Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

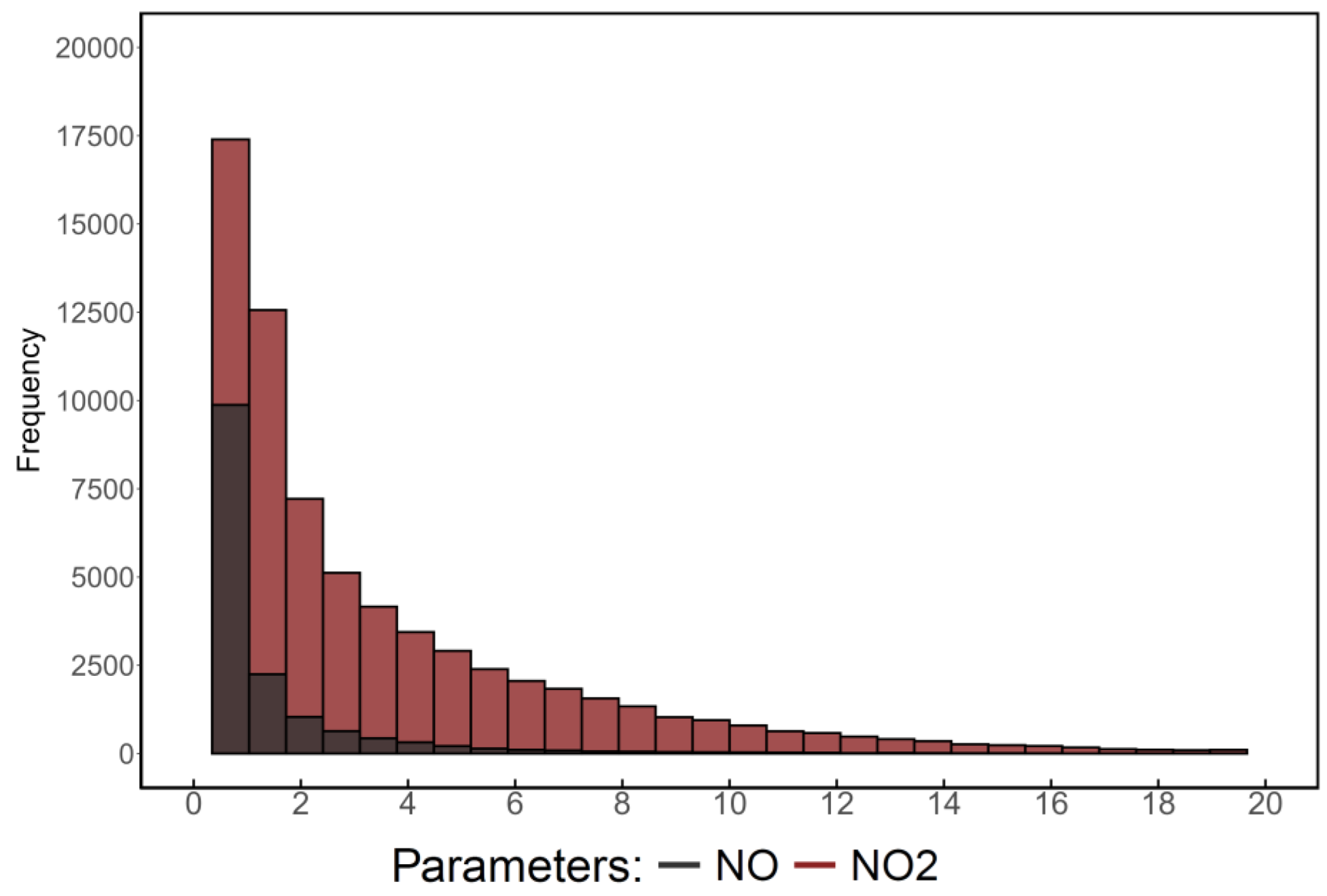

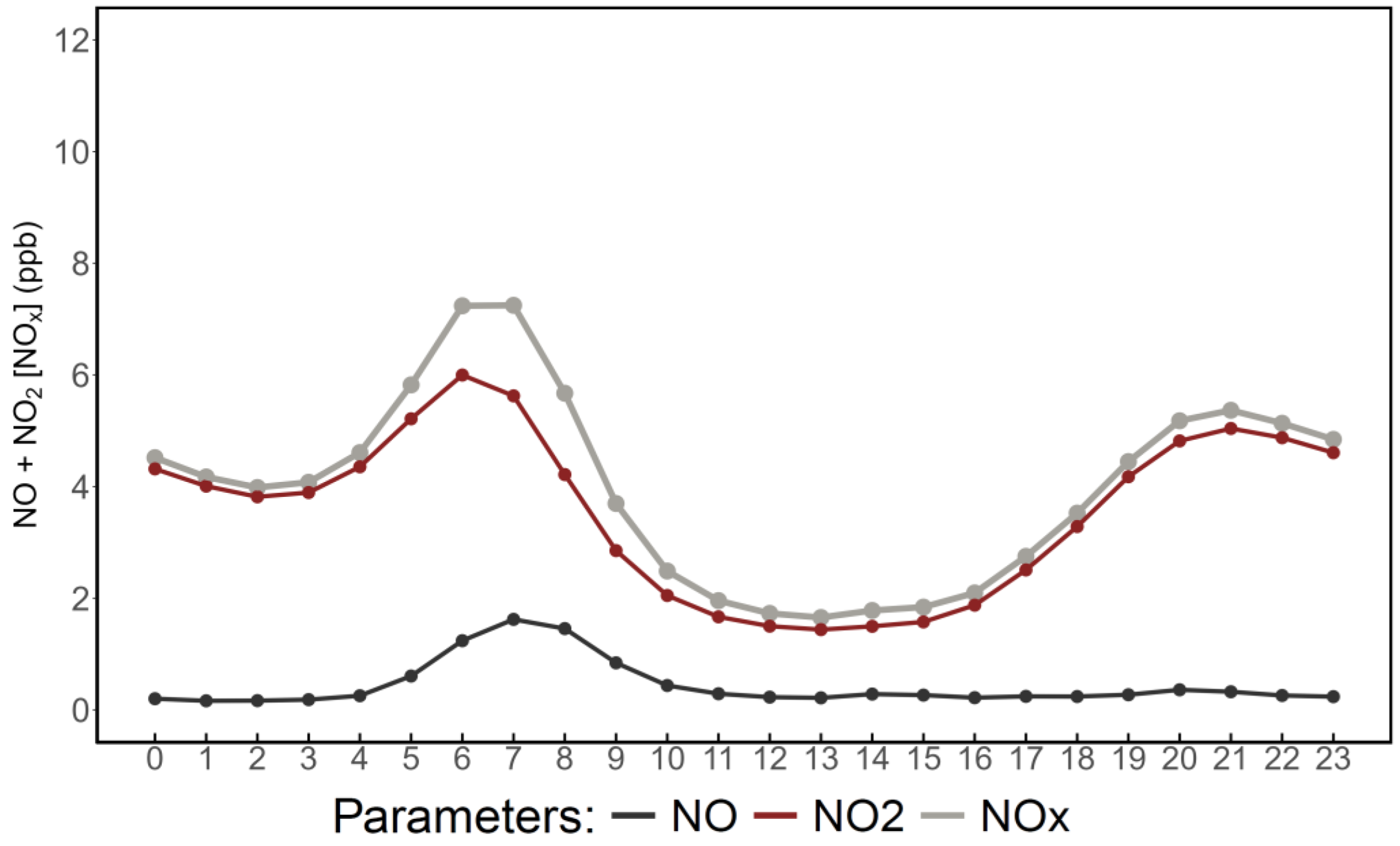

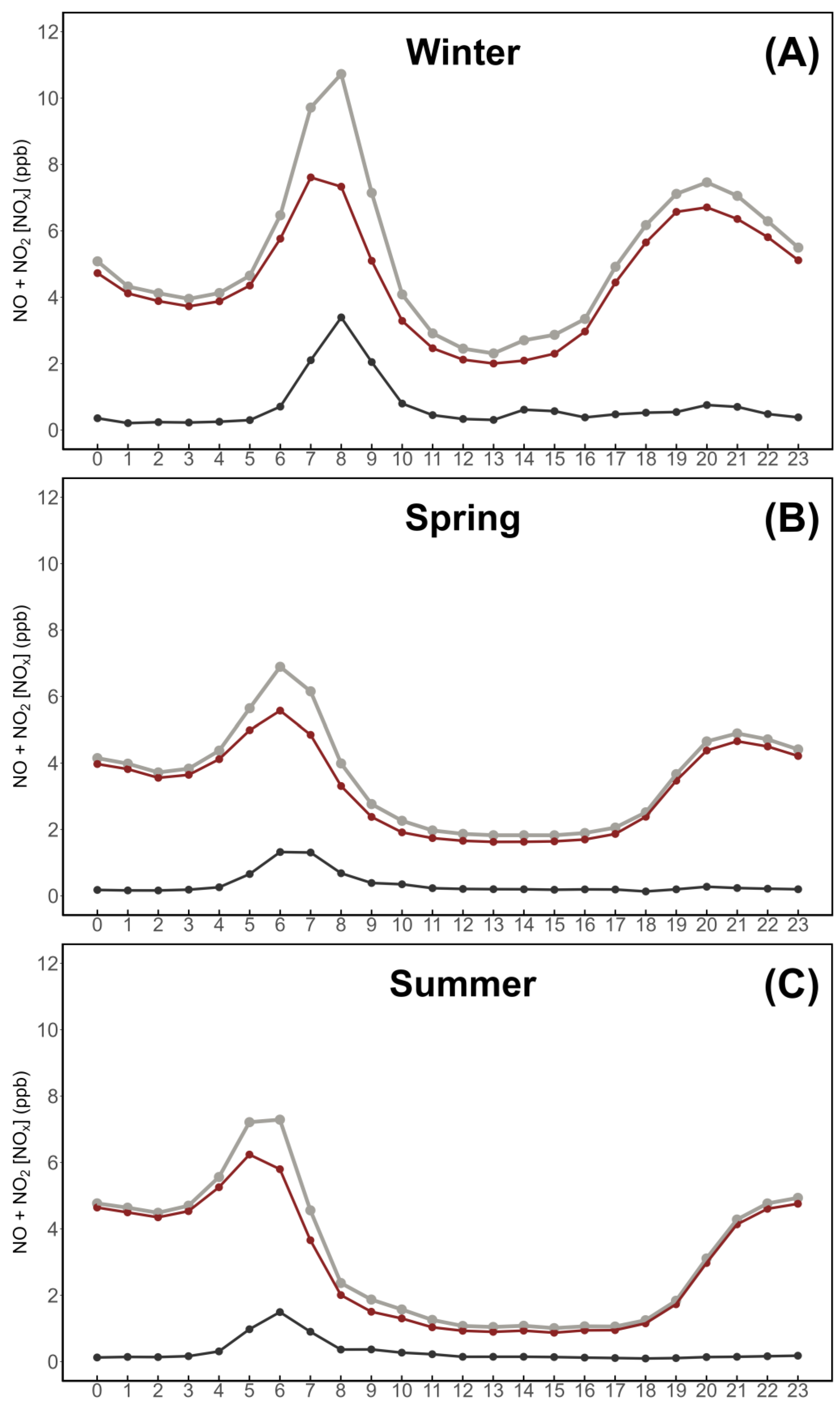

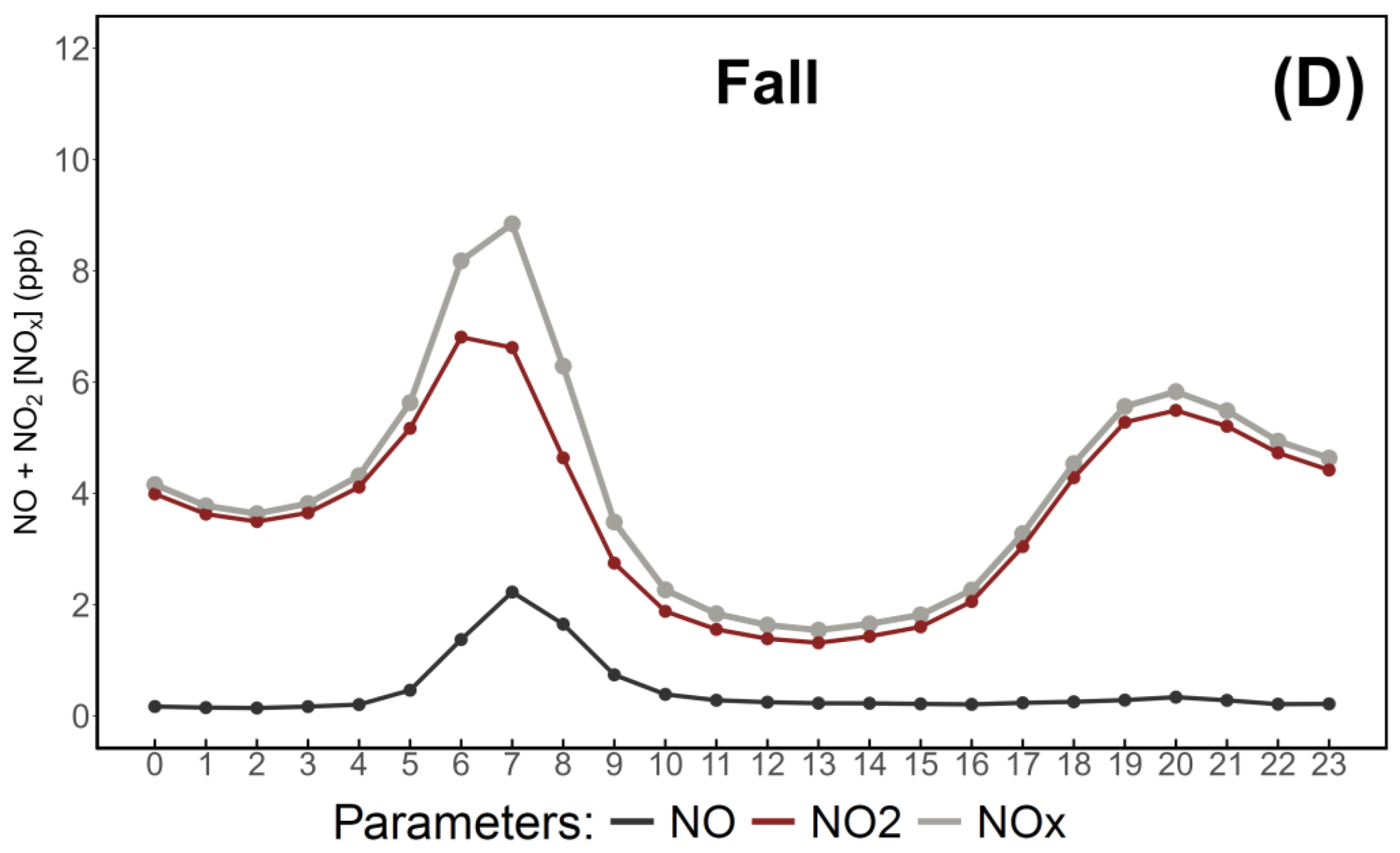

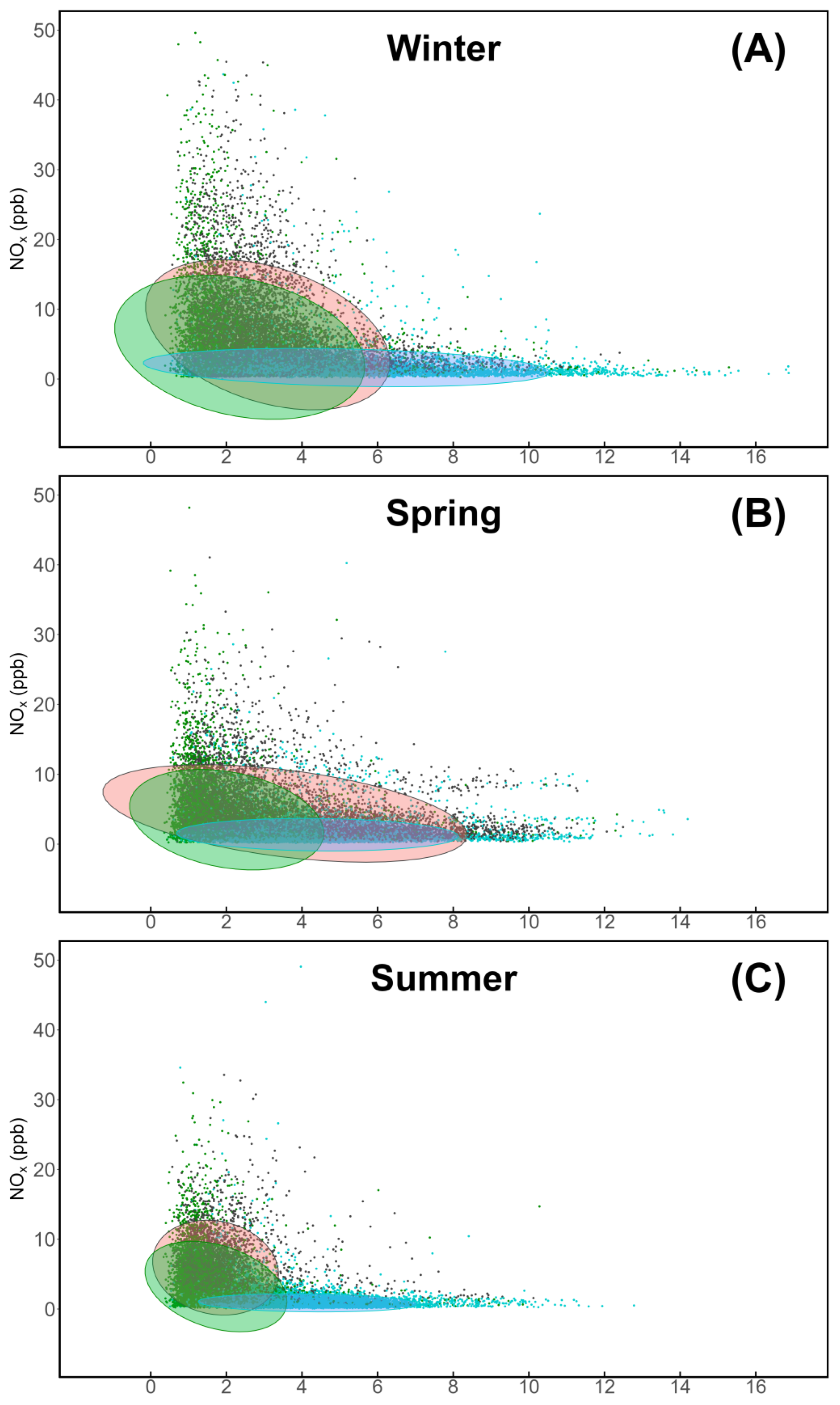

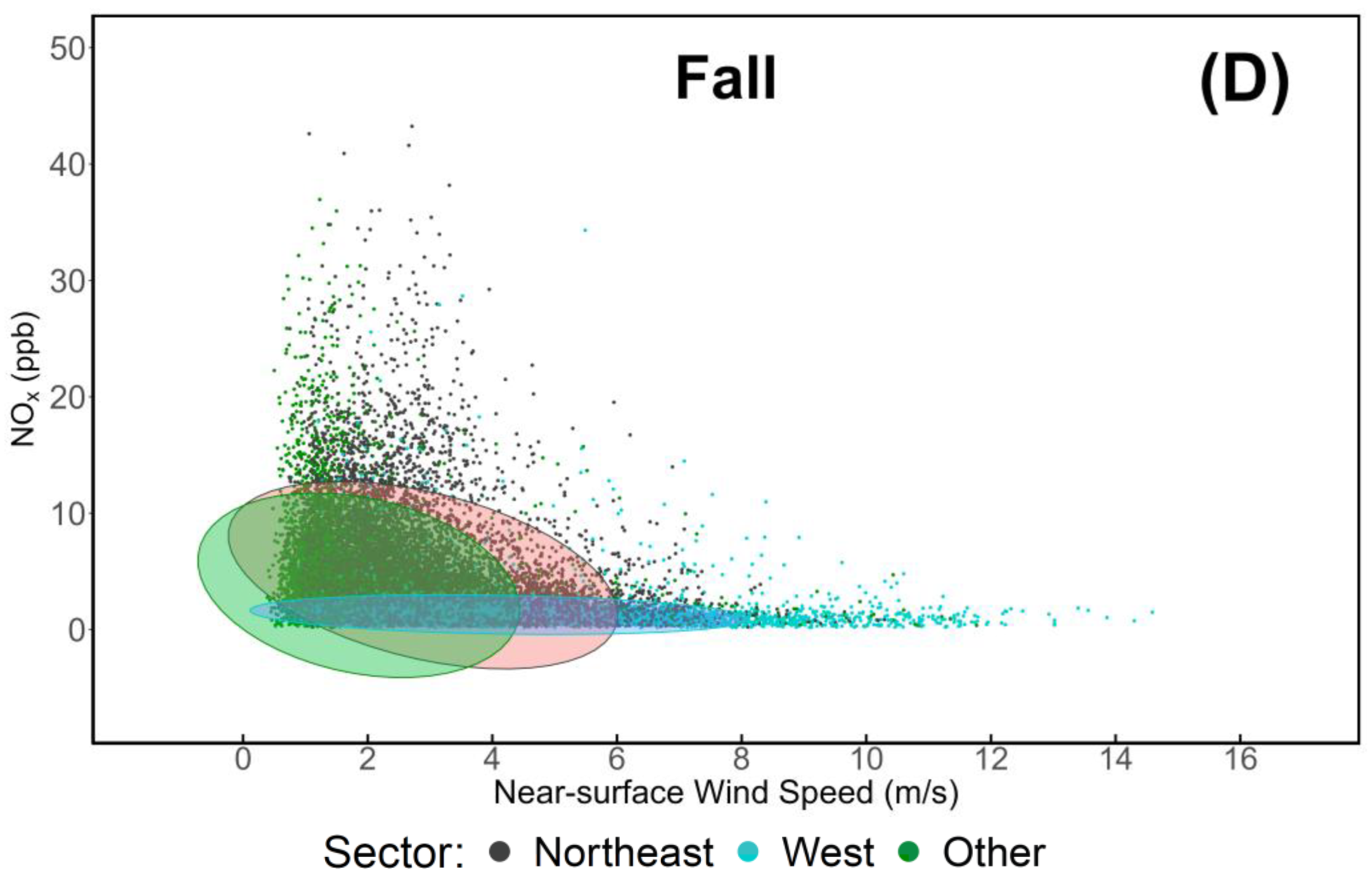

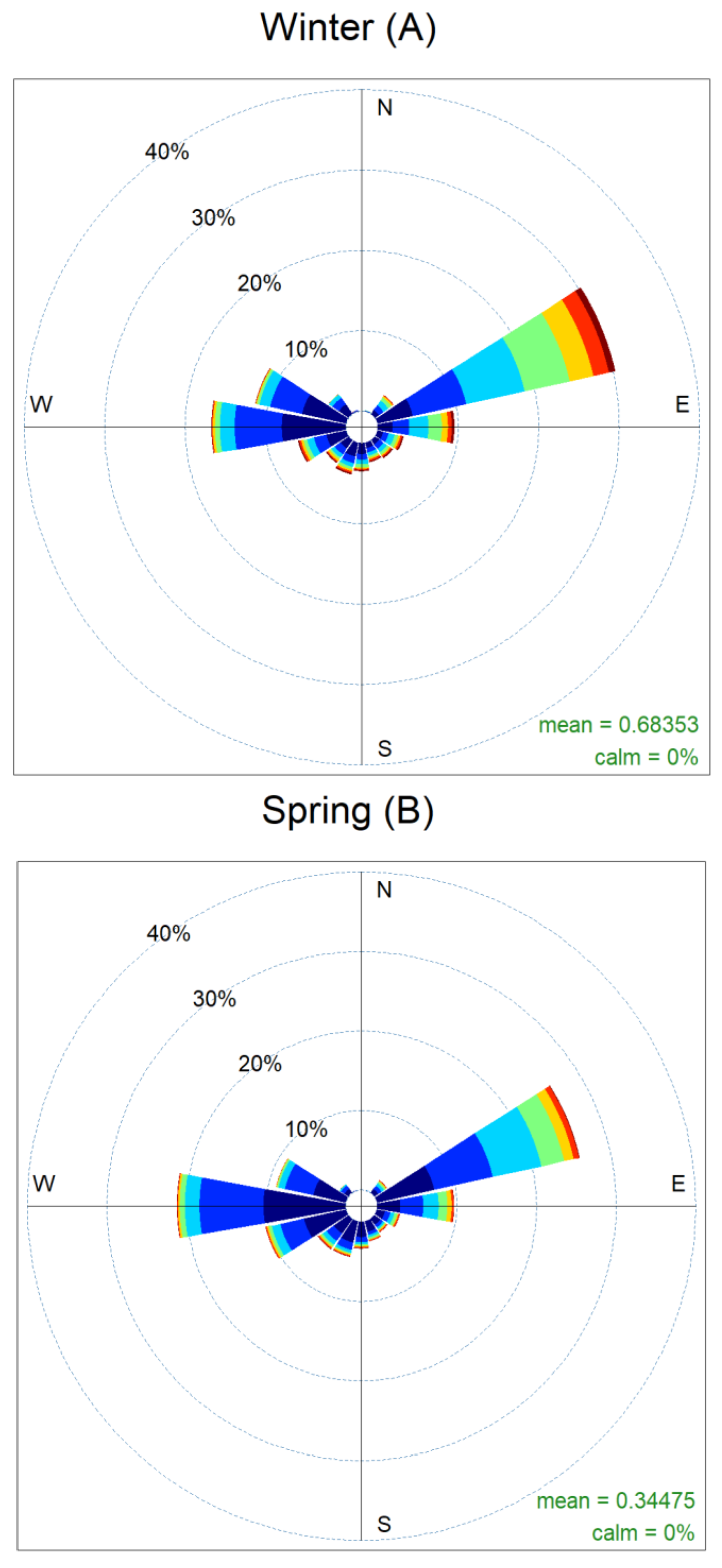

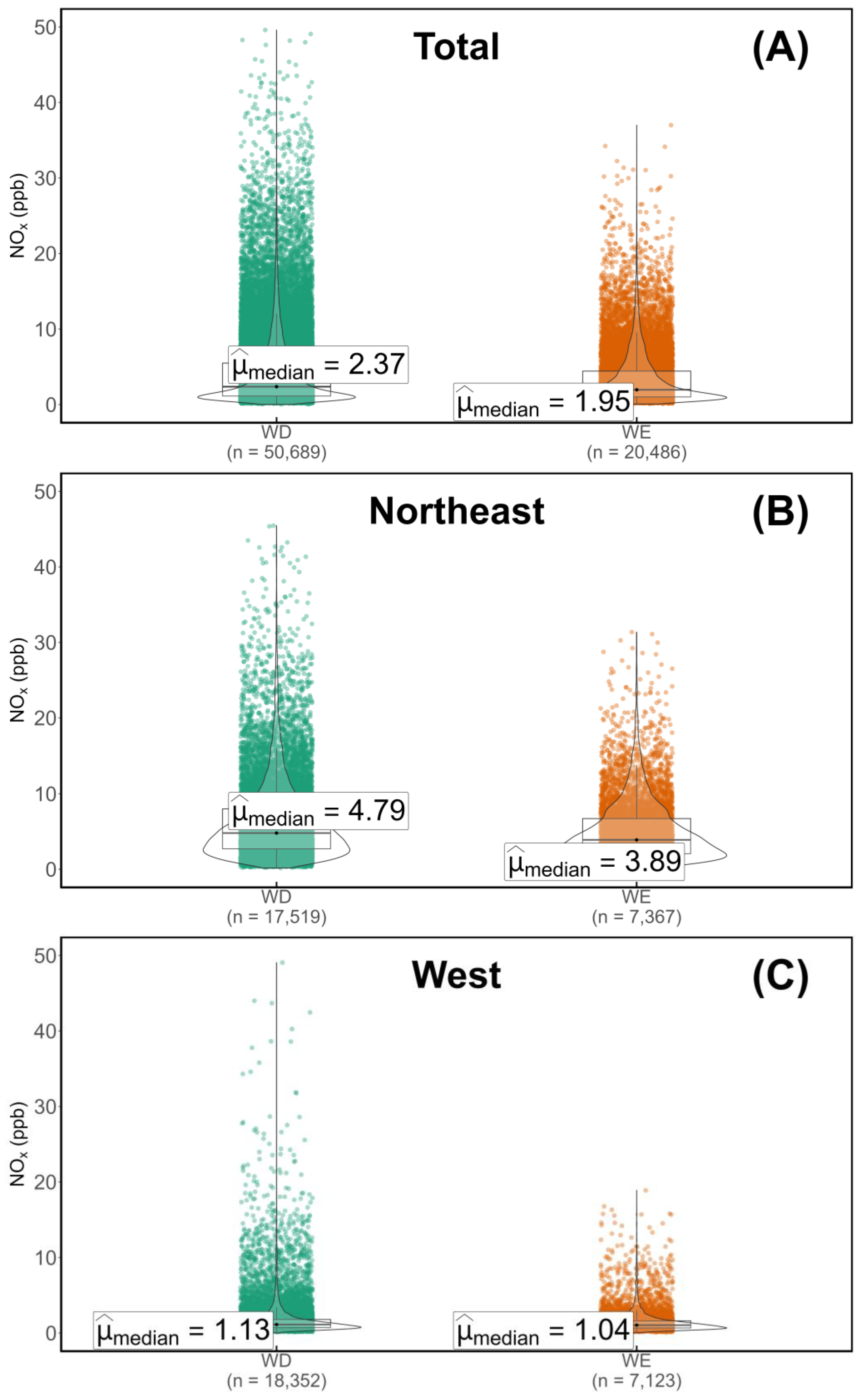

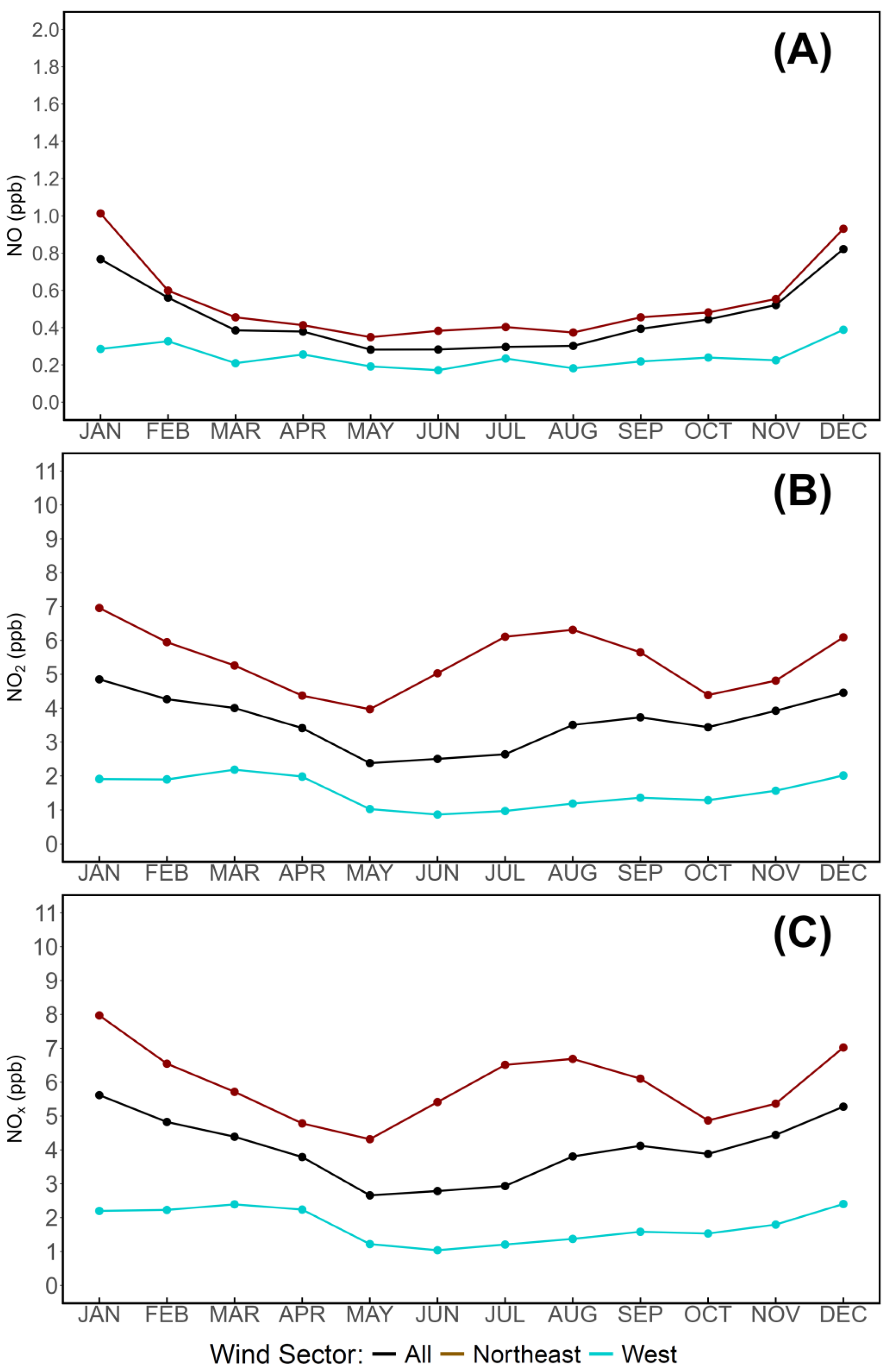

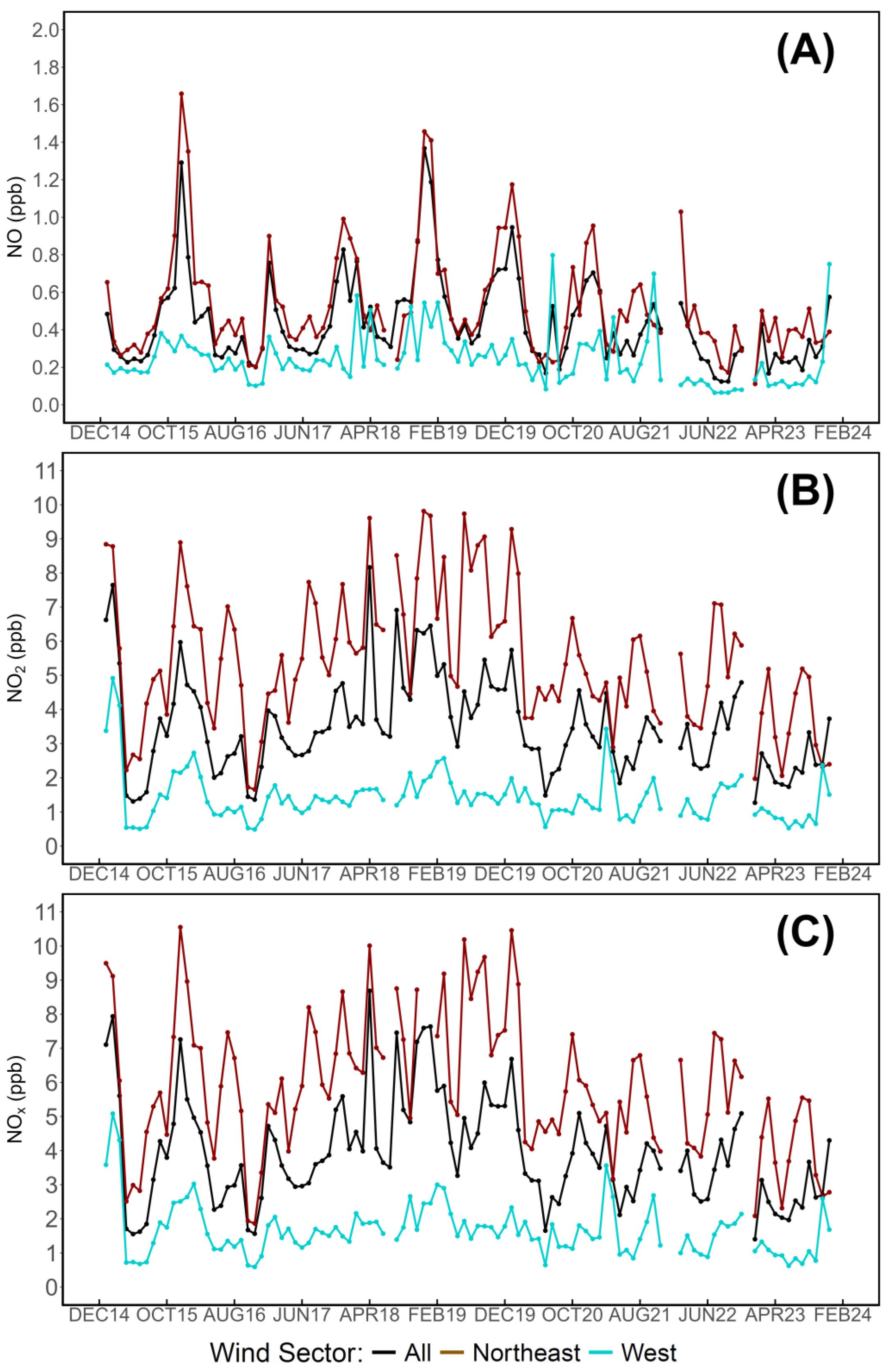

The World Meteorological Organization / Global Atmosphere Watch (WMO/GAW) observation site of Lamezia Terme (code: LMT) in Calabria, Italy has been measuring nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) (together referred to as NOx) for a decade, however only a limited number of studies have evaluated their variability at the site, accounting for short measurement periods. In this work, nine continuous years (2015-2023) of measurements are analyzed to assess daily, weekly, seasonal and multi-year tendencies, also accounting for local wind circulation, which is known to have a relevant impact on LMT’s measurements due to the station’s coastal characteristics in the context of the central Mediterranean Basin. For the first time, a multi-year evaluation on LMT data also considers the local vertical wind profile record to integrate conventional measurements with additional information on air mass transport at low altitudes. The analysis showed peaks in early morning NOx concentrations attributable to rush hour traffic, while in the evening NO2 peaks are present with minor NO counterparts. Weekly cycles have yielded the most statistically significant results of any other similar evaluation at the sites, with all combinations of parameters, seasons, and wind corridors indicating tangible differences between weekday (Monday to Friday) and weekend (Saturday and Sunday) concentrations. The analysis of multi-year variability has shown a slightly declining tendency, however sporadic bursts in concentrations limit the statistical significance of downward trends.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Observation Site and Employed Methodologies

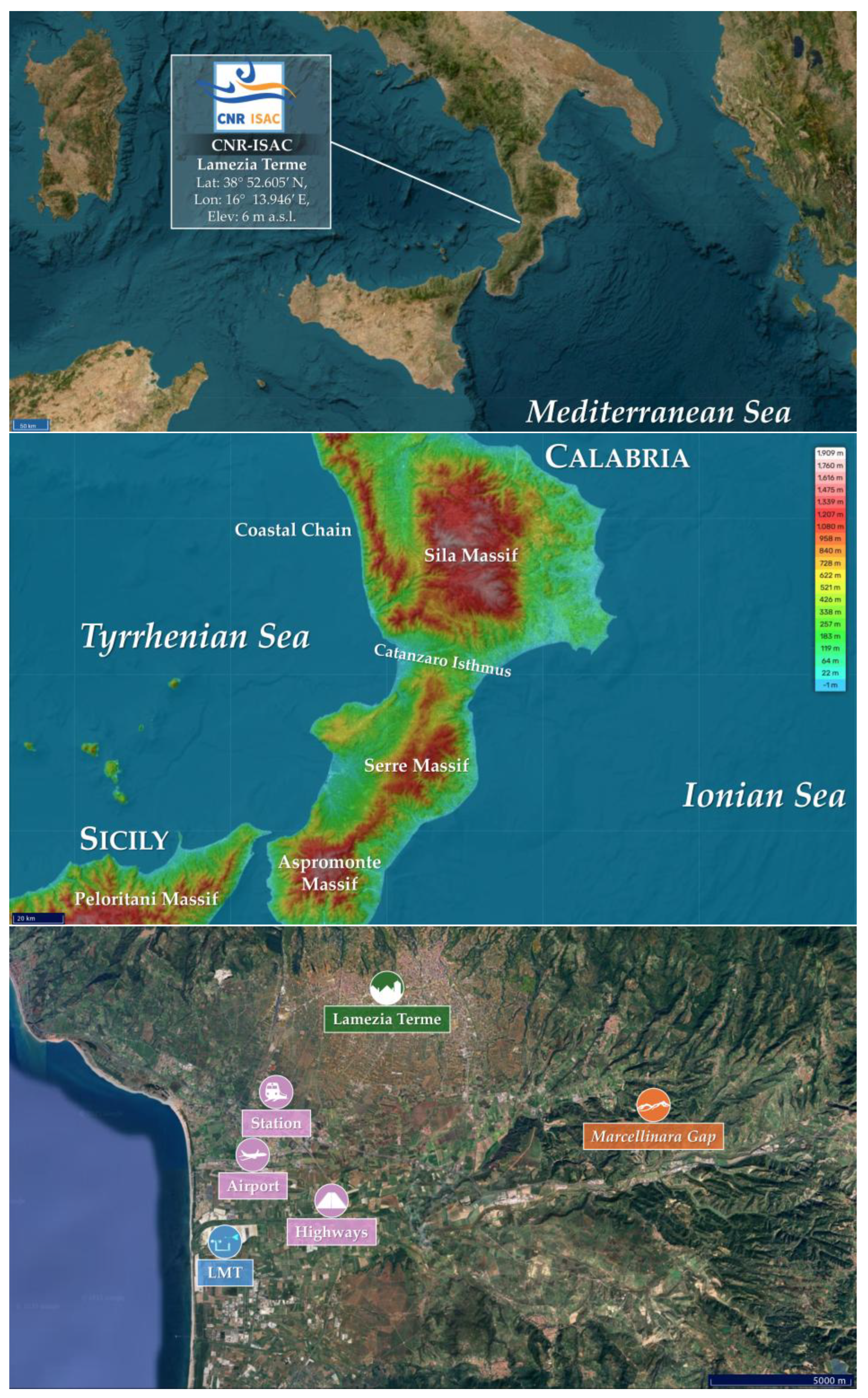

2.1. Characteristics of the LMT Regional Site in Calabria, Italy

2.2. Instruments, Data and Methodologies

| Year | Hours | Thermo 42i | Vaisala WXT520 | ZephIR 300 | NMTO | NLID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 8760 | 92.73% | 95.90% | 66.32% | 91.01% | 61.96% |

| 2016 | 8784 | 95.91% | 96.34% | 92.36% | 93.23% | 89.92% |

| 2017 | 8760 | 96.39% | 93.80% | 97.67% | 91.75% | 95.95% |

| 2018 | 8760 | 98.11% | 77.05% | 91.89% | 75.67% | 91.01% |

| 2019 | 8760 | 96.78% | 98.59% | 29.48% | 96.75% | 28.07% |

| 2020 | 8784 | 94.23% | 99.98% | - | 94.22% | - |

| 2021 | 8760 | 87.14% | 99.74% | 40.70% | 87.13% | 38.50% |

| 2022 | 8760 | 69% | 90.11% | 88.89% | 67.59% | 68.97% |

| 2023 | 8760 | 81.86% | 96.3% | 96.43% | 80.43% | 79.08% |

| 788881 | 90.24%2 | 94.20%2 | 67.08%2 | 86.42%2 | 61.49%2 |

3. Results

3.1. Variability and General Trends During the Observed Period

3.2. Analysis and Evaluation of NOx Daily Cycles

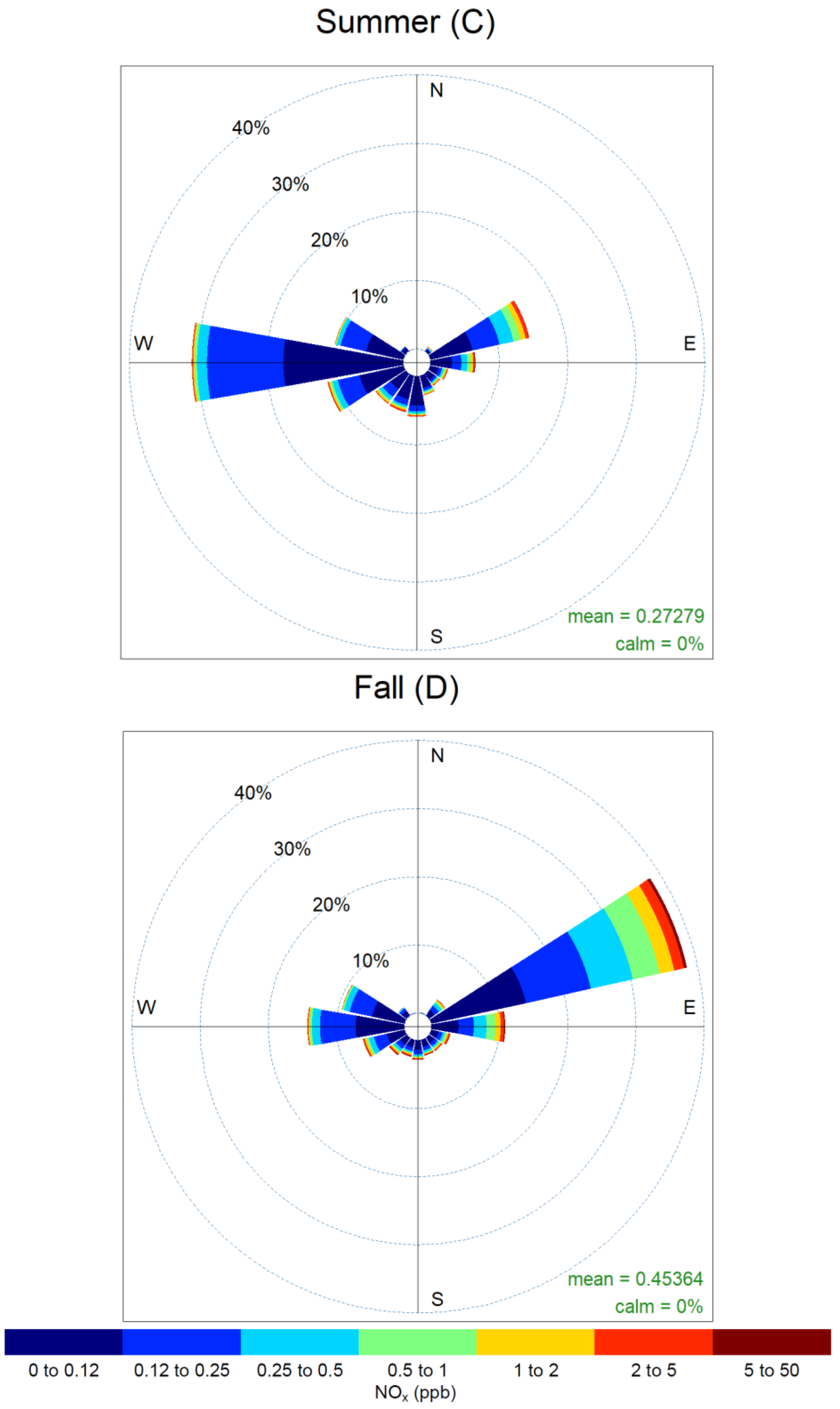

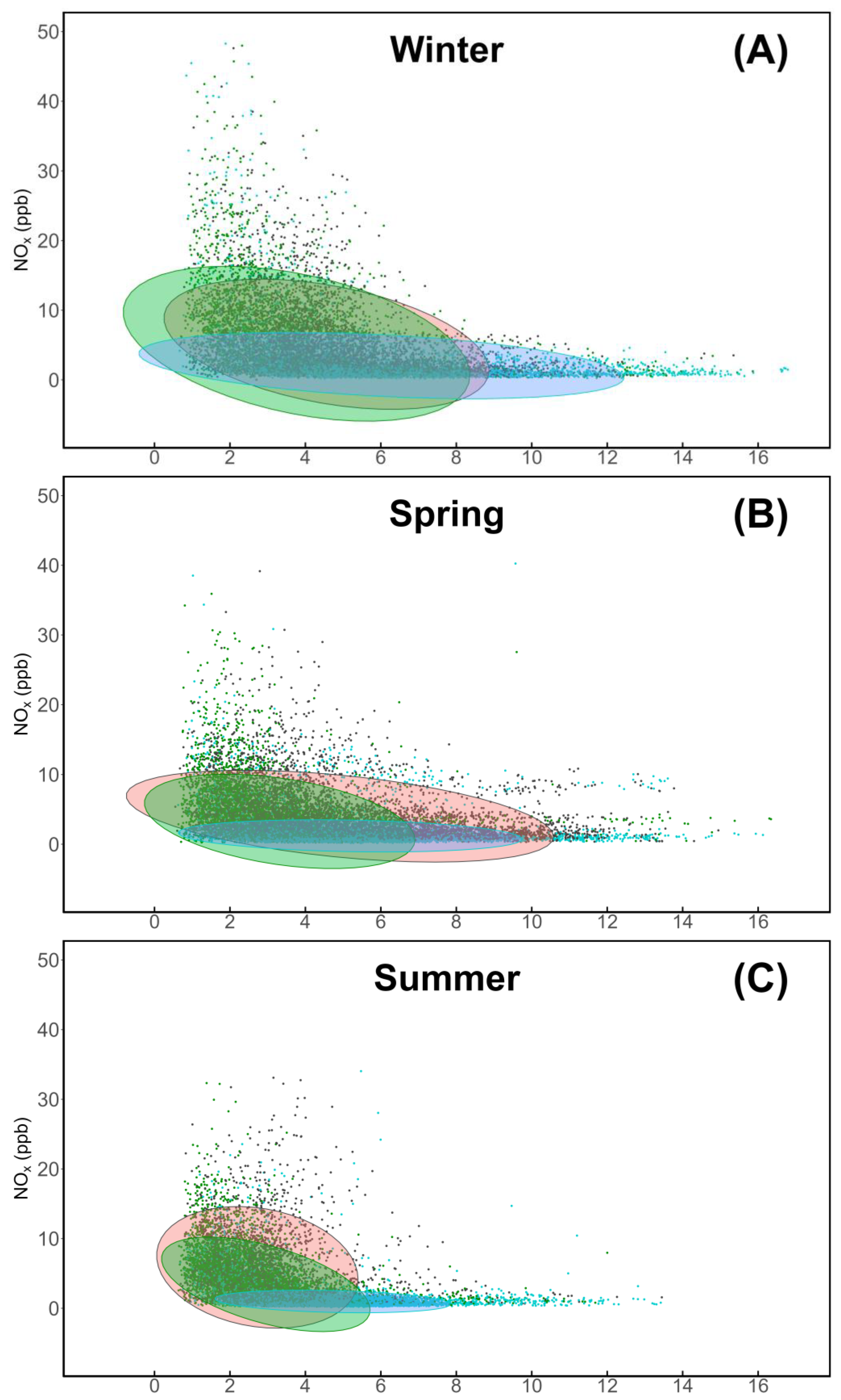

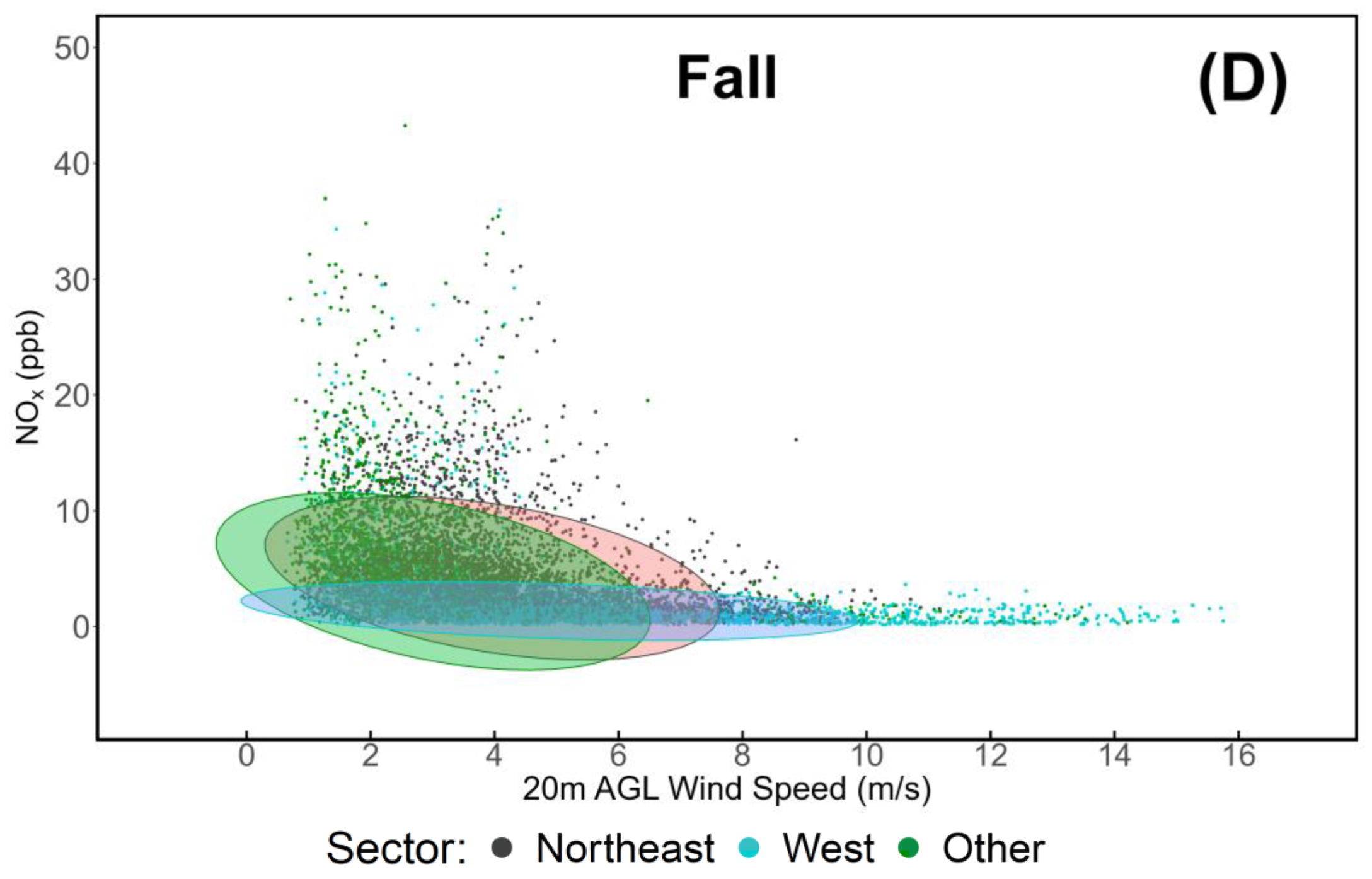

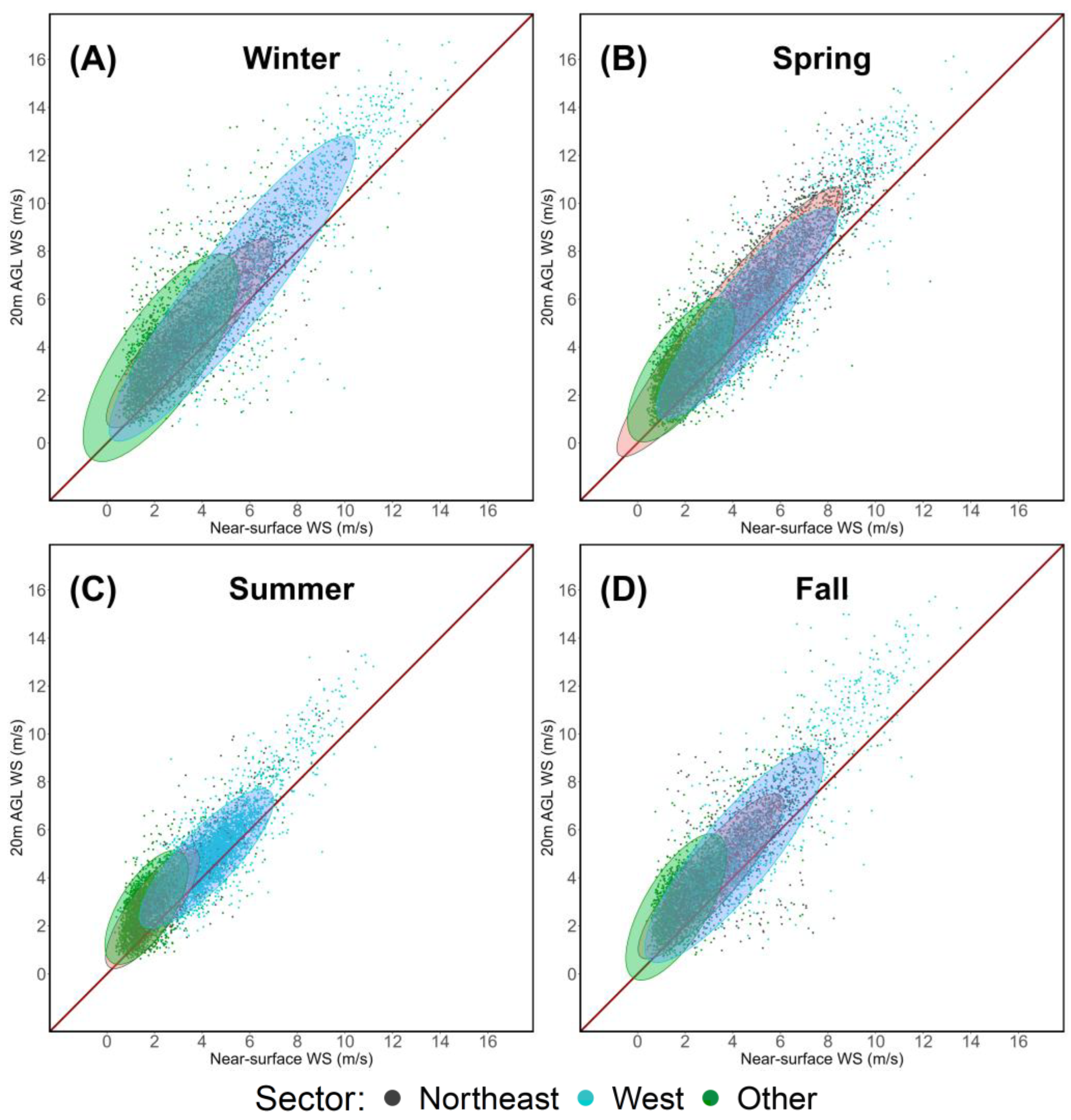

3.3. Variability with Near-Surface Wind Speed/Direction

3.4. Variability with 20m AGL Wind Speed/Direction

3.5. Weekly Analysis

3.6. Annual Cycles and Multi-Year Tendencies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Navarro-González, R.; McKay, C.P.; Mvondo, D.N. A possible nitrogen crisis for Archaean life due to reduced nitrogen fixation by lightning. Nature 2001, 412, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, J.; Zerkle, A.L.; Bekker, A. Geologic and geochemical constraints on Earth’s early atmosphere. Treat. Geochem. 2014, 6, 91–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerhayes, C.P. Paleoclimatology: from snowball Earth to the Anthropocene. Wiley, 2020.

- Ball, J.C.; Hurley, M.D.; Straccia, A.M.; Gierczak, C.A. Thermal release of nitric oxide from ambient air and diesel particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzblau, E.; Popp, C.J. Nitrogen oxides produced from lightning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1989, 94, 11089–11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, M.S.; Harrison, J.T.H.; Anastasi, C. Formation of nitrogen oxides by electrical discharges and implications for atmospheric lightning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1996, 101, 6963–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, D.Z.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Plantevin, P.-H.; Carver, G.D.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Law, K.S.; Pyle, J.A.; Shallcross, D.E.; Wang, K.-Y. Modelling NOx from lightning and its impact on global chemical fields. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 4477–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, X.; Zhang, R.; Brasseur, G.; Lei, W. Global NOx Production by Lightning. J. Atmos. Chem. 2002, 43, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Soula, S.; Pont, V.; Qie, X. NOx ground concentration at a station at high altitude in relation to cloud-to-ground lightning flashes. Atmos. Res. 2005, 75, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Laughner, J.L.; Cohen, R.C. Lightning NO2 simulation over the contiguous US and its effects on satellite NO2 retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 13067–13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudman, R.C.; Jacob, D.J.; Turquety, S.; Leibensperger, E.M.; Murray, L.T.; Wu, S.; Gilliland, A.B.; Avery, M.; Bertram, T.H.; Brune, W.; et al. Surface and lightning sources of nitrogen oxides over the United States: Magnitudes, chemical evolution, and outflow. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D12S05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, U.; Huntrieser, H. The global lightning-induced nitrogen oxides source. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 3823–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, T.; Wu, D.; Chen, L.; He, G.; Yang, H.; Zou, Y.; Pei, C.; Yue, D.; Tao, L.; Ouyang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. The influence of lightning activity on NOx and O3 in the Pearl River Delta region. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, X.; Deng, J.; Chen, K.; Wang, Q.; He, M. Impact of lightning-induced nitrogen oxides over and around the Tibetan Plateau ozone valley. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD039575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaylou, M.; Pegahfar, N.; Alizadeh, O. The impact of lightning NOx production on ground-level ozone in Tehran. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2023EA003372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasek, J.A.; Lajnert, R. On the Issues of NOx as Greenhouse Gases: An Ongoing Discussion…. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J. Lifetimes and Eigenstates in Atmospheric Chemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwent, R.G.; Collins, W.J.; Johnson, C.E.; Stevenson, D.S. Transient Behaviour of Tropospheric Ozone Precursors in a Global 3-D CTM and Their Indirect Greenhouse Effects. Clim. Change 2001, 49, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.S.; Young, P.J.; Naik, V.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Shindell, D.T.; Voulgarakis, A.; Skeie, R.B.; Dalsoren, S.B.; Myhre, G.; Berntsen, T.K.; et al. Tropospheric ozone changes, radiative forcing and attribution to emissions in the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 3063–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, P.S. Gas-phase radical chemistry in the troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollner, A.K.; Valluvadasan, S.; Feng, L.; Sprague, M.K.; Okumura, M.; Milligan, D.B.; Bloss, W.J.; Sander, S.P.; Martien, P.T.; Harley, R.A.; McCoy, A.B.; Carter, W.P.L. Rate of gas phase association of hydroxyl radical and nitrogen dioxide. Science 2010, 330, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Gao, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y. Influence of atmospheric oxidation capacity on atmospheric particulate matters concentration in Lanzhou. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penner, J.E.; Atherton, C.S.; Dignon, J.; Ghan, S.J.; Walton, J.J.; Hameed, S. Tropospheric nitrogen—A 3-dimensional study of sources, distributions, and deposition. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1991, 96, 959–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M.; Parrish, D.D.; Buhr, M.P.; Norton, R.B.; Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Anlauf, K.G.; Bottenheim, J.W.; Tang, Y.Z.; Wiebe, H.A.; Roberts, J.M.; et al. Correlation of ozone with NOy in photochemically aged air. J. Geophys. Res.—Atmos. 1993, 98, 2917–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J.; Heikes, E.G.; Fan, S.-M.; Logan, J.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Singh, H.B.; Gregory, G.L.; Talbot, R.W.; Blake, D.R.; et al. Origin of ozone and NOx in the tropical troposphere: A photochemical analysis of aircraft observations over the South Atlantic basin. J. Geophys. Res.—Atmos. 1996, 101, 24235–24250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauglustaine, D.A.; Emmons, L.K.; Newchurch, M.; Brasseur, G.P.; Takao, T.; Matsubara, K.; Johnson, J.; Ridley, B.; Stith, J.; Dye, J. On the role of lightning NOx in the formation of tropospheric ozone plumes: A global model perspective. J. Atmos. Chem. 2001, 38, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, S.; Dommen, J.; Neininger, B.; Reimann, S.; Staehelin, J.; Prévôt, A.S.H. Influence of mountain venting in the Alps on the ozone chemistry of the lower free troposphere and the European pollution export. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Mantilla, E.; Millán, M.M. Using measured and modeled indicators to assess ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivity in a western Mediterranean coastal environment. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 7167–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Moller, S.J.; Read, K.A.; Lewis, A.C.; Mendes, L.; Carpenter, L.J. Year-round measurements of nitrogen oxides and ozone in the tropical North Atlantic marine boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroidis, I.; Chaloulakou, A. Long-term trends of primary and secondary NO2 production in the Athens area. Variation of the NO2/NOx ratio. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6872–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.D.; Allen, D.T.; Bates, T.S.; Estes, M.; Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Feingold, G.; Ferrare, R.; Hardesty, R.M.; Meagher, J.F.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W.; et al. Overview of the Second Texas Air Quality Study (TexAQS II) and the Gulf of Mexico Atmospheric Composition and Climate Study (GoMACCS). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D00F13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.T.; Allan, J.D.; Bower, K.N.; Highwood, E.J.; Liu, D.; McMeeking, G.R.; Northway, M.J.; Williams, P.I.; Krejci, R.; Coe, H. Airborne measurements of the spatial distribution of aerosol chemical composition across Europe and evolution of the organic fraction. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 4065–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Lo Feudo, T.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Investigation of Carbon Monoxide, Carbon Dioxide, and Methane Source Variability at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy) Using the Ratio of Ozone to Nitrogen Oxides as a Proximity Indicator. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenger, J. Urban air quality. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 4877–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J. Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999.

- Colvile, R.N.; Hutchinson, E.J.; Mindell, J.S.; Warren, R.F. The transport sector as a source of air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 1537–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics; A Wiley-Inter Science Publication, John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006.

- Beevers, S.D.; Westmoreland, E.; de Jong, M.C.; Williams, M.L.; Carslaw, D.C. Trends in NOx and NO2 emissions from road traffic in Great Britain. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 54, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Beirle, S.; Zhang, Q.; Dörner, S.; He, K.; Wagner, T. NOx lifetimes and emissions of cities and power plants in polluted background estimated by satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 5283–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.Y.H.; Law, A. A study of personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide using passive samplers. Build. Environ. 2000, 35, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıca, S.N.; Özden Üzmez, Ö.; Malkoç, S. Household Indoor Concentration Levels of Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) and Ozone (O3) in Eskisehir, Turkey. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.; Sofia, D.; Faggiano, A.; Bergomi, A.; Comite, V.; Guglielmi, V.; Fermo, P.; Proto, A.; Motta, O. Assessment of some air pollutants in the Sanctuary of the Beata Vergine dei Miracoli (Saronno, Italy) and first evaluation of a new axial passive sampler for nitrogen dioxide. Microchem. J. 2024, 201, 110593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, R.R. Measurements of reactive nitrogen compounds in the free troposphere. Atmos. Environ. 1984, 18, 2585–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehhalt, D.H.; Rohrer, F.; Wahner, A. Sources and distribution of NOx in the upper troposphere at northern mid-latitudes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1992, 97, 3725–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeglé, L.; Jacob, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Weinheimer, A.J.; Ridley, B.A.; Campos, T.L.; Sachse, G.W.; Hagen, D.E. Sources and chemistry of NOx in the upper troposphere over the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 1705–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H.; Moxim, W.J.; Klonecki, A.A.; Kasibhatla, P.S. Simulated tropospheric NOx: Its evaluation, global distribution and individual source contributions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 26279–26306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish, S.E.; He, H.; Ren, X.; Roberts, S.J.; Salawitch, R.J.; Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Shao, M.; Lu, S.; Dickerson, R.R. Measurement report: Aircraft observations of ozone, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds over Hebei Province, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 14523–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Jacob, D.J.; Dang, R.; Lamsal, L.N.; Strode, S.A.; Steenrod, S.D.; Boersma, K.F.; Eastham, S.D.; Fritz, T.M.; Thompson, C.; et al. Nitrogen oxides in the free troposphere: implications for tropospheric oxidants and the interpretation of satellite NO2 measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1227–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y.; Hong, H.; Fu, W.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Tropospheric NO2 Column over Tibet Plateau According to Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer: Spatial, Seasonal, and Diurnal Variations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, J.; Chaulya, S.K.; Oruganti, S.S. Probabilistic health risk assessment of industrial workers exposed to air pollution. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2000, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J. L, Haeuber, R.; Garcia, V.; Russell, A.G.; Neas, L. Impact of nitrogen and climate change interactions on ambient air pollution and human health. Biogeochemistry 2013, 114, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, H.; Mayeres, I.M.; Panis, L.I.; De Nocker, L.; Deutsch, F.; Lefebvre, W. PM2.5 and NOx from traffic: Human health impacts, external costs and policy implications from the Belgian perspective. Transp. Res. D: Transp. Environ. 2012, 17, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zelm, R.; Preiss, P.; van Goethem, T.; Van Dingenen, R.; Huijbregts, M. Regionalized life cycle impact assessment of air pollution on the global scale: Damage to human health and vegetation. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 134, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wu, H.; Chiu, Y.-H. The Dynamic Analysis of the Pollutant Emissions Impact on Human Health in China Industries Based on the Meta-Frontier DEA. Healthcare 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, A.B.; Bossy-Wetzel, E. Impact of nitric oxide on metabolism in health and age-related disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Alrashed, A.H.; Almana, A.A.; Altheiban, Y.I.; Aldosari, M.S.; Almudarra, N.F.; Alwabel, S.A. Lung function and fractional exhaled nitric oxide among petroleum refinery workers. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2015, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yang, W.; Jiang, L.; Lyu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Gao, B.; Li, X. Association of short-term exposure to ambient air pollutants with exhaled nitric oxide in hospitalized patients with respiratory-system diseases. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 168, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Aldeghaither, M.; Alnaeem, K.A.; Alabdullatif, F.S.; Alzamil, A.F.; Alshunaifi, A.I.; Alfayez, A.S.; Almahmoud, M.; Meo, A.S.; El-Mubarak, A.H. Effect of motor vehicle pollution on lung function, fractional exhaled nitric oxide and cognitive function among school adolescents. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 8678–8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czubaj-Kowal, M.; Kurzawa, R.; Mazurek, H.; Sokołowski, M.; Friediger, T.; Polak, M.; Nowicki, G.J. Relationship Between Air Pollution and the Concentration of Nitric Oxide in the Exhaled Air (FeNO) in 8–9-Year-Old School Children in Krakow. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruwali, S.; Talebi, S.; Fernando, A.; Wijeratne, L.O.H.; Waczak, J.; Dewage, P.M.H.; Lary, D.J.; Sadler, J.; Lary, T.; Lary, M.; et al. Quantifying Inhaled Concentrations of Particulate Matter, Carbon Dioxide, Nitrogen Dioxide, and Nitric Oxide Using Observed Biometric Responses with Machine Learning. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 1019–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, R.J.; Clelland, R.C.; Boyce, D.E.; Bowers, E.J. Atmospheric sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and lead as mutagenic hazards to human health. Mutation Res. 1974, 26, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Pilotto, L.S.; Douglas, R.M.; Attewell, R.G.; Wilson, S.R. Respiratory effects associated with indoor nitrogen dioxide exposure in children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoli, E. Short-term effects of nitrogen dioxide on mortality: An analysis within the APHEA project. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breysse, P.N.; Diette, G.B.; Matsui, E.C.; Butz, A.M.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C. Indoor air pollution and asthma in children. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.W.; Butland, B.K.; Anderson, H.R.; Maynard, R.L. Long-term Concentrations of Nitrogen Dioxide and Mortality: A Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Epidemiology 2018, 29, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Zeng, D.; Zeng, H. Effects of nitrogen dioxide exposure on the risk of eye and adnexa diseases among children in Shenzhen, China: an assessment using the generalized additive modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 32, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Qian, Y.; Steenland, K.; Caudle, W.M.; Liu, Y.; Sarnat, J.; Papatheodorou, S.; Shi, L. Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou, A.; Praud, D.; Coudon, T.; Deygas, F.; Grassot, L.; Dubuis, M.; Faure, E.; Couvidat, F.; Caudeville, J.; Bessagnet, B.; et al. Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide air pollution and breast cancer risk: A nested case-control within the French E3N cohort study. Environ. Poll. 2023, 317, 120719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.-A.; Pescariu, S.-A.; Zus, A.-S.; Gaiţă, D.; Mornoş, C. Impact of Short-Term Exposure to Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) and Ozone (O3) on Hospital Admissions for Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Toxics 2024, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valin, L.C.; Russell, A.R.; Hudman, R.C.; Cohen, R.C. 2011 Effects of model resolution on the interpretation of satellite NO2 observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 11647–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Streets, D.G. Increase in NOx Emissions from Indian Thermal Power Plants during 1996–2010: Unit-Based Inventories and Multisatellite Observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7463–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.N.; Yoshida, Y.; de Foy, B.; Lamsal, L.N.; Streets, D.G.; Lu, Z.; Pickering, K.E.; Krotkov, N. A. The observed response of Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) NO2 columns to NOx emission controls on power plants in the United States: 2005–2011. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 81, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Wang, Y.; Yin, R.; Zhang, Y.; Smeltzer, C. Inverse modelling of NOx emissions over eastern China: uncertainties due to chemical non-linearity. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2016, 9, 5193–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Martin, R.V.; Padmanabhan, A.; Henze, D.K. Comparing mass balance and adjoint methods for inverse modeling of nitrogen dioxide columns for global nitrogen oxide emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 4718–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughner, J.L.; Cohen, R.C. Direct observation of changing NOx lifetime in North American cities. Science 2019, 366, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Jacob, D.J.; Li, K.; Silvern, R.F.; Zhai, S.; Liu, M.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Q. Effect of changing NOx lifetime on the seasonality and long-term trends of satellite-observed tropospheric NO2 columns over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K.; Richter, A.; Burrows, J.P. Variability of nitrogen oxide emission fluxes and lifetimes estimated from Sentinel-5P TROPOMI observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 2745–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.F.; Mahmud, M.S. Review on Detection Methods of Nitrogen Species in Air, Soil and Water. Nitrogen 2022, 3, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillas, C.; Álvarez, S.; Pires, J.C.M.; García, A.J.; Martínez, S. Linking Satellite and Ground Observations of NO2 in Spanish Cities: Influence of Meteorology and O3. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Calzolari, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Dinoi, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Sferlazzo, D.; Di Iorio, T.; Piacentino, S.; Marinoni, A.; Maione, M.; Bonasoni, P. Investigation of reactive gases and methane variability in the coastal boundary layer of the central Mediterranean basin. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Trends in CO, CO2, CH4, BC, and NOx during the first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown: source insights from the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Sustainability 2024, 16, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, S.G. The record of tidal cycles in mixed silici–bioclastic deposits: Examples from small Plio–Pleistocene peripheral basins of the microtidal Central Mediterranean Sea. Sedimentology 2010, 58, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, D.; Longhitano, S.G.; Muto, F. Sedimentary features of the lower Pleistocene mixed siliciclastic-bioclastic tidal deposits of the Catanzaro Strait (Calabrian Arc, south Italy). Rend. Online Della Soc. Geol. Ital. 2012, 21, 919–920. [Google Scholar]

- Longhitano, S.G. A facies-based depositional model for ancient and modern, tectonically-confined tidal straits. Terra Nova 2013, 25, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, S.G.; Chiarella, D.; Muto, F. Three-dimensional to two-dimensional cross-strata transition in the lower Pleistocene Catanzaro tidal strait transgressive succession (southern Italy). Sedimentology 2014, 61, 2136–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, D.; Moretti, M.; Longhitano, S.G.; Muto, F. Deformed cross-stratified deposits in the Early Pleistocene tidally-dominated Catanzaro strait-fill succession, Calabrian Arc (Southern Italy): Triggering mechanisms and environmental significance. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 344, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, G.E.; Cluff, L.S.; Taylor, C.L. Seismicity and uplift of southern Italy. Tectonophysics 1975, 29, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, T.; Dai Pra, G.; Sylos Labini, S. Geochronology of Pleistocene marine terraces and regional tectonics in Tyrrhenian coast of South Calabria, Italy. Il Quaternario 1994, 7, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, C.; Bianca, M.; Catalano, S.; De Guidi, G.; Gresta, S.; Langher, H.; Tortorici, L. The geological map of the urban area of Catania (Sicily): Morphotectonic and seismotectonic implications. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2001, 5, 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Purcell, A.; Silenzi, S. Sea-level change along the Italian coast for the past 10,000 yr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 1567–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda-Boluda, D.C.; Whittaker, A.C. Structural and geomorphological constraints on active normal faulting and landscape evolution in Calabria, Italy. J. Geol. Soc. 2017, 174, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzoli, P.A.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Saliège, J.F.; Sansò, P. Late Holocene emergence in Calabria, Italy. Mar. Geol. 1997, 141, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruello, M.R.; Cinque, A.; Di Donato, V.; Molisso, F.; Terrasi, F.; Russo Ermolli, E. Interplay between sea level rise and tectonics in the Holocene evolution of the St. Eufemia Plain (Calabria, Italy). J. Coast. Conserv. 2017, 21, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogniben, L. Schema introduttivo alla geologia del confine Calabro-lucano (Introductory scheme to the geology of the Calabrian-Lucanian boundary. Mem. Soc. Geol. It. 1969, 8, 453–763. [Google Scholar]

- Amodio-Morelli, L.; Bonardi, G.; Colonna, V.; Dietrich, D.; Giunta, G.; Ippolito, F.; Liguori, V.; Lorenzoni, P.; Paglionico, A.; Perrone, V.; et al. L’Arco Calabro-Peloritano nell’orogene Appenninico-Maghrebide. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1976, 17, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi, G.; De Capoa, P.; Fioretti, B.; Perrone, V. Some remarks on the Calabria-Peloritani arc and its relationship with the southern Apennines. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 1994, 36, 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Scandone, P. Structure and evolution of the Calabrian Arc. Earth Evol. Sci. 1982, 3, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, W. A former continuation of the Alps. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1976, 87, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royden, L.; Patacca, E.; Scandone, P. Segmentation and configuration of subducted lithosphere in Italy: An important control on thrust-belt and foredeep-basin evolution. Geology 1987, 15, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinverno, A.; Ryan, W.B.F. Extension in the Tyrrhenian Sea and shortening in the Apennines as result of arc migration driven by sinking of the lithosphere. Tectonics 1986, 5, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critelli, S.; Muto, F.; Tripodi, V.; Perri, F. Relationships between Lithospheric Flexure, Thrust Tectonics and Stratigraphic Sequences in Foreland Setting: The Southern Apennines Foreland Basin System, Italy. In Tectonics 2; Schattner, U., Ed.; Intech Open Access Publisher: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 121–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffaro, M.; Petricca, P.; Conti, A.; Palano, M.; Billi, A.; Bigi, S. Fault kinematic modeling along a widely deformed plate boundary in Southern Italy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, I.; Speranza, F.; Chiappini, M. Ultrafast oceanic spreading of the Marsili Basin, southern Tyrrhenian Sea: Evidence from magnetic anomaly analysis. Geology 2006, 34, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchi, L.; Caratori Tontini, F.; Muccini, F.; Marani, M.P.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Carmisciano, C. Chronology of the transition from a spreading ridge to an accretional seamount in the Marsili backarc basin (Tyrrhenian Sea). Terra Nova 2009, 21, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, J.P.; Scheepers, P.J.J. Neotectonic rotations in the Calabrian Arc; implications for a Pliocene-Recent geodynamic scenario for the Central Mediterranean. Earth Sci. Rev. 1995, 39, 207–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, I.P.; Sagri, M.; Colella, A. Neogene—Quaternary basins of the inner Apennines and Calabrian arc. In Anatomy of an Orogen. The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins; Vai, G.B., Martini, I.P., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifelli, F.; Mattei, M.; Rossetti, F. Tectonic evolution of arcuate mountain belts on top of a retreating subduction slab: The example of the Calabrian Arc. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2007, 112, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansi, C.; Muto, F.; Critelli, S.; Iovine, G. Neogene-Quaternary strike-slip tectonics in the central Calabrian Arc (southern Italy). J. Geodyn. 2007, 43, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, P.; Bosi, V. Paleoseismology along the Cittanova fault: Implications for seismotectonics and earthquake recurrence in Calabria (southern Italy). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2002, 107, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansi, C.; Folino Gallo, M.; Muto, F.; Perrotta, P.; Russo, L.; Critelli, S. Seismotectonics and landslides of the Crati Graben (Calabrian Arc, Southern Italy). J. Maps 2016, 12 (Suppl. S1), 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, C.; Barberi, G.; Barreca, G.; Brighenti, F.; Carnemolla, F.; De Guidi, G.; Monaco, C.; Pepe, F.; Scarfì, L. Recent Activity and Kinematics of the Bounding Faults of the Catanzaro Trough (Central Calabria, Italy): New Morphotectonic, Geodetic and Seismological Data. Geosciences 2021, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.; Tortorici, L. Active faulting in the Calabrian arc and eastern Sicily. J. Geodyn. 2000, 29, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, C.; Parrino, N.; Pepe, F.; Tansi, C.; Monaco, C. Geomorphological and Morphometric Analyses of the Catanzaro Trough (Central Calabrian Arc, Southern Italy): Seismotectonic Implications. Geosciences 2022, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, F. Evoluzione neotettonica dei principali sistemi di faglie della Calabria centrale. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1979, 98, 387–430. [Google Scholar]

- Langone, A.; Gueguen, E.; Prosser, G.; Caggianelli, A.; Rottura, A. The Curinga-Girifalco fault zone (northern Serre, Calabria) and its significance within the Alpine tectonic evolution of the western Mediterranean. J. Geodyn. 2006, 42, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, A.; Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Lolli, B.; Gasperini, P. The Italian earthquake catalogue CPTI15. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 18, 2953–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, A.; Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Lolli, B.; Gasperini, P.; Antonucci, A. Catalogo Parametrico dei Terremoti Italiani (CPTI15), versione 4.0. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). Available online: Rovida, A.; Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Lolli, B.; Gasperini, P.; Antonucci, A. Catalogo Parametrico dei Terremoti Italiani (CPTI15), versione 4.0. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). Available online: https://emidius.mi.ingv.it/CPTI15-DBMI15_v3.0 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; De Leo, L.; Bellecci, C. A study of the breeze circulation during summer and fall 2008 in Calabria, Italy. Atmos. Res. 2010, 97, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; Sempreviva, A.M.; De Leo, L.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Bellecci, C. The seasonal characteristics of the breeze circulation at a coastal Mediterranean site in South Italy. Adv. Sci. Res. 2010, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calidonna, C.R.; Dutta, A.; D’Amico, F.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Lo Feudo, T. Ten-Year Analysis of Mediterranean Coastal Wind Profiles Using Remote Sensing and In Situ Measurements. Wind 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topographic Map. https://en-us.topographic-map.com (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- TessaDEM - Near-global 30-meter Digital Elevation Model (DEM). https://tessadem.com (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Yamazaki, D.; Ikeshima, D.; Tawatari, R.; Yamaguchi, T.; O’Loughlin, F.; Neal, J.C.; Sampson, C.C.; Kanae, S.; Bates, P.D. A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5844–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Methane Cycles and Trends at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Gullì, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Ammoscato, I.; Avolio, E.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; et al. Cyclic and Multi-Year Characterization of Surface Ozone at the WMO/GAW Coastal Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): Implications for Local Environment, Cultural Heritage, and Human Health. Environments 2024, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; De Benedetto, G.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; Dutta, A.; Lo Feudo, T.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Calidonna, C.R. Multimethodological Approach for the Evaluation of Tropospheric Ozone’s Regional Photochemical Pollution at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme, Italy. AppliedChem 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Lo Feudo, T.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Integrated Surface and Tropospheric Column Analysis of Sulfur Dioxide Variability at the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW Regional Station in Calabria, Southern Italy. Environments 2025, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Republic. Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 9 March 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 62. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Italian Republic. Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 18 May 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 127. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/05/18/20A02727/sg (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Sander, S.P.; Golden, D.M.; Kurylo, M.J.; Moortgat, G.K.; Wine, P.H.; Ravishankara, A.R.; Kolb, C.E.; Molina, M.J.; Finlayson-Pitts, B.J.; Orkin, V.L. Chemical Kinetics and Photochemical Data for Use in Atmospheric Studies Evaluation Number 15; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2006.

- Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Benedetto, G.; D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Cristofanelli, P.; De Pino, M.; Gullì, D.; Calidonna, C.R. Methodology for selecting near-surface CH4, CO, and CO2 observations reflecting atmospheric background conditions at the WMO/GAW station in Lamezia Terme, Italy. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, D.A.J.; Wagenaar, J.W. Verification of the ZephIR 300 LiDAR at the ECN LiDAR Calibration Facility for the Offshore Europlatform Measurement Campaign, ECN-M-16-029. Available online: https://resolver.tno.nl/uuid:0e900067-df59-4c76-8f4a-469754ab4d3d (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Knoop, S.; Bosveld, F.C.; de Haij, M.J.; Apituley, A. A 2-year intercomparison of continuous-wave focusing wind lidar and tall mast wind measurements at Cabauw. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 2219–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.4, 2025. https://dplyr.tidyverse.org (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag New York, 2016. ISBN: 978-3-319-24277-4.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarque, C.M.; Bera, A.K. A Test for Normality of Observations and Regression Residuals. Int. Stat. Rev. 1987, 55, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Non-parametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th edition. Charles Griffin, 1975, London.

- Bronaugh, D.; Schoeneberg, A. zyp: Zhang + Yue-Pilon Trends Package, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, D.C.; Ropkins, K. openair --- an R package for air quality data analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 27-28, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friendly, M.; Monette, G.; Fox, J. Elliptical Insights: Understanding Statistical Methods through Elliptical Geometry. Statist. Sci. 2013, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; De Benedetto, G.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; Calidonna, C.R.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; Lo Feudo, T. Tropospheric and Surface Measurements of Combustion Tracers During the 2021 Mediterranean Wildfire Crisis: Insights from the WMO/GAW Site of Lamezia Terme in Calabria, Southern Italy. Gases 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Anthropic-Induced Variability of Greenhouse Gasses and Aerosols at the WMO/GAW Coastal Site of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): Towards a New Method to Assess the Weekly Distribution of Gathered Data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, I. Visualizations with statistical details: The 'ggstatsplot' approach. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, T.; Kim, T.; Yoo, S. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on Growth, Vegetation Indices, and Ammonia Volatilization in Korean Radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Nitrogen 2025, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyan, S.K.; Maithani, D.; Kumar, V. Nitrous Oxide Production and Mitigation Through Nitrification Inhibitors in Agricultural Soils: A Mechanistic Understanding and Comprehensive Evaluation of Influencing Factors. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Sa, Q.; Wang, Y. Effects of Biochar, Biogas Slurry, and Dicyandiamide Application on N2O Emissions from Soil in Tomato Production Under Protected Cultivation. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Calidonna, C.R.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Lo Feudo, T. Peplospheric Influences on Local Greenhouse Gas and Aerosol Variability at the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW Regional Station in Calabria, Southern Italy: A Multiparameter Investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sector | MTO/LID | LID/MTO |

|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 78.44% | 70.63% |

| West | 76.01% | 74.46% |

| Other | 52.76% | 61.25% |

| Parameter | Sector (WXT520) | Sector (ZephIR) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Northeast | West | All | Northeast | West | |

| NO | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NOx | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Season | Parameter | Sector (WXT520) | Sector (ZephIR) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Northeast | West | All | Northeast | West | ||

|

Winter |

NO | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| NOx | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

|

Spring |

NO | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| NOx | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

|

Summer |

NO | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| NOx | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

|

Fall |

NO | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| NOx | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| Parameter | Wind Sectors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Northeast | West | ||||

| MK | p | MK | p | MK | p | |

| NO | -0.126 | 0.05(7) | -0.102 | 0.12 | -0.202 | < 0.05 |

| NO2 | -0.12 | 0.06 | -0.148 | < 0.05 | -0.117 | 0.07 |

| NOx | -0.131 | < 0.05 | -0.161 | < 0.05 | -0.143 | < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).