Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

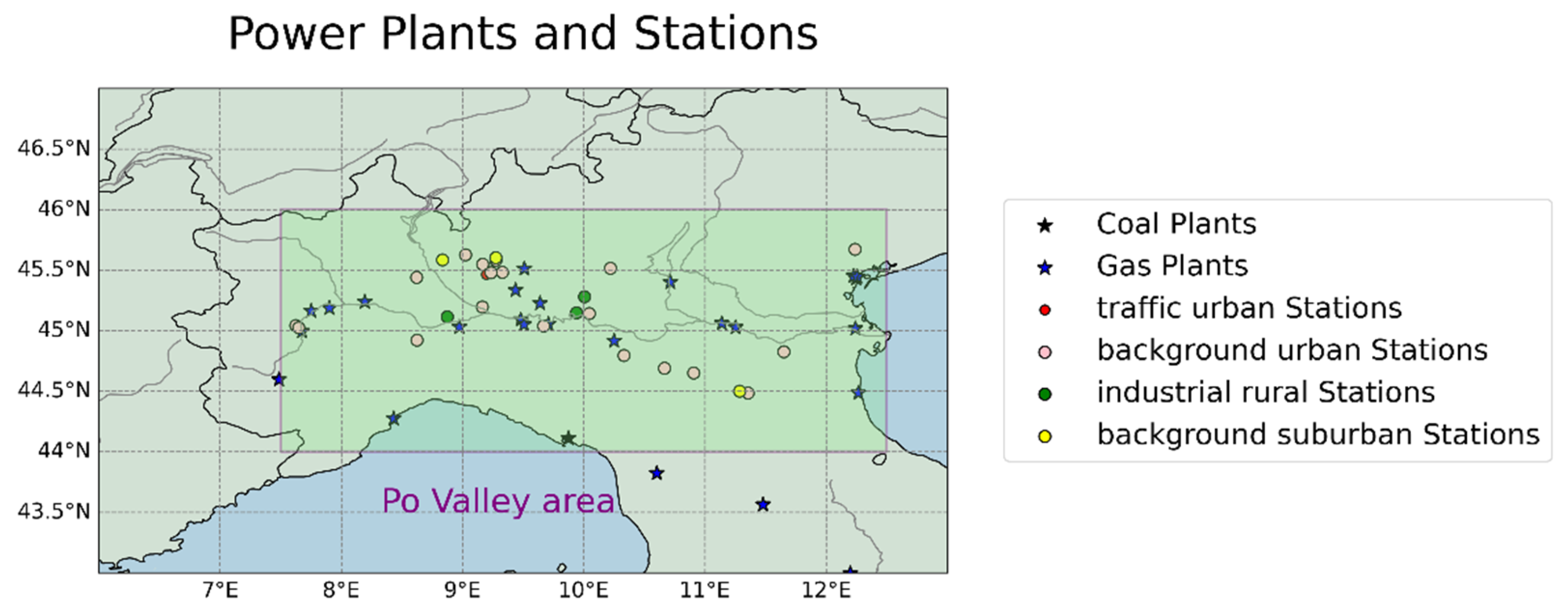

2.1. Area of the Po Valley

2.2. European Environment Agency Air Quality Monitoring

2.3. LOTOS-EUROS Chemical Transport Modelling System

2.5. Methodology

3. Results

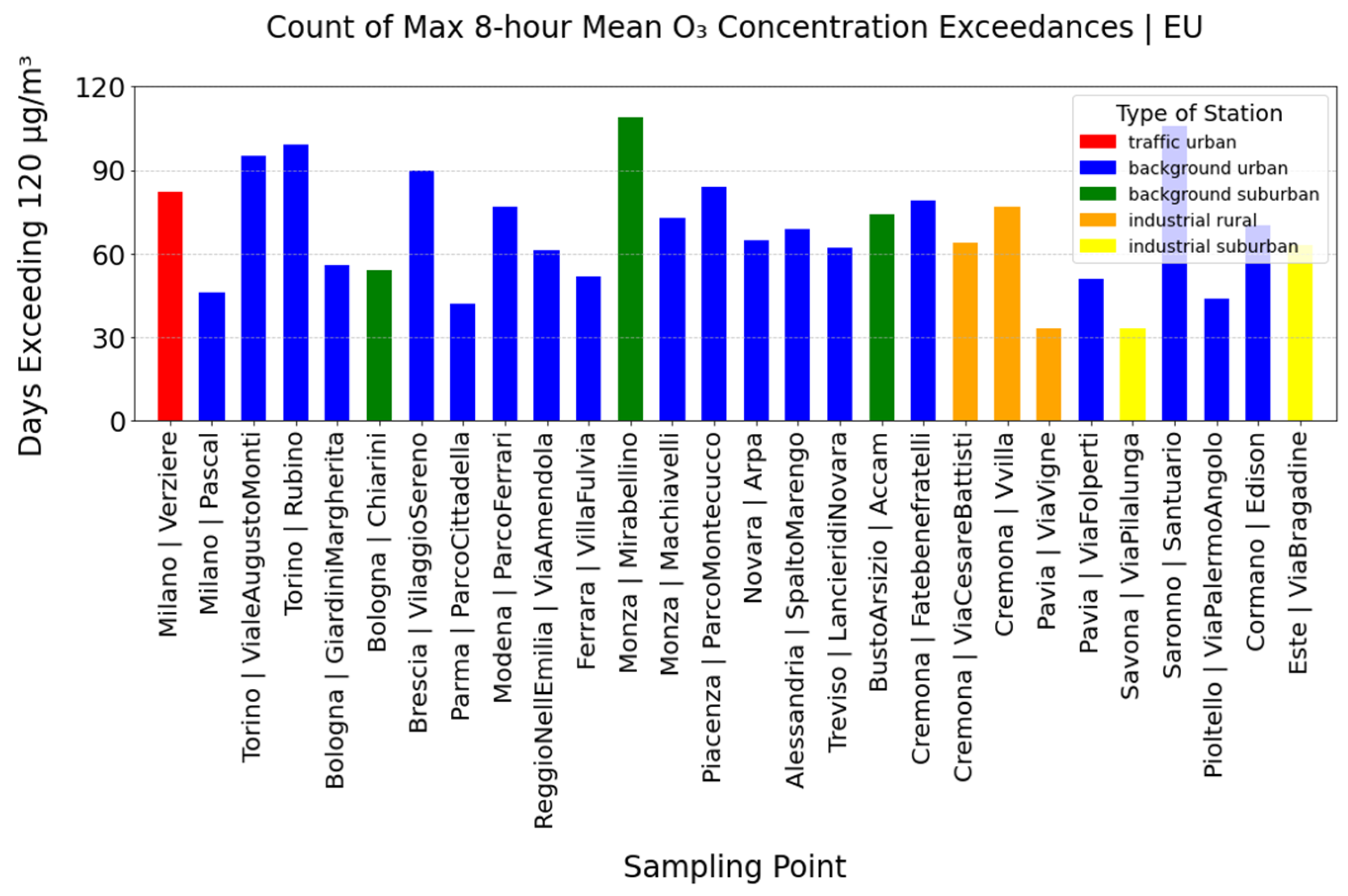

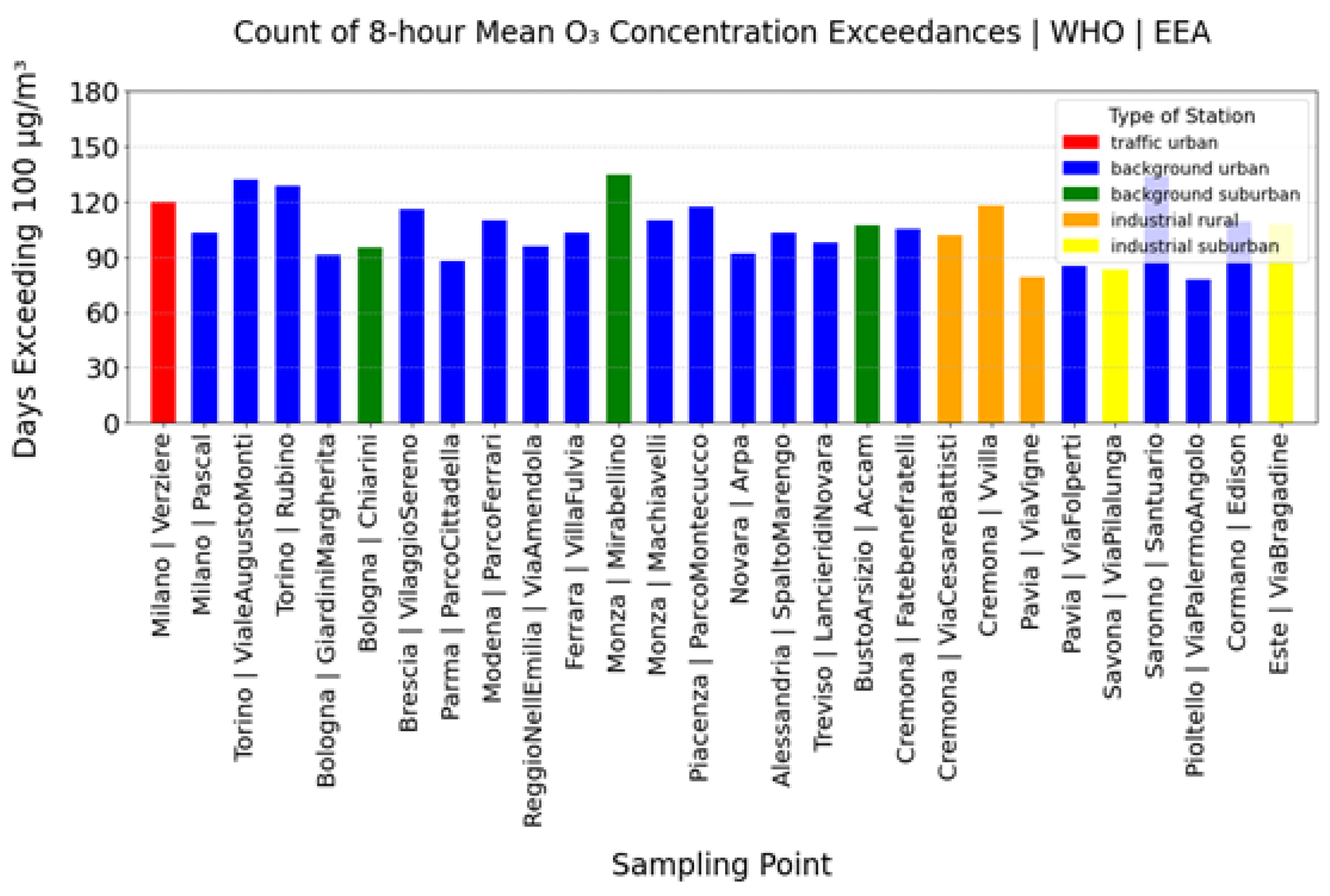

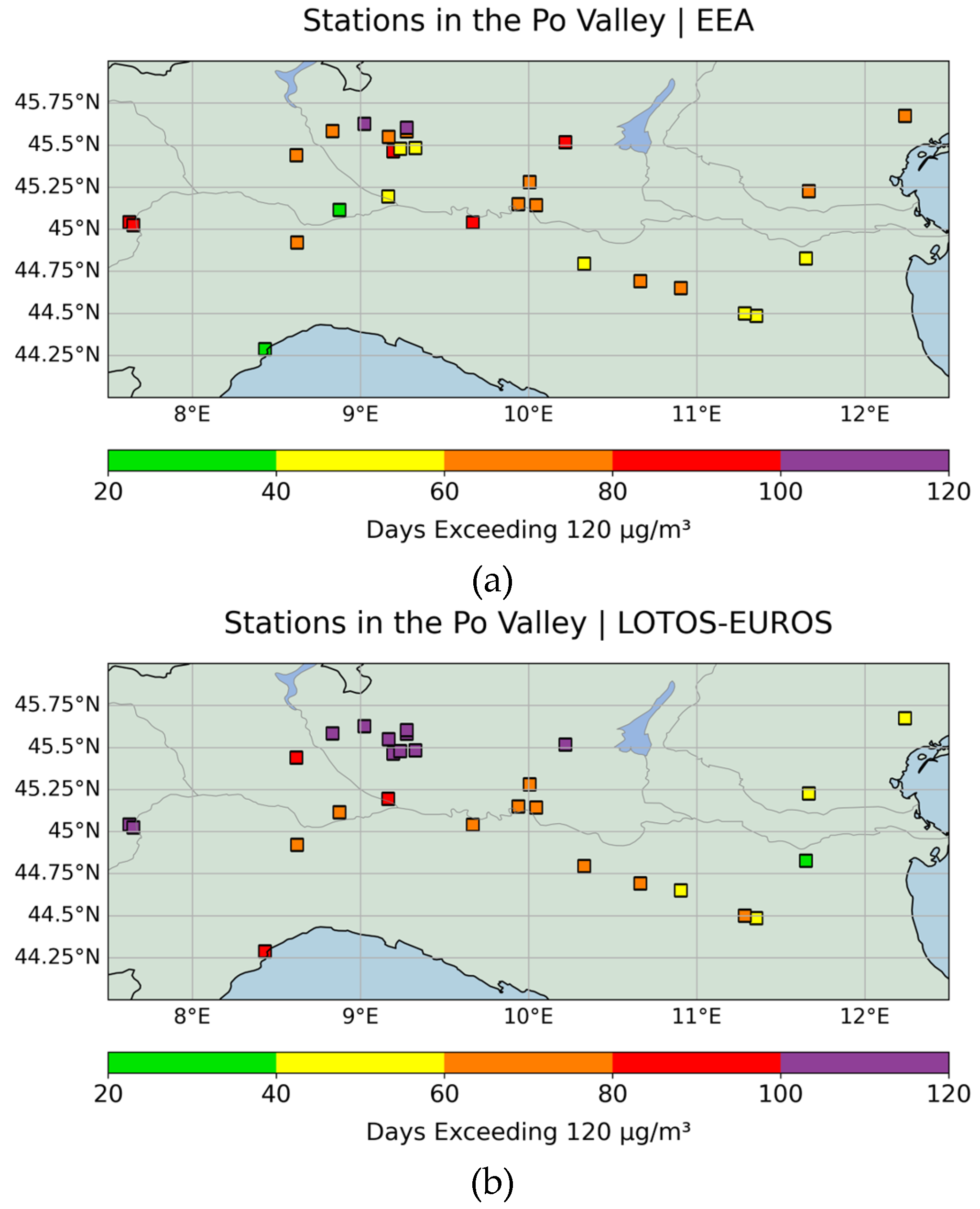

3.1. Surface Air Quality Assessment

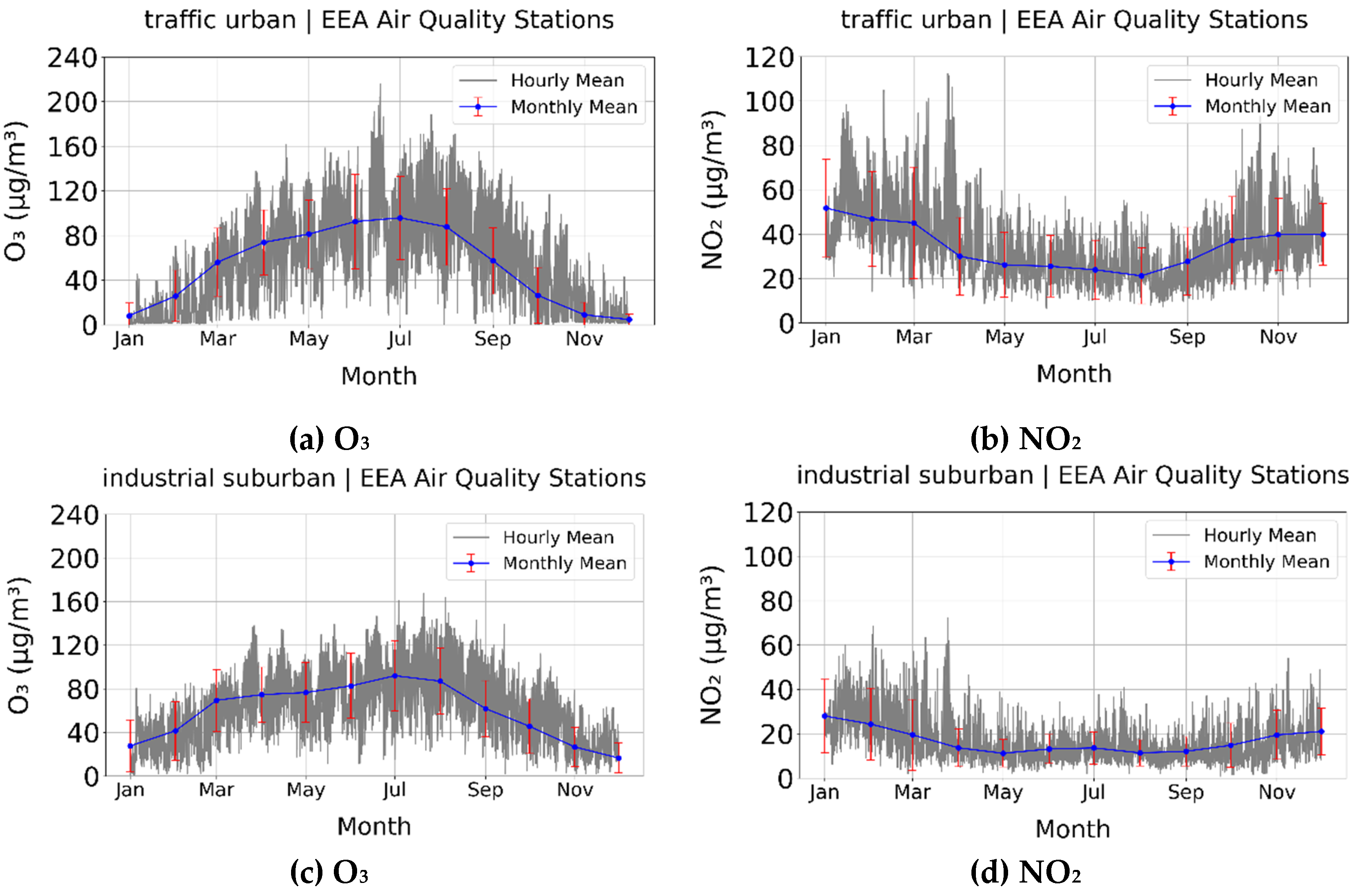

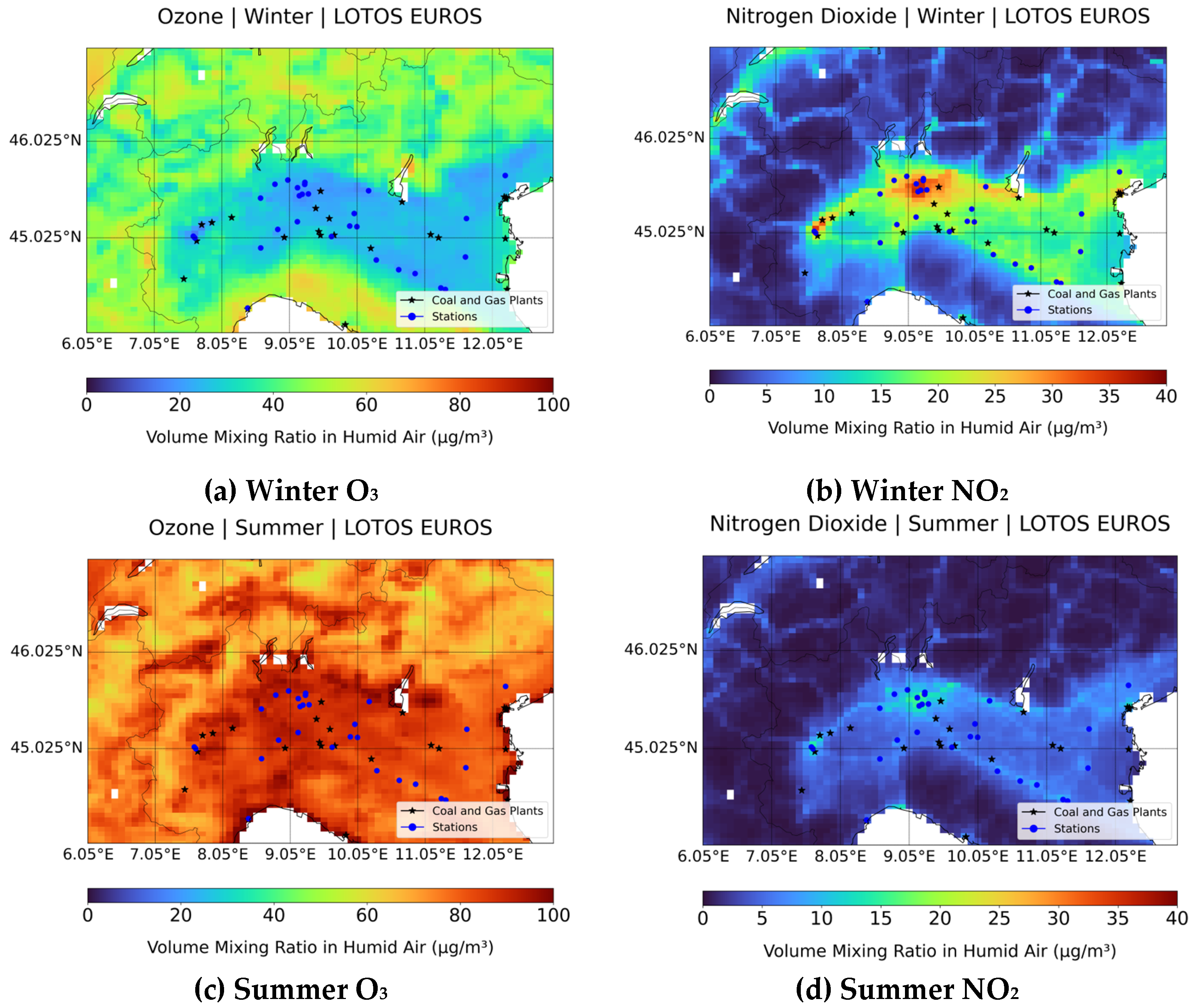

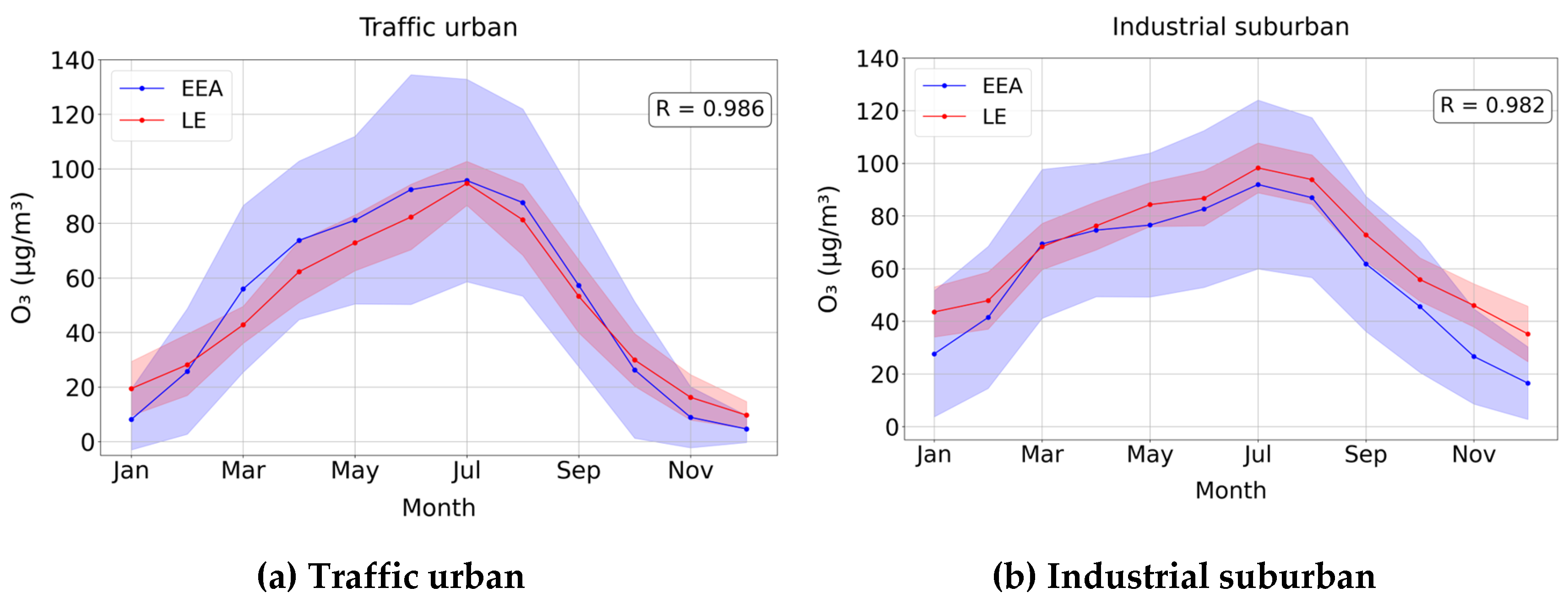

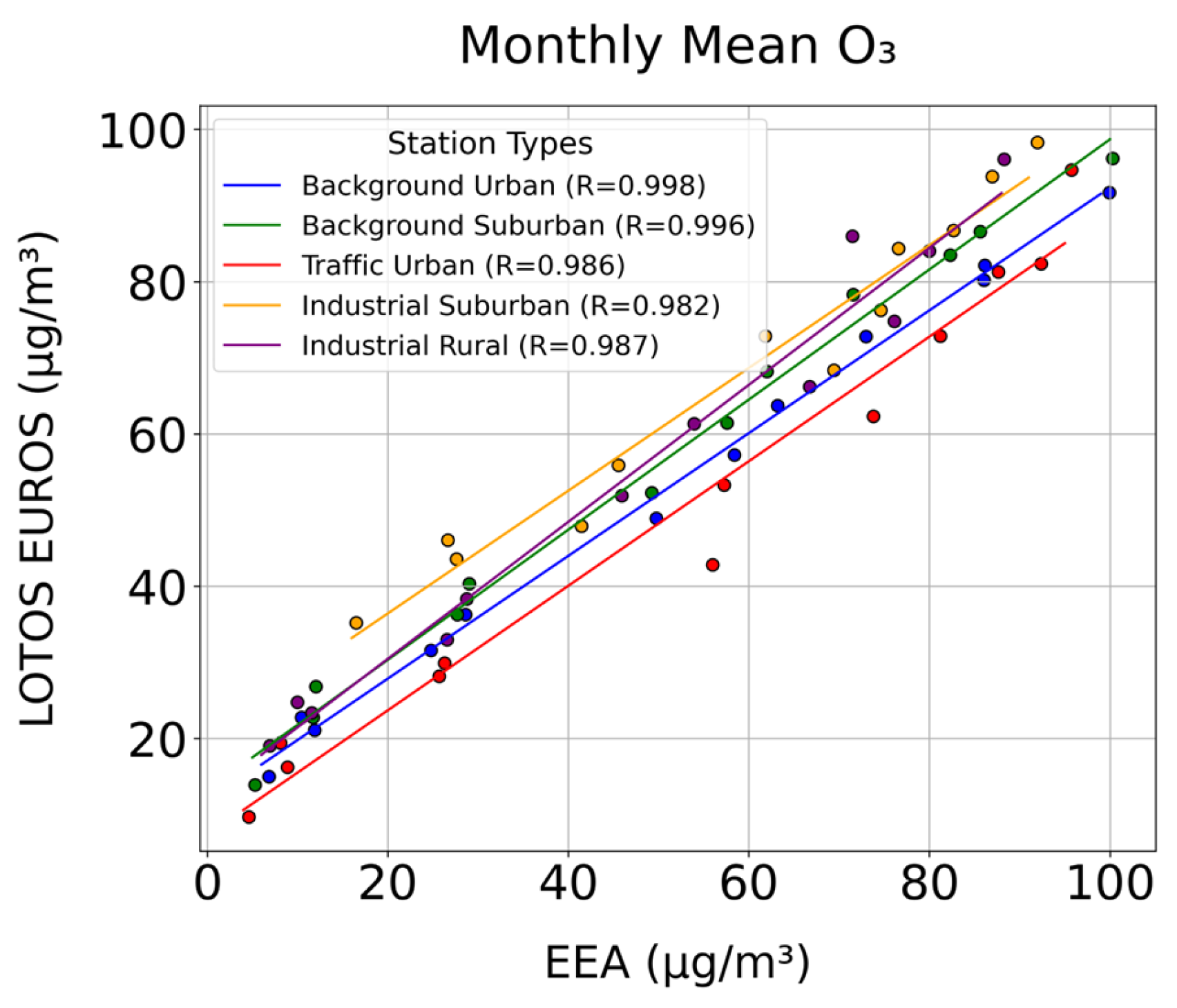

3.1.1. Monthly Mean Comparisons

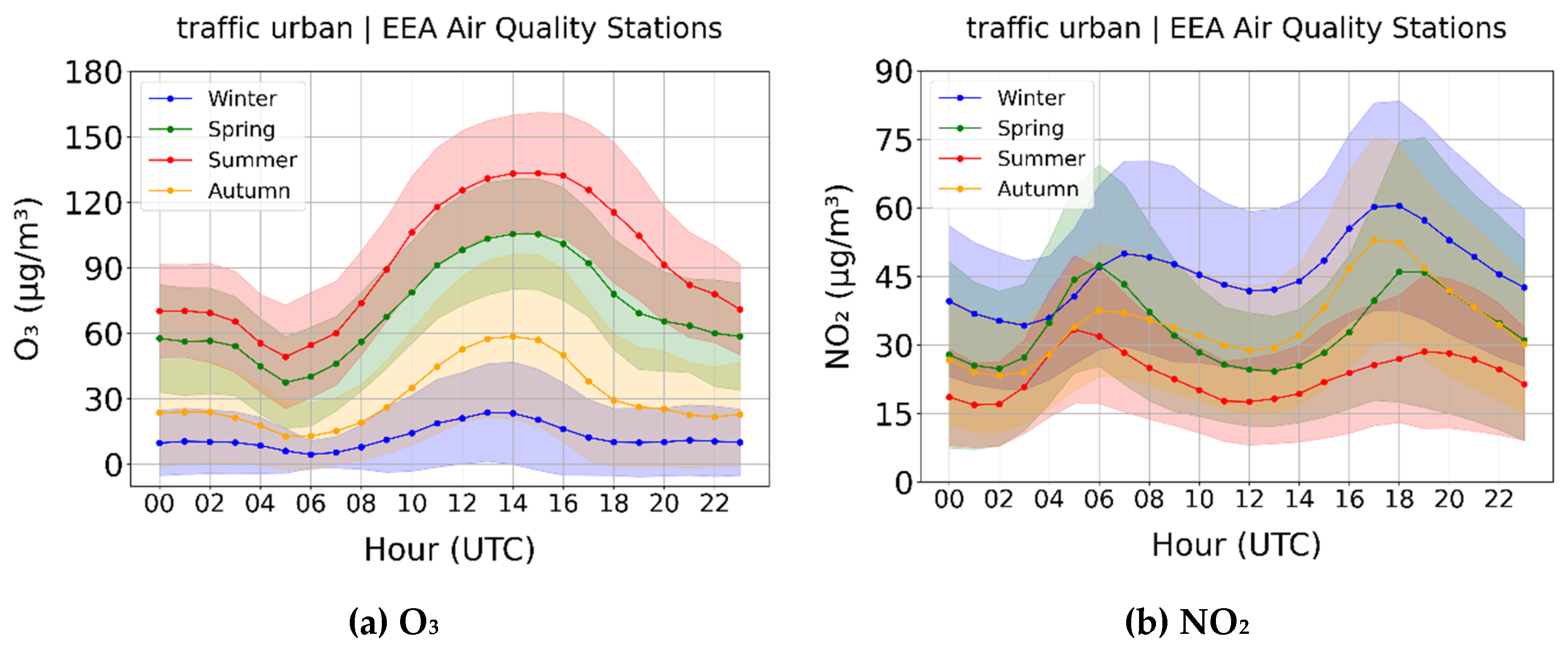

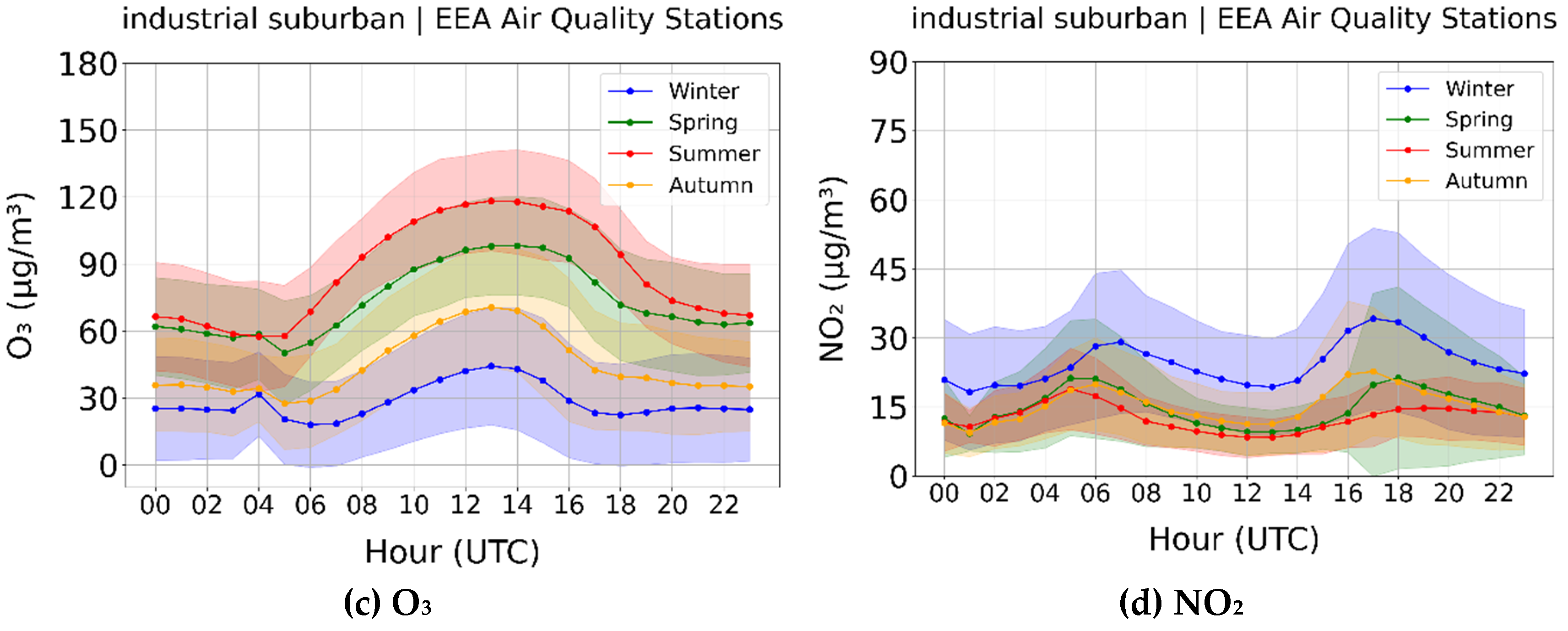

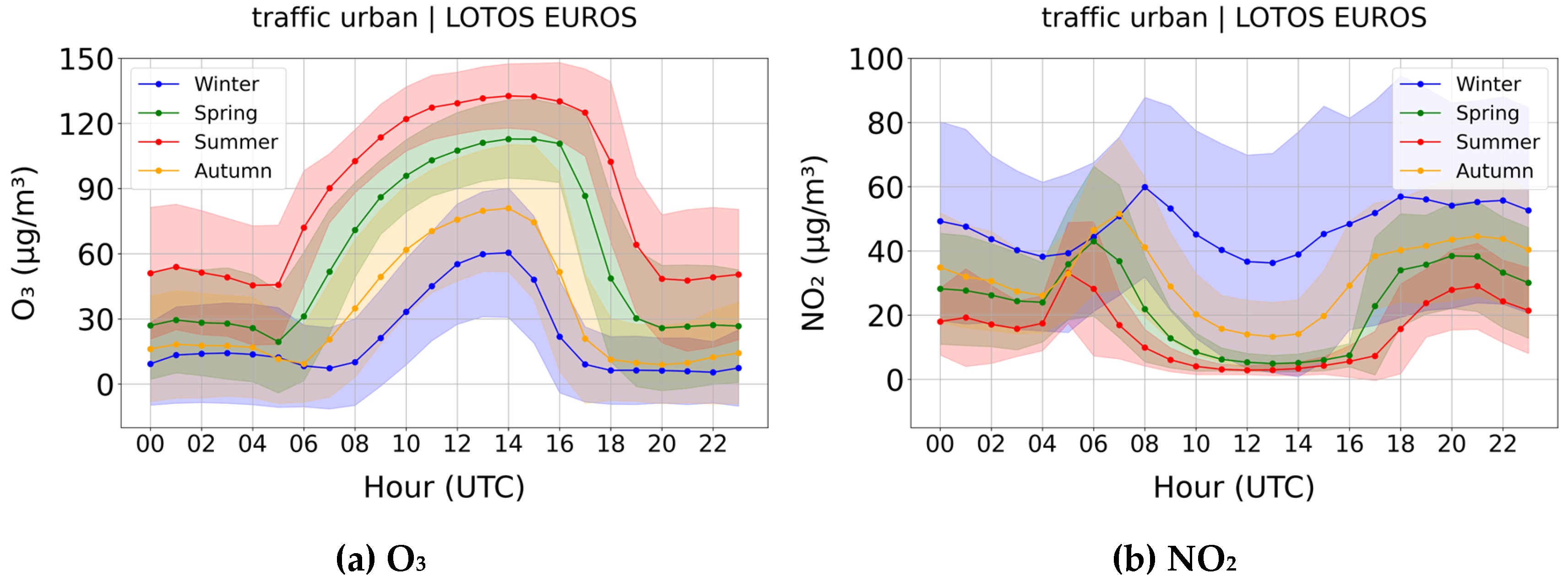

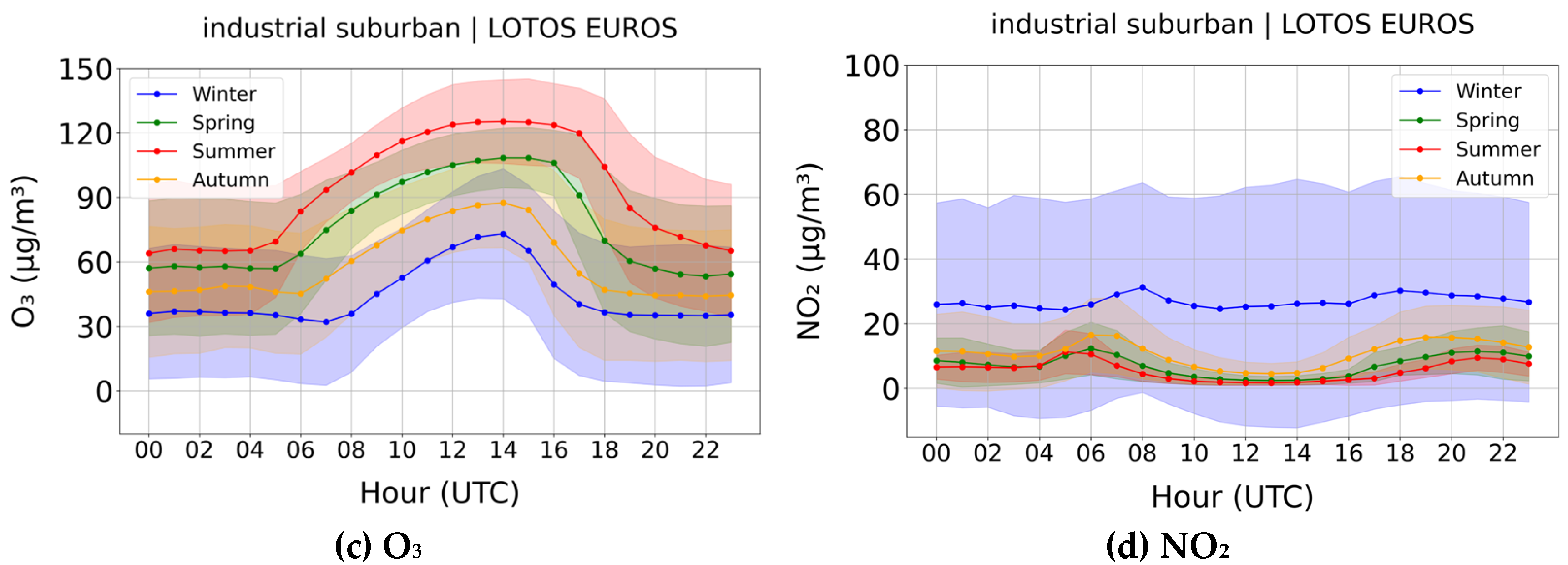

3.1.2. Seasonal and Diurnal Comparisons

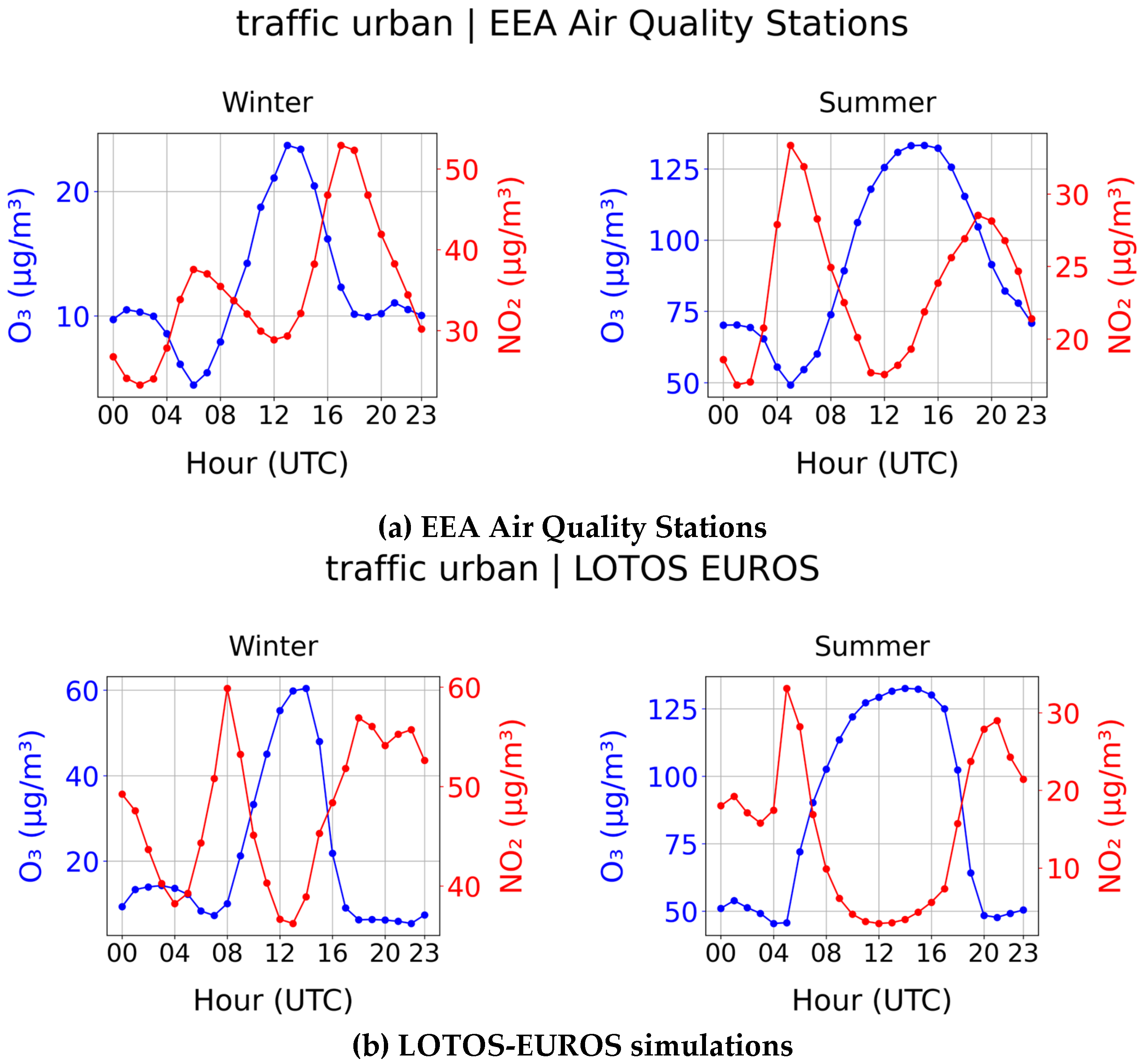

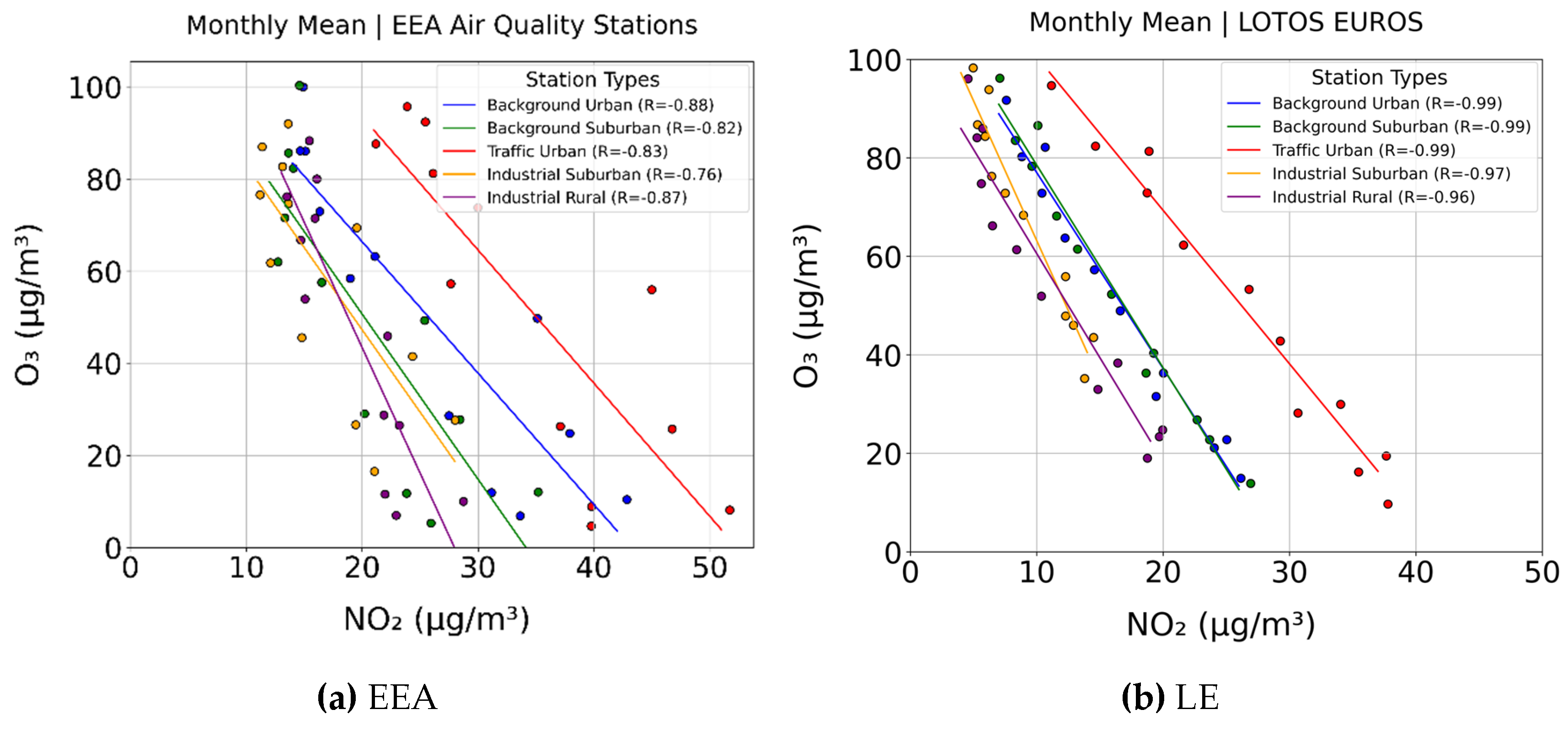

3.1.3. Co-Variability of Ozone and Nitrogen Dioxide Levels

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- LOTOS-EUROS CTM simulations showed a strong correlation with EEA measurements (R > 0.98) on a monthly mean basis and R values between 0.83 and 0.98 on a seasonal diurnal temporal scale, indicating that the LOTOS-EUROS model is highly effective at capturing the spatiotemporal temporal patterns and overall seasonal trends of ozone concentrations.

- The inverse correlation between ozone and nitrogen dioxide surface levels reported by the EEA in situ measurements reports high R values from -0.76 to -0.88 while the CTM, due to the spatial resolution of the simulations which disable the identification of local effects, reports higher correlations of -0.96 to -0.99.

- The consistent overestimation of ozone concentrations during its morning peak levels in January and February 2022 identified in this work remains a point for further investigation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sampling Point | Name/Locality | City | Station Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPO.IT0705A | Verziere | Milano | Traffic urban |

| SPO.IT0706A | Via Palermo Angolo | Pioltello | Background urban |

| SPO.IT0804A | Parco Cittadella | Parma | Background urban |

| SPO.IT0842A | V. villa | Cremona | Industrial rural |

| SPO.IT0892A | Giardini Margherita | Bologna | Background urban |

| SPO.IT0912A | Via Folperti | Pavia | Background urban |

| SPO.IT0940A | Via Amendola | Reggio N. Emilia | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1144A | Via Pilalunga | Savona | Industrial suburban |

| SPO.IT1459A | Accam | Busto Arsizio | Background suburban |

| SPO.IT1590A | Lancieridi Novara | Treviso | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1650A | Santuario | Saronno | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1692A | Pascal | Milan | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1737A | Vilaggio Sereno | Brescia | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1739A | Fatebene fratelli | Cremona | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1743A | Machiavelli | Monza | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1746A | Via Vigne | Pavia | Industrial rural |

| SPO.IT1771A | Parco Ferrari | Modena | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1830A | Spalto Marengo | Alessandria | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1871A | Via Bragadine | Este | Industrial suburban |

| SPO.IT1877A | Rubino | Torino | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1918A | Villa Fulvia | Ferrara | Background urban |

| SPO.IT1975A | Parco Montecucco | Piacenza | Background urban |

| SPO.IT2063A | Via Cesare Battisti | Cremona | Industrial rural |

| SPO.IT2075A | Chiarini | Bologna | Background suburban |

| SPO.IT2098A | Mirabellino | Monza | Background suburban |

| SPO.IT2168A | Viale Augusto Monti | Torino | Background urban |

| SPO.IT2232A | Edison | Cormano | Background urban |

| SPO.IT2282A | Arpa | Novara | Background urban |

Appendix B

References

- Sharma, A.K., Sharma, M., Sharma, A.K., Sharma, M. and Sharma, M. (2023). Mapping the impact of environmental pollutants on human health and environment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 255, pp.107325–107325. [CrossRef]

- Husain, L., Coffey, P.E., Meyers, R.E. and Cederwall, R.T. (1977). Ozone transport from stratosphere to troposphere. Geophysical Research Letters, 4(9), pp.363–365. [CrossRef]

- Stohl, A. and Trickl, T. (2006). Long-Range Transport of Ozone from the North American Boundary Layer to Europe: Observations and Model Results. Kluwer Academic Publishers eBooks, [online] pp.257–266. [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J. (1979). The Role of NO and NO2 in the Chemistry of the Troposphere and Stratosphere. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 7(1), pp.443–472. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Cheng, X., Liu, J., Chen, Z., Wang, H., Deng, H., Hu, J., Jiang, Y., Yang, M., Gai, C. and Cheng, Z. (2024). Comparison of Surface Ozone Variability in Mountainous Forest Areas and Lowland Urban Areas in Southeast China. Atmosphere, [online] 15(5), pp.519–519. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, K.A.K., Nishanth, T., Kumar, S. and Valsaraj, K.T. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of Surface Ozone Variations in Several Indian Hotspots. Atmosphere, [online] 15(7), pp.852–852. [CrossRef]

- O. Badr and S.D. Probert (1993). Oxides of nitrogen in the Earth’s atmosphere: Trends, sources, sinks and environmental impacts. Applied Energy, 46(1), pp.1–67. [CrossRef]

- Monks, P.S, A.T. Archibald, A. Colette, O. Cooper, M. Coyle, R. Derwent, D. Fowler, C. Granier, K.S. Law, G.E. Mills, D.S. Stevenson, O. Tarasova, V. Thouret, E. von Schneidemesser, R. Sommariva, O. Wild and M.L. Williams (2015). Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, [online] 15(15), pp.8889–8973. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Cheng, X., Liu, J., Chen, Z., Wang, H., Deng, H., Hu, J., Jiang, Y., Yang, M., Gai, C. and Cheng, Z. (2024). Comparison of Surface Ozone Variability in Mountainous Forest Areas and Lowland Urban Areas in Southeast China. Atmosphere, [online] 15(5), pp.519–519. [CrossRef]

- Koukouli, M.-E., Pseftogkas, A., Karagkiozidis, D., Skoulidou, I., Drosoglou, T., Balis, D., Bais, A.F., Melas, D. and Hatzianastassiou, N. (2022). Air Quality in Two Northern Greek Cities Revealed by Their Tropospheric NO2 Levels. 13(5), pp.840–840. [CrossRef]

- Po Valley. [online] Available at: https://geography.name/po-valley/.

- Pivato, A., Pegoraro, L., Masiol, M., Bortolazzo, E., Bonato, T., Formenton, G., Cappai, G., Beggio, G. and Giancristofaro, R.A. (2023). Long time series analysis of air quality data in the Veneto region (Northern Italy) to support environmental policies. Atmospheric Environment, [online] 298, p.119610. [CrossRef]

- Masiol, M., Squizzato, S., Formenton, G., Harrison, R.M. and Agostinelli, C. (2017). Air quality across a European hotspot: Spatial gradients, seasonality, diurnal cycles and trends in the Veneto region, NE Italy. Science of The Total Environment, 576, pp.210–224. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (n.d.). Air Quality. [online] environment.ec.europa.eu. Available at: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/air/air-quality_en.

- World Health Organization (2021). What are the WHO Air quality guidelines? [online] World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/what-are-the-who-air-quality-guidelines.

- Benassi, A., Dalan, F., Alessandro Gnocchi, Maffeis, G., Giampiero Malvasi, Liguori, F., Pernigotti, D., Pillon, S., Sansone, M. and Susanetti, L. (2011). A one-year application of the Veneto air quality modelling system: regional concentrations and deposition on Venice lagoon. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 44(1/2/3/4), pp.32–32. [CrossRef]

- Martilli, A., A. Neftel, G. Favaro, F. Kirchner, S. Sillman, and A. Clappier, Simulation of the ozone formation in the northern part of the Po Valley, J. Geophys. Res., 107(D22), 8195, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A., Ghermandi, G. and Harrison, R.M. (2012). Analysis of the air pollution climate at a background site in the Po valley. J. Environ. Monit., 14(2), pp.552–563. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J., Wolfe, G. M., Bohn, B., Broch, S., Fuchs, H., Ganzeveld, L. N., Gomm, S., Häseler, R., Hofzumahaus, A., Holland, F., Jäger, J., Li, X., Lohse, I., Lu, K., Prévôt, A. S. H., Rohrer, F., Wegener, R., Wolf, R., Mentel, T. F., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Wahner, A., and Keutsch, F. N.: Evidence for an unidentified non-photochemical ground-level source of formaldehyde in the Po Valley with potential implications for ozone production, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 1289–1298, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Maurizi, A., Russo, F. and Tampieri, F. (2013). Local vs. external contribution to the budget of pollutants in the Po Valley (Italy) hot spot. Science of The Total Environment, 458-460, pp.459–465. [CrossRef]

- Lonati, G. and Riva, F. (2021). Regional Scale Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Air Quality: Gaseous Pollutants in the Po Valley, Northern Italy. Atmosphere, 12(2), p.264. [CrossRef]

- Thunis, P., Triacchini, G., White, L., Maffeis, G. and Volta, M. (2009). Air pollution and emission reductions over the Po-valley: Air quality modelling and integrated assessment. [online] 18th World IMACS / MODSIM. Available at: https://mssanz.org.au/modsim09/F10/thunis.pdf [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

- Zhu, T., Melamed, M.L., Parrish, D., Gllardo Klenner, L., Lawrence, M., Konare, A. and Liousse, C. (eds) (2012) WMO/IGAC Impacts of Megacities on Air Pollution and Climate. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization, ISBN: 978-0-9882867-0-2, pp.299.

- Topographic-map.com (2024). Po Valley topographic map, elevation, terrain. [online] Topographic maps. Available at: https://en-us.topographic-map.com/map-6ffntf/Po-Valley/ [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

- Caserini, S., Giani, P., Cacciamani, C., Ozgen, S. and Lonati, G. (2017). Influence of climate change on the frequency of daytime temperature inversions and stagnation events in the Po Valley: historical trend and future projections. Atmospheric Research, 184, pp.15–23. [CrossRef]

- Masiol, M., Agostinelli, C., Formenton, G., Tarabotti, E. and Pavoni, B. (2014). Thirteen years of air pollution hourly monitoring in a large city: Potential sources, trends, cycles and effects of car-free days. Science of The Total Environment, 494-495, pp.84–96. [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A. and Ghermandi, G. (2014). Long-term trend and variability of atmospheric PM10 concentration in the Po Valley. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 14(10), pp.4895–4907. [CrossRef]

- Serio, C., Masiello, G. and Cersosimo, A. (2022). NO2 pollution over selected cities in the Po valley in 2018–2021 and its possible effects on boosting COVID-19 deaths. Heliyon, 8(8), p.e09978. [CrossRef]

- Schaap, M., Timmermans, R.M.A., Roemer, M., Boersen, G.A.C., Builtjes, P.J.H., Sauter, F.J., Velders, G.J.M. and Beck, J.P. (2008). The LOTOS–EUROS model: description, validation and latest developments. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 32(2), pp.270–290.

- Manders, A.M.M., Builtjes, P.J.H., Curier, L., Denier van der Gon, H.A.C., Hendriks, C., Jonkers, S., Kranenburg, R., Kuenen, J.J.P., Segers, A.J., Timmermans, R.M.A., Visschedijk, A.J.H., Wichink Kruit, R.J., van Pul, W.A.J., Sauter, F.J., van der Swaluw, E., Swart, D.P.J., Douros, J., Eskes, H., van Meijgaard, E. and van Ulft, B. (2017). Curriculum vitae of the LOTOS–EUROS (v2.0) chemistry transport model. Geoscientific Model Development, [online] 10(11), pp.4145–4173. [CrossRef]

- Skoulidou, I., Koukouli, M.-E., Manders, A., Segers, A., Karagkiozidis, D., Gratsea, M., Balis, D., Bais, A., Gerasopoulos, E., Stavrakou, T., Geffen, J. van, Eskes, H. and Richter, A. (2021). Evaluation of the LOTOS-EUROS NO2 simulations using ground-based measurements and S5P/TROPOMI observations over Greece. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 21(7), pp.5269–5288. [CrossRef]

- Pseftogkas, A., Koukouli, M.-E., Segers, A., Manders, A., Geffen, J. van, Balis, D., Meleti, C., Stavrakou, T. and Eskes, H. (2022). Comparison of S5P/TROPOMI Inferred NO2 Surface Concentrations with In Situ Measurements over Central Europe. Remote Sensing, 14(19), p.4886. [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M., Segers, A., Kranenburg, R., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Borge, R., de la Paz, D., Gangoiti, G. and Schaap, M. (2019). Analysis of summer O3 in the Madrid air basin with the LOTOS-EUROS chemical transport model. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, [online] 19(22), pp.14211–14232. [CrossRef]

- Curier, R.L., Timmermans, R., Calabretta-Jongen, S., Eskes, H., Segers, A., Swart, D. and Schaap, M. (2012). Improving ozone forecasts over Europe by synergistic use of the LOTOS-EUROS chemical transport model and in-situ measurements. Atmospheric environment, 60, pp.217–226. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M. and Chiara, G. (2020). The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 146(730). [CrossRef]

- Kuenen, J., Dellaert, S., Visschedijk, A., Jalkanen, J.-P., Super, I. and Denier van der Gon, H. (2022). CAMS-REG-v4: a state-of-the-art high-resolution European emission inventory for air quality modelling. Earth System Science Data, [online] 14(2), pp.491–515. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus, E. (2023). Copernicus Atmosphere CAMS2_61 -Global and European emission inventories Documentation of CAMS emission inventory products. [online]. [CrossRef]

- www.eumetsat.int. (2020). Metop Series | EUMETSAT Website. [online] Available at: https://www.eumetsat.int/our-satellites/metop-series.

- Aeris-data.fr. (2024). IASI – aeris. [online] Available at: https://www.aeris-data.fr/en/projects/iasi-2/ [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

- Hurtmans, D., Coheur, P.-F., Wespes, C., Clarisse, L., Scharf, O., Clerbaux, C., Hadji-Lazaro, J., George, M. and Solène Turquety (2012). FORLI radiative transfer and retrieval code for IASI. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer, 113(11), pp.1391–1408. [CrossRef]

- Acsaf.org. (2024). AC SAF - IASI information. [online] Available at: https://acsaf.org/iasi.php [Accessed 15 Dec. 2024].

- Boynard, A., Hurtmans, D., Garane, K., Goutail, F., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Koukouli, M. E., Wespes, C., Vigouroux, C., Keppens, A., Pommereau, J.-P., Pazmino, A., Balis, D., Loyola, D., Valks, P., Sussmann, R., Smale, D., Coheur, P.-F., and Clerbaux, C.: Validation of the IASI FORLI/EUMETSAT ozone products using satellite (GOME-2), ground-based (Brewer–Dobson, SAOZ, FTIR) and ozonesonde measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 5125–5152, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhou, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, K. and Xiu, G. (2020). Investigating the photolysis of NO2 and influencing factors by using a DFT/TD-DFT method. Atmospheric Environment, 230, p.117559. [CrossRef]

- Jenkin, M.E. and Clemitshaw, K.C. (2002). Chapter 11 Ozone and other secondary photochemical pollutants: chemical processes governing their formation in the planetary boundary layer. Developments in Environmental Science, pp.285–338. [CrossRef]

- Wayne, R.P., Barnes, I., Biggs, P., Burrows, J.P., Canosa-Mas, C.E., Hjorth, J., Le Bras, G., Moortgat, G.K., Perner, D., Poulet, G., Restelli, G. and Sidebottom, H. (1991). The nitrate radical: Physics, chemistry, and the atmosphere. Atmospheric Environment. Part A. General Topics, 25(1), pp.1–203. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. and Arey, J. (2003). Gas-phase tropospheric chemistry of biogenic volatile organic compounds: a review. Atmospheric Environment, 37, pp.197–219. [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. (2009). An introduction to boundary layer meteorology. New York: Springer.

- Jacob, D.J. (1999). Introduction to atmospheric chemistry. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Jia, M., Zhao, T., Cheng, X., Gong, S., Zhang, X., Tang, L., Liu, D., Wu, X., Wang, L. and Chen, Y. (2017). Inverse Relations of PM2.5 and O3 in Air Compound Pollution between Cold and Hot Seasons over an Urban Area of East China. Atmosphere, 8(12), p.59. [CrossRef]

- Strode, S.A., Ziemke, J.R., Oman, L.D., Lamsal, L.N., Olsen, M.A. and Liu, J. (2019). Global changes in the diurnal cycle of surface ozone. Atmospheric Environment, 199, pp.323–333. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., Zhang, L. and Shen, L. (2019). Meteorology and Climate Influences on Tropospheric Ozone: a Review of Natural Sources, Chemistry, and Transport Patterns. Current Pollution Reports, 5(4), pp.238–260. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.T., Apituley, A., Mettig, N., Kreher, K., Knowland, K.E., Allaart, M., Piters, A., Van Roozendael, M., Veefkind, P., Ziemke, J.R., Kramarova, N., Weber, M., Rozanov, A., Twigg, L., Sumnicht, G. and McGee, T.J. (2022). Tropospheric and stratospheric ozone profiles during the 2019 TROpomi vaLIdation eXperiment (TROLIX-19). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, [online] 22(17), pp.11137–11153. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, Z.M., Archer-Nicholls, S., Beig, G., Folberth, G.A., Sudo, K., Abraham, N.L., Ghude, S.D., Henze, D.K. and Archibald, A.T. (2019). Evaluation of tropospheric ozone and ozone precursors in simulations from the HTAPII and CCMI model intercomparisons – a focus on the Indian subcontinent. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 19(9), pp.6437–6458. [CrossRef]

- Spirig, C., A. Neftel, L. I. Kleinman, and J. Hjorth, NOx versus VOC limitation of O3 production in the Po valley: Local and integrated view based on observations, J. Geophys. Res., 107(D22), 8191, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Clerbaux, C., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Solène Turquety, George, M., Boynard, A., Pommier, M., Safieddine, S., Pierre-François Coheur, Hurtmans, D., Lieven Clarisse and Martin Van Damme (2015). Tracking pollutants from space: Eight years of IASI satellite observation. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 347(3), pp.134–144. [CrossRef]

- Keppens, A., Compernolle, S., Verhoelst, T., Hubert, D., and Lambert, J.-C.: Harmonization and comparison of vertically resolved atmospheric state observations: methods, effects, and uncertainty budget, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 4379–4391, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Beirle, S., Platt, U., Wenig, M., and Wagner, T.: Weekly cycle of NO2 by GOME measurements: a signature of anthropogenic sources, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 3, 2225–2232, 2003. [CrossRef]

| Station Type | Annual O₃ | Monthly O₃ | Annual NO2 | Monthly NO2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mean ± 1σ) | max | min | (mean ± 1σ) | max | min | |

| Background urban | 49.90 ± 32.82 | 99.94 | 6.82 | 25.76 ± 10.14 | 42.84 | 14.65 |

| Background suburban | 49.52 ± 32.12 | 100.27 | 5.27 | 20.31 ± 7.35 | 35.18 | 12.74 |

| Traffic urban | 51.46 ± 35.11 | 95.72 | 4.61 | 34.53 ± 10.13 | 51.71 | 21.16 |

| Industrial suburban | 58.47 ± 25.97 | 91.96 | 16.50 | 16.85 ± 5.52 | 28.01 | 11.19 |

| Industrial rural | 47.18 ± 29.64 | 88.28 | 6.93 | 19.30 ± 4.76 | 28.73 | 13.50 |

| R Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station Type | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | |

| Background urban | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.97 | |

| Background suburban | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | |

| Traffic urban | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.87 | |

| Industrial suburban | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.97 | |

| Industrial rural | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).