Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Hydrolysate Preparation

2.2. Treatment of PBMCs with the Digestive Enzyme Hydrolysate of Tuna Meat

2.3. Viability of PBMCs

2.4. Effect of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate on the Level of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) in PBMCs

2.5. Western Blot Assay for Sirtuin 1 and Sirtuin 2 in PBMCs

2.6. ATP Production by PBMCs

2.7. Antioxidant Activity of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate

2.8. Concentrations of NAD+ Precursors, Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotineamide (NAM), in Tuna Red and Dark Meats

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

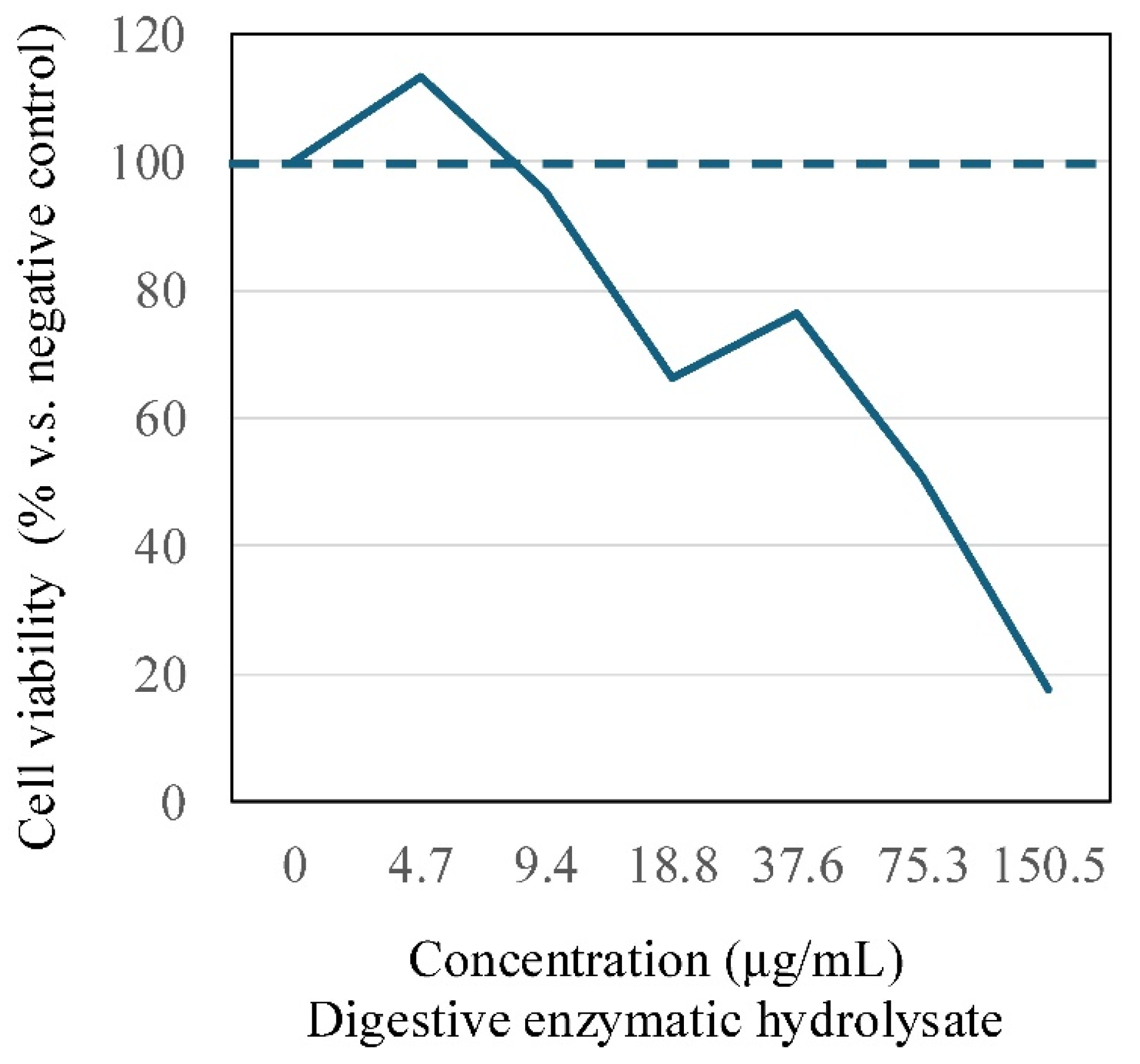

3.1. Cell Viability of PBMCs

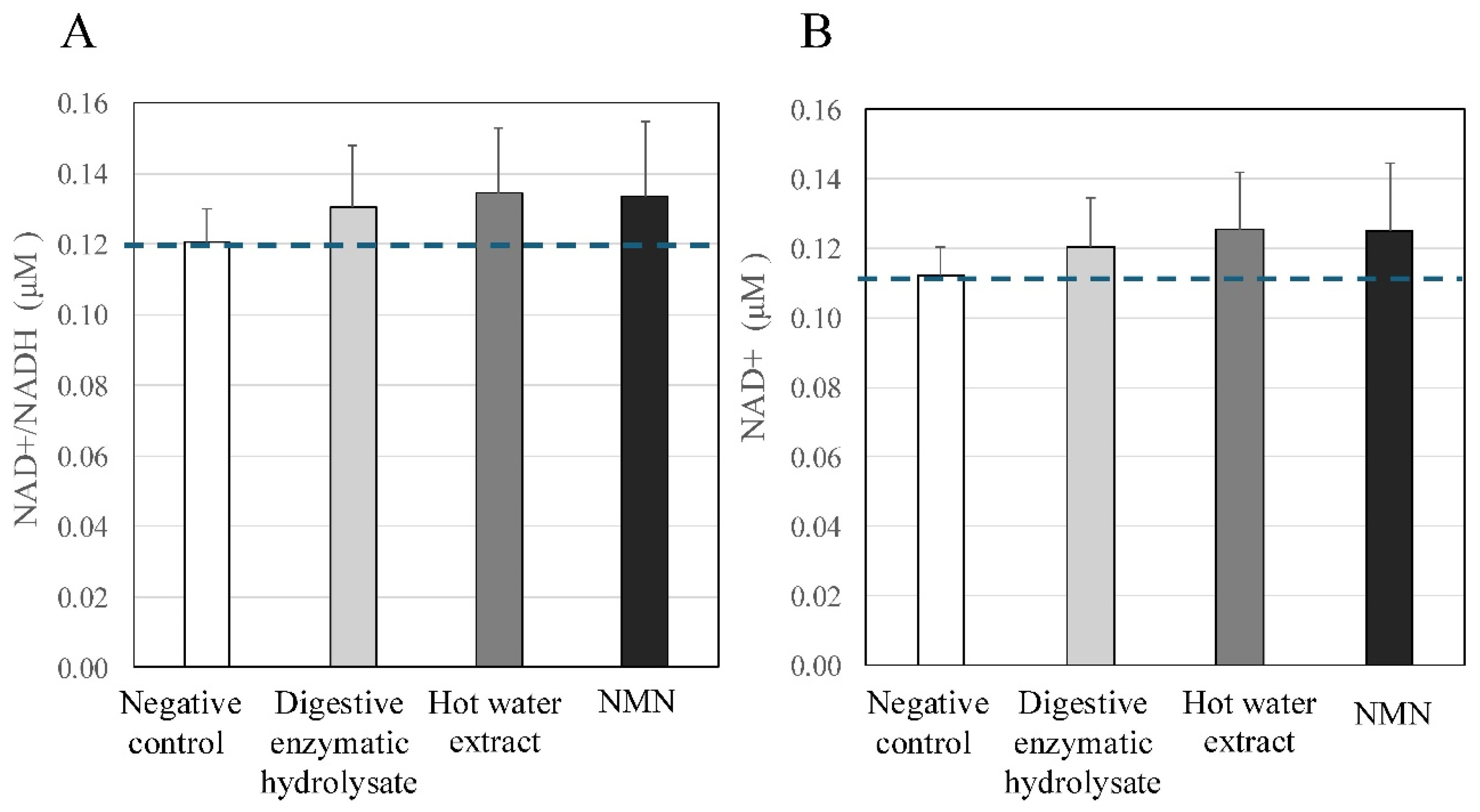

3.2. Effect of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate on the Level of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) in PBMCs

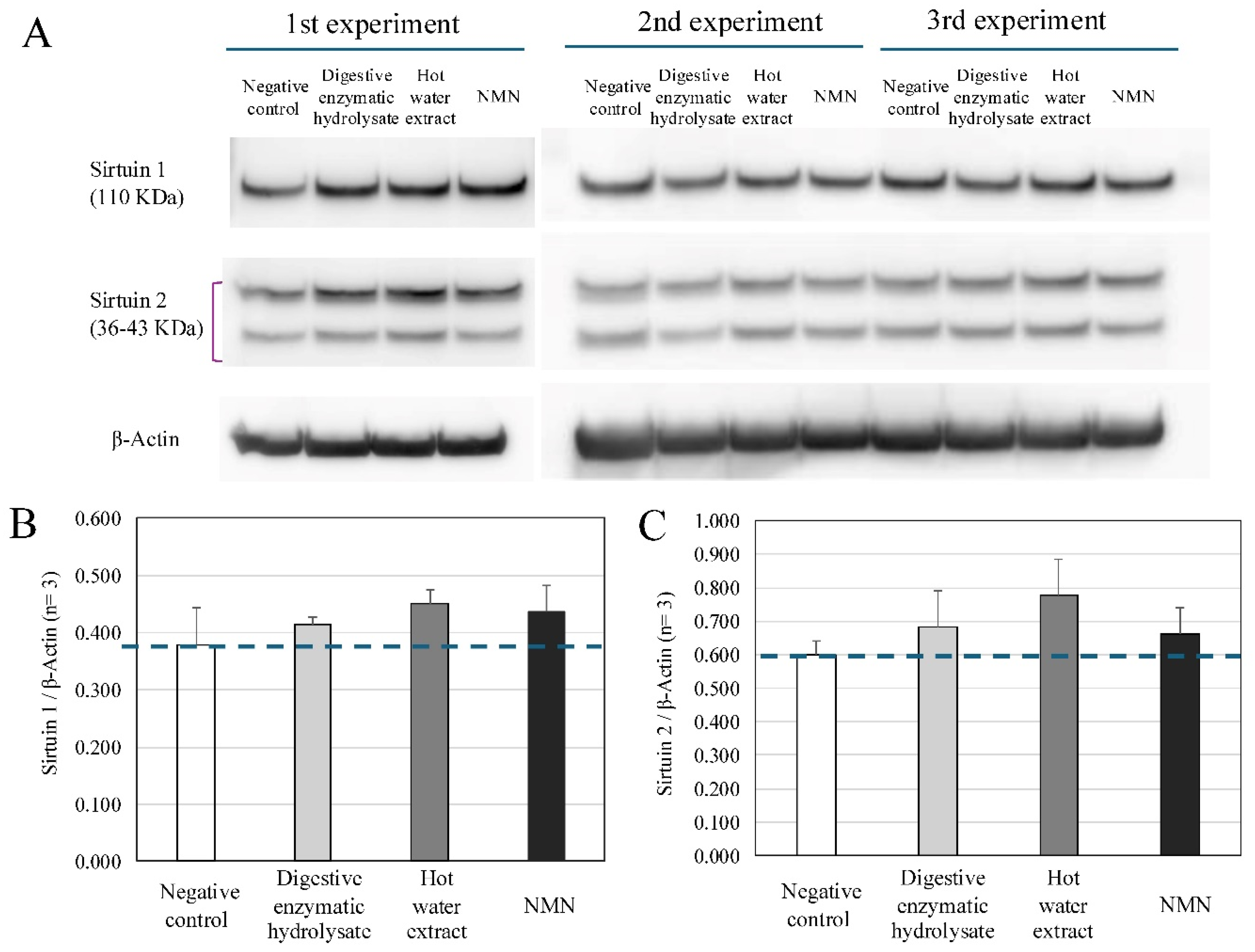

3.3. Effects of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate on the Expression of Sirtuin 1 and Sirtuin 2 in PBMCs

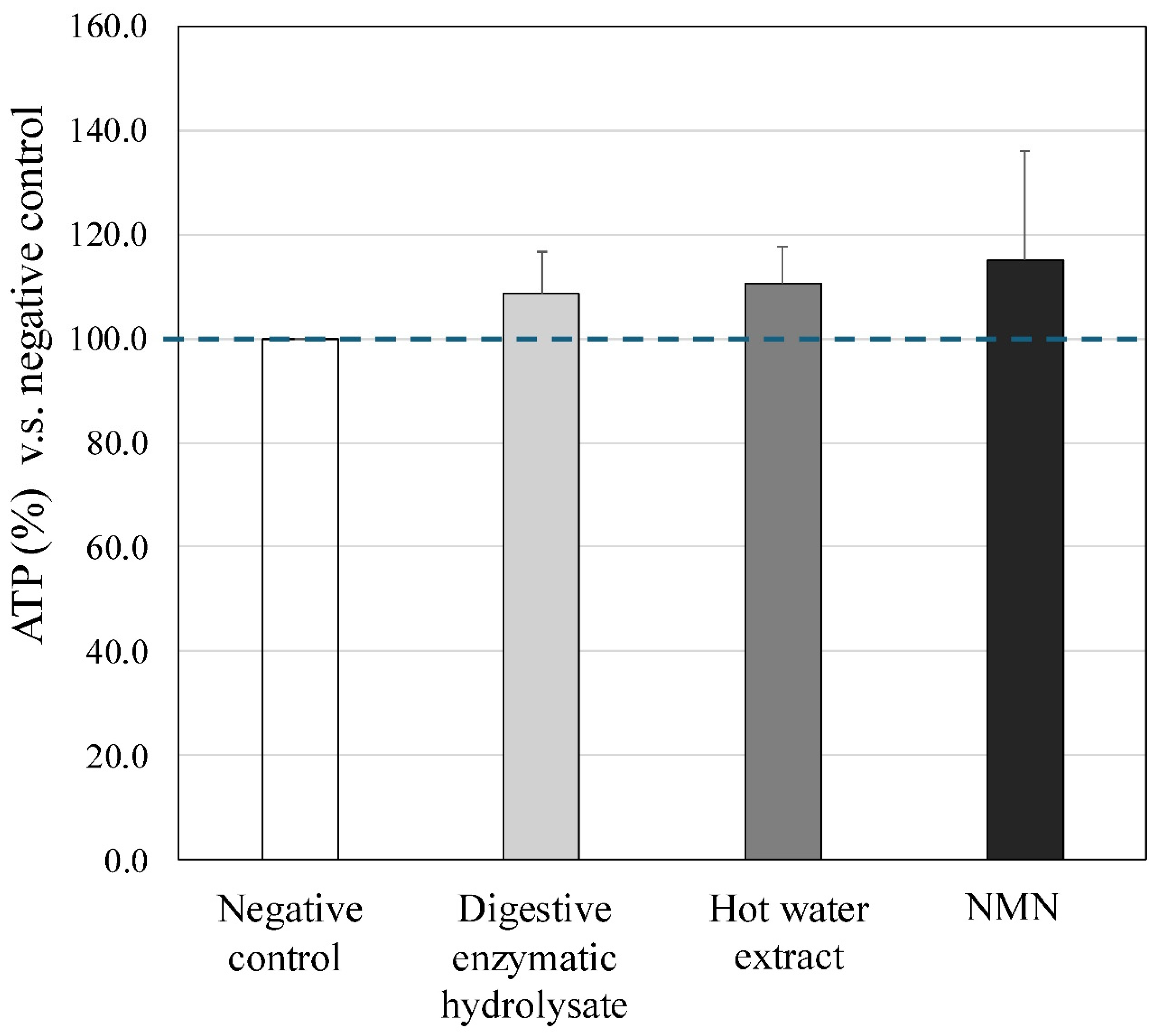

3.4. Effect of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate on ATP Production by PBMCs

3.5. Antioxidative Activity of Digestive Enzyme Tuna Hydrolysate

3.6. Concentrations of NAD+ Precursors, NMN and NAM, in Tuna Red And Dark Meats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ESCAP. Ageing in Asia and the Pacific: Overview; ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017.

- Yan-Feng Zhou, Xing-Yue Song, An Pan, Woon-Puay Koh. Nutrition and Healthy Ageing in Asia: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 15, 3153. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bautmans I, Knoop V, Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan J, Maier AB, Beard JR, Freiberger E, Belsky D, Aubertin-Leheudre M, Mikton C, Cesari M, Sumi Y, Diaz T, Banerjee A; WHO Working Group on Vitality Capacity. WHO working definition of vitality capacity for healthy longevity monitoring. Lancet Healthy Longev. 3(11):e789-e796, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Chen C, Zhou J, Ye L, Li Y, Xu L, Xu Z, Li X, Wei Y, Liu J, Lv Y, Shi X. Healthy lifestyle in late-life, longevity genes, and life expectancy among older adults: a 20-year, population-based, prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4(10):e535-e543, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Molendijk M., Molero P., Ortuno Sanchez-Pedreno, F., Van der Does, W.Angel Martinez-Gonzalez M. Diet quality and depression risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 226, 346–354, 2018.

- Chen L.K., Arai H., Assantachai P., Akishita M., Chew S.T.H., Dumlao L.C., Duque G., Woo J. Roles of nutrition in muscle health of community-dwelling older adults: Evidence-based expert consensus from Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 1653–1672, 2022.

- Zhang J., Zhao A. Dietary Diversity and Healthy Aging: A Prospective Study. Nutrients, 13, 1787, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; Song, X.Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, G.C.; Neelakantan, N.; van Dam, R.M.; Feng, L.; Yuan, J.M.; Pan, A.; Koh, W.P. Association Between Dietary Patterns in Midlife and Healthy Ageing in Chinese Adults: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc., 22, 1279–1286, 2021.

- Zhou, Y.F.; Lai, J.S.; Chong, M.F.; Tong, E.H.; Neelakantan, N.; Pan, A.; Koh, W.P. Association between changes in diet quality from mid-life to late-life and healthy ageing: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Age Ageing, 51, afac232, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aihemaitijiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Ye, C.; Halimulati, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z. Long-Term High Dietary Diversity Maintains Good Physical Function in Chinese Elderly: A Cohort Study Based on CLHLS from 2011 to 2018. Nutrients, 14, 1730, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hata, T.; Seino, S.; Yokoyama, Y.; Narita, M.; Nishi, M.; Hida, A.; Shinkai, S.; Kitamura, A.; Fujiwara, Y. Interaction of Eating Status and Dietary Variety on Incident Functional Disability among Older Japanese Adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging, 26, 698–705, 2022.

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, A.; Wu, W.; Ren, Z.X.; Yang, C.L.; Wang, P.Y.; Zhang, Y.M. Beneficial Effect of Dietary Diversity on the Risk of Disability in Activities of Daily Living in Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients, 12, 3263, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.T.C.; Richards, M.; Chan, W.C.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Lee, R.S.Y.; Lam, L.C.W. Lower risk of incident dementia among Chinese older adults having three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruits a day. Age Ageing, 46, 773–779, 2017.

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Higher fruit and vegetable variety associated with lower risk of cognitive impairment in Chinese community-dwelling older men: A 4-year cohort study. Eur. J. Nutr., 61, 1791–1799, 2022.

- Wang, R.S.; Wang, B.L.; Huang, Y.N.; Wan, T.T.H. The combined effect of physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake on decreasing cognitive decline in older Taiwanese adults. Sci. Rep., 12, 9825, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Fotuhi, P. Mohassel, K. Yaffe. Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease: a complex association. Nat Clin Pract Neurol, 5 (3), 140-152, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Niti, M.; Feng, L.; Yap, K.B.; Ng, T.P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplements and Cognitive Decline: Singapore Longitudinal Aging Studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging, 15, 32–35, 2011.

- Matsuoka, Y.J.; Sawada, N.; Mimura, M.; Shikimoto, R.; Nozaki, S.; Hamazaki, K.; Uchitomi, Y.; Tsugane, S. Dietary fish, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid consumption, and depression risk in Japan: A population-based prospective cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry, 7, e1242, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Yumiko Yamashita, Michiaki Yamashita. Identification of a novel selenium-containing compound, selenoneine, as the predominant chemical form of organic selenium in the blood of bluefin tuna. J Biol Chem, 285(24):18134-8, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Yumiko Yamashita, Takeshi Yabu, Michiaki Yamashita. Discovery of the strong antioxidant selenoneine in tuna and selenium redox metabolism. World J Biol Chem., 1(5):144-50, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Junko Masuda, Chiho Umemura, Miki Yokozawa, Ken Yamauchi, Takuya Seko, Michiaki Yamashita, Yumiko Yamashita. Dietary Supplementation of Selenoneine-Containing Tuna Dark Muscle Extract Effectively Reduces Pathology of Experimental Colorectal Cancers in Mice. Nutrients, 10(10):1380, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Masaaki Miyata, Koki Matsushita, Ryunosuke Shindo, Yutaro Shimokawa, Yoshimasa Sugiura, Michiaki Yamashita. Selenoneine Ameliorates Hepatocellular Injury and Hepatic Steatosis in a Mouse Model of NAFLD. Nutrients, 12(6):1898, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wan X, Garg NJ. Sirtuin Control of Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Chagas Disease Models. Front Cell Infect Microbiol., 11:693051. eCollection 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wan W, Hua F, Fang P, Li C, Deng F, Chen S, Ying J, Wang X. Regulation of Mitophagy by Sirtuin Family Proteins: A Vital Role in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 9;14:845330. 845330. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Chen HH, Yu XF, Lv JL, Liu YY, Liu YS, Zheng G, Zhao JQ, Wei YF, Guo JY, Liu FH, Chang Q, Zhang YX, Liu CG, Zhao YH. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7(1):402, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Imai S, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 24(8):464-71. Epub, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ji Z, Liu GH, Qu J. Mitochondrial sirtuins, metabolism, and aging. J Genet Genomics. 49(4):287-298. Epub, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Pérez R, Wanders RJA, van Karnebeek CDM, Houtkooper RH. NAD(+) homeostasis in human health and disease. EMBO Mol Med. 13(7):e13943. Epub, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chini CCS, Cordeiro HS, Tran NLK, Chini EN. NAD metabolism: Role in senescence regulation and aging. Aging Cell. 23(1):e13920. Epub, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yaku K, Nakagawa T. NAD(+) Precursors in Human Health and Disease: Current Status and Future Prospects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 39(16-18):1133-1149. Epub 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alegre GFS, Pastore GM. NAD+ Precursors Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN) and Nicotinamide Riboside (NR): Potential Dietary Contribution to Health. Curr Nutr Rep. 12(3):445-464. Epub 2023. [CrossRef]

- Loreto A, Antoniou C, Merlini E, Gilley J, Coleman MP. NMN: The NAD precursor at the intersection between axon degeneration and anti-ageing therapies. Neurosci Res. 197:18-24. Epub, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fang EF, Kassahun H, Croteau DL, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Marosi K, Lu H, Shamanna RA, Kalyanasundaram S, Bollineni RC, Wilson MA, Iser WB, Wollman BN, Morevati M, Li J, Kerr JS, Lu Q, Waltz TB, Tian J, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, Nilsen H, Bohr VA. NAD(+) Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell Metab. 24(4):566-581, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wilson N, Kataura T, Korsgen ME, Sun C, Sarkar S, Korolchuk VI. The autophagy-NAD axis in longevity and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 33(9):788-802. Epub, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdulatef Mrghni Ahhmed, Michio Muguruma.A review of meat protein hydrolysates and hypertension. Meat Sci., Sep;86(1):110-118.Epub 2010. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Yang M, Han J, Lu C, Li Y, Su X. Effects of dietary tuna dark muscle enzymatic hydrolysis and cooking drip supplementations on growth performance, antioxidant activity and gut microbiota modulation of Bama mini-piglets. RSC Adv. 9(43):25084-25093. eCollection, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Ovissipour, A. Abedian Kenari, A. Motamedzadegan, R.M. Nazari. Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis of visceral waste proteins of Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares), Food Bioprocess Technol., 5: 696-705, 2021.

- Terauchi K, Kobayashi H, Yatabe K, Yui N, Fujiya H, Niki H, Musha H, Yudoh K. The NAD-Dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1 regulates the expression of osteogenic transcriptional activator runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and production of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 in chondrocytes in osteoarthritis. Int. J Molecular Science, 17(7), 2016. [CrossRef]

- Shu Somemura, Takanori Kuma Kanaka Yatabe, Chizuko Sasaki, Hiroto Fujiya 1, Hisateru Niki, Kazuo Yudoh. Physiologic Mechanical Stress Directly Induces Bone Formation by Activating Glucose Transporter 1 (Glut 1) in Osteoblasts, Inducing Signaling via NAD+-Dependent Deacetylase (Sirtuin 1) and Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2 (Runx2). International J. Molecular Science, 22(16), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Chiang WC. Mitophagy in aging and longevity. IUBMB Life. 74(4):296-316. Epub, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Onishi M, Yamano K, Sato M, Matsuda N, Okamoto K. Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. EMBO J. 40(3):e104705. Epub, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Leduc-Gaudet JP, Hussain SNA, Barreiro E, Gouspillou G. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Mitophagy in Skeletal Muscle Health and Aging. Int J Mol Sci. 22(15):8179, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Bai J, Cui Z, Li Y, Gao Q, Miao Y, Xiong B. Polyamine metabolite spermidine rejuvenates oocyte quality by enhancing mitophagy during female reproductive aging. Nat Aging. 3(11):1372-1386. Epub, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Villarejo-Zori B, Viedma-Poyatos Á, Zapata-Muñoz J, Benítez-Fernández R, Frutos-Lisón MD, Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC, Area-Gómez E, Gomez-Duran A, Boya P. Mitophagy curtails cytosolic mtDNA-dependent activation of cGAS/STING inflammation during aging. Nat Commun. 15(1):830, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mercurio L, Morelli M, Scarponi C, Scaglione GL, Pallotta S, Avitabile D, Albanesi C, Madonna S. Enhanced NAMPT-Mediated NAD Salvage Pathway Contributes to Psoriasis Pathogenesis by Amplifying Epithelial Auto-Inflammatory Circuits. Int J Mol Sci. 22(13):6860, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Xu J, Williams K, Easley M, Elder JB, Lonser R, Lang FF, Lapalombella R, Sampath D, Puduvalli VK. Inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) salvage pathway, to target glioma heterogeneity through mitochondrial oxidative stress. Neuro Oncol. 24(2):229-244, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Tan S, Wang T, Sun R, Li S, Tian P, Li M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Yan Y, Dong Z, Yan L, Yue X, Wu Z, Li C, Yamagata K, Gao L, Ma C, Li T, Liang X. NAD + salvage governs mitochondrial metabolism, invigorating natural killer cell antitumor immunity. Hepatology. 78(2):468-485. Epub, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Su M, Qiu F, Li Y, Che T, Li N, Zhang S. Mechanisms of the NAD(+) salvage pathway in enhancing skeletal muscle function. Front Cell Dev Biol. 12:14648155. eCollection 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seko T, Uchida H, Sato Y, Imamura S, Ishihara K, Yamashita Y, Yamashita M. Selenoneine Is Methylated in the Bodies of Mice and then Excreted in Urine as Se-Methylselenoneine. Biol Trace Elem Res. 202(8):3672-3685. Epub 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita M, Yamashita Y, Ando T, Wakamiya J, Akiba S. Identification and determination of selenoneine, 2-selenyl-Nα, Nα, Nα-trimethyl-L-histidine, as the major organic selenium in blood cells in a fish-eating population on remote Japanese islands. Biol Trace Elem Res 156:36–44, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Rohn I, Kroepfl N, Aschner M, Bornhorst J, Kuehnelt D, Schwerdtle T. Selenoneine ameliorates peroxide-induced oxidative stress in C. elegans. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 55:78-81. Epub, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tohfuku T, Ando H, Morishita N, Yamashita M, Kondo M. Dietary Intake of Selenoneine Enhances Antioxidant Activity in the Muscles of the Amberjack Seriola dumerili Grown in Aquaculture. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 23(6):847-853. Epub 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Karakhanova S, Hartwig W, D’Haese JG, Philippov PP, Werner J, Bazhin AV. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial ROS in Cancer: Novel Targets for Anticancer Therapy. J Cell Physiol. 231(12):2570-81. Epub, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Angelova PR, Abramov AY. Role of mitochondrial ROS in the brain: from physiology to neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 592(5):692-702. Epub, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Annesley SJ, Fisher PR. Mitochondria in Health and Disease. Cells. 5;8(7):680, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).