of sirtuin 2 and adipocyte maturation restriction: an adaptation process during hypoxia in fish. Biol Open. 2017, 6, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, F.; Hernández-Pérez, J.; Chivite, M.; Soengas, J.L.; Míguez, J.M.; López-Patiño, M.A. Involvement of cortisol and sirtuin1 during the response to stress of hypothalamic circadian system and food intake-related peptides in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 1122–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Kuang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, A.; Feng, W.; Zhuang, Z. Effects of osmotic stress on Na<sup>+</sup>/K<sup>+</sup>-ATPase, caspase 3/7 activity, and the expression profiling of sirt1, hsf1, and hsp70 in the roughskin sculpin (Trachidermus fasciatus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Miao, L.; Abba, B.S.A.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, S.; Luo, C.; Liu, B.; Ge, X. Molecular characterization and expression of sirtuin 2, sirtuin 3, and sirtuin 5 in the Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) in response to acute temperature and ammonia nitrogen stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 252, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wu, C.; Li, D.; Mao, H.; Kong, L.; Hu, C.; Xu, X. Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) deacetylase SIRT1 targets p53 to suppress apoptosis in a KAT8 dependent or independent manner. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 144, 109264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machala, M.; Dusek, L.; Hilscherová, K.; Kubínová, R.; Jurajda, P.; Neca, J.; Ulrich, R.; Gelnar, M.; Studnicková, Z.; Holoubek, I. Determination and multivariate statistical analysis of biochemical responses to environmental contaminants in feral freshwater fish Leuciscus cephalus, L. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001, 20, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K.; Puntervoll, P.; Klungsøyr, J.; Goksøyr, A. Brain proteome alterations of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) exposed to PCB 153. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 105, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riar, N.; Crago, J.; Jiang, W.; Maryoung, L.A.; Gan, J.; Schlenk, D. Effects of salinity acclimation on the endocrine disruption and acute toxicity of bifenthrin in freshwater and euryhaline strains of Oncorhynchus mykiss. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 2779–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garattini, E.; Mendel, R.; Romão, M.J.; Wright, R.; Terao, M. Mammalian molybdo-flavoenzymes, an expanding family of proteins: structure, genetics, regulation, function and pathophysiology. Biochem. J. 2003, 372, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburas, O.A. Investigation of aldehyde oxidase and xanthine oxidoreductase in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Doctoral Thesis, University of Huddersfield. 2014. Available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/23543/.

- Almeida, Â.; Silva, M.G.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Freitas, R. Concentrations levels and effects of 17alpha-Ethinylestradiol in freshwater and marine waters and bivalves: A review. Environ. Res. 2020, 185, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Zuo, C. Responses in the crucian carp (Carassius auratus) exposed to environmentally relevant concentration of 17α-Ethinylestradiol based on metabolomics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 183, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri Mirghaed, A.; Baes, M.; Hoseini, S.M. Humoral immune responses and gill antioxidant-related gene expression of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to lufenuron and flonicamide. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska-Trypuć, A. A review on triclosan in wastewater: Mechanism of action, resistance phenomenon, environmental risks, and sustainable removal techniques. Water Environ Res. 2023, 95, e10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; He, C.; Ku, P.; Xie, M.; Lin, J.; Lu, S.; Nie, X. Effects of triclosan on the RedoximiRs/Sirtuin/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 230, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. Paracetamol in the environment and its degradation by microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinan, X.; Yimeng, W.; Chao, W.; Tianli, T.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Xiangping, N. Response of the Sirtuin/PXR signaling pathway in Mugilogobius chulae exposed to environmentally relevant concentration Paracetamol. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 249, 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Ponce-Canchihuamán, J. Emerging various environmental threats to brain and overview of surveillance system with zebrafish model. Toxicol. Rep. 2017, 4, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xie, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Nie, X. Effects of atorvastatin on the Sirtuin/PXR signaling pathway in Mugilogobius chulae. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 60009–60022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, D.; Catalano, A.; Ceramella, J.; Saturnino, C.; Salvagno, L.; Ielo, I.; Drommi, D.; Scali, E.; Plutino, M.R.; Rosace, G.; Sinicropi, M.S. The Different facets of triclocarban: A review. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, M.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X. Triclocarban evoked neutrophil extracellular trap formation in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) by modulating SIRT3-mediated ROS crosstalk with ERK1/2/p38 signaling. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 129, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, J.T.; Sydnes, M.O.; Ræder, E.M.; Schlenk, D.; Pampanin, D.M. Transcriptomic profiles of brains in juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) exposed to pharmaceuticals and personal care products from a wastewater treatment plant discharge. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xing, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, T. Unraveling the mechanism of quercetin alleviating BHPF-induced apoptosis in epithelioma papulosum cyprini cells: SIRT3-mediated mitophagy. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connon, R.E.; Deanovic, L.A.; Fritsch, E.B.; D'Abronzo, L.S.; Werner, I. Sublethal responses to ammonia exposure in the endangered delta smelt; Hypomesus transpacificus (Fam. Osmeridae). Aquat Toxicol. 2011, 105, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Du, J.; Cao, L.; Feng, W.; He, Q.; Xu, P.; Yin, G. Application of transcriptome analysis to understand the adverse effects of hydrogen peroxide exposure on brain function in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.; Puntervoll, P.; Valdersnes, S.; Goksøyr, A. Responses in the brain proteome of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) exposed to methylmercury. Aquat Toxicol. 2010, 100, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Di, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Kong, X. miR-217 through SIRT1 regulates the immunotoxicity of cadmium in Cyprinus carpio. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 248, 109086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Hogstrand, C.; Chen, G.; Lv, W.; Song, Y.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Z. Zn Induces lipophagy via the deacetylation of beclin1 and alleviates Cu-induced lipotoxicity at their environmentally relevant concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4943–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Wu, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, P.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Z. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) exhibit immune toxicity to crucian carp (Cyprinus carpio). by neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) release and oxidative stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 129, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.P.; Kaushik, S. Nutrition and metabolism of minerals in fish. Animal (Basel) 2021, 11, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemann, R.; Dick, J.G.; Klaverkamp, J.F. Metallothionein estimates in marine mammal and fish tissues by three methods: 203Hg displacement, polarography and metal-Summation. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1994, 54, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.C.; Zhang, X.; Pantopoulos, K.; Song, C.C.; Yang, H.; Wei, X.L.; Luo, Z. Mitochondrial oxidative stress inhibited Sirt3/Foxo3/PPARα pathway and aggravated copper and zinc co-deficiency-induced hepatic lipotoxicity in a fish model. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Peng, H.W.; Hseu, J.R.; Wu, G.C.; Chang, C.F.; Tseng, Y.C. Resveratrol induces expression of metabolic and antioxidant machinery and protects tilapia under cold stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, Q.; Dong, B.; Han, D.; Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Xie, S.; Jin, J. Resveratrol attenuated oxidative stress and inflammatory and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by acute ammonia exposure in gibel carp (Carassius gibelio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 251, 114544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, B.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, S.; Li, S. Astilbin targeted Sirt1 to inhibit acetylation of Nrf2 to alleviate grass carp hepatocyte apoptosis caused by PCB126-induced mitochondrial kinetic and metabolism dysfunctions. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 141, 109000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Rodiño, C.; Librán-Pérez, M.; Velasco, C.; Álvarez-Otero, R.; López-Patiño, M.A.; Míguez, J.M.; Soengas, J.L. Glucosensing in liver and Brockmann bodies of rainbow trout through glucokinase-independent mechanisms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 199, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.J.; Liu, W.B.; Li, X.F.; Zhou, M.; Xu, C.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, G.Z. Molecular cloning of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) gene from blunt snout bream and its expression after LPS-induced TNF-α factor. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 44, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, W.B.; Remø, S.C.; Wang, B.K.; Shi, H.J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.D.; Li, X.F. Feeding restriction alleviates high carbohydrate diet-induced oxidative stress and inflammation of Megalobrama amblycephala by activating the AMPK-SIRT1 pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, B.; Ji, R.; Xu, W.; Mai, K.; Ai, Q. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids alleviate hepatic steatosis-induced inflammation through Sirt1-mediated nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 subunit in hepatocytes of large yellow croaker (Larmichthys crocea). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 71, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Dhiman, S.; Gupta, G.D.; Asati, V. An investigative review for pharmaceutical analysis of fenofibrate. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2023, 61, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Zhu, T.; Tocher, D.R.; Luo, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Pan, T.; Yuan, Y.; Betancor, M.B.; Jiao, L.; Sun, P.; Zhou, Q. Dietary fenofibrate attenuated high-fat-diet-induced lipid accumulation and inflammation response partly through regulation of pparα and sirt1 in juvenile black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020, 109, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Chen, N.; Li, S. Molecular cloning and characterization of sirtuin 1 and its potential regulation of lipid metabolism and antioxidant response in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 726877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.K.; Paal, M.C.; Donohue, T.M. Jr.; Ganesan, M.; Osna, N.A.; Kharbanda, K.K. Beneficial effects of betaine: A comprehensive review. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Shen, Y.; Pan, T.; Zhu, T.; Li, X.; Xu, F.; Betancor, M.B.; Jiao, L.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q. Dietary betaine mitigates hepatic steatosis and inflammation induced by a high-fat-diet by modulating the Sirt1/Srebp-1/Pparɑ pathway in juvenile black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegeli). Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 694720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymundo, D.P.; Doultsinos, D.; Guillory, X.; Carlesso, A.; Eriksson, L.A.; Chevet, E. Pharmacological targeting of IRE1 in cancer. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Shen, Y.; Monroig, Ó.; Zhao, W.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, T.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q. Sirt1 mitigates hepatic lipotoxic injury induced by high-fat-diet in fish through Ire1α deacetylation. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 3210–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthuli, S.; Wu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wu, M.; Tong, H. Therapeutic effects of fucoidan: A review on recent studies. Mar. Drugs. 2019, 17, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Shen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Monroig, Ó.; Zhu, T.; Sun, P.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, M. Fucoidan alleviates hepatic lipid deposition by modulating the Perk-Eif2α-Atf4 axis via Sirt1 activation in Acanthopagrus schlegelii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, G.; Domeneghini, C.; Arrighi, S.; Mascarello, F.; Veggetti, A. Different putative neuromodulators are present in the nerves which distribute to the teleost skeletal muscle. Histol. Histopathol. 1998, 13, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Lazarovici, P.; Quirion, R.; Zheng, W. cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB): A possible signaling molecule link in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.E.; Thangaleela, S.; Balasundaram, C. Spatial learning associated with stimulus response in goldfish Carassius auratus: relationship to activation of CREB signalling. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 41, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaleela, S.; Shanmugapriya, V.; Mukilan, M.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Rajan, K.E. Alterations in MicroRNA-132/212 expression impairs fear memory in goldfish Carassius auratus. Ann. Neurosci. 2018, 25, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Simó-Mirabet, P.; Naya-Català, F.; Martos-Sitcha, J.A.; Perera, E.; Bermejo-Nogales, A.; Benedito-Palos, L.; Calduch-Giner, J.A. Somatotropic axis regulation unravels the differential effects of nutritional and environmental factors in growth performance of marine farmed fishes. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anken, R.H.; Rahmann, H. An atlas of the distribution of NADPH-diaphorase in the brain of the highly derived swordtail fish Xiphophorus helleri (Atherinoformes: Teleostei). J. Hirnforsch. 1996, 37, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Funakoshi, K.; Kadota, T.; Atobe, Y.; Goris, R.C.; Kishida, R. NADPH-diaphorase activity in the vagal afferent pathway of the dogfish, Triakis scyllia. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 237, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, L. Development of NADPH-diaphorase activity in the central nervous system of the cichlid fish, Tilapia mariae. Brain Behav. Evol. 1999, 54, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhao, A.G.; Malz, C.R. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-diaphorase activity in the brain of a cichlid fish, with remarkable findings in the entopeduncular nucleus: a histochemical study. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2004, 27, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldez-Perez, R.M.; Gaytan, S.P.; Ruano, D.; Torres, B.; Pasaro, R. Distribution of NADPH-diaphorase and nitric oxide synthase reactivity in the central nervous system of the goldfish (Carassius auratus). J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2008, 35, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, K.; Kadota, T.; Atobe, Y.; Nakano, M.; Goris, R.C.; Kishida, R. Nitric oxide synthase in the glossopharyngeal and vagal afferent pathway of a teleost, Takifugu niphobles. The branchial vascular innervation. Cell Tissue Res. 1999, 298, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.D.; Payne, J.F.; Rise, M.L. Identification of a gene set to evaluate the potential effects of loud sounds from seismic surveys on the ears of fishes: a study with Salmo salar. J. Fish Biol. 2014, 84, 1793–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Mirabet, P.; Bermejo-Nogales, A.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Tissue-specific gene expression and fasting regulation of sirtuin family in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lin, Y.; Qian, L.; Miao, L.; Liu, B.; Ge, X.; Shen, H. Mulberry leaf meal: A potential feed supplement for juvenile Megalobrama amblycephala "Huahai No. 1". Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 128, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Marrero, J.I.; Villasante, J.; Rashidpour, A.; Palma, M.; Fàbregas, A.; Almajano, M.P.; Viegas, I.; Jones, J.G.; Miñarro, M.; Ticó, J.R.; Baanante, I.V.; Metón, I. The administration of chitosan-tripolyphosphate-DNA nanoparticles to express exogenous SREBP1a enhances conversion of dietary carbohydrates into lipids in the liver of Sparus aurata. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Huang, X.P.; Guan, J.F.; Chen, Z.M.; Ma, Y.C.; Xie, D.Z.; Ning, L.J.; Li, Y.Y. Effects of dietary leucine and valine levels on growth performance, glycolipid metabolism and immune response in Tilapia GIFT Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 121, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.D.; Liu, Y.; Ren, H.M.; Jin, X.W.; Zhou, X.Q.; Wu, P. Declined flesh quality resulting from niacin deficiency is associated with elevated glycolysis and impaired mitochondrial homeostasis in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandyliari, A.; Mallouchos, A.; Papandroulakis, N.; Golla, J.P.; Lam, T.T.; Sakellari, A.; Karavoltsos, S.; Vasiliou, V.; Kapsokefalou, M. Nutrient composition and fatty acid and protein profiles of selected fish by-products. Foods 2020, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Liu, W.B.; Shi, H.J.; Mi, H.F.; Li, X.F. Benfotiamine ameliorates high-carbohydrate diet-induced hepatic oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in Megalobrama amblycephala. Aquacult. Res. 2021, 52, 3174–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.J.; Xu, C.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, B.K.; Liu, W.B.; Chen, D.H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.Y.; Li, X.F. Resveratrol improves the energy sensing and glycolipid metabolism of blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala fed high-carbohydrate diets by activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1 network. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, L.; Liu, Z.; Chu, X.; Xiong, W.; Liu, W.; Li, X. The effectiveness of four Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) precursors in alleviating the high-glucose-induced damage to hepatocytes in Megalobrama amblycephala: Evidence in NAD+ homeostasis, Sirt1/3 activation, redox defense, inflammatory response, apoptosis, and glucose metabolism. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Wachira, M.N.; Osuga, I.M.; Munguti, J.M.; Ambula, M.K.; Subramanian, S.; Tanga, C.M. Efficiency and improved profitability of insect-based aquafeeds for farming Nile tilapia fish (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Animals 2021, 11, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kwak, K.W.; Park, E.S.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, K.; et al. Evaluation of subchronic oral dose toxicity of freeze-dried skimmed powder of Zophobas atratus larvae (frpfdZAL) in rats. Foods (Basel, Switzerland). 2020, 9, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Broekhoven, S.; Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; van Huis, A.; van Loon, J.J.A. Growth performance and feed conversion efficiency of three edible mealworm species (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) on diets composed of organic by-products. J. Insect Physiol. 2015, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Regenstein, J.M.; Luo, Y. The importance of ATP-related compounds for the freshness and flavor of post-mortem fish and shellfish muscle: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Drolma, D.; Ye, B.; Yang, M. Boosted meat flavor by the metabolomic effects of Nile tilapia dietary inclusion of Zophobas atratus larval meal. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2024, 29, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, D.; Hu, X.; Chen, W.; Zou, C.; Zou, J. Effects of Spirulina platensis as a substitute for fishmeal on the liver of zig-zag eel (Mastacembelus armatus) infected with Aeromonas hydrophila. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics. 2025, 56, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Ji, S.; Liu, T.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, G. Resveratrol reduces senescence-associated secretory phenotype by SIRT1/NF-κB pathway in gut of the annual fish Nothobranchius guentheri. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 80, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Gao, J.; Nie, Z.; Xu, G. Effects of resveratrol on lipid metabolism in liver of red tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 261, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Qiao, M.; Sun, X.; Li, G. Resveratrol alleviates inflammation and ER stress through SIRT1/NRF2 to delay ovarian aging in a short-lived fish. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, B.; Zhao, X.; Tao, S.; Sun, P.; Monroig, Ó.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, M. Evaluation of the optimum dietary arachidonic acid level and its essentiality for black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii): Based on growth and lipid metabolism. Aquac. Nutr. 2024, 2024, 5589032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, L.; Rahman, A.; Govindharajan, S.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Waqas, M. Effects of varying dietary concentrations of menadione nicotinamide bisulphite (VK3) on growth performance, muscle composition, liver and muscle menaquinone-4 concentration, and antioxidant capacities of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) alevins. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L. Integrated analysis of lncRNA and circRNA mediated ceRNA regulatory networks in skin reveals innate immunity differences between wild-type and yellow mutant rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 802731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Lei, J.; Mao, L.H.; Wang, Q.L.; Xu, F.; Ran, T.; et al. NAMPT and NAPRT, key enzymes in NAD salvage synthesis pathway, are of negative prognostic value in colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of NAD-boosting molecules: The in vivo evidence. Cell. Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S. Skin transcriptome profiling of the blass bloched rockfish (Sebastes pachycephalus) with different body color patterns. Korean J. Ichthyol. 2020, 32, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protas, M.E. and N.H. Patel. 2008. Evolution of coloration patterns. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 24, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J.K.; Uy, J.A.; Hauber, M.E.; Hoekstra, H.E.; Safran, R.J. Vertebrate pigmentation: from underlying genes to adaptive function. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamason, R.L.; Mohideen, M.A.P.; Mest, J.R.; Wong, A.C.; Norton, H.L.; Aros, M.C.; Jurynec, M.J.; Mao, X.; Humphreville, V.R.; Humbert, J.E.; et al. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science, 2005, 310, 1782–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Shi, M.; Ma, X.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, C. Metabolomic analysis revealed the inflammatory and oxidative stress regulation in response to Vibrio infection in Plectropomus leopardus. J. Fish Biol. 2024, 105, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeddi, I.; Saiz, L. Computational design of single-stranded DNA hairpin aptamers immobilized on a biosensor substrate. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, M.; Wei, S.; Qin, X.; Qin, Q.; Li, P. Research progress and prospects for the use of aptamers in aquaculture biosecurity. Aquaculture 2021, 534, 736257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Lin, X.; Huang, L.; Yan, Q.; Wang, J.; Weng, Q.; Zhengzhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, J. Transcriptomic analysis of the inhibition mechanisms against Pseudomonas plecoglossicida by antibacterial aptamer B4. Front Vet Sci. 2024, 11, 1511234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Weng, P.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chang, K.; Wang, S.; Lin, G.; Hu, C. IRF9 promotes apoptosis and innate immunity by inhibiting SIRT1-p53 axis in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 103, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMoia, T.E.; Shulman, G.I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin action. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Hou, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhu, H.; Qiao, M.; Sun, X.; Li, G. Metformin protects against inflammation, oxidative stress to delay Poly I:C-Induced aging-like phenomena in the gut of an annual fish. J Gerontol A. Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022, 77, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.W.; Chen, S.N.; Pang, A.N.; Peng, X.Y.; Li, N.; Liu, L.H.; Nie, P. SIRT6 positively regulates antiviral response in a bony fish, the Chinese perch Siniperca chuatsi. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 150, 109662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.Q.; Wu, H.C.; Hu, Y.T.; Lu, Z.J.; Lai, X.L.; Chen, H.P.; He, Z.C.; Luo, X.C.; Li, Y.W.; Dan, X.M. Transcriptomic analysis reveals innate immune mechanisms of an underlying parasite-resistant grouper hybrid (Epinephelus fuscogutatus × Epinephelus lanceolatus). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2021, 119, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahnsteiner, F.; Weismann, T.; Patzner, R.A. Physiological and biochemical parameters for egg quality determination in lake trout, Salmo trutta lacustris. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1999, 20, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahnsteiner, F.; Urbanyi, B.; Horvath, A.; Weismann, T. Bio-markers for egg quality determination in cyprinid fish. Aquaculture 2001, 195, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.B. Influence of nucleoside triphosphates, inorganic salts, NADH, catecholamines, and oxygen saturation on nitrite-induced oxidation of rainbow trout haemoglobin. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 1993, 12, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.B.; Nikinmaa, M.; Weber, R.E. Environmental perturbations of oxygen transport in teleost fishes: Causes, consequences, and compensations. J. Exp. Biol. 1993, 179, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cashon, R.E.; Vayda, M.E.; Sidell, B.D. Kinetic characterization of myoglobins from vertebrates with vastly different body temperatures. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997, 118, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.D.; Snyder, H.E. Nonenzymatic reduction and oxidation of myoglobin and hemoglobin by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides and flavins. J. Biol. Chem. 1969, 244, 6702–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaijan, M.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Faustman, C. Characteristics and gel properties of muscles from sardine (Sardinella gibbosa) and mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) caught in Thailand. Food Chem. 2006, 97, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.P.; Hultin, H.O. Contributions of blood and blood components to lipid oxidation in fish muscle. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7413–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, C.P.; Kjærsgård, I.V.H.; Jessen, F.; Jacobsen, C. Protein and lipid oxidation during frozen storage of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8118–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M. J.; Børresen, T. Effect of freezing on biochemical properties of Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus). J Aquat Food Prod Technol 1995, 4, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shumilina, E.; Ciampa, A.; Capozzi, F.; Rustad, T.; Dikiy, A. NMR approach for monitoring post-mortem changes in Atlantic salmon fillets stored at 0 and 4°C. Food Chemistry, 2015, 184, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).