1. Introduction

Atmospheric emission inventories provide relevant information of the amount or rates of contribution of air pollutants and greenhouse gases (GHGs), produced by different sources over a specific region, for past, present, or future time [

1,

2]. Atmospheric emission inventories have been used both for policy and research purposes. Emission inventories provide the temporal behavior during the time, to track the reaching of goals in term of reductions of emissions [e.g, 3,4]. . On the other hand, emissions inventories provide the input for chemical transport models, which simulate the behavior of pollutants in the atmosphere for both current and hypothetical emission scenarios, as well as for atmospheric forecasting [

5,

6,

7]. Emission data is probably the most important input for chemical transport models [

8].

The building and use of accurate atmospheric emission inventories are directly related to some of the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) as the SGD 3 (Good Health and Well Being), to identify the main air pollution sources and guide air quality regulations; SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), to support city-level policies for cleaner transport, energy, and waste management; and SGD 13 (Climate Action), about GHGs and other pollutants involved in the energetic balance of the atmosphere, to quantify their emissions sources and sinks, to track mitigation progress [

9].

International initiatives aim to develop and make the results of emission inventories available to inform scientists and policymakers. The Edgar Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research is a dataset that covers time-series emission inventories for anthropogenic sources of primary pollutants and GHGs, for all countries worldwide, with a spatial resolution of up to 0.1° (approximately 11.1 km) [

10]. The Edgar Emissions Database is one of the most used global atmospheric emission inventories. The CAMS emission inventory contains gridded distributions of global anthropogenic and natural emissions of atmospheric pollutants and GHGs, with resolution up to 0.1° [

11].

Although emission inventories have been developed for years, they still can have high uncertainty levels [

12,

13,

14]. Apart from the uncertainties inherent in emission models as simplifications of real emissions, other factors, such as the limitations of statistical data and the lack of local emission factors, can also significantly contribute. Uncertainty is also influenced by the method to downscale total emission results to a grid-cell level, accompanied by high-time resolution disaggregation, for use in a chemical transport model [

15]. The assessment of uncertainty is required to clarify the usefulness and identify the sources that deserve dedicated future improvements in emission inventories [

16].

The quality of an emission inventory has typically been defined by the quality of the statistical data, the emission factors, and the models used in its development. Additionally, when available, comparisons with other emission inventories have been used. Another approach to assessing the quality of an emission inventory is the use of it as input for atmospheric modeling. For this purpose, Mathias et al. (2017) [

8] highlighted the need to work with accurate emissions data and provided an outlook for improving the spatial and temporal distribution of emissions inventories for use in chemical transport models. Park et al. (2023)[

14] assessed emission inventories for sulfur dioxide (SO2) and oxides of nitrogen (NOx) from large point sources in South Korea, evaluating the modeling performance through a comparison of computed and recorded data for these pollutants. Malasani et al. (2024)[

17] assessed five global emission inventory datasets to provide the spatial and temporal distribution of mercury over India, and also evaluated the modeling performance by comparing modeled and measured concentrations of this pollutant.

Online coupled meteorology–atmospheric chemistry models, which consider the influence and feedback between atmospheric and air quality variables, have undergone significant evolution in recent years in atmospheric modeling [

18]. For this purpose, the online approach provides consistent treatment of physical and chemical processes for both numerical weather and air quality modeling, allowing the analysis through a “one atmosphere” approach. If the meteorological component is properly modeled and the comparison of the modeled air pollution levels to the corresponding records indicates consistency. In that case, we can deduce that the emission inventory is reliable and provides, although with uncertainties, useful information.

For Cuenca, a city located in the Andean region of southern Ecuador, several emission inventories have been developed since 2007. The results of the 2014 emission inventory [

19] were used to conduct several modeling experiments to assess the influence of parameters and options coded in the Weather Research and Forecasting with Chemistry (WRF-Chem 3.2) model. These numerical experiments employed the online option to propose a configuration of parameters for modeling both meteorological and air quality variables, employing the “one atmosphere” approach [

20,

21] in urban areas of the Equatorial Andean region.

The last emission inventory for this city was created using 2021 as the base year [

22], which is referred to hereafter as EI 2021. Although its uncertainty was assessed, the purpose of this contribution is to evaluate the quality and usefulness of EI 2021 by incorporating its results as input to WRF-Chem for modeling as “one atmosphere”, both meteorological and air quality variables. Additionally, the EI 2021 EI results are compared with the corresponding results from the Edgar Emissions Dataset.

1.1. Location and the Air Quality Network of Cuenca

Cuenca is located in the Andean region of southern Ecuador (

Figure 1), characterized by a complex topography and diverse land-use configuration. The urban area is located at 2550 masl; however, the Andes Mountains, to the west of the city, have heights exceeding 4000 masl (

Figure 1c). Its air quality network has been operational since 2008, in accordance with national regulations. Currently, the air quality network is operated by the EMOV EP (Spanish acronym for Empresa Pública Municipal de Movilidad, Tránsito y Transporte de Cuenca). In the historic center of the city, an automatic station (MUN,

Figure 1d) measures real-time meteorological variables (temperature, wind speed, global solar radiation, and rainfall) and air quality variables (nitrogen dioxide, NO

2; fine particulate matter, PM

2.5; and ozone, O

3). Additionally, the air quality network comprises approximately twenty passive stations, distributed throughout the city, for recording mean monthly levels of NO

2 and O

3.

Between 2012 and 2024, the MUN station measured PM

2.5 yearly mean concentrations that ranged between 5.7 and 14.5 µg m

−3 [

23], more significant than the current World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation (5.0 µg m

−3) [

24]. Moreover, during 98 days in 2024, the 24-h mean PM

2.5 levels exceeded the current WHO guideline (15 µg m

−3). During 6 days in 2024, the O

3 levels exceeded the WHO guideline (100 µg m

−3, maximum daily mean over 8 consecutive hours). Air quality and meteorological records from the MUN station are relevant for assessing the performance of atmospheric models in Cuenca.

Additionally, for this contribution, we collected meteorological data from two meteorological stations (SAY and SOL) located west of the urban area (

Figure 1c), which are operated by ETAPA EP (Spanish acronym for Empresa Pública Municipal de Telecomunicaciones, Agua Potable, Alcantarillado y Saneamiento), the entity in charge of the water management in Cuenca.

Table 1 summarizes the availability of meteorological parameters for this study.

1.2. The Emission Inventory of the Year 2021 (EI 2021)

The last atmospheric emission inventory for Cuenca was compiled for the year 2021, at the initiative of the EMOV EP [

25], in accordance with the recommended practice of accounting for primary pollutants and GHGs [

13]. Nitrogen oxides (NO

x), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOC), sulphur dioxide (SO

2), particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 µm or less (PM

10), and particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 µm or less (PM

2.5), were included as primary pollutants. In addition, carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), and nitrous oxide (N

2O) were included as GHGs.

Sources included on-road traffic, vegetation, industries, use of solvents, service stations, domestic combustion of liquid petroleum gas (LPG), use of solvents, air traffic, landfills, artisanal production of bricks, dust resuspension, and mining activities, under the territory of the Cantón Cuenca (

Figure 1c).

Figure 2 depicts the location of industries, service stations, landfills, and kilns used for the artisanal production of bricks.

The EI 2021 was developed to estimate real emissions in the best way possible in the territory of Cuenca, with the main goals of providing a proper emission inventory that can serve as a reference for air pollution management and the development of a future atmospheric forecasting system.

On-road traffic is a relevant source of emissions in Cuenca. It was estimated that about 150 800 vehicles were driven in Cuenca during 2021. Most of them (89.9%) use gasoline, while the rest (approximately 10.1%) use diesel. The presence of hybrid and electric cars was marginal. The composition of the vehicle park, in terms of percentages of used fuel, vehicle type, engine size, and year of manufacture, was deduced from statistical data of 2021 from the RTV (Spanish acronym for Revisión Técnica Vehicular), a technical control for exhaust emissions and mechanical conditions of vehicles, which has been applied in Cuenca since 2008. A survey and review of the literature were conducted to estimate the annual distances traveled and the efficiency (distance traveled per unit of fuel) by vehicle type, respectively. For consistency, the estimated fuel consumption was matched to the official statistical data on gasoline and diesel sales at Cuenca service stations for 2021. Hot, cold, and evaporative emissions were included [

26], and the total results were spatially disaggregated on the emissions grid, using the intensity of the traffic map generated by EMOV EP as a proxy variable.

Vegetation is an important source of VOC. Apart from the type of vegetation and foliar biomass, the surface temperature and photosynthetically active radiation are the main physical drivers of VOC emissions from this source. For this purpose, meteorological data for 2021 were modeled for the emissions grid using the WRF model. Applying the basic model proposed by Guenther et al. [

27,

28], the emissions of isoprene, monoterpenes, and other volatile organic compounds were estimated.

Combustion emissions from industries were estimated using official data on fuel consumption and emission factors from the literature.

LPG is the main fuel used in the city for domestic cooking. Similarly, the combustion emissions were estimated using official data on LPG consumption and emission factors from the literature. Total yearly emissions were spatially distributed on the grid, based on a map of population density.

The emissions of VOC from service stations were estimated using official information on the sale of fuels (gasoline and diesel) in 2021. Emissions of VOC due to the use of solvents were estimated using a per-capita emission factor and the map of population density.

Emissions from landfills were estimated using the first-order decay model proposed by the IPCC [

29], accounting for the amount of municipal solid waste stored at each facility, the composition of the solid waste, and the landfill's technical performance.

The yearly emissions of the primary pollutants were spatially distributed over a grid of 8000 cells (the third subdomain of the model,

Figure 1c), each measuring 1 km on a side. For this purpose, the bottom-up approach was prioritized to estimate and locate the cells of emissions, complemented by the top-down approach for sources for which data are lacking and the bottom-up approach cannot be used.

More information on the emissions models for the considered sources can be found in the corresponding technical report, which shows the results of the 2021 emission inventory of Cuenca [

25].

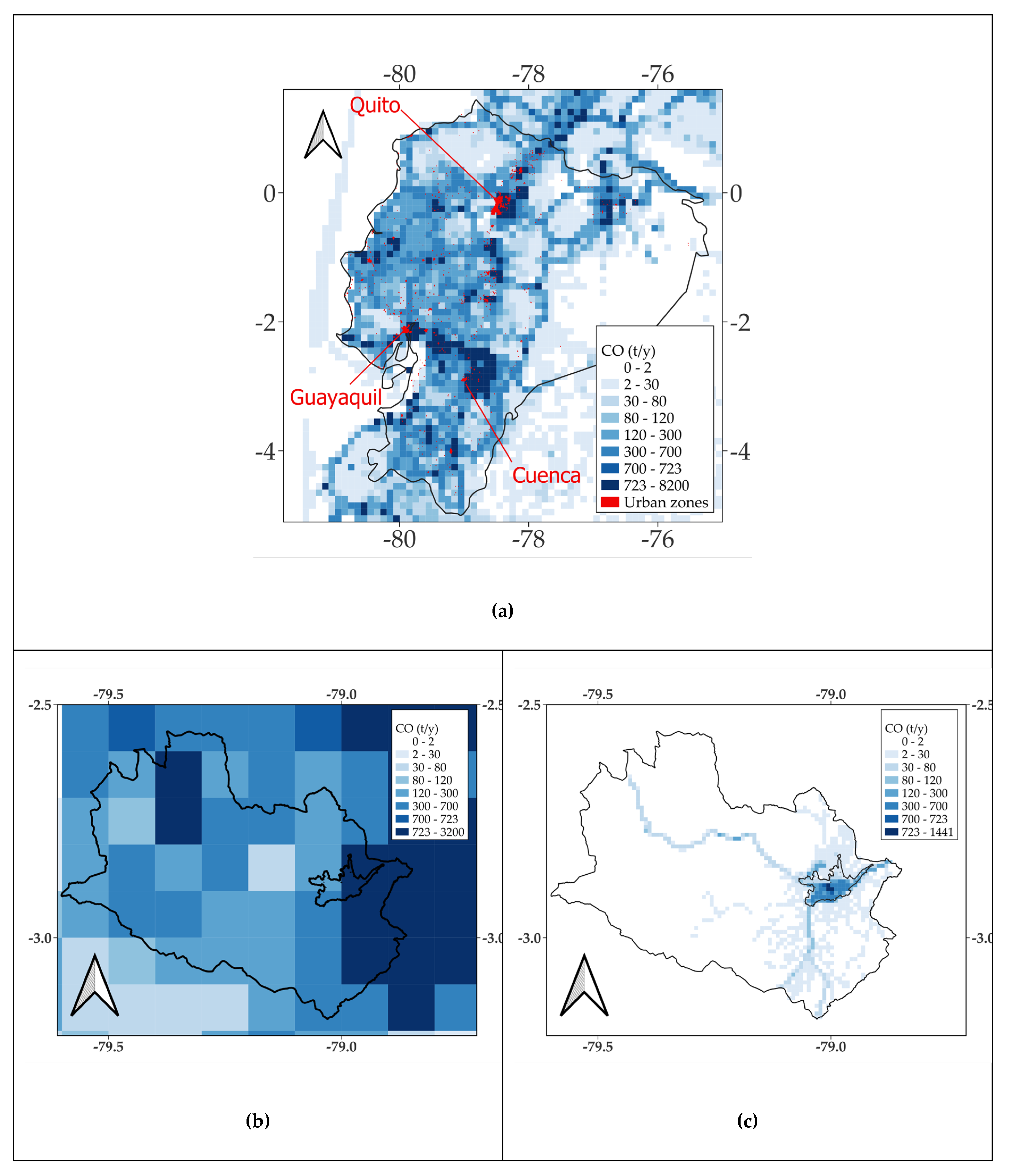

On-road traffic was the main source of NO

x (89.8%), CO (95.1%), PM

10 (73.3%), and PM

2.5 (65%) (

Table 2). Industries were the most important source of SO

2 (98.0%). The use of solvents (36.0%), on-road traffic (31.8%), and vegetation (21.3%) were the main sources of VOC. After on-road traffic, artisanal bricks contributed significantly to PM

10 (19.3%) and PM

2.5 (27.2%) emissions. On-road traffic (66.3%), industries (20.1%), and the combustion of domestic LPG (13.0%) were the main sources of CO

2 (

Table 3).

Figure 2 depicts the spatial distribution of the yearly emissions of CO, NO

x, VOC, and PM

2.5.

A qualitative approach was employed to assess the uncertainty of EI 2021, using a five-category scale, ranging from A (high quality) to E (poor quality), to evaluate the quality of activity data and emission factors. Emissions by sector were classified into categories C, D, and E. The lowest grades were attributed to the quality of the emission factors [

25].

Figure 3.

Spatial Distribution of the EI 2021 emissions (t y-1): (a) CO, (b) NOx, (c) VOC, (d) PM2.5. .

Figure 3.

Spatial Distribution of the EI 2021 emissions (t y-1): (a) CO, (b) NOx, (c) VOC, (d) PM2.5. .

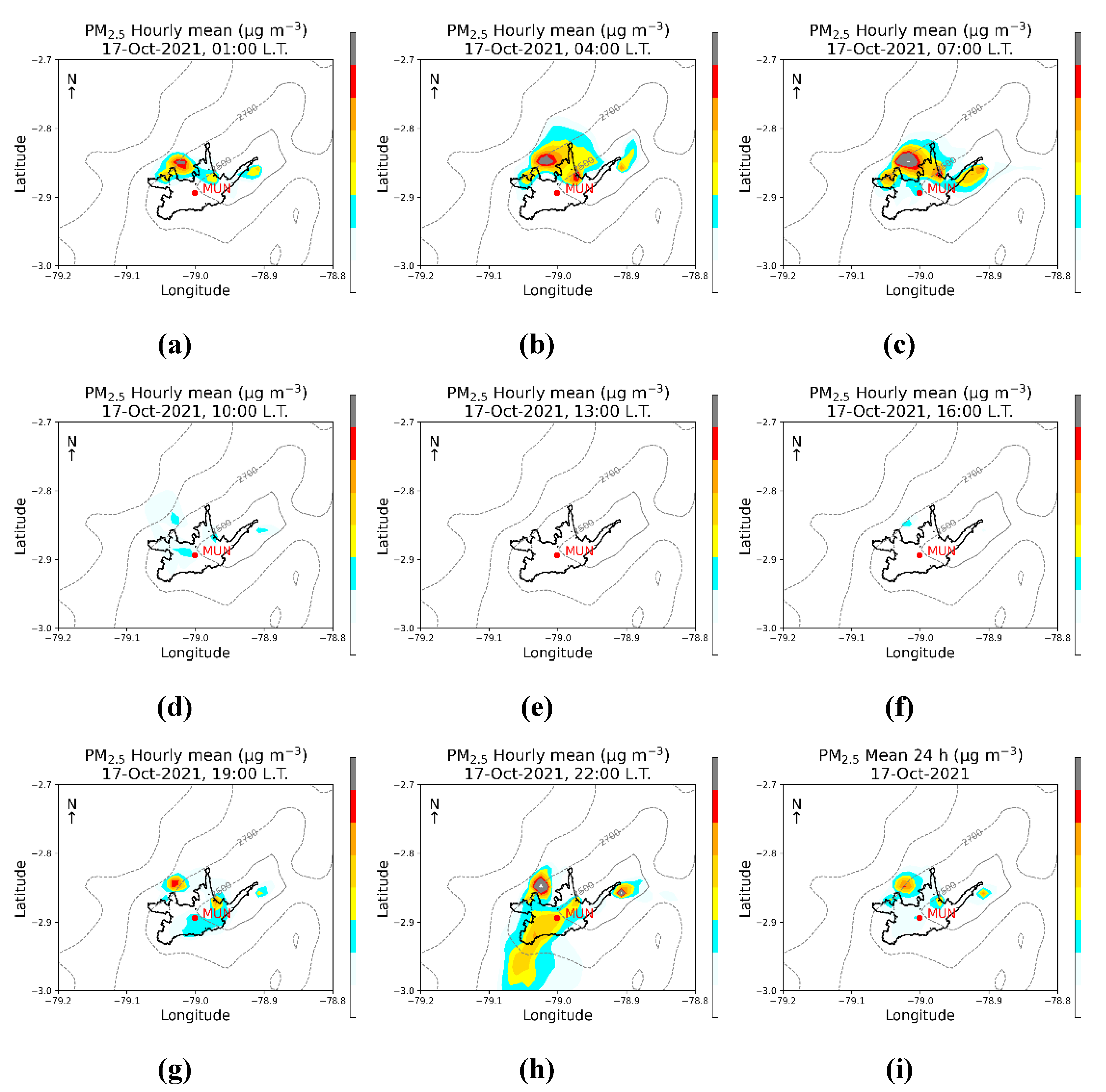

4. Discussion and Conclusions

We assessed the quality of the EI 2021 emission inventory from Cuenca by using it as input to the WRF-Chem model to simulate atmospheric and air quality variables at a high spatial resolution (1 km). To our knowledge, this is the first time that an atmospheric emission inventory from the Equatorial Andean region has been formally assessed by atmospheric modeling of meteorological (surface temperature, surface wind speed, and total daily rainfall) and air pollution variables (maximum 1 h NO

2 mean per day, mean 24 h PM

2.5, maximum 8 h O

3 mean per day, monthly mean levels of NO

2 and O

3). We utilized a state-of-the-art tool that models the direct effects of aerosols on meteorological variables. The results indicated that both meteorological and air quality variables were acceptably modeled, suggesting the quality of the EI 2021 emission inventory and WRF-Chem's ability to model the atmosphere as a unique system [

13,

47].

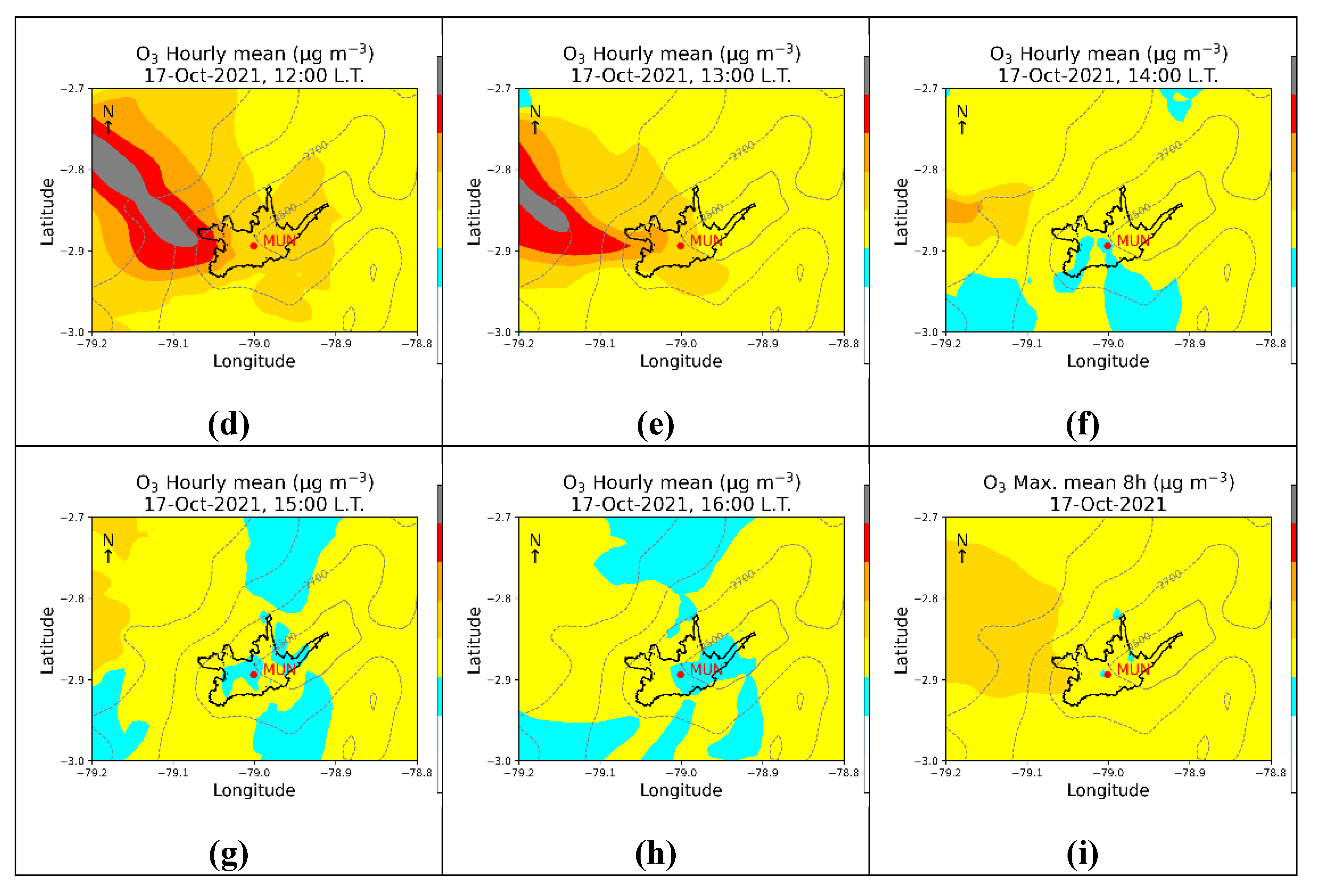

The comparison of the EI 2021 results with the corresponding emissions from the Edgar Dataset indicated a good agreement for NOx. In both cases, transportation and industry were identified as the main sources of NOx.

The CO emissions from the EI 2021 were 1.7 times higher than those from the Edgar Dataset, despite the latter including other sectors, such as agricultural activities. We hypothesize that the difference can be partly explained by Cuenca's geographical altitude (2550 masl). Molina and Molina reported that, at 2240 masl, the Mexico City Metropolitan Area has 23% less oxygen (O

2) than at sea level [

2]. Similarly, at the height of Cuenca, the lower O

2 availability affects combustion processes, leading to higher atmospheric emission factors of primary pollutants [

48,

49].

The VOC emission from EI 2021 was 2.7 times higher than the estimate from the Edgar Dataset. Although there is significant uncertainty in VOC emissions, the main reason for the difference could be that the Edgar Dataset covers human-made sources, whereas the EI 2021 also includes VOC emissions from vegetation.

The SO2 emission by the EI 2021 was about 29% of the Edgar estimation. In both cases, industry and transportation were identified as the primary sources of SO2. As the EMOP EV conducted a dedicated sampling campaign in service stations to characterize the sulfur content of the fuels delivered in Cuenca during 2021, we considered the EI 2021 estimate to be more reliable.

The PM10 and PM2.5 emissions from EI 2021 were 75% and 66% of the estimates from the Edgar Dataset, respectively. These ratios seem consistent, as the EI 2021 did not include emissions from agricultural activities.

The comparison of the EI 2021 results with the corresponding emissions from the Edgar Dataset indicated a good agreement for CO2. Important differences were identified for CH4 and N2O. The primary purpose of the EI 2021 was, in addition to VOCs from vegetation, to focus on combustion and fugitive emissions from human-made sources. Therefore, the EI 2021 did not include CH4 sources from enteric fermentation, agricultural or livestock activities, nor N2O sources from fertilizer use, both of which were included in the Edgar Dataset, in agreement with the IPCC method.

High levels of uncertainty still characterized the emission inventories [

13]. For the case of the EI 2021, we identified different components that deserve dedicated improvements in the future. In addition to the quality required for the activity data, defining its own emission factors is a priority for the Equatorial Andean region, considering the influence of the decrease in oxygen in the atmosphere with increasing height above sea level, which in turn increases the magnitude of primary pollutant emissions such as CO, VOC, and particulate matter. For countries like Ecuador, in general, there are very few own emission factors, and currently, most of them are taken from the international literature, which is established mostly for locations at sea or at low heights above sea level.

The EI 2021, although with uncertainties, is a valuable contribution in terms of describing the most important sources of primary pollutants and GHGs in Cuenca. The corresponding results can be used as a reference to explore options to improve the air quality, as the change of the composition of the vehicle park, the promotion of electric vehicles, the benefits in terms of the improvement of the fuels’ quality, or the expected health benefits due to the use of exhaust filter particles in diesel vehicles. Additionally, the EI 2021 serves as a proper reference for environmental impact assessments of policies, programs, and projects that affect air quality. Even, the EI 2021 results could be used to explore the modeling performance of a preliminary atmospheric forecasting system.

In the future, to reduce the uncertainty of emission inventories in Cuenca, we identified the following activities:

For on-road traffic, as one of the most important sources of both primary pollutants and GHGs, it is essential to improve and keep updated a map of daily traffic intensities for avenues, roads, and main streets. If possible, collect data to describe the characterization of the type and number of vehicles on the avenues and roads with the highest levels of traffic. For this purpose, traffic counting supported by cameras should be implemented. Another option could be the access and analysis of data describing the dynamic behavior of passengers’ cell phones as a proxy variable to infer the distribution of daily and hourly on-road traffic behavior.

The RTV (Spanish acronym for Revisión Técnica Vehicular) is a technical control for exhaust emissions and mechanical conditions of vehicles, which has been applied in Cuenca since 2008. According to national regulations, it is a prerequisite for the legal use of each vehicle throughout the year. Currently, the RTV controls the hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide exhaust emissions for gasoline vehicles, as well as opacity, a measurement of how much light is blocked by particulate matter, for diesel vehicles.

The database generated by the RTV control is a valuable resource, which was used to characterize the composition of the city's vehicle park. This dataset can include the record of the distance traveled per vehicle each time it is tested annually. This information will enable a more accurate estimation of the distance traveled per year, thereby improving the accuracy of the on-road activity data.

Additionally, it is necessary for each type of vehicle to maintain and update the information on the distance traveled per unit of consumed fuel. For this purpose, apart from the information provided by the vehicle makers, it is advisable to conduct dedicated surveys of vehicle owners who can provide consistent information on the conditions in Cuenca.

Due to both short-term and long-term exceedances of the WHO guidelines [

23], determining local PM2.5 emission factors is a priority, particularly for diesel vehicles and fixed sources that use fossil fuels and biomass. The RTV should additionally include the control of the exhaust emissions of PM

2.5 and NO

x for diesel cars. In fact, the RTV database of the exhaust emission measurements (e.g., [

50,

51,

52]) should be used to deduce local emission factors as a complement to the results from in-route use of on-board measurement devices (e.g., [

53,

54,

55]). Particularly, the viability of deducing PM

2.5 emission factors from opacity records deserves dedicated research, as the literature reports correlated or weak correlations (e.g., [

56,

57]).

Also, it is necessary to define local emissions factors for the NOx and VOC, as precursors of O3. Particularly, it is necessary to characterize local VOC emission factors from gasoline vehicles, vegetation, service stations, and the use of solvents.

Regarding VOC emissions from vegetation, practically no national or local emission factors are available. Additionally, some native species lack information on their VOC emission capacity. Therefore, determining their emission factors [

58,

59] is a priority field of research. Particularly, vegetation is a source with high emission uncertainty. In the future, it will be necessary to have an improved characterization of the spatial configuration of species and of the foliar biomass, as well as its dynamics throughout the annual cycle.

For future emission inventories, as a good practice, other components can be added, such as the quantification of black and elemental carbon [

24].

In general, the availability of atmospheric records is low in the Andean Region of Ecuador [

60,

61]. Particularly, the promotion of vertical sounding of meteorological and air quality species will enhance the characterization of parameters, such as the planetary boundary layer height and the vertical abundance of species, thereby providing useful information for improving the generation of the boundary conditions for modeling purposes and allowing a more complete assessment of the modeling performance by the inclusion of vertical comparisons.

The EI 2021 provided a useful spatial distribution of emissions (resolution of 1 km), as can be inferred from the modeling performance. Apart from the differences in emissions for some primary pollutants, the comparison with the emissions from the Edgar Dataset indicated that the latter is still too coarse (resolution of 11.1 km) for modeling purposes at the required scale for Equatorial Andean cities, such as Cuenca.

One of the advantages of the Edgar Dataset is its consistent use of the same method, although this approach may overlook country-specific details that could enhance the emission estimates and their spatial distribution [

8]. The Edgar Dataset, one of the most widely used emission resources. Georgiou et al. (2022)[

7] reported the performance of an atmospheric forecasting system applied over the Eastern Mediterranean, based on the emission from the Edgar Dataset and the WRF-Chem, assessing the modeling performance of both meteorological and air quality parameters. Yarragunta et al. (2025) [

62] utilized the Edgar Dataset as input to WRF-Chem for atmospheric modeling, similarly assessing the performance of meteorological and air quality quantities. However, our results and comparison to the EI 2021 suggest that for the Equatorial Andean region, the Edgar Dataset results require improvement, at least for some primary pollutants (CO, VOC, SO2) in terms of their magnitude and of the emission spatial configuration of all the pollutants, before they can be used for atmospheric modeling. Their results can be used to generate emissions, possibly using proxy variables, with a high spatial resolution (1 km), which allows for adequate emissions for atmospheric modeling in cities located in the equatorial zone of the Andes.

To assess the quality of the EI 2021, we used version 3.2 of the WRF-Chem model, as had been previously tested in Cuenca to define a recommended configuration of options, which was used in the present contribution. However, there are modeled results for both meteorological and air quality variables that can be improved. For example, the model overestimated global solar radiation, which in part explains the overestimation of O3 levels during the afternoon. New versions and configurations of the WRF-Chem model can be tested to identify a scheme, if any, that improves the modeling of cumulus processes, thereby enhancing the representation of cloud coverage, rainfall, and surface solar radiation. Similarly, the potential benefits from the activation for indirect effects between aerosols and meteorological variables need to be assessed.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of Ecuador. (b, c) Location of the Cantón Cuenca and meteorological stations (white dots). (c) The black rectangle indicates the border of the third subdomain for modeling, a grid composed of 100 columns and 80 rows. (d) Urban area of Cuenca (red border) and the stations of the air quality network (red dots). MUN is an automatic station for both meteorological and air quality variables. The remaining red dots indicate the locations of passive stations.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of Ecuador. (b, c) Location of the Cantón Cuenca and meteorological stations (white dots). (c) The black rectangle indicates the border of the third subdomain for modeling, a grid composed of 100 columns and 80 rows. (d) Urban area of Cuenca (red border) and the stations of the air quality network (red dots). MUN is an automatic station for both meteorological and air quality variables. The remaining red dots indicate the locations of passive stations.

Figure 2.

Location of selected types of emission sources.

Figure 2.

Location of selected types of emission sources.

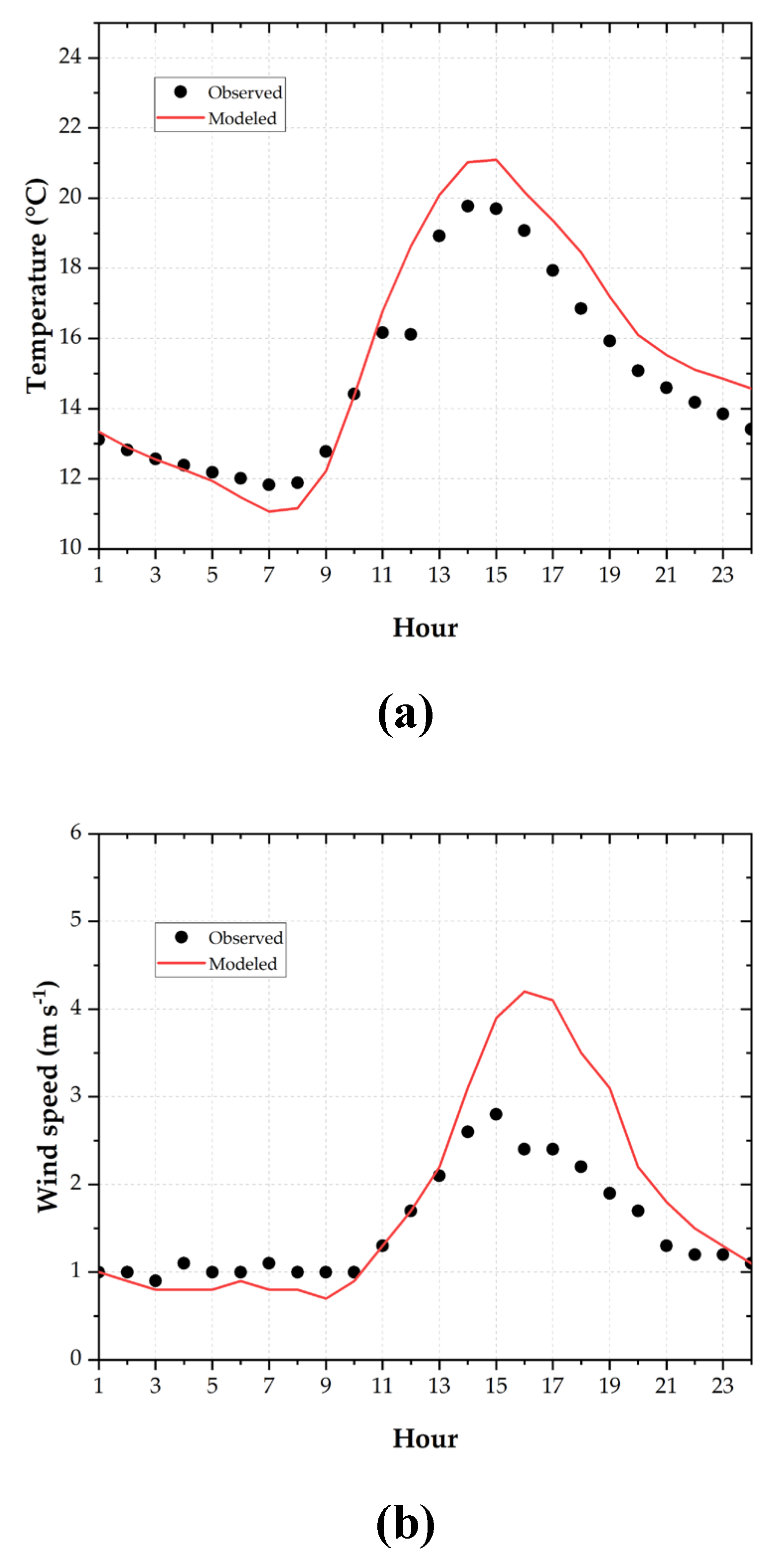

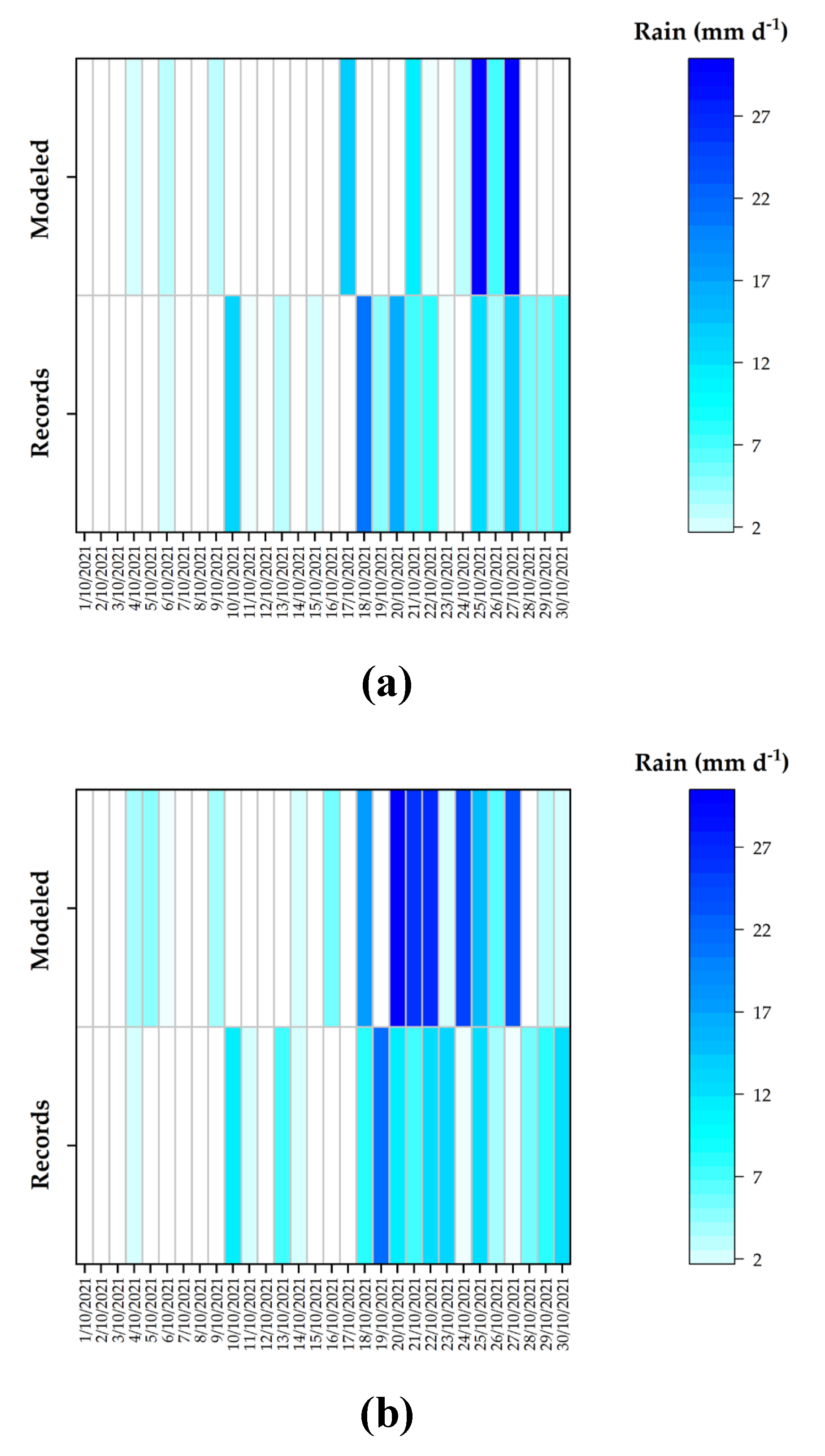

Figure 4.

MUN station. Daily mean profiles during October 2021: (a) Surface temperature. (b) Wind speed. (c) Global solar radiation.

Figure 4.

MUN station. Daily mean profiles during October 2021: (a) Surface temperature. (b) Wind speed. (c) Global solar radiation.

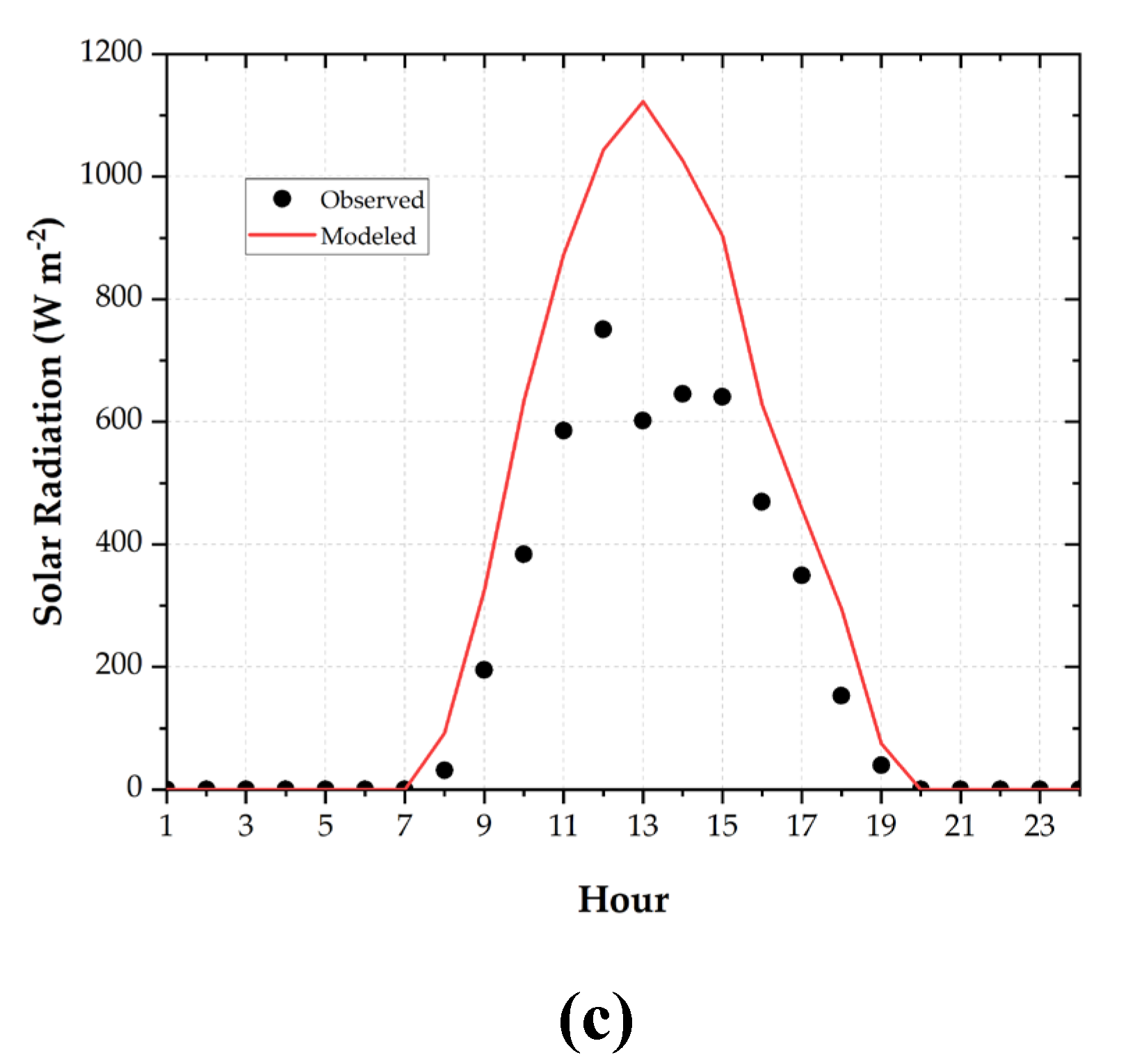

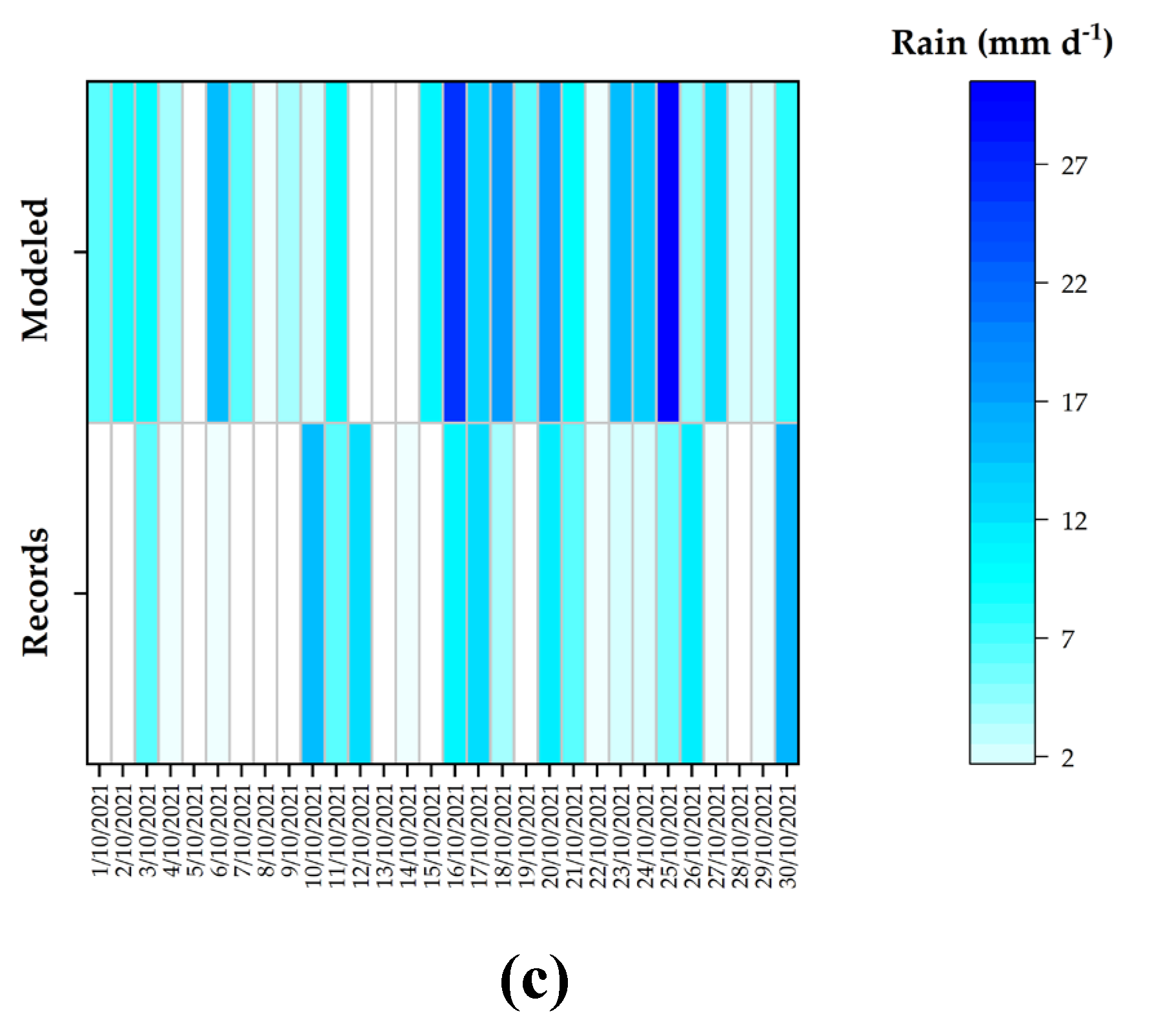

Figure 5.

Rainfall records and modeled values: (a) MUN. (b) SAY. (c) SOL.

Figure 5.

Rainfall records and modeled values: (a) MUN. (b) SAY. (c) SOL.

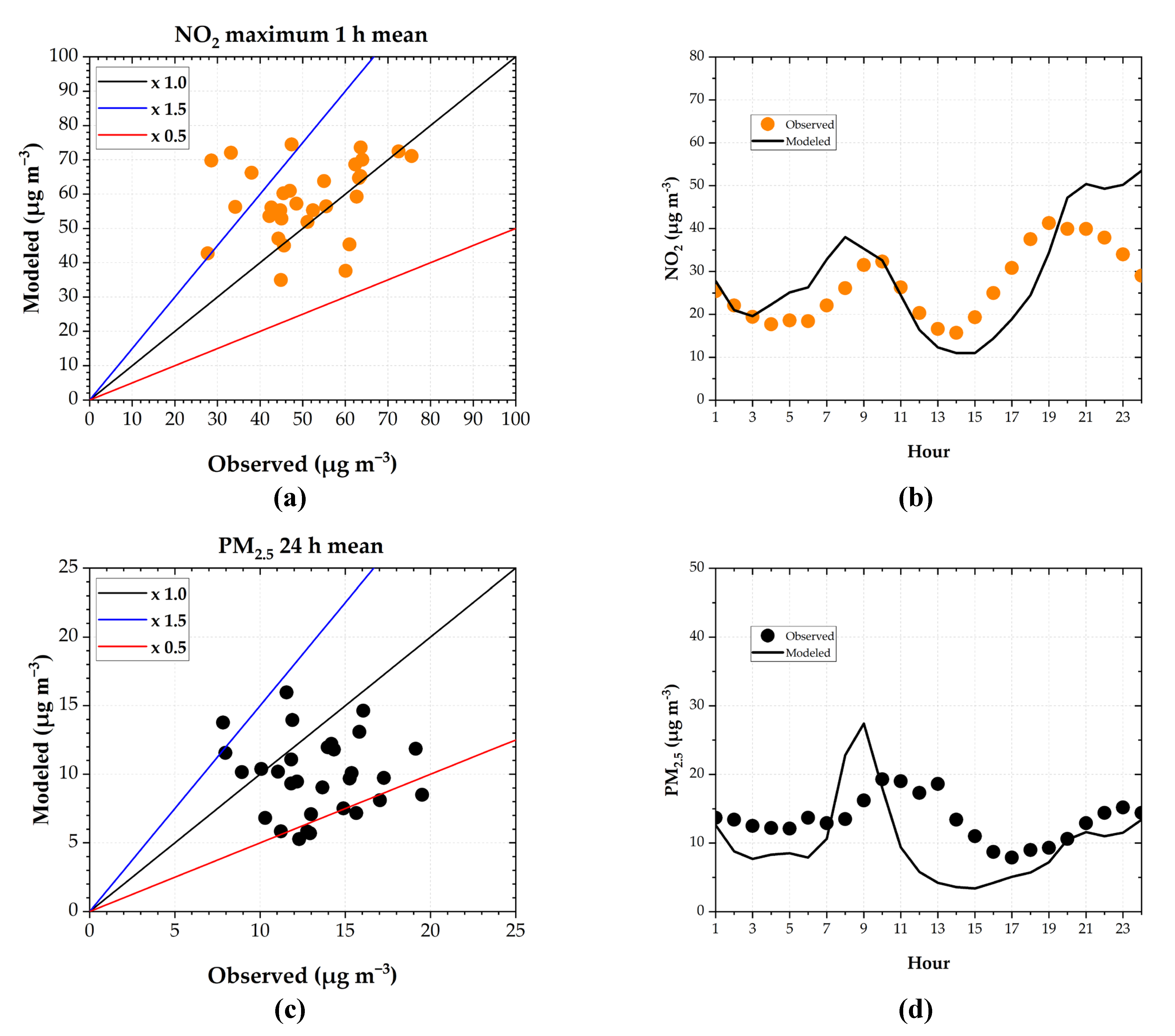

Figure 6.

Observed versus modeled daily concentrations: (a) NO2 1 h maximum; (b) Mean daily profiles of hourly NO2; (c) PM2.5 24 h mean; (d) Mean daily profiles of hourly PM2.5; (e) O3 8 h maximum; (f) Mean daily profiles of hourly O3.

Figure 6.

Observed versus modeled daily concentrations: (a) NO2 1 h maximum; (b) Mean daily profiles of hourly NO2; (c) PM2.5 24 h mean; (d) Mean daily profiles of hourly PM2.5; (e) O3 8 h maximum; (f) Mean daily profiles of hourly O3.

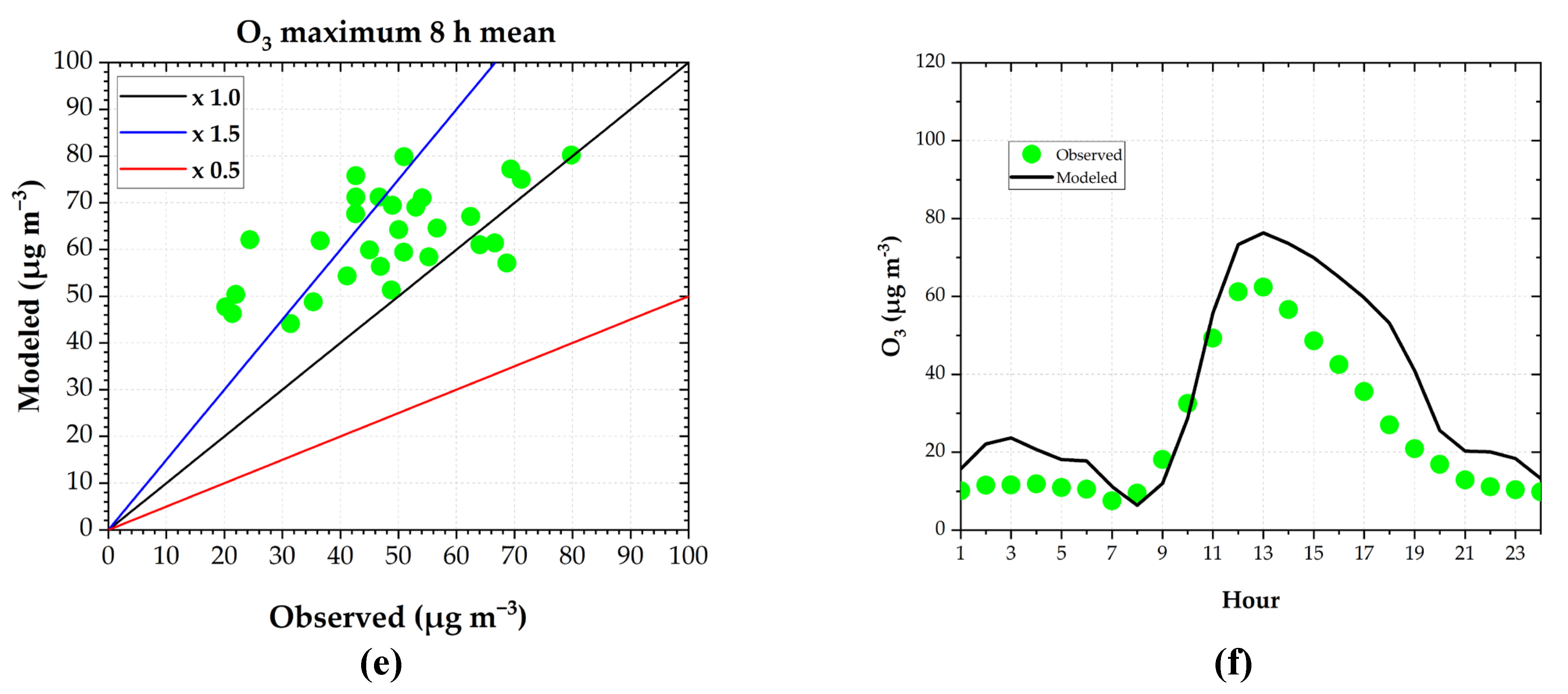

Figure 7.

Observed versus modeled levels at passive stations: (a) NO2 and (b) O3.

Figure 7.

Observed versus modeled levels at passive stations: (a) NO2 and (b) O3.

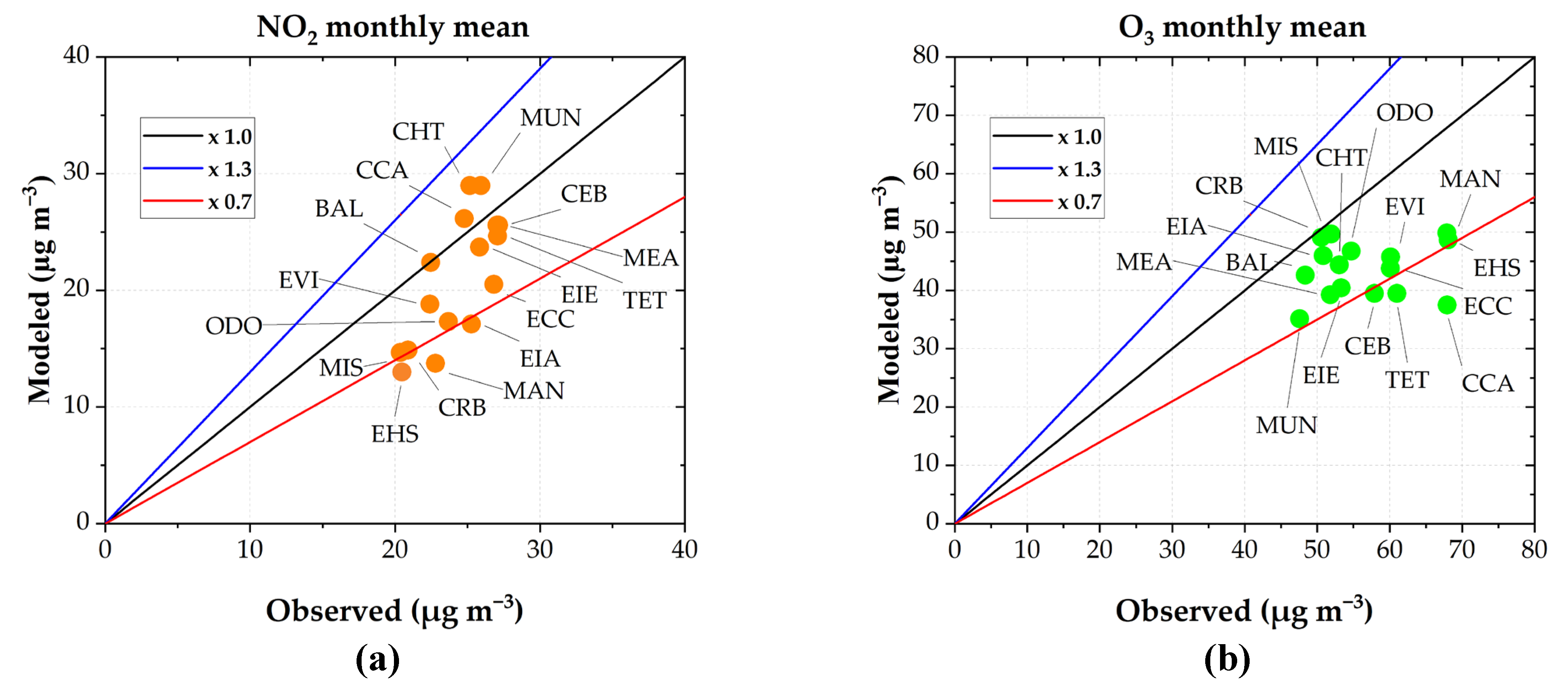

Figure 8.

Modeled PM2.5 levels for 17 Oct 2021. Results in local time (L.T.). Hourly mean concentrations: (a) 01:00, (b) 04:00, (c) 07:00, (d) 10:00, (e) 13:00, (f) 16:00, (g) 19:00, (h) 22:00. (i) Mean concentration during 24 h.

Figure 8.

Modeled PM2.5 levels for 17 Oct 2021. Results in local time (L.T.). Hourly mean concentrations: (a) 01:00, (b) 04:00, (c) 07:00, (d) 10:00, (e) 13:00, (f) 16:00, (g) 19:00, (h) 22:00. (i) Mean concentration during 24 h.

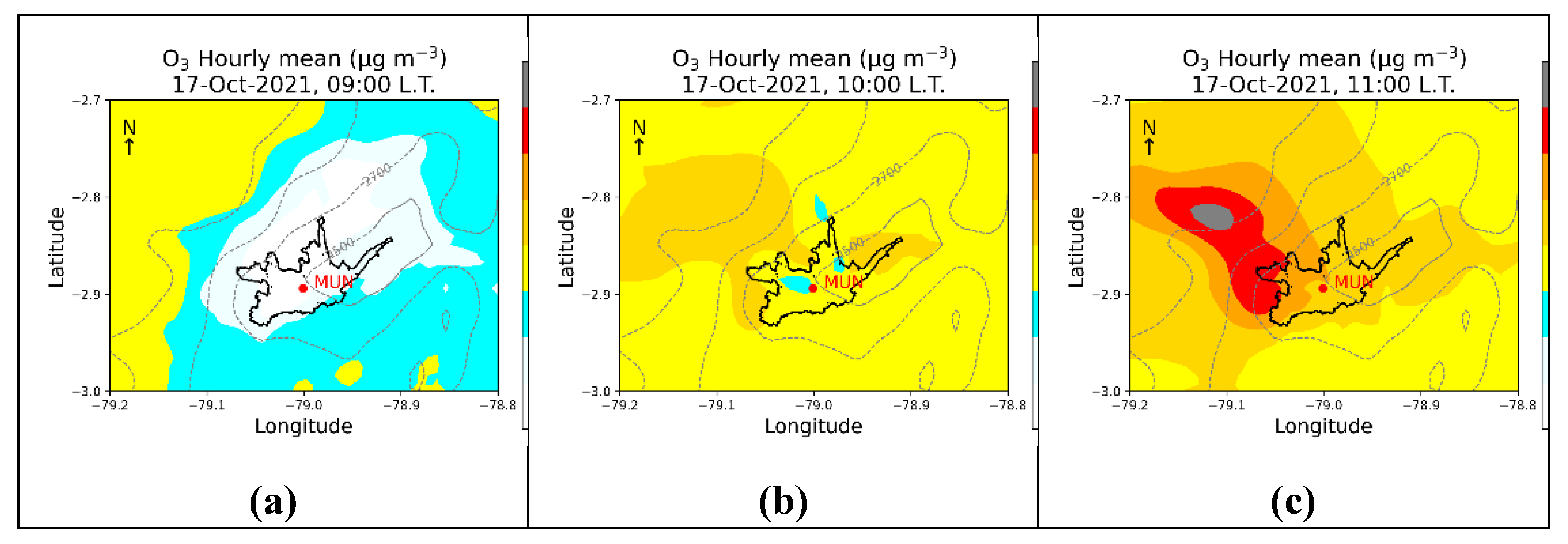

Figure 9.

Modeled O3 levels for 17 Oct 2021. Results in local time (L.T.). Hourly mean concentrations: (a) 09:00, (b) 10:00, (c) 11:00, (d) 12:00, (e) 13:00, (f) 14:00, (g) 15:00, (h) 16:00. (i) Maximum mean concentration during 8 h.

Figure 9.

Modeled O3 levels for 17 Oct 2021. Results in local time (L.T.). Hourly mean concentrations: (a) 09:00, (b) 10:00, (c) 11:00, (d) 12:00, (e) 13:00, (f) 14:00, (g) 15:00, (h) 16:00. (i) Maximum mean concentration during 8 h.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of the CO emission for the year 2021: (a) Ecuador, Edgar dataset (spatial resolution: 11.1 km). (b) Cuenca, Edgar dataset (spatial resolution 11.1 km). (c) Cuenca, EI 2021 (spatial resolution: 1 km).

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of the CO emission for the year 2021: (a) Ecuador, Edgar dataset (spatial resolution: 11.1 km). (b) Cuenca, Edgar dataset (spatial resolution 11.1 km). (c) Cuenca, EI 2021 (spatial resolution: 1 km).

Table 1.

Meteorological stations and availability of records.

Table 1.

Meteorological stations and availability of records.

| Station |

Nomenclature |

Entity |

masl |

Parameters |

| Municipio |

MUN |

EMOV EP |

2582 |

Temperature, wind speed, global solar radiation, and rainfall |

| Sayausí |

SAY |

ETAPA EP |

2622 |

Temperature, global solar radiation, and rainfall |

| Soldados |

SOL |

ETAPA EP |

3466 |

Global solar radiation and rainfall |

Table 2.

Emission Inventory of Cuenca. Primary Pollutants. Year 2021.

Table 2.

Emission Inventory of Cuenca. Primary Pollutants. Year 2021.

| Source |

NOx |

CO |

VOC |

SO2 |

PM10 |

PM2.5 |

| t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

| On-road traffic |

6782.4 |

89.8 |

37 624.3 |

95.1 |

4201.2 |

31.8 |

16.8 |

1.5 |

860.1 |

73.3 |

534.3 |

65.0 |

| Vegetation |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

2813.7 |

21.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Industries |

555.5 |

7.4 |

286.3 |

0.7 |

176.5 |

1.3 |

1095.4 |

98.0 |

71.9 |

6.1 |

52.5 |

6.4 |

| Use of solvents |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4752.4 |

36.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Service stations |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

889.2 |

6.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Domestic LPG |

162.2 |

2.1 |

25.3 |

0.1 |

5.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

10.7 |

0.9 |

10.7 |

1.3 |

| Air Traffic |

15.2 |

0.2 |

31.1 |

0.1 |

4.5 |

0.0 |

3.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

| Landfills |

6.3 |

0.1 |

2.6 |

0.0 |

29.5 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

| Artisanal bricks |

32.6 |

0.4 |

1577.9 |

4.0 |

341.9 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

0.2 |

226.2 |

19.3 |

223.5 |

27.2 |

| Dust resuspension |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Mining |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.4 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Total |

7554 |

100 |

39 547 |

100 |

13 214 |

100 |

1118 |

100 |

1174 |

100 |

822 |

100 |

Table 3.

Emission Inventory of Cuenca. Greenhouse gases. Year 2021.

Table 3.

Emission Inventory of Cuenca. Greenhouse gases. Year 2021.

| Source |

CO2 |

CH4 |

N2O |

| t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

t y-1

|

% |

| On-road traffic |

756 655.4 |

66.3 |

203.8 |

4.1 |

83.1 |

83.3 |

| Industries |

229 111.8 |

20.1 |

4.3 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

| Domestic LPG |

148 890.4 |

13.0 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

10.2 |

10.2 |

| Air Traffic |

4737.2 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

| Landfills |

2621.3 |

0.2 |

4786.6 |

95.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Artisanal bricks |

53 363.7 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

| Total |

1 142 016 |

100 |

4997 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Table 4.

Schemes and options for modeling [

20,

21].

Table 4.

Schemes and options for modeling [

20,

21].

| Component |

WRF variable |

Option |

Model and References |

| Cumulus Parameterization |

cu_physics |

0 |

0 No Cumulus |

| Microphysics |

mp_physics |

3 |

WRF Single–moment 3–class [34] |

| Longwave Radiation |

ra_lw_physics |

1 |

RRTM [35] |

| Shortwave Radiation |

ra_sw_physics |

2 |

Goddard [36] |

| Surface Layer |

sf_sfclay_physics |

1 |

MM5 similarity [37] |

| Planetary Boundary Layer |

bl_pbl_physics |

1 |

Yonsei University [38] |

| Land Surface |

sf_surface_physics |

2 |

Noah [reference] [39] |

| Urban surface |

sf_urban_physics |

0 |

No urban physics |

| Chemical mechanism and aerosol modules |

chem_opt |

7 |

CBMZ and MOSAIC [32,33] |

Table 5.

Metrics for modeling atmospheric variables [

40,

44].

Table 5.

Metrics for modeling atmospheric variables [

40,

44].

| Variable |

Metric |

Benchmark or

Ideal Range |

Accuracy |

| Hourly surface temperature |

GE |

<2 °C |

±2 °C |

| MB |

(-0.5 °C, 0.5 °C) |

| IOA |

≥0.8 |

| Hourly wind speed (10 mas) |

RMSE |

<2 m s−1

|

±1 m s−1

|

| MB |

(-0.5 m s−1, 0.5 m s-1) |

| IOA |

≥0.6 |

| Daily air quality: Max. 1-h NO2, 24-h PM2.5 mean, max. 8-h O3 mean |

MB |

0 |

±50% |

| RMSE |

0 |

| FB |

0 |

| MNB |

0 |

| r |

1 |

| Monthly air quality: NO2 and O3

|

|

|

±30% |

Table 6.

Metrics for modeling meteorological variables.

Table 6.

Metrics for modeling meteorological variables.

| Metric |

MUN |

SAY |

Benchmark |

| Hourly surface temperature: |

| GE |

1.46 |

2.11 |

<2 °C |

| MB |

0.61 |

0.74 |

(-0.5 °C, 0.5 °C) |

| IOA |

0.84 |

0.86 |

≥0.8 |

| Hourly wind speed: |

| RMSE |

1.04 |

NA |

<2 m s−1 |

| MB |

0.31 |

NA |

(-0.5 m s-1, 0.5 m s-1) |

| IOA |

0.72 |

NA |

≥0.6 |

Table 7.

Percentage of records captured by modeling meteorological variables.

Table 7.

Percentage of records captured by modeling meteorological variables.

| Parameter |

MUN |

SAY |

SOL |

| Hourly surface temperature |

78.4 |

60.3 |

NA |

| Hourly wind speed |

75.8 |

NA |

NA |

| Daily rainfall |

46.7 |

80.0 |

73.3 |

Table 8.

Short-term air quality metrics.

Table 8.

Short-term air quality metrics.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Ideal Value |

| Maximum 1 h NO2 mean: |

| MB |

|

|

7.9 |

|

|

0 |

| RMSE |

|

|

15.9 |

|

|

0 |

| FB |

|

|

14.6 |

|

|

0 |

| MNB |

|

|

22.1 |

|

|

0 |

| r |

|

|

0.3 |

|

|

1 |

| 24 h PM2.5 mean: |

| MB |

|

|

-3.40 |

|

|

0 |

| RMSE |

|

|

5.33 |

|

|

0 |

| FB |

|

|

-29.2 |

|

|

0 |

| MNB |

|

|

-21.00 |

|

|

0 |

| r |

|

|

-0.12 |

|

|

1 |

| Maximum 8 h O3 mean: |

| MB |

|

|

14.39 |

|

|

0 |

| RMSE |

|

|

18.74 |

|

|

0 |

| FB |

|

|

25.9 |

|

|

0 |

| MNB |

|

|

41.48 |

|

|

0 |

| r |

|

|

0.61 |

|

|

1 |

Table 9.

Percentage of records captured by modeling air quality variables.

Table 9.

Percentage of records captured by modeling air quality variables.

Short-term air quality: |

| Max. 1 h NO2 mean |

|

|

80.0 |

|

|

|

| 24 h PM2.5 mean |

|

|

76.7 |

|

|

|

| Max. 8 h O3 mean |

|

|

66.7 |

|

|

|

| Average: |

|

|

74.5 |

|

|

|

Long-term air quality: |

| NO2, monthly mean |

|

|

81.3 |

|

|

|

| O3, monthly mean |

|

|

76.5 |

|

|

|

| Average: |

|

|

78.9 |

|

|

|

Table 10.

Comparison to the results from the Edgar Emissions Dataset. Year 2021.

Table 10.

Comparison to the results from the Edgar Emissions Dataset. Year 2021.

| |

EI 2021 (a) |

Edgar Dataset (b) |

Ratio a/b |

| Primary pollutants |

(t y-1) |

(t y-1) |

|

| NOx

|

7554 |

6690 |

1.13 |

| CO |

39 547 |

22 986 |

1.72 |

| VOC |

13 214 |

4970 |

2.66 |

| SO2

|

1118 |

3851 |

0.29 |

| PM10

|

1174 |

1558 |

0.75 |

| PM2.5

|

822 |

1237 |

0.66 |

| GHGs |

(t y-1) |

(t y-1) |

|

| CO2

|

1 142 016 |

1 004 333 |

1.14 |

| CH4

|

4997 |

108 15 |

0.46 |

| N2O |

100 |

392 |

0.26 |

| Total GHGs |

(t CO2 eq. y-1) |

(t CO2 eq. y-1) |

|

| CO2 eq. |

1 304 235 |

1 403 332 |

0.93 |

| GHGs emission per capita: |

(t CO2 eq. per capita y-1) |

(t CO2 eq. per capita y-1) |

|

| CO2 eq. per capita |

2.01 |

2.16 |

0.93 |